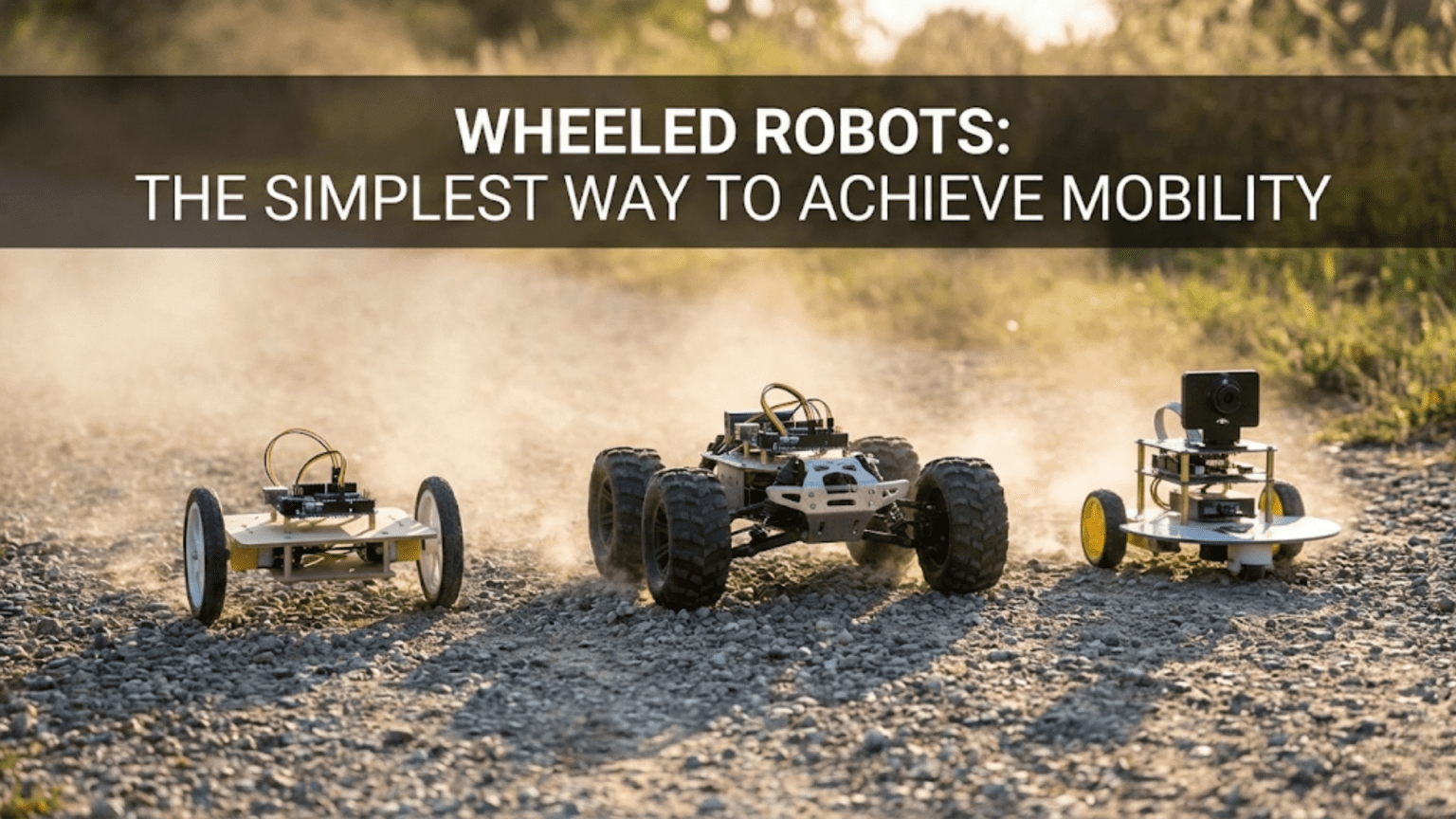

When you think about giving a robot the ability to move, wheels represent the most intuitive and accessible solution. Every day you encounter wheeled vehicles from cars and bicycles to shopping carts and skateboards, making wheel-based motion deeply familiar. This familiarity translates directly into robotics where wheeled robots dominate beginner projects, educational platforms, and even many professional applications. The simplicity of rolling motion compared to walking, flying, or swimming makes wheeled robots the natural starting point for anyone wanting to build their first mobile robot. Understanding why wheels work so well, how different wheel configurations create different capabilities, and what design considerations affect wheeled robot performance helps you create effective mobile robots while building fundamental knowledge that applies across all robotics domains.

Wheels achieve efficient movement through exploiting a fundamental mechanical principle where circular objects rolling on surfaces require far less energy than sliding or dragging the same mass. When a wheel rolls, only a tiny contact patch experiences friction, and that friction primarily acts perpendicular to motion rather than opposing it. This efficiency means small motors can propel substantial robots across smooth surfaces using modest battery capacity. The mechanical simplicity of wheels—essentially just circles rotating around axles—creates reliability and predictability that makes wheeled robots much easier to build and control than more complex locomotion methods. For beginners especially, this combination of efficiency, simplicity, and reliability makes wheeled robots the ideal platform for learning mobile robotics fundamentals.

This article explores wheeled robot design from basic principles through practical implementation guidance. You will learn what makes wheels effective for robot mobility, understand the major wheel types and their characteristics, discover how different wheel configurations create different motion capabilities, and gain practical knowledge for designing your first wheeled robot. Rather than just accepting wheels as the default choice, this deeper understanding reveals both the strengths and limitations of wheeled mobility, preparing you to make informed design decisions and eventually recognize when alternative locomotion methods might serve specific applications better than wheels.

Why Wheels Work So Well for Robots

Before diving into specific wheel types and configurations, understanding the fundamental advantages that make wheels the dominant mobility solution helps you appreciate why wheeled robots remain popular despite alternatives like legs or propellers offering unique capabilities.

Rolling friction proves dramatically lower than sliding friction, creating tremendous efficiency advantages. When an object slides across a surface, friction acts across the entire contact area opposing motion. Overcoming this sliding friction requires substantial force proportional to the object’s weight. When that same object rolls on wheels, friction acts only at tiny contact patches where wheels touch the ground, and most importantly, the friction acts perpendicular to the direction of travel rather than opposing it. This reduction in resistance means wheeled robots require far less motor power to move compared to sliding or dragging robots of equal mass. A wheeled robot might move easily with motors consuming a few watts while achieving the same speed through sliding would require motors consuming tens or hundreds of watts.

Mechanical simplicity of wheels and axles creates straightforward construction that beginners can implement successfully. A wheel mounted on an axle rotates when the axle turns, directly converting motor rotation into forward motion. This simple mechanical arrangement requires no complex linkages, coordinated movements, or precisely timed sequences like legged locomotion demands. You attach wheels to motor shafts or axles, and when motors spin, the robot moves. This directness between motor commands and robot motion simplifies both mechanical construction and software control, letting you focus on higher-level challenges like navigation rather than struggling with fundamental locomotion mechanics.

Predictable kinematics allows calculating where robots will be based on wheel rotations. If you know wheel diameter and you count how many times wheels rotate, you can calculate how far the robot traveled. If you know the spacing between wheels and the relative rotation amounts, you can calculate how much the robot turned. This mathematical predictability enables dead reckoning navigation where robots estimate position by integrating wheel rotations over time. While dead reckoning accumulates errors, having any mathematical model relating motor commands to robot motion provides enormous advantage compared to locomotion methods where predicting exact motion proves difficult due to complex interactions with terrain.

Continuous motion capability means wheeled robots maintain steady movement rather than alternating between stance and swing phases like walking robots. Wheels can spin continuously providing smooth constant-velocity motion ideally suited for transportation and navigation tasks. This continuous motion eliminates the efficiency losses from repeatedly accelerating and decelerating that occur during walking gaits. For applications requiring covering distances efficiently, continuous rolling motion significantly outperforms intermittent locomotion methods.

Speed and efficiency on smooth surfaces make wheels unbeatable for many applications. On flat floors, paved roads, or other prepared surfaces, wheeled vehicles achieve speeds and energy efficiency that no other locomotion method can match. Cars, trains, and bicycles all exploit wheel efficiency for human transportation. The same advantages apply to robots operating in human environments with floors, roads, and pathways designed for wheeled traffic. If your robot operates primarily on smooth prepared surfaces, wheels almost certainly provide the best mobility solution.

Infrastructure compatibility enables wheeled robots to use existing human infrastructure including roads, ramps, elevators, and buildings designed around wheeled vehicle access. Robots can navigate the same spaces and use the same pathways that human-built environments provide for wheeled mobility. This infrastructure leverage means wheeled robots can operate effectively in many real-world environments without requiring environment modification or special provisions.

Basic Wheel Types and Their Characteristics

Not all wheels function identically. Different wheel designs offer different advantages creating options for various robot requirements. Understanding these basic wheel types helps you select appropriate wheels for your robot’s needs.

Standard wheels or fixed wheels mount rigidly to axles, rotating only around the axle axis. These conventional wheels resembling car or bicycle wheels provide the most efficient rolling motion and best traction when rolling in their designated direction. Standard wheels work excellently for forward and backward motion but create difficulty for turning because they resist sideways motion. This directional nature of standard wheels shapes the design of entire robot configurations as you will see when examining different wheel arrangements.

Caster wheels swivel freely around a vertical axis letting them orient to movement direction automatically. Shopping carts use casters on front wheels allowing the cart to turn easily despite having fixed rear wheels. In robots, casters provide freely-rotating support points that do not fight turning motions. Mounting a robot on two driven standard wheels plus one or two caster wheels creates a simple, easily controlled configuration. The casters passively follow wherever the driven wheels take the robot without requiring active steering control. However, casters do introduce some resistance to motion changes and can create unpredictable behavior during rapid direction changes when caster orientation lags behind robot motion.

Omni-directional wheels feature small rollers around the wheel’s circumference perpendicular to the main wheel axis. These rollers let the wheel slide sideways without resistance while still providing traction for forward rolling motion. Omni-wheels enable robots to move in any direction without rotating the chassis first, dramatically increasing maneuverability compared to standard wheels. Three or four omni-wheels arranged appropriately allow holonomic motion where robots can simultaneously rotate and translate in any direction. This additional motion capability comes at costs including reduced traction, increased mechanical complexity, and higher prices compared to standard wheels.

Mecanum wheels represent a specialized omni-wheel variant with rollers angled at forty-five degrees to the wheel axis rather than perpendicular. Four mecanum wheels arranged in a specific configuration enable precise omnidirectional motion including sideways sliding, diagonal movement, and rotation while translating. Mecanum wheels see use in specialized applications requiring exceptional maneuverability in confined spaces. However, they sacrifice efficiency and traction compared to standard wheels, cost significantly more, and require careful mounting and control to function properly. For beginners, mecanum wheels usually represent unnecessary complexity though they provide interesting capabilities once you master basic wheeled robot control.

Ball casters or ball transfers function similarly to furniture casters but use spherical balls rather than wheels. Small robots sometimes use ball casters as passive support points instead of wheel-style casters. Ball casters can rotate in any direction providing minimal resistance to turning. However, they offer less stability than wheel-style casters and work poorly on rough surfaces where balls can catch on irregularities.

Tire materials affect traction, durability, and ride quality. Hard plastic wheels work adequately on smooth floors but provide poor traction on slightly rough surfaces. Rubber tires or foam rubber wheels dramatically improve traction letting robots climb small obstacles and maintain grip on irregular surfaces. Soft wheels also cushion vibrations protecting electronics from mechanical shock. However, soft wheels wear faster than hard wheels and can leave marks on floors. Selecting appropriate tire hardness balances traction needs against durability and surface-marking concerns.

Common Wheeled Robot Configurations

How you arrange wheels on a robot fundamentally determines its mobility characteristics, control complexity, and practical capabilities. Understanding common wheel configurations helps you select appropriate arrangements for your first robots and recognize how configuration affects robot behavior.

Differential drive using two driven wheels and one or two casters represents the most popular configuration for beginner robots. The two driven wheels sit on opposite sides of the robot, each controlled independently by its own motor. When both wheels spin forward at the same speed, the robot drives straight forward. When one wheel spins faster than the other, the robot curves toward the slower wheel. When wheels spin in opposite directions, the robot rotates in place. This simple relationship between individual wheel speeds and robot motion makes differential drive straightforward to program and understand. The caster wheels provide stability without interfering with motion, passively following wherever the driven wheels direct the robot. Nearly all two-wheeled robots including vacuum cleaners, educational robots, and simple mobile platforms use differential drive because it combines simplicity with adequate maneuverability.

The kinematics of differential drive prove elegant and intuitive. The robot’s forward velocity equals the average of the two wheel velocities. The robot’s rotation rate depends on the difference between wheel velocities divided by the wheel spacing. These simple relationships let you calculate exact motor commands producing desired forward speeds and turn rates. Despite this mathematical simplicity, differential drive robots are nonholonomic, meaning they cannot move directly sideways—they must rotate first then drive forward. This constraint rarely matters for navigating open spaces but can complicate maneuvering in tight corridors.

Tricycle or Ackermann steering configurations use front wheel steering like bicycles or cars. One or two front wheels steer left or right while rear wheels drive the robot forward or backward. This configuration feels natural to anyone who has ridden bicycles or driven cars. However, Ackermann steering requires more complex mechanics including steering linkages and steering servos beyond the motor controllers needed for differential drive. The control relationship between steering angle and turning radius follows more complex mathematics than differential drive’s simple wheel-speed relationship. For these reasons, Ackermann steering sees less use in beginner robotics despite its familiarity from vehicles. Small robots sometimes use simplified tricycle configurations with a steerable front caster and two driven rear wheels.

Four-wheel drive platforms with independent control of all four wheels provide maximum traction and obstacle climbing ability. Construction vehicles and off-road robots often use four-wheel drive to maintain traction on rough terrain. However, coordinating four independent motors adds control complexity and cost compared to two-wheel drive. Most four-wheel platforms simplify control by mechanically linking wheel pairs so the left and right sides each have one motor despite having two wheels. This reduces control complexity while maintaining the traction benefits of four contact points.

Six-wheel or multi-wheel configurations spread robot weight across more contact points improving weight distribution and obstacle crossing. Planetary rovers often use six-wheel designs where the suspension allows wheels to conform to irregular terrain while maintaining all wheels in contact with the ground. For flat-surface robots, six wheels provide little advantage over four wheels while adding weight and complexity. However, for outdoor robots or those traversing obstacles, additional wheels improve performance significantly.

Tank treads or continuous tracks distribute weight over long contact areas rather than discrete wheel points. Tracked robots handle loose surfaces, climb stairs, and cross obstacles better than equivalent wheeled robots. However, tracks require more complex mechanics, cost more than wheels, and suffer higher friction losses reducing efficiency. Except for specialized applications requiring maximum traction or obstacle crossing, wheels prove simpler and more efficient than tracks.

Omnidirectional platforms using three or four omni-wheels arranged to enable holonomic motion represent the most maneuverable wheeled configuration. These robots can instantly move in any direction and rotate simultaneously without first reorienting. This capability proves valuable in constrained spaces or when precise positioning matters more than efficiency. However, omnidirectional platforms cost more, provide less traction, and require more sophisticated control than differential drive robots. Beginning roboticists should master differential drive before attempting omnidirectional platforms.

Designing Your First Wheeled Robot

With understanding of wheel types and configurations, you can now design your first wheeled robot making informed decisions about components and layout. This practical guidance helps you avoid common beginner mistakes while building working mobile robots.

Start with differential drive configuration for your first robot. This time-tested arrangement combines simplicity, adequate performance, and straightforward control. Plan for two driven wheels on opposite sides of your robot and one or two caster wheels for stability. This configuration lets you focus on learning fundamental concepts like motor control and navigation without struggling with complex mechanics or control algorithms. After successfully building differential drive robots, you can explore more exotic configurations if your applications demand their special capabilities.

Select wheel diameter considering your desired speed and terrain. Larger wheels roll over obstacles more easily and achieve higher speeds for given motor rotation rates. Smaller wheels fit in compact robots and provide finer control at low speeds. For flat indoor surfaces, wheels from fifty to one hundred millimeters in diameter work well for robots weighing a few kilograms. Outdoor robots or those navigating rougher surfaces benefit from larger wheels of one hundred to two hundred millimeters. Avoid tiny wheels under thirty millimeters for mobile robots as they catch on every small imperfection in flooring.

Choose wheels with rubber or foam rubber tires rather than hard plastic for most applications. The improved traction from slightly soft tires dramatically helps performance. Robots with hard plastic wheels slip when accelerating, have difficulty climbing even gentle ramps, and provide poor odometry accuracy due to wheel slip. Spending a bit more for rubber-tired wheels prevents frustrating performance limitations. Only choose hard plastic wheels if you absolutely need the lowest possible cost and operate exclusively on very smooth surfaces.

Position drive wheels slightly forward of center of mass for stability. If drive wheels sit directly at the center of mass, the robot can tip backward or forward easily. Placing drive wheels forward biases weight distribution so the robot naturally pitches forward onto the casters providing stable operation. Exactly how far forward depends on robot proportions, but aim for drive wheels at roughly one-third of the total length from the front of the robot.

Space drive wheels as widely apart as your chassis allows. Wider wheel spacing provides better stability preventing tipping and enables sharper turns for given motor speed differences. The turning radius for a differential drive robot depends on the wheelbase—wider spacing creates smaller minimum turn radii. However, very wide wheelbase creates a large rotational footprint making the robot difficult to maneuver in tight spaces. Balance these competing considerations aiming for wheelbase approximately sixty to eighty percent of the robot’s length dimension.

Select motors with adequate torque to drive your robot at desired speeds. Calculate required torque by estimating robot weight, desired acceleration, and any inclines or obstacles the robot must overcome. Don’t forget to account for gearing between motors and wheels. Undersized motors cause frustrating poor performance where robots cannot accelerate briskly or climb even gentle slopes. Oversized motors waste money and battery capacity. For a first robot weighing two to three kilograms on flat floors, small geared DC motors providing five to ten kilogram-centimeters of torque at the wheel prove adequate.

Mount motors securely to the chassis with provisions for precise wheel alignment. Misaligned wheels cause robots to veer to one side even when motors receive identical commands. Careful motor mounting ensuring both drive wheels remain parallel and perpendicular to the chassis direction creates straight motion at matched motor speeds. Some beginning robots use motor mount brackets allowing slight adjustment to correct minor alignment errors discovered during testing.

Position caster wheels to provide stable support without creating control difficulties. Front casters should sit far enough forward to prevent forward tipping but not so far that they create excessive moment arm resisting turns. Many differential drive robots use two small casters in front providing stable four-point support. Single rear casters work adequately for lightweight robots but can allow rear tipping if positioned poorly. Test different caster positions if initial placement creates unstable or poor turning behavior.

Consider adding wheel encoders for dead reckoning navigation. Encoders provide feedback about wheel rotations enabling the robot to estimate how far it has traveled and how much it has turned. This odometry information dramatically improves navigation accuracy compared to purely open-loop control relying on timing. Many educational robots include encoders by default. If building from scratch, plan for encoder mounting from the start rather than trying to retrofit them later.

Wheel Selection Practical Considerations

Beyond basic wheel type and size selection, various practical factors affect wheel choice and robot performance. Understanding these considerations helps you avoid common problems and achieve good results with your first wheeled robot.

Mounting compatibility between wheels and motors determines whether wheels actually fit your selected motors. Wheels typically mount via press-fit onto motor shafts, attach with set screws to D-shaped shafts, or connect through shaft couplers to round shafts. Verify that wheels you choose have mounting holes or attachments compatible with your motor shaft dimensions. Buying wheels and motors from the same manufacturer or verified compatible sources prevents frustrating discovery that wheels and motors do not physically connect.

Wheel material compatibility with your environment prevents damage to floors or wheels. Soft rubber wheels can leave black marks on light-colored floors. Very soft wheels might damage certain floor finishes. If operating indoors where floor protection matters, choose non-marking rubber compounds specified for indoor use. Conversely, outdoor robots benefit from harder rubber compounds that resist weathering and wear from abrasive surfaces.

Load capacity specifications indicate maximum weight wheels can safely support. Each wheel has design limits for how much weight it can carry without deforming or failing. Distribute robot weight across all wheels and verify that the load on each wheel remains within its rated capacity. Exceeding load ratings causes wheels to deform affecting robot motion accuracy or potentially failing catastrophically during operation.

Bearing quality affects wheel efficiency and longevity. Wheels with good ball bearings or sealed bearings roll smoothly with minimal friction and remain reliable for thousands of hours. Cheap wheels with poor bearings or simple bushings instead of real bearings create higher friction and wear quickly. For robots that will see extensive use, spending more for wheels with quality bearings proves worthwhile. For occasional-use learning projects, basic wheels suffice accepting higher friction and shorter lifetime.

Hub attachment security prevents wheels from working loose during operation. Set screw wheel attachments must be tightened adequately and checked periodically. Press-fit wheels may need adhesive or cross-pins to prevent wheels from walking off shafts during direction reversals or high-torque situations. Wheels coming loose during operation create confusing robot behavior and potential component damage. Secure all wheel attachments properly and verify they remain tight during testing.

Spare wheel availability matters for robots that will see heavy use or operate in environments causing wear. If you choose unusual wheel types or specialty wheels from single suppliers, consider purchasing spares when initially buying wheels. Nothing proves more frustrating than having a robot sidelined waiting for replacement wheels when the exact wheel model is backordered or discontinued.

Common Wheeled Robot Problems and Solutions

Even well-designed wheeled robots encounter predictable problems during development and operation. Recognizing these common issues and their solutions helps you troubleshoot effectively when your robot misbehaves.

Veering to one side despite identical motor commands usually indicates motor differences or wheel misalignment. Motors from the same manufacturer still vary slightly in their speed-torque characteristics. One motor might spin slightly faster than the other at the same voltage. Wheels mounted slightly off-parallel amplify these differences causing noticeable veering. Solve this by measuring actual wheel speeds and adjusting PWM duty cycles to achieve equal speeds rather than assuming equal voltages produce equal speeds. Software calibration that stores correction factors for each motor compensates for hardware variations creating straight motion.

Poor traction causing wheel slip during acceleration indicates hard wheels or excessive acceleration rates for available traction. Softer rubber wheels dramatically improve traction. Reducing maximum acceleration rates lets available traction act over longer time producing the same final velocity without exceeding traction limits. Adding weight over drive wheels increases normal force and therefore available friction improving traction. However, avoid excessive weight that strains motors or reduces battery life.

Difficulty turning or sluggish turn response often results from caster wheel resistance or stuck casters. Casters must swivel freely to allow turning. Casters with poor bearings, debris in swivel mechanisms, or inadequate clearance scraping the floor create resistance that fights turning motions. Verify casters rotate smoothly by hand. Lubricate caster swivels if stiff. Adjust caster height to minimize floor scraping while maintaining robot stability.

Unstable or rocking motion might indicate uneven weight distribution or caster placement problems. Robots that rock back and forth as they drive have their center of mass poorly positioned relative to drive wheels and casters. Redistributing weight or repositioning casters eliminates this instability. Robots with very short wheelbase or those carrying tall loads sometimes remain inherently unstable requiring wider wheel spacing or lower center of mass.

Excessive battery drain suggests inefficient wheel selection, binding in drive trains, or poor surface compatibility. Verify that wheels rotate freely when motors are off—significant coasting resistance indicates bearing problems or drive train binding requiring mechanical fixes. Very soft wheels create higher rolling resistance than moderately firm wheels. Operating on soft surfaces like deep carpet creates rolling resistance far exceeding hard floor operation—either accept reduced runtime or choose different operating environments.

Unexpected obstacle failures where robots cannot climb obstacles they theoretically should handle often trace to approach angle limitations. Wheel robots require approaching obstacles nearly perpendicular—if approaching at an angle, wheels catch and slide rather than climbing. Obstacle height limits depend on wheel diameter with larger wheels clearing higher obstacles. Obstacles exceeding roughly one-third of wheel diameter become difficult or impossible to surmount for simple wheeled robots.

When Wheels Are Not the Right Answer

Despite their many advantages, wheels have fundamental limitations that make them unsuitable for certain applications. Recognizing these limitations helps you identify when alternative locomotion methods serve better than wheels.

Rough or irregular terrain defeats wheeled robots because wheels require relatively smooth continuous surfaces to roll efficiently. Natural outdoor terrain with rocks, vegetation, soft soil, or steep slopes proves difficult or impossible for wheeled robots to traverse. While tracked robots handle rough terrain better than wheels, truly challenging natural environments require legged locomotion that can step over obstacles and adapt to irregular surfaces. If your robot must operate in forests, mountains, or other natural terrain, wheels provide poor mobility despite their advantages on prepared surfaces.

Stairs and steps remain difficult for wheeled robots despite various clever mechanisms attempting to solve this problem. Standard wheels cannot climb conventional stairs. Tracked robots climb stairs better but still struggle with steep or irregular steps. Most wheeled robots simply avoid stairs, limiting their useful range in multi-story buildings. If your application requires navigating stairs regularly, legged robots or specialized climbing mechanisms prove necessary.

Very small size constraints favor alternative locomotion because wheels require minimum space for practical designs. Below certain robot sizes, wheels become impractically small providing poor obstacle clearance and fragile mechanical construction. Tiny robots might use vibration-based motion or other non-wheeled approaches more effectively than attempting to build functional wheels at miniature scale.

Omnidirectional precise positioning requirements in constrained spaces sometimes exceed wheeled robot capabilities. While omnidirectional wheels enable holonomic motion, they sacrifice traction and add complexity. Applications requiring extremely precise positioning with high forces in multiple directions—such as certain industrial assembly tasks—might use wheeled mobile bases for coarse positioning combined with other mechanisms for precision, or might abandon wheels entirely for alternative approaches like cable-driven systems or parallel robots.

Aquatic, aerial, or climbing applications clearly require alternatives to wheels. Water requires propellers or fins for propulsion. Air demands propellers or wings. Climbing vertical surfaces needs grippers, suction, or magnetic adhesion. Wheels fundamentally require ground contact and gravity to function. While some creative designs combine wheeled motion on surfaces with other locomotion modes for non-surface travel, pure wheeled robots cannot operate in these domains.

Conclusion: Wheels as Your Robotics Foundation

Wheeled robots represent the ideal starting point for learning mobile robotics because they combine mechanical simplicity, control predictability, and practical performance in an accessible package. The differential drive configuration particularly deserves your attention as a first robot platform, providing enough capability to learn fundamental concepts while remaining simple enough that beginners can build and program successfully. Success with basic wheeled robots builds confidence and provides foundation for understanding more complex mobility solutions.

Your first wheeled robot will teach lessons extending far beyond wheels themselves. You will learn about motor control, sensor integration, power management, and navigation challenges that apply across all mobile robots. These fundamental concepts transfer to legged robots, flying drones, and other platforms even though the specific kinematics differ. Wheels provide accessible entry point to these universal concepts without overwhelming complexity that might discourage continued learning.

As you progress beyond initial wheeled robots, you will encounter scenarios where wheels prove limiting and alternative locomotion methods offer advantages. Recognizing these limitations comes from experience with wheels, understanding what they do well and where they struggle. This experience-based knowledge helps you make informed decisions about when to persist with wheels and when to explore alternatives rather than fighting unsuitable terrain or applications with inadequate tools.

The robotics community offers extensive resources for wheeled robot development because so many people start their robotics journeys with wheels. Tutorials, code libraries, mechanical designs, and troubleshooting guides abound specifically for wheeled platforms. This wealth of shared knowledge accelerates your learning and helps when you encounter obstacles. Contributing your own experiences and projects back to this community helps others while deepening your own understanding through teaching and documentation.

Start your mobile robotics exploration with a simple differential drive robot using two motors, wheels with rubber tires, and one or two casters. Build it carefully with attention to wheel alignment and motor mounting. Program basic forward, backward, and turning motions. Experiment with different speeds and turning radii. Add sensors and implement obstacle avoidance or line following. This hands-on experience with fundamental wheeled robotics provides foundation supporting everything you will build throughout your robotics journey, making wheels truly the simplest yet most valuable way to achieve your first robot mobility.