Understanding Architecture, Memory, and Performance

When you download software or purchase a computer, you’ve likely encountered the terms “32-bit” and “64-bit” alongside system requirements and processor descriptions. These numbers appear in operating system versions, processor specifications, and application compatibility notes. While they might seem like arbitrary technical designations, the difference between 32-bit and 64-bit architectures fundamentally affects how your computer processes information, how much memory it can use, and what software it can run. Understanding this distinction reveals important aspects of computer architecture and helps you make informed decisions about hardware and software choices.

The terms 32-bit and 64-bit refer to the way a computer’s processor handles information at the most fundamental level. Specifically, they describe the width of the processor’s registers—the tiny, ultra-fast storage locations built directly into the processor where it performs calculations and stores data it’s actively working with. A 32-bit processor uses registers that can hold 32 binary digits (bits) at once, while a 64-bit processor uses registers that hold 64 bits. This seemingly simple difference cascades through the entire computing system, affecting memory addressing, data processing speed, and the overall capabilities of the machine.

The transition from 32-bit to 64-bit computing represents one of the most significant architectural shifts in personal computing history, comparable to earlier transitions from 8-bit to 16-bit and 16-bit to 32-bit systems. This evolution wasn’t merely about incrementally better performance—it fundamentally expanded what computers could do, particularly regarding memory capacity. Today, 64-bit systems have become the standard for desktop and laptop computers, while 32-bit systems persist primarily in older machines, embedded devices, and some specialized applications. Understanding why this transition happened and what it means for everyday computing provides valuable insight into computer architecture and operating system design.

Memory Addressing: The Most Visible Difference

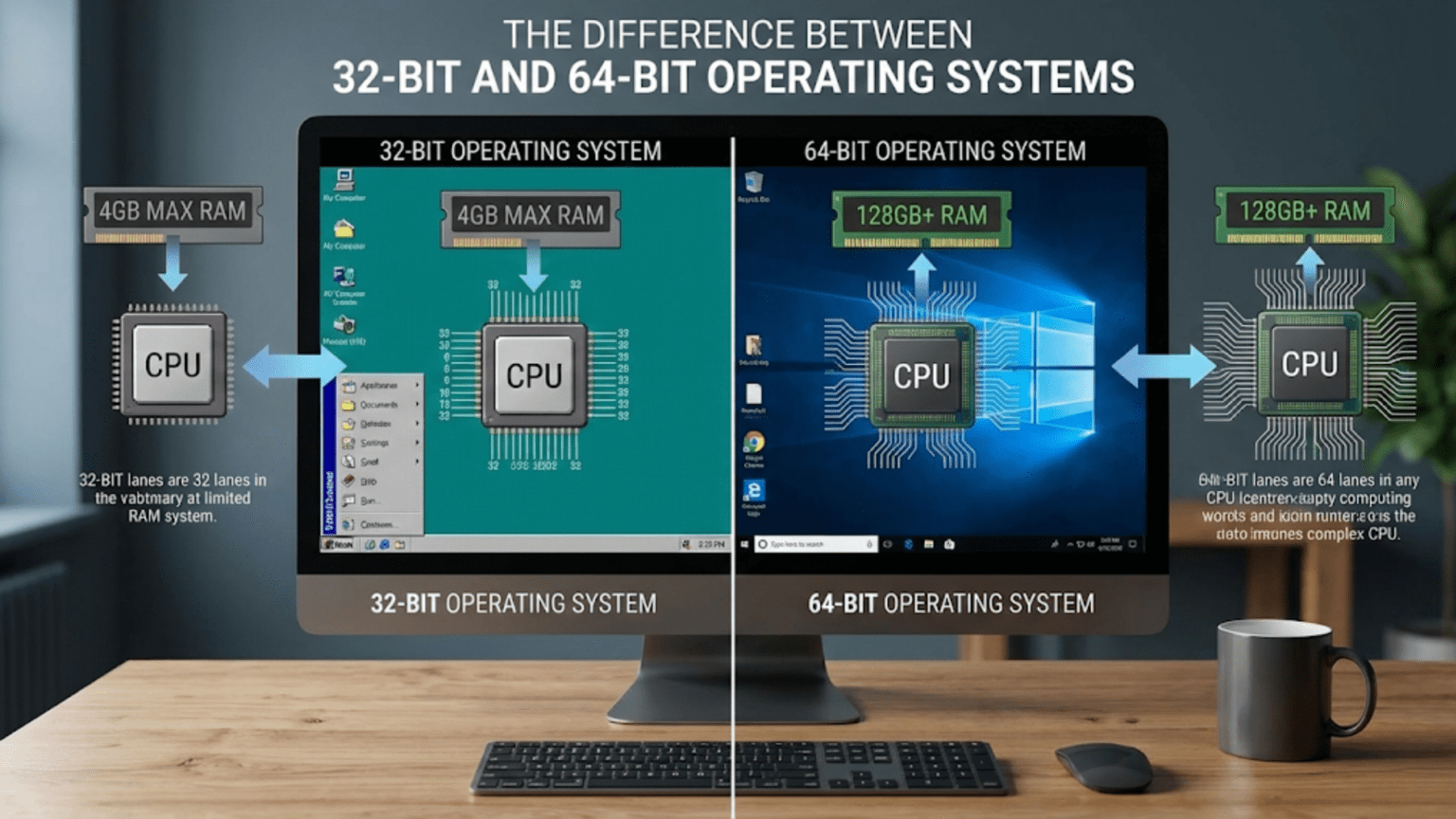

The most immediate and practical difference between 32-bit and 64-bit systems involves memory addressing—how the system identifies and accesses locations in RAM. Every byte of memory in your computer has an address, like a house on a street. The processor uses these addresses to read data from and write data to specific memory locations. The number of bits available for addressing directly determines the maximum amount of memory the system can theoretically access.

A 32-bit system uses 32-bit addresses, allowing it to represent 2^32 different memory locations. This equals exactly 4,294,967,296 addresses or 4 gigabytes of addressable memory. This might sound like a generous amount, but it includes all memory in the system—not just RAM but also memory used by graphics cards, memory-mapped hardware devices, and system firmware. In practice, 32-bit Windows typically recognizes only about 3.5 gigabytes of RAM even if you install more, because the remaining address space is reserved for hardware. This limitation became increasingly problematic as applications grew more memory-hungry and RAM prices fell, making 8, 16, or 32 gigabytes of RAM common and affordable.

A 64-bit system uses 64-bit addresses, theoretically supporting 2^64 different memory locations—approximately 18.4 million terabytes or 18.4 exabytes. This number is so astronomically large that it won’t present practical limitations for decades, probably generations. Current 64-bit processors don’t actually implement all 64 address bits—most use 48-bit addressing, supporting 256 terabytes of RAM, which still far exceeds any current practical need. Operating systems impose their own limits below the hardware maximum: 64-bit Windows Home editions support up to 128 gigabytes, Professional editions up to 2 terabytes, and server editions even more.

This expanded memory capacity enables applications that were impossible on 32-bit systems. Video editing software working with 4K or 8K footage can keep entire projects in RAM for smooth editing. Virtual machines can allocate realistic amounts of memory to guest operating systems. Scientific simulations can model systems with billions of elements. Database servers can cache enormous datasets in memory for lightning-fast queries. Large-scale data analysis becomes practical. While most everyday applications don’t need more than 4 gigabytes, the ability to exceed that limit when needed represents a fundamental expansion of computing capability.

The memory limit affects not just how much RAM the system can use but also how large individual applications can be. On 32-bit systems, a single application can address only 2 or 3 gigabytes of memory (depending on operating system configuration), even if the system has more RAM installed. This limit constrains large applications regardless of total system memory. On 64-bit systems, individual applications can use terabytes of memory if needed, though most don’t require anywhere near that much. This distinction matters for memory-intensive applications like professional video editing, 3D rendering, scientific computing, or running multiple virtual machines.

Processing Power and Performance Advantages

Beyond memory addressing, 64-bit architectures provide performance advantages that make applications run faster, particularly for certain types of workloads. These performance benefits stem from several architectural improvements that accompany the transition to wider registers.

The wider 64-bit registers allow processors to work with larger chunks of data in a single operation. When processing data types larger than 32 bits—which includes many modern data structures, pointers on 64-bit systems, and certain numeric calculations—a 64-bit processor can handle them more efficiently. A 64-bit processor can process a 64-bit integer in one operation, while a 32-bit processor might require multiple operations to handle the same calculation. For applications that work extensively with large numbers, scientific calculations, cryptography, or data compression, this native 64-bit processing provides measurable performance improvements.

Modern 64-bit processors include additional general-purpose registers beyond what 32-bit processors provide. The x86 architecture (32-bit) provides eight general-purpose registers, while x86-64 (64-bit) provides sixteen. These additional registers give compilers more flexibility when optimizing code, allowing them to keep more values in ultra-fast register storage rather than slower memory. This improvement doesn’t require any changes to existing code—simply recompiling a program for 64-bit can yield performance benefits because the compiler automatically takes advantage of the additional registers.

The 64-bit instruction sets also include improvements and extensions beyond just wider data handling. Modern processors implement various instruction set extensions—SSE, AVX, and others—that provide specialized operations for common tasks like multimedia processing, encryption, or vector mathematics. While some of these extensions are technically available on late-model 32-bit processors, 64-bit systems guarantee their availability, allowing software developers to use them without worrying about compatibility. Applications can perform complex operations more efficiently, processing multiple data elements simultaneously through these vectorized instructions.

However, it’s crucial to understand that 64-bit systems aren’t universally faster for all workloads. Applications that don’t need more than 4 gigabytes of memory or don’t perform operations that benefit from 64-bit processing may show minimal performance differences between 32-bit and 64-bit versions. In some cases, 64-bit programs can actually be slightly larger and use more memory than their 32-bit equivalents because pointers and certain data structures double in size. For many typical desktop applications—web browsing, word processing, email—the performance difference is negligible. The benefits become apparent with specific workloads: video encoding, 3D rendering, scientific calculations, database operations, virtual machines, or any memory-intensive application.

Software Compatibility and Installation Considerations

The transition to 64-bit computing raises important compatibility questions. Can 64-bit systems run 32-bit software? Can 32-bit systems run 64-bit software? What about drivers and system-level components? Understanding these compatibility relationships helps explain certain installation requirements and troubleshooting scenarios.

A 64-bit operating system can run most 32-bit applications through a compatibility layer. Windows implements this through WoW64 (Windows 32-bit on Windows 64-bit), a subsystem that translates 32-bit system calls to their 64-bit equivalents. When you launch a 32-bit application on 64-bit Windows, WoW64 intercepts the application’s system calls, converts them to the appropriate 64-bit versions, and presents the results back to the application in the format it expects. This translation happens transparently—the 32-bit application doesn’t know it’s running on a 64-bit system. Linux systems provide similar compatibility through 32-bit libraries that can be installed alongside 64-bit system libraries.

This compatibility isn’t perfect or complete. Some 32-bit software, particularly older programs or those using certain low-level features, may encounter issues on 64-bit systems. 16-bit applications from the DOS and early Windows era cannot run on 64-bit Windows at all because WoW64 doesn’t support 16-bit translation. Certain kernel-mode drivers and system-level software must match the operating system’s architecture—you cannot load a 32-bit device driver into a 64-bit kernel. This driver requirement was a significant challenge during the early 64-bit transition, as hardware manufacturers needed to develop new 64-bit drivers for their devices.

The reverse compatibility doesn’t exist at all. A 32-bit operating system cannot run 64-bit applications under any circumstances. The 32-bit operating system doesn’t understand 64-bit instructions, doesn’t know how to handle 64-bit system calls, and can’t provide the memory addressing that 64-bit applications expect. This one-way compatibility means that if you’re running a 32-bit operating system, you must use 32-bit versions of applications—64-bit versions simply won’t work. Many modern applications are distributed only in 64-bit versions, effectively requiring a 64-bit operating system.

Operating system installation requires a 64-bit processor to install a 64-bit OS. You cannot install a 64-bit operating system on a 32-bit processor—the processor must support 64-bit instruction sets. Most processors manufactured in the last fifteen years support 64-bit operation, but very old computers may have 32-bit-only processors that cannot run modern 64-bit operating systems. Checking your processor specifications before attempting to upgrade to a 64-bit OS prevents frustrating installation failures.

When choosing between 32-bit and 64-bit software versions, the decision depends on your operating system and needs. On a 64-bit operating system with more than 4 gigabytes of RAM, choosing 64-bit applications allows them to use all available memory and potentially run faster. On systems with 4 gigabytes or less, the difference is less significant, though 64-bit applications may still perform better for certain tasks. On 32-bit operating systems, you have no choice—32-bit applications are your only option.

The Technical Architecture: How Bits Affect Everything

Understanding what happens inside the processor helps clarify why the number of bits matters so fundamentally. At the lowest level, computers operate on binary digits—bits that can be either 0 or 1. Everything the processor does involves manipulating these bits through logic operations. The processor’s architecture determines how many bits it can work with simultaneously, and this affects everything from the instructions it can execute to the amount of memory it can address.

Inside the processor, registers store data during calculations. When a program performs arithmetic—adding two numbers, for example—the processor loads those numbers into registers, performs the addition using its arithmetic logic unit, and stores the result back in a register. On a 32-bit processor, each register holds 32 bits, limiting native arithmetic to 32-bit integers (roughly -2 billion to +2 billion). Calculations involving larger numbers require multiple operations, breaking the larger number into 32-bit chunks and processing them separately, then combining the results—slower and more complex than handling it in one operation.

A 64-bit processor’s registers hold 64 bits, allowing native operations on 64-bit integers (roughly -9 quintillion to +9 quintillion). This isn’t just about handling bigger numbers—it’s about efficiency. Modern programming frequently uses 64-bit values: timestamps measured in milliseconds or nanoseconds, file sizes and positions in large files, memory addresses on 64-bit systems, and various data structures. When the processor can handle these values natively, operations complete faster and code becomes simpler.

Instruction sets define what operations the processor can perform. The transition from 32-bit to 64-bit included expanding instruction sets with new capabilities. The x86-64 architecture (also called AMD64 or x64) extends the original x86 instruction set with 64-bit operations while maintaining backward compatibility with 32-bit code. This extension includes not just wider data operations but also additional instructions for specialized tasks, more registers for improved performance, and architectural improvements that benefit all code regardless of whether it uses 64-bit operations.

Memory addressing uses registers to hold addresses—locations in memory where data resides. On 32-bit systems, addresses are 32-bit values, limiting addressable memory to 2^32 bytes (4 gigabytes). On 64-bit systems, addresses are 64-bit values, theoretically allowing 2^64 bytes (18.4 million terabytes). The operating system uses these address registers when managing virtual memory, translating virtual addresses that programs use to physical addresses in RAM. Wider address registers directly enable larger memory capacity—there’s no way around this fundamental mathematical constraint.

The processor’s data bus—the connections between the processor and memory—also reflects the architecture. A 64-bit processor typically has a 64-bit data bus, allowing it to transfer 64 bits (8 bytes) per memory operation. A 32-bit processor’s 32-bit data bus transfers only 32 bits (4 bytes) per operation. This affects memory bandwidth—how quickly data can move between processor and memory. For applications that process large amounts of data, this bandwidth difference contributes to performance advantages on 64-bit systems.

Operating System Implementations and Practical Differences

Different operating systems implement 32-bit and 64-bit support in different ways, with various implications for users. Understanding these implementations helps explain why certain limitations exist and how operating systems handle the transition between architectures.

Windows clearly separates 32-bit and 64-bit versions. When you install Windows, you must choose between 32-bit and 64-bit editions (if your processor supports 64-bit). The two versions cannot coexist—you run either 32-bit Windows or 64-bit Windows, not both. Windows stores 32-bit applications in “Program Files (x86)” and 64-bit applications in “Program Files,” keeping them separate for clarity. The system maintains both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of system libraries, automatically selecting the appropriate version based on the application being run.

Modern Windows versions have largely abandoned 32-bit support. Windows 10 was the last version to offer 32-bit installations, and even those were limited to specific scenarios. Windows 11 is exclusively 64-bit, requiring a 64-bit processor and declining to install on 32-bit systems. This reflects the reality that 32-bit systems have become obsolete for general computing—essentially all modern processors support 64-bit operation, and the memory limitations of 32-bit systems are unacceptable for contemporary applications.

Linux distributions handle architecture support flexibly. Most distributions offer both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of their installation media, though many have dropped 32-bit support in recent years as the need diminishes. Linux can install both 32-bit and 64-bit libraries simultaneously, allowing 32-bit applications to run on 64-bit systems with explicit 32-bit library support. Some distributions continue supporting 32-bit installations for older hardware, embedded systems, or specialized applications, though mainstream support has largely moved to 64-bit exclusively.

macOS transitioned to 64-bit relatively early and aggressively. macOS Catalina (2019) dropped support for 32-bit applications entirely—attempting to run a 32-bit application produces an error message explaining that the application needs to be updated. This forced transition pushed developers to update their software or abandon the macOS platform, ensuring that the macOS ecosystem fully embraced 64-bit computing. Apple’s subsequent transition to their own Apple Silicon processors (which are 64-bit-only) continued this commitment to modern architecture.

Mobile operating systems were designed as 64-bit from relatively early in their evolution. iOS added 64-bit support with the iPhone 5s in 2013 and dropped 32-bit application support entirely in iOS 11 (2017). Android added 64-bit support in 2014 and has progressively pushed toward 64-bit-only. Google Play Store now requires all applications to provide 64-bit versions, though 32-bit versions can coexist for compatibility. This mobile-first approach to 64-bit adoption reflects that mobile devices had less legacy software to support and could make transitions more cleanly than desktop systems.

Security Implications of 64-bit Architecture

The transition to 64-bit computing brought security benefits beyond just increased memory capacity. Modern 64-bit operating systems implement security features that are difficult or impossible on 32-bit systems, making 64-bit systems inherently more secure against certain types of attacks.

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) works more effectively on 64-bit systems due to the vastly larger address space. ASLR randomizes where programs and system libraries load in memory, making it harder for attackers to predict memory locations for exploitation. On 32-bit systems, the limited address space constrains how much randomization is possible—with only 4 gigabytes of address space, attackers can sometimes guess or brute-force addresses successfully. On 64-bit systems, the enormous address space provides so much entropy for randomization that guessing becomes computationally infeasible, significantly strengthening this security mechanism.

Kernel-mode code signing became mandatory on 64-bit Windows, requiring all kernel-mode drivers to be digitally signed by Microsoft or a trusted certificate authority. This prevents malicious kernel-mode rootkits from loading, as unsigned code cannot run at the kernel level. While this restriction technically could be implemented on 32-bit systems, Microsoft enforced it specifically on 64-bit Windows as part of their security strategy. This requirement forced hardware vendors to properly sign their drivers and prevented many rootkit installation methods.

Data Execution Prevention (DEP) or No-Execute (NX) capabilities, while technically available on some late-model 32-bit processors, became standard and always-enabled on 64-bit systems. DEP marks memory regions as either executable (containing program code) or non-executable (containing only data). Attempts to execute code from non-executable memory regions fail, preventing a common attack technique where malicious code is injected into data buffers and then executed. On 64-bit systems, this protection is always active and comprehensive.

The additional registers in 64-bit architecture provide compilers with more opportunities to implement security mitigations without severe performance penalties. Security features like stack canaries, which detect buffer overflow attacks, work more efficiently when registers are plentiful. Certain exploit mitigation techniques that would be too expensive on 32-bit systems become practical on 64-bit systems because the additional registers reduce the performance cost.

However, 64-bit systems aren’t immune to security vulnerabilities. While certain attack vectors become more difficult, others remain effective. Vulnerabilities in application logic, poor encryption implementation, social engineering attacks, and many other security issues aren’t affected by the processor architecture. The transition to 64-bit provides important security improvements but doesn’t eliminate the need for comprehensive security practices, regular updates, and careful system administration.

Making the Choice: When 32-bit Still Matters

Despite 64-bit computing becoming the standard, scenarios exist where 32-bit systems remain relevant or even preferable. Understanding these scenarios helps explain why 32-bit options haven’t completely disappeared despite clear technical advantages for 64-bit.

Older hardware that predates 64-bit processors must use 32-bit operating systems. Computers from the early 2000s or before have processors that don’t support 64-bit operation. These systems can run modern 32-bit Linux distributions or older 32-bit Windows versions, extending their useful life. While performance is limited compared to modern systems, they can still serve specific purposes like dedicated music players, retro gaming systems, or simple web browsing terminals.

Embedded systems and specialized industrial equipment often use 32-bit processors because they’re sufficient for the task, cheaper than 64-bit alternatives, and consume less power. A microwave oven, thermostat, or industrial controller doesn’t need to address more than 4 gigabytes of memory. Using a 32-bit processor reduces costs and power consumption while providing adequate performance. Many embedded operating systems continue supporting 32-bit architectures for these applications.

Some legacy software applications exist only in 32-bit versions and cannot be replaced or updated. Businesses sometimes depend on custom software developed years ago where the original developers are no longer available to create 64-bit versions. Rather than costly redevelopment, these organizations maintain 32-bit systems or use 32-bit compatibility modes to keep critical applications running. While not ideal, this pragmatic approach allows essential business functions to continue while gradually planning migrations.

Virtual machines sometimes run 32-bit operating systems to reduce memory overhead. A 64-bit operating system requires more memory than a 32-bit version for the same functionality because pointers and certain data structures are larger. When running multiple virtual machines on a server with limited RAM, using 32-bit guest operating systems can allow more VMs to coexist. This optimization trades the benefits of 64-bit computing for higher VM density.

The ongoing decline in 32-bit support reflects the reality that its limitations outweigh its benefits for mainstream computing. Memory requirements for modern applications have grown beyond the 4-gigabyte limit. Security improvements in 64-bit systems are significant. Performance benefits, while sometimes modest, favor 64-bit. Unless you have specific reasons to use 32-bit systems—truly ancient hardware, special compatibility needs, or embedded applications—64-bit represents the clear choice for new installations and hardware purchases.

The Future: Beyond 64-bit

While 64-bit computing has become standard and will remain so for decades, computer architects continue exploring what might come next. The theoretical limit of 64-bit addressing—18.4 million terabytes—won’t be a practical constraint for generations, but other aspects of computer architecture continue evolving.

Some researchers explore 128-bit computing, though not necessarily for the same reasons that drove previous transitions. The primary motivation isn’t memory addressing—64-bit addresses are sufficient—but rather cryptography, scientific computing, and specialized calculations that benefit from working with very large numbers natively. Cryptographic algorithms using 128-bit or larger keys, scientific simulations requiring extreme precision, or financial calculations involving very large values might benefit from native 128-bit operations.

However, a wholesale transition to 128-bit computing seems unlikely in the foreseeable future. The memory addressing advantages that justified previous transitions don’t apply—we don’t need to address more than 18.4 million terabytes. The complexity and cost of such a transition would be enormous. More likely, we’ll see specific 128-bit instructions added to 64-bit processors for specialized tasks, similar to how current processors include specialized instruction sets for encryption, multimedia, or vector mathematics alongside their general-purpose 64-bit operations.

Alternative computing paradigms might evolve beyond traditional bit-width classifications. Quantum computers work on fundamentally different principles. Neuromorphic chips mimic biological neural networks. These technologies don’t fit into the 32-bit/64-bit/128-bit progression because they operate on entirely different architectural principles. While these remain specialized or experimental technologies, they represent possible futures where the question of register width becomes less relevant or is replaced by completely different considerations.

For practical purposes, 64-bit computing represents the foreseeable future of mainstream computing. Understanding the differences between 32-bit and 64-bit systems provides insight into computer architecture, explains various limitations and capabilities, and helps make informed decisions about hardware and software. This knowledge connects to broader understanding of how computers work at fundamental levels, from the individual bits in processor registers to the vast addressing spaces that enable modern applications and the security features that protect our systems from increasingly sophisticated threats.