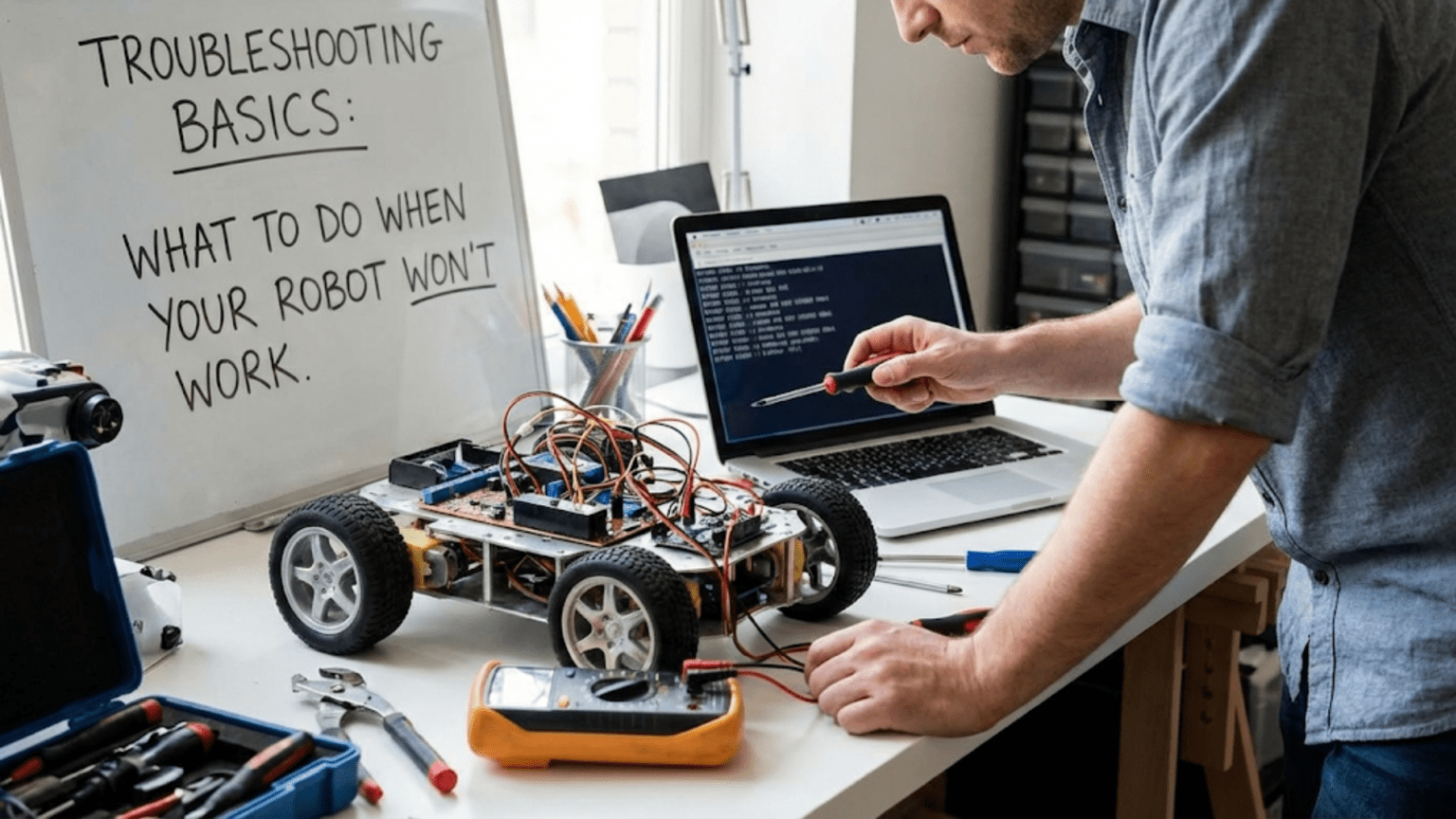

Robot troubleshooting is the systematic process of identifying and resolving problems that prevent your robot from functioning correctly. It involves using logical diagnostic methods to isolate issues, testing hypotheses about potential causes, and applying targeted fixes to restore proper operation. Mastering troubleshooting fundamentals transforms frustrating failures into learning opportunities and dramatically accelerates your robotics development process.

Introduction: Every Roboticist’s Essential Skill

You’ve spent hours assembling your robot, carefully connecting wires, uploading your code, and finally pressing the power button with anticipation. Nothing happens. Or worse, something happens but it’s completely wrong—motors spin backwards, sensors give nonsensical readings, or the robot exhibits bizarre behaviors you never programmed. Welcome to the universal robotics experience: troubleshooting.

Every single roboticist, from absolute beginners to seasoned professionals, spends significant time troubleshooting. It’s not a sign of failure or incompetence—it’s an inherent part of building complex systems with multiple interacting components. The difference between frustrated beginners who abandon projects and successful roboticists who complete them isn’t avoiding problems but developing effective troubleshooting skills.

Troubleshooting is fundamentally a detective’s work. You observe symptoms, gather evidence, form hypotheses about causes, test those hypotheses systematically, and ultimately identify the root cause. Unlike following a tutorial where each step produces expected results, troubleshooting requires critical thinking, patience, and methodical investigation.

This comprehensive guide will equip you with the troubleshooting toolkit every roboticist needs. We’ll explore systematic debugging methodologies, common failure modes and their symptoms, essential diagnostic tools and techniques, and proven strategies for isolating problems quickly. You’ll learn how to approach mysterious failures logically rather than randomly swapping components hoping something works.

More importantly, you’ll discover that effective troubleshooting isn’t just about fixing immediate problems—it’s about building deeper understanding of how your robot works. Each problem you solve teaches you something new about electronics, programming, mechanics, or system integration. The robot that works perfectly teaches you nothing compared to the one that fails in interesting ways, forcing you to understand every detail to get it working.

Whether you’re dealing with a robot that won’t power on, code that crashes mysteriously, sensors providing impossible readings, or motors that won’t spin, the systematic troubleshooting approaches you’ll learn here will guide you from frustration to solution. Let’s transform troubleshooting from a dreaded obstacle into a powerful learning tool and an essential skill in your robotics journey.

The Troubleshooting Mindset: Thinking Like a Detective

Before diving into specific techniques, understanding the proper troubleshooting mindset is crucial. Random component swapping and hopeful code changes waste time and often make problems worse. Effective troubleshooting requires a methodical, analytical approach.

Start with Observations, Not Assumptions

The first principle of effective troubleshooting is gathering accurate observations before jumping to conclusions. What exactly is happening versus what you expected? Be precise in your observations. “The robot doesn’t work” is vague and unhelpful. “The robot powers on (LED illuminates) but motors don’t respond to control inputs” provides actionable information.

Document symptoms completely. Does the problem occur immediately on power-up or only after running for some time? Does it happen consistently or intermittently? Are there patterns to when it fails? Intermittent problems that appear randomly are often the most challenging to debug, but even these usually have underlying patterns if you observe carefully enough.

Avoid the assumption trap. You might assume your code is correct because it worked yesterday, but perhaps you made undocumented changes you’ve forgotten. You might assume components are good because they’re new, but manufacturing defects exist. Question every assumption, especially when stuck. The solution often lies in challenging something you’ve taken for granted.

Divide and Conquer: Isolating Problem Domains

Robots integrate multiple systems: power supply, mechanical structure, electronic circuits, and software. Problems can originate in any domain or their interactions. Effective troubleshooting systematically isolates which domain contains the problem, narrowing the search space dramatically.

Ask yourself: Is this a power problem, a mechanical problem, an electronics problem, or a software problem? Each domain has characteristic symptoms. Power problems typically manifest as complete failures or intermittent operation under load. Mechanical problems show up as physical binding, misalignment, or structural failures. Electronics problems appear as incorrect voltages, failed communication, or damaged components. Software problems produce unexpected behavior patterns, crashes, or logic errors.

Once you’ve identified the likely domain, further subdivide. If it’s an electronics problem, is it in the microcontroller, sensors, actuators, or supporting circuits? If it’s a software problem, is it in initialization, the main loop, specific functions, or interrupt handlers? Each subdivision narrows the focus until you’ve isolated the specific component or code section causing issues.

The divide-and-conquer approach prevents overwhelming complexity. Instead of debugging an entire robot simultaneously, you’re debugging one specific subsystem. This focused approach accelerates problem identification and prevents the confusion of multiple concurrent issues.

Change One Variable at a Time

When testing potential fixes, change only one variable at a time. This fundamental scientific principle applies perfectly to troubleshooting. If you simultaneously change three things and the problem goes away, which change fixed it? You don’t know, and you haven’t truly understood the problem.

Changing one variable at a time creates clear cause-and-effect relationships. You modify something, test the result, and know definitively whether that change affected the problem. This builds genuine understanding rather than lucky fixes you can’t explain or reproduce.

This discipline becomes especially important with software debugging. Resist the urge to simultaneously modify multiple code sections, change compiler settings, and update libraries. Make one change, recompile, test, observe results. If it doesn’t help, revert the change before trying something else. This methodical approach may feel slower initially but actually reaches solutions much faster than chaotic multi-variable changes.

Document Your Process and Findings

Maintain notes during troubleshooting, especially for complex or intermittent problems. Record what you’ve tested, what results you observed, and what hypotheses you’ve ruled out. This documentation prevents repeating unsuccessful tests and helps track progress through complicated debugging sessions.

Your notes don’t need to be formal or elaborate. A simple text file or notebook entry listing “Tested: Swapped motor drivers – no change” or “Observed: Problem only occurs when battery voltage <6V” provides valuable reference. When you return to a problem after a break or find yourself going in circles, these notes ground you in concrete facts.

Documentation becomes especially valuable when seeking help from others. Posting “My robot doesn’t work, help!” on forums produces unhelpful responses. Posting “My robot’s motors don’t respond. I’ve verified power supply is stable at 7.2V, confirmed motor driver receives PWM signals (observed on scope), verified logic levels are correct per datasheet, but motor outputs remain at 0V” demonstrates systematic troubleshooting and provides experts the information needed to suggest next steps.

Power Supply Problems: The Foundation of Everything

Power supply issues cause the majority of beginner robot failures. Understanding how to diagnose power problems systematically prevents wasting time debugging other systems when the root cause is inadequate or unstable power.

The Robot Won’t Power On at All

Complete failure to power on—no lights, no sounds, no signs of life—typically indicates a fundamental power supply problem. Start with the absolute basics before assuming catastrophic component failure.

First, verify your battery or power supply is actually charged and functional. Use a multimeter to measure battery voltage. If you expect 7.4V from a 2-cell LiPo battery but measure 0V, the battery is dead, damaged, or disconnected. Charge the battery fully and retest. This seemingly obvious step is overlooked surprisingly often.

Check all power connections. Are battery terminals making solid contact? Are connectors fully seated? Is the power switch in the on position? Verify continuity from the battery through switches, connectors, and wiring to the power distribution point on your circuit. A loose connector or broken wire interrupts power completely but is easily overlooked visually.

Examine for short circuits. If turning on power immediately causes batteries to heat up or triggers protective fuses, a short circuit is draining current without powering components properly. Disconnect sections of your circuit systematically, testing power on each time to isolate where the short exists. Look for bare wires touching metal chassis, incorrect polarity connections, or solder bridges on circuit boards.

Verify voltage regulators are functioning if your robot uses them. Measure input voltage to the regulator and output voltage. If input is present but output is missing or wrong, the regulator may be damaged, wired incorrectly, or lacking required bypass capacitors. Check regulator datasheets for minimum input voltage requirements—some regulators need several volts higher input than output to function properly.

The Robot Powers On But Shuts Off Immediately or Under Load

This frustrating symptom where your robot appears to power on briefly then dies indicates insufficient current capacity or protection circuits activating. The robot draws initial current successfully but fails when attempting to operate motors or other high-current loads.

Measure your battery voltage under load. Connect a multimeter set to voltage measurement and power on the robot while attempting to activate motors. If voltage drops significantly—say from 7.4V to 5V when motors activate—your battery cannot supply sufficient current. This might mean the battery is undersized for your application, partially discharged, or damaged with high internal resistance.

Check current requirements against battery specifications. Calculate your robot’s current draw: sum the current consumed by the microcontroller, sensors, motor drivers, and motors under load. Compare this to your battery’s discharge rating. A battery rated for 1000mAh at 1C (1 amp) continuous discharge cannot supply 3 amps reliably. You need a battery with higher capacity or higher C-rating (discharge rate multiplier).

Examine for voltage drop in wiring. Thin wires between battery and high-current loads act as resistors, dropping voltage significantly when current flows. Measure voltage at the battery terminals and then at the motor driver input while motors run. If you see a volt or more difference, wire resistance is the problem. Upgrade to heavier gauge wire for power distribution.

Look for automatic reset circuits or low-voltage cutoffs activating. Some battery protection circuits shut off output when voltage drops below a threshold or current exceeds limits. Some microcontrollers have brown-out reset circuits that restart the processor if supply voltage drops too low. These protective features prevent damage but manifest as mysterious shutdowns if triggered.

Intermittent Power Loss or Unexpected Resets

Perhaps most frustrating are robots that work sometimes but randomly lose power or reset. These intermittent failures require careful observation to identify patterns.

Monitor for thermal issues. Components heating up can cause intermittent failures. Voltage regulators reaching thermal shutdown temperature turn off, cool down, turn back on, and repeat this cycle. Touch components carefully (after powering off!) to check for excessive heat. Hot regulators need better heatsinking or lower current draw.

Vibration-induced connection failures plague mobile robots. Connectors that appear secure on a bench come loose when the robot moves. Tape down connectors temporarily or add strain relief to wiring. If intermittent failures disappear, poor connections were the culprit. Improve mechanical connection reliability permanently.

Electrostatic discharge (ESD) from motors or environment can reset microcontrollers. Motor brushes generate electrical noise and voltage spikes. Microcontrollers connected to long wires in dusty or dry environments can experience ESD events. These momentary voltage disturbances cause resets or corruption. Add filtering capacitors near motor power connections and protect microcontroller power with bypass capacitors.

Battery voltage droop during brief high-current events can trigger brown-out resets even when average battery voltage is adequate. A sudden motor current surge pulls voltage down momentarily. Adding large capacitors (100μF to 1000μF) near high-current loads smooths these transients, providing local energy storage that prevents voltage from dropping during surges.

Motor Problems: When Movement Goes Wrong

Motors are among the most common failure points in robotics. They’re mechanical devices subject to wear, electrical devices subject to voltage issues, and high-current loads that stress power supplies.

Motors Don’t Spin at All

When motors receive power and control signals but don’t spin, systematically verify each element of the motor control chain.

Verify power is reaching the motor. Measure voltage at motor terminals when you’re commanding the motor to run. If you measure 0V when expecting motor voltage, the problem is in the motor driver or its connections, not the motor itself. If correct voltage is present but the motor doesn’t spin, suspect the motor.

Check motor driver operation. Motor drivers convert low-current logic signals from microcontrollers into high-current motor control signals. Verify the driver receives correct power supply voltage. Check that control signals from the microcontroller reach the driver inputs. Use a multimeter to measure logic signal voltages—they should switch between logic low (near 0V) and logic high (near VCC).

Test motor driver outputs. Set your multimeter to voltage mode and measure motor driver output while sending commands to run the motor forward, reverse, and stop. Outputs should switch between near 0V, positive supply voltage, and intermediate voltages for PWM speed control. If outputs don’t respond to input commands, the driver may be damaged or wired incorrectly.

Verify motor isn’t mechanically jammed. Disconnect the motor from any mechanical load and try spinning it by hand. It should rotate freely with slight magnetic resistance (cogging). If it won’t turn by hand, mechanical binding prevents operation. If it spins freely by hand but not when powered, the issue is electrical.

Test motors directly. Carefully connect the motor directly to a power supply at appropriate voltage (check motor specifications). If it spins when connected directly but not through the driver, the driver circuit has issues. If it doesn’t spin even with direct power, the motor is damaged—likely burned out from overcurrent or mechanically failed.

Motors Spin But in Wrong Direction or Erratically

Motors that run but behave incorrectly suggest control signal problems rather than power supply issues.

Swapped motor polarity causes reverse rotation. Motor drivers have two output wires per motor. Swapping these wires reverses the motor’s rotation direction. Before diving into complex debugging, try swapping motor leads. If direction corrects, you can either leave it swapped or fix it in software by inverting the direction command.

Incorrect PWM signals cause erratic speeds. Pulse-width modulation controls motor speed by rapidly switching power on and off. If your PWM frequency is too low (typically below 20kHz), motors may whine audibly or run roughly. If PWM duty cycle calculations are incorrect, motors may run slower or faster than intended. Use an oscilloscope to observe PWM signals and verify frequency and duty cycle match your code’s intentions.

Noise and interference corrupt control signals. Long wires carrying PWM or direction signals can pick up electrical noise from motors, causing glitches in control. Twist signal wires with ground wires to reduce noise pickup. Add small capacitors (0.1μF ceramic) across motor terminals to filter motor-generated noise at the source.

Check for software logic errors. Review your code controlling motor direction and speed. Are you accidentally commanding conflicting directions? Do timing issues cause rapid switching between states? Add serial debug output statements showing motor commands to verify your code executes as expected.

Motors Draw Excessive Current or Overheat

Motors consuming more current than expected or running hot indicate mechanical or electrical overload.

Excessive mechanical load forces motors to work harder. If your robot design requires motors to lift heavy loads, climb steep inclines, or overcome high friction, they’ll draw maximum current and heat up. Reduce load by lightening the robot, improving mechanical efficiency, or selecting motors with higher torque ratings.

Voltage too high for motor ratings causes overcurrent. Motors rated for 6V will draw excessive current if powered at 12V. Always verify motor voltage ratings and ensure your power supply matches. If you must use higher voltage than motor rating (which shortens motor life), limit current with appropriate motor drivers and reduce duty cycle.

Stalled or jammed motors draw maximum current continuously. When a motor can’t rotate due to mechanical binding, electrical loading, or holding a heavy load stationary, it draws stall current—often 5-10 times running current. This quickly overheats motors and drains batteries. Implement stall detection in software by monitoring current or checking for rotation, then shut down motors before damage occurs.

Damaged motor windings can short internally, drawing excessive current without producing mechanical power. If a motor that previously worked now draws high current and barely spins or spins weakly, internal damage is likely. Replace the motor.

Sensor Problems: When Your Robot Can’t See

Sensors provide robots with environmental awareness. Sensor failures leave robots blind, causing navigation errors, failed object detection, and unpredictable behavior.

Sensor Provides No Output or Always Maximum/Minimum Output

When sensor readings don’t change or remain stuck at extremes, begin with connection and power verification.

Check sensor power supply voltage. Measure voltage at the sensor’s power pins while the sensor is connected. Many sensors require regulated voltage within a narrow range. A 5V sensor receiving only 4V or 6V may not function correctly or at all. If voltage is outside specifications, add or verify voltage regulation.

Verify communication connections for digital sensors. Sensors using I2C, SPI, UART, or other digital interfaces require proper wiring of data lines, clock lines, and common ground. A single disconnected or mis-wired signal prevents communication completely. Double-check pinout diagrams and verify each connection with a multimeter’s continuity mode.

Test analog sensor outputs with a multimeter. For sensors outputting analog voltage, measure the signal pin with a multimeter set to voltage mode. Try changing what the sensor measures (move your hand in front of a distance sensor, change light hitting a light sensor) and observe if voltage changes. If voltage never changes, suspect sensor damage or incorrect wiring.

Examine pull-up resistors on open-collector or I2C sensors. Some sensors require external pull-up resistors on their signal lines to function. Without these resistors, signals remain at incorrect logic levels. Check sensor datasheets for pull-up requirements and verify they’re installed with correct values.

Sensor Readings Are Erratic or Noisy

Sensors that provide output but with excessive noise or random fluctuations require careful noise analysis.

Electrical noise from motors and switching circuits couples into sensitive sensor lines. Analog sensor signals with high impedance are particularly susceptible. Route sensor wires away from motor power wires. Use shielded cable for long analog signal runs. Add small capacitors (0.1μF to 1μF) between sensor signal and ground to filter high-frequency noise.

Insufficient power supply filtering causes sensor readings to fluctuate with motor current draw. When motors turn on, they create voltage transients and noise on power rails. Sensors sharing the same power supply pick up this noise. Add bulk capacitors (100μF or larger) to your main power supply and local bypass capacitors (0.1μF ceramic) near each sensor’s power pins.

Grounding issues create ground loops that inject noise. Ensure all grounds connect properly and directly. Long ground paths through thin wires create voltage differences between “ground” at different circuit points. Use a star grounding topology where all grounds connect to a single central point, or ensure ground wires are heavy gauge with low resistance.

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) from the environment affects sensors. Operating near sources of RF energy (WiFi routers, cell phones, fluorescent lights) can introduce noise. Shield sensitive circuits in metal enclosures connected to ground. Add ferrite beads to sensor cables to suppress high-frequency interference.

Software averaging helps compensate for noisy sensors. Instead of using raw sensor readings, average multiple consecutive samples to smooth out noise. Implement moving average filters or exponential smoothing in your code. While this doesn’t eliminate noise sources, it makes sensor data usable while you address hardware noise issues.

Sensor Readings Are Incorrect or Don’t Match Reality

When sensors produce output but the values don’t correspond to reality, calibration and configuration issues are likely.

Verify sensor is configured correctly in software. Many digital sensors require initialization commands setting measurement ranges, resolution, sampling rates, and other parameters. If initialization code is missing or incorrect, sensors may use default settings incompatible with your application. Review sensor datasheets and example code to ensure proper configuration.

Calibration may be required for accurate readings. Some sensors ship with generic calibration that provides approximate readings. For precision, you must calibrate against known references. Temperature sensors can be calibrated in ice water (0°C) and boiling water (100°C). Distance sensors can be calibrated against measured distances. Store calibration factors in EEPROM and apply them to raw readings.

Environmental factors affect sensor accuracy. Temperature changes alter sensor characteristics. High humidity affects some sensors. Bright sunlight overwhelms infrared proximity sensors. Magnetic fields interfere with magnetometers. Vibration affects accelerometers. When sensor readings seem wrong, consider environmental conditions and whether they’re within sensor specifications.

Mounting position and orientation matter for directional sensors. Accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers produce different readings depending on their physical orientation. Ensure sensors are mounted aligned with expected axes. If you assume the sensor’s X-axis aligns with robot forward but it’s mounted 90 degrees rotated, all readings will seem wrong until you account for the rotation mathematically.

Check for sensor damage from ESD or overvoltage. While less common than configuration issues, sensors can be permanently damaged by static discharge or voltage spikes. If a sensor worked previously but now gives bizarre readings despite correct configuration, it may be damaged. Test with a known-good replacement sensor to confirm.

Software and Code Problems: Debugging the Logic

Software bugs are insidious because the robot’s hardware might be perfect, but incorrect logic produces wrong behavior. Software debugging requires different tools and techniques than hardware troubleshooting.

The Code Won’t Compile or Upload

Before your code even runs, you must successfully compile and upload it. Compilation and upload errors prevent testing functionality.

Read error messages carefully. Compilation errors include line numbers and descriptions of what’s wrong. Don’t just see “error” and give up—read the actual message. “Expected ‘;’ before ‘Serial'” tells you exactly what to fix. Learn to interpret common error patterns and their meanings.

Common syntax errors include missing semicolons, unmatched brackets or parentheses, and misspelled variable or function names. Modern IDEs often highlight these errors as you type. Count your opening and closing brackets—every { needs a matching }. Enable auto-indent formatting in your IDE to make bracket mismatches visually obvious.

Missing library errors occur when code references functions from libraries that aren’t installed or imported. The error message typically indicates which library is missing. Search for the library name, install it through your IDE’s library manager, and add appropriate include statements at the top of your code.

Upload failures when code compiles successfully suggest communication problems between computer and robot. Verify you’ve selected the correct serial port in your IDE. Ensure the correct board type is selected—uploading Arduino Uno code to an Arduino Mega with wrong board settings often fails. Check that USB drivers are installed for your specific board.

Permission errors on Linux or Mac prevent accessing serial ports. You may need to add your user to the appropriate group (typically ‘dialout’ on Linux) to access USB serial ports. On some systems, you must unplug and replug the USB cable after changing permissions before the system recognizes the change.

The Robot Doesn’t Behave as Expected

Code uploads successfully and runs, but behavior is wrong. This is where real debugging begins.

Start with the simplest possible test. Before debugging complex robot behaviors, verify basic functionality. Can you blink an LED with a simple test program? Can you read a sensor and print values to serial monitor? Can you control a single motor with basic forward/reverse commands? These simple tests confirm hardware works before debugging complex code.

Add liberal debug output statements. Serial.print() or equivalent debug output is your best friend. Print variable values, program flow indicators, and state information throughout your code. When code behaves mysteriously, these debug statements reveal what’s actually happening versus what you think is happening.

Check loop timing and blocking delays. If your main loop contains long delay() calls, the robot can’t respond to sensors or adjust behavior during those delays. Replace blocking delays with non-blocking timing using millis() and state machines. This allows sensor reading and decision making to continue even while waiting for time-based events.

Verify logic conditions evaluate correctly. Add debug output showing the result of if-statement conditions. Print sensor values used in decisions. Often you’ll discover that conditions you expected to be true are false, or vice versa, due to sensor calibration issues, incorrect comparison operators, or logic errors.

Watch for integer overflow and data type problems. Arithmetic with small integers (byte, int) can overflow, producing unexpected results. Timing calculations using millis() require careful handling of rollover every 50 days. Ensure variable types match the ranges of values you’re storing—don’t store angles larger than 255 degrees in a byte variable.

The Code Crashes, Freezes, or Resets

Complete code failures where the microcontroller stops responding, crashes, or resets indicate serious software errors or resource exhaustion.

Stack overflow from excessive recursion or deeply nested function calls crashes programs silently. Microcontrollers have limited stack space for function call return addresses and local variables. Recursive functions or very deep function call chains consume stack until memory is exhausted. Avoid recursion on microcontrollers; use iteration instead.

Memory exhaustion occurs when dynamic memory allocation (malloc, new, or implicit String concatenation) fragments and exhausts available RAM. Microcontrollers have tiny amounts of RAM—often just 2KB. Creating many String objects or dynamically allocating memory in loops can consume all available RAM, causing unpredictable crashes.

Check array bounds carefully. Accessing arrays beyond their allocated size corrupts memory and causes crashes. If you declare an array of 10 elements, valid indices are 0-9. Accessing index 10 or -1 writes to random memory locations. Add bounds checking in loops: for (int i = 0; i < arrayLength; i++), not <=.

Watch for interrupt conflicts and race conditions. If interrupt service routines (ISRs) modify variables that your main code also modifies, unpredictable behavior results without proper synchronization. Keep ISRs short and simple. Use volatile keyword for variables shared between ISRs and main code.

Brown-out resets from voltage drops manifest as random resets during operation. While not strictly a software problem, insufficient power supply decoupling can cause resets that seem like code crashes. Add bypass capacitors near the microcontroller to prevent voltage dips during current surges.

Mechanical Problems: When Physics Doesn’t Cooperate

Mechanical failures are often easier to diagnose than electrical or software issues because they’re physically visible, but they require different troubleshooting approaches.

Robot Moves Sluggishly or Not at Intended Speed

Mechanical resistance prevents motors from achieving full speed or smooth movement.

Check for binding or misalignment in moving parts. Rotate wheels, joints, or mechanisms by hand with power off. They should move smoothly with only slight resistance. If movement is stiff or catches at certain positions, something is binding. Look for misaligned axles, parts rubbing against the chassis, or debris blocking movement.

Excessive friction in bearings or bushings slows movement. If your robot uses simple hole-and-axle connections without proper bearings, friction can be substantial. Upgrade to ball bearings for smoother rotation. Lubricate moving parts appropriately—but be careful not to over-lubricate, which attracts dirt.

Gear mesh issues cause power loss and inefficiency. Gears that aren’t properly meshed bind or skip teeth. Gears meshed too tightly create excessive friction. Gears meshed too loosely cause backlash (play) and potential tooth skipping under load. Adjust gear positioning for smooth meshing with minimal backlash.

Weight distribution affects motor load. An unbalanced robot where weight is concentrated on one side forces motors on that side to work harder. Redistribute weight evenly or select motors with sufficient torque to handle the actual loading.

Voltage drop under load causes motors to spin slower than expected. This is technically an electrical issue but manifests as mechanical symptoms. When motors draw heavy current, voltage drops due to battery internal resistance or wire resistance. Measure motor voltage while running under load and ensure it matches motor ratings.

Structural Failures or Parts Coming Loose

Robots experiencing mechanical failures mid-operation require structural analysis.

Insufficient fastener torque allows parts to work loose over time. Vibration from motors loosens screws and bolts that aren’t adequately tightened. Use appropriate screwdrivers or wrenches to tighten fasteners firmly. Consider threadlocker compound on critical fasteners to prevent loosening.

Wrong fastener selection leads to failure. Screws too short don’t engage enough threads. Screws too long bottom out before clamping parts. Screws too thin shear under load. Choose fasteners with appropriate length, diameter, and thread pitch for your application. When in doubt, oversizing screws slightly improves reliability.

Material selection affects structural integrity. Thin plastic parts may not withstand loads that thicker parts or aluminum would handle easily. If structural failures occur repeatedly in the same location, that part is undersized or made from inadequate material. Reinforce or replace with stronger material.

Joint design matters for load-bearing structures. Cantilevered arms experience large bending moments at their base. Ensure mounting points are rigid and well-supported. Distribute loads across multiple mounting points rather than concentrating stress at a single fastener.

Vibration causes fatigue failures over time. Even if your initial structure is sound, continuous vibration from motors and movement can cause cracks to develop in stress concentration points. Add vibration damping materials (rubber, foam) between vibrating components and structure. Ensure critical structural members are thick enough to resist fatigue.

Using Diagnostic Tools Effectively

While you can troubleshoot many problems through observation alone, diagnostic tools accelerate the process and reveal issues invisible to naked eyes.

The Multimeter: Your Most Essential Tool

A basic multimeter measures voltage, current, resistance, and continuity—providing visibility into electrical systems.

Voltage measurement verifies power is present and at correct levels. Set the multimeter to DC voltage mode (marked V with a straight line) for most robotics measurements. Touch the black probe to ground and red probe to the point you want to measure. Verify battery voltage, regulator outputs, and logic signal levels match expectations.

Continuity testing checks for open circuits and short circuits. Set the multimeter to continuity mode (marked with a sound wave symbol). Touch probes to two points that should be connected. If the multimeter beeps, continuity exists—the path is electrically connected. Use this to verify wires aren’t broken and solder joints are sound. To check for shorts, verify that points that should NOT be connected don’t show continuity.

Resistance measurement identifies component values and detects failures. Measure resistor values to verify they match color codes. Measure motor winding resistance to check for open (infinite resistance) or shorted (near zero resistance) windings. Note: always disconnect components from circuits before measuring resistance to avoid incorrect readings from parallel paths.

Current measurement requires inserting the multimeter in series with the current path. This is trickier than voltage measurement. Set the multimeter to current mode (A or mA), insert it as a break in the wire where you want to measure current, and observe the reading. Start with a high current range (10A) to avoid blowing the multimeter’s fuse, then switch to lower ranges for precision if current is small.

Serial Monitor: Window Into Your Robot’s Mind

Serial communication from your microcontroller to your computer reveals what your code is doing in real-time.

Print debug messages at key points in your code. Add Serial.println() statements showing when your code enters different functions, what sensor values it reads, what decisions it makes, and what commands it sends to actuators. This running commentary reveals program flow and helps identify where behavior diverges from expectations.

Format output for readability. Instead of just printing raw numbers, add labels: Serial.print(“Distance: “); Serial.println(distance); makes output understandable. Use Serial.print() without newline to place related values on the same line for compact display.

Print variable types carefully. Arduino’s Serial.print() assumes integers are decimal by default, but you can specify hexadecimal (HEX) or binary (BIN) format for bit manipulation debugging. For floating-point values, specify decimal places: Serial.println(voltage, 2) shows two decimal places.

Use conditional debug output. Constantly printing from fast loops can overwhelm the serial buffer and slow your program. Print only when values change significantly or at regular intervals (every 100ms rather than every loop iteration). This keeps output manageable while providing sufficient visibility.

Watch for timing-sensitive bugs. Serial communication takes time—sending characters to the serial port introduces delays. If your program seems to work when serial debug output is enabled but fails when you remove the debug statements, timing is likely involved. The debug output delays were masking a race condition or timing-sensitive bug.

Oscilloscope: Seeing Signals in Time

For advanced troubleshooting, especially with timing-sensitive communication or PWM signals, an oscilloscope visualizes electrical signals over time.

Verify PWM waveforms match expectations. An oscilloscope shows PWM frequency (how many on/off cycles per second) and duty cycle (percentage of time the signal is high). If motors behave erratically, examining PWM signals reveals if the problem is incorrect frequency, wrong duty cycle, or noise corrupting the signal.

Debug communication protocols like I2C or SPI. While these work or don’t work from a functional perspective, an oscilloscope reveals why they fail when they do. You might discover that clock signals are incorrect, data setup/hold timing violations occur, or noise corrupts data during transmission.

Observe signal integrity problems. Long wires or fast signal transitions can cause overshoot, undershoot, and ringing on digital signals. While your microcontroller might still interpret the signal correctly, excessive ringing indicates a potential reliability problem. Oscilloscope observation guides adding termination resistors or reducing wire length.

Measure time relationships between signals. Some debugging requires understanding precise timing between multiple signals. Oscilloscopes with multiple channels simultaneously display several signals, showing their time relationships. This helps verify that motor driver input timing meets datasheet specifications or that sensor sampling occurs when signals are stable.

For beginners on a budget, consider USB-based logic analyzers as an affordable alternative. While not true oscilloscopes, logic analyzers capture and display digital signals from multiple channels simultaneously, excellent for debugging communication protocols and timing relationships at a fraction of oscilloscope cost.

Common Problem Patterns and Their Solutions

Experience troubleshooting robots reveals recurring problem patterns. Recognizing these patterns accelerates diagnosis.

The “It Worked Yesterday” Syndrome

When something that previously worked suddenly fails, recent changes are the likely culprit even if they seem unrelated.

Review recent modifications. What changed since it last worked? Did you add new code, connect a new sensor, modify wiring, or change battery? Even small changes can have unexpected effects. If you can’t identify changes, consider your memory might be imperfect—perhaps you made undocumented modifications you’ve forgotten.

Revert to last known working state. If using version control (Git), check out the last working commit. If not using version control (start using it!), restore from backups or manually undo recent changes one by one. When the system works again, you’ve identified which change caused the problem.

Check for accumulated wear or damage. Sometimes “it worked yesterday” failures result not from your changes but from components failing over time. Solder joints crack from vibration, connectors loosen, batteries degrade, motors wear out. Just because it worked yesterday doesn’t mean hardware problems can’t develop.

The “Intermittent Problem” Challenge

Intermittent failures that appear and disappear randomly are frustrating but usually have underlying causes.

Look for thermal issues. If problems appear after running for a while, cooling off restores function, thermal shutdown or temperature-dependent failures are likely. Touch components (carefully!) to identify what’s overheating. Add cooling or reduce current draw.

Suspect mechanical intermittency. Loose connections work sometimes when the robot holds a certain position but fail when vibration or movement shifts the connection. Systematically wiggle connectors and wires while monitoring for failures to identify mechanical connection problems.

Watch for resource exhaustion. Memory leaks or buffer overruns might not crash immediately but cause failures after running for extended periods. Monitor free RAM during operation. If problems appear after specific durations or after certain sequences of operations, resource exhaustion is possible.

Create tests that stress the failure mode. If problems occur randomly, you need to make them occur reliably to debug them. Run extended tests that exercise the robot continuously. Log all sensor data and states to capture the system state when failures occur. Pattern analysis of logs may reveal conditions that trigger failures.

The “Everything Seems Fine But It Doesn’t Work” Paradox

Sometimes all components test good individually, voltages are correct, code compiles without errors, yet the system doesn’t work. Integration problems are the likely cause.

Verify timing and synchronization between components. Even with all components functioning individually, they must interact with correct timing. A sensor might provide valid data, but if your code reads it before the sensor completes measurement, you’ll get stale or invalid results. Review datasheets for timing requirements and verify your code provides adequate setup and hold times.

Check for logic level incompatibility. A 3.3V sensor might output logic high at 2.8V, which falls below the 5V microcontroller’s input high threshold of 3.5V. Each component works fine individually, but together they can’t communicate reliably. Add level shifters or verify all components use compatible logic voltage levels.

Examine load effects and signal impedance. A circuit that works fine when tested with a multimeter (which draws minimal current) might fail under actual load. Sensor outputs might not have sufficient drive strength for long wires or multiple inputs. Add buffer amplifiers or reduce loading.

Consider software integration bugs. Perhaps your motor control code works perfectly, and your sensor reading code works perfectly, but combining them in one program creates conflicts. Shared resources, timing conflicts between different tasks, or interrupt handler interactions can cause failures that don’t appear when testing components separately.

Building a Systematic Troubleshooting Process

The most effective troubleshooting combines all these techniques into a systematic, repeatable process.

Step 1: Gather Complete Information About the Problem

Before changing anything, thoroughly document what’s happening. What exactly is the observable problem? When does it occur? What were you doing when it happened? Can you reproduce it reliably or does it occur intermittently?

Test reproducibility. Try to make the problem happen again intentionally. If you can trigger the problem consistently, debugging becomes much easier. If it’s intermittent, note any patterns—does it happen after running for a certain time, at certain temperatures, or during specific operations?

Document what DOES work alongside what doesn’t. This narrows the problem scope. If motors work but sensors don’t, you’ve eliminated power supply and microcontroller issues (since motors prove those work), focusing investigation on sensor circuits and sensor-reading code.

Step 2: Form Hypotheses About Possible Causes

Based on symptoms, generate plausible explanations. Don’t commit to a single hypothesis; consider multiple possibilities ranked by likelihood.

Use your knowledge of common failures. Power supply problems cause complete failures or erratic behavior. Software bugs cause consistent incorrect behavior. Mechanical issues cause physical binding or structural failures. Match symptoms to typical failure modes to guide hypothesis formation.

Consider interactions between systems. Sometimes problems arise from unexpected interactions. Motor noise interferes with sensors. Software timing conflicts with hardware requirements. Think broadly about how different robot systems affect each other.

Step 3: Test Hypotheses Systematically

Design tests that distinguish between hypotheses. If you suspect either a power supply problem or a software bug, measure supply voltage under load (tests power supply hypothesis) and add debug output showing code execution (tests software hypothesis).

Test one hypothesis at a time. Changing multiple things simultaneously confuses results. If you replace the battery AND modify code AND rewire the motor driver all at once, you won’t know which change fixed the problem if it starts working.

Document test results. Record what you tested and the results. “Replaced battery: no change” eliminates that hypothesis. This documentation prevents circular debugging where you forget what you’ve already tried.

Step 4: Isolate the Problem Through Binary Search

Divide the system in half repeatedly until you’ve isolated the problem component or code section.

For electrical issues, disconnect half the circuit, test if the problem persists, then further subdivide. For software issues, comment out half your code, test, then further subdivide. This binary search approach rapidly narrows the problem location.

Use the “known good” swap technique. Replace suspected components with known-good equivalents. If replacing a sensor fixes the problem, you’ve confirmed the sensor was faulty. If it doesn’t help, the sensor wasn’t the issue.

Step 5: Fix the Root Cause, Not Just Symptoms

Once you’ve identified the problem, understand WHY it occurred and fix the underlying cause.

Avoid band-aid fixes that treat symptoms without addressing causes. If your motor driver overheats, adding a fan cools it but doesn’t address why it’s dissipating excessive power. Maybe you’re exceeding current ratings and need a larger driver, or you have a short circuit consuming current unnecessarily.

Verify the fix solves the problem completely. After implementing a fix, test thoroughly to confirm the problem is resolved. Run extended tests to ensure intermittent issues don’t reappear. Test under various conditions to verify the fix is robust.

Step 6: Document and Learn

Record what you discovered, how you diagnosed it, and how you fixed it. This builds your personal knowledge base for faster troubleshooting in the future.

Share knowledge with the community. Post your problem and solution on forums or blogs. Future roboticists encountering the same issue will benefit from your experience. Teaching others reinforces your own learning.

Analyze what led to the problem. Can you prevent similar issues in the future through better design practices, improved component selection, or more careful assembly? Learning from failures prevents repeating mistakes.

Troubleshooting Checklist for Common Scenarios

Having structured checklists for common scenarios prevents overlooking obvious issues when stress and frustration cloud thinking.

Power-On Failure Checklist

| Check | Test Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Battery charged | Measure battery voltage with multimeter | Charge or replace battery |

| Power switch in ON position | Visual inspection | Turn switch on |

| Battery connected properly | Check connector seating, measure voltage at connection | Re-seat connector, verify polarity |

| No short circuits | Measure resistance between power and ground (should be high) | Locate and fix short circuit |

| Fuses intact | Visual inspection, continuity test | Replace blown fuses, find cause |

| Voltage regulator functioning | Measure input and output voltages | Replace regulator, verify required bypass capacitors |

| Microcontroller receiving power | Measure voltage at VCC and GND pins | Trace and fix power distribution issues |

| Power indicator LED illuminates | Visual inspection | If LED doesn’t light despite correct voltage, LED or resistor may be damaged |

Motor Not Running Checklist

| Check | Test Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Motor driver powered | Measure voltage at driver power pins | Fix power distribution to driver |

| Control signals reaching driver | Measure voltage at driver input pins | Check microcontroller output, wiring |

| Driver outputs responding | Measure voltage at driver outputs while commanding movement | Replace driver if outputs don’t respond; verify driver isn’t in thermal shutdown |

| Motor connected to driver outputs | Continuity test from driver outputs to motor | Fix wiring connections |

| Motor not mechanically jammed | Try rotating by hand with power off | Remove mechanical binding or obstruction |

| Motor functional | Apply voltage directly to motor | Replace motor if damaged |

Sensor Not Working Checklist

| Check | Test Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor powered correctly | Measure voltage at sensor power pins | Fix power connections, add voltage regulation |

| Communication wires connected | Continuity test, verify proper pinout | Correct wiring errors |

| Pull-up resistors installed if required | Check schematic, measure resistance | Add required pull-ups |

| Sensor initialized in code | Review initialization section | Add or correct initialization code |

| Sensor I/O pins configured correctly | Review code, verify pin numbers | Correct pin assignments |

| Reading sensor at appropriate intervals | Review code timing | Adjust reading frequency per datasheet requirements |

When to Ask for Help and How to Do It Effectively

Some problems resist solo troubleshooting despite systematic efforts. Knowing when and how to seek help accelerates solutions.

Recognizing When You Need Assistance

You’ve spent hours debugging with no progress. You’ve tested every hypothesis you can think of. You’ve reviewed code, checked circuits, and measured voltages extensively. At some point, fresh perspective from experienced roboticists provides more value than continued solo debugging.

Complex problems involving multiple interacting systems may exceed beginner knowledge. Problems requiring specialized equipment (oscilloscopes, logic analyzers) you don’t own may require expert assistance. Recognizing your knowledge and resource limitations is wisdom, not weakness.

Sometimes you’re too close to the problem. Fresh eyes from someone who hasn’t been staring at the same circuit for hours often spot obvious issues you’ve overlooked. Don’t hesitate to ask a friend, classmate, or online community to review your setup.

Preparing Effective Help Requests

The quality of help you receive correlates directly with the quality of your question. Vague help requests produce vague unhelpful responses. Detailed, well-structured questions attract expert assistance.

Document your problem completely. Describe what you’re trying to accomplish, what actually happens, what troubleshooting you’ve already done, and what results you observed. Include schematic diagrams or wiring photos, relevant code sections, error messages, and measurements you’ve taken.

Demonstrate you’ve made genuine effort. Forum communities are more willing to help people who’ve tried solving problems themselves first. Showing your troubleshooting process indicates you’re not just asking others to do your work but genuinely stuck despite honest effort.

Ask specific questions rather than “Why doesn’t it work?” Ask “I’m controlling a DC motor with an L298N driver. Motor doesn’t spin despite 12V at driver input and 5V PWM signals at driver inputs. Driver outputs measure 0V. Could the driver be damaged or am I missing something?” This specific question provides context and demonstrates systematic troubleshooting.

Be patient and respectful. Online helpers are volunteers donating their time. They’re not obligated to solve your problems. Express appreciation for assistance offered, even if suggestions don’t immediately solve your issue. Each suggestion adds to your understanding.

Conclusion: Embracing Troubleshooting as Learning

Troubleshooting transforms from frustrating obstacle into powerful learning tool when approached with the right mindset and techniques. Every problem solved deepens your understanding of robotics systems, electronics, programming, and mechanical design. The robot that works perfectly on the first try teaches you nothing compared to the one that presents interesting challenges.

Remember that even expert roboticists spend significant time troubleshooting. The difference isn’t avoiding problems—it’s solving them more efficiently through experience recognizing patterns and systematic diagnostic approaches. Each problem you solve adds to your mental library of failure modes and solutions, accelerating future troubleshooting.

The systematic troubleshooting process you’ve learned here applies beyond robotics to any complex technical system. Gathering information, forming hypotheses, testing systematically, isolating problems through division, and documenting results work for debugging computer software, diagnosing car problems, or fixing home electronics. These are life skills valuable far beyond building robots.

Build your troubleshooting toolkit gradually. You don’t need expensive oscilloscopes and specialized equipment initially. A basic multimeter, your computer’s serial monitor, and systematic thinking solve the vast majority of beginner problems. As you advance, invest in better diagnostic tools that enable more sophisticated debugging.

Develop patience and persistence. Some problems yield quickly to systematic analysis. Others require hours or days of investigation. The most valuable learning often comes from the hardest problems—the ones that force you to understand every detail of your system to identify the subtle issue causing failure.

Document your troubleshooting experiences. Maintain a journal or blog recording interesting problems and their solutions. This serves as your personal reference for future similar issues and helps the broader robotics community. Teaching others through your documentation reinforces your own learning.

Most importantly, don’t let troubleshooting discourage you. Every roboticist faces mysterious failures, confusing symptoms, and seemingly impossible problems. The ones who succeed aren’t necessarily smarter—they’re more persistent, more systematic, and better at learning from failures. Each problem you solve makes you a better roboticist.

Your robot will fail. Components will break. Code will have bugs. Circuits won’t work on the first try. That’s not failure—that’s robotics. The real failure would be giving up when problems appear rather than systematically working through them. With the troubleshooting skills you’ve learned here, you’re equipped to face these challenges confidently and emerge with deeper understanding than any tutorial could provide.

The next time your robot won’t work, take a deep breath, grab your multimeter, open your serial monitor, and start the systematic process. You’re not just fixing a robot—you’re building expertise that will serve you throughout your entire robotics journey and beyond.

Key Takeaways

- Effective troubleshooting requires systematic methodology, not random component swapping or hopeful code changes

- Always start with observations and accurate symptom documentation before jumping to solutions

- Power supply problems cause the majority of beginner failures—verify voltage and current capacity early

- Change only one variable at a time when testing fixes to establish clear cause-and-effect relationships

- Use the divide-and-conquer approach to isolate whether problems are in power, mechanics, electronics, or software domains

- Motors that don’t spin require checking power, driver operation, control signals, and mechanical freedom systematically

- Sensor issues often stem from incorrect wiring, missing pull-up resistors, or lack of proper initialization

- Serial debug output provides invaluable insight into code execution and helps identify software logic errors

- Build a systematic troubleshooting process: gather information, form hypotheses, test systematically, isolate problems, fix root causes, and document findings

- When asking for help, provide complete problem descriptions, demonstrate troubleshooting efforts, and ask specific questions for best results