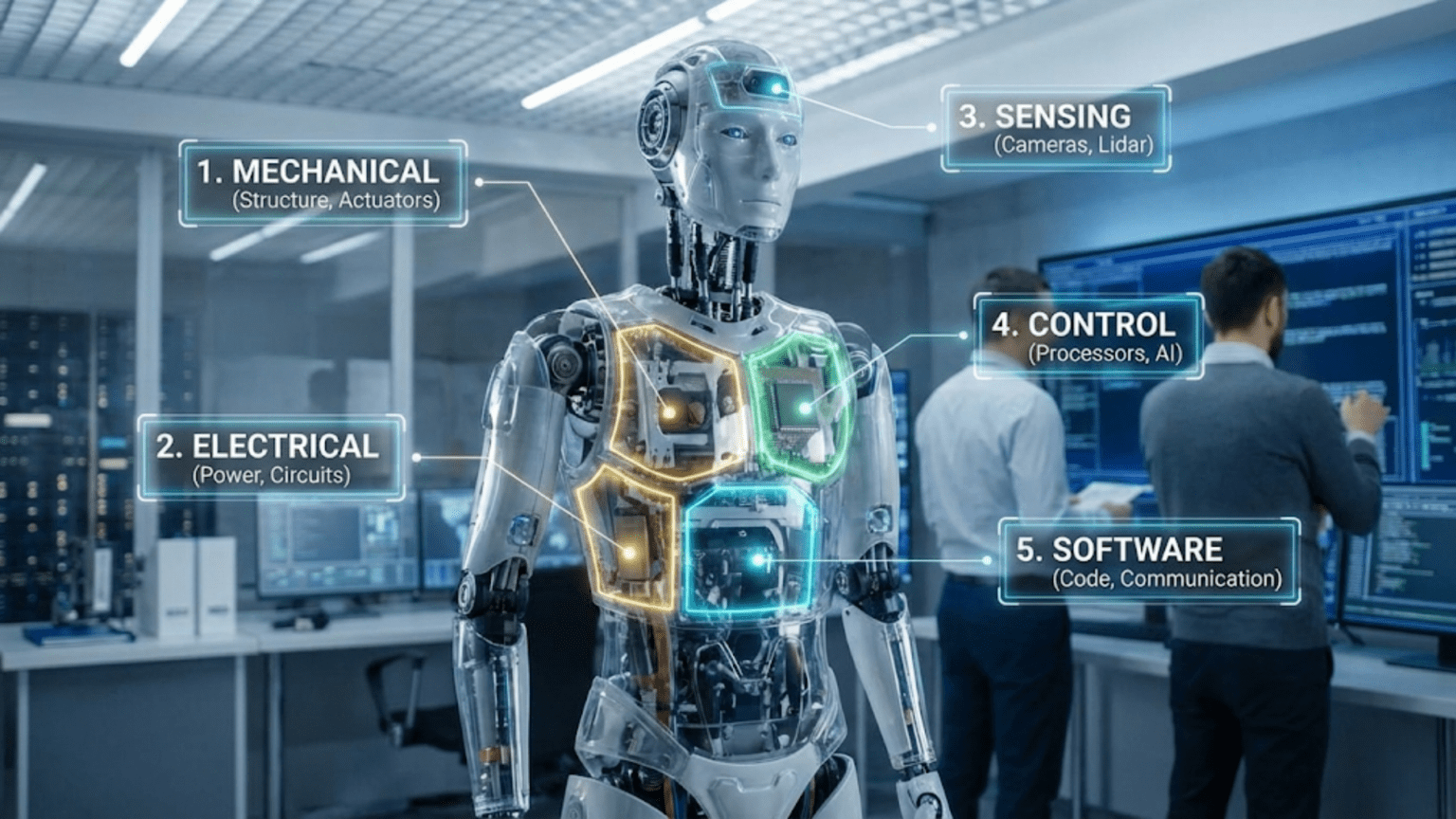

When you look at a completed robot, whether a simple wheeled rover or a sophisticated humanoid machine, you see an integrated system where numerous components work together to produce intelligent behavior. This complexity can feel overwhelming when you are trying to understand how robots actually work or plan your own robot build. However, beneath the surface variations in appearance, capability, and application, every functional robot relies on the same five fundamental systems working in coordination. Understanding these core systems provides a mental framework for analyzing any robot you encounter and designing robots of your own.

These five systems are not arbitrary categories but rather represent essential functional requirements that any robot must satisfy. A robot needs to gather information about its environment, which requires a sensing system. It needs to make decisions about what actions to take, requiring a control system. It must physically interact with the world through an actuation system. All these electronic and mechanical components require electrical energy from a power system. Finally, everything must attach to and be supported by a structural system that holds components in proper relationships while withstanding mechanical forces.

Every robot you will ever build or study, from the simplest beginner project to the most advanced research platform, contains these five systems. Their specific implementations vary enormously based on the robot’s intended function, operating environment, and design constraints, but the fundamental need for each system remains constant. Developing clear understanding of what each system does and how they interconnect transforms robotics from a confusing collection of parts into a comprehensible architecture where each component serves clear purposes.

The Sensing System: Perceiving the Environment

The sensing system encompasses all the components and mechanisms that allow your robot to gather information about its surroundings and its own state. Without sensing capabilities, a robot cannot adapt to changing conditions or respond to environmental features. It becomes merely an automated machine following predetermined sequences regardless of what actually happens in the world around it. Sensing transforms simple automation into true robotics by providing the environmental awareness that enables responsive, adaptive behavior.

Sensors convert physical phenomena into electrical signals that the control system can process. A distance sensor might measure how far away an object sits by emitting ultrasonic pulses and timing their echoes, then converting that time measurement into a voltage that represents distance. A light sensor uses photodiodes to generate current proportional to incident light intensity. A temperature sensor produces voltage that changes with temperature. Each sensor type specializes in detecting particular aspects of the environment or the robot’s internal state.

The sensing system typically includes multiple sensors that provide complementary information. A mobile robot navigating outdoors might combine GPS sensors for absolute position, an inertial measurement unit for orientation and acceleration, wheel encoders for relative movement, and cameras for visual perception of the environment. No single sensor provides complete information, but together they create a more comprehensive picture of the robot’s situation. This multi-sensor approach, called sensor fusion, improves reliability because if one sensor fails or gives ambiguous readings, other sensors can compensate.

Sensor selection represents one of the most important design decisions in robotics. Different tasks require different perceptual capabilities. A line-following robot needs sensors that distinguish between dark and light surfaces but does not need to measure absolute distance. An obstacle-avoiding robot requires distance sensing but might not need color vision. A robotic arm performing assembly tasks needs precise position feedback from encoders but probably does not need to detect environmental temperature. Choosing appropriate sensors that match your robot’s tasks while remaining within budget and power constraints shapes what your robot can accomplish.

Beyond the sensors themselves, the sensing system includes signal conditioning electronics that prepare sensor outputs for the control system. Many sensors produce small voltage changes that need amplification. Analog signals benefit from filtering to remove noise. Some sensors output digital signals requiring specific interface protocols like I2C or SPI. Understanding these signal processing requirements helps you connect sensors effectively and interpret their readings accurately.

The sensing system also addresses sensor placement, mounting, and protection. Sensors must be positioned where they can detect relevant information without mechanical interference from other robot components. Distance sensors need clear lines of sight to obstacles. Cameras require mounting that minimizes vibration blur. Delicate sensors may need protective housings. These physical integration considerations matter as much as the sensors’ technical specifications.

Calibration procedures form another crucial aspect of the sensing system. Most sensors do not provide perfectly accurate readings straight from the factory. Temperature sensors might read slightly high or low. Distance sensors may have offset errors. Color sensors respond differently to various lighting conditions. Calibration processes measure known conditions and adjust sensor readings accordingly, improving accuracy significantly. Many robotics projects fail not because the sensors are inadequate but because nobody bothered to calibrate them properly.

The Control System: Making Decisions

The control system serves as the robot’s brain, processing sensory information and determining appropriate actions. This system transforms the robot from a collection of components into an integrated machine with purposeful behavior. While the sensing system gathers data and the actuation system performs physical actions, the control system provides the intelligence that connects perception to action in meaningful ways.

At the heart of most control systems sits a programmable computer, which might be a simple microcontroller, a more powerful single-board computer, or even a full PC depending on the robot’s computational requirements. This computer runs software that you write, containing all the logic that defines how your robot behaves. The flexibility of software control means you can completely change your robot’s behavior by uploading new code without modifying any hardware.

Control software typically operates in continuous loops that read sensors, process that information, make decisions, and command actuators. This sense-think-act cycle repeats many times per second, allowing the robot to continuously respond to changing conditions. The loop rate, how many times per second this cycle completes, affects how quickly your robot can react to events. A line-following robot might operate at 50 loops per second, while a balancing robot requiring faster reactions might need 200 or more loops per second.

Different control approaches serve different purposes. Reactive control responds immediately to current sensor readings without considering past states or planning future actions. When a distance sensor detects an obstacle close ahead, reactive control immediately turns away. This approach works well for simple behaviors and ensures fast responses but struggles with complex tasks requiring planning or coordination. Deliberative control analyzes situations more thoroughly, considers multiple options, and plans sequences of actions. A robot mapping an unknown environment might use deliberative control to plan efficient exploration paths that cover the entire space systematically.

Most practical robots combine reactive and deliberative control in hybrid architectures. Fast reactive behaviors handle immediate concerns like obstacle avoidance or maintaining balance, while slower deliberative processes plan longer-term actions and coordinate overall behavior. The reactive layer keeps the robot safe and responsive, while the deliberative layer pursues higher-level goals intelligently.

Control algorithms transform sensor readings into motor commands. A simple threshold-based controller might drive motors forward when distance sensors read above 30 centimeters and stop when readings drop below that value. More sophisticated controllers use mathematical relationships between sensor values and desired responses. A proportional controller adjusts motor speeds based on how far sensor readings deviate from target values, producing smoother behavior than simple on-off control. PID controllers add integral and derivative terms that eliminate steady-state errors and dampen oscillations.

The control system manages communication between components. Motor drivers need commands specifying speed and direction. Sensors require trigger signals or continuous polling to provide readings. The control system orchestrates these interactions, ensuring that components receive information when needed and that data flows through the system efficiently.

Memory management becomes important in control systems as robots grow more sophisticated. Your robot might need to remember previous sensor readings for filtering, store maps of explored environments, or maintain history of successful and failed actions for learning. The control system allocates memory appropriately, balancing the competing demands of different subsystems within available resources.

Error handling and safety monitoring represent critical control system responsibilities. What should happen if a sensor fails? How should the robot respond when battery voltage drops dangerously low? What limits prevent motors from overheating or mechanical parts from overextending? The control system monitors for these conditions and implements appropriate protective responses, preventing damage and ensuring safe operation.

The Actuation System: Affecting the Physical World

The actuation system includes all components that enable your robot to create physical motion and exert forces on its environment. While the sensing system gathers information and the control system makes decisions, the actuation system executes those decisions by moving the robot’s body, manipulating objects, or otherwise changing the physical world. Without actuators, even the most sophisticated sensing and control would remain purely abstract, unable to accomplish any physical task.

Electric motors form the most common actuators in robotics, converting electrical energy into rotational motion. Different motor types serve different purposes based on their characteristics. DC motors provide continuous rotation at speeds proportional to applied voltage, making them excellent for wheels and continuous motion. Servo motors incorporate position feedback and control electronics, allowing precise angular positioning ideal for robot arm joints. Stepper motors move in discrete steps, enabling precise positioning without feedback sensors.

Motor selection involves tradeoffs between speed, torque, size, weight, and cost. A small motor spins quickly but provides little torque, while a large motor delivers high torque but weighs more and consumes more power. Gear reduction systems let you trade motor speed for increased torque, allowing smaller motors to move heavier loads at slower speeds. Understanding these relationships helps you choose motors appropriate for your robot’s tasks and constraints.

Beyond motors, other actuator types suit specialized applications. Pneumatic and hydraulic cylinders create powerful linear motion for heavy-duty robots. Solenoids provide fast binary actuation for simple on-off actions like releasing catches or triggering mechanisms. More exotic actuators like piezoelectric elements, shape-memory alloy wires, or electroactive polymers serve niche applications requiring unique characteristics like extreme precision or soft, compliant motion.

Motor drivers form essential parts of the actuation system, providing the interface between low-power control signals and the higher currents motors require. Your microcontroller outputs control signals, typically pulse-width modulation at a few milliamps, but motors might draw several amps. Motor driver circuits amplify these control signals while protecting the control system from motor-generated electrical noise and voltage spikes. H-bridge circuits allow bidirectional motor control, enabling both forward and reverse rotation from a single power supply.

The actuation system includes mechanical transmissions that transfer motor power to useful motion. Gears, belts, chains, and linkages convert motor rotation into the specific motions your robot needs. A robotic arm might use gear trains to increase torque at joints while reducing speed. A mobile robot might use timing belts to synchronize multiple wheels. Understanding mechanical advantage, gear ratios, and transmission efficiency helps you design actuation systems that efficiently convert motor output into desired robot motion.

End effectors represent specialized actuators for manipulation tasks. Grippers open and close to grasp objects, with designs ranging from simple parallel-jaw grippers to complex multi-fingered hands. Vacuum grippers use suction for handling flat objects. Magnetic grippers pick up ferrous materials. Each end effector type suits particular objects and tasks, and many robots use interchangeable end effectors to handle different manipulation requirements.

Actuator control involves more than just turning motors on and off. Speed control through PWM lets you vary motor speeds smoothly. Current limiting prevents motors from drawing excessive power that could damage them or drain batteries quickly. Position control using encoder feedback ensures actuators reach intended positions accurately. The actuation system integrates these control mechanisms to execute the control system’s commands precisely and safely.

The Power System: Providing Energy

The power system supplies electrical energy to all other robot systems. Every electronic component, motor, sensor, and controller requires appropriate voltage and current to function, and the power system delivers this energy reliably. Power system design significantly impacts robot capabilities, determining how long the robot can operate, how much power it can deliver to actuators, and how portability constraints affect overall design.

Batteries provide portable energy storage that enables autonomous robot operation. Different battery chemistries offer different tradeoffs between energy density, power delivery capability, weight, cost, and safety. Lithium polymer (LiPo) batteries deliver high energy density and power output, making them popular for robots requiring substantial power in compact packages. Nickel metal hydride (NiMH) batteries cost less and tolerate abuse better but offer lower energy density. Understanding battery characteristics helps you select appropriate power sources for your robot’s needs.

Battery capacity, measured in amp-hours or milliamp-hours, indicates how much total energy the battery stores. A 2000 mAh battery can theoretically supply 2000 milliamps for one hour, or 1000 milliamps for two hours. In practice, usable capacity depends on discharge rate, temperature, and battery age. Calculating your robot’s power requirements and expected operating time helps you choose batteries with adequate capacity.

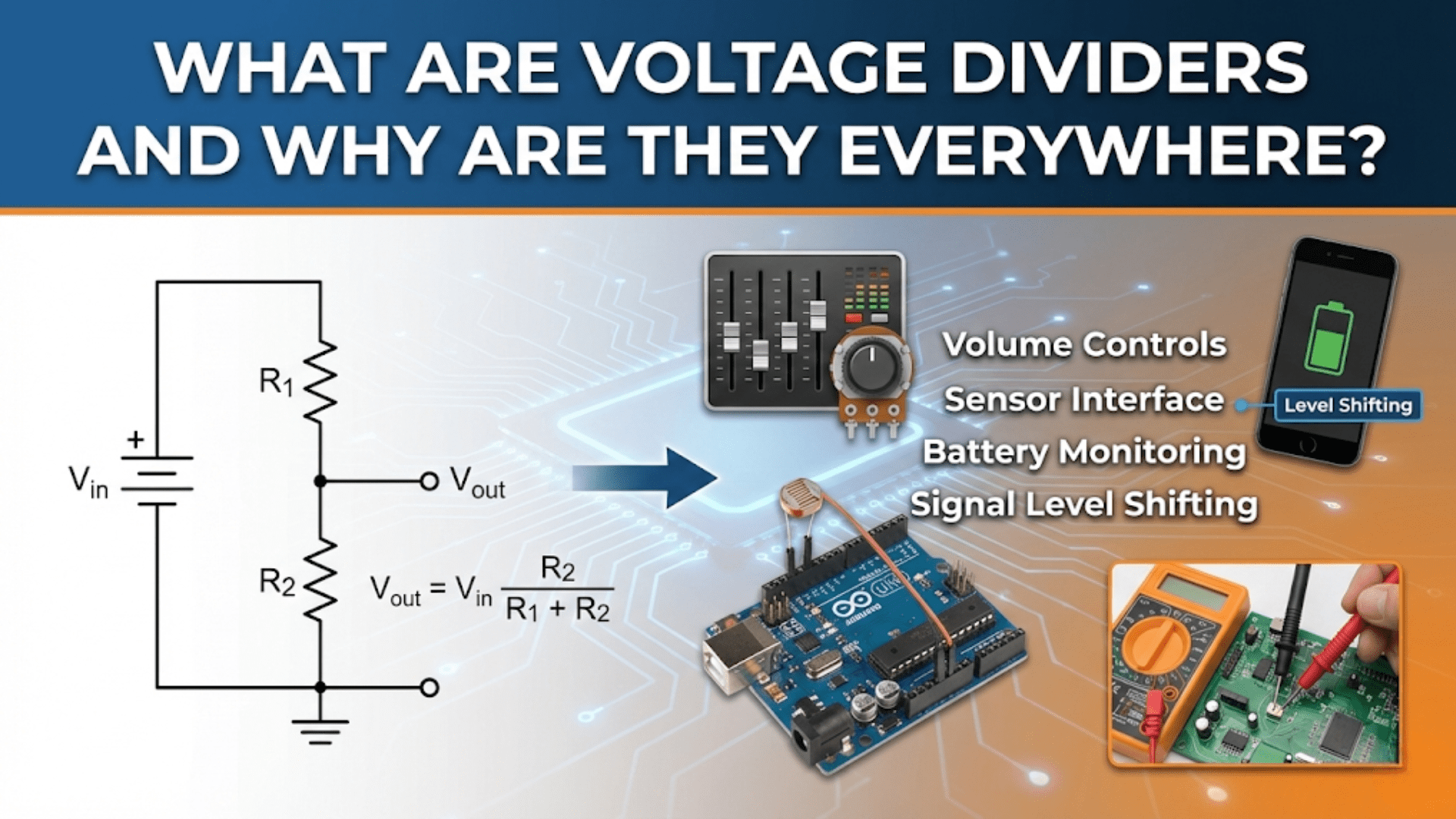

Voltage regulation maintains stable voltage despite batteries’ tendency to drop voltage as they discharge. Most electronic components require specific voltages to operate correctly. A microcontroller might need exactly 5 volts, while motors might run at 12 volts. Voltage regulators convert the battery’s varying voltage into stable, regulated voltages for different subsystems. Linear regulators work simply but waste energy as heat. Switching regulators operate more efficiently, especially when converting between significantly different voltages.

Power distribution systems route energy from batteries to all components safely and efficiently. Circuit protection including fuses, circuit breakers, or electronic current limiters prevents damage from short circuits or component failures. Separate power paths for high-current motors and sensitive electronics prevent motor noise from interfering with control systems. Power switches allow you to turn the robot on and off without physically disconnecting batteries.

Battery management becomes critical for safety and longevity, especially with lithium-based batteries. Overcharging, over-discharging, or excessive current draw can damage batteries, reduce their lifespan, or even cause fires. Battery management systems monitor voltage and current, preventing dangerous conditions. For multi-cell batteries, balancing ensures all cells charge and discharge evenly, maximizing battery life and performance.

Energy efficiency considerations influence robot design at every level. More efficient motors accomplish the same tasks using less power. Optimized control algorithms minimize unnecessary motion and processing. Careful component selection balances capability with power consumption. These efficiency improvements directly translate into longer operating times from the same batteries or equivalent performance from smaller, lighter batteries.

Alternative power sources augment or replace batteries in specific applications. Solar panels can extend operating time for outdoor robots or even enable indefinite operation in sunny conditions. Capacitors and supercapacitors provide brief high-power bursts for demanding actuators. Tethered power from wall outlets or power supplies eliminates battery constraints for stationary robots or testing situations. Some research robots harvest energy from their environment through vibration, heat differentials, or other ambient sources.

The Structural System: Supporting and Protecting

The structural system provides the physical framework that holds all other systems in proper spatial relationships while withstanding mechanical forces during operation. This system determines the robot’s shape, size, and mechanical capabilities. While often overlooked in favor of more exciting electronics and programming, structural design profoundly affects robot performance, durability, and ease of construction.

Chassis or frame components form the structural foundation. These pieces must be rigid enough to prevent flexing that would misalign sensors or mechanical components, yet light enough to not waste payload capacity on structural weight. Material selection involves balancing strength, weight, cost, and ease of fabrication. Plastic sheets work well for small robots and are easily cut and drilled. Aluminum extrusions provide excellent strength-to-weight ratios for medium-sized robots. Steel offers maximum strength for heavy-duty applications. 3D printed parts enable complex custom shapes but vary in strength depending on printing material and settings.

Mounting systems attach components securely while allowing assembly, disassembly, and modification. Standardized hole patterns on chassis plates accept various components in different configurations. Standoffs and spacers create vertical mounting levels. Cable management features route wires neatly and prevent entanglement with moving parts. Well-designed mounting systems make assembly straightforward and enable easy reconfiguration as you modify your robot.

The structural system accommodates mechanical loads from actuators, payload weight, and external forces. Motor mounts must resist torque from motors driving wheels or joints. Manipulator structures must support not just the arm’s weight but also any carried loads. Mobile robot chassis must withstand impacts from collisions or rough terrain. Analyzing expected forces and designing structures with adequate strength prevents mechanical failures that could damage expensive components or create safety hazards.

Vibration isolation and damping protect sensitive components from mechanical noise. Motors and impacts generate vibrations that can blur camera images, interfere with sensor readings, or fatigue structural connections over time. Rubber grommets, foam padding, or specialized vibration dampers reduce transmission of these vibrations to sensitive components. Good structural design considers vibration sources and incorporates appropriate isolation.

Thermal management uses structural elements to dissipate heat from motors, motor drivers, and other components that warm during operation. Heat sinks conduct heat away from hot components and increase surface area for cooling. Strategic ventilation paths allow air circulation. Metal structural elements can serve double duty as heat sinks if properly designed. Preventing excessive temperature buildup improves component reliability and performance.

Enclosures and protective housings shield electronics from dust, moisture, and physical damage. Robot operating environments often contain contaminants that could short circuit boards or corrode connections. Sealed enclosures with gaskets protect against water and dust. Transparent covers allow visual inspection of enclosed components. Impact-resistant materials protect against collisions and drops. Protection level should match the operating environment, from minimal protection for controlled laboratory settings to full weatherproofing for outdoor robots.

Aesthetic and ergonomic considerations influence structural design beyond pure function. Robots that interact with people benefit from friendly, non-threatening appearances. Educational robots often emphasize visible components that help viewers understand how they work. Service robots need interfaces that humans find intuitive and comfortable to use. While function remains primary, thoughtful aesthetic design enhances user acceptance and interaction.

System Integration: Making Components Work Together

Understanding each system individually provides necessary foundation, but creating functional robots requires integrating these five systems into coherent wholes. The art of robotics lies largely in this integration, where components from different systems must cooperate seamlessly. A beautifully designed sensing system accomplishes nothing if the control system cannot process its data. Powerful actuators remain useless if the power system cannot supply adequate current or the structural system cannot withstand the generated forces.

Interface design ensures clean communication between systems. The control system needs standardized ways to command actuators, read sensors, and monitor power status. Well-designed interfaces hide complexity within each system while presenting simple, reliable connections to other systems. This modularity allows you to improve or replace individual systems without completely redesigning your robot.

System-level testing verifies that integration works correctly. Individual component tests confirm that each part functions, but only integrated testing reveals whether they work together properly. Does sensor noise couple into motor drivers and cause erratic behavior? Do motor current spikes reset the microcontroller? Does structural flex misalign sensors? These integration issues only appear when you test the complete system under realistic operating conditions.

Trade-offs and compromises shape integration decisions. Adding more sensors improves perception but increases cost, weight, and power consumption. More powerful motors enable faster motion but require larger batteries and stronger structures. Every design choice ripples through all five systems, requiring balanced decisions that optimize overall robot performance rather than maximizing any single system.

Iterative refinement through testing and modification produces better integrated systems than attempting to perfect designs before building. Your first integration attempt will reveal problems you could not anticipate. Motors might interfere with sensors electromagnetically. Weight distribution might differ from calculations. Battery life might fall short of predictions. Each discovery informs revisions that improve system integration incrementally.

These five fundamental systems—sensing, control, actuation, power, and structure—provide the framework for understanding and designing any robot. Whether you examine a simple line follower or an advanced humanoid, you will find these same systems performing essential functions. Developing clear understanding of what each system does, how systems interact, and why all five are necessary gives you the conceptual foundation for successful robotics work. Every robot you build will exercise these same systems, just implemented in different ways to achieve different goals. This consistency across all robots means that skills you develop on simple projects transfer directly to more complex undertakings, building your capabilities project by project as you master the art of integrating these five fundamental systems into increasingly sophisticated robotic systems.