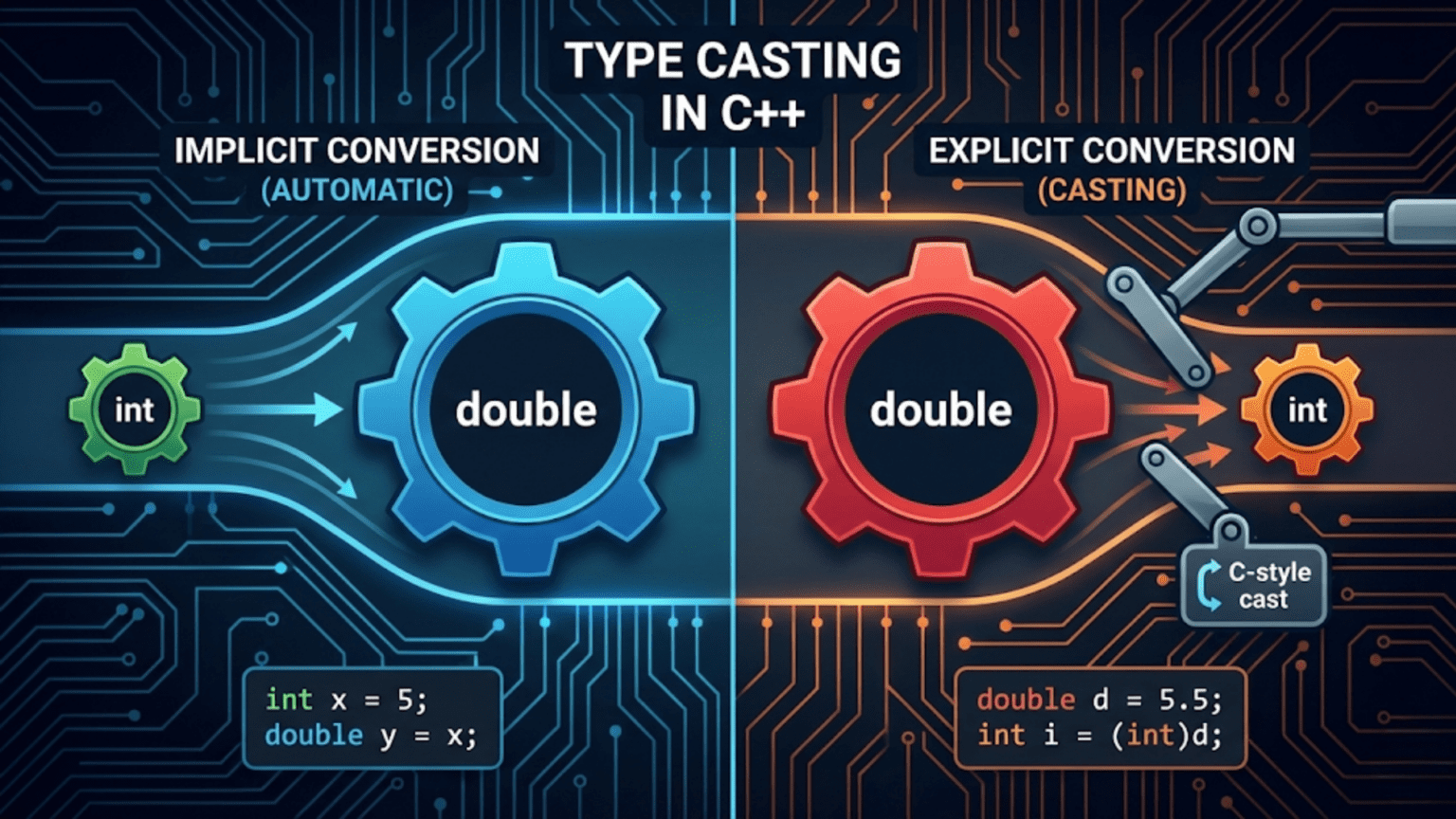

Programs constantly work with different data types—integers, floating-point numbers, characters, custom classes. Sometimes you need to convert values from one type to another, like converting an integer to a floating-point number for division, converting a floating-point result to an integer for display, or converting between related class types in an inheritance hierarchy. C++ performs some conversions automatically when they’re safe and sensible, but requires explicit instructions for conversions that might lose information or change meaning. Understanding type casting—both the conversions that happen automatically and those you must explicitly request—prevents subtle bugs caused by unexpected type conversions while enabling you to perform necessary conversions safely when needed.

Think of type casting like converting between different units of measurement. Converting meters to centimeters happens naturally in your head because it’s safe and obvious—you’re just changing the representation without losing information. That’s like an implicit conversion in C++ where the compiler converts types automatically because the conversion is safe. Converting from centimeters back to meters and rounding to whole numbers requires deliberate thought because you might lose the fractional part. That’s like an explicit cast where you tell the compiler “yes, I know this might lose information, but I want to do it anyway.” Understanding which conversions are automatic and which require explicit casts helps you write code that behaves predictably.

The power of understanding type casting comes from preventing entire categories of bugs while maintaining type safety. Implicit conversions that widen data types (like int to double) typically preserve all information and happen automatically. Conversions that narrow types (like double to int) lose information and require explicit casts, forcing you to acknowledge the potential data loss. C++ provides multiple casting operators—static_cast, dynamic_cast, const_cast, reinterpret_cast—each designed for specific conversion scenarios, making your intentions explicit while catching errors at compile time rather than discovering them at runtime.

Let me start by showing you implicit conversions that C++ performs automatically:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Implicit conversions - happen automatically

// Integer to floating-point (widening - safe)

int intValue = 10;

double doubleValue = intValue; // Implicit conversion

std::cout << "Int to double: " << doubleValue << std::endl;

// Smaller integer type to larger (widening - safe)

short shortValue = 100;

int largerInt = shortValue; // Implicit conversion

std::cout << "Short to int: " << largerInt << std::endl;

// Implicit conversion in arithmetic

int a = 5;

double b = 2.5;

double result = a + b; // a implicitly converted to double

std::cout << "5 + 2.5 = " << result << std::endl;

// Implicit conversion in assignment

double pi = 3.14159;

int truncatedPi = pi; // Warning: narrowing conversion!

std::cout << "Pi truncated to int: " << truncatedPi << std::endl;

// Char to int (implicit)

char letter = 'A';

int asciiValue = letter; // Gets ASCII value

std::cout << "ASCII value of 'A': " << asciiValue << std::endl;

// Boolean conversions

bool flag = true;

int intFlag = flag; // true becomes 1

std::cout << "Boolean to int: " << intFlag << std::endl;

int zero = 0;

bool boolZero = zero; // 0 becomes false, non-zero becomes true

std::cout << "Zero to bool: " << std::boolalpha << boolZero << std::endl;

return 0;

}Implicit conversions happen automatically when the compiler determines the conversion is safe or standard. Converting from smaller integer types to larger ones preserves all information, so it happens implicitly. Converting from integers to floating-point preserves the value (though very large integers might lose precision). Converting from floating-point to integer truncates the decimal part, which is why many compilers warn about this narrowing conversion even though they allow it. Understanding which conversions happen implicitly helps you predict program behavior and spot potential issues.

Integer division demonstrates a common pitfall with implicit conversions where the result might not match expectations:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Integer division - result is integer

int a = 7;

int b = 2;

int resultInt = a / b; // Result: 3 (truncated)

std::cout << "7 / 2 (integers) = " << resultInt << std::endl;

// Mixed division - int promoted to double

double resultMixed = a / 2.0; // 2.0 is double, a converted to double

std::cout << "7 / 2.0 (mixed) = " << resultMixed << std::endl;

// Problem: both operands are int, division happens before assignment

double problemResult = a / b; // Division gives 3, then 3 converted to 3.0

std::cout << "7 / 2 assigned to double = " << problemResult << std::endl;

// Solution: cast one operand to force floating-point division

double correctResult = static_cast<double>(a) / b;

std::cout << "static_cast<double>(7) / 2 = " << correctResult << std::endl;

// Alternative: multiply by 1.0 to force double

double alternativeResult = a * 1.0 / b;

std::cout << "7 * 1.0 / 2 = " << alternativeResult << std::endl;

return 0;

}When both operands of division are integers, C++ performs integer division that discards the remainder, even if you assign the result to a double. The division happens first with integer operands, producing an integer result, then that integer is converted to double for assignment. To get floating-point division, at least one operand must be floating-point, which you can ensure through explicit casting.

The static_cast operator performs explicit conversions that are checked at compile time for validity:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Numeric conversions with static_cast

double pi = 3.14159;

int intPi = static_cast<int>(pi); // Explicit truncation

std::cout << "Pi as int: " << intPi << std::endl;

// Converting between numeric types

float floatValue = 2.718f;

double doubleValue = static_cast<double>(floatValue);

std::cout << "Float to double: " << doubleValue << std::endl;

// Converting between signed and unsigned

int signedInt = -5;

unsigned int unsignedInt = static_cast<unsigned int>(signedInt);

std::cout << "Signed to unsigned (be careful!): " << unsignedInt << std::endl;

// Character conversions

int charCode = 65;

char character = static_cast<char>(charCode);

std::cout << "ASCII 65 as char: " << character << std::endl;

// Pointer conversions (related types)

int value = 42;

void* voidPtr = static_cast<void*>(&value); // int* to void*

int* intPtr = static_cast<int*>(voidPtr); // void* back to int*

std::cout << "Value through void*: " << *intPtr << std::endl;

return 0;

}The static_cast operator makes conversions explicit, documenting your intention clearly. It performs compile-time checking to ensure the conversion makes sense—you cannot static_cast between completely unrelated types. The syntax static_cast<target_type>(expression) clearly shows what conversion you’re performing, making code more maintainable than C-style casts. Use static_cast whenever you need explicit conversion between numeric types or between related pointer types.

Let me show you a practical example demonstrating when different casting operators are appropriate:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <cmath>

class Temperature {

private:

double celsius;

public:

Temperature(double c) : celsius(c) {}

double getCelsius() const { return celsius; }

double getFahrenheit() const {

return celsius * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0;

}

// Explicit conversion operator

explicit operator double() const {

return celsius;

}

};

class Statistics {

public:

static double calculateAverage(const std::vector<int>& values) {

if (values.empty()) return 0.0;

// Need to cast to avoid integer division

int sum = 0;

for (int value : values) {

sum += value;

}

// Cast to double to get accurate average

return static_cast<double>(sum) / values.size();

}

static int roundToInt(double value) {

// Explicit conversion from double to int

return static_cast<int>(std::round(value));

}

static void displayPercentage(int numerator, int denominator) {

if (denominator == 0) {

std::cout << "Undefined" << std::endl;

return;

}

// Cast to double for accurate percentage

double percentage = (static_cast<double>(numerator) / denominator) * 100.0;

std::cout << numerator << "/" << denominator << " = "

<< percentage << "%" << std::endl;

}

};

class Point {

private:

int x, y;

public:

Point(int xVal, int yVal) : x(xVal), y(yVal) {}

double distanceFromOrigin() const {

// Implicit conversion of int to double in calculation

return std::sqrt(x * x + y * y);

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ")";

}

// Get x as percentage of total

double getXPercentage(int total) const {

return (static_cast<double>(x) / total) * 100.0;

}

};

int main() {

// Temperature conversions

Temperature temp(25.0);

std::cout << "Temperature: " << temp.getCelsius() << "°C = "

<< temp.getFahrenheit() << "°F" << std::endl;

// Explicit conversion operator requires static_cast

double celsius = static_cast<double>(temp);

std::cout << "Celsius value: " << celsius << std::endl;

std::cout << std::endl;

// Statistics with casting

std::vector<int> scores = {85, 92, 78, 95, 88};

double average = Statistics::calculateAverage(scores);

std::cout << "Average score: " << average << std::endl;

std::cout << "Rounded average: " << Statistics::roundToInt(average) << std::endl;

std::cout << std::endl;

Statistics::displayPercentage(17, 20);

Statistics::displayPercentage(3, 4);

std::cout << std::endl;

// Point with implicit and explicit conversions

Point p(3, 4);

p.display();

std::cout << " distance from origin: " << p.distanceFromOrigin() << std::endl;

std::cout << "X as percentage of 10: " << p.getXPercentage(10) << "%" << std::endl;

return 0;

}This example demonstrates appropriate use of static_cast throughout a realistic application. The Statistics class uses static_cast to convert integers to doubles for accurate division and percentage calculations. The Temperature class uses an explicit conversion operator that requires static_cast to use. The Point class combines implicit conversions in mathematical operations with explicit casts where precision matters. Each cast is necessary and clearly documents the conversion being performed.

C++ provides specialized casting operators for specific scenarios that static_cast cannot handle. The dynamic_cast operator performs runtime type checking for polymorphic classes:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Animal {

protected:

std::string name;

public:

Animal(const std::string& n) : name(n) {}

virtual ~Animal() {} // Virtual destructor needed for polymorphism

virtual void makeSound() const {

std::cout << name << " makes a sound" << std::endl;

}

};

class Dog : public Animal {

public:

Dog(const std::string& n) : Animal(n) {}

void makeSound() const override {

std::cout << name << " barks: Woof!" << std::endl;

}

void fetch() const {

std::cout << name << " fetches the ball" << std::endl;

}

};

class Cat : public Animal {

public:

Cat(const std::string& n) : Animal(n) {}

void makeSound() const override {

std::cout << name << " meows: Meow!" << std::endl;

}

void climb() const {

std::cout << name << " climbs the tree" << std::endl;

}

};

void interactWithAnimal(Animal* animal) {

animal->makeSound();

// Try to cast to Dog

Dog* dog = dynamic_cast<Dog*>(animal);

if (dog != nullptr) {

std::cout << "It's a dog!" << std::endl;

dog->fetch();

}

// Try to cast to Cat

Cat* cat = dynamic_cast<Cat*>(animal);

if (cat != nullptr) {

std::cout << "It's a cat!" << std::endl;

cat->climb();

}

}

int main() {

Dog myDog("Buddy");

Cat myCat("Whiskers");

std::cout << "=== Interacting with Dog ===" << std::endl;

interactWithAnimal(&myDog);

std::cout << "\n=== Interacting with Cat ===" << std::endl;

interactWithAnimal(&myCat);

return 0;

}The dynamic_cast operator works only with polymorphic types (classes with at least one virtual function) and performs runtime type identification. When casting pointers, dynamic_cast returns nullptr if the conversion fails. When casting references, it throws std::bad_cast exception on failure. This runtime checking enables safe downcasting in inheritance hierarchies, allowing you to determine the actual type of an object pointed to by a base class pointer.

The const_cast operator adds or removes const qualification, though using it requires careful thought:

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

// Legacy API that doesn't use const (poorly designed)

void legacyPrint(char* str) {

std::cout << "Legacy: " << str << std::endl;

}

// Modern function with const

void modernFunction(const char* str) {

// Need to call legacy function that doesn't accept const

// Use const_cast to remove const (dangerous but sometimes necessary)

char* nonConstStr = const_cast<char*>(str);

legacyPrint(nonConstStr); // Hope it doesn't modify!

}

class Configuration {

private:

mutable int accessCount; // mutable allows modification in const methods

int value;

public:

Configuration(int v) : accessCount(0), value(v) {}

int getValue() const {

accessCount++; // Allowed because it's mutable

return value;

}

// Sometimes const_cast is needed for const-correct code

void demonstrateConstCast() const {

// Cannot modify non-mutable members in const method

// value = 10; // Error!

// But with const_cast (generally bad practice)

Configuration* nonConstThis = const_cast<Configuration*>(this);

nonConstThis->value = 10; // Now allowed (breaks const contract!)

}

};

int main() {

const char* message = "Hello";

modernFunction(message);

Configuration config(42);

std::cout << "Value: " << config.getValue() << std::endl;

return 0;

}The const_cast operator should be used sparingly, primarily when interfacing with legacy APIs that don’t properly use const. Using const_cast to modify genuinely const data causes undefined behavior. The mutable keyword provides a better solution for members that need modification in const methods. Const_cast exists for those rare situations where you must remove const, but every use should be carefully considered and documented.

The reinterpret_cast operator performs low-level reinterpretation of bit patterns, which is rarely needed and potentially dangerous:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int value = 65;

// Reinterpret integer bits as character (not recommended)

char* charPtr = reinterpret_cast<char*>(&value);

std::cout << "First byte as char: " << *charPtr << std::endl;

// Converting pointer to integer (platform-specific)

long long addressValue = reinterpret_cast<long long>(&value);

std::cout << "Address as integer: " << addressValue << std::endl;

// Unrelated pointer types (dangerous!)

double doubleValue = 3.14;

int* intPtr = reinterpret_cast<int*>(&doubleValue);

// Using *intPtr here would interpret double bits as int (probably nonsense)

return 0;

}The reinterpret_cast performs conversions between unrelated pointer types or between pointers and integers. It simply reinterprets the bit pattern without any conversion. This is extremely dangerous and should be used only in very specific low-level programming scenarios like hardware interfacing or implementing allocators. For almost all normal programming, reinterpret_cast is the wrong tool.

C-style casts work but are discouraged in modern C++ because they can perform any combination of static_cast, const_cast, and reinterpret_cast without clear intent:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

double pi = 3.14159;

// C-style cast (old style)

int intPi = (int)pi;

// Modern C++ style (preferred)

int intPi2 = static_cast<int>(pi);

// C-style cast can do dangerous things

const int constValue = 42;

int* dangerousPtr = (int*)&constValue; // Removes const without warning

// Modern equivalent makes danger explicit

int* explicitPtr = const_cast<int*>(&constValue);

std::cout << "C-style cast: " << intPi << std::endl;

std::cout << "static_cast: " << intPi2 << std::endl;

return 0;

}C-style casts use syntax like (type)expression and will perform whatever combination of casts necessary to make the conversion work. This flexibility is dangerous because you cannot tell from the cast what conversion is actually happening. Modern C++ casting operators make intentions explicit—static_cast for standard conversions, dynamic_cast for polymorphic downcasting, const_cast for const manipulation, reinterpret_cast for low-level reinterpretation. Always prefer named casting operators over C-style casts.

Common mistakes with type casting include unnecessary casts that clutter code, using C-style casts instead of named operators, forgetting to cast when dividing integers for floating-point results, using reinterpret_cast when static_cast would work, and assuming dynamic_cast always succeeds without checking the result. Another subtle error is relying on implicit conversions between signed and unsigned integers, which can produce unexpected results.

Key Takeaways

Type casting converts values from one type to another, with implicit conversions happening automatically for safe widening conversions and explicit casts required for narrowing conversions that might lose information. Understanding which conversions are implicit helps predict program behavior and spot potential issues, particularly with integer division where both operands being integers produces an integer result even when assigned to floating-point variables.

The static_cast operator performs explicit conversions with compile-time checking, making intentions clear while ensuring conversions make sense. Use static_cast for numeric conversions, conversions between related pointer types, and any explicit conversion between compatible types. The dynamic_cast operator performs runtime type checking for polymorphic downcasting in inheritance hierarchies, returning nullptr or throwing exceptions when conversions fail, enabling safe type identification.

The const_cast operator adds or removes const qualification and should be used sparingly, primarily when interfacing with legacy APIs. The reinterpret_cast operator performs dangerous low-level bit pattern reinterpretation and should almost never be used in normal code. C-style casts are discouraged because they can perform any combination of conversions without making intentions clear. Always prefer named casting operators that explicitly document what conversion you’re performing, making code more maintainable and catching errors at compile time.