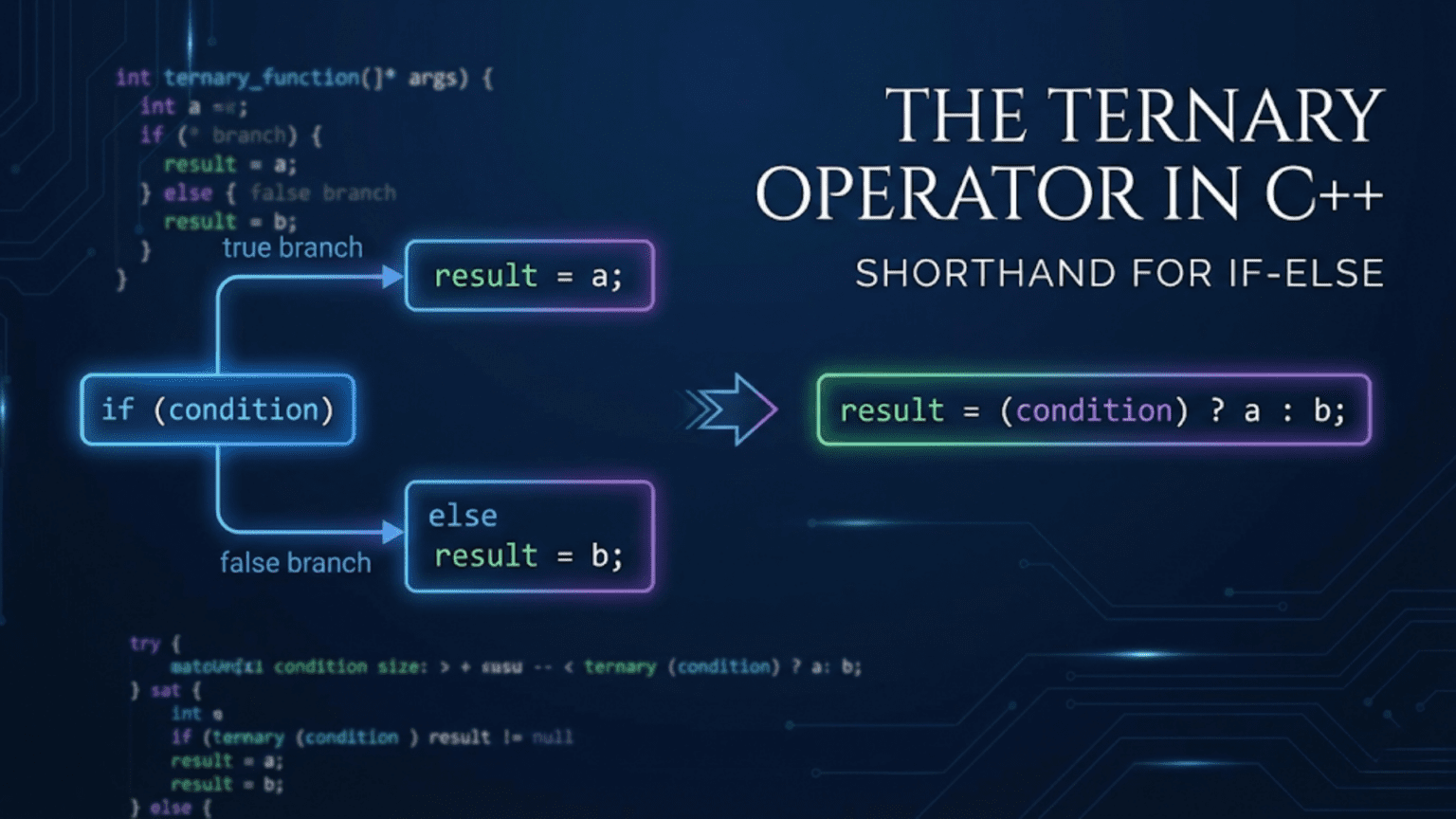

When you write code that needs to choose between two values based on a condition, you typically reach for an if-else statement. But if-else statements are statements—they control program flow but don’t produce values directly. What if you need a conditional value to assign to a variable, pass to a function, or use in a calculation? You could write a full if-else block, but that feels verbose for simple choices. The ternary operator solves this elegantly by providing a compact way to choose between two values based on a condition, creating an expression that produces a result rather than a statement that controls flow. Understanding the ternary operator enables writing more concise code for simple conditional selections while knowing when its brevity enhances or harms readability.

Think of the ternary operator like a traffic signal for values. When you approach an intersection, the light tells you whether to go or stop—one condition, two possible outcomes. The ternary operator works similarly: you provide a condition, and based on whether it’s true or false, you get one of two values. Just as you wouldn’t use a complex traffic interchange for a simple yes-or-no decision, the ternary operator works best for straightforward choices between two values. For complex decisions with multiple branches or side effects, traditional if-else statements remain clearer.

The power of the ternary operator comes from treating conditional selection as an expression rather than a statement. This enables patterns that would otherwise require awkward temporary variables or repeated code. You can initialize const variables conditionally, build expressions with conditional components, and write more functional-style code where computations produce values rather than mutating state. Understanding when the ternary operator enhances code versus when it obscures meaning represents an important step toward writing idiomatic, maintainable C++.

Let me start by showing you the basic syntax and comparing it to equivalent if-else statements:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int age = 20;

// Traditional if-else statement

std::string status1;

if (age >= 18) {

status1 = "adult";

} else {

status1 = "minor";

}

std::cout << "Status (if-else): " << status1 << std::endl;

// Ternary operator - more concise

std::string status2 = (age >= 18) ? "adult" : "minor";

std::cout << "Status (ternary): " << status2 << std::endl;

// The syntax: condition ? value_if_true : value_if_false

// Using ternary directly in output

std::cout << "Age category: " << ((age >= 18) ? "adult" : "minor") << std::endl;

// With numbers

int score = 85;

char grade = (score >= 60) ? 'P' : 'F'; // Pass or Fail

std::cout << "Grade: " << grade << std::endl;

// Choosing between numeric values

int temperature = 75;

int thermostatSetting = (temperature > 72) ? 68 : 74;

std::cout << "Thermostat set to: " << thermostatSetting << std::endl;

return 0;

}The ternary operator has the syntax condition ? value_if_true : value_if_false. The condition is evaluated first. If it’s true, the expression produces value_if_true. If it’s false, the expression produces value_if_false. This creates an expression that evaluates to a single value, which can be assigned to variables, passed to functions, or used in larger expressions. The parentheses around the condition are optional but often improve readability by clearly grouping the condition.

The ternary operator truly shines when initializing const variables that depend on a condition:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

int main() {

int userAge = 25;

bool isPremiumMember = true;

// Initializing const variable with ternary

const int discountPercent = (userAge >= 65 || userAge < 18) ? 20 : 10;

std::cout << "Discount: " << discountPercent << "%" << std::endl;

// Multiple conditions in ternary

const std::string membershipLevel = isPremiumMember ? "Premium" : "Standard";

std::cout << "Membership: " << membershipLevel << std::endl;

// Would require if-else with temporary variable otherwise

// int temp;

// if (condition) {

// temp = value1;

// } else {

// temp = value2;

// }

// const int discountPercent = temp;

// Using in function arguments

int basePrice = 100;

double finalPrice = basePrice * (1.0 - (discountPercent / 100.0));

std::cout << "Final price: $" << finalPrice << std::endl;

return 0;

}Because const variables must be initialized when declared and cannot be assigned to afterwards, the ternary operator provides an elegant solution for conditional initialization. Without it, you’d need a temporary non-const variable or a separate initialization function. The ternary operator enables direct initialization based on conditions, keeping variables const while maintaining code clarity.

The ternary operator works well in return statements and function arguments where you need to conditionally select a value:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cmath>

// Using ternary in return statement

int getAbsoluteValue(int value) {

return (value >= 0) ? value : -value;

}

std::string getGradeDescription(int score) {

return (score >= 90) ? "Excellent" :

(score >= 80) ? "Good" :

(score >= 70) ? "Satisfactory" :

(score >= 60) ? "Passing" : "Failing";

}

double calculateDiscount(double price, bool isPremium) {

// Ternary in calculation

return price * (isPremium ? 0.20 : 0.10);

}

int main() {

std::cout << "Absolute value of -15: " << getAbsoluteValue(-15) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Absolute value of 42: " << getAbsoluteValue(42) << std::endl;

std::cout << "\nGrade for 85: " << getGradeDescription(85) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Grade for 72: " << getGradeDescription(72) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Grade for 55: " << getGradeDescription(55) << std::endl;

double price = 100.0;

std::cout << "\nStandard discount: $" << calculateDiscount(price, false) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Premium discount: $" << calculateDiscount(price, true) << std::endl;

// Using ternary in function call

std::cout << "\nMax of 10 and 20: " << std::max((10 > 20) ? 10 : 20, 15) << std::endl;

return 0;

}Using the ternary operator in return statements creates concise single-expression functions. The getAbsoluteValue function demonstrates a simple case where the ternary operator makes the function body a single expression. The getGradeDescription shows a chain of ternary operators handling multiple conditions, though this starts to approach the limit of readability. The calculateDiscount function shows using ternary operators within larger expressions, selecting multipliers based on conditions.

Let me show you practical examples demonstrating when the ternary operator improves code versus when it makes code harder to read:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class BankAccount {

private:

std::string accountNumber;

double balance;

bool isPremium;

public:

BankAccount(const std::string& accNum, double initialBalance, bool premium)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(initialBalance), isPremium(premium) {}

// Good use: simple conditional selection

double getTransactionFee() const {

return isPremium ? 0.0 : 2.50;

}

// Good use: choosing between two values

std::string getAccountType() const {

return isPremium ? "Premium" : "Standard";

}

bool withdraw(double amount) {

// Good use: simple validation

double fee = getTransactionFee();

double total = amount + fee;

if (total > balance) {

return false;

}

balance -= total;

std::cout << "Withdrew $" << amount

<< (fee > 0 ? " (fee: $" + std::to_string(fee) + ")" : "")

<< std::endl;

return true;

}

void displayBalance() const {

std::cout << "Account: " << accountNumber << std::endl;

std::cout << "Type: " << getAccountType() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

// Good use: conditional message

std::cout << (balance < 100 ? "Warning: Low balance" : "Balance OK") << std::endl;

}

// Example: when ternary might be too much

std::string getBalanceStatus() const {

// This is getting complex - might be clearer as if-else

return (balance < 0) ? "Overdrawn" :

(balance < 100) ? "Low" :

(balance < 1000) ? "Normal" :

(balance < 10000) ? "Good" : "Excellent";

}

};

class Product {

private:

std::string name;

double price;

int stock;

public:

Product(const std::string& n, double p, int s)

: name(n), price(p), stock(s) {}

// Good use: simple calculation modifier

double getPrice(int quantity) const {

double basePrice = price * quantity;

// Apply discount for bulk orders

return quantity >= 10 ? basePrice * 0.9 : basePrice;

}

// Good use: conditional string building

std::string getStockStatus() const {

return (stock > 0) ?

(std::to_string(stock) + " in stock") :

"Out of stock";

}

void display() const {

std::cout << name << ": $" << price << std::endl;

std::cout << "Status: " << getStockStatus() << std::endl;

// Good use: conditional formatting

std::cout << (stock > 0 ? "Available" : "Unavailable")

<< " for purchase" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

BankAccount account1("ACC001", 1500.0, true);

BankAccount account2("ACC002", 50.0, false);

std::cout << "=== Premium Account ===" << std::endl;

account1.displayBalance();

account1.withdraw(100);

std::cout << std::endl;

std::cout << "=== Standard Account ===" << std::endl;

account2.displayBalance();

account2.withdraw(20);

std::cout << std::endl;

Product laptop("Laptop", 999.99, 5);

Product mouse("Mouse", 29.99, 0);

std::cout << "=== Products ===" << std::endl;

laptop.display();

std::cout << "Price for 1: $" << laptop.getPrice(1) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Price for 12 (with discount): $" << laptop.getPrice(12) << std::endl;

std::cout << std::endl;

mouse.display();

return 0;

}This example demonstrates appropriate uses of the ternary operator. Simple choices between two values—like fee amounts, status strings, or formatting options—work well with ternary operators and improve code conciseness. The withdraw method shows using a ternary operator to conditionally include text in output. The getBalanceStatus method demonstrates where a chain of ternary operators starts to hurt readability and might be better as an if-else chain or switch statement.

Nested ternary operators require special care because they can quickly become unreadable:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int score = 75;

// Nested ternary - hard to read

std::string grade1 = (score >= 90) ? "A" :

(score >= 80) ? "B" :

(score >= 70) ? "C" :

(score >= 60) ? "D" : "F";

// Same logic with if-else - more readable for complex cases

std::string grade2;

if (score >= 90) {

grade2 = "A";

} else if (score >= 80) {

grade2 = "B";

} else if (score >= 70) {

grade2 = "C";

} else if (score >= 60) {

grade2 = "D";

} else {

grade2 = "F";

}

std::cout << "Grade (nested ternary): " << grade1 << std::endl;

std::cout << "Grade (if-else): " << grade2 << std::endl;

// Simple nesting is okay

int value = 15;

std::string category = (value < 0) ? "negative" :

(value == 0) ? "zero" : "positive";

std::cout << "Category: " << category << std::endl;

// But this is too much

int a = 5, b = 3, c = 8;

int result = (a > b) ? ((a > c) ? a : c) : ((b > c) ? b : c);

std::cout << "Maximum of " << a << ", " << b << ", " << c << ": " << result << std::endl;

// Clearer version

int max = a;

if (b > max) max = b;

if (c > max) max = c;

std::cout << "Maximum (clear version): " << max << std::endl;

return 0;

}Nested ternary operators create right-to-left associativity that can be confusing. The expression a ? b : c ? d : e is parsed as a ? b : (c ? d : e), not (a ? b : c) ? d : e. This parsing, combined with the visual complexity of multiple question marks and colons, makes nested ternary operators difficult to read. For chains of conditions, if-else statements typically communicate intent more clearly. Reserve nested ternary operators for cases where there’s exactly one level of nesting and the logic remains obvious at a glance.

Understanding type compatibility with ternary operators helps avoid compilation errors:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

int main() {

bool condition = true;

// Both values must have compatible types

auto result1 = condition ? 10 : 20; // Both int - OK

auto result2 = condition ? 1.5 : 2.5; // Both double - OK

// Different but compatible types - converts to common type

auto result3 = condition ? 10 : 2.5; // int and double -> double

std::cout << "Result3 (int or double): " << result3 << std::endl;

// String literals work

const char* result4 = condition ? "yes" : "no"; // Both string literals

// std::string works

std::string result5 = condition ? std::string("yes") : std::string("no");

// Or with string literals and implicit conversion

std::string result6 = condition ? "yes" : "no";

// Incompatible types cause errors

// auto result7 = condition ? 10 : "text"; // Error! int vs const char*

// Solution: ensure both sides have same type

std::string result8 = condition ? "10" : "text"; // Both const char* (converts to string)

return 0;

}The ternary operator requires both value branches to have compatible types. When types differ, C++ attempts to find a common type both can convert to. If no common type exists, compilation fails. This type requirement ensures the ternary expression has a well-defined type that can be used consistently. When working with different types, ensure both branches can convert to the desired result type, either implicitly or through explicit casts.

The ternary operator evaluates only one of its value expressions, not both:

#include <iostream>

int increment(int& value) {

return ++value;

}

int decrement(int& value) {

return --value;

}

int main() {

int counter = 10;

bool increase = true;

// Only the selected branch is evaluated

int result = increase ? increment(counter) : decrement(counter);

std::cout << "Counter: " << counter << std::endl; // 11, not 9

std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;

// Demonstrates short-circuit evaluation

int value = 5;

int safe = (value != 0) ? (100 / value) : 0; // Division only happens if value != 0

std::cout << "Safe division: " << safe << std::endl;

return 0;

}The ternary operator uses short-circuit evaluation—it evaluates the condition, then evaluates only the chosen branch. The unchosen branch is never evaluated. This behavior matters when expressions have side effects like function calls that modify state. In the example, only increment or decrement executes, not both. This short-circuit behavior also enables safe operations like avoiding division by zero by putting the division in the branch that only executes when the divisor is non-zero.

Understanding when to use the ternary operator versus if-else statements requires considering readability and code intent:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Point {

private:

int x, y;

public:

Point(int xVal, int yVal) : x(xVal), y(yVal) {}

// Good use: simple value selection in return

int getQuadrant() const {

return (x >= 0) ? ((y >= 0) ? 1 : 4) : ((y >= 0) ? 2 : 3);

}

// Better as if-else for clarity

int getQuadrantClear() const {

if (x >= 0 && y >= 0) return 1;

if (x < 0 && y >= 0) return 2;

if (x < 0 && y < 0) return 3;

return 4;

}

// Good use: conditional formatting

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ") in quadrant "

<< getQuadrantClear() << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Point p1(3, 4);

Point p2(-2, 5);

Point p3(-1, -3);

Point p4(2, -1);

p1.display();

p2.display();

p3.display();

p4.display();

return 0;

}Use the ternary operator when selecting between two simple values based on a condition, particularly for initialization, return values, or building expressions. Use if-else statements when you have multiple conditions forming a chain, when executing actions with side effects rather than computing values, when the logic becomes complex enough that the ternary operator harms readability, or when you need to execute multiple statements for each branch. The key question is whether the ternary operator makes code more concise while maintaining clarity or whether it obscures meaning in pursuit of brevity.

Common mistakes with the ternary operator include creating deeply nested ternaries that are difficult to parse, forgetting that both branches must have compatible types, using ternary operators for complex logic better expressed with if-else, and forgetting about operator precedence when using ternary operators in larger expressions without parentheses.

Key Takeaways

The ternary operator provides a concise way to choose between two values based on a condition, using the syntax condition ? value_if_true : value_if_false. It creates an expression that produces a value rather than a statement that controls flow, enabling conditional initialization of const variables, conditional return values, and inline value selection in expressions. The ternary operator particularly shines when initializing const variables that depend on conditions.

The ternary operator uses short-circuit evaluation, evaluating only the chosen branch and not the other. This enables safe operations like avoiding division by zero and prevents unintended side effects from expressions in the unchosen branch. Both value branches must have compatible types that can convert to a common type, ensuring the ternary expression has a well-defined type for use in assignments and larger expressions.

Use the ternary operator for simple value selections where it enhances conciseness without sacrificing clarity. Avoid nested ternary operators that become difficult to read, particularly chains with multiple levels of nesting. For complex conditional logic, multiple branches, or operations with side effects, traditional if-else statements typically communicate intent more clearly. The choice between ternary operators and if-else statements should prioritize code readability while leveraging the ternary operator’s ability to treat conditional selection as expressions when appropriate.