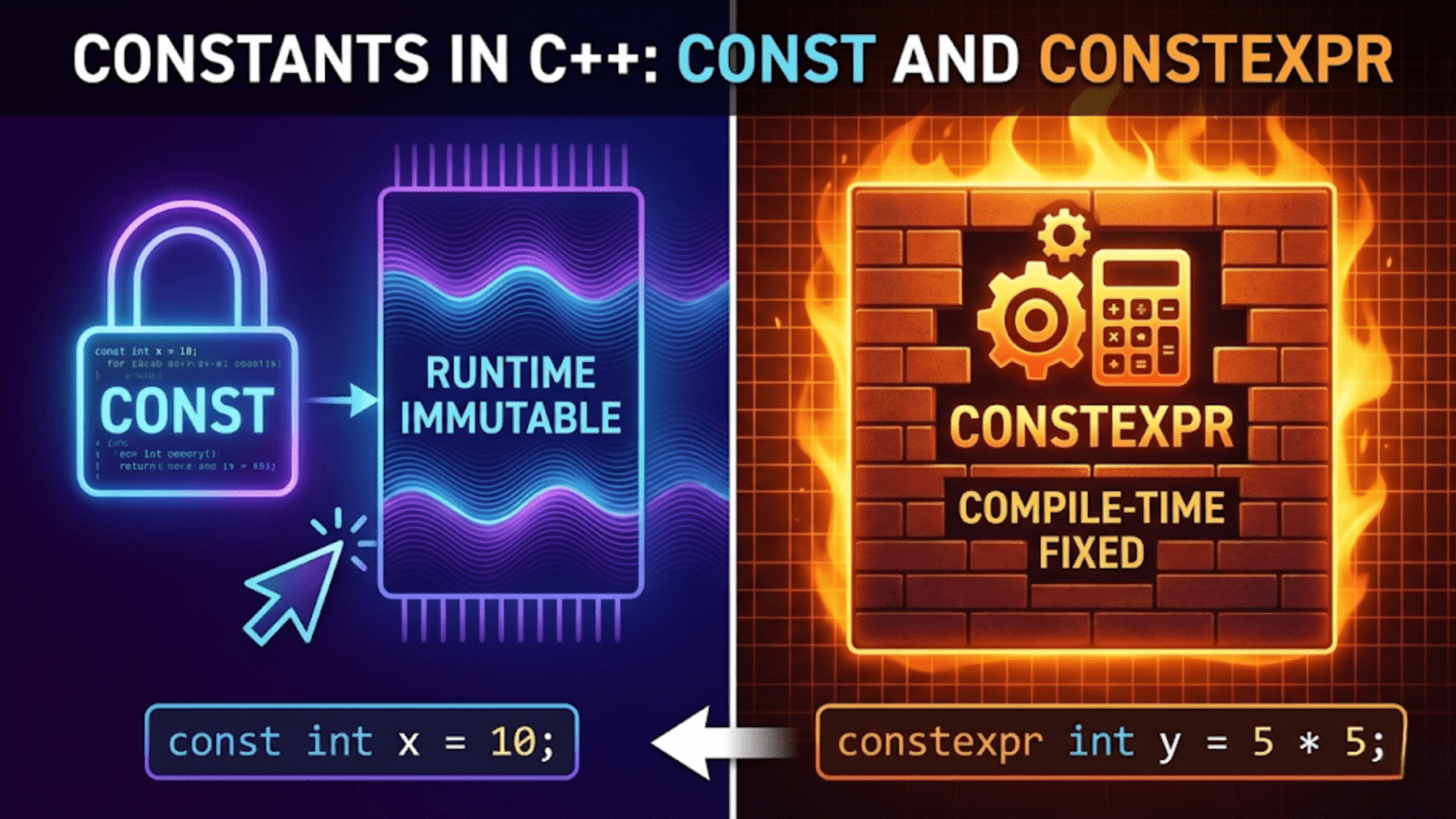

When you write programs, some values should never change after they’re set—mathematical constants like pi, configuration settings that should remain fixed throughout execution, or reference data that programs read but never modify. Allowing these values to be modified accidentally creates bugs that can be extremely difficult to track down because the symptoms appear far from where the unwanted modification occurred. C++ provides two primary mechanisms for creating constants—the const keyword that makes variables read-only after initialization, and the constexpr keyword that enables compile-time evaluation and guarantees. Understanding constants transforms you from someone who hopes values won’t change to someone who enlists the compiler’s help in enforcing immutability, catching errors at compile time rather than discovering them through runtime bugs.

Think of const like writing information in permanent marker instead of pencil. Once you write a value in permanent marker, you cannot erase or change it—it’s fixed. Similarly, const variables can be initialized but cannot be modified afterwards. The compiler enforces this immutability, producing errors if you attempt to change const values. This protection is invaluable because it documents your intentions (this value should not change) while the compiler verifies that your code follows those intentions. You can read const values as often as you like, but writing to them triggers compilation errors, preventing accidental modifications before the program ever runs.

The power of constants extends beyond simple immutability. Constants enable compiler optimizations because the compiler knows values won’t change, allowing more aggressive optimization strategies. They improve code readability by documenting which values are fixed versus variable. They enhance type safety by ensuring functions receive data they cannot accidentally modify. They enable compile-time computation through constexpr, performing calculations during compilation rather than runtime. Understanding const and constexpr deeply enables writing safer, more efficient code where immutability is enforced by the language itself rather than relying on programmer discipline.

Let me start by showing you basic const variables and how they prevent accidental modifications:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Const variable - must be initialized, cannot be changed

const int daysInWeek = 7;

const double pi = 3.14159265359;

std::cout << "Days in week: " << daysInWeek << std::endl;

std::cout << "Pi: " << pi << std::endl;

// Can read const variables as many times as needed

double circumference = 2 * pi * 5.0;

std::cout << "Circumference: " << circumference << std::endl;

// Cannot modify const variables

// daysInWeek = 8; // Compilation error!

// pi = 3.14; // Compilation error!

// Const variables must be initialized when declared

// const int value; // Compilation error - no initialization!

return 0;

}The const keyword declares variables whose values cannot be changed after initialization. You must initialize const variables when you declare them because there’s no opportunity to set their values later. Any attempt to modify a const variable produces a compilation error, making accidental modification impossible. This compile-time checking is far superior to runtime checking or relying on programmer discipline because errors are caught immediately during development rather than potentially going unnoticed until production.

Const works with any type, including user-defined types, making it broadly applicable throughout your programs:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Point {

private:

double x, y;

public:

Point(double xVal, double yVal) : x(xVal), y(yVal) {}

double getX() const { return x; } // Const member function

double getY() const { return y; }

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ")";

}

};

int main() {

// Const with various types

const int maxUsers = 100;

const double taxRate = 0.0825;

const std::string appName = "MyApplication";

const Point origin(0, 0);

// Can call const member functions on const objects

origin.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

std::cout << "X coordinate: " << origin.getX() << std::endl;

// Cannot modify const objects

// origin = Point(1, 1); // Compilation error!

return 0;

}Const works seamlessly with objects, but there’s an important interaction with member functions. Only member functions marked const can be called on const objects. This const correctness ensures that calling a function on a const object won’t modify it. Member functions should be marked const whenever they don’t modify the object’s state, enabling them to work with const objects.

Const pointers introduce additional complexity because you can have const pointers, pointers to const, or both:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int value1 = 10;

int value2 = 20;

// Pointer to const - cannot modify what it points to

const int* ptr1 = &value1;

std::cout << "Value through ptr1: " << *ptr1 << std::endl;

// *ptr1 = 15; // Error! Cannot modify through pointer to const

ptr1 = &value2; // OK - can change what pointer points to

// Const pointer - cannot change what it points to

int* const ptr2 = &value1;

*ptr2 = 15; // OK - can modify through pointer

std::cout << "Modified value: " << value1 << std::endl;

// ptr2 = &value2; // Error! Cannot change const pointer

// Const pointer to const - cannot change pointer or value

const int* const ptr3 = &value1;

// *ptr3 = 25; // Error! Cannot modify through pointer to const

// ptr3 = &value2; // Error! Cannot change const pointer

// Reading right to left helps understand declarations

// const int* ptr1 = "pointer to const int"

// int* const ptr2 = "const pointer to int"

// const int* const ptr3 = "const pointer to const int"

return 0;

}The position of const relative to the asterisk determines what’s constant. Reading the declaration right to left clarifies the meaning: “ptr1 is a pointer to const int” versus “ptr2 is a const pointer to int.” This distinction matters when passing pointers to functions—using pointers to const tells the function it cannot modify the pointed-to value, while const pointers prevent reassigning the pointer itself.

Const references are extremely common in function parameters because they enable passing large objects efficiently without allowing modification:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// Pass by const reference - efficient and safe

void displayString(const std::string& str) {

std::cout << "String: " << str << std::endl;

// str += " modified"; // Error! Cannot modify const reference

}

void processVector(const std::vector<int>& vec) {

std::cout << "Vector contains " << vec.size() << " elements" << std::endl;

for (const auto& element : vec) { // Const reference in range-based for

std::cout << element << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// vec.push_back(100); // Error! Cannot modify through const reference

}

class Rectangle {

private:

double width, height;

public:

Rectangle(double w, double h) : width(w), height(h) {}

double getArea() const {

return width * height;

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "Rectangle: " << width << " x " << height << std::endl;

}

};

// Pass by const reference avoids copying large objects

double calculateTotalArea(const std::vector<Rectangle>& rectangles) {

double total = 0;

for (const auto& rect : rectangles) {

total += rect.getArea(); // Can call const member functions

}

return total;

}

int main() {

std::string message = "Hello, const!";

displayString(message);

std::vector<int> numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

processVector(numbers);

std::vector<Rectangle> rects = {

Rectangle(3, 4),

Rectangle(5, 6),

Rectangle(2, 8)

};

std::cout << "Total area: " << calculateTotalArea(rects) << std::endl;

return 0;

}Passing by const reference combines efficiency (no copying) with safety (cannot modify). This pattern appears constantly in well-written C++ code because it provides optimal performance while making guarantees about whether functions modify their arguments. Functions that take const references document that they only read the data, not modify it, making code intent clearer.

The constexpr keyword introduces compile-time constants and functions, enabling computation during compilation rather than runtime:

#include <iostream>

// Constexpr variable - must be initialized with constant expression

constexpr int arraySize = 100;

constexpr double pi = 3.14159265359;

// Constexpr function - can be evaluated at compile time

constexpr int square(int x) {

return x * x;

}

constexpr int factorial(int n) {

return (n <= 1) ? 1 : n * factorial(n - 1);

}

constexpr double circleArea(double radius) {

return pi * radius * radius;

}

int main() {

// Compile-time constants

constexpr int compileTimeValue = square(5); // Computed at compile time

constexpr int fact5 = factorial(5);

// Can use constexpr values for array sizes

int array[compileTimeValue]; // Array of size 25

std::cout << "Square of 5: " << compileTimeValue << std::endl;

std::cout << "Factorial of 5: " << fact5 << std::endl;

// Constexpr functions can also be used at runtime

int runtimeValue = 10;

int result = square(runtimeValue); // Computed at runtime

std::cout << "Square of 10: " << result << std::endl;

// Compile-time circle area calculation

constexpr double area = circleArea(5.0);

std::cout << "Circle area: " << area << std::endl;

return 0;

}Constexpr variables must be initialized with constant expressions that can be evaluated at compile time. Constexpr functions can be evaluated at compile time if called with constant arguments, but they can also be called at runtime with non-constant arguments. The compiler decides whether to evaluate constexpr functions at compile time based on the context. When you assign a constexpr function result to a constexpr variable, the compiler guarantees compile-time evaluation.

Let me show you a comprehensive example demonstrating constants in a realistic application:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <cmath>

// Configuration constants

namespace Config {

constexpr int MAX_PLAYERS = 4;

constexpr int GRID_SIZE = 10;

constexpr double GRAVITY = 9.81;

const std::string GAME_TITLE = "Physics Puzzle";

constexpr double TIME_STEP = 0.016; // 60 FPS

}

// Compile-time calculations

namespace Physics {

constexpr double calculateFallDistance(double time) {

return 0.5 * Config::GRAVITY * time * time;

}

constexpr double calculateVelocity(double initialVelocity, double time) {

return initialVelocity + Config::GRAVITY * time;

}

constexpr int roundToInt(double value) {

return static_cast<int>(value + 0.5);

}

}

class GameObject {

private:

std::string name;

double x, y;

double velocityY;

public:

GameObject(const std::string& objName, double xPos, double yPos)

: name(objName), x(xPos), y(yPos), velocityY(0) {}

// Const member function - doesn't modify object

void display() const {

std::cout << name << " at (" << x << ", " << y << ")" << std::endl;

}

// Const member function

std::string getName() const {

return name;

}

// Non-const member function - modifies object

void update(double deltaTime) {

// Use const reference for deltaTime if it were complex

velocityY += Config::GRAVITY * deltaTime;

y += velocityY * deltaTime;

}

// Const member function using constexpr

double getDistanceFrom(double targetX, double targetY) const {

double dx = x - targetX;

double dy = y - targetY;

return std::sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

// Const getter

double getY() const { return y; }

};

class GameLevel {

private:

const int levelNumber; // Const member - never changes after construction

const std::string levelName;

std::vector<GameObject> objects;

public:

// Initialize const members in initializer list

GameLevel(int number, const std::string& name)

: levelNumber(number), levelName(name) {}

void addObject(const GameObject& obj) { // Pass by const reference

if (objects.size() < Config::MAX_PLAYERS) {

objects.push_back(obj);

}

}

// Const member function

void displayInfo() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Level " << levelNumber << ": "

<< levelName << " ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Objects: " << objects.size() << std::endl;

}

// Non-const member function

void updateAll(double deltaTime) {

for (auto& obj : objects) {

obj.update(deltaTime);

}

}

// Const member function

void displayAllObjects() const {

for (const auto& obj : objects) { // Const reference in loop

obj.display();

}

}

// Const getter

int getLevelNumber() const {

return levelNumber;

}

};

class PhysicsSimulator {

private:

static constexpr double DEFAULT_TIME_STEP = 0.016;

static constexpr int MAX_ITERATIONS = 1000;

public:

// Static constexpr function

static constexpr double predictFallDistance(double seconds) {

return Physics::calculateFallDistance(seconds);

}

// Static const member (defined outside class)

static const std::string ENGINE_NAME;

static void displayEngineInfo() {

std::cout << "\nPhysics Engine: " << ENGINE_NAME << std::endl;

std::cout << "Time step: " << DEFAULT_TIME_STEP << " seconds" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Gravity: " << Config::GRAVITY << " m/s²" << std::endl;

}

};

// Static const member definition

const std::string PhysicsSimulator::ENGINE_NAME = "SimplePhy v1.0";

int main() {

std::cout << "=== " << Config::GAME_TITLE << " ===" << std::endl;

// Use compile-time constant for array

constexpr int precomputedDistance = Physics::roundToInt(

Physics::calculateFallDistance(2.0)

);

std::cout << "Fall distance in 2 seconds: " << precomputedDistance

<< " meters (computed at compile time)" << std::endl;

PhysicsSimulator::displayEngineInfo();

// Create level with const members

GameLevel level1(1, "Sky Garden");

// Create objects

GameObject player("Player", 5.0, 10.0);

GameObject enemy("Enemy", 3.0, 8.0);

level1.addObject(player);

level1.addObject(enemy);

level1.displayInfo();

level1.displayAllObjects();

std::cout << "\nAfter physics update:" << std::endl;

level1.updateAll(Config::TIME_STEP);

level1.displayAllObjects();

// Demonstrate const correctness

const GameLevel constLevel(2, "Crystal Cave");

constLevel.displayInfo(); // Can call const member functions

// constLevel.updateAll(0.1); // Error! Cannot call non-const on const object

// Demonstrate const reference parameter

auto printLevelInfo = [](const GameLevel& lvl) {

std::cout << "Level number: " << lvl.getLevelNumber() << std::endl;

};

printLevelInfo(level1);

return 0;

}This comprehensive example demonstrates multiple uses of constants throughout a realistic application. Configuration constants use constexpr for compile-time values and const for runtime strings. Physics calculations use constexpr functions for compile-time computation when possible. The GameObject class uses const member functions for methods that don’t modify state. The GameLevel class has const members that are initialized once and never change. Function parameters use const references for efficiency and safety. The PhysicsSimulator uses static constexpr for compile-time constants and static const for runtime constants.

Understanding when to use const versus constexpr helps choose the right tool. Use const for values that shouldn’t change after initialization but might not be known at compile time. Use constexpr for values and functions that can be evaluated at compile time, enabling compile-time computation and optimization:

#include <iostream>

#include <ctime>

// Constexpr - value known at compile time

constexpr int BUFFER_SIZE = 1024;

constexpr double PI = 3.14159265359;

// Const - value might not be known until runtime

const int currentYear = 2025;

const time_t startTime = time(nullptr); // Runtime value

// Constexpr function - can be evaluated at compile time

constexpr int multiply(int a, int b) {

return a * b;

}

// Regular function - cannot be constexpr (uses runtime features)

int getUserInput() {

int value;

std::cin >> value;

return value;

}

int main() {

// Compile-time evaluation

constexpr int compileTime = multiply(10, 20);

// Runtime evaluation

int runtimeValue = getUserInput();

int result = multiply(runtimeValue, 5);

// Const can use runtime values

const int userSquare = runtimeValue * runtimeValue;

std::cout << "Compile-time result: " << compileTime << std::endl;

std::cout << "Runtime result: " << result << std::endl;

return 0;

}Constexpr provides stronger guarantees than const—constexpr variables are always const, but they’re guaranteed to be compile-time constants. Constexpr functions can be evaluated at compile time when called with constant expressions, potentially improving performance by moving computation from runtime to compile time.

Common mistakes with constants include forgetting to initialize const variables, attempting to modify const objects, calling non-const member functions on const objects, and confusing pointer-to-const with const-pointer. Another subtle error is assuming constexpr functions always evaluate at compile time—they only do so when called in contexts requiring constant expressions.

Key Takeaways

The const keyword makes variables immutable after initialization, preventing accidental modification through compile-time checking. Const variables must be initialized when declared and cannot be changed afterwards, with the compiler enforcing these rules. Const works with all types including user-defined classes and enables const member functions that can be called on const objects, supporting const correctness throughout programs.

Const pointers require understanding whether the pointer itself is const, what it points to is const, or both, with the position of const relative to the asterisk determining the meaning. Const references enable efficient passing of large objects to functions without copying while preventing modification, making them extremely common in function parameters. This combination of efficiency and safety represents best practice for parameter passing in modern C++.

The constexpr keyword enables compile-time constants and functions that can be evaluated during compilation. Constexpr provides stronger guarantees than const by ensuring values are compile-time constants when possible. Constexpr functions can be evaluated at compile time with constant arguments or at runtime with non-constant arguments, providing flexibility while enabling optimization. Understanding const and constexpr enables writing safer code where immutability is enforced by the compiler, improving correctness while enabling optimizations through guaranteed immutable and compile-time values.