The Essential Bridge Between Physical and Digital

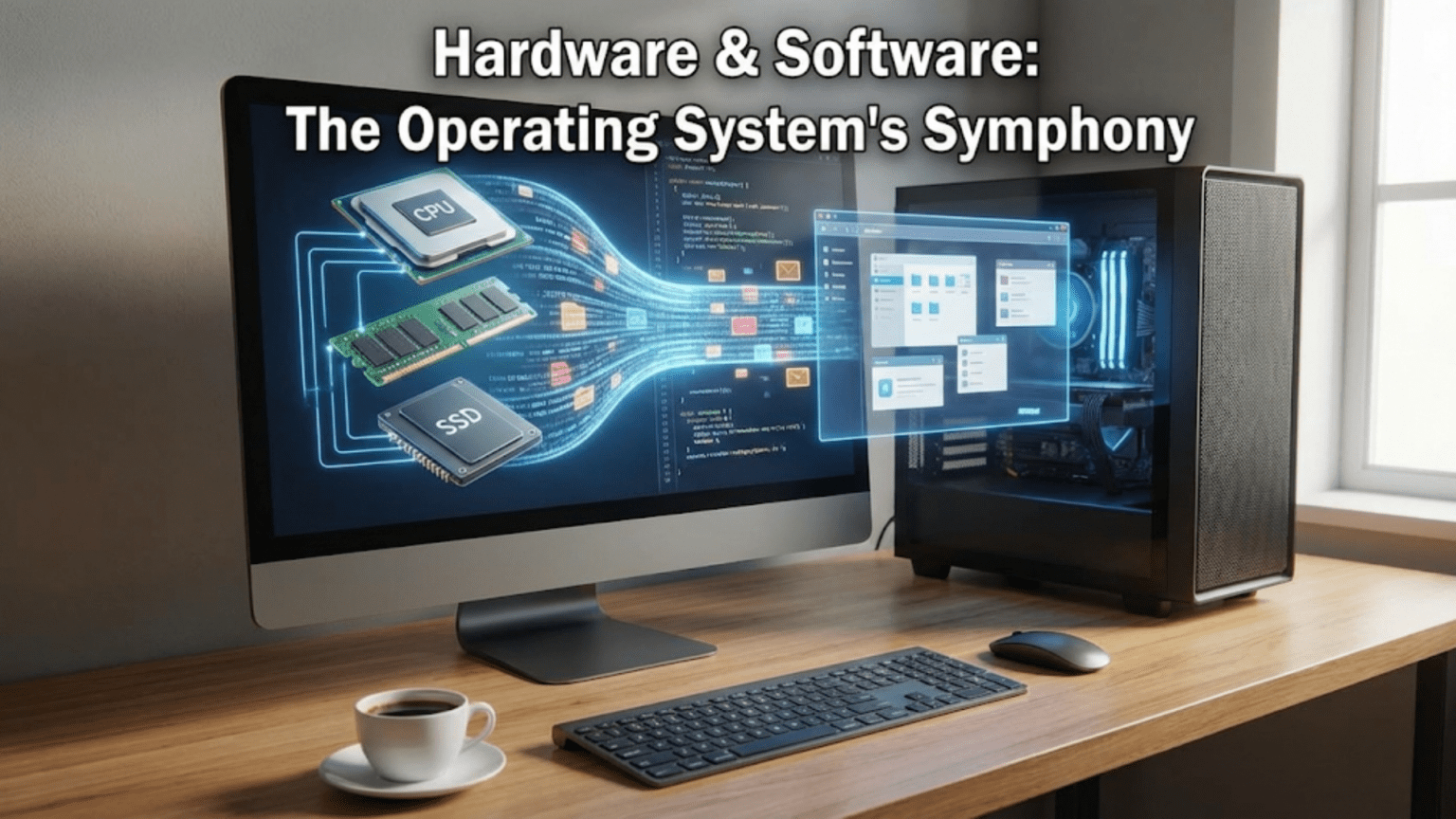

When you click your mouse, type on your keyboard, or watch a video on your screen, you’re witnessing a seamless partnership between hardware and software that’s so smooth you probably never think about it. The physical device—your mouse with its buttons and sensors—generates electrical signals that mean nothing by themselves. Software running on your processor interprets these signals, determines what they mean in the current context, and triggers appropriate responses. This constant translation between the physical world of electronic components and the logical world of software instructions happens through the operating system, which serves as the essential bridge connecting hardware capabilities with software needs.

This relationship between hardware and software represents one of computing’s most fundamental aspects, yet it’s largely invisible to users. Software developers write programs without knowing the exact details of the hardware they’ll run on. Hardware manufacturers create devices without knowing what specific software will use them. The operating system makes this independence possible by providing a standardization layer that allows hardware and software to evolve separately while still working together. Understanding this relationship reveals why operating systems are so critical, why drivers matter, and how computers achieve the remarkable compatibility that lets countless different programs run on equally countless hardware configurations.

The interaction between hardware and software isn’t a simple one-way street where software commands and hardware obeys. It’s a sophisticated dialogue involving multiple layers of abstraction, translation, and coordination. Hardware has capabilities and constraints that software must respect. Software has requirements and expectations that hardware must fulfill. The operating system mediates this relationship, translating between the abstract operations that programmers work with and the concrete electrical signals that hardware responds to. This mediation enables the computing flexibility we take for granted—the same program can print to hundreds of different printer models, display on countless monitor types, and run on processors from various manufacturers, all without modification.

Hardware Components and Their Software Interfaces

Understanding the relationship between hardware and software starts with recognizing the major hardware components and how software interacts with each.

The processor (CPU) represents the hardware component that actually executes software instructions. Every program consists of sequences of processor instructions—add these numbers, compare these values, move this data to that location. The processor retrieves these instructions from memory, decodes what they mean, executes them, and moves to the next instruction. This cycle repeats billions of times per second. Software consists entirely of these instructions, written in a form the processor understands. The operating system schedules which program’s instructions execute when, manages transitions between programs, and ensures all programs follow rules about what they can and cannot do.

Memory (RAM) stores both program instructions and the data they manipulate. From the processor’s perspective, memory is a vast array of numbered locations, each holding a small amount of data. Software uses memory addresses to specify where data is stored or should be retrieved. The operating system manages memory allocation, determining which programs get which memory regions, preventing programs from accessing memory they shouldn’t, and implementing virtual memory that makes limited physical RAM appear larger than it actually is. The hardware provides the physical storage; the software provides the organizational structure and access policies.

Storage devices like hard drives and SSDs persistently store data that survives when the computer powers off. These devices have complex internal mechanisms—spinning platters and moving read heads in hard drives, flash memory cells in SSDs—but they present relatively simple interfaces to software: read data from this location, write data to that location. The operating system implements file systems that organize raw storage into the hierarchical folders and files that users and programs work with, translating between filename-based requests and the physical sectors where data actually resides.

Display hardware presents visual information generated by software. Modern displays are sophisticated devices with their own processors and memory, but from software’s perspective, they’re essentially large arrays of pixels that can be individually colored. Graphics drivers translate high-level drawing commands—render this text, display this image, draw this shape—into the specific pixel manipulations required to produce the desired visual output. The operating system coordinates display access, ensuring multiple programs can share the screen without interfering with each other.

Input devices like keyboards, mice, and touchscreens capture user actions and convert them into data that software can process. A keyboard press generates a scan code identifying which key was pressed. A mouse movement generates coordinate changes. The operating system receives these hardware events, interprets them in context—which window is active, what mode the system is in—and routes them to appropriate programs. This routing and interpretation turns raw hardware events into meaningful application input.

Network adapters enable communication with other computers. These devices handle the electrical or radio transmission of data packets, but software controls what data to send and how to interpret received data. The operating system implements network protocols, breaking data into packets, managing transmission, handling errors, and reassembling received packets into usable data. Network software operates at multiple layers, from physical signal handling through high-level application protocols, with the operating system managing the entire stack.

The Hardware Abstraction Layer

The hardware abstraction layer (HAL) represents one of the operating system’s most important functions: hiding hardware complexity behind simplified, standardized interfaces that software can use without knowing hardware details.

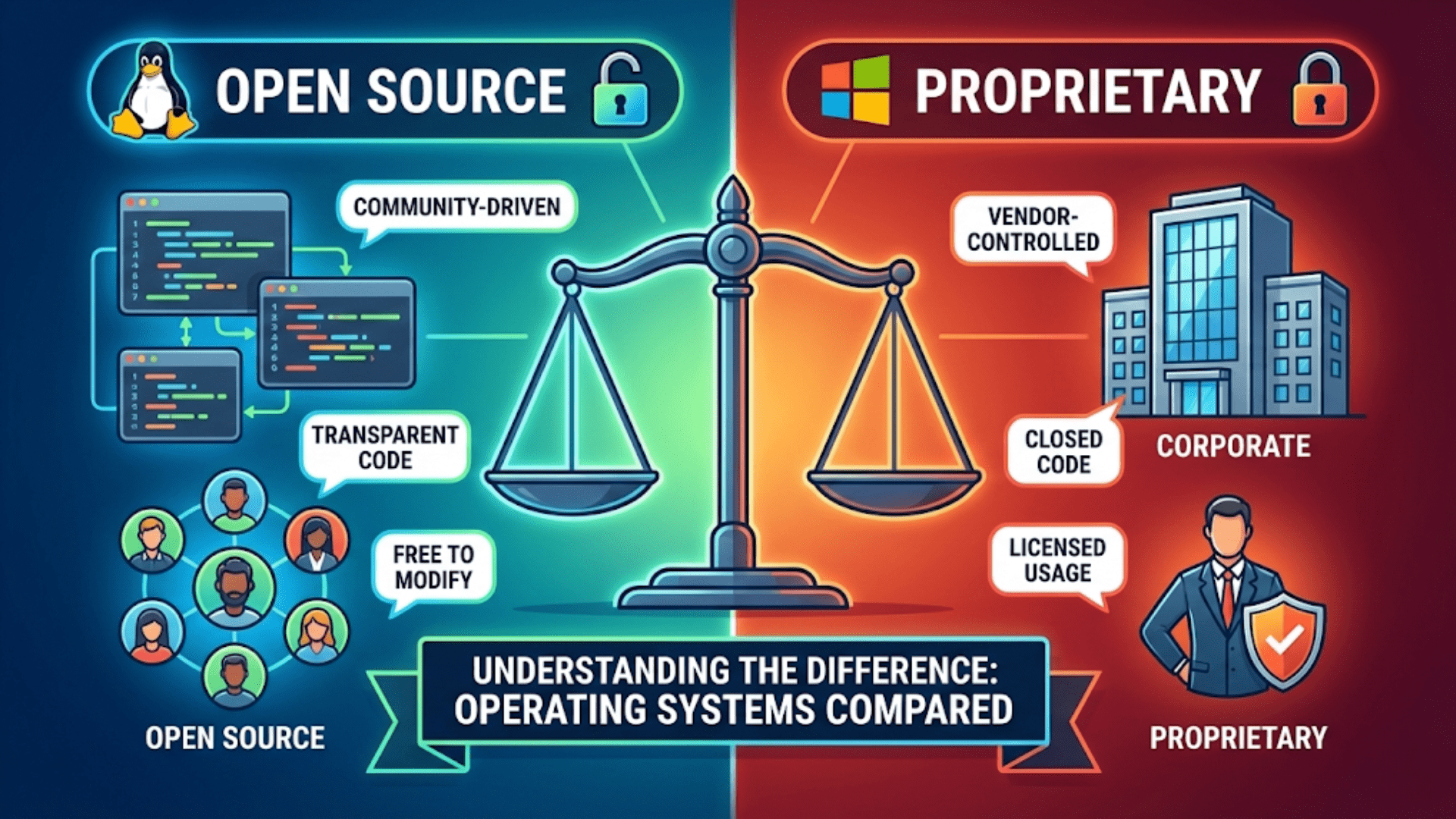

Different hardware devices provide similar functionality but with different specific interfaces. Consider storage: SATA drives, NVMe SSDs, USB flash drives, and SD cards all store data, but each uses different communication protocols and commands. Without abstraction, every program that needs storage would require separate code for each device type, making software development impractical. The HAL solves this by providing a common storage interface—programs request “read this file” or “write this data”—and the HAL translates these generic requests into device-specific commands.

This abstraction benefits both software developers and hardware manufacturers. Developers write code once against the abstract interface rather than repeatedly for each device. Hardware manufacturers can innovate and create new devices with different internal implementations, knowing that if they provide appropriate drivers, existing software will work without modification. This separation allows hardware and software to evolve independently, a crucial factor in computing’s rapid advancement.

The abstraction isn’t perfect or complete—some hardware capabilities are unique and cannot be fully abstracted. High-performance applications sometimes need hardware-specific features, requiring code that works only with particular devices. Gaming graphics, for example, often uses vendor-specific extensions that provide capabilities beyond the standard abstraction. The operating system allows this direct access when necessary while maintaining abstraction for common operations, balancing portability with performance.

Different abstraction layers exist at various levels. The HAL itself abstracts hardware from the kernel. Device class interfaces abstract specific devices from drivers. Programming APIs abstract system services from applications. Each layer adds flexibility and portability while introducing some overhead. The operating system carefully designs these layers to provide needed abstraction without excessive performance cost.

Device Drivers: The Hardware-Software Translators

Device drivers represent specialized software components that implement the actual hardware-specific details that the hardware abstraction layer hides. Understanding drivers reveals how operating systems achieve hardware compatibility.

Each driver is essentially a translator that speaks two languages: the standardized interface the operating system expects, and the specific protocol that particular hardware understands. When the operating system wants to perform an operation—say, reading data from a disk—it calls standardized functions in the storage driver. The driver translates this generic request into the exact sequence of commands that particular disk controller requires, sends those commands to the hardware, waits for completion, and returns results in the standardized format the operating system expects.

Driver complexity varies dramatically based on device sophistication. A keyboard driver might be relatively simple—scan codes arrive from the keyboard controller, and the driver translates them to key events. A graphics driver can contain hundreds of thousands of lines of code implementing complex rendering pipelines, memory management, and optimization for specific GPU architectures. This complexity reflects both the hardware’s capabilities and the performance requirements that make efficient hardware use essential.

Drivers operate in privileged kernel mode with direct hardware access, which gives them power but also makes them dangerous. A buggy driver can crash the entire system because kernel-mode code has no restrictions on what it can do. This is why driver quality matters tremendously and why operating systems implement mechanisms like driver signing to prevent unauthorized or malicious drivers from loading. The privileged nature of drivers also explains why adding new hardware sometimes requires administrator access—installing drivers modifies the kernel.

Some operating systems support user-mode drivers for certain device categories, running drivers with restricted privileges like regular applications. User-mode drivers can’t crash the kernel if they fail, improving system stability. However, the indirection required for user-mode drivers to access hardware creates performance overhead, making this approach suitable only for devices where latency isn’t critical. Printers often use user-mode drivers successfully, while high-performance network adapters and graphics cards still require kernel-mode drivers.

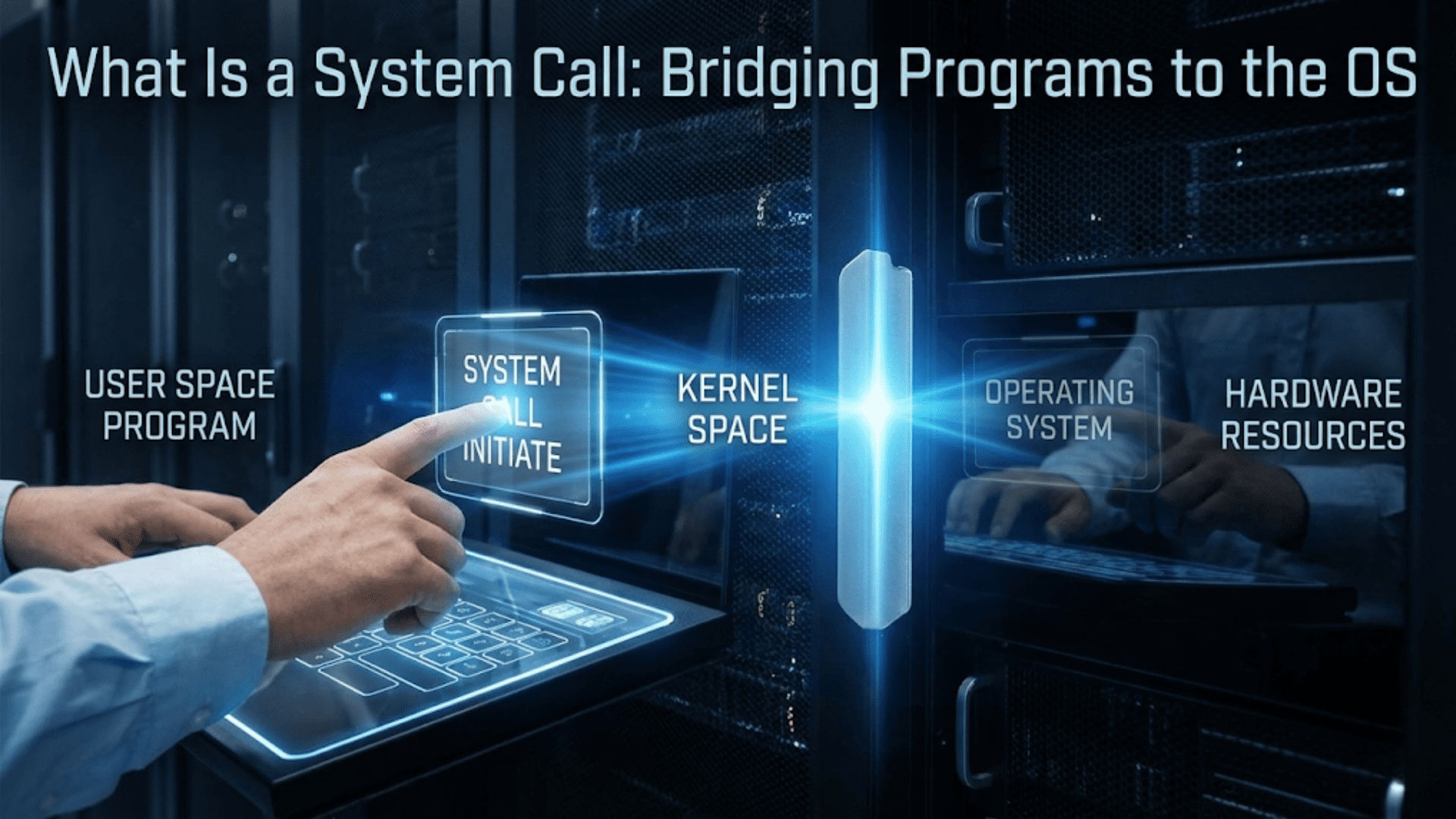

System Calls: How Applications Request Hardware Services

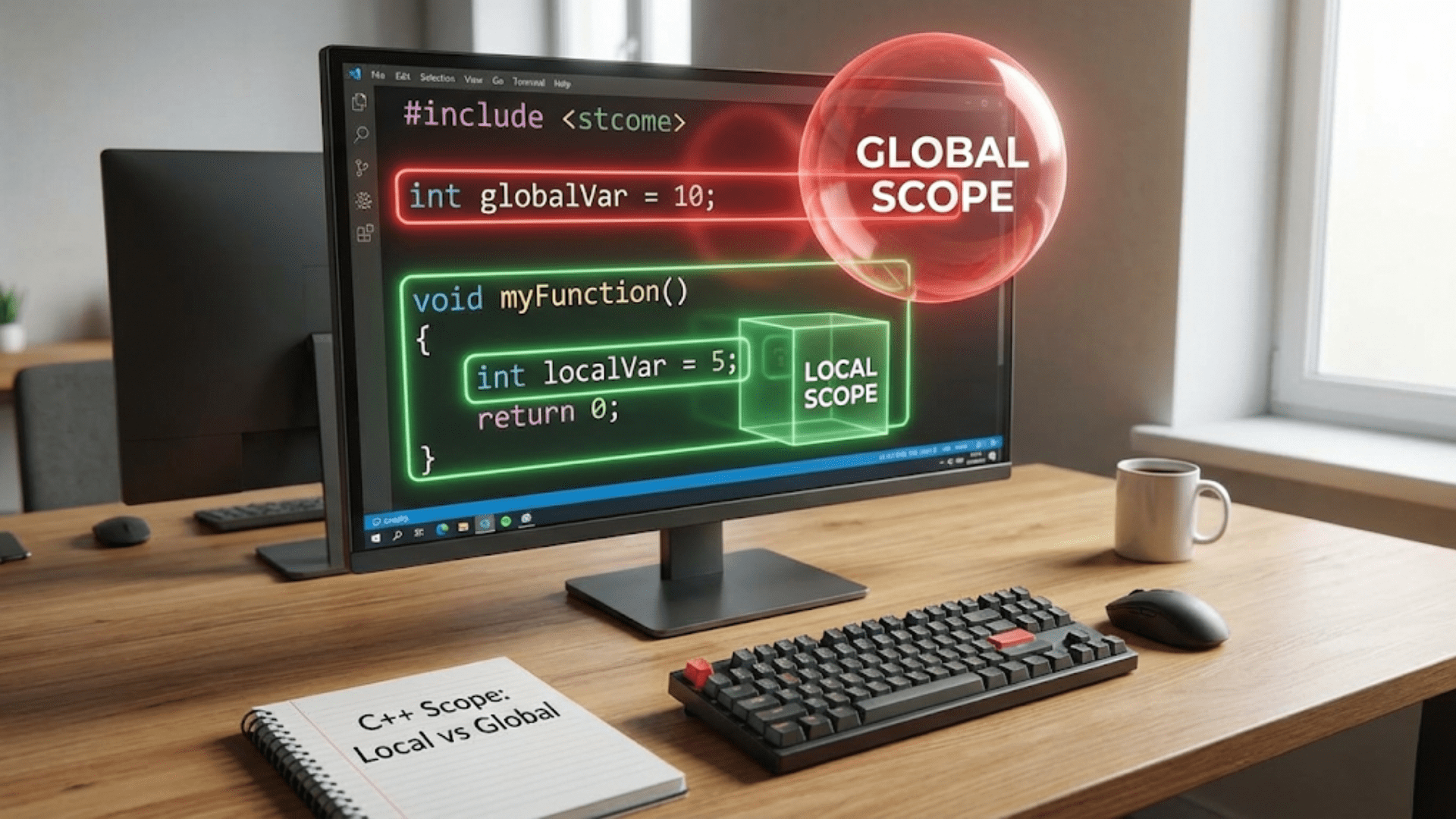

Applications don’t directly access hardware—doing so would compromise security and stability. Instead, they make system calls that request the operating system to perform hardware operations on their behalf. Understanding system calls reveals how software safely uses hardware resources.

A system call is a controlled transition from user mode (where applications run with restricted privileges) to kernel mode (where the operating system runs with full hardware access). The application executes a special processor instruction that triggers this transition, passing parameters that specify what operation is requested. The processor switches to kernel mode, transfers control to the operating system’s system call handler, which performs the requested operation and returns results to the application. The processor then switches back to user mode, and the application continues with the results.

This controlled access maintains system security and stability. Applications cannot directly manipulate hardware, preventing malicious or buggy programs from damaging the system or interfering with other programs. The operating system validates every system call, ensuring the requesting program has permission to perform the operation and that parameters are valid. This validation layer prevents applications from accessing files they shouldn’t read, using memory they don’t own, or performing operations that would compromise system integrity.

System calls cover all hardware interactions that applications need. File I/O system calls read and write files. Network system calls send and receive data. Process management system calls create new programs or terminate running ones. Memory management system calls allocate or free memory. Display system calls render graphics. This comprehensive API allows applications to accomplish anything while maintaining the security boundary between user and kernel space.

The overhead of system calls is carefully managed because they’re frequent—even simple programs make thousands of system calls. The transition between user and kernel mode takes time, and the kernel must perform validation and operation setup. Operating systems optimize common system calls, provide mechanisms to batch multiple operations, and offer memory-mapped I/O that reduces system call frequency for certain operations. Despite optimization, excessive system calls can impact performance, encouraging efficient programming practices.

Interrupts: Hardware’s Way of Getting Software’s Attention

While system calls allow software to request hardware services, interrupts provide the opposite direction of communication—hardware notifying software that something needs attention.

An interrupt is a signal from hardware indicating an event has occurred that requires immediate handling. When a key is pressed, the keyboard controller generates an interrupt. When a network packet arrives, the network adapter interrupts. When a disk completes a read operation, the disk controller interrupts. These signals cause the processor to immediately suspend its current activity, save its state, and jump to an interrupt handler—a function in the operating system designed to respond to that specific interrupt.

The interrupt mechanism enables efficient I/O handling. Without interrupts, the operating system would need to constantly poll devices—repeatedly check if events have occurred—wasting processor time on devices that aren’t ready. With interrupts, the processor executes useful work until devices signal they need attention, making much more efficient use of computing resources. This interrupt-driven model is fundamental to responsive, efficient computing.

Interrupt handlers must execute quickly because they block other operations while running. They typically perform only essential immediate processing—acknowledge the interrupt, retrieve urgent data, perhaps schedule additional processing—then return quickly so normal execution can resume. Less time-critical processing happens later through deferred procedure calls or bottom halves, which execute outside the immediate interrupt context. This split approach balances responsiveness with thoroughness.

Interrupt priority levels allow managing multiple simultaneous interrupt sources. High-priority interrupts can interrupt low-priority handlers, ensuring critical events receive immediate attention even when other interrupts are being serviced. The operating system configures interrupt priorities based on device criticality—timing-sensitive devices like audio get higher priority than less critical devices like keyboards. This priority system ensures the most important events get timely handling.

DMA: Direct Memory Access Without CPU Involvement

Direct Memory Access (DMA) represents another important hardware-software interaction mechanism that improves efficiency by allowing devices to transfer data to and from memory without constant CPU involvement.

Traditional I/O requires the processor to move every byte of data between devices and memory. When reading from disk, the processor reads each data byte from the disk controller and writes it to memory. This constant processor involvement wastes CPU time on simple data movement rather than useful computation. DMA solves this by allowing devices to directly access memory, moving data independently while the processor works on other tasks.

The operating system sets up DMA transfers by programming the DMA controller with source address, destination address, and data length. Once configured, the device and DMA controller handle the entire transfer without processor involvement. When complete, the device generates an interrupt notifying the operating system that the transfer finished. The processor was free to execute other code throughout the transfer, only needing to handle setup and completion notification.

DMA dramatically improves performance for bulk data transfers like disk I/O, network packet reception, or audio streaming. These operations involve moving large amounts of data where the processor would otherwise spend significant time on simple copying. DMA offloads this work to specialized hardware, freeing the processor for computation that actually requires it. Modern systems use DMA extensively, with most I/O operations employing it automatically without applications needing awareness.

Memory consistency concerns arise with DMA because devices can modify memory that the processor has cached. Modern systems use cache coherency protocols and explicit cache management to ensure the processor sees current data written by DMA and devices see current data written by the processor. The operating system and drivers handle these details, maintaining consistency without application involvement.

Memory-Mapped I/O: Hardware Registers as Memory

Memory-mapped I/O represents another important hardware-software interface mechanism where device registers appear as memory addresses, allowing software to control hardware through normal memory operations.

Instead of special I/O instructions, memory-mapped devices occupy addresses in the processor’s memory space. Writing to these addresses actually writes to device control registers, sending commands to hardware. Reading from these addresses retrieves device status or data. From the programmer’s perspective, controlling hardware becomes as simple as reading and writing memory, though those operations have side effects in hardware rather than just changing stored values.

This approach simplifies driver development because normal pointer operations work to access device registers. It also allows standard memory access instructions to control hardware, making device access efficient and straightforward. Most modern systems use memory-mapped I/O extensively, with different address ranges mapped to different devices. The operating system manages these mappings, ensuring device memory appears at appropriate addresses and preventing user programs from directly accessing device registers.

Memory-mapped I/O also enables sharing data between devices and software through shared memory regions. Graphics cards use this extensively—the frame buffer (image to be displayed) resides in memory that both the GPU and CPU can access. Software writes pixel data to this shared region, and the graphics hardware reads it for display. This arrangement enables efficient graphics without constantly transferring data between separate memory spaces.

The Boot Process: Software Taking Control of Hardware

The boot process demonstrates the hardware-software relationship beautifully, showing how software progressively takes control of bare hardware.

When you press the power button, hardware initializes first. The power supply stabilizes voltages, the processor resets to a known state, and the processor begins executing instructions from firmware (BIOS or UEFI) stored in read-only memory on the motherboard. At this moment, no operating system exists—just hardware and the minimal firmware needed to test and initialize it.

The firmware tests essential hardware through the Power-On Self-Test (POST), initializes components to basic operational states, and locates boot media containing an operating system. This initialization bridges from pure hardware to the point where software can begin loading. The firmware knows how to read storage devices and network boot servers, providing the minimal capabilities needed to load more sophisticated software.

The bootloader, loaded by firmware from storage, continues the progression toward a full operating system. It knows how to access file systems, locate the operating system kernel, load it into memory, and transfer control to it. The bootloader is more sophisticated than firmware but still relatively simple compared to the operating system itself. It exists solely to launch the OS.

Finally, the operating system kernel loads and takes full control. It initializes its data structures, loads device drivers, starts system services, and eventually launches user applications. At this point, the hardware-software relationship reaches its normal operating state—hardware providing capabilities, software using them through operating system abstraction layers.

Hardware-Software Co-Design and Evolution

The relationship between hardware and software isn’t static—it evolves as each influences the other’s development.

Software requirements drive hardware innovation. When applications need specific capabilities—say, faster graphics rendering—hardware manufacturers develop components providing those capabilities. Graphics processors evolved from simple frame buffers to sophisticated programmable processors largely because games and visual applications demanded it. Each generation of software pushes hardware capabilities, and hardware advances enable new software possibilities.

Hardware capabilities enable new software paradigms. Touch screens enabled mobile interfaces fundamentally different from mouse-and-keyboard interactions. Accelerometers and gyroscopes enabled motion-based gaming. Neural processing units enable on-device machine learning. Hardware innovation creates opportunities that software exploits, sometimes in ways hardware designers didn’t anticipate. This co-evolution drives computing forward through continuous feedback between hardware possibilities and software needs.

Standardization efforts balance innovation with compatibility. Industry standards define interfaces that both hardware and software implement, ensuring interoperability. USB, PCI Express, SATA, WiFi, Bluetooth—these standards allow hardware from any manufacturer to work with any operating system. Standards sometimes lag innovation, with cutting-edge hardware requiring proprietary interfaces initially and later standardizing as technology matures.

Backward compatibility maintains relationships across generations. Operating systems continue supporting older hardware through legacy drivers and interface support. Hardware continues supporting older software through compatibility modes and standardized interfaces. This backward compatibility creates stability—your old printer works with new operating systems, and old software runs on new hardware—though it also creates complexity as systems maintain old interfaces alongside new ones.

Virtualization: Software Simulating Hardware

Virtualization represents an interesting twist on the hardware-software relationship—software pretending to be hardware, creating virtual machines that look like physical computers.

A hypervisor is software that creates and manages virtual machines, presenting each with virtual hardware—virtual CPU, virtual memory, virtual storage, virtual network adapter. Guest operating systems running in virtual machines see this virtual hardware and interact with it exactly as they would physical hardware, unaware they’re virtualized. The hypervisor translates virtual hardware operations to actual hardware operations, allowing multiple guest operating systems to share physical hardware safely.

This software simulation of hardware enables powerful capabilities. Multiple operating systems can run simultaneously on one physical computer, each isolated in its own virtual machine. Test environments can be created, used, and destroyed without affecting physical hardware. Legacy systems can run on modern hardware through virtualization even when native support no longer exists. Cloud computing fundamentally depends on virtualization to efficiently share massive physical infrastructure among many users.

Hardware-assisted virtualization improves performance by adding processor features specifically supporting virtualization. Modern CPUs include instructions and capabilities that allow hypervisors to execute guest code directly on the processor rather than translating every instruction, dramatically improving performance. Hardware virtualization extensions like Intel VT-x and AMD-V transformed virtualization from relatively slow emulation to nearly native performance.

The Future: New Hardware-Software Relationships

The hardware-software relationship continues evolving as new technologies emerge and computing paradigms shift.

Specialized hardware accelerators for specific workloads are becoming common. Neural processing units accelerate machine learning, graphics processors increasingly handle general computation, custom encryption processors accelerate security operations. These specialized components challenge the traditional general-purpose computing model where software runs on CPUs, requiring operating systems to manage diverse processing elements and route work to appropriate hardware.

Quantum computing represents an entirely new hardware-software relationship. Quantum computers operate on fundamentally different principles than classical computers, requiring completely new programming models and operating system concepts. While quantum computers remain specialized and experimental, they demonstrate that the hardware-software relationship isn’t fixed—radically different hardware requires radically different software approaches.

Edge computing and IoT devices create new constraints on the hardware-software relationship. These devices often have minimal resources—tiny amounts of memory, slow processors, no persistent storage—requiring scaled-down operating systems and carefully optimized software. The relationship between hardware and software on a microcontroller in a sensor is quite different from a desktop computer, though fundamental principles of abstraction and interface design still apply.

Neuromorphic computing mimics biological neural networks in hardware, potentially enabling new computing paradigms fundamentally different from today’s von Neumann architecture. These systems blur traditional distinctions between hardware and software, with configuration and programming happening through training rather than explicit instruction sequences. While still largely research, neuromorphic computing suggests future computing might work quite differently than today’s hardware-software models.

Understanding Improves Troubleshooting and Optimization

Understanding the hardware-software relationship makes you more effective at troubleshooting problems and optimizing performance.

When hardware problems occur—devices not recognized, operations failing, performance issues—understanding the relationship helps diagnosis. Is it a driver problem? Hardware failure? Software configuration? The abstraction layers mean problems can occur at multiple levels, and understanding where each component’s responsibility lies guides investigation.

Performance optimization benefits from understanding hardware capabilities and limitations. Software can be written to efficiently use hardware features, avoid operations that hardware handles poorly, and structure work to align with hardware characteristics. Drivers can be updated to better expose hardware capabilities. Hardware can be upgraded where it’s the bottleneck. Understanding the complete stack from application through operating system to hardware enables informed optimization decisions.

The relationship between hardware and software, mediated by the operating system, represents one of computing’s foundational concepts. Every action you perform on a computer involves this relationship—software expressing what you want to accomplish, the operating system translating those desires into hardware-specific operations, and hardware executing those operations and reporting results back up the stack. Understanding this relationship demystifies computing, reveals why systems behave as they do, and provides foundation for deeper technical knowledge. The next time you click a mouse or press a key, appreciate the remarkable engineering that takes your simple physical action and transforms it into meaningful computational results through the sophisticated hardware-software partnership that the operating system orchestrates.