The perceptron is the simplest type of artificial neural network, consisting of a single neuron that takes multiple inputs, applies weights and a bias, sums them, and passes the result through an activation function to produce a binary output. Invented by Frank Rosenblatt in 1958, the perceptron can learn to classify linearly separable patterns using a simple learning rule that adjusts weights based on prediction errors. While limited to linear decision boundaries, the perceptron laid the foundation for modern deep learning and introduced key concepts still used today.

Introduction: The Birth of Neural Networks

In 1958, Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, unveiled the Mark I Perceptron—a machine that could learn to recognize simple patterns. The New York Times proclaimed it “the embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence.” While that prediction was overly optimistic, Rosenblatt had created something profound: the first practical artificial neural network.

The perceptron is the simplest possible neural network—a single artificial neuron that learns from examples. Despite its simplicity, the perceptron introduced fundamental concepts that underpin all modern deep learning: weighted inputs, learnable parameters, threshold-based decisions, and iterative learning from errors. Every complex neural network, from GPT to AlphaGo, builds upon principles first demonstrated in this elementary model.

Understanding the perceptron is essential for anyone learning neural networks. It’s simple enough to understand completely—you can implement one in a few lines of code and trace every calculation by hand—yet sophisticated enough to demonstrate how learning happens in neural systems. The perceptron shows how machines can learn decision boundaries from data, foreshadowing the pattern recognition capabilities of modern AI.

This comprehensive guide explores the perceptron in depth. You’ll learn exactly how it works, its mathematical foundations, the learning algorithm that adjusts its weights, what problems it can and cannot solve, its historical significance, and how it evolved into modern neural networks. With clear explanations, visual examples, and hands-on implementations, you’ll develop a complete understanding of this foundational model.

What is a Perceptron? The Basic Concept

A perceptron is a single-layer neural network—the simplest possible architecture that can learn.

The Structure

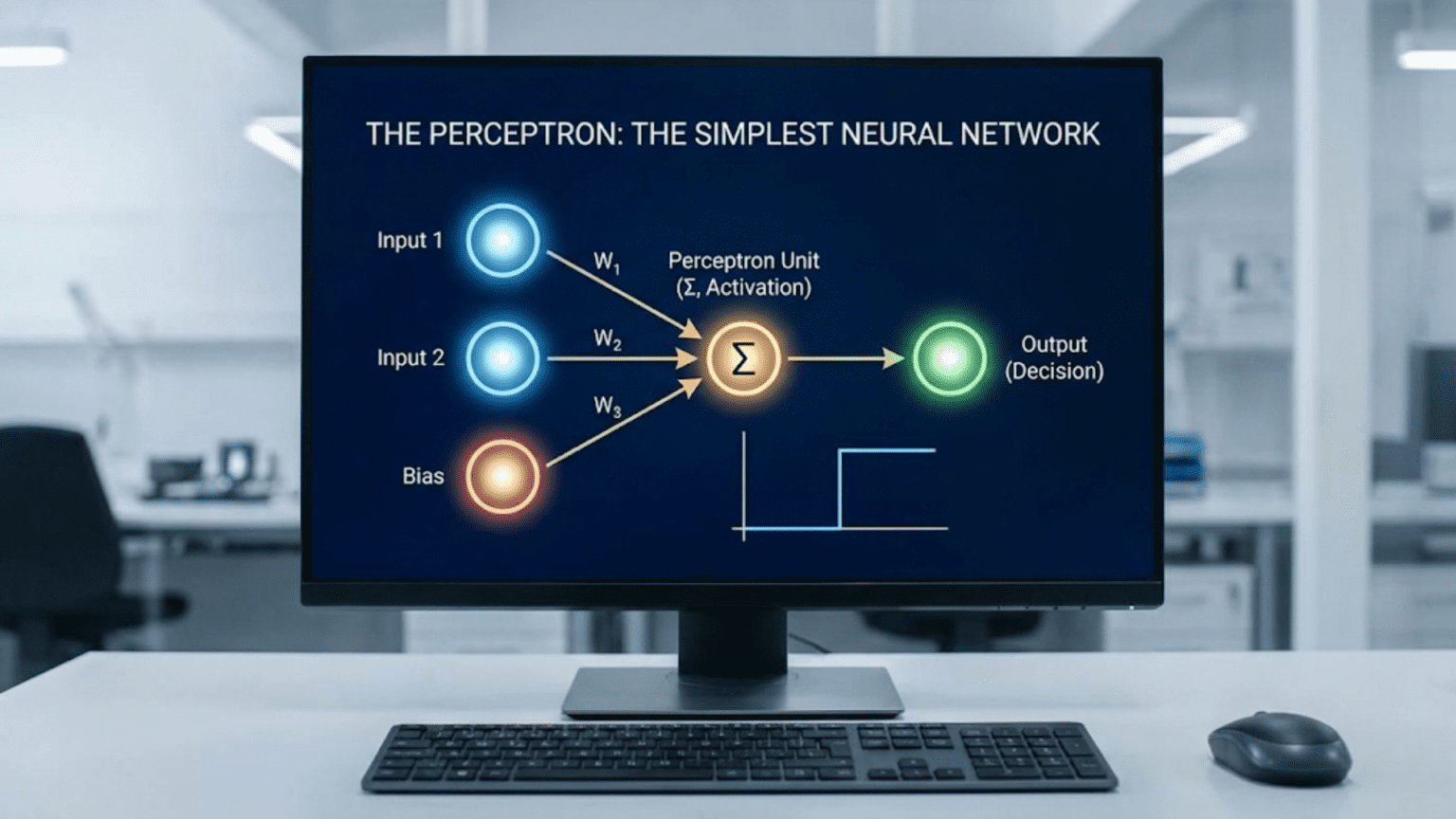

Components:

1. Input Layer (x₁, x₂, …, xₙ):

- Multiple input values

- Features describing the example

- Numerical values

2. Weights (w₁, w₂, …, wₙ):

- One weight per input

- Determines input importance

- Learned during training

- Can be positive or negative

3. Bias (b):

- Additional learnable parameter

- Shifts the decision boundary

- Like an intercept in linear equations

4. Summation Function:

- Weighted sum of inputs plus bias

- z = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + … + wₙxₙ + b

5. Activation Function:

- Applies threshold

- Produces final output

- Typically step function (0 or 1)

6. Output (ŷ):

- Binary prediction

- Usually 0 or 1 (or -1 and +1)

- Single value

Visual Representation

Inputs Weights Summation Activation Output

x₁ ─────────────→ w₁ ─┐

│

x₂ ─────────────→ w₂ ─┤

├─→ Σ(wᵢxᵢ + b) ──→ f(z) ────→ ŷ

x₃ ─────────────→ w₃ ─┤

│

b ──────────────→ 1 ──┘Mathematical Formula

Step 1: Weighted Sum

z = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + ... + wₙxₙ + b

= Σ(wᵢxᵢ) + bStep 2: Activation (Step Function)

ŷ = f(z) = {1 if z ≥ 0

{0 if z < 0Or sometimes:

ŷ = {+1 if z ≥ 0

{-1 if z < 0Simple Example

Problem: Classify if a student passes (1) or fails (0) based on study hours and sleep hours

Input Features:

- x₁ = study hours (0-10)

- x₂ = sleep hours (0-10)

Perceptron Parameters (learned):

- w₁ = 0.5 (weight for study hours)

- w₂ = 0.3 (weight for sleep hours)

- b = -3 (bias)

Prediction for New Student:

Student: study=6 hours, sleep=8 hours

z = (0.5 × 6) + (0.3 × 8) + (-3)

z = 3 + 2.4 - 3

z = 2.4

ŷ = f(2.4) = 1 (since 2.4 ≥ 0)

Prediction: PassThe Perceptron Learning Algorithm

How does the perceptron learn the right weights? Through a simple but powerful algorithm.

The Learning Process

Goal: Adjust weights so predictions match actual labels

Principle: Update weights based on errors

Algorithm:

1. Initialize weights randomly (or to zero)

2. For each training example (x, y):

a. Make prediction: ŷ = f(Σwᵢxᵢ + b)

b. Calculate error: error = y - ŷ

c. Update each weight: wᵢ = wᵢ + η × error × xᵢ

d. Update bias: b = b + η × error

3. Repeat until convergence (or max iterations)Where:

- η (eta) = learning rate (controls step size)

- error = actual – predicted

- If correct (error=0): weights unchanged

- If wrong (error≠0): weights adjusted

Learning Rule Intuition

Case 1: Correct Prediction

Actual: 1, Predicted: 1

Error: 1 - 1 = 0

Update: wᵢ = wᵢ + η × 0 × xᵢ = wᵢ (no change)

Weights stay the same—already working!Case 2: False Negative (should be 1, predicted 0)

Actual: 1, Predicted: 0

Error: 1 - 0 = 1

Update: wᵢ = wᵢ + η × 1 × xᵢ

If xᵢ > 0: weight increases (strengthens positive contribution)

If xᵢ < 0: weight decreases (reduces negative contribution)

Result: Next time, more likely to predict 1Case 3: False Positive (should be 0, predicted 1)

Actual: 0, Predicted: 1

Error: 0 - 1 = -1

Update: wᵢ = wᵢ + η × (-1) × xᵢ

If xᵢ > 0: weight decreases (reduces positive contribution)

If xᵢ < 0: weight increases (adds negative contribution)

Result: Next time, more likely to predict 0Step-by-Step Example

Problem: Learn AND gate (binary logic)

Training Data:

x₁ x₂ y (AND)

0 0 0

0 1 0

1 0 0

1 1 1Initialization:

w₁ = 0, w₂ = 0, b = 0

η = 0.1 (learning rate)Iteration 1, Example 1: x₁=0, x₂=0, y=0

z = (0×0) + (0×0) + 0 = 0

ŷ = f(0) = 1 (step function: 1 if z≥0)

error = 0 - 1 = -1

w₁ = 0 + 0.1×(-1)×0 = 0

w₂ = 0 + 0.1×(-1)×0 = 0

b = 0 + 0.1×(-1) = -0.1

New: w₁=0, w₂=0, b=-0.1Iteration 1, Example 2: x₁=0, x₂=1, y=0

z = (0×0) + (0×1) + (-0.1) = -0.1

ŷ = f(-0.1) = 0

error = 0 - 0 = 0

No update (correct prediction)

Weights: w₁=0, w₂=0, b=-0.1Iteration 1, Example 3: x₁=1, x₂=0, y=0

z = (0×1) + (0×0) + (-0.1) = -0.1

ŷ = f(-0.1) = 0

error = 0 - 0 = 0

No update

Weights: w₁=0, w₂=0, b=-0.1Iteration 1, Example 4: x₁=1, x₂=1, y=1

z = (0×1) + (0×1) + (-0.1) = -0.1

ŷ = f(-0.1) = 0

error = 1 - 0 = 1

w₁ = 0 + 0.1×1×1 = 0.1

w₂ = 0 + 0.1×1×1 = 0.1

b = -0.1 + 0.1×1 = 0

New: w₁=0.1, w₂=0.1, b=0Continue iterations until all predictions correct…

Final Learned Weights (after convergence):

w₁ ≈ 0.5, w₂ ≈ 0.5, b ≈ -0.7Verify:

(0,0): z = 0.5×0 + 0.5×0 - 0.7 = -0.7 → ŷ=0 ✓

(0,1): z = 0.5×0 + 0.5×1 - 0.7 = -0.2 → ŷ=0 ✓

(1,0): z = 0.5×1 + 0.5×0 - 0.7 = -0.2 → ŷ=0 ✓

(1,1): z = 0.5×1 + 0.5×1 - 0.7 = 0.3 → ŷ=1 ✓Perfect! The perceptron learned the AND function.

Geometric Interpretation: Decision Boundaries

The perceptron learns a linear decision boundary that separates classes.

Two-Dimensional Case

Perceptron Equation: w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + b = 0

This is the equation of a line!

Decision Boundary: Line where z = 0

- Points where w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + b = 0

- Separates positive and negative predictions

Classification:

- Above line (z > 0): Class 1

- Below line (z < 0): Class 0

- On line (z = 0): Boundary

Example Visualization (AND gate):

x₂

│

1 │ ○ ● (1,1) → 1

│

│ ○ ○

0 │_______________x₁

0 1

Decision boundary: 0.5x₁ + 0.5x₂ - 0.7 = 0

Simplifies to: x₁ + x₂ = 1.4

○ = Class 0 (below line)

● = Class 1 (above line)What Perceptron Learns

During Training:

- Starts with random line (random weights)

- Adjusts line to separate classes

- Rotates and shifts boundary

- Stops when all points correctly classified

Weights Control:

- w₁, w₂: Slope/orientation of line

- b: Position (shifts line)

Learning = Finding Right Line:

- Line that separates positive and negative examples

- Minimizes classification errors

Higher Dimensions

3D (Three Inputs):

- Decision boundary = Plane

- w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + w₃x₃ + b = 0

n Dimensions:

- Decision boundary = Hyperplane

- w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + … + wₙxₙ + b = 0

Principle: Perceptron always learns linear decision boundary

The Perceptron Convergence Theorem

Powerful Guarantee: If data is linearly separable, the perceptron will find a solution in finite steps.

Linearly Separable

Definition: Two classes can be perfectly separated by a straight line (or hyperplane)

Linearly Separable Examples:

- AND gate: Can draw line separating 0s and 1s

- OR gate: Can separate classes

- Simple binary classification with clear separation

NOT Linearly Separable:

- XOR gate: No line can separate (we’ll see why this matters)

- Concentric circles

- Interleaved patterns

Convergence Theorem (Rosenblatt, 1958):

IF data is linearly separable

THEN perceptron will converge to a solution in finite steps

Steps bounded by: (R/γ)²

Where:

- R = maximum distance of any point from origin

- γ = margin (minimum distance from points to optimal hyperplane)Practical Implication:

- Linearly separable → guaranteed convergence

- Not linearly separable → will never converge, oscillates forever

Limitations of the Perceptron

Despite its elegance, the perceptron has fundamental limitations.

Limitation 1: Only Linear Boundaries

Problem: Can only learn linear decision boundaries

Consequence: Cannot solve non-linearly separable problems

Famous Example: XOR Problem

XOR Truth Table:

x₁ x₂ y (XOR)

0 0 0

0 1 1

1 0 1

1 1 0Visualization:

x₂

│

1 │ 1 0

│

│ 0 1

0 │___________x₁

0 1Problem: No straight line separates 1s from 0s!

- Any line that puts (0,1) and (1,0) on one side also captures (0,0) or (1,1)

- Fundamentally impossible for single perceptron

Historical Impact:

- Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert’s 1969 book “Perceptrons” highlighted this limitation

- Caused “AI Winter”—funding and interest in neural networks dried up

- Not overcome until multi-layer networks in 1980s

Limitation 2: Binary Output Only

Problem: Single perceptron produces only binary output

Consequence: Cannot solve:

- Multi-class classification (more than 2 classes)

- Regression (continuous values)

- Probability estimates

Workarounds:

- Multi-class: One perceptron per class

- Continuous: Different activation function (but then not classic perceptron)

Limitation 3: No Hidden Representations

Problem: No intermediate layers to learn features

Consequence:

- Must work with given features

- Cannot learn feature combinations

- Cannot discover abstract representations

Example:

Given: Raw pixel values

Can't learn: "This is an edge" or "this is a curve"

Limited to: Direct pixel-to-class mappingLimitation 4: Sensitive to Outliers

Problem: Perceptron tries to classify all points correctly

Consequence: Single outlier can significantly affect decision boundary

No Margin Maximization: Unlike SVM, doesn’t maximize separation margin

Limitation 5: No Probabilistic Output

Problem: Output is hard 0 or 1

Consequence: No confidence estimates

- Can’t say “90% confident this is class 1”

- Just binary prediction

Modern Solution: Use sigmoid activation (becomes logistic regression)

From Perceptron to Modern Neural Networks

The perceptron evolved into sophisticated neural networks.

Evolution 1: Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

Key Innovation: Add hidden layers

Architecture:

Input → Hidden Layer 1 → Hidden Layer 2 → Output

Solves: XOR and other non-linear problems

- Hidden layers create non-linear decision boundaries

- Can approximate any continuous function (universal approximation theorem)

XOR Solution with 2-Layer Network:

Input Layer (2) → Hidden Layer (2) → Output Layer (1)

Hidden layer learns:

- Neuron 1: Detects x₁ OR x₂

- Neuron 2: Detects x₁ AND x₂

Output combines:

- Output = (x₁ OR x₂) AND NOT(x₁ AND x₂)

- This is XOR!Evolution 2: Different Activation Functions

Beyond Step Function:

Sigmoid: σ(z) = 1/(1 + e^(-z))

- Smooth, differentiable

- Outputs probabilities (0 to 1)

- Enables gradient-based learning

Tanh: tanh(z) = (e^z – e^(-z))/(e^z + e^(-z))

- Similar to sigmoid

- Outputs -1 to 1

- Often works better than sigmoid

ReLU: f(z) = max(0, z)

- Modern standard for deep networks

- Faster training

- Reduces vanishing gradient problem

Impact: Smooth activations enable backpropagation

Evolution 3: Backpropagation

Beyond Perceptron Learning Rule:

Problem: Perceptron rule doesn’t work for multi-layer networks

- Can’t directly compute error for hidden layers

Solution: Backpropagation (1986)

- Compute gradient of error with respect to weights

- Propagate error backward through network

- Update all weights using gradient descent

Impact: Enabled training deep networks

Evolution 4: Continuous Outputs

Regression:

- Use linear activation (no threshold)

- Predict continuous values

Multi-class Classification:

- Multiple output neurons

- Softmax activation

- Probability distribution over classes

Evolution 5: Specialized Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs):

- Specialized for images

- Convolutional layers detect local patterns

- Built from perceptron-like units

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs):

- Feedback connections

- Process sequences

- Memory of past inputs

Transformers:

- Attention mechanisms

- Parallel processing

- Modern NLP standard

Foundation: All build on perceptron’s core idea

Implementing a Perceptron

Let’s build a perceptron from scratch to solidify understanding.

Python Implementation

import numpy as np

class Perceptron:

def __init__(self, learning_rate=0.1, n_iterations=100):

self.lr = learning_rate

self.n_iterations = n_iterations

self.weights = None

self.bias = None

def fit(self, X, y):

"""Train the perceptron"""

n_samples, n_features = X.shape

# Initialize weights and bias to zero

self.weights = np.zeros(n_features)

self.bias = 0

# Convert y to -1 and 1 (if not already)

y_ = np.where(y <= 0, -1, 1)

# Training loop

for _ in range(self.n_iterations):

for idx, x_i in enumerate(X):

# Prediction

linear_output = np.dot(x_i, self.weights) + self.bias

y_predicted = np.where(linear_output >= 0, 1, -1)

# Update if wrong

if y_[idx] * y_predicted <= 0: # Misclassified

update = self.lr * y_[idx]

self.weights += update * x_i

self.bias += update

def predict(self, X):

"""Make predictions"""

linear_output = np.dot(X, self.weights) + self.bias

return np.where(linear_output >= 0, 1, -1)

# Example: AND gate

X = np.array([[0, 0], [0, 1], [1, 0], [1, 1]])

y = np.array([0, 0, 0, 1])

perceptron = Perceptron(learning_rate=0.1, n_iterations=10)

perceptron.fit(X, y)

print("Learned weights:", perceptron.weights)

print("Learned bias:", perceptron.bias)

print("Predictions:", perceptron.predict(X))Using Scikit-learn

from sklearn.linear_model import Perceptron

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Generate linearly separable data

X, y = make_classification(n_samples=100, n_features=2, n_redundant=0,

n_informative=2, n_clusters_per_class=1)

# Split data

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

# Train perceptron

perceptron = Perceptron(max_iter=100, eta0=0.1, random_state=42)

perceptron.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Evaluate

accuracy = perceptron.score(X_test, y_test)

print(f"Accuracy: {accuracy:.2f}")

# Weights and bias

print("Weights:", perceptron.coef_)

print("Bias:", perceptron.intercept_)Historical Significance and Legacy

The perceptron’s impact extends far beyond its technical capabilities.

1958: The Mark I Perceptron

Frank Rosenblatt’s Achievement:

- First hardware implementation

- 400 photocells as “retina”

- Learned to distinguish simple shapes

- Demonstrated machine learning in action

Media Hype:

- New York Times coverage

- Predictions of thinking machines

- Public excitement about AI

Reality:

- Could solve simple problems

- Demonstrated learning from examples

- Showed promise of neural approaches

1969: “AI Winter”

Minsky and Papert’s Book:

- Mathematically proved perceptron limitations

- XOR problem unsolvable by single perceptron

- Highlighted what perceptrons cannot do

Impact:

- Funding dried up

- Research interest declined

- Neural networks largely abandoned

Unfair Critique:

- Multi-layer networks could solve XOR

- But training methods not yet developed

- Focus on limitations rather than potential

1980s: Renaissance

Backpropagation Discovery (1986):

- Rumelhart, Hinton, Williams

- Training method for multi-layer networks

- Overcame perceptron limitations

Renewed Interest:

- Multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) powerful

- Could learn non-linear boundaries

- Universal function approximators

Modern Era: Foundation of Deep Learning

Legacy:

- Every neuron in deep networks is perceptron-like

- Core concepts persist:

- Weighted sums

- Learnable parameters

- Threshold/activation

- Error-driven learning

Evolution:

- Deeper networks (100+ layers)

- Better activations (ReLU vs step)

- Advanced optimization (Adam vs perceptron rule)

- Specialized architectures (CNN, Transformer)

But Fundamentally: Same basic building block

Practical Applications of Perceptrons

Where perceptrons (and linear classifiers) still useful:

Use Case 1: Simple Binary Classification

When Appropriate:

- Linearly separable data

- Need interpretability

- Fast training required

- Limited data

Examples:

- Spam vs. not spam (with good features)

- Sentiment: positive vs. negative

- Pass vs. fail (with clear criteria)

Use Case 2: Online Learning

Advantage: Can update one example at a time

Applications:

- Streaming data

- Adaptive systems

- Real-time learning

Example: Email spam filter that learns from user feedback

Use Case 3: Ensemble Component

Use: Perceptrons as weak learners in ensembles

Methods:

- Boosting: Combine multiple perceptrons

- Voting: Ensemble of perceptron variants

Use Case 4: Feature Selection

Use: Perceptron weights indicate feature importance

Process:

- Train perceptron

- Examine weights

- Large weights → important features

- Small weights → unimportant features

Use Case 5: Teaching Tool

Perfect For:

- Learning neural network basics

- Understanding gradient-free learning

- Visualizing decision boundaries

- Implementing from scratch

Comparison: Perceptron vs. Modern Methods

| Aspect | Perceptron | Multi-Layer NN | Logistic Regression | SVM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Single neuron | Multiple layers | Single neuron | Kernel methods |

| Decision Boundary | Linear | Non-linear possible | Linear | Non-linear with kernels |

| Activation | Step function | ReLU, sigmoid, etc. | Sigmoid | N/A (different approach) |

| Output | Binary (0/1) | Continuous/multi-class | Probability (0-1) | Binary/continuous |

| Learning | Perceptron rule | Backpropagation | Gradient descent | Quadratic programming |

| Can Solve XOR | No | Yes | No | Yes (with kernel) |

| Convergence | Guaranteed if separable | Not guaranteed | Guaranteed | Guaranteed |

| Interpretability | High | Low | High | Medium |

| Speed | Very fast | Slower | Fast | Medium |

| Best For | Simple, linearly separable | Complex patterns | Probabilistic classification | Max-margin classification |

Conclusion: Simple Yet Profound

The perceptron stands as one of the most elegant ideas in machine learning. A single artificial neuron that learns from examples, adjusting weights based on errors until it correctly classifies linearly separable patterns. Simple to understand, simple to implement, yet sophisticated enough to demonstrate the core principles of neural learning.

Its limitations—inability to solve XOR, restriction to linear boundaries, binary outputs—ultimately proved as instructive as its capabilities. These limitations motivated the development of multi-layer networks, backpropagation, and eventually deep learning. The perceptron’s failure to solve XOR launched research that eventually enabled networks to master far more complex tasks.

Understanding the perceptron provides essential foundation for neural networks:

Core concepts introduced:

- Weighted inputs representing importance

- Learnable parameters adjusted by experience

- Threshold-based activation

- Error-driven learning

- Geometric interpretation as decision boundaries

Limitations that drove progress:

- Need for hidden layers (multi-layer networks)

- Need for smooth activations (sigmoid, ReLU)

- Need for better learning algorithms (backpropagation)

- Need for non-linear boundaries (deep learning)

Every modern deep neural network—whether classifying images, translating languages, or playing games—consists of perceptron-like units connected in sophisticated architectures, trained with advanced algorithms, but fundamentally built on the same principles Rosenblatt demonstrated in 1958.

The perceptron’s journey from breakthrough to limitation to foundation teaches an important lesson about AI progress: sometimes the most valuable contributions aren’t perfect solutions but rather elegant ideas that reveal both what’s possible and what’s needed next. The perceptron showed that machines could learn from examples, demonstrated the power and limits of single-layer networks, and established principles that remain relevant sixty years later.

As you continue learning about neural networks, remember that every complex architecture you encounter builds on this simple foundation: artificial neurons receiving weighted inputs, computing sums, passing through activations, and learning from errors. Master the perceptron, and you’ve mastered the fundamental building block of all neural networks.