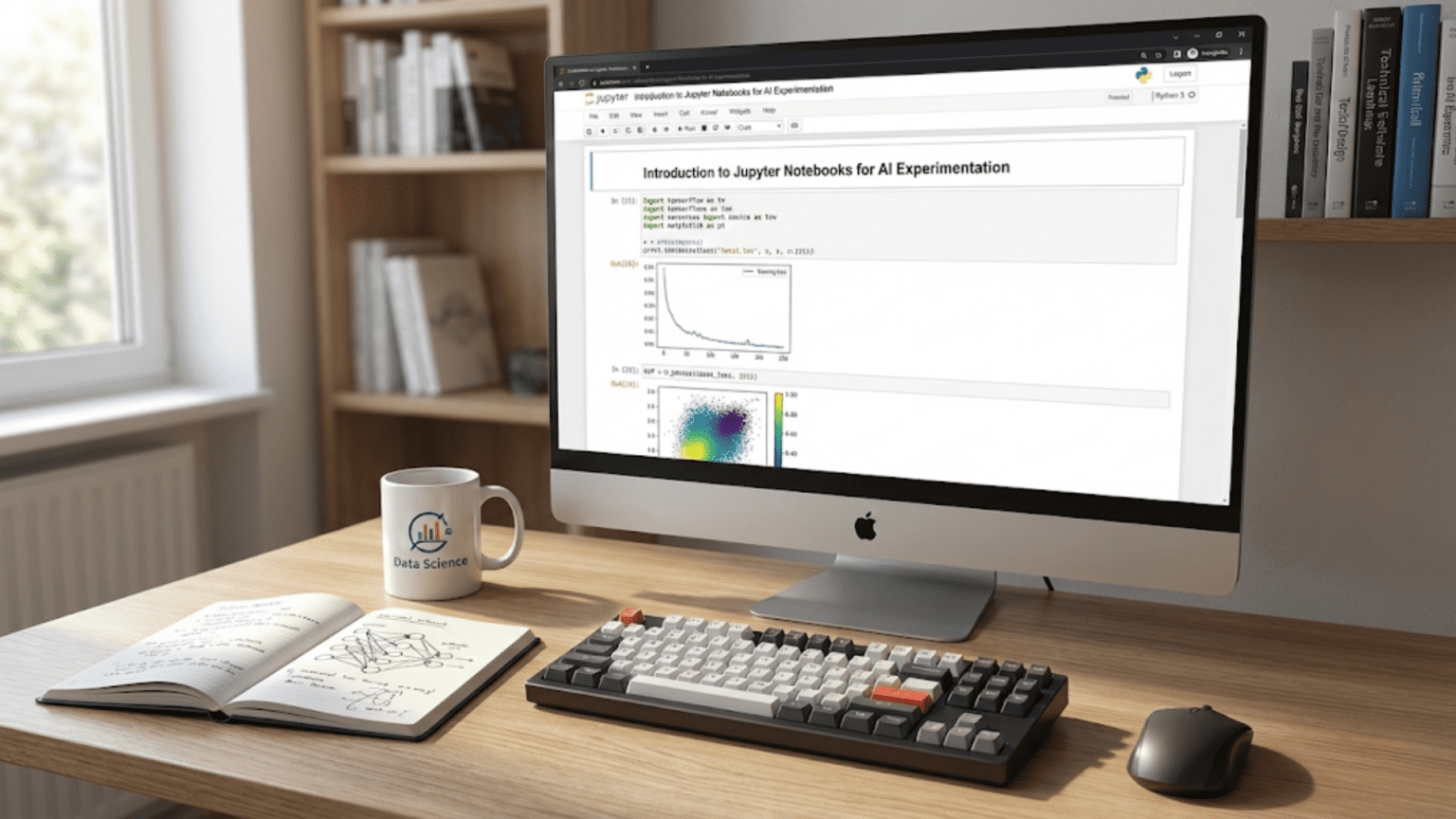

Introduction: Why Jupyter Notebooks Revolutionized Data Science

Traditional programming involves writing code in text editors, saving files, and running entire scripts from the command line. This workflow works well for building applications but creates friction for data science and machine learning. When exploring data, you need to see results immediately. When training models, you want to examine intermediate outputs. When presenting findings, you need code, visualizations, and explanations together. Jupyter Notebooks solve these problems by creating an interactive, iterative environment specifically designed for data analysis and machine learning.

The name “Jupyter” comes from three programming languages: Julia, Python, and R, though Jupyter now supports over 40 languages. The “notebook” metaphor is deliberate—like a laboratory notebook where scientists record experiments, observations, and conclusions, a Jupyter Notebook combines executable code, results, visualizations, and narrative text in a single document. This integration transforms how data scientists work.

Consider a typical machine learning workflow. You load data and want to see its structure immediately. You create a visualization and need to adjust parameters until it looks right. You train a model and want to examine predictions on sample data. You discover an issue and need to modify earlier code without rerunning everything. Jupyter Notebooks make all of this natural. You execute code in small chunks called cells, see results instantly, modify specific parts without restarting, and document your thinking alongside your code.

This interactive approach accelerates experimentation dramatically. Instead of waiting for entire scripts to run, you iterate quickly on small pieces. Instead of printing debugging information to files, you examine objects directly. Instead of creating separate documentation, you embed explanations with code. This efficiency explains why Jupyter Notebooks have become the standard environment for data science, machine learning research, education, and analysis.

This comprehensive guide will transform you into a proficient Jupyter Notebook user. We’ll start by understanding what Jupyter Notebooks are and how they differ from traditional programming. We’ll explore the interface and master cell-based execution. We’ll learn to combine code, visualizations, and markdown text effectively. We’ll discover keyboard shortcuts and features that accelerate your work. We’ll explore best practices for organizing notebooks, managing state, and collaborating with others. Throughout, we’ll focus on practical machine learning scenarios, ensuring you learn not just the mechanics but the workflow patterns that make you productive.

Understanding Jupyter Notebooks: The Core Concepts

Before diving into using Jupyter Notebooks, you need to understand what they are fundamentally and how they work differently from traditional Python development. This conceptual understanding prevents confusion and helps you leverage Jupyter’s strengths while avoiding its pitfalls.

What is a Jupyter Notebook?

A Jupyter Notebook is an interactive document that contains three types of content: code cells containing executable Python (or other language) code, markdown cells containing formatted text, equations, and images, and output cells displaying the results of code execution including text, tables, plots, and interactive widgets. These elements combine to create a computational narrative—a story told through code and data.

The notebook is both a document and an execution environment. When you run code in a cell, Python executes it and displays results immediately below. The Python interpreter (called the kernel) stays running in the background, maintaining all variables, functions, and imports you’ve created. This persistence means you can define a variable in one cell and use it in cells executed later, enabling the step-by-step workflow essential for data exploration.

The Client-Server Architecture

Jupyter uses a client-server architecture that might seem complex initially but provides important capabilities. The Jupyter server runs on your computer (or a remote machine), managing kernels and notebook files. The client is a web browser interface where you view and edit notebooks. This separation means you can run computationally intensive code on a powerful server while viewing results in a lightweight browser interface.

When you type code in the browser and press Shift+Enter, the browser sends that code to the server. The server passes it to the Python kernel for execution. The kernel runs the code, captures outputs, and sends them back to the server. The server forwards results to the browser for display. This happens so quickly it feels instant, but understanding the architecture explains certain behaviors like what happens when the kernel crashes or how you can connect to remote servers.

Cells: The Fundamental Unit

Cells are the building blocks of notebooks. Each cell is an independent execution unit that can be run, modified, and rerun individually. This granularity is Jupyter’s primary advantage over traditional scripts. Instead of running an entire file, you execute specific cells, allowing you to work on one part of your analysis without affecting others.

Code cells contain Python code that executes when run. The cell can contain a single line or many lines, and the last expression’s value is automatically displayed (unless you suppress it with a semicolon). Markdown cells contain formatted text using markdown syntax, supporting headers, lists, bold/italic text, links, images, and LaTeX equations. Raw cells contain unformatted text that isn’t executed or rendered, useful for including code examples that shouldn’t run.

The Kernel: Your Python Interpreter

The kernel is the computational engine that executes your code. When you open a notebook, Jupyter starts a Python kernel (or kernel for another language). This kernel maintains state—all variables, imports, and function definitions persist between cell executions. This persistence enables interactive workflows but requires awareness: if you define a variable in one cell, delete that cell, and later reference the variable, it still exists in memory even though the definition isn’t visible in the notebook.

Understanding kernel state is crucial. You can run cells in any order, not just top-to-bottom. This flexibility enables experimentation but can create confusion if you’re not careful about execution order. The kernel can be restarted, clearing all variables and requiring re-execution of cells to rebuild state. Regular kernel restarts help verify your notebook runs from a clean state.

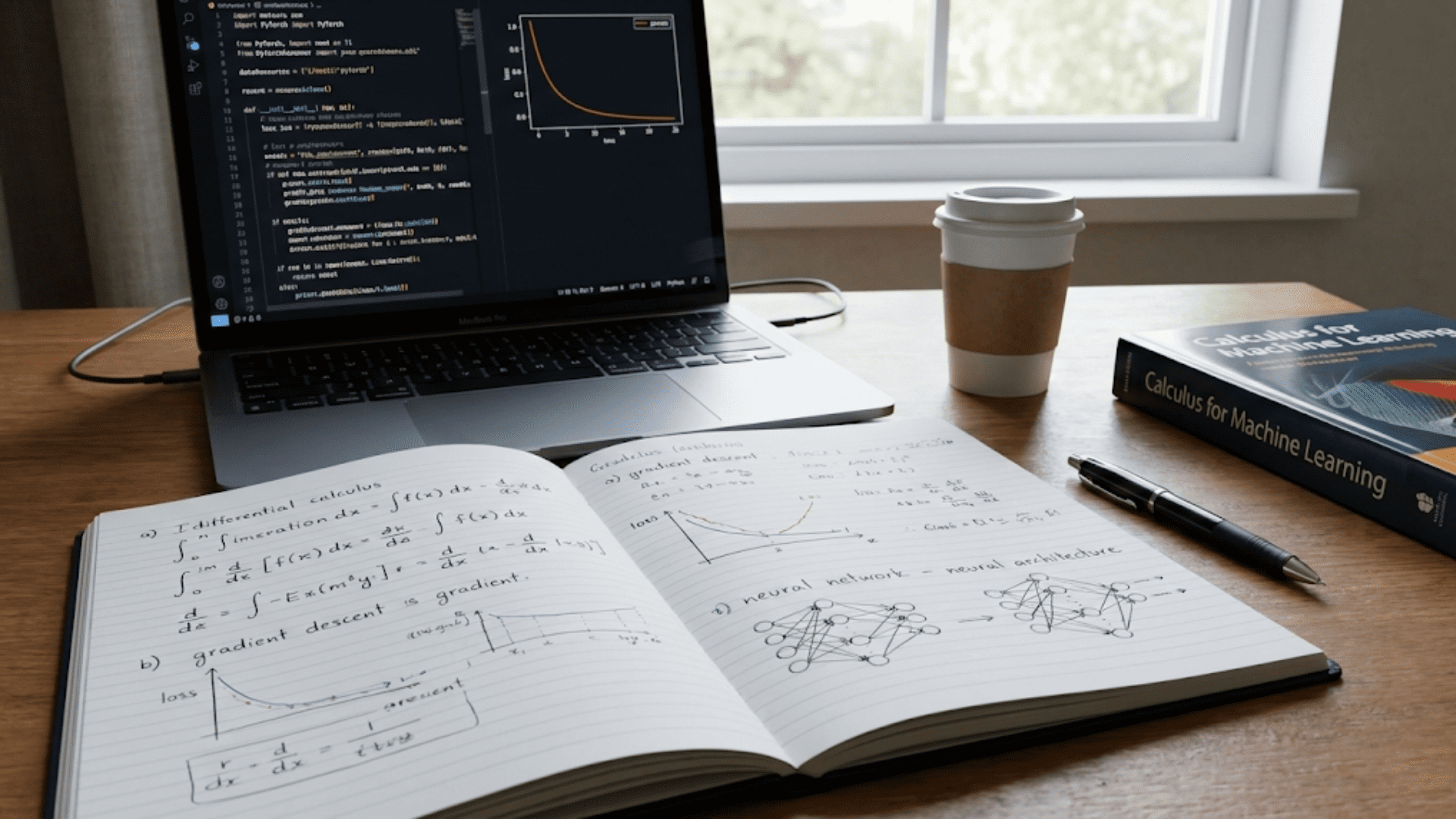

How This Differs from Traditional Python Development

In traditional Python development, you write a complete script in a .py file and run it from start to finish. The entire script executes in order every time, and you see results after everything completes. Debugging requires adding print statements or using a debugger. Documentation lives in separate files or comments within code.

Jupyter Notebooks invert this model. You build your program incrementally, executing small pieces and examining results as you go. You see variables’ values by simply typing their names. Visualizations appear inline immediately after generation. Documentation sits alongside code in markdown cells. This immediate feedback accelerates learning, debugging, and experimentation.

The tradeoff is structure. Scripts enforce a linear flow—code runs from line 1 to the end in order. Notebooks allow any execution order, which increases flexibility but can make reproducing results harder if you’re not disciplined about execution order and state management.

The Jupyter Interface: Navigation and Key Components

Understanding the Jupyter interface enables efficient work. While the interface is intuitive, knowing specific features and shortcuts dramatically accelerates your workflow.

The Dashboard: Your Notebook Home

When you launch Jupyter Notebook, the browser opens to the dashboard—a file browser showing notebooks, directories, and other files in your working directory. From here you create new notebooks, open existing ones, organize files into folders, upload files, and manage running kernels.

The dashboard shows which notebooks are currently running (indicated by a green book icon). This matters because running notebooks consume memory. When finished with a notebook, you should shut down its kernel from the dashboard to free resources. The “Running” tab shows all active notebooks and terminals, allowing you to shut them down centrally.

The Notebook Interface: Where Work Happens

Opening a notebook reveals the main interface where you’ll spend most of your time. The key components are:

The menu bar provides access to all notebook operations: File menu for saving, downloading, and managing notebooks; Edit menu for cutting, copying, and pasting cells; View menu for toggling toolbars and cell output; Insert menu for adding cells; Cell menu for running and managing cells; Kernel menu for restarting and managing the Python interpreter; and Help menu for documentation and keyboard shortcuts.

The toolbar offers quick access to common operations: save, add cell, cut, copy, paste, move cells up/down, run cell, stop execution, restart kernel, and cell type selector. While you’ll eventually prefer keyboard shortcuts, the toolbar helps when learning.

The cell area is where you write and execute code or markdown. Cells have two modes: edit mode (indicated by a green border) when you’re typing within a cell, and command mode (indicated by a blue border) when you’re navigating between cells. Understanding these modes is crucial because different keyboard shortcuts work in each mode.

The execution counter appears in square brackets before code cells, showing the order cells were executed. In [1] means this was the first cell run, In [2] the second, etc. An asterisk In [*] means the cell is currently executing. This counter helps you track execution order, which matters for reproducibility.

Essential Keyboard Shortcuts: Working at Speed

Keyboard shortcuts transform you from a slow clicker into a fast navigator. Learning these core shortcuts is one of the best time investments you can make.

Mode switching shortcuts:

- Enter: Enter edit mode (start typing in cell)

- Esc: Enter command mode (navigate between cells)

Command mode shortcuts (blue border):

- A: Insert cell above

- B: Insert cell below

- D, D (press D twice): Delete selected cell

- M: Convert cell to markdown

- Y: Convert cell to code

- Shift + Up/Down: Select multiple cells

- Shift + M: Merge selected cells

- C: Copy cell

- V: Paste cell

- Z: Undo cell deletion

Edit mode shortcuts (green border):

- Ctrl + Enter: Run cell, stay in current cell

- Shift + Enter: Run cell, move to next cell

- Alt + Enter: Run cell, insert new cell below

- Tab: Code completion or indent

- Shift + Tab: Show documentation (press multiple times for more detail)

Both modes:

- Ctrl + S or Cmd + S: Save notebook

These shortcuts seem numerous initially, but you’ll naturally memorize those you use frequently. Start with cell creation (A, B), execution (Shift + Enter), and mode switching (Enter, Esc). Add others gradually as you work.

Working with Code Cells: Interactive Python Execution

Code cells are where you write and execute Python. Understanding how to use them effectively is fundamental to productive Jupyter work.

Writing and Executing Code

A code cell can contain any valid Python code—a single expression, a function definition, an entire class, or multiple statements. You type code as you would in any editor, with the same syntax and rules. The difference is execution: instead of running an entire file, you execute just this cell’s code.

When you execute a cell (Shift + Enter or the Run button), Python runs the code and displays output below the cell. The output area shows whatever the code produces: return values, print statements, plots, tables, or error messages. If the code takes time to run, you’ll see In [*] indicating execution is in progress.

A powerful feature: the last expression’s value is automatically displayed without requiring print(). If a cell ends with a variable name or expression, Jupyter shows its value. This automatic display saves typing and makes exploration natural—just type a variable name to see its contents.

# Example of automatic output display

# Create a variable

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Last expression is automatically displayed

data # This will show [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]Managing Output

Cell output can be text, tables, visualizations, or even interactive widgets. Jupyter provides several ways to manage this output:

Clearing output: Right-click a cell and select “Clear Output” or use Cell menu → Current Outputs → Clear. This removes output without changing code, useful when outputs are large or you want a clean view.

Collapsing output: Click the output area’s left side to collapse it into a scrollable region. This helps when output is lengthy but you want to keep it available.

Suppressing output: End expressions with a semicolon to suppress automatic display. This is useful when a function returns a value you don’t need to see, like when creating plots that display automatically.

The Print Function vs Automatic Display

Understanding the difference between explicit printing and automatic display prevents confusion:

# Automatic display only shows the last expression

x = 5

y = 10

x + y # Only this is displayed: 15

# Print shows multiple values

x = 5

y = 10

print("x =", x)

print("y =", y)

print("sum =", x + y)Use print() when you need to see multiple values or want specific formatting. Use automatic display for quick inspection of single values.

Code Completion and Help

Jupyter provides powerful assistance while writing code. Press Tab while typing to see completion options for variables, functions, and methods. This works with imported libraries too—type pd. and press Tab to see all pandas functions.

Press Shift + Tab after a function name (with cursor inside the parentheses) to see its signature and documentation. Press it multiple times to expand the documentation panel. This inline help eliminates constant switching to documentation websites.

Example: A Complete Code Workflow

Let me show you a typical workflow in code cells:

# Cell 1: Import libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Cell 2: Load data

data = pd.DataFrame({

'feature1': np.random.randn(100),

'feature2': np.random.randn(100),

'target': np.random.randint(0, 2, 100)

})

# Cell 3: Explore data structure

data.head() # Automatically displays first 5 rows

# Cell 4: Check for missing values

data.isnull().sum() # Automatically displays counts

# Cell 5: Basic statistics

data.describe() # Automatically displays statistical summary

# Cell 6: Create visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.scatter(data['feature1'], data['feature2'], c=data['target'], cmap='viridis', alpha=0.6)

plt.xlabel('Feature 1')

plt.ylabel('Feature 2')

plt.title('Feature Relationship')

plt.colorbar(label='Target Class')

plt.show()

# Cell 7: Simple analysis

correlation = data[['feature1', 'feature2']].corr()

print("Feature correlation:")

print(correlation)What this workflow demonstrates: This example shows how Jupyter cells enable incremental development. Each cell performs a specific task and can be run independently. You can modify Cell 6’s visualization and rerun just that cell without reloading data or recalculating statistics. This iterative refinement is Jupyter’s core value proposition.

Working with Markdown Cells: Documentation and Narrative

Markdown cells transform notebooks from code execution environments into complete documents that combine analysis, results, and explanation. Understanding markdown enables clear, professional documentation.

Why Documentation Matters

Code without context is hard to understand, even for its author weeks later. Markdown cells let you explain what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and what you discovered. This documentation serves multiple purposes: it helps collaborators understand your work, reminds you of your reasoning when you return to a notebook months later, and creates shareable reports that explain findings to non-technical stakeholders.

Markdown Basics

Markdown is a lightweight markup language that converts to HTML. The syntax is intuitive and quick to write.

Headers organize content hierarchically:

# H1 - Main title

## H2 - Section

### H3 - Subsection

#### H4 - Sub-subsectionText formatting emphasizes important points:

**bold text** or __bold text__

*italic text* or _italic text_

***bold and italic***

~~strikethrough~~

`inline code` for variable names or short code snippetsLists organize information:

Unordered lists:

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Nested item

- Another nested item

Ordered lists:

1. First item

2. Second item

3. Third itemLinks connect to resources:

[Link text](https://example.com)

[Link to documentation](https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/)

Images illustrate concepts:

Code blocks show multi-line code without execution:

```python

def example_function(x):

return x * 2

```

LaTeX equations express mathematics:

Inline equation:

Display equation:

Structuring Your Notebook with Markdown

Well-structured notebooks follow a pattern similar to research papers:

Title and introduction (H1) describe the notebook’s purpose and goals.

Data loading section (H2) explains the data source and shows loading code.

Exploratory analysis section (H2) with subsections (H3) for different aspects: data quality checks, statistical summaries, visualizations.

Feature engineering section (H2) documenting transformations and why they were chosen.

Model building section (H2) explaining model selection, training process, and rationale.

Results and conclusions (H2) summarizing findings and next steps.

This structure makes notebooks scannable and professional. A reader can understand your work’s flow without executing cells.

Example: Documented Analysis

Here’s how markdown and code cells work together:

# Customer Churn Prediction Analysis

## Objective

Predict which customers are likely to churn (cancel service) based on usage patterns and demographics.

## Data Loading

We're using customer data from Q4 2024, containing 10,000 customer records with 15 features.# Load the customer dataset

import pandas as pd

customers = pd.read_csv('customer_data.csv')

print(f"Loaded {len(customers)} customer records")

print(f"Features: {len(customers.columns)}")## Initial Data Exploration

### Data Quality Check

First, we check for missing values and data type issues.# Check for missing values

missing = customers.isnull().sum()

print("Missing values per column:")

print(missing[missing > 0])### Key Findings

- Age has 150 missing values (1.5% of data) - will impute with median

- Income has 300 missing values (3% of data) - will impute with mean

- No duplicate customer IDs found

- All numerical columns have appropriate typesWhat this example demonstrates: Markdown cells provide context before and after code. Headers organize the analysis into sections. Explanations clarify why you’re performing operations. Key findings summarize results in plain language. This combination creates a self-documenting analysis that’s easy to follow and share.

Best Practices: Making Notebooks Maintainable and Reproducible

Jupyter’s flexibility can lead to messy, unreproducible notebooks if you’re not disciplined. Following best practices ensures your notebooks remain valuable long-term.

Execution Order Matters

The most common mistake is running cells out of order. Because cells can execute in any sequence, you might define a variable in a later cell, then use it in an earlier cell. This works during exploration but fails when you restart the kernel and run cells top-to-bottom.

Best practice: Periodically restart the kernel and run all cells from top to bottom (Kernel → Restart & Run All). This verifies your notebook executes correctly in order. If errors occur, reorganize cells until the notebook runs cleanly from start to finish.

Why this matters: When you share notebooks or return to them later, they should run correctly without manual intervention. A notebook that only works with specific execution order is effectively broken.

Keep Cells Focused

Each cell should do one thing: load data, create a plot, calculate statistics, train a model. Avoid massive cells containing dozens of operations. Short, focused cells are easier to debug, modify, and understand.

Bad example:

# Cell doing too much

data = pd.read_csv('data.csv')

data = data.dropna()

data['new_feature'] = data['col1'] * data['col2']

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(data[['new_feature']], data['target'])

predictions = model.predict(data[['new_feature']])

plt.scatter(data['new_feature'], data['target'])

plt.plot(data['new_feature'], predictions, color='red')

accuracy = model.score(data[['new_feature']], data['target'])

print(f"R² = {accuracy}")Good example:

# Cell 1: Load data

data = pd.read_csv('data.csv')

# Cell 2: Clean data

data = data.dropna()

# Cell 3: Feature engineering

data['new_feature'] = data['col1'] * data['col2']

# Cell 4: Train model

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(data[['new_feature']], data['target'])

# Cell 5: Visualize

predictions = model.predict(data[['new_feature']])

plt.scatter(data['new_feature'], data['target'], alpha=0.6, label='Actual')

plt.plot(data['new_feature'], predictions, color='red', linewidth=2, label='Predicted')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

# Cell 6: Evaluate

accuracy = model.score(data[['new_feature']], data['target'])

print(f"R² = {accuracy:.4f}")The second version is easier to modify (change just the visualization without retraining), debug (errors point to specific operations), and understand (each cell has a clear purpose).

Organize Imports at the Top

Place all imports in the first code cell after your title. This makes dependencies clear and prevents import errors when running cells out of order.

# Cell 1: Imports

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, classification_reportDocument Your Reasoning

Don’t just explain what code does—explain why you’re doing it. Code comments explain how; markdown cells explain why.

## Handling Missing Values

We choose median imputation for age instead of mean because age distribution is right-skewed. The median (35) is more representative of typical customers than the mean (38), which is pulled up by a few elderly outliers.

For income, we use mean imputation because the distribution is roughly symmetric and mean preserves the total income across the dataset.Save Regularly

Jupyter autosaves periodically, but develop the habit of saving manually (Ctrl+S) after significant changes. Notebooks can crash, browsers can close, and unsaved work is lost. Create a keyboard muscle memory for frequent saving.

Version Control

Consider using version control (Git) for important notebooks. Jupyter notebooks are JSON files that can be tracked with Git, though the format makes diffs less readable than pure code files. Tools like nbdime improve notebook diffing.

For critical projects, consider keeping notebooks under version control and committing after completing each major section. This creates a history you can reference if you need to revert changes.

Clear Output Before Committing

When sharing notebooks or committing to version control, clear all output (Cell → All Output → Clear). This reduces file size and ensures recipients see fresh results when running cells themselves. Large plots or dataframes in output can make notebook files megabytes in size.

State Management Awareness

Be conscious of kernel state. Variables persist until you restart the kernel. If you define x = 5 in a cell then delete that cell, x still exists in memory. This can cause confusion.

Periodically restart the kernel to start fresh. This clears all variables and imports, forcing you to re-run cells in order. This discipline prevents relying on hidden state that won’t exist in a clean execution.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Understanding common mistakes helps you avoid them and recognize them when they occur.

Pitfall 1: The Hidden State Problem

Problem: You define a variable, use it in multiple cells, then modify the definition. Some cells still use the old value because you didn’t rerun them.

Solution: After changing variable definitions, rerun all cells that depend on that variable. Better yet, periodically restart the kernel and run all cells to verify everything works from scratch.

Pitfall 2: Execution Order Confusion

Problem: Your notebook works during exploration but fails when run top-to-bottom because cells were executed in a different order than they appear.

Solution: Organize cells in the order they should execute. Before considering work complete, restart kernel and run all cells from top to bottom to verify reproducibility.

Pitfall 3: Massive Cells

Problem: Cells containing hundreds of lines are hard to debug and modify.

Solution: Split large cells into logical units. Each cell should perform one clear task. If you need to modify one part, you shouldn’t need to rerun unrelated code in the same cell.

Pitfall 4: No Documentation

Problem: Months later, you or others can’t understand what the notebook does or why.

Solution: Add markdown cells explaining the purpose, approach, and reasoning. Document assumptions, decisions, and discoveries. Your future self will thank you.

Pitfall 5: Treating Notebooks Like Scripts

Problem: Writing one long script in cells as if it were a .py file, not leveraging interactive execution.

Solution: Embrace the interactive workflow. Execute cells incrementally. Examine intermediate results. Iterate on visualizations. This is Jupyter’s strength.

Pitfall 6: Not Restarting the Kernel

Problem: Relying on variables or imports that aren’t visible in the notebook because you defined them then deleted those cells.

Solution: Regularly restart the kernel and run all cells. This verifies the notebook is self-contained and reproducible.

Advanced Features: Taking Jupyter Further

Once comfortable with basics, several advanced features enhance productivity.

Magic Commands

Magic commands are special Jupyter commands that aren’t Python syntax. They start with % (line magics) or %% (cell magics).

Useful line magics:

%time statement # Time a single statement

%timeit statement # Time statement over multiple runs for accurate measurement

%matplotlib inline # Display plots inline (default in modern Jupyter)

%load script.py # Load code from file into cell

%run script.py # Execute Python script

%who # List all variables

%whos # Detailed list of variablesUseful cell magics:

%%time

# Times entire cell execution

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('large_file.csv')

processed = data.groupby('category').mean()

%%writefile script.py

# Writes cell contents to file

def my_function(x):

return x * 2IPython Display System

Jupyter’s display system supports rich output beyond text:

from IPython.display import Image, HTML, Markdown, display

# Display image

display(Image('diagram.png'))

# Display HTML table

display(HTML('<table><tr><td>Cell 1</td><td>Cell 2</td></tr></table>'))

# Display formatted markdown

display(Markdown('## This is a heading\n\nThis is **bold** text.'))

Shell Commands

Run shell commands by prefixing with !:

!ls # List files

!pwd # Print working directory

!pip install package_name # Install packages

!git status # Git commandsThis is useful for file management, environment setup, and integrating with command-line tools.

Variable Inspection

Examine variables interactively:

# Last expression shows value

x = [1, 2, 3]

x # Shows [1, 2, 3]

# Show type

type(x) # Shows <class 'list'>

# Show attributes and methods

dir(x) # Shows all attributes/methods

# Get help

help(x.append) # Shows documentation

x.append? # Alternative help syntaxConclusion: Mastering Interactive Machine Learning Development

Jupyter Notebooks have become the standard environment for machine learning development because they perfectly match how data scientists work. The ability to write code, see results immediately, adjust based on those results, and document your process all in one place makes Jupyter indispensable for exploration, experimentation, and communication.

The skills covered in this guide—understanding the architecture and interface, working effectively with code and markdown cells, following best practices for reproducibility, and avoiding common pitfalls—transform you from a Jupyter beginner into a productive user. You now understand not just how to create and run cells, but how to organize notebooks for clarity, document your work for others, and maintain reproducibility.

As you develop your machine learning skills, Jupyter Notebooks will be your primary environment for data exploration, model experimentation, and result presentation. You’ll load datasets and immediately visualize distributions. You’ll try different preprocessing approaches and compare results. You’ll train models with various hyperparameters and evaluate performance. You’ll create visualizations explaining your findings to stakeholders. All of this happens fluidly in notebooks.

The key to Jupyter mastery is practice with real projects. Don’t just read about notebooks—use them for your data analysis. Start small: load a dataset, explore it, create some visualizations. Gradually incorporate more advanced features: markdown documentation, magic commands, keyboard shortcuts. Develop good habits early: regular kernel restarts, clear execution order, focused cells, comprehensive documentation.

Remember that Jupyter Notebooks are tools, not solutions. They excel at exploration, iteration, and communication but aren’t ideal for all programming tasks. Large applications, production code, and automated processes typically belong in Python scripts and modules. Use notebooks for what they do best: interactive analysis, experimentation, and presenting results. For production code, refactor polished functions from notebooks into .py files that you import and use.

The interactive workflow Jupyter enables is more than a convenience—it’s a fundamentally different and more effective way to work with data and build machine learning models. Embrace this interactive approach, follow best practices for reproducibility, and leverage Jupyter’s strengths to accelerate your machine learning development.