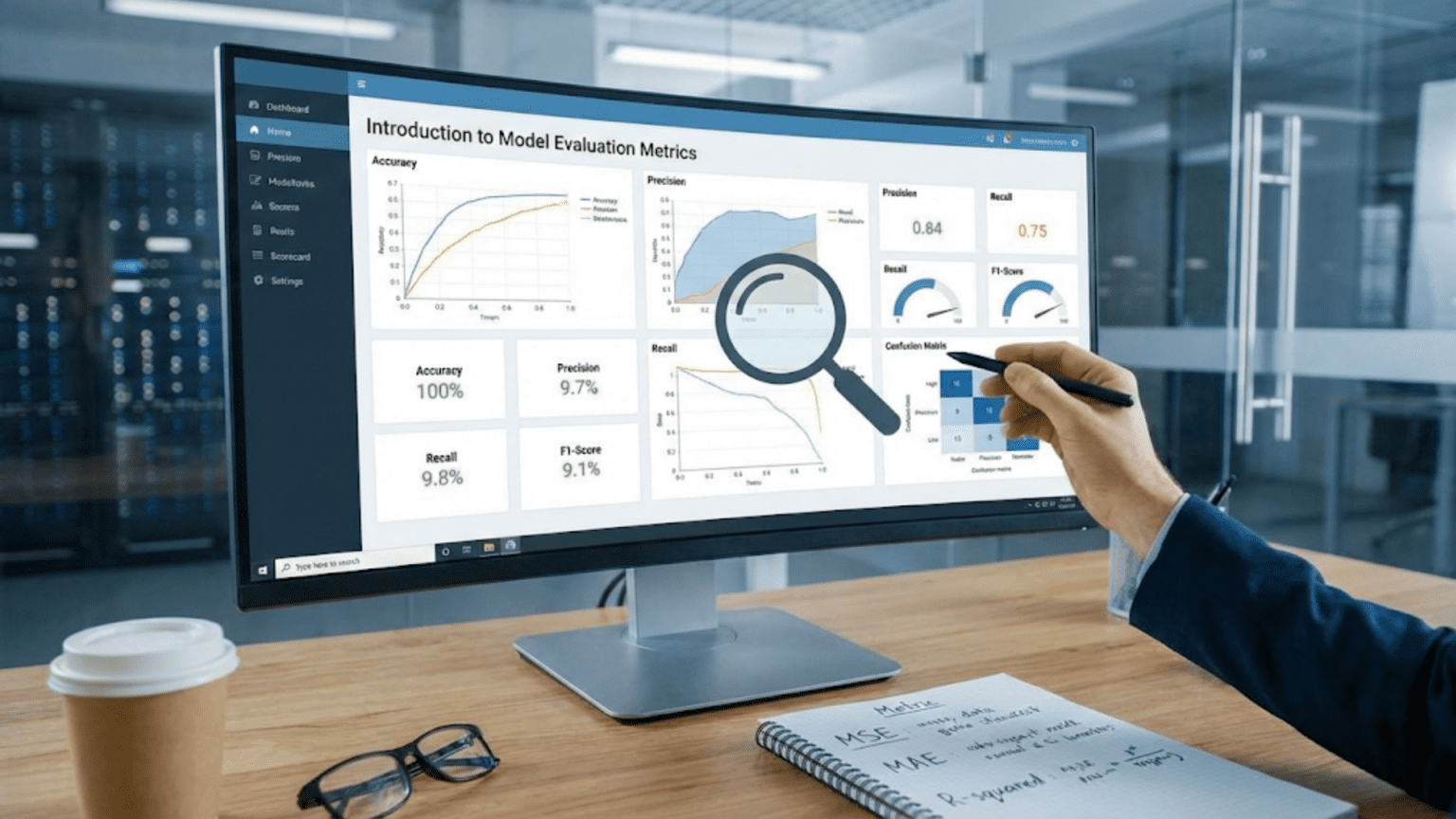

Model evaluation metrics quantify how well machine learning models perform by comparing predictions to actual values. Classification metrics include accuracy (overall correctness), precision (correctness of positive predictions), recall (finding all positives), F1-score (balance of precision and recall), and ROC-AUC (discrimination ability). Regression metrics include MAE (average error magnitude), RMSE (error with penalty for large mistakes), and R² (variance explained). Choosing appropriate metrics depends on the problem type, class balance, and business objectives.

Introduction: Measuring What Matters

Imagine evaluating a medical diagnostic test without any standardized way to measure its performance. How would you know if it’s reliable? How would you compare it to alternative tests? How would you decide whether it’s good enough for clinical use? You need objective, quantifiable metrics—numbers that tell you how well the test actually works.

Machine learning faces the exact same challenge. After training a model, you need to answer critical questions: Is it any good? Is it better than the baseline? Should we deploy it? Which of five candidate models performs best? These questions demand objective answers, not gut feelings or wishful thinking.

Model evaluation metrics provide those objective answers. They translate model performance into concrete numbers you can compare, track over time, and use to make data-driven decisions. Without proper metrics, you’re flying blind—unable to distinguish excellent models from terrible ones, or know whether changes actually improve performance.

Yet choosing and interpreting metrics isn’t straightforward. A model with 95% accuracy might be worse than one with 80% accuracy depending on the problem. Precision and recall tell you different things, and optimizing one often hurts the other. Some metrics are sensitive to class imbalance while others aren’t. Using inappropriate metrics leads to poor decisions: deploying ineffective models, rejecting good ones, or optimizing for the wrong objective.

This comprehensive guide introduces the essential evaluation metrics for machine learning. You’ll learn what each metric measures, when to use it, how to interpret it, and which metrics matter for different types of problems. We’ll cover classification metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, as well as regression metrics like MAE, RMSE, and R². With practical examples throughout, you’ll develop intuition for choosing appropriate metrics and interpreting them correctly.

Whether you’re evaluating your first model or refining production systems, understanding evaluation metrics is fundamental to machine learning success.

Why Evaluation Metrics Matter

Before diving into specific metrics, let’s understand why they’re essential.

Objective Performance Assessment

Problem Without Metrics:

"The model seems pretty good!"

"It works most of the time."

"I think it's better than the old system."These subjective assessments are useless for making important decisions.

Solution With Metrics:

"The model achieves 87% accuracy, 82% precision, and 91% recall."

"It improves over the baseline by 12 percentage points."

"On the test set, it has an AUC of 0.93."Metrics provide concrete, comparable numbers.

Model Comparison

Scenario: You’ve trained five different models. Which is best?

Without Metrics: Guesswork, cherry-picking examples, subjective judgment

With Metrics:

Model A: Accuracy=82%, F1=0.79

Model B: Accuracy=79%, F1=0.84

Model C: Accuracy=85%, F1=0.73

Decision depends on whether you prioritize accuracy or F1

But at least you have objective data to compareOptimization Guidance

Iterative Improvement:

- Baseline: Accuracy=72%

- Add features: Accuracy=76% (improved!)

- Regularization: Accuracy=78% (improved more!)

- Different algorithm: Accuracy=74% (worse, revert)

Metrics tell you whether changes help or hurt.

Deployment Decisions

Business Question: Is this model ready for production?

Threshold Decision:

Minimum acceptable accuracy: 80%

Model performance: 82%

Decision: Deploy ✓

Model performance: 76%

Decision: Don't deploy ✗ (needs improvement)Monitoring and Maintenance

Production Tracking:

Week 1: Accuracy=82% (matches test set)

Week 2: Accuracy=81% (small drop, normal)

Week 3: Accuracy=78% (concerning)

Week 4: Accuracy=71% (alert! retrain needed)Metrics detect performance degradation.

Classification Metrics: Evaluating Category Predictions

Classification metrics evaluate models that predict discrete categories or classes.

Confusion Matrix: The Foundation

Before understanding metrics, you must understand the confusion matrix—a table showing prediction outcomes.

Binary Classification Example: Spam detection

Predicted

Spam Not Spam

Actual Spam 90 10 (100 actual spam)

Not Spam 20 880 (900 actual not spam)Four Key Outcomes:

True Positives (TP): 90

- Correctly predicted spam (actual=spam, predicted=spam)

False Negatives (FN): 10

- Missed spam (actual=spam, predicted=not spam)

- Also called “Type II errors”

False Positives (FP): 20

- Incorrectly flagged as spam (actual=not spam, predicted=spam)

- Also called “Type I errors”

True Negatives (TN): 880

- Correctly predicted not spam (actual=not spam, predicted=not spam)

Total: 1,000 emails

All classification metrics derive from these four numbers.

Accuracy: Overall Correctness

Definition: Percentage of predictions that are correct

Formula:

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

= Correct predictions / Total predictionsExample:

Accuracy = (90 + 880) / (90 + 880 + 20 + 10)

= 970 / 1000

= 0.97 or 97%Interpretation: 97% of emails were correctly classified.

When to Use:

- Balanced classes (similar number of positives and negatives)

- Equal cost for all errors

- Simple overview of performance

When NOT to Use:

- Imbalanced classes (accuracy can be misleading)

- Different costs for different error types

Imbalanced Example:

Fraud detection: 990 legitimate, 10 fraudulent transactions

Model that predicts everything as "legitimate":

Accuracy = 990/1000 = 99%

But it catches 0% of fraud!

High accuracy, completely useless modelKey Insight: Accuracy can be misleading. Need additional metrics.

Precision: Correctness of Positive Predictions

Definition: Of all positive predictions, how many were actually positive?

Formula:

Precision = TP / (TP + FP)

= True Positives / All Predicted PositivesExample (spam detection):

Precision = 90 / (90 + 20)

= 90 / 110

= 0.818 or 81.8%Interpretation: When the model says “spam,” it’s correct 81.8% of the time.

Other Names: Positive Predictive Value (PPV)

When to Prioritize:

- False positives are costly

- You want to be sure when you predict positive

Real-World Examples:

Email Spam Filter:

- False positive = legitimate email goes to spam (very annoying)

- Want high precision to minimize false positives

- Better to let some spam through than block important emails

Medical Screening for Expensive/Invasive Followup:

- Positive prediction triggers expensive tests or surgery

- Want high precision to avoid unnecessary procedures

- Minimize false alarms

Marketing Campaign:

- Positive prediction = send promotional offer

- High precision means offers go to likely buyers

- Don’t waste money on unlikely customers

Recall: Finding All Positives

Definition: Of all actual positives, how many did we find?

Formula:

Recall = TP / (TP + FN)

= True Positives / All Actual PositivesExample (spam detection):

Recall = 90 / (90 + 10)

= 90 / 100

= 0.90 or 90%Interpretation: The model found 90% of all spam emails.

Other Names: Sensitivity, True Positive Rate, Hit Rate

When to Prioritize:

- False negatives are costly

- You want to find all positives, even at cost of false alarms

Real-World Examples:

Cancer Screening:

- False negative = missing cancer (potentially fatal)

- Want high recall to catch all cases

- Better to have false alarms than miss cancer

Fraud Detection:

- False negative = fraud goes undetected (loses money)

- Want high recall to catch all fraud

- Can manually review false positives

Search Engines:

- False negative = relevant result not shown

- Want high recall to show all relevant results

- User can ignore irrelevant results (false positives)

The Precision-Recall Tradeoff

Fundamental Tension: Improving precision often hurts recall and vice versa.

Example: Spam filter threshold

Very Conservative (high threshold for spam):

Only flag emails you're very confident are spam

Result: High precision (when you say spam, you're right)

But: Low recall (you miss lots of spam)Very Aggressive (low threshold):

Flag anything remotely suspicious as spam

Result: High recall (catch almost all spam)

But: Low precision (flag many legitimate emails)Visualization:

Precision ↑ → Recall ↓

Precision ↓ → Recall ↑Balancing Act: Choose threshold based on which errors cost more.

F1-Score: Harmonic Mean of Precision and Recall

Purpose: Single metric balancing precision and recall

Formula:

F1 = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall)Example (spam detection):

Precision = 0.818, Recall = 0.90

F1 = 2 × (0.818 × 0.90) / (0.818 + 0.90)

= 2 × 0.7362 / 1.718

= 0.857 or 85.7%Why Harmonic Mean?: Harmonic mean punishes extreme values more than arithmetic mean.

Example:

Precision=0.9, Recall=0.9 → F1=0.90 (both good)

Precision=0.9, Recall=0.5 → F1=0.64 (one bad, F1 much lower)

Precision=1.0, Recall=0.1 → F1=0.18 (extreme case, F1 very low)You can’t game F1 by maximizing just one metric.

When to Use:

- Need balance between precision and recall

- Don’t want to optimize one at expense of the other

- Standard metric for many competitions

Variants:

F2-Score: Weights recall higher than precision

F2 = 5 × (Precision × Recall) / (4 × Precision + Recall)Use when recall more important.

F0.5-Score: Weights precision higher than recall

F0.5 = 1.25 × (Precision × Recall) / (0.25 × Precision + Recall)Use when precision more important.

Specificity: Correctly Identifying Negatives

Definition: Of all actual negatives, how many were correctly identified?

Formula:

Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

= True Negatives / All Actual NegativesExample (spam detection):

Specificity = 880 / (880 + 20)

= 880 / 900

= 0.978 or 97.8%Interpretation: Model correctly identifies 97.8% of legitimate emails.

Other Names: True Negative Rate

When Important:

- Need to correctly identify negatives

- Medical testing (identifying healthy patients)

- Quality control (identifying good products)

ROC Curve and AUC: Threshold-Independent Evaluation

ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) Curve: Plot showing model performance across all classification thresholds.

Axes:

- X-axis: False Positive Rate (FPR) = FP / (FP + TN) = 1 – Specificity

- Y-axis: True Positive Rate (TPR) = Recall

How It Works:

Models typically output probabilities (0-1) for positive class. You choose threshold to convert to binary prediction:

Threshold = 0.9: Only very confident predictions → High precision, low recall

Threshold = 0.5: Balanced threshold

Threshold = 0.1: Liberal predictions → Low precision, high recallROC curve plots TPR vs. FPR for all possible thresholds.

Interpretation:

Perfect Classifier:

- TPR = 1.0, FPR = 0.0 for all thresholds

- Curve hugs top-left corner

Good Classifier:

- Curve bows toward top-left

- High TPR with low FPR

Random Classifier:

- Diagonal line from (0,0) to (1,1)

- TPR = FPR (no discrimination ability)

Worse Than Random:

- Curve below diagonal

- (Just invert predictions to be above random)

AUC (Area Under Curve):

Definition: Area under the ROC curve, single number summarizing ROC performance

Range: 0 to 1

Interpretation:

AUC = 1.0: Perfect classifier

AUC = 0.9-1.0: Excellent

AUC = 0.8-0.9: Good

AUC = 0.7-0.8: Fair

AUC = 0.6-0.7: Poor

AUC = 0.5: Random (no discrimination)

AUC < 0.5: Worse than random (invert predictions)Practical Meaning: Probability that model ranks random positive example higher than random negative example.

When to Use:

- Want threshold-independent evaluation

- Care about ranking quality

- Comparing models across different threshold choices

- Imbalanced datasets (less sensitive to imbalance than accuracy)

Advantages:

- Single number summary

- Threshold-independent

- Works well with imbalanced data

Disadvantages:

- Doesn’t tell you performance at specific threshold

- Doesn’t distinguish types of errors

- May not align with business metric

Multi-Class Classification Metrics

Extensions for >2 Classes:

Macro-Averaging: Calculate metric for each class, average them

Macro-Precision = (Precision_Class1 + Precision_Class2 + Precision_Class3) / 3Treats all classes equally.

Micro-Averaging: Pool all predictions, calculate metric globally

Micro-Precision = Sum(TP_all_classes) / Sum(TP_all_classes + FP_all_classes)Weighted by class frequency.

Weighted-Averaging: Weight by class support (number of instances)

When to Use Each:

- Macro: Classes equally important

- Micro: Weighted by frequency makes sense

- Weighted: Balance between macro and micro

Example: Digit recognition (0-9)

- Macro F1: Average F1 across all 10 digits

- Micro F1: Overall F1 pooling all predictions

- Weighted F1: Weight digit F1s by frequency in test set

Regression Metrics: Evaluating Continuous Predictions

Regression metrics evaluate models predicting continuous numerical values.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

Definition: Average absolute difference between predictions and actual values

Formula:

Example: House price prediction (in thousands)

House 1: Actual=$300k, Predicted=$320k, Error=20

House 2: Actual=$400k, Predicted=$380k, Error=20

House 3: Actual=$250k, Predicted=$240k, Error=10

MAE = (20 + 20 + 10) / 3 = 16.67

Average error is $16,670Characteristics:

- Simple, intuitive interpretation

- Same units as target variable

- Linear penalty (all errors weighted equally)

- Robust to outliers (compared to MSE)

When to Use:

- Want intuitive, interpretable metric

- All errors equally important (small and large)

- Outliers present in data

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

Definition: Average squared difference between predictions and actual values

Formula:

Example: Same house prices

House 1: Error=20, Squared=400

House 2: Error=20, Squared=400

House 3: Error=10, Squared=100

MSE = (400 + 400 + 100) / 3 = 300Characteristics:

- Squared units (harder to interpret)

- Quadratic penalty (large errors penalized heavily)

- Sensitive to outliers

- Differentiable (useful for optimization)

When to Use:

- Large errors particularly undesirable

- Want to penalize outliers heavily

- Optimization convenience (gradient descent)

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

Definition: Square root of MSE

Formula:

Example:

RMSE = √300 = 17.32

Average error is $17,320 (with larger errors weighted more)Characteristics:

- Same units as target variable (like MAE)

- Still penalizes large errors more (like MSE)

- Most commonly used regression metric

When to Use:

- Want interpretable units

- Large errors matter more than small errors

- Standard metric for many problems

MAE vs RMSE:

If all errors similar: MAE ≈ RMSE

If outliers present: RMSE > MAE (more sensitive)

Example:

Errors: [10, 10, 10, 10, 10]

MAE = 10, RMSE = 10 (same)

Errors: [5, 5, 5, 5, 50]

MAE = 14, RMSE = 22.7 (RMSE much higher due to outlier)R² (R-Squared / Coefficient of Determination)

Definition: Proportion of variance in target variable explained by model

Formula:

Range: -∞ to 1 (typically 0 to 1)

Interpretation:

R² = 1.0: Perfect predictions

R² = 0.8: Model explains 80% of variance

R² = 0.5: Model explains 50% of variance

R² = 0.0: Model no better than predicting mean

R² < 0.0: Model worse than predicting meanExample:

Actual prices: [200, 300, 400, 500] (mean=350)

Predicted: [220, 310, 380, 490]

Sum of Squared Residuals = (200-220)² + (300-310)² + (400-380)² + (500-490)²

= 400 + 100 + 400 + 100 = 1000

Total Sum of Squares = (200-350)² + (300-350)² + (400-350)² + (500-350)²

= 22500 + 2500 + 2500 + 22500 = 50000

R² = 1 - (1000/50000) = 1 - 0.02 = 0.98

Model explains 98% of varianceCharacteristics:

- Scale-independent (unlike RMSE, MAE)

- Easy comparison across problems

- Can be misleading with complex models (adjusted R² better)

When to Use:

- Want scale-independent metric

- Comparing models on different datasets

- Understanding explanatory power

Limitations:

- Increases with more features (even irrelevant ones)

- Can be negative on test set

- Doesn’t indicate prediction accuracy directly

Adjusted R²: Penalizes model complexity

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)

Definition: Average absolute percentage error

Formula:

Example:

House 1: Actual=$300k, Predicted=$320k, Error=6.67%

House 2: Actual=$400k, Predicted=$380k, Error=5%

House 3: Actual=$250k, Predicted=$240k, Error=4%

MAPE = (6.67 + 5 + 4) / 3 = 5.22%Interpretation: Average error is 5.22% of actual value

When to Use:

- Want percentage-based metric

- Comparing across different scales

- Communicating to non-technical stakeholders

Limitations:

- Undefined when actual=0

- Asymmetric (penalizes over-predictions more than under-predictions)

- Sensitive to small actual values

Choosing the Right Metrics: Decision Framework

Problem Type Determines Initial Set:

Classification Problems

Binary Classification:

- Balanced classes: Accuracy, F1-Score

- Imbalanced classes: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC

- Ranking quality important: AUC

- Specific threshold needed: Precision, Recall at that threshold

Multi-Class Classification:

- Balanced classes: Accuracy, Macro-F1

- Imbalanced classes: Weighted-F1, Micro-F1

- Each class important: Macro metrics

- Frequency matters: Micro/Weighted metrics

Regression Problems

Continuous Predictions:

- Interpretable error magnitude: MAE

- Penalize large errors: RMSE

- Scale-independent: R²

- Percentage terms: MAPE

Cost Considerations

Different Error Costs:

Example 1: Fraud Detection

- False Negative (miss fraud) costs $1000

- False Positive (block legitimate) costs $10 → Optimize Recall, accept lower Precision

Example 2: Spam Filter

- False Positive (block important email) costs $100

- False Negative (spam in inbox) costs $1 → Optimize Precision, accept lower Recall

Custom Metrics: Weight errors by business cost

Domain Requirements

Medical Diagnosis:

- High recall critical (can’t miss diseases)

- Use Recall and AUC

Credit Scoring:

- Balance precision (don’t approve bad loans) and recall (don’t reject good customers)

- Use F1-Score

Recommendation Systems:

- Precision@K (precision in top K recommendations)

- NDCG (ranking quality)

Stakeholder Communication

Technical Audience: Any metric with proper explanation Business Stakeholders: Simple, interpretable metrics

- Accuracy (if appropriate)

- Error rate

- Cost-based metrics

- Percentage improvements

Practical Example: Comparing Models with Multiple Metrics

Problem: Email spam classification

Dataset: 10,000 emails (1,000 spam, 9,000 legitimate)

Three Models Trained:

Model A: Logistic Regression

Confusion Matrix:

Predicted

Spam Not Spam

Actual Spam 820 180

Not Spam 100 8900Metrics:

Accuracy = (820 + 8900) / 10000 = 97.2%

Precision = 820 / (820 + 100) = 89.1%

Recall = 820 / (820 + 180) = 82.0%

F1-Score = 2 × (0.891 × 0.820) / (0.891 + 0.820) = 85.4%

Specificity = 8900 / (8900 + 100) = 98.9%Model B: Random Forest

Confusion Matrix:

Predicted

Spam Not Spam

Actual Spam 900 100

Not Spam 300 8700Metrics:

Accuracy = (900 + 8700) / 10000 = 96.0%

Precision = 900 / (900 + 300) = 75.0%

Recall = 900 / (900 + 100) = 90.0%

F1-Score = 2 × (0.75 × 0.90) / (0.75 + 0.90) = 81.8%

Specificity = 8700 / (8700 + 300) = 96.7%Model C: Neural Network

Confusion Matrix:

Predicted

Spam Not Spam

Actual Spam 870 130

Not Spam 80 8920Metrics:

Accuracy = (870 + 8920) / 10000 = 97.9%

Precision = 870 / (870 + 80) = 91.6%

Recall = 870 / (870 + 130) = 87.0%

F1-Score = 2 × (0.916 × 0.870) / (0.916 + 0.870) = 89.2%

Specificity = 8920 / (8920 + 80) = 99.1%Comparison Table

| Metric | Model A | Model B | Model C | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 97.2% | 96.0% | 97.9% | C |

| Precision | 89.1% | 75.0% | 91.6% | C |

| Recall | 82.0% | 90.0% | 87.0% | B |

| F1-Score | 85.4% | 81.8% | 89.2% | C |

| Specificity | 98.9% | 96.7% | 99.1% | C |

Decision Analysis

If Minimizing False Positives is Critical (high precision needed): → Choose Model C (91.6% precision) Reason: Blocking legitimate emails very costly

If Finding All Spam is Critical (high recall needed): → Choose Model B (90.0% recall) Reason: Missing spam very annoying

If Balanced Performance Desired: → Choose Model C (highest F1, accuracy) Reason: Best overall balance

Business Context Example:

Personal email: False positives very costly (miss important emails)

→ Choose Model C for high precision

Corporate email: Spam very disruptive

→ Choose Model B for high recallFinal Choice: Model C

- Highest accuracy, precision, F1, and specificity

- Slightly lower recall than B (87% vs 90%)

- But much better precision (91.6% vs 75%)

- Better overall balance for most use cases

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Pitfall 1: Using Accuracy for Imbalanced Data

Problem: Accuracy misleading when classes imbalanced

Example:

Dataset: 99% class A, 1% class B

Model that always predicts A: 99% accuracy

But completely fails at finding class BSolution: Use precision, recall, F1, or AUC for imbalanced data

Pitfall 2: Optimizing Wrong Metric

Problem: Optimizing metric that doesn’t align with business goal

Example:

Medical diagnosis:

Model optimized for accuracy: 95%

But: Only 60% recall (misses 40% of diseases)

Business goal: Catch all diseases (high recall needed)Solution: Choose metrics aligned with business objectives

Pitfall 3: Ignoring Metric Limitations

Problem: Every metric has blind spots

Example with Accuracy:

- Doesn’t distinguish error types

- Sensitive to class imbalance

Example with R²:

- Increases with more features

- Can be negative on test set

- Doesn’t indicate prediction accuracy

Solution: Use multiple complementary metrics

Pitfall 4: Overfitting to Validation Metrics

Problem: Optimizing so much on validation set that you overfit to it

Example:

Try 100 different models

Pick best validation accuracy

Validation: 92%

Test: 84% (much worse!)Solution: Use separate test set for final evaluation

Pitfall 5: Not Considering Uncertainty

Problem: Single metric without confidence intervals

Example:

Model A: 82% accuracy

Model B: 83% accuracy

Are these meaningfully different?

Depends on sample size and variance!

With 95% confidence intervals:

Model A: 82% ± 3% → [79%, 85%]

Model B: 83% ± 4% → [79%, 87%]

Ranges overlap significantly → No clear winnerSolution: Report confidence intervals or statistical significance

Pitfall 6: Inconsistent Evaluation

Problem: Different evaluation protocols for different models

Example:

Model A evaluated on clean test set

Model B evaluated on test set with preprocessing errors

Unfair comparisonSolution: Identical evaluation for all models

Advanced Metrics and Specialized Domains

Ranking Metrics

Precision@K: Precision in top K predictions

Recommended 10 products, 7 relevant

Precision@10 = 7/10 = 70%Mean Average Precision (MAP): Average precision across queries

NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain): Considers ranking order

- Relevant items at top ranked higher

- Discounts value of relevant items lower in ranking

Time Series Metrics

MASE (Mean Absolute Scaled Error): Scaled by naive forecast

Forecast Accuracy: Specific thresholds (within 5%, 10%)

Clustering Metrics

Silhouette Score: How well-separated clusters are (-1 to 1)

Davies-Bouldin Index: Average similarity between clusters (lower better)

Adjusted Rand Index: Agreement with ground truth labels

Information Retrieval

Precision: Relevant / Retrieved

Recall: Relevant / Total Relevant

F1: Harmonic mean

MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank): Rank of first relevant result

Best Practices for Using Metrics

During Development

- Use multiple metrics: Don’t rely on single number

- Align with business goals: Metrics should reflect what matters

- Monitor both training and validation: Detect overfitting

- Establish baselines: Know what you’re trying to beat

- Document metric choices: Explain why you chose them

For Model Selection

- Primary metric: Choose one main metric for decisions

- Secondary metrics: Monitor others for holistic view

- Thresholds: Define acceptable performance levels

- Trade-offs: Understand what you’re optimizing for

In Production

- Continuous monitoring: Track metrics over time

- Alert thresholds: Detect degradation early

- A/B testing: Compare models on live data

- Business metrics: Connect to actual outcomes

Comparison: Metric Selection Guide

| Scenario | Recommended Metrics | Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced binary classification | Accuracy, F1-Score, AUC | Precision/Recall alone |

| Imbalanced classification | Precision, Recall, F1, AUC | Accuracy |

| High cost of false positives | Precision | Recall |

| High cost of false negatives | Recall | Precision |

| Multi-class balanced | Accuracy, Macro-F1 | Micro metrics |

| Multi-class imbalanced | Weighted-F1, AUC | Accuracy |

| Regression, interpretable error | MAE, RMSE | R² alone |

| Regression, penalize outliers | RMSE | MAE |

| Regression, scale-independent | R², MAPE | MSE |

| Ranking quality | AUC, NDCG, MAP | Accuracy |

| Communicating to business | Accuracy (if appropriate), Error rate, Cost | Complex metrics without explanation |

Conclusion: Measuring Success in Machine Learning

Model evaluation metrics transform vague questions like “is this model good?” into concrete, actionable answers. They provide the objective foundation for comparing models, guiding optimization, making deployment decisions, and monitoring production performance.

Understanding metrics deeply means knowing not just formulas, but what each metric actually measures, when it’s appropriate, and what it doesn’t tell you:

Accuracy measures overall correctness but can mislead with imbalanced data.

Precision answers “when I predict positive, am I usually right?” Critical when false positives are costly.

Recall answers “do I find most of the positives?” Essential when false negatives are expensive.

F1-Score balances precision and recall into a single metric.

AUC evaluates ranking quality across all thresholds, robust to class imbalance.

RMSE measures average prediction error with penalty for large mistakes.

R² indicates how much variance your model explains.

Choosing appropriate metrics requires understanding your problem, business constraints, and what success actually means. A 95% accurate model might be terrible if it misses 80% of the rare positive class you care about. An 85% accurate model might be excellent if it achieves this with perfectly balanced precision and recall.

The key lessons for effective metric use:

Match metrics to goals: Choose metrics that align with business objectives.

Use multiple metrics: Single metrics have blind spots.

Understand tradeoffs: Know what you’re optimizing for and what you’re sacrificing.

Consider context: Class balance, error costs, domain requirements all matter.

Report honestly: Include confidence intervals and multiple perspectives.

Monitor continuously: Metrics in development may differ from production.

As you build and evaluate machine learning systems, treat metric selection as a critical design decision, not an afterthought. The metrics you choose shape what your models optimize for, what gets deployed, and ultimately what value your machine learning systems deliver.

Master evaluation metrics, and you’ve mastered the language of machine learning performance—the ability to objectively assess, compare, and optimize models. This foundation enables you to make data-driven decisions, communicate effectively about model performance, and build systems that actually work when deployed to solve real problems.