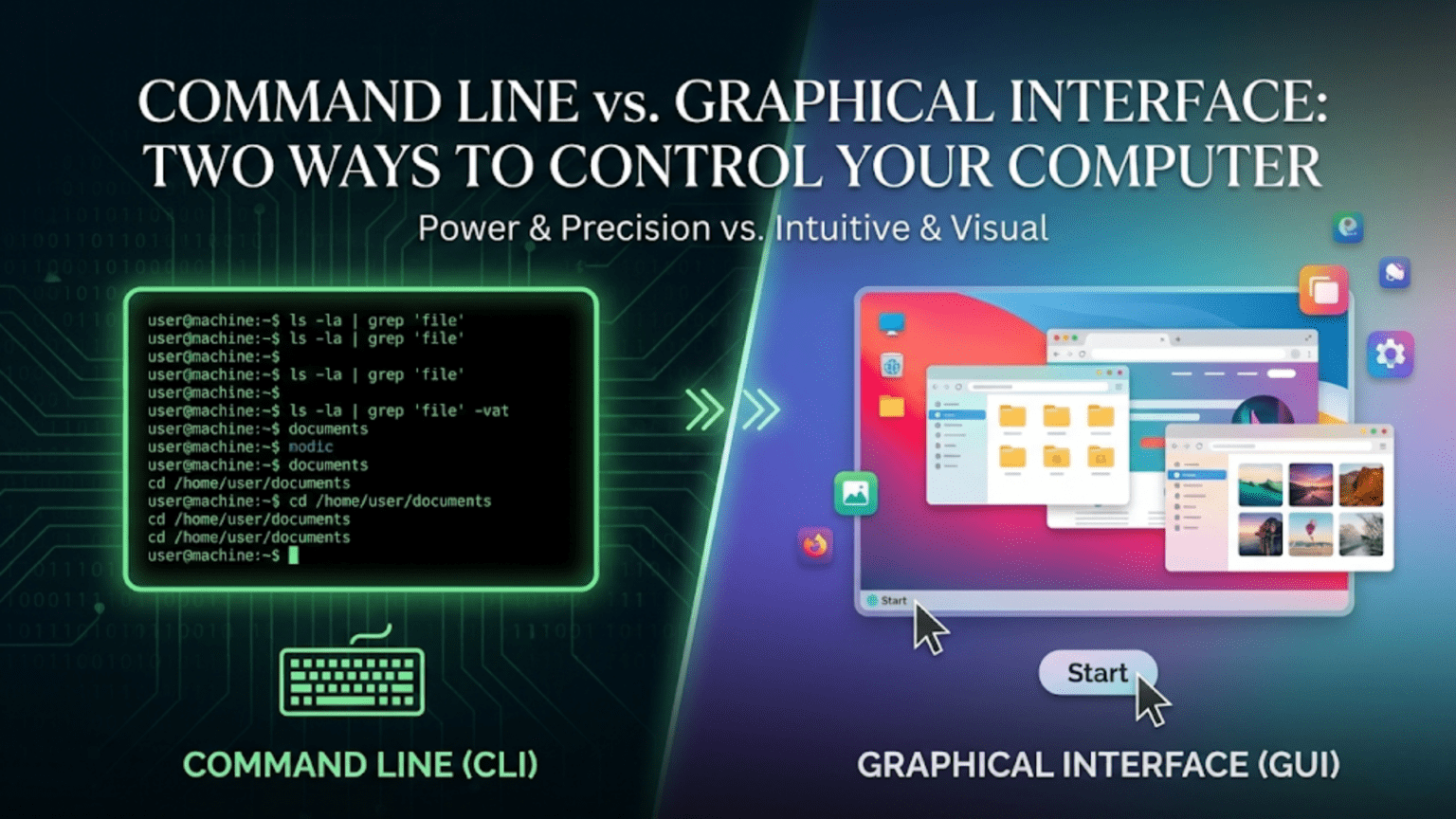

Understanding the Fundamental Approaches to Human-Computer Interaction

Every computer requires an interface—a means by which humans communicate their intentions to the machine and receive information back. For most people, this interface consists of visual elements they can see and click: windows, icons, buttons, and menus displayed on a screen and controlled with a mouse or touchscreen. This graphical approach feels intuitive and accessible, allowing users to accomplish tasks without memorizing complex commands or syntax. However, beneath this friendly surface lies an older, more direct way of communicating with computers: the command-line interface, where users type text commands and receive text responses, engaging in what feels like a conversation with the operating system itself.

These two paradigms—graphical and command-line interfaces—represent fundamentally different philosophies about how humans should interact with computers. Graphical interfaces prioritize discoverability, visual feedback, and gentle learning curves, making computers accessible to people with no technical training. Command-line interfaces prioritize efficiency, precision, and scriptability, offering power users and administrators capabilities that graphical interfaces struggle to match. Understanding both approaches, their respective strengths and weaknesses, and when each is appropriate provides a deeper appreciation for computer design and makes you a more capable user.

The relationship between these interface types is not adversarial—they’re complementary tools, each excelling at different tasks. Modern operating systems provide both, recognizing that some operations benefit from visual, interactive graphical interfaces while others work better with precise text commands. Professional users often seamlessly move between both interfaces throughout their workday, choosing the tool that best fits each situation. The most effective computer users understand both paradigms and can leverage whichever approach makes their current task easier, faster, or more reliable.

The Command Line: Direct Communication with the Operating System

Command-line interfaces present users with a text prompt—typically showing the current directory and a cursor awaiting input. Users type commands consisting of a program name, arguments specifying what the program should act upon, and options modifying the program’s behavior. The system executes the command, displays text output (if any), and presents another prompt. This cycle continues indefinitely, with users entering commands and receiving results in a text-based conversation with the operating system.

The directness of command-line interaction appeals to those who appreciate efficiency and precision. When you know exactly what you want to accomplish, typing a command can be substantially faster than navigating through multiple menus and dialog boxes. Consider copying a hundred files matching a specific pattern from various subdirectories into a new location—a graphical file manager would require navigating to each source location, selecting appropriate files, and copying them individually or in small groups. A single command line could express this operation concisely: find . -name "*.txt" -mtime -7 -exec cp {} /destination/ \; (this finds all .txt files modified in the last 7 days and copies them to the destination). The command is cryptic to the uninitiated but remarkably powerful once understood.

Command-line interfaces excel at automation through scripting. Any sequence of commands can be saved in a script file and executed repeatedly, identically each time. This capability enables system administrators to automate routine maintenance, developers to automate build processes, and power users to automate repetitive tasks. Scripts can include logic—conditional statements, loops, error handling—transforming simple command sequences into sophisticated programs. This programmability makes command lines immensely powerful for tasks requiring consistency, repetition, or complex workflows.

Command composition through pipes represents one of the command line’s most elegant features. The output of one command can feed directly as input to another command, creating processing pipelines that accomplish complex tasks by combining simple, focused tools. For example, ps aux | grep chrome | wc -l lists all running processes, filters for those containing “chrome,” and counts how many remain—telling you how many Chrome processes are running. Each command performs one specific task well, and piping them together creates new capabilities without writing custom programs.

Remote administration over network connections strongly favors command-line interfaces. Text commands require minimal bandwidth—a few bytes per command—while graphical interfaces need to transmit screen updates, mouse movements, and graphical elements, consuming vastly more bandwidth. Over slow or unreliable connections, command-line SSH sessions remain responsive while graphical remote desktop becomes unusable. For managing servers in data centers or cloud instances, command lines often represent the only practical interface.

However, command lines present significant barriers to entry. Learning requires memorizing commands, their options, and proper syntax. Different operating systems use different command sets—Linux commands differ from Windows commands, creating fragmentation. Commands fail with error messages that often don’t clearly explain the problem or solution. There’s no browsing or discovery mechanism—you must know what you’re looking for or consult documentation. For occasional users or those uncomfortable with text-based interaction, command lines feel intimidating and impenetrable.

The cognitive load of command-line interaction is substantial. You must remember command names, understand their options, mentally model how they’ll interact with the file system or system state, and predict their effects before execution. Mistakes can have serious consequences—a mistyped command might delete files you didn’t intend to remove. While modern shells include safety features and undo capabilities, command lines demand careful attention and understanding of what you’re doing.

Graphical Interfaces: Visual Computing for Everyone

Graphical user interfaces transform abstract computational operations into visual, manipulable objects. Files appear as icons that you can click to open or drag to move. Folders are visual containers you can browse hierarchically. Programs present controls—buttons, menus, sliders—that explicitly show available actions. Everything is designed for discoverability: you can explore the interface, try options, and learn through experimentation without necessarily consulting documentation.

The primary advantage of graphical interfaces is their accessibility to non-technical users. Someone who has never used a computer can learn basic operations relatively quickly because the interface leverages familiar metaphors and visual understanding. The desktop metaphor presents computing in terms of physical desks with documents and folders. Trash cans receive deleted files. Visual representations connect to existing mental models, reducing the conceptual gap between human intention and computer action.

Graphical interfaces provide immediate visual feedback confirming that actions have been received and executed. Click a button and it depresses, confirming the click registered. Drag a file and it moves with your cursor, showing the drag operation is happening. Progress bars indicate lengthy operations are proceeding. This constant feedback creates confidence that the system is responding appropriately, reducing uncertainty and anxiety.

For many common tasks—writing documents, editing images, browsing the web, managing email—graphical interfaces are clearly superior to command lines. These activities are inherently visual and interactive, benefiting from WYSIWYG displays and direct manipulation. Trying to edit a photograph through command-line utilities would be absurd when graphical image editors provide intuitive visual control. Similarly, arranging a page layout or composing a presentation naturally suit graphical approaches.

Graphical interfaces also excel at presenting complex information visually. Charts, graphs, diagrams, and other visualizations communicate patterns and relationships that would be difficult to convey through text. File browsers can show thumbnails of images, allowing visual identification. System monitors display resource usage graphically, making trends immediately apparent. These visual presentations leverage human visual processing capabilities, often conveying information faster than text equivalents.

However, graphical interfaces have limitations and disadvantages. They can be slower for experienced users performing routine tasks—navigating menus and clicking through dialog boxes takes more time than typing known commands. They consume more system resources—rendering graphics, handling mouse input, and updating displays requires more processing power and memory than text interfaces. They’re difficult to automate—while some graphical applications support scripting, many don’t, making repetitive tasks tedious.

Graphical interfaces can also hide underlying complexity, which is both a feature and a bug. Abstraction makes computing accessible but can leave users without understanding of what’s actually happening. When graphical tools fail or encounter edge cases, users often lack the knowledge to diagnose or fix problems because they’ve never seen the underlying mechanisms. This abstraction gap can create learned helplessness—dependence on graphical tools without understanding of alternatives.

When to Use Each Interface: Practical Guidance

Choosing between command-line and graphical interfaces depends on the task, your skill level, frequency of the operation, and available tools. Understanding these factors helps select the appropriate interface for each situation.

For one-time interactive tasks, graphical interfaces usually win. If you’re editing a single document, adjusting a photo, or configuring an application you use rarely, the graphical interface’s discoverability and visual feedback outweigh the command line’s efficiency advantages. The time spent looking up command syntax exceeds the time saved by using commands.

For repetitive operations, command lines excel. If you need to resize fifty images, rename a hundred files following a pattern, or perform the same database query repeatedly with different parameters, command lines enable automation that graphical interfaces can’t match. Write a script once, run it as many times as needed. The initial investment in learning commands pays dividends through time saved on repetition.

For remote administration, command lines are often essential. Managing servers, cloud instances, or remote systems typically happens through command-line SSH sessions because they work reliably over network connections and require minimal bandwidth. While graphical remote desktop exists, it’s often slower and less reliable than command-line alternatives for administrative tasks.

For system administration and configuration, professionals typically prefer command lines because they provide direct access to system internals, precise control over configurations, ability to script and automate tasks, and work consistently across different systems. Graphical configuration tools sometimes obscure important details or lack options for advanced settings that command lines expose.

For learning and understanding, command lines provide transparency into how systems work. Commands explicitly show what’s happening—copying files, changing permissions, installing packages—making the operation’s mechanics visible. This visibility aids understanding of system behavior. Graphical tools hide these details behind abstractions, which is friendly for novices but limits deeper learning.

For accessibility considerations, graphical interfaces generally work better for users with certain disabilities. Screen magnifiers work well with GUIs. Touch interfaces accommodate users with limited fine motor control. However, command lines can be superior for blind users with screen readers because text is inherently more screen-reader-friendly than complex graphical layouts. Accessibility is nuanced and depends on specific user needs.

For collaboration and documentation, both interfaces have advantages. Command lines produce explicit, text-based records of what was done—scripts and command histories document procedures. These records are easily shared, versioned, and reviewed. Graphical operations are harder to document precisely—screenshots help but don’t capture the full sequence of interactions. However, graphical interfaces can be easier to teach to others through demonstration and visual guides.

The Power of Combining Both Approaches

Modern computing environments recognize that both interface types have value and increasingly provide ways to combine their strengths.

Graphical terminals embed command-line interfaces within graphical environments. Terminal emulators on Linux, Terminal on macOS, and PowerShell or Command Prompt on Windows provide command-line access within the graphical desktop. Users can seamlessly switch between graphical applications and command-line terminals, using whichever interface suits each task. This integration makes both approaches accessible without requiring mode switching or different systems.

Many graphical applications expose command-line options or scripting interfaces, enabling automation of graphical programs. Photoshop supports scripting, allowing batch processing of images with programmatic control. Many IDEs integrate terminal access, letting developers use graphical editing while running build commands. This hybrid approach provides graphical convenience for interactive work and command-line power for automation.

File managers often integrate terminal access, allowing you to open a command line in the current directory. Conversely, some command-line tools can launch graphical applications for specific tasks. This bidirectional integration recognizes that users often need both approaches and facilitates smooth transitions between them.

Modern shells enhance command lines with graphical features while maintaining text-based interaction. Syntax highlighting colors commands, arguments, and options differently, improving readability. Autocomplete suggests commands and arguments, reducing memorization requirements. Graphical shell prompts show git status, system load, or other information visually. These enhancements make command lines more accessible without sacrificing their fundamental advantages.

Learning the Command Line: Getting Started

For users familiar only with graphical interfaces, the command line seems daunting. However, learning a few fundamental concepts and commands opens up powerful capabilities.

Understanding basic command structure helps demystify command lines. Commands typically follow the pattern: command options arguments. The command specifies what program to run. Options modify the command’s behavior, usually preceded by dashes (like -l or --verbose). Arguments specify what to operate on—files, directories, or other data. For example, ls -la /home lists (ls) with long format (-l) and showing hidden files (-a) the /home directory.

Navigation commands form the foundation of command-line usage. pwd shows the current directory (print working directory). cd changes directories (cd /home/user/documents). ls lists directory contents. These three commands enable basic file system navigation—knowing where you are, moving to different locations, and seeing what’s available.

File manipulation commands handle common operations. cp copies files, mv moves or renames them, rm removes them (carefully—there’s no trash!), mkdir creates directories, and touch creates empty files. These commands, combined with navigation, handle most basic file operations.

Viewing file contents uses commands like cat (display entire file), less or more (view file page by page), head (show first lines), and tail (show last lines). These tools let you examine files without opening them in editors, useful for quick inspections or viewing log files.

Getting help is essential for learning. Most commands support a --help option showing usage information: ls --help. Man pages (manual pages) provide detailed documentation: man ls. These resources explain command options and usage, making commands self-documenting once you know to consult them.

Practice in safe environments reduces fear of mistakes. Create a test directory with sample files where mistakes don’t matter. Experiment with commands, observe their effects, and develop understanding through hands-on experience. Virtual machines provide even safer practice environments where you can’t damage your main system.

Advanced Command-Line Concepts

Beyond basic commands, several advanced concepts unlock the command line’s full power.

Pipes and redirection enable command composition. The pipe symbol (|) sends one command’s output as input to another: cat file.txt | grep "error" | sort. Redirection symbols (>, >>, <) send output to files or read input from files: ls > directory-listing.txt saves the listing to a file. These operators turn simple commands into sophisticated processing pipelines.

Variables store information for later use. Environment variables like PATH (directories to search for commands) and HOME (user’s home directory) control system behavior. Shell variables store data within scripts. Understanding variables helps with script writing and system configuration.

Command substitution runs a command and uses its output: echo "Today is $(date)" executes the date command and inserts its output into the echo statement. This capability allows dynamic script content based on command results.

Aliases create shortcuts for frequently used commands: alias ll='ls -la' creates ll as a short way to run ls -la. Aliases reduce typing for common operations and can set default options for commands.

Job control manages multiple processes from one terminal. Running commands in the background (command &), suspending running commands (Ctrl+Z), and bringing background jobs to foreground (fg) enable multitasking within a single terminal session.

Regular expressions provide powerful pattern matching for searching and manipulating text. While complex, regex enables operations that would be tedious or impossible otherwise. Commands like grep, sed, and awk use regex for sophisticated text processing.

Graphical Shells: Bridging the Gap

Some interfaces attempt to provide command-line power with graphical discoverability. These graphical shells or command builders help users transition between paradigms.

Command builders present graphical forms for constructing commands. Users select options from dropdowns, check boxes, and fill in fields. The interface builds the corresponding command, which users can execute immediately or save for later use. This approach teaches command syntax while providing graphical convenience—users see how their selections translate to text commands.

Visual pipeline builders let users construct processing pipelines graphically by connecting blocks representing commands. Each block’s input and output connectors show data flow. The system translates the visual representation to actual commands. This graphical approach to pipeline construction helps users understand command composition without memorizing pipe syntax.

Integrated development environments (IDEs) provide graphical interfaces for programming but integrate terminal access seamlessly. Developers can use graphical tools for editing, debugging, and project management while accessing command-line tools for version control, building, and deployment. This integration recognizes that modern development benefits from both paradigms.

File managers with command-line integration show both views simultaneously. A graphical file browser occupies part of the window while a terminal showing commands occupies another part. Users can perform operations in either interface, with both views staying synchronized. This dual presentation helps users understand how graphical operations correspond to commands.

The Future: Voice, Gesture, and Natural Language

Interface evolution continues beyond traditional command lines and GUIs, though these paradigms remain foundational.

Natural language interfaces attempt to bridge the gap between human language and computer commands. Instead of memorizing syntax, users express intentions in plain language: “show me all photos from last month.” The system interprets this natural language and executes appropriate commands. While promising, natural language introduces ambiguity—computers struggle with the vagueness and context-dependence inherent in human language. Natural language works well for simple, common operations but becomes unwieldy for complex or precise tasks where command-line precision or graphical directness remains superior.

Voice interfaces enable hands-free interaction through spoken commands. Digital assistants on phones and smart speakers demonstrate voice control’s viability for many tasks. However, voice has limitations: it lacks precision for many operations, provides no visual feedback showing available options, requires quiet environments for reliable recognition, and can be slower than typing for experienced users. Voice complements rather than replaces traditional interfaces.

Gesture control allows interaction through hand or body movements detected by cameras. Gaming systems pioneered gesture interfaces, and they’re expanding to other contexts. Gestures work well for spatial operations—rotating 3D models, navigating virtual environments—but struggle with precise selection or text entry. Like voice, gestures complement traditional interfaces for specific use cases rather than replacing them.

Augmented and virtual reality experiment with three-dimensional interfaces that abandon the desktop metaphor entirely. Users interact with virtual objects in 3D space through controllers or hand tracking. These interfaces excel at spatial tasks but currently lack efficiency for text-heavy work or complex data manipulation. As the technology matures, AR/VR may develop new interaction paradigms, though text and visual interfaces will likely persist for many tasks.

Making Peace with Both Paradigms

The command-line versus graphical interface comparison isn’t about determining which is superior—both have legitimate strengths making them appropriate for different contexts. The most capable users understand both paradigms and choose appropriately based on the task at hand.

For beginners, starting with graphical interfaces makes sense. They’re more accessible, less intimidating, and enable productivity with minimal training. As you become comfortable with basic computing, gradually exploring command-line capabilities expands your skill set and makes you more versatile. You don’t need to abandon graphical interfaces—simply add command-line tools to your repertoire.

For advanced users comfortable with command lines, remember that graphical interfaces aren’t just for beginners. Complex visualizations, interactive design work, and many other tasks genuinely work better with graphical approaches. Using whichever interface best fits each task demonstrates wisdom, not weakness.

The richness of modern computing environments lies partly in supporting multiple interaction paradigms. Operating systems that provide both excellent graphical interfaces and powerful command-line access enable users to work effectively regardless of their preferences or the task’s requirements. Appreciating both approaches, understanding their respective strengths, and developing skills in each creates computing versatility that purely graphical or purely command-line users lack.

Next time you face a computing task, consciously consider which interface would work best. Simple, one-time operations? Probably graphical. Repetitive operations affecting many files? Consider the command line. Need to understand exactly what’s happening? Command line shows you explicitly. Working with visual content? Graphical wins. Over time, these decisions become intuitive, and you’ll find yourself seamlessly moving between interfaces, leveraging the strengths of each to work more effectively than either approach alone could provide.

The command line and graphical interface represent different philosophies of human-computer interaction, each reflecting deep insights about usability, efficiency, and the nature of computing itself. Understanding both enriches your relationship with technology and empowers you to use computers more effectively, whether you’re writing your first document or administering thousands of servers. The computer ultimately doesn’t care which interface you use—it’s simply waiting for your instructions, ready to respond whether they come as mouse clicks or typed commands.