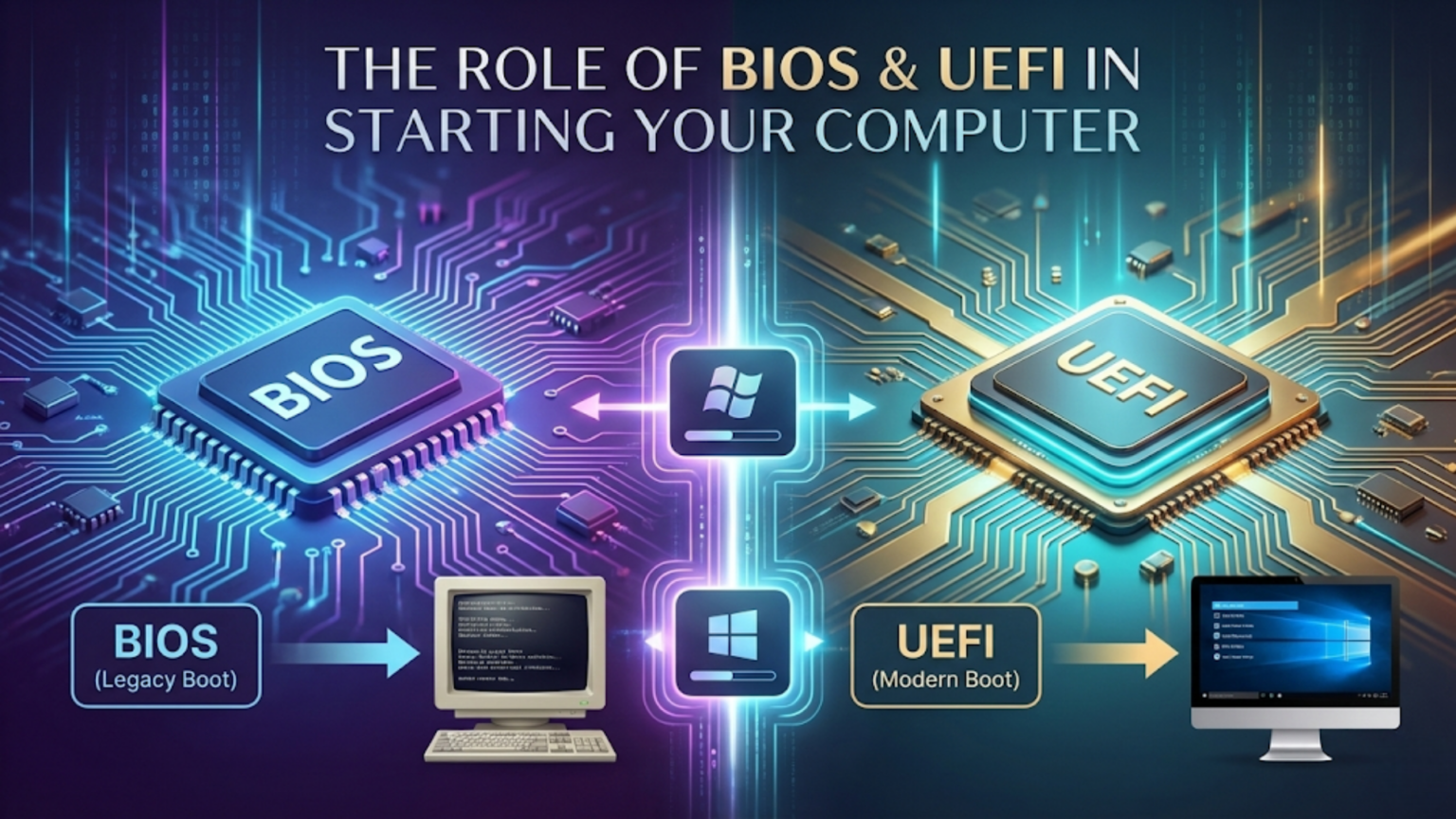

Understanding the Firmware Bridge Between Hardware and Operating System

Before your operating system can take control of your computer, before any familiar startup screens appear, before the boot process even truly begins, a critical piece of software springs into action the instant electrical power reaches your motherboard. This software, called firmware, represents the deepest layer of code in your computer—software that’s permanently stored in chips on the motherboard itself, surviving power loss and remaining present even when no operating system is installed. The two dominant firmware standards, BIOS and its modern successor UEFI, serve as the essential bridge between raw hardware and the operating system, performing hardware initialization, conducting system tests, and ultimately transferring control to the bootloader that will launch your OS.

Understanding BIOS and UEFI reveals the foundation upon which all computing builds. These firmware systems exist in a unique position: they’re software, yet they’re embedded in hardware. They run before any operating system loads, yet they provide services that operating systems use. They’re invisible during normal operation, yet they’re absolutely essential. When you press the power button, firmware is the first software that executes, and its successful operation determines whether your computer can boot at all. Problems at the firmware level can prevent booting entirely, leaving you with a seemingly dead computer despite potentially having perfectly functional hardware and a valid operating system.

The evolution from traditional BIOS to modern UEFI represents one of the most significant transitions in PC architecture in decades, comparable to the shift from 16-bit to 32-bit computing. This transition addressed fundamental limitations that had accumulated over thirty years of BIOS use while introducing capabilities that enable modern security features, faster booting, and support for contemporary hardware. Yet despite UEFI’s advantages, BIOS systems remain in use on billions of older computers, and understanding both technologies helps explain various boot-related behaviors, troubleshooting scenarios, and compatibility considerations.

What is BIOS? The Traditional Firmware Standard

BIOS, which stands for Basic Input/Output System, originated in the 1970s as a way to provide a hardware abstraction layer for early personal computers. The concept was standardized for IBM PC-compatible computers in the early 1980s and remained largely unchanged for over thirty years—a remarkable longevity in the rapidly evolving computer industry. This longevity speaks both to BIOS’s utility and to the power of backward compatibility in the PC ecosystem.

At its core, BIOS is a small program stored in a flash memory chip on the motherboard—typically just a few megabytes. When you power on the computer, the processor begins executing instructions from a predefined memory address that maps to the BIOS chip. This execution happens automatically due to how the processor is designed; it doesn’t need any prior configuration or loading—the BIOS code is simply there, hardwired into the system’s memory map.

The BIOS’s first responsibility is conducting the Power-On Self-Test (POST), a series of diagnostic checks that verify essential hardware is present and functioning. POST tests the processor itself, checks that memory is installed and working, verifies that the keyboard controller responds, confirms video hardware is present, and examines other critical components. During POST, you might see memory counting up on screen or brief text messages indicating what’s being tested. If POST detects a problem, the BIOS typically emits a series of beeps through the computer’s speaker—beep codes that indicate which component failed. These codes vary by BIOS manufacturer but provide valuable diagnostic information when the system can’t display errors on screen.

After POST completes successfully, BIOS initializes hardware to a basic operational state. It configures memory controllers so the CPU can access RAM, sets up interrupt controllers so devices can signal the processor, initializes display adapters enough to show basic text output, and prepares storage controllers to access drives. These initializations are minimal—just enough to allow the next stage of booting to proceed. The operating system will later reconfigure hardware more thoroughly, but BIOS provides the foundation that makes this possible.

BIOS provides a set of basic input/output routines—the “services” that give BIOS its name. These routines allow programs to perform simple operations without knowing hardware specifics: reading from or writing to the disk, displaying characters on screen, reading keyboard input, and accessing other basic functions. Early operating systems and bootloaders relied heavily on these BIOS services. Modern operating systems largely bypass BIOS services in favor of their own drivers, but they’re still crucial during the early boot process when the OS’s drivers aren’t yet loaded.

The BIOS setup utility—accessed by pressing a specific key during startup, commonly Delete, F2, or F10—allows configuring system settings. This text-mode interface lets you set the boot device order (which drives the system tries to boot from), enable or disable hardware components, configure processor and memory timings, set system date and time, and adjust numerous other parameters. These settings are stored in a small amount of battery-backed CMOS memory—typically just a few hundred bytes—that retains settings even when the computer is powered off. When the CMOS battery dies, the system loses these settings and reverts to defaults, often causing boot problems until the battery is replaced.

BIOS uses the Master Boot Record (MBR) partitioning scheme for hard drives. The MBR resides in the first sector of the disk—just 512 bytes—containing both a partition table describing how the disk is divided and a small boot program. When BIOS decides to boot from a disk, it loads this 512-byte sector into memory and executes the boot program it contains. This program is so limited by size constraints that it typically can do little more than load a larger, more capable bootloader from elsewhere on the disk.

BIOS Limitations and Why UEFI Was Needed

Despite its long service, BIOS accumulated serious limitations that increasingly constrained modern computing. These limitations weren’t just minor inconveniences—they fundamentally restricted what computers could do and how they could be secured.

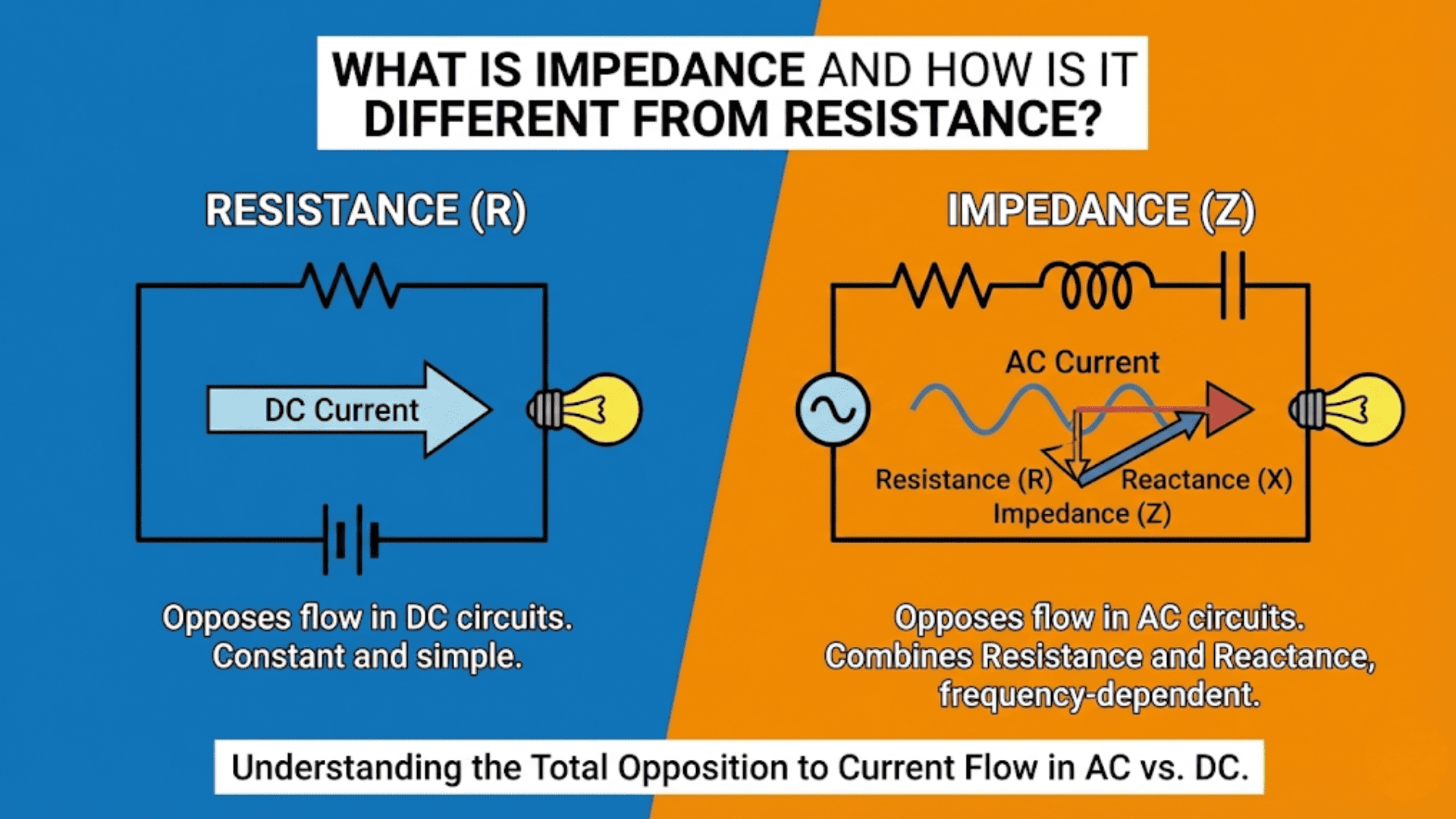

The 16-bit real mode limitation represented BIOS’s most fundamental constraint. BIOS code runs in 16-bit real mode, a processor mode from the original 8086 processors of the early 1980s. Real mode limits memory access to one megabyte and lacks memory protection or privilege levels. Modern processors are vastly more capable—64-bit with gigabytes of addressable memory and sophisticated protection mechanisms—but BIOS forces them to start in this ancient mode. Operating system bootloaders must then transition from 16-bit real mode through 32-bit protected mode to finally reach 64-bit long mode, a cumbersome process that adds complexity and time to booting.

The MBR partitioning scheme’s 512-byte boot sector severely limited what initialization code could accomplish. More significantly, MBR limited disks to 2 terabytes maximum size and supported only four primary partitions. These restrictions became increasingly problematic as storage capacities grew. Working around the partition limit required extended partitions—a complex scheme where one primary partition contains logical partitions—that added complexity without truly solving the underlying limitation.

BIOS configuration storage in tiny CMOS memory meant extremely limited settings could be saved—typically just a few hundred bytes total. This constraint restricted what options could be offered and how much information could be stored about system configuration. Modern hardware with numerous configurable options couldn’t expose all their settings through BIOS.

Security represented perhaps BIOS’s most glaring deficiency. BIOS had essentially no security features. Anyone with physical access could modify BIOS settings, replace the BIOS chip, or inject malicious code into the boot process. The Master Boot Record could be easily infected with bootkits—malware that loads before the operating system and could therefore completely control the system while hiding from detection. Operating systems tried to implement security measures, but they were fundamentally undermined by the insecure foundation BIOS provided.

The BIOS interface—text-mode only with keyboard-only navigation—was increasingly antiquated. Users expected graphical interfaces with mouse support, but BIOS’s limitations made sophisticated interfaces impractical. Configuration was confusing, options were cryptically named, and helpful documentation was scarce within the interface itself.

Extension mechanisms for device-specific firmware (option ROMs) were limited and problematic. Video cards, RAID controllers, and network adapters often needed to provide their own initialization code. BIOS allocated specific memory regions for these option ROMs, but the limited space available and primitive loading mechanisms caused conflicts and complexity.

UEFI: The Modern Firmware Replacement

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) was developed in the late 1990s by Intel as EFI for their Itanium systems, later evolving into UEFI as an industry-wide standard. Modern computers manufactured since the mid-2010s predominantly use UEFI, though most support a BIOS compatibility mode for older operating systems.

UEFI represents a complete reimagining of firmware rather than an incremental improvement. It runs in 32-bit or 64-bit mode from the start, immediately accessing gigabytes of memory with full processor capabilities. This modern environment allows UEFI firmware to be substantially more sophisticated than BIOS ever could be. Where BIOS might be a few hundred kilobytes, UEFI firmware commonly measures several megabytes, containing far more features and capabilities.

The UEFI firmware includes a complete pre-boot environment with services and drivers. Device drivers for storage controllers, network adapters, and other hardware operate within this environment, providing standardized interfaces. UEFI applications can run before the operating system loads—diagnostic utilities, recovery tools, firmware updates, and even web browsers or games. This pre-boot environment creates possibilities that simply don’t exist in BIOS systems.

The GUID Partition Table (GPT) replaces MBR, addressing its major limitations. GPT supports disks up to 9.4 zettabytes (billions of terabytes), effectively unlimited for any foreseeable future. It supports 128 partitions by default without complex extended partition schemes. GPT stores partition information redundantly in multiple locations, providing better data integrity than MBR’s single point of failure. Each partition has a globally unique identifier (GUID) and can include a human-readable name.

The EFI System Partition (ESP) provides a dedicated FAT32-formatted partition where bootloaders and boot-related files reside. Unlike MBR’s 512-byte boot sector, the ESP can contain complete bootloader applications. Each operating system installs its bootloader as a file in the ESP, and UEFI maintains a boot menu listing available boot options. This design eliminates the need for bootloaders to chain-load each other and simplifies multi-boot configurations.

UEFI’s graphical capabilities enable modern, user-friendly interfaces. UEFI setup utilities can use high-resolution graphics, mouse input, and intuitive layouts. Some implementations include web browsers, network configuration tools, and sophisticated diagnostic utilities. While not all UEFI implementations take full advantage of these capabilities—some still use text-mode interfaces similar to BIOS—the potential exists for far more usable firmware interfaces.

Secure Boot, one of UEFI’s most important features, addresses BIOS’s security deficiencies. Secure Boot uses digital signatures to verify that bootloader code comes from trusted sources and hasn’t been tampered with. The firmware maintains a database of trusted signing keys and refuses to execute unsigned or improperly signed code. This prevents bootkits and other firmware-level malware from loading, significantly strengthening system security. While Secure Boot has generated controversy—particularly regarding its implications for Linux and other alternative operating systems—it provides substantial security benefits when properly implemented.

Network booting capabilities built into UEFI allow computers to boot operating systems from network servers without local storage. The firmware includes network drivers and can implement the Preboot Execution Environment (PXE), essential for large-scale deployments, diskless workstations, and enterprise management scenarios.

UEFI stores configuration in NVRAM (non-volatile random-access memory) rather than battery-backed CMOS, providing substantially more storage space—typically several megabytes versus hundreds of bytes. This expansion allows comprehensive settings for modern hardware complexity while eliminating the CMOS battery dependency that plagued BIOS systems.

Secure Boot: Understanding UEFI’s Security Feature

Secure Boot deserves detailed attention as it represents UEFI’s most significant security advancement and has generated considerable technical and political discussion in the computing community.

The security problem Secure Boot solves is fundamental: how can the system trust that the software it’s about to execute is legitimate? Traditional BIOS had no way to verify bootloader authenticity. Malware authors exploited this by creating bootkits that infected the Master Boot Record or other boot components, loading before the operating system and gaining complete system control. These infections were notoriously difficult to detect and remove because the malware controlled the system from its foundation.

Secure Boot implements a chain of trust using public key cryptography. The UEFI firmware contains public keys for trusted signing authorities—typically Microsoft, hardware manufacturers, and sometimes Linux distributions. Bootloaders and other code that runs during boot must be digitally signed with the corresponding private keys. When UEFI loads a bootloader, it verifies the digital signature against its trusted key database. Only if the signature is valid and the code hasn’t been modified does execution proceed. Unsigned or improperly signed code is rejected, preventing untrusted software from running.

This verification process continues through the boot chain. The bootloader verifies the kernel’s signature before loading it. The kernel verifies driver signatures before loading them. Each component verifies the next, maintaining the chain of trust from firmware through to the fully loaded operating system. This defense-in-depth approach ensures that even if one layer is compromised, subsequent layers can detect the breach.

The key management aspect of Secure Boot has proven controversial. By default, most UEFI systems trust Microsoft’s keys since Windows requires Secure Boot. Linux distributions must either obtain Microsoft signatures for their bootloaders (which costs money and requires Microsoft approval) or have users manually add Linux signing keys to their firmware’s trust database. This situation has created tension between security goals and open platform principles.

Most UEFI implementations allow users to disable Secure Boot or manage the key database manually. You can add custom keys, remove existing keys, or disable verification entirely. This flexibility is essential for alternative operating systems, development scenarios, or situations where Secure Boot causes compatibility issues. However, disabling Secure Boot eliminates its security benefits, requiring users to balance security against compatibility.

Some criticisms of Secure Boot focus on its implementation rather than the concept. Ideally, users would control their own computers’ trust decisions, but the default configuration trusts Microsoft implicitly. Some argue this gives Microsoft too much control over what can run on hardware users own. Others counter that default trust in a well-established authority provides better security for non-technical users than expecting them to manage cryptographic keys.

Despite controversies, Secure Boot provides genuine security benefits when properly configured. It prevents a significant class of attacks that were previously difficult to defend against. Modern malware that attempts to persist at the firmware level is blocked. Users who understand the technology can maintain the security benefits while preserving the ability to run alternative operating systems by managing keys appropriately.

UEFI Boot Process: From Power-On to Operating System

Understanding the UEFI boot sequence reveals how modern computers start and helps explain what’s happening during those first seconds after pressing the power button.

Power-on initiates the Security (SEC) phase. The processor begins executing code from a specific memory address mapped to the UEFI firmware chip. This initial code performs the most basic processor initialization, establishes a minimal execution environment, and locates the rest of the firmware. This phase happens extremely quickly, typically completing in microseconds.

The Pre-EFI Initialization (PEI) phase follows, conducting hardware initialization similar to BIOS POST but more comprehensive. UEFI examines the system to discover installed hardware, initializes memory controllers and tests RAM, sets up the processor cache as temporary memory before RAM is available, and creates data structures describing the hardware configuration. PEI modules can be supplied by hardware vendors to support specific components, allowing UEFI to properly initialize diverse hardware without the main firmware needing device-specific knowledge.

The Driver Execution Environment (DXE) phase creates the main UEFI environment. DXE loads device drivers provided by the firmware or hardware, establishes system services that bootloaders can use, creates protocol interfaces for accessing hardware, and prepares the system for running UEFI applications. This phase constitutes the bulk of UEFI’s functionality, transforming the minimal PEI environment into a capable pre-boot operating environment. DXE is where UEFI’s sophistication becomes apparent—numerous drivers and services load, preparing the system for the next stage.

Boot Device Selection (BDS) determines what to boot. UEFI examines its boot configuration variables stored in NVRAM, listing boot options in priority order. It looks for the EFI System Partition on configured boot devices, searches for bootloader applications in the ESP, and presents a boot menu if configured to do so. The boot manager can intelligently handle boot failures, trying alternative boot options if the first choice fails. Users can interrupt this process to access the boot menu or firmware setup utility.

Runtime (RT) services remain available after the operating system loads. Unlike BIOS which becomes irrelevant once the OS takes over, UEFI continues providing services that operating systems use. These runtime services allow the OS to access NVRAM variables, read the system clock, reset the system, and update firmware. This persistent availability enables features like firmware updates from within the operating system without requiring separate utilities or procedures.

The handoff to the operating system occurs when UEFI loads and executes the selected bootloader. The bootloader is a UEFI application—a standard executable file that can use UEFI services to locate and load the operating system kernel. Windows Boot Manager, GRUB for Linux, or other bootloaders take control at this point. They use UEFI services to read configuration files, display boot menus, load kernel files, and eventually start the operating system. Once the OS takes control, UEFI transitions to providing only runtime services while the OS manages most system operations.

Compatibility Mode and Legacy Support

The transition from BIOS to UEFI raised practical questions: how could new UEFI systems run older operating systems expecting BIOS? How could users dual-boot between UEFI-aware and legacy operating systems? These concerns led to Compatibility Support Module (CSM) implementations.

CSM provides BIOS emulation within UEFI firmware. When enabled, CSM makes the UEFI system behave much like traditional BIOS, allowing older operating systems to install and boot normally. CSM intercepts calls that the old OS expects BIOS to handle and translates them to UEFI equivalents. This capability ensured smooth transition—users could gradually migrate from legacy operating systems without immediately replacing all their software.

However, CSM introduces complications. Systems with CSM enabled can boot in either UEFI native mode or legacy BIOS mode, but not both simultaneously. This creates potential for confusion: you might install an operating system in UEFI mode but configure the firmware to boot in legacy mode, resulting in an unbootable system. Boot media must be prepared for the correct mode—UEFI boot media won’t work in legacy mode and vice versa.

The legacy boot mode limitations carry over even on UEFI hardware. When operating in compatibility mode, the system uses MBR partitioning with its 2TB limit and four partition restriction. Secure Boot is disabled in legacy mode since it requires UEFI boot. The system sacrifices UEFI advantages to maintain backward compatibility.

Modern UEFI systems increasingly disable CSM by default or remove it entirely. Windows 11 requires UEFI and Secure Boot, refusing to install on legacy BIOS systems. Current Linux distributions strongly prefer UEFI installation. As older operating systems age out of use, CSM support becomes less critical and is being phased out. This simplifies firmware implementation and removes potential attack vectors, though it does eliminate the ability to run truly ancient operating systems on modern hardware.

Dual-booting between UEFI and legacy operating systems on the same computer is technically possible but complicated. The system must switch modes depending on which OS is booting, requiring careful configuration and understanding of boot processes. Most users are better served by choosing one mode and using only compatible operating systems.

Firmware Updates and Management

Unlike traditional software that loads from disk, firmware resides in chips on the motherboard, making updates a special process that carries risks. Understanding firmware update procedures and their implications helps users maintain systems safely.

Firmware updates address bugs, add hardware support, improve compatibility, enhance security, and sometimes add new features. Manufacturers release updates periodically, though not as frequently as operating system updates. Checking for firmware updates several times per year represents reasonable maintenance, more frequently if specific problems exist that updates might address.

The update process typically involves downloading a firmware image file from the manufacturer’s website, using a utility provided by the manufacturer to install it, and restarting the computer to apply the update. During the update, the system writes new firmware to the flash chip, replacing the old version. This process is sensitive—power loss or errors during update can “brick” the system, leaving it unable to boot. For this reason, firmware updates should only be performed with stable power and careful attention.

Some modern systems support firmware updates from within the operating system, using UEFI runtime services to safely update firmware without requiring special utilities or bootable media. Windows Update can deliver firmware updates for some systems. Linux utilities like fwupd provide similar capabilities. These OS-integrated update mechanisms are generally safer than traditional methods because they can verify updates, provide recovery options, and handle errors more gracefully.

Dual BIOS or firmware backup features on some motherboards maintain a second firmware copy. If the primary firmware becomes corrupted, the system automatically boots from the backup, allowing recovery. This feature provides insurance against failed updates, though it increases hardware cost and complexity.

Firmware downgrading—reverting to an older version—is sometimes necessary if a new version causes problems, but many systems prevent downgrading for security reasons. Older firmware might contain vulnerabilities that newer versions fixed, and allowing downgrading could enable attacks that exploit those vulnerabilities. Some systems allow downgrading only with special procedures or after disabling security features.

Security vulnerabilities in firmware are particularly serious because firmware operates at such a fundamental level. Vulnerabilities might allow attackers to install persistent malware that survives operating system reinstallation or to bypass security features like Secure Boot. Firmware security updates should be treated as critical and installed promptly. The Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities required firmware updates on most systems, demonstrating how even processor-level security issues require firmware patches.

Practical Implications: Why This Matters

Understanding BIOS and UEFI isn’t just academic—it has practical implications for everyday computer use, troubleshooting, and system configuration.

Boot problems often trace to firmware issues. If the system doesn’t start at all, the problem might be in POST—hardware failure that firmware detects. If the system starts but can’t find a boot device, firmware configuration might specify the wrong boot order. If boot fails with cryptic errors, the bootloader might be damaged or incompatible with the firmware mode. Understanding firmware’s role helps diagnose these issues systematically.

Installing operating systems requires awareness of firmware type and configuration. Modern operating systems prefer UEFI installation and may not support BIOS mode. Boot media must match the firmware mode—UEFI media for UEFI systems, legacy media for BIOS systems. Secure Boot might prevent booting some media, requiring temporary disabling. Installing with the wrong configuration creates problems that may not be obvious until later.

Hardware compatibility sometimes depends on firmware support. Some new hardware requires UEFI and doesn’t provide legacy BIOS support. Very old hardware might not have UEFI drivers available. Understanding firmware limitations helps predict whether hardware will work together.

Security features built into firmware—Secure Boot, TPM integration, firmware passwords—provide important protection but require understanding to use effectively. Misconfiguration can reduce security or make systems difficult to use. Proper configuration balances security against usability.

The firmware represents the deepest software layer in your computer, the foundation upon which everything else builds. Whether BIOS or UEFI, this firmware performs the critical task of bringing hardware to life, testing it, initializing it, and handing control to the operating system. Understanding these systems demystifies the early boot process, enables better troubleshooting, and provides insight into the architecture of modern computing. The next time you press that power button and your computer springs to life, you’ll appreciate the sophisticated firmware that makes it all possible.