Introduction

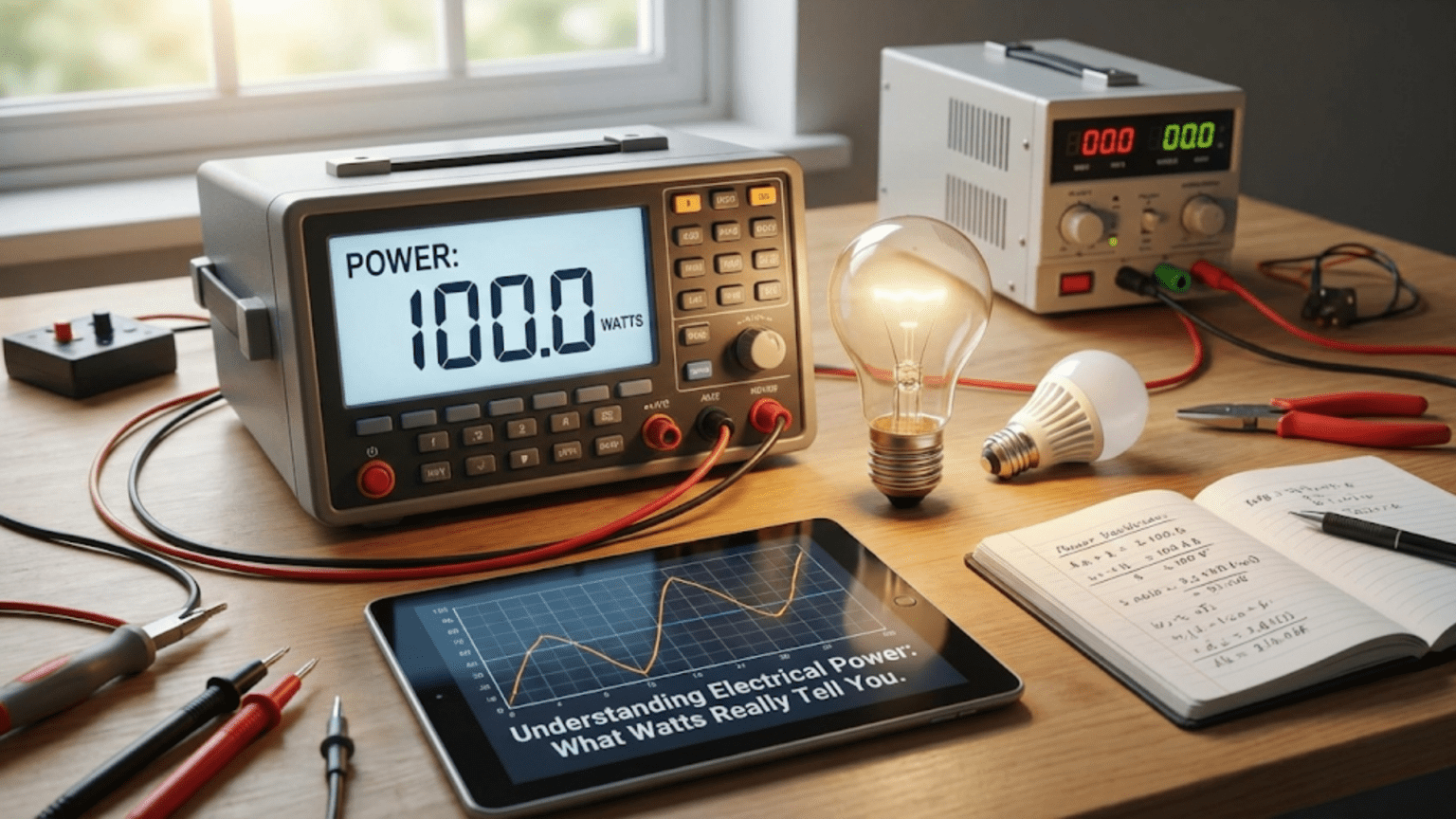

Power represents one of the most practical and immediately useful electrical concepts because it quantifies the rate at which electrical energy is consumed or delivered, directly connecting abstract electrical quantities to tangible real-world effects like brightness of light bulbs, heat output from heaters, running time of battery-powered devices, and electricity costs on monthly utility bills. While voltage measures electrical pressure and current measures flow rate, power combines both to indicate how much actual work electricity performs per unit time—whether that work is illuminating a room, spinning a motor, charging a battery, or running a computer. Understanding electrical power transforms electronics from abstract theory into practical knowledge about energy consumption, battery life, heat generation, and the capabilities and limitations of power supplies and components.

For beginners learning electronics, the watt—the standard unit of electrical power—appears everywhere from light bulb packages claiming forty watts or sixty watts through smartphone chargers rated for five watts or eighteen watts to household appliances consuming hundreds or thousands of watts. Yet what these numbers actually mean and how they relate to other electrical quantities often remains mysterious despite their ubiquity. A forty-watt light bulb produces less light than a sixty-watt bulb, but why? An eighteen-watt phone charger charges faster than a five-watt charger, but what makes it more powerful? A space heater consuming fifteen hundred watts dramatically increases your electricity bill while an LED bulb using nine watts barely registers—understanding these differences requires understanding electrical power.

The practical implications of understanding power extend far beyond reading appliance labels. When designing electronic circuits, power calculations determine whether components will overheat and fail, whether batteries will last hours or minutes, whether power supplies can deliver required current without overloading, and whether wiring will carry currents safely without excessive voltage drops or fire hazards. Underestimating power requirements causes components to burn out, batteries to deplete prematurely, or circuits to malfunction from inadequate supply voltages. Overestimating power requirements wastes money on oversized components and creates unnecessarily heavy or bulky designs. Accurate power calculations enable right-sizing components for reliable operation without waste.

The mathematical relationship between power, voltage, and current provides the foundation for all power calculations in DC circuits, with the simple equation power equals voltage times current—written mathematically as P equals V times I—capturing the essential relationship. This deceptively simple equation reveals that power increases when either voltage or current increases, and that for a given power level, high voltage operation uses less current than low voltage operation, explaining why power transmission uses high voltages to minimize current and thus resistive losses in wiring. Understanding how to apply this equation and its various rearrangements enables calculating power consumption, determining current requirements for known power loads, or finding voltages needed to deliver specified power.

This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of electrical power from fundamental concepts through practical applications, examining what power means physically, how the watt quantifies power, the mathematical relationships connecting power to voltage and current, power dissipation in resistors and how to prevent component overheating, power ratings on common components and what they mean, calculating power consumption in complete circuits, understanding efficiency and why not all consumed power does useful work, and practical power considerations for batteries, power supplies, and real-world circuit design. By the end, you will understand electrical power thoroughly enough to calculate power requirements for circuits, select components with adequate power ratings, estimate battery life, and understand your electricity bill and how electronics consume energy.

What Power Means: The Rate of Energy Transfer

Understanding power requires first understanding energy and the distinction between energy and the rate at which energy is used or transferred.

Energy Versus Power

Energy represents the capacity to do work—to move objects, generate heat, produce light, or cause any other physical change. Batteries store energy chemically, capacitors store energy in electric fields, springs store energy mechanically, and hot objects store thermal energy. When these stored energies are released, they can perform useful work like moving motors, lighting LEDs, or heating elements. The total amount of work that can be done depends on the total stored energy, measured in joules in the metric system or watt-hours and kilowatt-hours for electrical energy.

Power, distinct from energy, measures how quickly energy is transferred or converted from one form to another. A battery contains a fixed amount of energy, but the power delivered—how quickly that energy depletes—depends on the load connected to the battery. A bright LED consuming significant current drains battery energy rapidly, delivering high power, while a dim LED consuming little current drains the same battery slowly, delivering low power. Both LEDs eventually consume all the battery’s energy, but at different rates indicated by different power levels.

The analogy to water helps clarify this distinction. A water tower stores a fixed quantity of water representing energy, while the rate at which water flows from the tower through a pipe represents power. A large pipe allows rapid flow delivering high power, quickly depleting the stored water. A small pipe restricts flow to low power, slowly depleting the same stored quantity. The total work performed—perhaps filling a swimming pool—depends on total water volume (energy), while the time required depends on flow rate (power).

This energy-power relationship explains why power appears in contexts involving time. Battery life depends on stored energy divided by power consumption—a one-watt load drains a ten-watt-hour battery in ten hours, while a ten-watt load drains the same battery in one hour. Electricity bills charge for energy consumed measured in kilowatt-hours, which equals power in kilowatts multiplied by time in hours. A one-kilowatt appliance running for ten hours consumes ten kilowatt-hours, costing the same as a ten-kilowatt appliance running for one hour.

The Watt: Quantifying Power

The watt, named after James Watt who significantly improved steam engine efficiency, quantifies power as one joule per second—the rate of energy transfer equal to one joule of energy transferred every second. This definition directly links power to energy and time, making watts fundamentally a rate unit like miles per hour or meters per second, but describing energy flow rather than physical motion.

Common power levels provide intuitive reference points for understanding watts. A typical LED flashlight might consume one watt, a smartphone while charging draws five to twenty watts, a laptop consumes thirty to sixty watts during normal use, a desktop computer with monitor might use one hundred to three hundred watts, a hair dryer pulls one thousand to eighteen hundred watts, and an electric stove burner consumes one thousand to three thousand watts per burner. These familiar examples help calibrate intuition about what various power levels mean practically.

Larger power levels use metric prefixes for convenience. Kilowatts equal one thousand watts, megawatts equal one million watts, and gigawatts equal one billion watts. Household electrical service typically provides several kilowatts maximum—perhaps five kilowatts for a small apartment through twenty or more kilowatts for a large house with central air conditioning and electric heating. Power plants generate megawatts to gigawatts, distributing power across transmission grids to millions of consumers.

Power as the Product of Voltage and Current

The fundamental power equation for DC circuits—power equals voltage times current, written P equals V times I—reveals that power depends on both the electrical pressure (voltage) and flow rate (current). Doubling voltage while maintaining current doubles power, doubling current while maintaining voltage also doubles power, and doubling both voltage and current quadruples power. This multiplicative relationship means that high power can result from high voltage with moderate current, moderate voltage with high current, or high values of both.

Understanding why power equals voltage times current requires connecting to the fundamental definitions. Voltage measures energy per unit charge—how much energy each coulomb of charge carries. Current measures charge flow rate—how many coulombs pass per second. Multiplying these gives energy per coulomb times coulombs per second, which simplifies to energy per second—exactly the definition of power. This dimensional analysis confirms that voltage times current necessarily yields power.

The equation explains everyday observations. A twelve-volt car battery delivering one hundred amperes during engine starting transfers twelve hundred watts—over one horsepower—for the brief starting interval despite the relatively low twelve-volt voltage because the high current compensates. A one hundred twenty volt household circuit delivering ten amperes provides twelve hundred watts to appliances, achieving the same power through higher voltage and lower current. A USB charger providing five volts at one ampere delivers five watts, adequate for slowly charging phones but insufficient for rapid charging which requires higher power through increased current, voltage, or both.

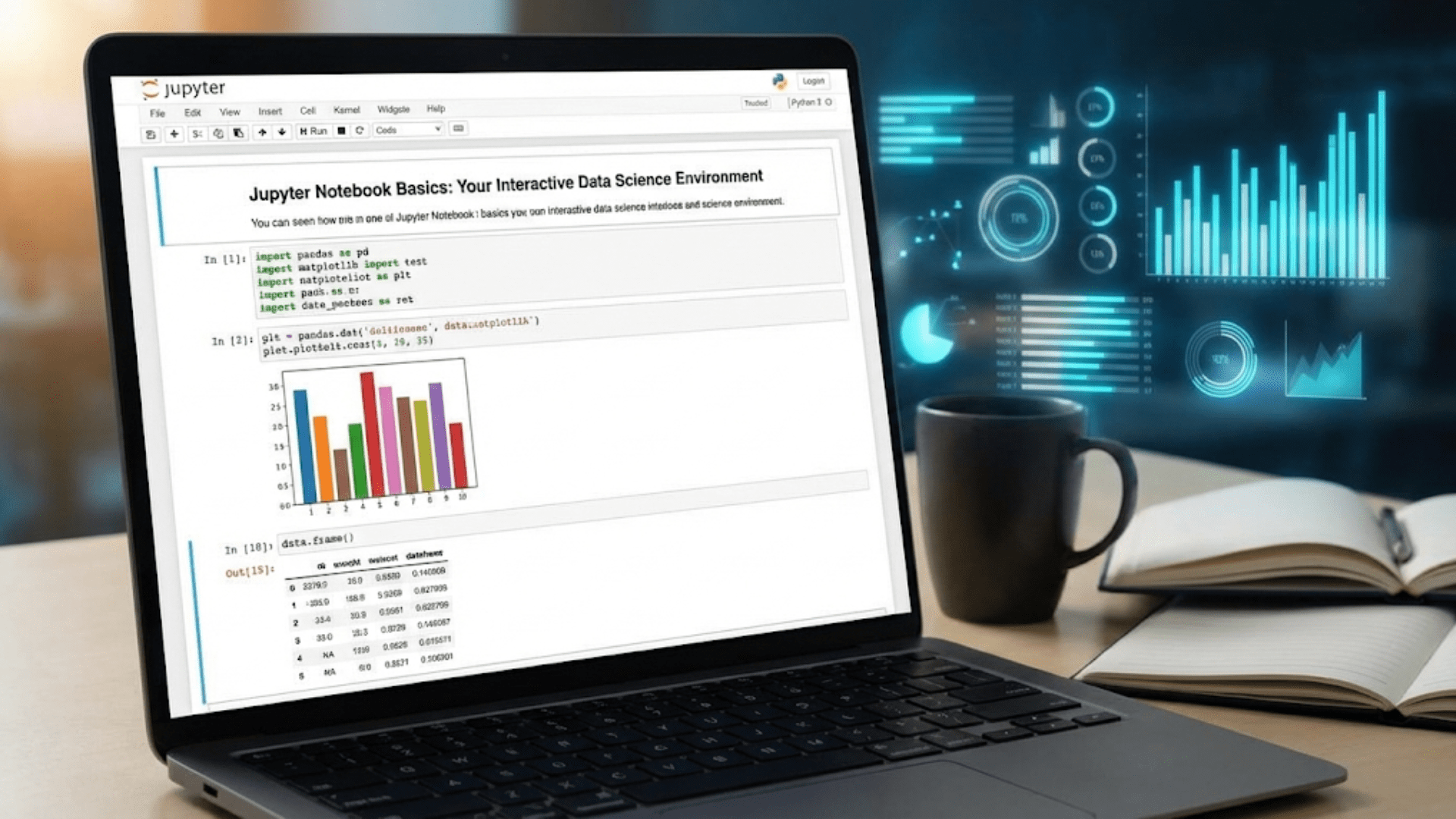

Calculating Power in DC Circuits

Applying the power equation to various circuit configurations enables predicting power consumption, sizing components appropriately, and understanding how power distributes across circuit elements.

Power Dissipation in Resistors

Resistors convert electrical energy into heat through the resistance that opposes current flow, with the power dissipation in a resistor calculated directly from the basic power equation combined with Ohm’s Law. When current I flows through resistance R, Ohm’s Law states that voltage across the resistor equals current times resistance, written V equals I times R. Substituting this into the power equation P equals V times I gives P equals I times R times I, which simplifies to P equals I squared times R. This form expresses power directly in terms of current and resistance without requiring voltage.

Alternatively, solving Ohm’s Law for current as I equals V divided by R and substituting into P equals V times I yields P equals V times V divided by R, or P equals V squared divided by R. This form calculates power from voltage and resistance without requiring current. These three equivalent power equations—P equals V times I, P equals I squared times R, and P equals V squared divided by R—provide flexibility for calculating power from whatever quantities are known.

For example, a one-kilohm resistor with ten volts across it dissipates power equal to ten volts squared divided by one thousand ohms equals one hundred divided by one thousand equals zero point one watts or one hundred milliwatts. The current through this resistor equals ten volts divided by one kilohm equals ten milliamps, confirming the power calculation as ten volts times ten milliamps equals one hundred milliwatts. If instead we know only that five milliamps flows through a one-kilohm resistor, power equals five milliamps squared times one kilohm equals twenty-five times ten to the negative six squared times one thousand equals twenty-five milliwatts.

Power Distribution in Series and Parallel Circuits

In series circuits, each resistor dissipates power according to the current through it and its resistance. Since the same current flows through all series resistors, those with larger resistance dissipate more power according to P equals I squared times R. If one ampere flows through two series resistors of one ohm and four ohms, the one-ohm resistor dissipates one squared times one equals one watt, while the four-ohm resistor dissipates one squared times four equals four watts. The total power dissipated equals the sum of individual powers—five watts in this example.

In parallel circuits, each resistor experiences the same voltage but carries current inversely proportional to its resistance. Lower resistance branches carry more current and thus dissipate more power according to P equals V squared divided by R. With ten volts across parallel resistors of ten ohms and forty ohms, the ten-ohm resistor dissipates ten squared divided by ten equals ten watts, while the forty-ohm resistor dissipates ten squared divided by forty equals two point five watts, for total dissipation of twelve point five watts.

The total power supplied by voltage sources equals the sum of all power dissipations in the circuit, following conservation of energy—electrical energy supplied must equal energy dissipated as heat or converted to other forms. A battery delivering ten watts to a circuit cannot indefinitely maintain that output because stored chemical energy depletes at ten joules per second. Calculating total circuit power enables estimating battery life by dividing stored energy in watt-hours by power consumption in watts.

Power Ratings on Components

Resistors and other components have maximum power ratings indicating safe continuous dissipation levels without overheating to failure. Common resistor power ratings include one-eighth watt, one-quarter watt, one-half watt, one watt, two watts, and higher for power resistors. Exceeding these ratings causes resistors to overheat, potentially changing resistance values, creating fire hazards, or failing catastrophically. Conservative design keeps dissipation well below ratings—typically fifty percent or less—ensuring reliability even when ambient temperatures rise or component tolerances cause higher-than-expected dissipation.

Physical resistor size correlates roughly with power rating because larger surface areas dissipate heat more effectively. One-eighth watt resistors are tiny surface-mount components or small through-hole resistors, one-quarter watt resistors are standard through-hole sizes familiar to hobbyists, one-half and one-watt resistors are noticeably larger, and multi-watt power resistors can be substantial components requiring heat sinking for rated dissipation. This size-power relationship provides rough visual verification that resistor power ratings match dissipation requirements.

When designing circuits, calculating expected dissipation for each resistor and selecting power ratings appropriately ensures reliable operation. A one-kilohm resistor with ten volts across it dissipates one hundred milliwatts, safely within a one-quarter watt (two hundred fifty milliwatt) rating but exceeding a one-eighth watt (one hundred twenty-five milliwatt) rating. The safe choice uses a component rated for at least twice the calculated dissipation, in this case one-quarter watt or larger. For production designs or critical applications, even larger derating factors ensure reliability despite worst-case combinations of tolerances and environmental conditions.

Practical Power Calculations

Applying power concepts to real circuits and devices reveals how power calculations inform design decisions and troubleshoot problems.

LED Power Consumption and Current-Limiting Resistor Dissipation

A typical LED might drop two volts forward when conducting twenty milliamps, dissipating power equal to two volts times twenty milliamps equals forty milliwatts. The LED converts most of this power to light and some to heat, functioning reliably at this power level. The current-limiting resistor in series with the LED dissipates additional power that must be considered in component selection.

For an LED circuit with a nine-volt battery, the series resistor must drop seven volts (nine-volt supply minus two-volt LED drop) at twenty milliamps, requiring three hundred fifty ohms by Ohm’s Law. The resistor dissipates seven volts times twenty milliamps equals one hundred forty milliwatts, well within a one-quarter watt resistor rating but exceeding one-eighth watt. The total circuit power equals nine volts times twenty milliamps equals one hundred eighty milliwatts, with forty milliwatts usefully converted to light in the LED and one hundred forty milliwatts wasted as heat in the resistor.

This example illustrates that in simple circuits, most power often dissipates unproductively rather than performing useful work. The resistor wastes nearly eighty percent of total power maintaining the correct current despite producing no light. More efficient approaches like switching regulators or constant-current LED drivers reduce this waste, but for simple circuits where efficiency is less critical than simplicity, resistive current limiting remains acceptable despite its inefficiency.

Motor Power and Mechanical Work

Electric motors convert electrical power into mechanical power with efficiency typically ranging from fifty to ninety-five percent depending on motor type, size, and operating conditions. A motor consuming one hundred watts electrical power with eighty percent efficiency delivers eighty watts mechanical power while dissipating twenty watts as heat in winding resistances and friction losses. The mechanical power equals torque times angular velocity, enabling calculation of torque from power and speed or vice versa.

For example, a motor delivering one-tenth horsepower mechanical output—approximately seventy-five watts since one horsepower equals seven hundred forty-six watts—at eighty percent efficiency consumes seventy-five divided by zero point eight equals ninety-four watts electrical power. At twelve volts, this motor draws ninety-four watts divided by twelve volts equals approximately seven point eight amperes. Power supply for this motor must deliver at least eight amperes continuously, with additional margin for starting surges that might briefly exceed continuous current by factors of five or more.

Understanding motor power requirements prevents undersized power supplies that collapse under motor loads, oversized supplies that waste money and space, and inadequate wiring that overheats from excessive current. The power calculation connecting voltage, current, and load requirements guides appropriate component selection throughout motor control systems.

Battery Life Calculations

Battery capacity specified in milliamp-hours (mAh) or amp-hours (Ah) indicates stored charge, while watt-hours (Wh) or kilowatt-hours (kWh) indicate stored energy. For a battery with nominal voltage V and capacity Q in amp-hours, stored energy equals V times Q watt-hours. A twelve-volt battery rated for ten amp-hours stores one hundred twenty watt-hours of energy.

Battery life for a constant load equals stored energy divided by power consumption. A device consuming six watts running from the one hundred twenty watt-hour battery lasts approximately twenty hours (one hundred twenty divided by six equals twenty). More precisely, battery voltage varies during discharge, so actual capacity delivered depends on discharge current and end-of-life voltage cutoff. Nonetheless, the energy-divided-by-power approximation provides useful estimates for planning applications and selecting battery capacity.

Multiple batteries can be combined in series for higher voltage or parallel for higher capacity. Two twelve-volt ten-amp-hour batteries in series provide twenty-four volts at ten amp-hours, storing two hundred forty watt-hours. The same batteries in parallel provide twelve volts at twenty amp-hours, also storing two hundred forty watt-hours—identical energy but different voltage-current characteristics suiting different applications. Understanding these relationships enables configuring batteries appropriately for voltage and energy requirements.

Power Supply Considerations

Power supplies must deliver sufficient power for connected loads while maintaining regulated voltage despite varying load currents, requiring understanding of power supply ratings and loading effects.

Power Supply Ratings and Capacity

Power supplies are rated for maximum continuous output power, typically specified as voltage times maximum current—for example, five volts at two amperes equals ten watts. Operating loads drawing less than rated power allows the supply to regulate voltage properly while dissipating heat within safe limits. Loads exceeding rated power cause voltage to drop, supplies to overheat, or protection circuits to shut down operation until faults clear.

Linear power supplies dissipate power equal to voltage dropped across series pass transistors times load current. A linear supply providing five volts at one ampere from a twelve-volt input dissipates seven volts (twelve minus five) times one ampere equals seven watts in the regulator, heating it substantially despite delivering only five watts to the load. This poor efficiency—five watts out for twelve watts in—limits linear supplies to lower power applications where simplicity outweighs efficiency.

Switching power supplies achieve much higher efficiency—typically eighty to ninety-five percent—by switching currents rapidly rather than dissipating power linearly. The same five volt, one ampere output might require only six watts input from a switching supply operating at eighty-three percent efficiency, dissipating only one watt as heat. This dramatic efficiency improvement enables switching supplies to deliver more power in smaller packages without excessive heating, explaining their dominance in modern electronics.

Loading Effects and Voltage Regulation

Power supplies have maximum current ratings beyond which voltage regulation fails or protection circuits activate. Loading supplies beyond ratings causes output voltage to sag below specified levels, potentially causing circuits to malfunction even if the supply doesn’t completely fail. Understanding how loads sum across multiple circuits ensures total current demand doesn’t exceed supply capacity.

For example, a five-volt three-ampere supply can deliver fifteen watts maximum. Connecting a circuit drawing one ampere (five watts), another drawing one point five amperes (seven point five watts), and a third drawing zero point three amperes (one point five watts) totals two point eight amperes or fourteen watts, safely within the fifteen-watt rating. Adding another device drawing one ampere would total three point eight amperes or nineteen watts, exceeding capacity and likely causing voltage sag or shutdown.

Planning power budgets during design ensures adequate supply capacity with margin for worst-case loading. Professional practice often sizes supplies for sixty to eighty percent of rated capacity under maximum expected load, leaving margin for component tolerances, supply aging, and unexpected additions without redesigning power systems.

Efficiency: Why Not All Power Does Useful Work

Understanding efficiency reveals how much consumed power actually performs intended functions versus being wasted as heat or other losses, guiding design choices that minimize waste.

Defining and Calculating Efficiency

Efficiency equals useful output power divided by total input power, typically expressed as a percentage. A motor converting eighty watts of one hundred watts input into mechanical work has eighty percent efficiency, with twenty watts lost to heat. The lost power represents energy that must be supplied but provides no benefit beyond heating, motivating efficiency improvements that reduce operating costs and heat dissipation requirements.

Mathematically, efficiency η (the Greek letter eta) equals P-out divided by P-in, or equivalently P-out divided by P-out plus P-loss where P-loss represents dissipated power. Rearranging gives P-loss equals P-in times one minus η, showing that losses equal input power times the inefficiency (one minus efficiency). For a one-hundred-watt input at eighty percent efficiency, losses equal one hundred times zero point two equals twenty watts.

High efficiency is desirable because it reduces energy costs, minimizes heat dissipation that might require expensive cooling systems, extends battery life in portable applications, and reduces environmental impact through lower energy consumption. However, higher efficiency often requires more complex or expensive designs, creating trade-offs between efficiency and cost, size, or complexity that designers must balance based on application requirements.

Examples of Efficiency in Common Devices

Incandescent light bulbs are notoriously inefficient, converting perhaps five percent of input power to visible light while dissipating ninety-five percent as heat. A sixty-watt incandescent bulb produces about three watts of light, wasting fifty-seven watts as heat—effective as a small heater but inefficient for illumination. LED bulbs achieve fifteen to twenty percent efficiency or higher, producing equivalent light from nine watts while wasting far less energy as heat and thus reducing electricity costs dramatically over the bulb’s life.

Smartphone chargers exemplify efficiency variation across designs. Older linear chargers might be fifty to sixty percent efficient, wasting nearly half the input power as heat in the charger itself. Modern switching chargers achieve eighty to ninety percent efficiency, delivering most input power to the phone battery while minimizing charger heating. The efficiency difference is tangible—a five-watt output from a sixty-percent efficient charger requires eight point three watts input and wastes three point three watts, while ninety percent efficiency requires only five point six watts input and wastes zero point six watts, reducing waste by eighty percent.

Conclusion: Power as the Practical Measure

Understanding electrical power transforms abstract voltage and current into concrete knowledge about energy consumption, battery life, heat generation, and circuit capabilities that directly impact electronics design and daily energy use. The watt quantifies power as the rate of energy transfer, with the fundamental equation P equals V times I connecting power to voltage and current in ways that enable calculating power requirements, sizing components, estimating costs, and understanding the relationship between electricity and the work it performs.

Power calculations using P equals V times I and its variants P equals I squared times R and P equals V squared divided by R provide tools for analyzing circuits, determining component dissipation, sizing power supplies, and estimating battery life. These calculations distinguish designs that function reliably from those that fail through overheated components, inadequate power delivery, or premature battery depletion. The ability to calculate and reason about power represents essential practical knowledge for anyone working with electronics.

Power ratings on components indicate safe dissipation limits that must be respected to prevent failures, with conservative design maintaining dissipation well below ratings ensuring reliability. Understanding these ratings and calculating actual dissipation enables selecting appropriately rated components that survive worst-case conditions without excessive cost from overspecification.

Efficiency connects input and output power, revealing how much energy performs useful work versus being wasted as heat. High efficiency reduces operating costs, extends battery life, minimizes cooling requirements, and lessens environmental impact, motivating design choices that improve efficiency when benefits justify costs and complexity. Understanding efficiency enables evaluating trade-offs between performance, cost, and energy consumption across diverse applications from light bulbs through chargers to industrial equipment.

The practical implications of power understanding extend from electronics design through home energy management to evaluating appliance specifications and estimating electricity costs. Knowing that a fifteen-hundred-watt space heater running eight hours daily consumes twelve kilowatt-hours per day enables calculating monthly costs by multiplying by your electricity rate. Understanding that LED bulbs deliver equivalent light to incandescent bulbs while consuming one-sixth the power enables calculating long-term savings justifying higher upfront costs. These practical applications make power one of the most immediately useful electrical concepts for both hobbyists and professionals.