Introduction

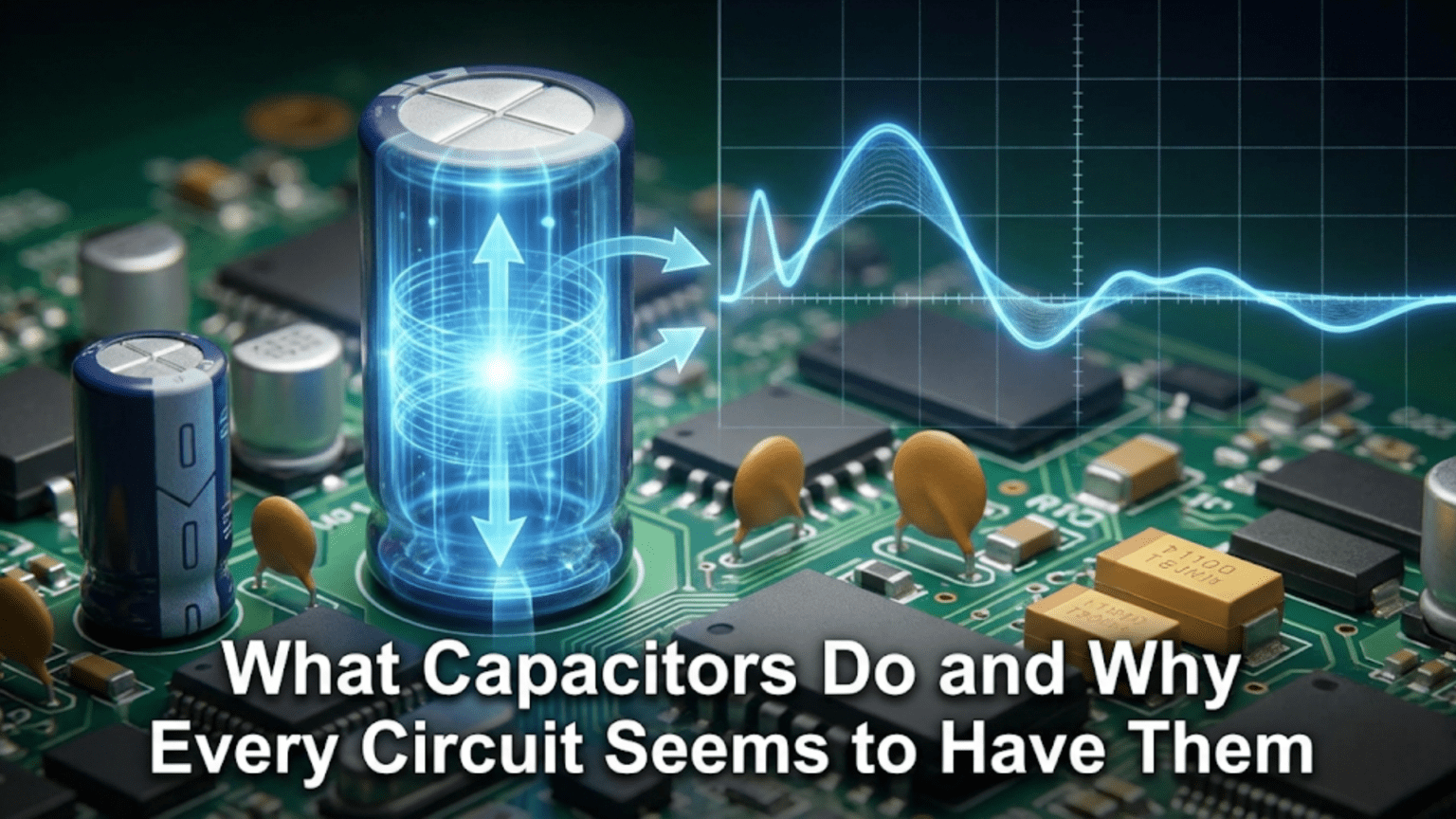

Open any electronic device—a computer, a smartphone, a power supply, an audio amplifier—and you will find capacitors scattered throughout the circuit board. These components, appearing in various forms from tiny surface-mount chips to large cylindrical cans, seem to be everywhere in modern electronics. A typical motherboard might contain hundreds of capacitors. A simple power supply uses several dozen. Even the simplest battery-powered circuits usually include at least a few capacitors. For beginners learning electronics, this ubiquity raises an obvious question: what exactly do all these capacitors do, and why does every circuit seem to need them?

Capacitors perform a remarkable array of functions that are absolutely essential to modern electronics. At their core, capacitors store electrical energy in electric fields, then release that energy when needed. This simple capability enables capacitors to smooth voltage ripples, filter signals, couple AC while blocking DC, provide temporary power during brief interruptions, set timing intervals, tune resonant circuits, protect against voltage spikes, and perform countless other essential functions. Unlike resistors which dissipate energy as heat, capacitors store and release energy without inherent losses, making them fundamentally different in character and application.

Understanding what capacitors do and why circuits need them provides critical knowledge for anyone working with electronics. When you can explain why a particular circuit includes specific capacitors in specific locations, you demonstrate genuine circuit comprehension. When you can select appropriate capacitor types and values for new designs, you have progressed from following instructions to creating functional circuits independently. This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of capacitor functions from fundamental principles, developing intuition for recognizing capacitor roles in real circuits and selecting appropriate values and types for your own designs.

The Fundamental Characteristic: Energy Storage in Electric Fields

Every capacitor function ultimately derives from the capacitor’s ability to store electrical energy in an electric field created between two conductive plates separated by an insulating material called a dielectric. Understanding this fundamental characteristic provides the foundation for understanding all capacitor applications.

The Physical Structure and Electrical Behavior

A capacitor consists of two conductors (plates) separated by an insulator (dielectric). When voltage is applied across the capacitor, electric charge accumulates on one plate while an equal and opposite charge depletes from the other plate. This charge separation creates an electric field in the dielectric material between the plates. The electric field stores energy—energy that can be recovered by allowing the capacitor to discharge.

The amount of charge a capacitor can store for a given voltage defines its capacitance, measured in farads. One farad represents the capacitance that stores one coulomb of charge when one volt is applied. This is an enormous capacitance; most practical capacitors range from picofarads (trillionths of a farad) to millifarads (thousandths of a farad), with supercapacitors reaching into the farad range.

The relationship between charge, capacitance, and voltage is expressed as Q = C × V, where Q is charge in coulombs, C is capacitance in farads, and V is voltage in volts. This simple equation underlies all capacitor behavior. It reveals that capacitance determines how much charge accumulates for a given voltage, and inversely, how much voltage results from a given charge.

Voltage Cannot Change Instantaneously

A critical insight follows from the charge-voltage relationship: since current is the rate of charge flow (I = dQ/dt), and charge on a capacitor relates directly to voltage (Q = C × V), capacitor voltage cannot change instantaneously unless infinite current flows. Mathematically, I = C × (dV/dt), meaning current equals capacitance times the rate of voltage change. To change voltage instantly (infinite dV/dt) would require infinite current.

This resistance to instantaneous voltage change makes capacitors fundamentally different from resistors, which respond instantly to voltage changes. A capacitor “remembers” its voltage through stored charge, and that voltage can only change as charge flows on or off the capacitor plates. This characteristic underlies many capacitor applications including filtering, energy storage, and timing.

Energy Storage Quantified

The energy stored in a capacitor equals one-half capacitance times voltage squared: E = ½ CV². This equation reveals several important insights. First, stored energy increases with the square of voltage, so doubling voltage quadruples stored energy. Second, larger capacitance stores more energy at the same voltage. Third, significant energy storage requires either high voltage, high capacitance, or both.

A 1000 microfarad capacitor charged to 100 volts stores E = ½ × 0.001F × (100V)² = 5 joules of energy. While five joules might not sound like much, it is sufficient to deliver a dangerous or potentially lethal shock. Large capacitors in power supplies can store hundreds or thousands of joules, remaining dangerous long after equipment is powered off. This energy storage capability makes capacitors useful but demands respect and caution when working with charged capacitors.

Power Supply Filtering: Smoothing the Ripples

Perhaps the most common capacitor application is power supply filtering, where capacitors smooth the pulsating DC output from rectifiers into steady DC suitable for powering electronic circuits.

The Rectification Problem

AC-to-DC conversion using diode rectifiers produces pulsating DC, not smooth DC. A full-wave rectifier connected to 60 Hz AC produces DC that pulses at 120 Hz, rising to peak voltage then falling toward zero twice per AC cycle. While this pulsating voltage has the correct polarity for DC circuits, its large variations make it unsuitable for most applications. Electronic circuits require stable supply voltages with minimal ripple.

Without filtering, a rectified 12-volt supply might vary from nearly zero volts to 17 volts (the peak of the AC waveform) 120 times per second. This voltage variation would cause lights to flicker, audio amplifiers to produce hum, and digital circuits to malfunction. Clearly, we need a way to smooth these voltage pulsations into steady DC.

How Filter Capacitors Work

A large capacitor placed across the rectifier output stores charge when rectifier voltage is high and releases charge when rectifier voltage falls. During the brief peaks when rectifier output voltage exceeds capacitor voltage, current flows into the capacitor, charging it toward peak voltage. During the longer intervals when rectifier output voltage falls below capacitor voltage, the capacitor discharges into the load, maintaining voltage despite the rectifier providing no current.

The capacitor acts as a reservoir, filling during abundant supply and providing during scarcity. This reservoir action dramatically reduces voltage ripple. Instead of voltage falling to near zero between rectifier pulses, it falls only slightly as the capacitor partially discharges before the next rectifier pulse arrives to recharge it.

Selecting Filter Capacitor Values

The appropriate filter capacitor value depends on load current and acceptable ripple voltage. Higher load current drains the capacitor faster, requiring larger capacitance to maintain acceptable ripple. Lower acceptable ripple requires larger capacitance to limit voltage droop between rectifier pulses.

A rough guideline for 60 Hz full-wave rectified supplies suggests approximately 1000-2000 microfarads per ampere of load current for ripple below one volt. A supply delivering 2 amps might use a 4000 microfarad filter capacitor. More precise calculations consider ripple frequency, desired ripple voltage, and load resistance, but this guideline provides reasonable starting values.

Filter capacitors in power supplies are typically aluminum electrolytic capacitors, which provide high capacitance in relatively small packages at reasonable cost. These capacitors must have voltage ratings well above the peak rectified voltage to ensure reliability. A 12-volt DC supply might use capacitors rated for 25 or 35 volts to provide adequate safety margin.

Multiple Filter Capacitor Stages

Demanding applications use multiple filtering stages to achieve very low ripple. An initial large-value capacitor provides bulk filtering, followed by a series resistor or inductor and then another capacitor forming an LC or RC filter. The series element limits current during load transients and provides impedance that, combined with the second capacitor, creates additional ripple attenuation.

Some designs use active filtering with voltage regulators that provide both voltage stabilization and ripple reduction. The combination of passive LC filtering followed by active regulation achieves ripple levels orders of magnitude lower than simple capacitive filtering alone.

Decoupling and Bypassing: Local Energy Reservoirs

Modern digital and analog circuits require stable power supply voltages despite rapidly changing current demands. Decoupling capacitors provide local energy storage that supplies brief current surges without causing voltage drops, while bypassing capacitors shunt high-frequency noise to ground before it can affect circuit operation.

The Supply Impedance Problem

Power supply conductors have impedance—primarily inductance in PCB traces and wire leads. When circuit current changes rapidly, this impedance causes voltage drops according to V = L × (dI/dt). A microprocessor switching millions of transistors simultaneously can change current by hundreds of milliamps in nanoseconds. Even small inductance causes significant voltage drops during such rapid current changes.

If integrated circuits drew all their current directly from the power supply through these inductive connections, supply voltage at the IC would fluctuate wildly during switching events. These voltage fluctuations would cause timing errors, logic failures, and noise injection into sensitive analog circuits. Clearly, we need local energy storage to buffer rapid current demands.

Decoupling Capacitor Function

Decoupling capacitors placed physically close to integrated circuit power pins provide local charge reservoirs that supply current during rapid transients. When the IC suddenly demands increased current, the nearby decoupling capacitor immediately supplies that current through very short, low-inductance connections. This local supply maintains stable voltage at the IC even though current through the higher-inductance power supply connections changes more slowly.

The decoupling capacitor recharges from the power supply during intervals when IC current demand decreases. The power supply sees gradual average current changes rather than sharp transients, while the IC sees stable voltage despite its own rapid current variations. This arrangement provides the best of both worlds: the power supply can use relatively high-impedance distribution networks, while the IC receives essentially zero-impedance supply.

Selecting Decoupling Capacitor Values

Effective decoupling requires capacitors with low equivalent series inductance (ESL) and low equivalent series resistance (ESR). Ceramic capacitors excel at high-frequency decoupling due to their very low ESL. Values from 0.1 to 10 microfarads typically provide adequate decoupling for digital ICs, with the specific value depending on IC current consumption and switching speed.

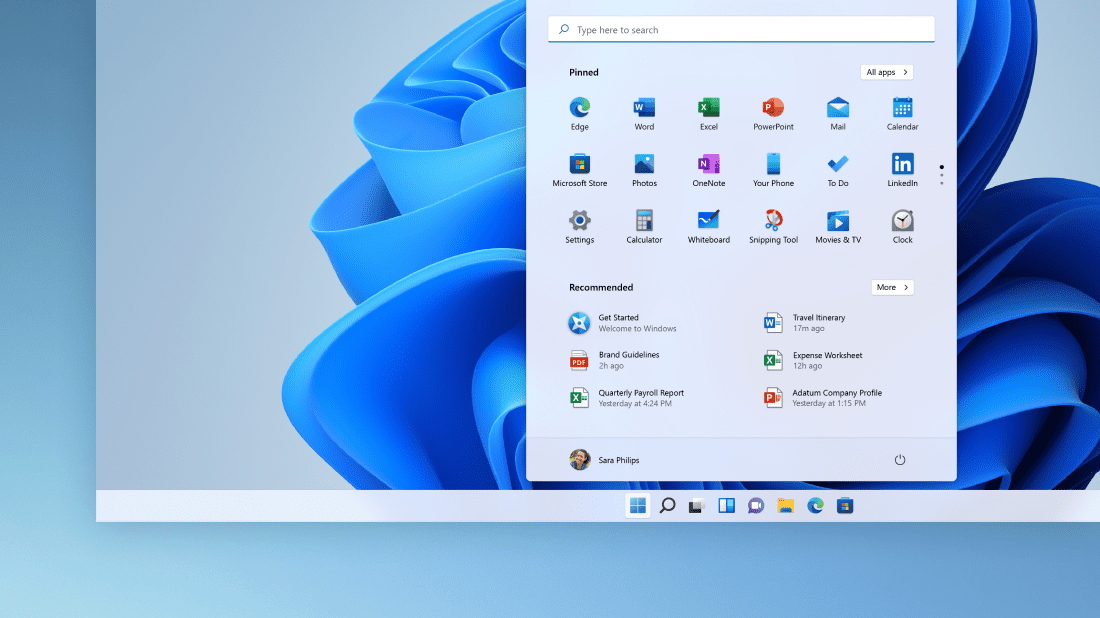

Modern practice often uses multiple decoupling capacitors of different values in parallel at each power supply location. A typical arrangement might include a 10 microfarad bulk capacitor, a 1 microfarad intermediate capacitor, and a 0.1 microfarad high-frequency capacitor. This combination provides low impedance over a broad frequency range, with different capacitor values optimized for different frequency bands.

Physical placement critically affects decoupling performance. Decoupling capacitors should be placed as close as possible to IC power pins with short, wide traces minimizing inductance. Long traces or vias to decoupling capacitors defeat their purpose by introducing the very inductance they are meant to overcome.

Bypass Capacitors for Noise Reduction

Bypass capacitors shunt high-frequency noise to ground, preventing it from coupling into sensitive circuits. These capacitors connect between signal or power lines and ground, providing low-impedance paths for high-frequency currents while presenting high impedance to desired low-frequency signals.

The capacitor’s impedance decreases with increasing frequency according to Z = 1/(2πfC), making it an excellent high-frequency short circuit while remaining nearly open at low frequencies. A 0.1 microfarad capacitor has approximately 1600 ohms impedance at 1 kHz but only 16 ohms at 100 kHz and 1.6 ohms at 1 MHz. This frequency-dependent impedance makes it ideal for bypassing high-frequency noise while not loading low-frequency signals.

Bypass capacitors appear at circuit inputs to block noise from entering, at power supply connections to shunt switching noise to ground, and throughout mixed-signal circuits to isolate digital noise from sensitive analog sections. Their liberal use throughout modern circuits reflects the critical importance of noise control in reliable circuit operation.

AC Coupling and DC Blocking

Capacitors pass AC signals while blocking DC, a characteristic exploited in countless circuits for coupling signals between stages while isolating DC bias levels.

The DC Blocking Characteristic

Since current through a capacitor equals capacitance times the rate of voltage change (I = C × dV/dt), constant DC voltage (dV/dt = 0) produces zero current. The capacitor blocks DC completely—no steady-state DC current flows through a capacitor regardless of DC voltage across it (within voltage rating limits). This makes capacitors perfect for isolating DC levels while allowing AC signals to pass.

Consider an amplifier stage biased to operate at 6 volts DC. We want to couple AC signals into this stage from a previous stage operating at different DC bias voltage without disturbing either stage’s bias. A series coupling capacitor accomplishes this perfectly. The capacitor passes AC signals while blocking DC, allowing each stage to maintain independent bias voltages.

Choosing Coupling Capacitor Values

The coupling capacitor forms a high-pass filter with the input impedance of the following stage. At low frequencies where capacitive reactance becomes large, signal attenuation increases. The -3dB point (where signal amplitude falls to 70.7% of its high-frequency value) occurs at f = 1/(2πRC), where R is the input impedance and C is coupling capacitance.

For audio applications requiring response down to 20 Hz and coupling into a 10kΩ input impedance, the required capacitance is C = 1/(2π × 20Hz × 10kΩ) = 0.8 microfarads. A standard 1 microfarad capacitor provides adequate coupling with some margin. Higher capacitance extends low-frequency response; lower capacitance reduces it.

AC Coupling Applications

AC coupling appears throughout electronics wherever signals must pass between circuits with different DC levels. Audio equipment uses coupling capacitors between amplifier stages and at inputs and outputs. Radio receivers use coupling between RF stages. Oscilloscope AC coupling mode inserts a capacitor to remove DC offsets from displayed signals. Sensor interfaces couple AC sensor signals while blocking DC sensor bias voltages.

The capacitor’s voltage rating must exceed the maximum voltage difference that might appear across it. In audio circuits with ±15V supplies, coupling capacitors might see up to 30 volts DC if one stage sits at positive supply and the other at negative supply. Using capacitors rated for at least twice the maximum expected voltage provides adequate safety margin.

Timing Applications: RC Time Constants

Capacitors combined with resistors create RC networks with time constants that determine charging and discharging rates, enabling precise timing functions throughout electronics.

The Exponential Response

When a capacitor charges through a resistor from a fixed voltage source, capacitor voltage follows an exponential curve approaching the source voltage asymptotically. The time constant τ (tau) equals the product of resistance and capacitance: τ = RC. After one time constant, the capacitor reaches approximately 63.2% of its final voltage. After five time constants, it reaches about 99.3% of final voltage, effectively fully charged for practical purposes.

Discharge follows a similar exponential decay. When a charged capacitor discharges through a resistor, voltage falls exponentially toward zero, dropping to about 36.8% of initial voltage after one time constant and to less than 1% after five time constants.

These predictable exponential responses enable precise timing. By selecting appropriate resistor and capacitor values, designers create time constants from microseconds to hours, enabling everything from high-speed pulse generation to long-duration timing delays.

Timer Circuits

The ubiquitous 555 timer IC uses RC networks to set timing intervals. In monostable mode, triggering the 555 initiates a timing cycle during which output goes high while a capacitor charges through a resistor. When capacitor voltage reaches a threshold (typically 2/3 of supply voltage), timing ends and output goes low. The duration depends directly on RC time constant: T = 1.1RC for the 555.

In astable mode, the 555 continuously charges and discharges a capacitor through resistors, creating a square wave output with frequency determined by component values: f ≈ 1.44/((R1 + 2R2)C). This simple configuration generates clock signals, tone generators, LED flashers, and countless other timing applications.

Delay Circuits

Simple delay circuits charge capacitors through resistors until voltage reaches a threshold that triggers some action. A Schmitt trigger comparator monitors capacitor voltage, switching states when voltage crosses defined thresholds. The delay between initial trigger and output switching depends on RC time constant and threshold voltages.

More sophisticated delays might use voltage-controlled current sources charging capacitors for improved linearity, or microcontrollers with internal or external RC networks for digitally controllable delays. Regardless of implementation, the RC time constant remains fundamental to timing circuit operation.

Filtering: Frequency-Selective Signal Processing

Capacitors form the heart of countless filter circuits that selectively pass or reject signals based on frequency. These filters shape frequency response in audio systems, remove interference in communication receivers, extract specific signals from complex waveforms, and perform countless other frequency-selective operations.

Low-Pass Filters

A resistor in series with a capacitor to ground creates a simple low-pass filter passing low frequencies while attenuating high frequencies. At low frequencies, capacitive reactance is high and the capacitor presents minimal loading. At high frequencies, capacitive reactance decreases and the capacitor increasingly shunts signal to ground.

The cutoff frequency occurs where capacitive reactance equals resistance: f_c = 1/(2πRC). Below cutoff, signals pass with minimal attenuation. Above cutoff, attenuation increases at 6 dB per octave (20 dB per decade). This first-order rolloff provides gentle frequency discrimination suitable for many applications.

Multiple RC sections cascade for steeper rolloff. A two-section (second-order) filter rolls off at 12 dB per octave; a third-order at 18 dB per octave. The increased rolloff rate provides sharper frequency discrimination but requires more components and careful design to avoid peaking at the cutoff frequency.

High-Pass Filters

Reversing component positions creates a high-pass filter: capacitor in series with the signal path, resistor to ground. At low frequencies, capacitive reactance is high and signals are blocked. At high frequencies, capacitive reactance decreases and signals pass freely. The cutoff frequency again occurs at f_c = 1/(2πRC).

High-pass filters remove DC offsets, block low-frequency noise, and implement AC coupling with controlled frequency response. Microphone preamplifiers use high-pass filters to remove subsonic frequencies that waste amplifier power without producing audible sound. Sensor signal conditioning uses high-pass filtering to extract AC variations while rejecting DC sensor offset.

Band-Pass and Band-Reject Filters

Combining high-pass and low-pass sections creates band-pass filters passing a specific frequency range while rejecting frequencies above and below. Setting the high-pass cutoff below the low-pass cutoff creates a passband between cutoff frequencies. Audio equalizers, communication receivers, and spectrum analyzers all use band-pass filters to select desired frequency bands.

Band-reject filters (also called notch filters) do the opposite, rejecting a specific frequency range while passing others. A capacitor and inductor in parallel create a resonant circuit with very low impedance at resonance. Placed in series with the signal path, this LC combination blocks the resonant frequency while passing others. Applications include removing power line interference (50/60 Hz notch filters) and eliminating specific spurious frequencies in communication systems.

Active Filters

Operational amplifiers combined with RC networks create active filters offering advantages over passive RC filters. Active filters can provide voltage gain simultaneously with filtering, avoiding the insertion loss of passive filters. They achieve complex frequency responses including Butterworth, Chebyshev, and Bessel characteristics that optimize different performance parameters. They implement high-order filters without inductors, which are larger, more expensive, and less ideal than capacitors.

The Sallen-Key topology, state-variable filters, and biquad filters represent common active filter configurations. Despite their variety, all rely fundamentally on capacitors to create frequency-dependent impedance that shapes filter response.

Power Factor Correction and Motor Starting

In AC power systems, capacitors correct power factor by offsetting inductive reactance, and provide starting torque for single-phase motors.

Understanding Power Factor

Inductive loads like motors, transformers, and ballasts cause current to lag voltage in AC circuits. This phase shift means instantaneous voltage and current do not peak simultaneously, reducing real power transfer compared to the apparent power (voltage × current product). Power factor, the ratio of real power to apparent power, quantifies this inefficiency.

Poor power factor requires higher current for a given real power delivery, increasing resistive losses in distribution wiring and requiring larger transformers and distribution equipment. Utilities often charge commercial and industrial customers penalties for poor power factor, providing economic incentive for correction.

Capacitive Power Factor Correction

Adding capacitors in parallel with inductive loads provides leading current that cancels lagging current from inductors, bringing net current closer to being in phase with voltage. The capacitor supplies reactive power that oscillates between source and load without being consumed, allowing the source to provide primarily real power.

Power factor correction capacitors must be sized appropriately for the inductive load. Too little capacitance provides incomplete correction; too much creates leading power factor with its own inefficiencies. Automatic power factor correction systems switch capacitor banks in and out based on load conditions, maintaining near-unity power factor across varying loads.

Motor Starting Capacitors

Single-phase AC motors require special techniques to create starting torque. A common approach uses a starting capacitor in series with an auxiliary winding. During starting, the capacitor creates a phase shift between main and auxiliary winding currents, creating the rotating magnetic field necessary for motor starting. Once the motor reaches running speed, a centrifugal switch disconnects the starting capacitor.

Some motors use run capacitors that remain connected during normal operation, improving efficiency and power factor. These capacitors must be designed for continuous AC operation, while starting capacitors only operate briefly during starting sequences and can use different construction optimized for high short-term currents.

Energy Storage for Power Backup

Capacitors store energy for brief power interruptions, providing hold-up time that allows orderly shutdown or bridges momentary power losses.

Hold-Up Time in Power Supplies

When AC input power fails, the energy stored in power supply filter capacitors continues supplying the load until capacitor voltage falls below the regulator’s minimum operating voltage. This hold-up time allows equipment to complete in-progress operations, save data, or signal an orderly shutdown before power is completely lost.

The available hold-up time depends on stored energy and load power. Energy stored in a capacitor is E = ½CV². As the capacitor discharges from voltage V1 to V2, the available energy is ½C(V1² – V2²). Dividing by load power gives hold-up time. A 1000 microfarad capacitor at 400 volts initially stores 80 joules. If voltage can fall to 300 volts before the regulator drops out, 35 joules are available. At 10 watts load power, this provides 3.5 seconds of hold-up time.

Supercapacitors for Extended Backup

Supercapacitors (also called ultracapacitors) achieve capacitances of farads to thousands of farads through specialized electrode structures. These enormous capacitances store substantial energy even at relatively low voltages. A 100-farad supercapacitor at 2.7 volts stores 364 joules, enough to maintain a low-power microcontroller system for minutes or even hours.

Supercapacitors find applications in backup power for real-time clocks, memory retention during battery changes, energy storage in regenerative braking systems, and buffer storage in energy harvesting applications. Their ability to charge and discharge rapidly, long cycle life, and environmentally benign materials make them attractive alternatives to batteries for certain applications.

Noise Suppression and EMI Control

Capacitors suppress electrical noise and control electromagnetic interference by providing low-impedance paths for high-frequency currents that would otherwise radiate or couple into sensitive circuits.

Supply Line Noise Filtering

Digital circuits create current spikes during switching transitions. These spikes inject noise into power supply lines that can affect other circuits sharing the same supply. Capacitors placed across supply lines provide low-impedance paths for high-frequency noise currents, shunting them to ground before they can propagate to other circuits.

The capacitor value and type should be chosen based on the noise frequencies present. Small ceramic capacitors (0.01 to 0.1 microfarads) effectively shunt very high frequency noise (tens to hundreds of megahertz). Larger capacitors (1 to 100 microfarads) address lower frequency noise components. Using multiple capacitor values in parallel provides broad-spectrum noise suppression.

Input/Output Filtering

Noise on signal lines entering or leaving equipment can cause malfunction or radiate electromagnetic interference violating regulatory limits. Capacitors from signal lines to ground filter this noise, with the capacitor value chosen to provide low impedance at noise frequencies while not loading signal frequencies excessively.

LC or RC filters on signal lines provide more aggressive noise filtering when necessary. These filters must be carefully designed not to distort signals or limit bandwidth excessively. Communication interfaces like RS-232, USB, and Ethernet often include input/output filtering to meet EMI requirements and improve noise immunity.

Snubber Circuits

Inductive loads like motors and relays create voltage spikes when switched off due to collapsing magnetic fields. These spikes can damage switching transistors or contacts and radiate interference. RC snubber circuits placed across the inductive load suppress these spikes. The resistor limits current through the capacitor, while the capacitor absorbs energy from the collapsing magnetic field, limiting voltage rise.

Snubber component values depend on inductance being suppressed and acceptable voltage overshoot. Typical snubber capacitors range from 0.01 to 1 microfarad, with resistors from tens to hundreds of ohms. The combination effectively clamps voltage transients while dissipating absorbed energy safely in the resistor.

Tuning and Resonance

Capacitors combined with inductors create LC resonant circuits that respond selectively to specific frequencies, enabling radio tuning, oscillators, and frequency-selective filters.

LC Resonance Fundamentals

An inductor and capacitor in parallel or series create resonance at the frequency where inductive and capacitive reactances are equal and opposite. At resonance, these reactances cancel, leaving only resistive impedance. Below resonance, the circuit appears capacitive; above resonance, inductive.

The resonant frequency is f = 1/(2π√(LC)). This simple equation enables precise frequency selection by choosing appropriate component values. A 1 microhenry inductor with a 1000 picofarad capacitor resonates at approximately 5 MHz. Changing capacitance to 100 pF increases resonant frequency to about 16 MHz.

Radio Tuning

AM radios use variable capacitors (tuning capacitors) to adjust LC resonant circuit frequency, selecting desired stations while rejecting others. Turning the tuning knob varies capacitance, shifting the resonant frequency across the AM band. The LC circuit has high impedance at resonance, maximum voltage develops across it, and this signal is detected and amplified.

Modern receivers often use electronic tuning with varactor diodes—diodes whose capacitance varies with applied reverse voltage. Varying control voltage changes varactor capacitance, tuning the LC circuit without mechanical components. This enables digital frequency control and eliminates wear from mechanical tuning mechanisms.

Oscillators

Many oscillators use LC resonant circuits to determine frequency. The Colpitts oscillator, Hartley oscillator, and Clapp oscillator all employ LC tanks in their feedback networks. The LC network provides frequency-selective positive feedback that sustains oscillation at the resonant frequency. Crystal oscillators use the same principle but employ a quartz crystal’s extremely stable mechanical resonance instead of LC electrical resonance.

Voltage-controlled oscillators (VCOs) use varactor diodes to enable electronic frequency control. Varying the control voltage changes VCO frequency, enabling frequency modulation, frequency synthesis in phase-locked loops, and voltage-to-frequency conversion.

Conclusion: The Universal Energy Storage Element

Capacitors appear in virtually every circuit because they perform so many essential functions—functions that cannot be accomplished with resistors, inductors, or active devices alone. They smooth power supply ripples, provide local energy storage for decoupling, couple AC while blocking DC, set timing through RC networks, filter signals based on frequency, correct power factor, provide backup energy, suppress noise, and enable resonant tuning. No other passive component type serves such diverse purposes across such varied applications.

Understanding capacitors deeply—not just knowing they “store charge” but comprehending how that storage enables their many applications—transforms circuits from mysterious assemblages of parts into comprehensible systems. When you see a capacitor in a circuit, you should be able to deduce its function from context. Is it a filter capacitor smoothing power supply ripple? A decoupling capacitor providing local energy storage? A coupling capacitor passing AC while blocking DC? A timing capacitor setting an RC time constant? Each capacitor exists for specific reasons, and understanding those reasons provides genuine circuit comprehension.

The next time you examine a circuit populated with numerous capacitors, appreciate that each serves a specific, necessary purpose. These energy storage elements filter power, couple signals, set timing, suppress noise, enable resonance, and perform countless other functions that make modern electronics possible. Without capacitors, the electronic world as we know it simply could not exist. Mastering their behavior and applications is essential for anyone serious about understanding and creating electronic circuits.

As you continue your electronics journey, develop intuition for appropriate capacitor values and types in different applications. Power supply filter capacitors typically range from hundreds to thousands of microfarads. Decoupling capacitors commonly fall between 0.1 and 10 microfarads. Coupling capacitors might be anywhere from 0.1 to 100 microfarads depending on frequency response requirements. Timing capacitors range from picofarads to hundreds of microfarads depending on time constants needed. This developing sense of typical values and appropriate types helps you design circuits correctly and recognize errors in existing designs.

Capacitors are not optional accessories that enhance circuits—they are fundamental components without which most circuits simply cannot function. Their ability to store and release energy, pass AC while blocking DC, and provide frequency-dependent impedance makes them indispensable. Every circuit designer must understand capacitors thoroughly to create reliable, functional circuits. This understanding positions you to move beyond following instructions to truly comprehending and creating the electronic systems that increasingly shape our world.