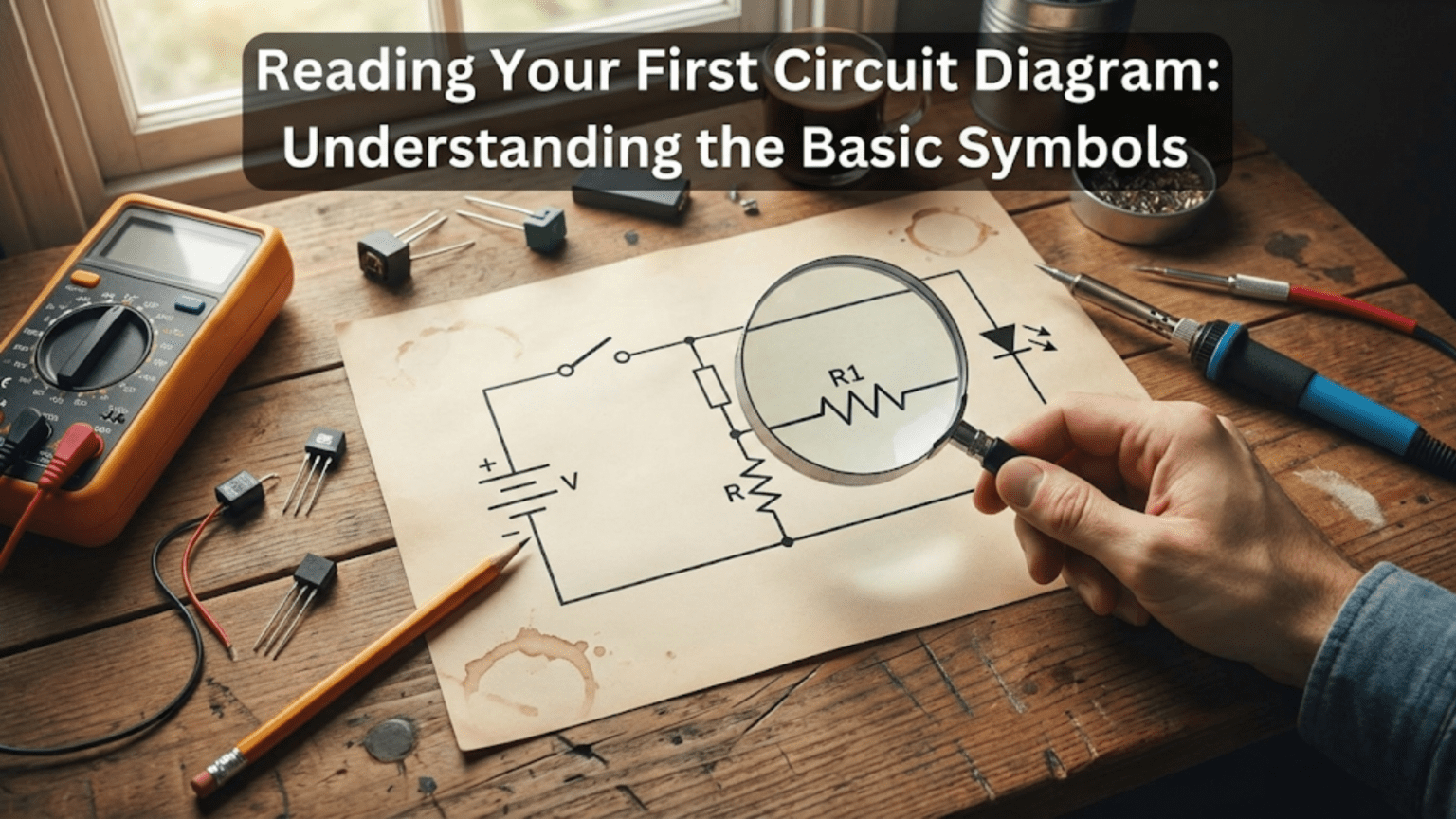

Introduction

Circuit diagrams, also called schematics, represent one of the most powerful tools in electronics. These visual representations communicate complex electrical relationships through standardized symbols and conventions, enabling engineers, technicians, and hobbyists worldwide to share designs, understand existing circuits, and troubleshoot problems regardless of language barriers. Yet for beginners encountering their first schematic, these diagrams can appear as cryptic collections of strange symbols connected by lines, more resembling hieroglyphics than useful technical documentation.

The ability to read circuit diagrams is not optional for anyone serious about electronics. Every electronics textbook uses schematics to explain concepts. Every kit you might build includes a schematic. Every piece of equipment you might repair has a schematic as part of its service documentation. When asking for help troubleshooting a circuit, you will need to reference or sketch a schematic. When designing your own circuits, you will think in schematics. This fundamental skill underlies virtually all other electronics competencies.

This comprehensive guide will transform circuit diagrams from incomprehensible abstractions into clear, readable technical documents. We will start with the most basic concepts of what schematics represent and why they use particular conventions, then systematically build your symbol vocabulary while developing practical skills for interpreting real schematics. Rather than merely memorizing symbols, you will understand the logic behind schematic conventions and develop intuition for reading circuits that serves you throughout your electronics journey.

What Circuit Diagrams Represent

Before diving into specific symbols, understanding what information circuit diagrams convey and what they intentionally omit helps you approach them with appropriate expectations.

The Conceptual Map

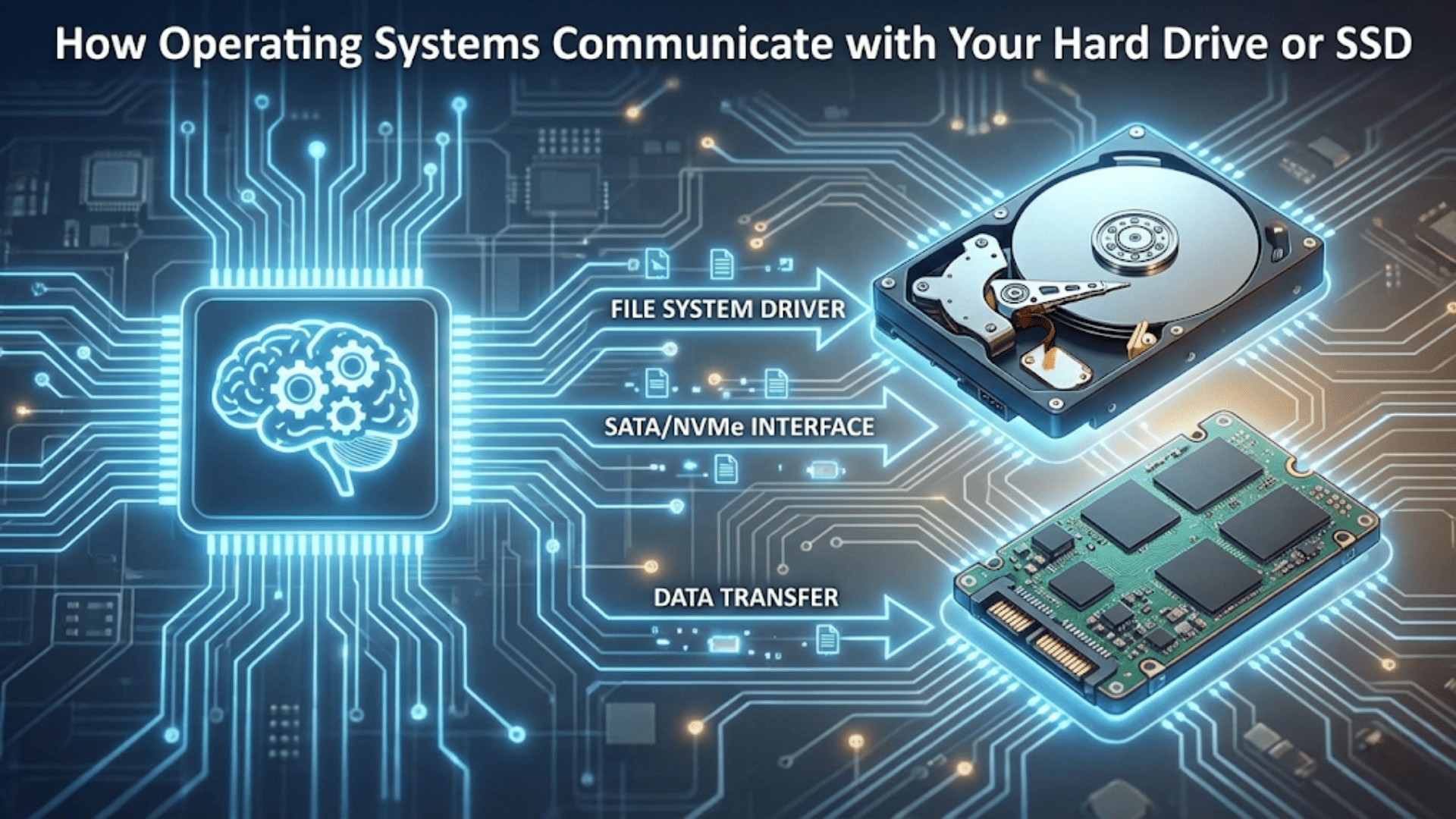

A circuit diagram is a conceptual map of electrical connections, not a physical layout drawing. The schematic shows which component terminals connect to which other terminals, how current flows through the circuit, and what voltage relationships exist between different points. It does not show the physical size of components, their exact placement, the routing of wires, or what the finished circuit looks like.

This abstraction from physical reality serves an important purpose. By removing physical details and presenting only electrical relationships, schematics focus attention on circuit function rather than construction details. A schematic shows you that a resistor connects between the positive power supply and an LED, with the LED connecting to ground. Whether that resistor is physically above, below, or beside the LED in the actual circuit is irrelevant to understanding circuit function, so the schematic omits that information.

Think of a circuit diagram as similar to a subway map. The subway map shows which stations connect to which lines and where transfers are possible, but it does not show actual geographic locations, tunnel routing, or distances. Just as the subway map serves its purpose of helping passengers plan routes without geographic accuracy, circuit diagrams serve their purpose of showing electrical connections without physical accuracy.

What Schematics Show

Circuit diagrams explicitly show several critical types of information. They show every electrical connection between components, typically represented as lines connecting component symbols. They show component types through standardized symbols—a zigzag line for a resistor, a pair of parallel lines for a capacitor, and so on. They show component values or part numbers through labels adjacent to component symbols.

Schematics show power supply connections, ground connections, and voltage levels at important points. They show signal flow direction through conventions like left-to-right signal progression in audio circuits or input-to-output orientation in logic circuits. They show switch positions, transistor types, integrated circuit pin numbers, and other details necessary to understand or build the circuit.

What Schematics Do Not Show

Circuit diagrams intentionally omit physical details that are irrelevant to electrical function. They do not show wire lengths, wire routing paths, component physical sizes, or physical relationships between components. A tiny surface-mount resistor and a large power resistor both use the same symbol; the schematic does not distinguish their physical size.

Schematics generally do not show wire colors, mechanical mounting details, thermal considerations, or electromagnetic interference shielding—though specialized schematics for specific purposes might include some of these details. The standard circuit diagram focuses purely on electrical relationships, leaving mechanical and physical implementation details to other documentation like PCB layouts, mechanical drawings, and assembly instructions.

This abstraction means you cannot build a circuit from a schematic alone without making decisions about physical implementation. The schematic tells you what connects to what electrically, but you must decide wire gauges, component placement, mounting methods, and enclosure requirements based on the application, available components, and construction methods.

Basic Schematic Conventions

Circuit diagrams follow conventions that make them easier to read once you understand the patterns. These conventions are not arbitrary but reflect decades of evolution toward clarity and standardability.

Signal Flow and Orientation

By convention, schematics typically organize components so signal flow proceeds from left to right and power flows from top to bottom. Input connections appear on the left side of the schematic, outputs on the right. Power supply connections appear at the top, ground connections at the bottom. This convention is not universal—some circuits cannot naturally organize this way—but it appears often enough that recognizing it helps you quickly grasp circuit function.

Following this convention, when you see a schematic, instinctively look to the left for where signals enter the circuit and trace rightward to see how those signals are processed and where they exit. Look to the top to find power supply voltages and downward to find ground returns. This systematic approach helps you navigate schematics efficiently.

Connection Representation

Lines in schematics represent electrical connections, typically wires or PCB traces. When two lines cross in a schematic, they may or may not connect depending on how the crossing is drawn. A connection is indicated by a dot where lines meet—any time you see a dot where lines intersect, those lines are electrically connected. When lines cross without a dot, they do not connect; they simply pass over each other with no electrical contact.

Older schematics sometimes showed non-connecting crossovers with a small semicircular hump where one line jumped over the other, making it obvious they did not connect. Modern practice uses the dot convention, placing dots only where connections occur. If you see lines intersecting without a dot, assume they do not connect. This convention prevents ambiguity that could arise if dots were required for both connections and non-connections.

Some drafting styles show four-way connections (where four lines meet at a point) as four separate two-way connections with three dots, while others show a single dot where all four lines meet. Both approaches are valid; what matters is that dots clearly indicate intentional connections while line crossings without dots indicate no connection.

Component Labels and Reference Designators

Each component in a schematic receives a reference designator, a unique identifier consisting of a letter or letters indicating component type followed by a number. Resistors use R (R1, R2, R3, etc.), capacitors use C (C1, C2, etc.), transistors use Q (Q1, Q2, etc.), diodes use D, integrated circuits use U or IC, inductors use L, transformers use T, and so forth. These reference designators let you unambiguously refer to specific components when discussing circuits or following assembly instructions.

Component values appear near their symbols, using standard abbreviations and multipliers. Resistors show values in ohms (100Ω, 1kΩ, 1MΩ). Capacitors show values in farads with metric prefixes (100pF, 1µF, 100µF). Voltage and power ratings may appear where relevant to component selection. Component tolerance might be specified for critical components.

Power and Ground Symbols

Rather than drawing explicit wires connecting every component to power supply and ground, schematics use special symbols that implicitly represent these connections. A ground symbol at any location represents connection to the circuit’s reference point, typically the negative terminal of the power supply in DC circuits. Multiple ground symbols throughout a schematic all represent the same electrical point—they are all connected together even though no line explicitly connects them.

Similarly, power supply symbols (often an arrow pointing upward, or a circle with voltage labeled) represent connection to the positive power supply rail. All components connected to power symbols marked “+12V” connect to the same +12V supply even without explicit connecting wires. This convention dramatically reduces visual clutter in schematics by eliminating the dozens or hundreds of wires that would otherwise need to be drawn to show power and ground connections.

Essential Component Symbols

Building your symbol vocabulary begins with the most common components you will encounter in basic circuits. These fundamental symbols appear in the vast majority of schematics.

Resistors

The resistor symbol consists of a zigzag line in American schematics or a simple rectangle in European/international schematics. Both represent the same component—a device that opposes current flow with a specific resistance value. The resistor symbol is always the same regardless of resistor type (carbon film, metal film, wirewound, etc.) or power rating. The schematic focuses on the electrical characteristic (resistance value) rather than physical implementation details.

Variable resistors, also called potentiometers or rheostats, use the standard resistor symbol with an arrow pointing to it, indicating the resistance can be adjusted. The arrow typically points to the center of the resistor symbol. A three-terminal potentiometer might show all three terminals explicitly, or might show two terminals with the arrow representing the wiper connection.

Thermistors, resistors whose value changes with temperature, use the resistor symbol with a small temperature symbol (often a t or θ) nearby. Photoresistors, whose resistance changes with light, use the resistor symbol with light ray arrows pointing toward it. These specialized symbols communicate that resistance varies with environmental conditions rather than being fixed.

Capacitors

Capacitors use a symbol consisting of two parallel lines, representing the physical structure of two conductive plates separated by an insulator. Non-polarized capacitors (ceramic, film, etc.) use two identical parallel lines. Polarized capacitors (electrolytic, tantalum) use one straight line and one curved line, with the curved line representing the negative terminal. This distinction is critical because connecting polarized capacitors backward can destroy them or cause explosions.

Variable capacitors use the parallel lines with an arrow pointing to them, similar to variable resistors. Trimmer capacitors, small adjustable capacitors set once during circuit setup, might use a similar symbol or might include additional notation indicating they are trimmers rather than continuously adjustable variables.

The capacitor symbol always looks similar regardless of capacitor type, voltage rating, or size. A tiny 10pF ceramic capacitor and a huge 10,000µF electrolytic capacitor use essentially the same symbol. The value label distinguishes them electrically; component selection for physical implementation happens later.

Inductors

Inductors use a symbol showing a series of curves or loops, representing the coiled wire structure of real inductors. The number of loops in the symbol does not indicate the actual number of turns in the inductor—the symbol is a stylized representation, not a literal depiction. Some schematics show inductors as three or four curves, others as two or five; the specific number of curves does not matter as long as the coiled shape is recognizable.

Iron-core inductors might include a pair of parallel lines running through the center of the coil symbol, representing the ferromagnetic core that increases inductance. Air-core inductors use the plain coil symbol without any core indication. Variable inductors show the coil symbol with an arrow, similar to variable resistors and capacitors.

Transformers, which are essentially two or more inductors magnetically coupled together, show multiple coil symbols positioned parallel to each other with parallel lines between them representing the magnetic core. The dots appearing on transformer coil symbols indicate phase relationships—current entering a dotted terminal in one coil induces voltage that makes the dotted terminal of another coil positive.

Diodes

Diodes use a symbol consisting of a triangle pointing toward a line, representing the unidirectional current flow characteristic of diodes. Current flows in the direction the triangle points—from anode (the non-bar end) to cathode (the bar end). The triangle can be thought of as an arrow showing allowed current direction, while the bar represents the barrier blocking reverse current.

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) use the standard diode symbol with small arrows pointing away from the symbol, representing emitted light. Photodiodes use the diode symbol with arrows pointing toward it, representing incoming light that generates current. Zener diodes, used for voltage regulation, use the diode symbol with a modified bar that has small lines extending from its ends, creating a shape resembling a capital Z on its side.

Different diode types use variations of the basic triangle-and-bar symbol, but all are recognizable as diodes once you learn the basic symbol. The key insight is that the triangle and bar convey the fundamental diode characteristic: current flows easily one direction (the direction the triangle points) and is blocked in the reverse direction (stopped by the bar).

Transistors

Transistor symbols are more complex because they represent three-terminal devices with multiple types. Bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) use symbols showing a vertical line with two angled lines extending from it. An arrow on one of the angled lines indicates transistor type and emitter terminal. For NPN transistors, the arrow points away from the vertical line (remembering “NPN: Not Pointing iN” helps). For PNP transistors, the arrow points toward the vertical line.

The three terminals are emitter (the one with the arrow), collector (the other angled line), and base (the connection point on the vertical line). Understanding which terminal is which is essential because transistors only function when connected correctly. The arrow always appears on the emitter terminal, making it easy to identify.

Field-effect transistors (FETs) use different symbols reflecting their different operating principles. MOSFETs show a vertical line representing the gate, with three short lines parallel to it representing drain, source, and substrate. The symbol variations for enhancement-mode vs. depletion-mode and N-channel vs. P-channel MOSFETs communicate important operating differences. JFETs use similar symbols but with the gate connection physically touching the channel line.

Integrated Circuits

Integrated circuits are typically represented as simple rectangles or triangles with pins along the sides. The rectangle is labeled with the IC type (LM358, 555, ATmega328, etc.) and pin numbers appear next to each connection point. The schematic shows how the IC connects to other components but does not show the complex circuitry inside the IC—that internal complexity is abstracted away.

Operational amplifiers commonly use a triangular symbol with two inputs on the left (one marked + for non-inverting input, one marked – for inverting input) and one output on the right. Power supply connections may be shown or may be implicit. Logic gates use distinctive symbols for each gate type—AND gates use a shape resembling a D, OR gates use a curved shape, NOT gates use a triangle with a small circle, and so forth.

The IC symbol’s simplicity reflects schematic philosophy: show electrical connections and function without detailing internal implementation. You do not need to understand the thousands or millions of transistors inside an IC to use it correctly in a circuit; you only need to know what each pin does and how to connect it.

Switches

Switches use symbols showing a movable element that completes or breaks a connection. A simple single-pole single-throw (SPST) switch shows two terminals with a line that can pivot to connect or disconnect them. Single-pole double-throw (SPDT) switches show three terminals with a movable connection that can connect to either of two fixed contacts.

More complex switches like rotary selectors or pushbuttons use more elaborate symbols, but they all follow the principle of showing movable elements that make or break connections. The switch symbol’s mechanical appearance, showing physical movement, differs from most other symbols that are more abstract representations of electrical function.

Relays combine a coil symbol (inductor) with switch contacts, showing both the control side (energizing coil) and the switching side (contacts that move when coil energizes). A relay symbol makes explicit that energizing the coil mechanically moves contacts, though in actual relays this happens electromagnetically inside a sealed enclosure.

Power Sources

Batteries use a symbol showing alternating long and short parallel lines, representing the series connection of multiple cells. A simple cell uses one long line and one short line. Multi-cell batteries show multiple pairs of long and short lines. The long line represents the positive terminal, the short line represents the negative terminal. This convention makes polarity obvious at a glance.

AC voltage sources use a circle with a sine wave inside, representing the alternating nature of the output. DC power supplies might use a circle with +/- symbols, or might simply use voltage labels on power rails. The specific symbol matters less than the voltage label; what is important is knowing what voltage appears at that point in the circuit.

Ground symbols come in several variations but all represent the zero-volt reference point. A common ground symbol shows a single horizontal line with three progressively shorter lines below it, creating a shape resembling an upside-down Christmas tree. Earth ground uses a symbol showing three horizontal lines of decreasing length. Chassis ground shows a different symbol still. Understanding which type of ground is present matters in some contexts, particularly when dealing with safety and grounding issues.

Reading Circuit Topology

Beyond recognizing individual symbols, understanding how components connect reveals circuit function and behavior. Circuit topology—the pattern of connections—often reveals circuit purpose and operating principles.

Series Connections

When components connect end-to-end with no branches, they form a series circuit. Current must flow through each component in sequence. In schematics, series connections appear as components placed along a single continuous path. A voltage divider showing two resistors in series, with the junction between them providing a divided voltage, represents a common series topology.

Recognizing series connections helps you immediately understand that the same current flows through all series components. This insight allows quick calculations using Ohm’s Law and series resistance rules. It also alerts you to the vulnerability of series circuits—breaking the connection anywhere stops current everywhere.

Parallel Connections

When components connect to the same two points, providing multiple simultaneous current paths, they form parallel connections. In schematics, parallel components often appear physically parallel, though this is not required. The defining characteristic is that all parallel components share the same voltage across their terminals.

Parallel topology appears when multiple LEDs connect to the same voltage source, when filter capacitors connect across power supply rails, or when resistors connect to divide current. Recognizing parallel connections tells you that voltage is identical across all parallel elements while current divides among them based on their relative impedances.

Series-Parallel Combinations

Most practical circuits combine series and parallel elements in various ways. Learning to recognize which components are in series with each other and which are in parallel develops through practice. Look for points where current can split (parallel branches begin) and points where branches rejoin (parallel branches end). Identify sections where current has only one path (series elements).

Breaking complex circuits into series and parallel sections simplifies analysis. Calculate the equivalent resistance of parallel sections, then treat that equivalent as a single component in series with other elements. Systematically simplifying circuits reveals their fundamental behavior even when they initially appear complex.

Common Circuit Blocks

Certain arrangements of components appear repeatedly because they perform useful functions. Learning to recognize these common blocks helps you quickly understand circuit function. A voltage divider (two resistors in series) provides a reduced voltage. A low-pass filter (resistor in series with capacitor to ground) blocks high frequencies while passing low frequencies. A current source (transistor with emitter resistor) provides constant current independent of load resistance.

As you gain experience reading schematics, you will begin recognizing these functional blocks automatically. A quick glance reveals “that’s a voltage regulator,” “that’s a differential amplifier,” or “that’s a resonant filter” without needing to analyze individual components. This pattern recognition dramatically speeds schematic comprehension.

Practical Schematic Reading Skills

Reading schematics effectively requires systematic approaches that help you extract information efficiently and accurately.

Starting Point Selection

When confronting a new schematic, where you begin matters. For circuits with clear inputs and outputs, start at the input and trace signal flow toward the output. For power supplies, start at the AC input and follow power conversion through rectification, filtering, and regulation to the DC output. For control circuits, start at the sensor or control input and follow logic through to the actuator or output.

Starting at power and ground connections often provides useful context. Identify supply voltages, verify ground symbols, and understand what voltage levels exist in different circuit sections. This establishes the voltage domain in which the circuit operates and helps you interpret component values appropriately.

Signal Tracing

Follow signal paths through the circuit, identifying what each stage does to the signal. Does this stage amplify? Filter? Compare to a reference? Convert from one form to another? Understanding the transformation occurring at each stage reveals overall circuit function even if you do not understand every detail of implementation.

When tracing signals, mark the schematic with colored pencils or highlighters if working with paper copies, or use electronic markup tools for digital schematics. Different colors for different signals helps visualize signal flow and identify where signals merge or split.

Critical Component Identification

Certain components in any circuit are more critical than others for understanding circuit function. Identify active components (transistors, op-amps, ICs) that actually process signals. These components determine what the circuit does; passive components (resistors, capacitors) typically bias active components or filter signals but do not fundamentally change circuit function.

Identifying feedback paths where outputs connect back to inputs reveals whether the circuit is stable or unstable, whether it might oscillate, and how it responds to changes. Feedback dramatically affects circuit behavior; recognizing feedback paths is essential for understanding circuit function.

Reference Information Usage

Many schematics include additional information beyond the circuit diagram itself. Title blocks identify circuit function, designer, date, and revision. Notes clarify unusual design decisions or specify critical adjustments. Tables list parts with manufacturer part numbers and specifications. Use this supplementary information to fully understand the circuit.

When components are specified by part number rather than generic type, look up datasheets to understand component characteristics. A component labeled “2N3904” does not tell you much without knowing that is a general-purpose NPN transistor with specific voltage and current ratings. Datasheet research turns part numbers into meaningful information about circuit capabilities and limitations.

Simulation Before Building

Before building a circuit from a schematic, simulate it using circuit simulation software like LTspice, CircuitLab, or similar tools. Simulation reveals whether the circuit functions as intended, what voltages and currents exist at various points, and how the circuit responds to different inputs. Simulation is much faster and cheaper than building physical prototypes, and it reveals problems before you risk destroying components.

Simulation also deepens schematic understanding. Probing voltages and currents at various nodes while observing how they change with different inputs teaches circuit behavior more effectively than static schematic reading. The interactive nature of simulation accelerates learning.

Common Mistakes and Misinterpretations

Beginners make predictable mistakes when learning to read schematics. Understanding these common errors helps you avoid them.

Assuming Physical Layout Matches Schematic

The most common beginner mistake is assuming the schematic shows physical component arrangement. Remember: schematics are electrical maps, not physical layouts. Components far apart on the schematic might be physically adjacent. Components adjacent on the schematic might be physically separated. The schematic shows electrical connections; PCB layouts or mechanical drawings show physical arrangements.

This mistake causes particular confusion when trying to build circuits on breadboards or perfboard from schematics. You must translate the schematic’s electrical information into a physical layout that makes sense for your construction method. This translation is a separate design step beyond schematic reading.

Misinterpreting Crossing Lines

Confusion about whether crossing lines connect or not causes frequent errors. Apply the dot rule consistently: dots indicate connections, lack of dots indicates no connection. When reading older schematics that might use different conventions, verify the meaning by checking obviously connected points (like both terminals of a component connecting to other circuit elements) and obviously unconnected points (like separate power and signal traces).

If unclear whether a schematic uses consistent dot conventions, trace suspected connections to see if they make electrical sense. A line appearing to connect ground and positive supply without intervening components is almost certainly a drafting error or an artifact of line crossing without actual connection.

Overlooking Implicit Connections

Power and ground symbols create implicit connections throughout the schematic. Beginners sometimes fail to realize that every ground symbol connects to every other ground symbol even without visible connecting lines. This oversight leads to incomplete understanding of current paths and confusion about how circuits function.

Similarly, power supply symbols labeled with the same voltage all represent the same electrical point. All +5V symbols connect together, all +12V symbols connect together, and so on. The schematic does not need to show actual wires because the labeled symbols convey the connections implicitly.

Ignoring Component Values

Component symbols show component type, but component values determine circuit behavior. Two resistors in series might use identical symbols, but if one is 100Ω and the other is 10kΩ, they behave very differently as a voltage divider than if both were 1kΩ. Always note component values; they are as important as connection topology.

Similarly, voltage and current ratings matter greatly for real circuits even if they do not affect simulated behavior. A capacitor symbol does not show whether that capacitor is rated for 10V or 100V, but using a 10V capacitor in a 50V circuit leads to destructive failure. Check component ratings, not just values.

Expecting Perfect Correspondence with Physical Circuits

Real circuits sometimes differ slightly from schematics due to engineering changes not reflected in documentation, manufacturing variations, or undocumented modifications. When troubleshooting actual equipment, verify that physical circuits match schematics before trusting schematic information completely. Component values may have changed, jumper wires may have been added, or substitutions may have been made.

This does not mean schematics are unreliable—they usually reflect actual circuits accurately—but healthy skepticism and physical verification prevent time wasted troubleshooting perceived schematic problems that are actually documentation errors or undocumented modifications.

Advanced Schematic Features

As you progress beyond basic schematics, you will encounter additional conventions and features that convey more sophisticated information.

Subcircuits and Hierarchical Design

Complex circuits often use hierarchical design where functional blocks appear as single symbols in high-level schematics, with detailed implementation shown in separate subcircuit schematics. This hierarchical approach manages complexity by allowing you to understand high-level function without immediately confronting every implementation detail.

When encountering hierarchical schematics, start with the top-level diagram to understand overall function and signal flow. Then drill down into subcircuits as needed to understand specific sections. This top-down approach is more effective than trying to understand every detail immediately.

Bus Notation

When many signals follow parallel paths, schematics sometimes use bus notation where a single thick line with a slash and number represents multiple parallel conductors. A bus marked “8” represents eight parallel signal lines. This notation dramatically simplifies schematics for microprocessor circuits or other designs with many parallel data or address lines.

Individual signals within a bus may be labeled (D0-D7 for an eight-bit data bus) and may be shown individually where they connect to specific components. The bus notation appears only in sections where all signals follow the same path, expanding to individual lines where signals separate.

Test Points and Measurement Locations

Schematics for production equipment or test fixtures often include test point symbols showing where measurements should be taken during troubleshooting or verification. These test points might indicate expected voltage levels, waveform characteristics, or other diagnostic information. When troubleshooting equipment, check test points first to quickly identify which circuit section contains the fault.

Net Names and Numbered Connections

Complex schematics might label connections with net names or numbers that identify electrically equivalent points throughout multi-page schematics. All points labeled “RESET” or all points marked with net number “47” are connected together even if no visible line connects them. This convention simplifies complex schematics by eliminating many long connecting lines that would clutter the diagram.

Developing Schematic Reading Fluency

Like learning to read any language, developing fluency in reading schematics requires practice and exposure to many examples.

Deliberate Practice

Regularly study schematics for circuits in your areas of interest. When reading electronics articles or project descriptions, always examine the schematic carefully even if the article includes a PCB layout or physical construction guide. Translate physical layouts back to schematics mentally, identifying which schematic elements correspond to which physical components.

Redraw schematics by hand to internalize symbol conventions and connection patterns. The physical act of drawing reinforces learning more effectively than passive reading. Redrawing also reveals aspects of schematics you might have overlooked when merely reading them.

Progressive Complexity

Start with simple schematics for single-stage circuits: voltage dividers, LED drivers, simple amplifiers. Progress to multi-stage circuits: audio amplifiers, power supplies, radio receivers. Eventually tackle complex schematics for microprocessor systems, communication equipment, or sophisticated instrumentation. This gradual progression builds confidence and competence without overwhelming you.

Each schematic you study teaches you something: a new component you had not encountered, a connection pattern you had not seen, a design technique you had not imagined. This accumulated knowledge makes subsequent schematics easier to understand because you recognize more patterns and need to learn fewer new concepts per schematic.

Analyzing Rather Than Just Reading

Move beyond passively reading schematics to actively analyzing them. Ask yourself: Why did the designer choose these component values? What happens if I change this resistor? What is the frequency response of this filter? How much current flows here? This active analysis develops deeper understanding than simply identifying components and connections.

Perform calculations on schematics you study. Calculate voltage drops, current flows, power dissipation, frequency response, and other characteristics. Compare calculated values to typical specifications or expected behavior. This quantitative analysis transforms passive schematic reading into active circuit understanding.

Using Multiple Resources

Different resources present schematics with different drafting conventions and at different complexity levels. Study schematics from multiple sources: textbooks, kit instructions, open-source projects, commercial equipment service manuals, and application notes. This exposure to varied presentation styles makes you fluent in reading any schematic you encounter rather than only those formatted in familiar ways.

Compare schematics for circuits performing similar functions. How do different designers solve the same problem? What tradeoffs did they make? What components did they emphasize? This comparative analysis reveals design principles and alternative approaches that broaden your understanding beyond any single schematic.

Conclusion: The Universal Language of Electronics

Circuit diagrams represent the universal language through which electronics knowledge is communicated, preserved, and shared. While spoken languages differ among peoples and nations, schematic symbols and conventions maintain remarkable consistency worldwide. An engineer in Japan, a technician in Brazil, and a hobbyist in Norway can all understand the same schematic despite speaking different languages, because schematic symbols transcend linguistic barriers.

Learning to read schematics fluently opens the entire accumulated knowledge base of electronics to you. Every published circuit becomes accessible. Every service manual becomes comprehensible. Every design becomes a learning opportunity. This skill amplifies your electronics capabilities enormously, transforming you from someone who can only follow explicit step-by-step instructions to someone who can understand and create circuits independently.

The journey from beginner confusion to confident schematic reading takes time and practice. Initially, every schematic seems like an incomprehensible puzzle. With exposure and study, individual symbols become recognizable. Connection patterns become clear. Circuit functions become apparent. Eventually, you reach the point where you can glance at a schematic and immediately grasp its purpose, signal flow, and key design decisions. This fluency marks a major milestone in your electronics education.

Remember that even experienced engineers occasionally encounter unfamiliar symbols or conventions. The difference is that they know how to research unknown elements, how to infer meaning from context, and how to systematically analyze unfamiliar circuits. These meta-skills—knowing how to learn what you do not know—matter as much as the specific symbol vocabulary you have memorized.

As you continue your electronics journey, make schematic reading a regular practice. Study schematics for circuits you build. Draw schematics for your own designs. Analyze schematics from equipment you own or use. Explain schematics to others, which reinforces your own understanding. This consistent practice maintains and deepens your schematic fluency, ensuring this essential skill remains sharp and continues developing throughout your electronics career.

The symbols and conventions you have learned here form the foundation, but schematic reading is ultimately about understanding electrical relationships, recognizing functional patterns, and extracting design intent from abstract diagrams. These higher-level skills develop through extensive practice and active engagement with many schematics. Each schematic you study adds to your pattern library and deepens your intuition for how circuits work. Embrace this learning process, and you will find that circuit diagrams transform from obstacles into powerful tools that accelerate your electronics mastery.