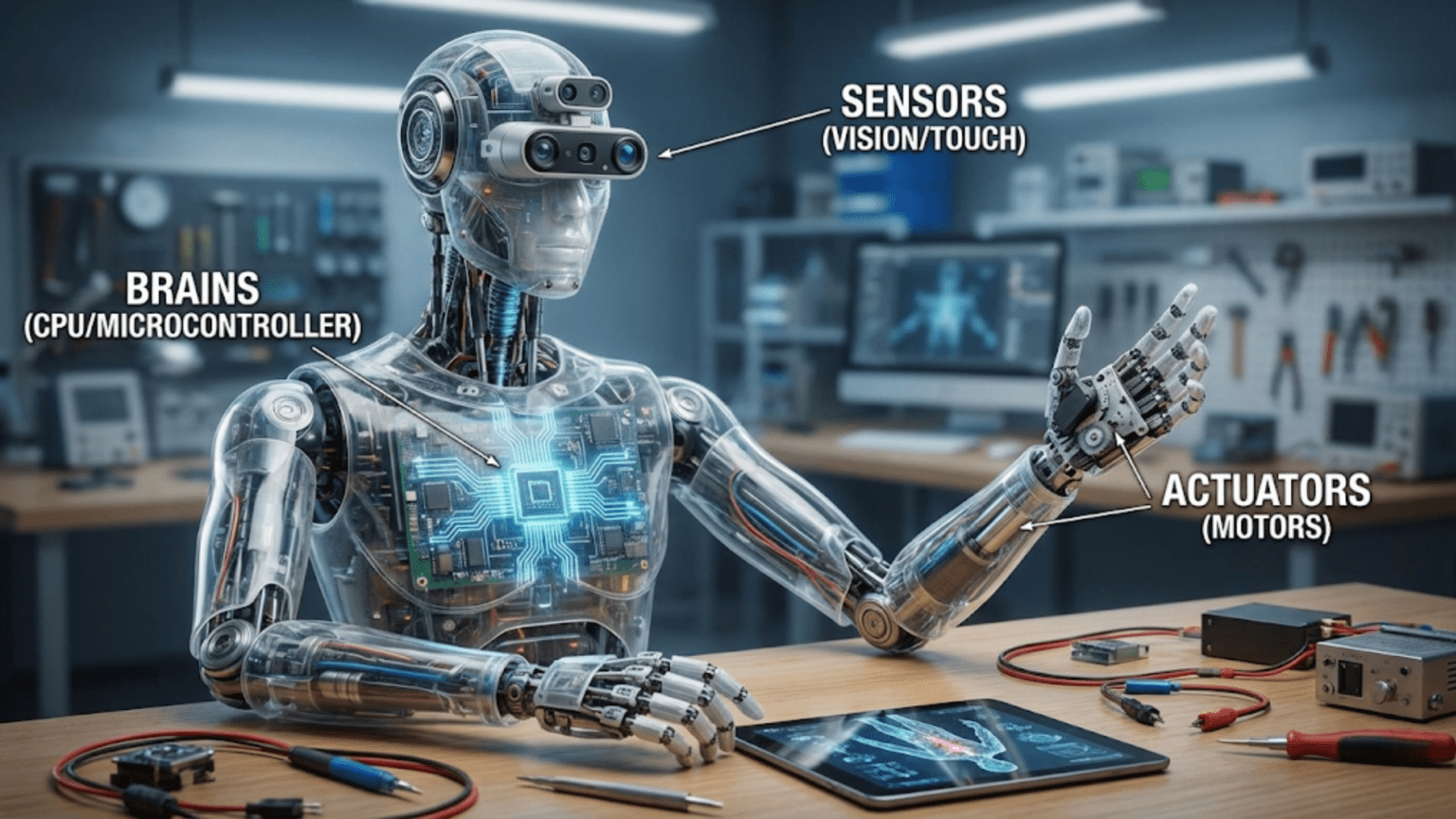

When biologists study living organisms, they examine anatomy to understand how different body parts work together to create life. The heart pumps blood, lungs exchange gases, muscles contract to produce movement, and the brain coordinates everything. This anatomical framework helps us comprehend complex biological systems by breaking them into functional components. Robotics benefits from a similar anatomical perspective, where we can examine the essential components that work together to create robotic behavior. While robots differ fundamentally from biological organisms, understanding their anatomy through the lens of actuators, sensors, and brains provides a clear mental model for how these machines function.

This anatomical framework simplifies the overwhelming complexity you encounter when first examining a robot. Instead of seeing a confusing tangle of wires, motors, circuit boards, and mechanical parts, you can identify three functional categories that every robot possesses. The actuators serve as muscles, creating movement and physical action. The sensors function like sensory organs, gathering information about the environment and the robot’s own state. The brain, typically a microcontroller or computer, processes sensory information and commands the actuators, much like biological nervous systems coordinate body functions. Understanding these three components and how they interconnect gives you the foundation for analyzing any robot you encounter and designing your own robotic systems.

This article examines each of these anatomical components in detail, explaining what they do, how they work, and how they fit into the larger robotic system. You will discover the variety of options within each category, learn to recognize them in actual robots, and understand the design choices that determine which specific actuators, sensors, and brains suit different applications. This anatomical understanding transforms robotics from a mysterious black box into a comprehensible system where each component serves clear purposes within an integrated whole.

Actuators: The Muscles of Robots

Actuators represent the robot’s ability to affect the physical world through movement and force. Just as biological muscles contract to move limbs, open jaws, or pump blood, robot actuators convert electrical energy into mechanical motion that drives wheels, rotates joints, opens grippers, or activates other mechanisms. Without actuators, a robot would be paralyzed, able to sense and think but unable to act on its decisions. The variety, power, and precision of a robot’s actuators fundamentally determine what physical tasks it can accomplish.

Electric motors form the most common actuator type in modern robotics, converting electrical current into rotational motion through electromagnetic principles. When current flows through coils of wire in a magnetic field, the resulting forces cause rotation. This simple principle scales from tiny motors smaller than a fingernail to massive industrial motors weighing hundreds of kilograms. The universal nature of electric motors, combined with their reliability, controllability, and wide performance range, makes them the default choice for most robotic applications.

Different motor types suit different applications based on their performance characteristics. Brushed DC motors, the simplest electric motor type, use mechanical brushes to switch current direction as the motor rotates. These motors cost little, control easily through simple voltage variation, and provide substantial torque at reasonable speeds. However, the brushes wear out over time and create electrical noise that can interfere with sensitive electronics. Hobbyist robots and simple projects often use brushed DC motors because they work well for basic applications and remain inexpensive.

Brushless DC motors eliminate mechanical brushes by using electronic switching instead, improving efficiency, lifespan, and power-to-weight ratio compared to brushed motors. The lack of brushes also eliminates a wear component and reduces electrical noise. However, brushless motors require more sophisticated electronic speed controllers to manage the switching. Drones, high-performance robots, and electric vehicles increasingly use brushless motors where efficiency and performance justify the increased complexity and cost.

Servo motors integrate a DC motor with position feedback and control electronics in a single package. When you command a servo to move to a specific angle, its internal electronics drive the motor until feedback from a potentiometer or encoder confirms the desired position has been reached. This position control makes servos ideal for robotic joints that must move to and hold precise angles. Hobby servos designed for radio-controlled models provide affordable, easy-to-use actuation for educational and hobbyist robots. More sophisticated servos used in professional robotics offer greater precision, higher torque, and advanced features like compliance control and networked communication.

Stepper motors move in discrete steps rather than continuous rotation, advancing a fixed angle with each electrical pulse. A typical stepper might move 1.8 degrees per step, requiring 200 steps for a complete rotation. This discrete motion allows precise positioning without feedback sensors, since counting pulses tells you exactly how far the motor has rotated. Stepper motors excel in applications like 3D printers and CNC machines where precise, repeatable positioning matters more than speed or efficiency. The stepwise motion makes them less suitable for smooth, fast motion but perfect for controlled, incremental movement.

Linear actuators extend or retract rather than rotating, creating straight-line motion directly without needing wheels or linkages to convert rotation. Some linear actuators use lead screws, where a rotating motor turns a threaded rod that moves a nut linearly. Others use hydraulic or pneumatic cylinders where fluid pressure extends or retracts a piston. Electric linear actuators provide precise position control, while hydraulic and pneumatic types offer very high force output for heavy-duty applications. Robotic systems requiring linear motion, like extending arms or pushing mechanisms, often employ linear actuators to simplify mechanical design.

Beyond rotating and linear actuators, specialized types serve specific needs. Piezoelectric actuators use materials that deform when voltage is applied, creating extremely small, precise movements useful for microscale positioning. Shape memory alloy wires contract when heated by electrical current, providing lightweight actuation that returns to original length when cooled. Artificial muscles using pneumatic or hydraulic pressure in flexible materials create compliant, lifelike motion. While less common than conventional motors, these alternative actuators enable capabilities difficult to achieve with traditional approaches.

Actuator selection requires balancing competing requirements. Torque, the rotational force an actuator produces, determines how much load it can move. Speed indicates how quickly it rotates or extends. Power consumption affects battery life and heat generation. Size and weight constrain where actuators fit and how they affect robot balance. Cost influences how many actuators you can afford. No single actuator optimizes all these factors, so choosing actuators involves prioritizing what matters most for your specific application.

Gearing modifies actuator performance by trading speed for torque or vice versa. A gearbox between motor and output shaft can reduce speed while multiplying torque, letting a small, fast motor drive heavy loads slowly. Alternatively, gearing can increase speed while reducing torque for applications needing rapid but light motion. Understanding gear ratios and mechanical advantage helps you match available motors to the torque and speed your robot actually needs.

Sensors: The Sensory Organs of Robots

While actuators give robots the ability to act, sensors provide the perceptual awareness that makes actions meaningful and responsive. A robot operating in the real world must gather information about its surroundings, its own configuration, and relevant environmental conditions. Sensors convert physical phenomena into electrical signals the robot’s brain can process, creating digital representations of the analog world. The sophistication and appropriateness of a robot’s sensors fundamentally shape what it can perceive and therefore what behaviors it can exhibit.

Proprioceptive sensors tell the robot about its own body state, similar to how biological proprioception lets you know where your limbs are without looking at them. Encoders measure rotational position of motors and joints, reporting how many degrees a joint has rotated or how many wheel revolutions have occurred. This feedback allows precise motion control and odometry calculations that estimate how far the robot has traveled based on wheel rotations. Incremental encoders report changes in position, while absolute encoders directly measure actual position even after power loss.

Current sensors measure electrical current flowing to motors, providing indirect force feedback. When a motor encounters increased load, it draws more current to maintain motion. Monitoring this current tells the robot about interaction forces without dedicated force sensors. If current suddenly spikes, the robot might be colliding with an obstacle or trying to move a jammed mechanism. Current sensing enables protective behaviors that prevent damage from overload conditions while also providing awareness of interaction forces during manipulation tasks.

Inertial measurement units combine accelerometers and gyroscopes to measure acceleration and rotation. Accelerometers detect linear acceleration in multiple axes, revealing both motion and tilt relative to gravity. Gyroscopes measure rotational velocity around different axes. Fusing data from both sensor types allows calculating orientation and tracking motion even when visual or other external references are unavailable. Smartphones use IMUs to detect screen rotation, while drones use them for stabilization, and mobile robots employ them for navigation.

Exteroceptive sensors perceive the external environment beyond the robot’s own body. Distance sensors including ultrasonic, infrared, and laser rangefinders measure how far away objects sit, enabling obstacle detection and avoidance. These sensors emit signals and measure reflections or time-of-flight to calculate distances. Different technologies suit different ranges, precision requirements, and environmental conditions. Understanding their characteristics helps you select appropriate distance sensing for your robot’s needs.

Vision sensors, primarily cameras, capture rich visual information about the environment. A camera frame contains millions of pixels encoding color and brightness, providing far more information than most other sensor types. This data enables object recognition, navigation using visual landmarks, reading text, detecting motion, and countless other perceptual tasks. However, extracting useful information from camera images requires substantial processing, making vision both powerful and computationally demanding. Specialized cameras like depth cameras, thermal imagers, or event-based cameras provide different types of visual information suited to particular applications.

Contact sensors detect physical interaction through touch. Simple mechanical switches close when pressed, providing binary contact detection. Force-sensitive resistors measure contact force by changing resistance under pressure. Load cells precisely measure forces and weights. Six-axis force-torque sensors detect forces and moments in all directions, providing complete contact force information. Touch sensing enables safe interaction, allows robots to detect successful grasps, and provides feedback during manipulation that visual sensing alone cannot provide.

Environmental sensors measure conditions like temperature, humidity, light level, sound, air quality, or chemical composition. These sensors enable robots to characterize their operating environment, detect relevant events, or collect scientific data. A temperature sensor might trigger cooling systems when motors overheat. Microphones detect voice commands or interesting sounds. Gas sensors identify chemical hazards. Environmental sensing extends robot awareness beyond purely geometric and visual perception.

Sensor fusion combines multiple sensors to create more complete and reliable perception than any single sensor provides. A mobile robot might fuse wheel encoders, IMU, and visual odometry to track its position more accurately than any single method could achieve alone. Redundant sensors measuring the same quantity improve reliability, while complementary sensors measuring different aspects provide comprehensive environmental awareness. The robot’s brain implements fusion algorithms that integrate diverse sensor streams into unified perceptual representations.

Sensor selection parallels actuator selection in requiring thoughtful tradeoffs. Accuracy determines measurement precision. Range specifies minimum and maximum detectable distances or values. Response time indicates how quickly sensors update. Field of view or directionality affects what spatial area sensors perceive. Cost, size, weight, and power consumption all constrain sensor choices. Matching sensors to the actual perceptual requirements of your robot’s tasks ensures effective sensing without unnecessary expense or complexity.

Sensor placement and mounting significantly affect performance. Distance sensors need unobstructed views in relevant directions. Cameras require stable mounting to minimize motion blur. IMUs should mount near the robot’s center to accurately represent overall motion. Considering these physical integration aspects during design prevents situations where theoretically excellent sensors fail to work well because they mount in poor locations or suffer mechanical interference.

The Brain: The Control and Decision System

The robot’s brain processes sensor information and commands actuators, serving as the central coordinator that transforms sensory input into meaningful action. This component typically consists of a programmable computer ranging from simple microcontrollers to powerful single-board computers or even full PCs, depending on computational requirements. The brain runs software that embodies all the logic determining how your robot behaves, making it the component that most directly reflects your design intentions and programming skills.

Microcontrollers represent the simplest and most common brain type for basic robots. These integrated circuits combine a processor, memory, and input/output interfaces in a single chip designed for embedded control applications. Popular platforms like Arduino use microcontrollers that run programs controlling motors, reading sensors, and implementing basic behaviors. Microcontrollers excel at real-time control tasks requiring quick, predictable responses to sensor inputs. They consume little power, cost relatively little, and provide exactly the capabilities simple robots need without unnecessary complexity.

The programming model for microcontrollers typically involves writing code that runs in an infinite loop, repeatedly reading sensors, making decisions, and commanding actuators. This straightforward control flow makes microcontroller programming accessible to beginners while remaining powerful enough for sophisticated applications. Languages like C or simplified versions like Arduino’s simplified C++ provide low-level control over hardware while maintaining reasonable programmer productivity.

Single-board computers like Raspberry Pi offer substantially more computing power than microcontrollers, running full operating systems like Linux and executing complex programs including computer vision, artificial intelligence, and sophisticated algorithms. These platforms suit robots requiring substantial computational capability for processing camera images, running neural networks, or performing complex planning. The tradeoff involves higher cost, greater power consumption, and more complex software environments compared to microcontrollers.

Many robots employ both microcontrollers and single-board computers in hybrid architectures. The microcontroller handles real-time sensor reading and motor control, tasks requiring quick, predictable responses. The more powerful computer processes vision, runs AI algorithms, or performs high-level planning. This division of labor plays to each processor type’s strengths, with the computer handling computationally intensive tasks while the microcontroller ensures real-time responsiveness.

Processing speed and computational capacity determine what algorithms and behaviors your robot can execute. Simple reactive behaviors where sensor readings directly map to motor commands require minimal processing. Complex tasks like simultaneous localization and mapping, real-time object recognition, or model-predictive control demand substantial computational resources. Understanding these requirements helps you select appropriate brain hardware that can execute your intended behaviors at the necessary rates.

Memory capacity affects what data your robot can store and process. RAM provides working memory for active computations, sensor buffering, and algorithm execution. Flash memory or SD cards store programs, maps, logged data, or trained neural network models. Insufficient memory limits algorithmic sophistication or forces compromises like reducing map resolution or limiting sensor history. Ensuring adequate memory for your robot’s needs prevents frustrating limitations discovered after hardware selection.

Input/output capabilities determine how many sensors and actuators the brain can control. Microcontrollers feature numerous digital and analog I/O pins connecting directly to sensors and actuators. Computers typically have fewer direct hardware interfaces, often requiring additional boards or USB adapters to connect many sensors. Counting required I/O connections and ensuring your chosen brain provides sufficient interfaces prevents last-minute discoveries that you cannot connect all your components.

Communication interfaces enable the brain to network with other systems or receive commands. WiFi and Bluetooth provide wireless connectivity for remote control, data transmission, or cloud services. USB allows connecting peripherals like cameras or additional sensors. Serial interfaces like UART, I2C, and SPI connect to sensors and motor drivers. Ensuring your robot brain includes necessary communication capabilities for your application prevents isolation or limits on connectivity.

Programming environments and available software libraries strongly influence productivity and capability. Well-documented platforms with extensive libraries for sensors, motors, and algorithms accelerate development. Obscure platforms might offer excellent hardware but lack software support, forcing you to write everything from scratch. Choosing platforms with active communities and rich software ecosystems provides resources and examples that speed learning and development.

Real-time performance requirements shape brain selection. Some applications tolerate occasional delays or variable processing times. Others, like balancing robots or high-speed manipulation, require guaranteed response times within strict deadlines. Microcontrollers and real-time operating systems provide the deterministic timing these applications demand, while general-purpose computers and operating systems prioritize throughput over timing guarantees. Understanding your timing requirements guides appropriate brain choices.

Integration: Connecting Anatomy into Functional Systems

Understanding actuators, sensors, and brains individually provides necessary foundation, but creating functional robots requires integrating these components into systems where they work together seamlessly. The connections between anatomical components, both physical and logical, determine whether your collection of parts becomes a functional robot or remains a non-functional assembly.

Physical connections involve wiring that routes power and signals between components. Actuators need power supplies providing adequate current and motor control signals specifying speed and direction. Sensors connect to the brain through analog or digital interfaces carrying measurement data. Power distribution must safely deliver appropriate voltages to different components, often requiring voltage regulators when components need different voltages. Clean, organized wiring prevents shorts, reduces electromagnetic interference, and simplifies troubleshooting when problems occur.

Logical connections involve software that reads sensors and controls actuators based on programmed behaviors. Your code implements the control loops that give the robot purposeful behavior. Reading sensor values, processing that information through control algorithms, and commanding actuators appropriately creates the sense-think-act cycle fundamental to robotics. The sophistication of these logical connections determines how intelligently your robot behaves.

Communication protocols standardize how components exchange information. Motors might receive commands via PWM signals, serial commands, or specialized protocols like CAN bus. Sensors might output analog voltages, digital signals, or data packets over I2C or SPI buses. Your brain must support these protocols and your code must implement proper communication sequences. Understanding and correctly implementing these protocols ensures reliable component interaction.

Timing and synchronization coordinate activities across subsystems. Sensors sample at specific rates. Control loops execute at defined frequencies. Motors respond to commands with particular dynamics. Ensuring these temporal aspects align properly prevents problems like motors receiving commands faster than they can respond or sensors being read slower than events occur. Well-designed systems carefully orchestrate timing across all components.

Power budgeting ensures your power system can support all actuators and electronics simultaneously. Motors draw substantial current, especially when starting or under load. Summing worst-case current draws for all components reveals total power requirements, informing battery and power supply selection. Inadequate power budgeting results in brownouts where voltage sags under load, causing erratic behavior or resets. Careful planning prevents these frustrating issues.

Error handling and fault tolerance acknowledge that sensors fail, actuators jam, and software bugs occur. Robust systems detect these problems and respond appropriately rather than catastrophically failing. Sensor readings outside plausible ranges might indicate failures. Motor current exceeding expected values might mean jams or collisions. Implementing monitoring and protective responses creates resilient systems that degrade gracefully rather than failing dangerously when components misbehave.

Modularity and abstraction organize complex systems into manageable pieces. Rather than writing monolithic code that does everything, creating separate modules for sensor reading, motion control, and behavior coordination makes systems comprehensible and maintainable. Abstraction layers hide implementation details, allowing you to think about high-level behaviors without constantly worrying about low-level hardware details. Good system architecture applying these principles scales far better than ad-hoc approaches as complexity grows.

Practical Anatomy: Recognizing Components in Real Robots

Developing ability to identify actuators, sensors, and brains in actual robots helps you learn from existing designs and understand how different applications employ these anatomical components. Looking at any robot, you can ask “What are its actuators? What sensors does it use? Where is its brain?” Answering these questions reveals the designer’s choices and helps you understand why the robot works as it does.

A wheeled mobile robot reveals its anatomy readily. The motors driving the wheels are obvious actuators, often visible or at least traceable through drive shafts or belts. Distance sensors pointing outward detect obstacles, while wheel encoders provide motion feedback. The microcontroller board, perhaps an Arduino, serves as the brain processing sensor data and controlling motors. Understanding this anatomy helps you see how the components work together to create autonomous navigation.

Robotic arms display different anatomical arrangements. Each joint contains an actuator, usually a servo motor or geared brushed motor. Encoders at joints provide position feedback. Force-torque sensors might mount at the wrist. The end effector, whether a gripper, vacuum tool, or specialized attachment, contains additional actuators for grasping or manipulation. A computer processes inverse kinematics and plans motions, sending commands to joint controllers. This distributed control architecture reflects the complexity of coordinating multiple actuated joints.

Consumer robots like robot vacuum cleaners conceal their anatomy inside enclosures, but you can infer components from behaviors. Motors drive wheels and operate vacuum and brush systems. Cliff sensors detect stairs. Bump sensors detect collisions. Distance sensors or cameras enable navigation. A microcontroller or small computer coordinates everything, implementing algorithms that clean rooms efficiently. The miniaturization and integration reflect mature product engineering but still employ the same anatomical components all robots require.

Industrial robots in manufacturing reveal professional-grade implementations. Heavy-duty motors with reduction gearboxes provide the power and precision for moving payloads. Absolute encoders at each joint provide precise position feedback. Vision systems might inspect parts or guide positioning. Powerful industrial controllers run sophisticated motion planning and safety monitoring algorithms. The scale and cost differ from hobbyist robots, but the anatomical framework remains the same.

Research robots often showcase cutting-edge components. Advanced sensors like 3D LIDAR or multi-spectral cameras provide rich perception. Custom actuators might employ novel mechanisms or materials. Powerful computers run experimental algorithms for machine learning, perception, or control. Understanding the anatomy helps you follow research papers and understand what capabilities new components or algorithms enable.

The Anatomical Perspective: A Framework for Understanding

This anatomical framework of actuators, sensors, and brains provides more than just vocabulary for discussing robots. It offers a systematic way of thinking about robot design, analysis, and troubleshooting. When planning a new robot, thinking anatomically helps you make appropriate component selections. When analyzing existing robots, it helps you understand design choices and tradeoffs. When debugging problems, it helps you systematically isolate whether issues originate in sensing, actuation, or control.

As you gain experience, you will develop intuition about what actuators, sensors, and brain capabilities different tasks require. Simple navigation needs basic distance sensors, modest motors, and a simple microcontroller. Computer vision applications demand cameras and substantial computing power. Precise manipulation requires encoders, force sensors, and sophisticated control algorithms. This intuition guides you toward appropriate designs without excessive trial and error.

The anatomical components also highlight where robotics draws from different engineering disciplines. Actuators involve mechanical and electrical engineering. Sensors span electrical engineering and physics. Brains require computer science and software engineering. Successful robotics integrates all these disciplines, explaining both why robotics is challenging and why it is fascinating. Each component type offers depth for specialization while the integration demands broad understanding.

Understanding robot anatomy through actuators, sensors, and brains transforms the overwhelming complexity of complete robots into comprehensible systems. You can examine any robot and identify these three component categories, understand what each contributes, and appreciate how they integrate into functional wholes. This framework applies universally across all robots regardless of size, application, or sophistication. Whether you are building your first simple robot or analyzing advanced research platforms, thinking anatomically helps you understand how these machines work and guides you toward effective design decisions in your own robotics projects.