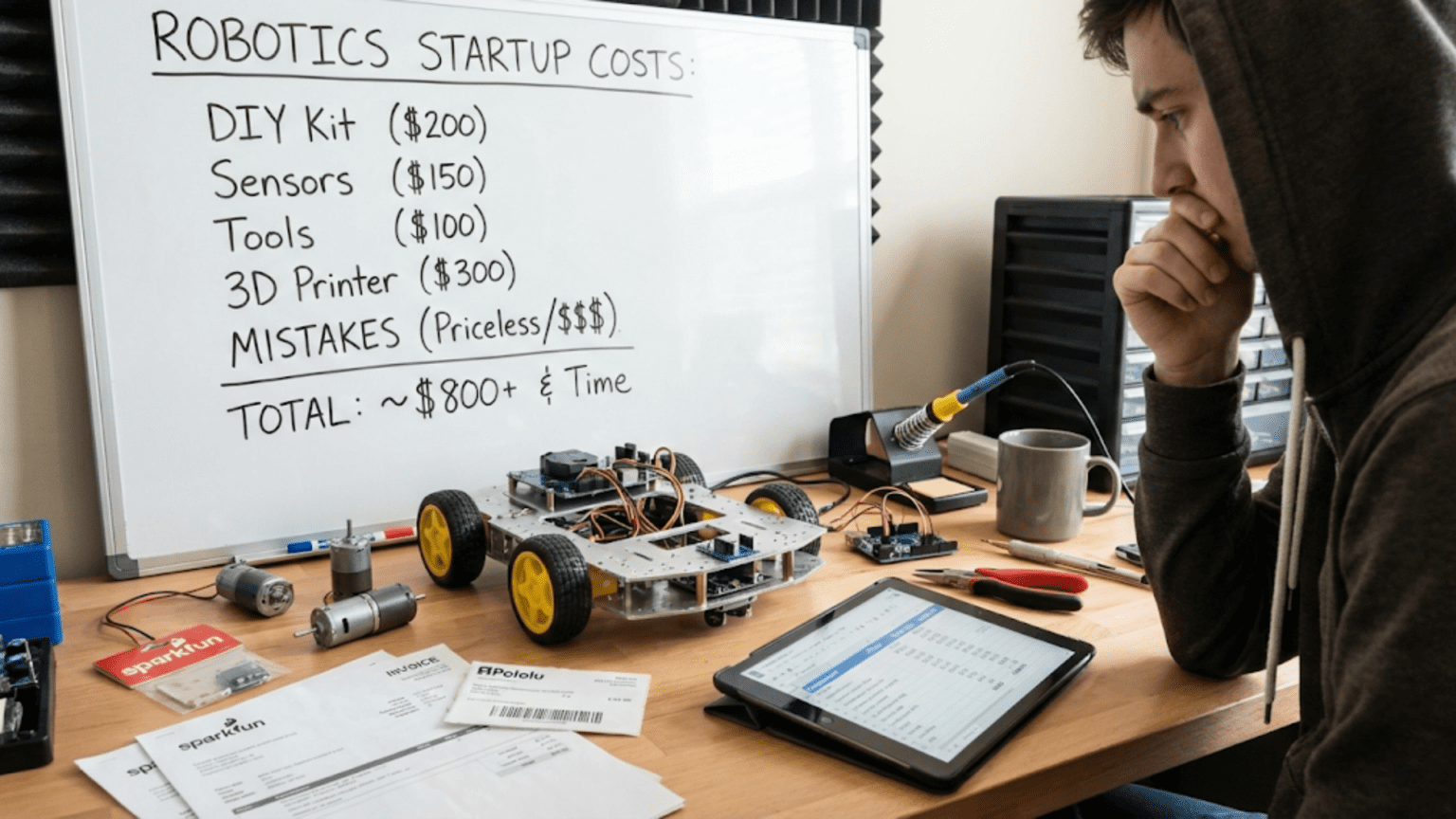

One of the first practical questions people ask when considering robotics is how much money they need to invest before building their first robot. The uncertainty about costs stops many potentially interested people from ever starting, worried that robotics requires expensive equipment, costly components, and substantial financial commitment. Meanwhile, others dive in enthusiastically only to discover unexpected expenses that strain their budgets. Understanding the realistic costs involved in starting robotics helps you plan appropriately, make informed purchasing decisions, and avoid both premature discouragement from overestimating costs and budget shocks from underestimating them.

The honest answer to “how much does robotics cost?” is that it varies enormously based on what you want to build, how quickly you want to progress, and what resources you already possess. You can meaningfully start learning robotics for under fifty dollars if you choose appropriate entry points and exercise patience. Conversely, you could easily spend thousands of dollars acquiring comprehensive tool sets, multiple platforms, and extensive component collections. Between these extremes lie numerous paths with different cost profiles, each offering valid entry into robotics.

This article breaks down robotics costs into categories, examines what different budget levels enable, identifies where you can economize versus where investment pays dividends, and helps you create a realistic budget matching your goals and financial situation. Rather than prescribing a single approach, this exploration reveals the financial landscape of robotics, empowering you to make conscious choices about what to purchase, what to defer, and how to maximize value from whatever budget you have available.

Starting Budget: Under One Hundred Dollars

Contrary to common perception, you can begin hands-on robotics with remarkably modest investment. While limited budgets constrain what you can build initially, they do not prevent meaningful learning or satisfying projects. Understanding what minimal investment enables helps you determine whether financial barriers are genuine obstacles or misconceptions.

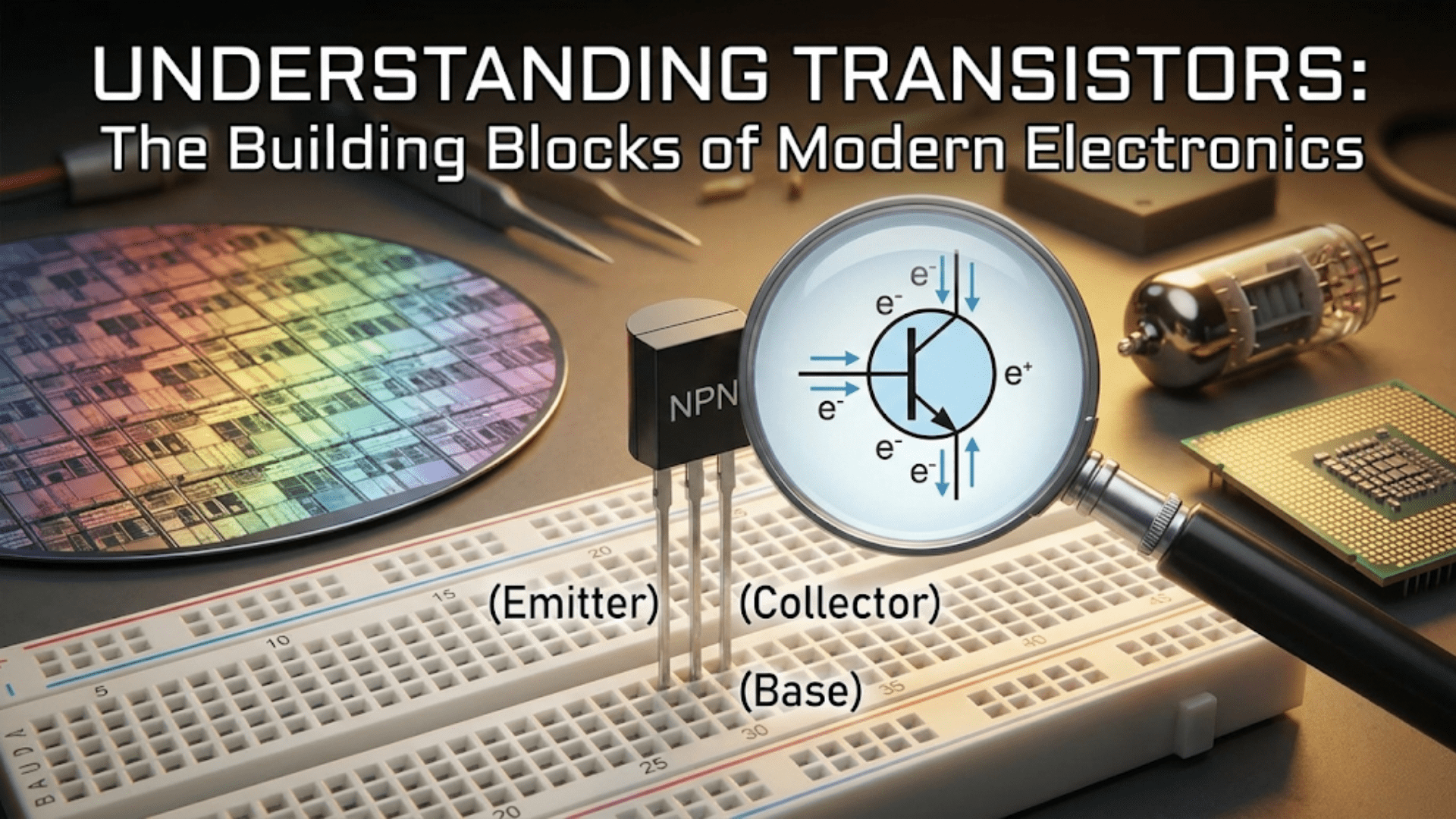

A basic Arduino starter kit costs between forty and seventy dollars and includes a microcontroller board, breadboard, jumper wires, resistors, LEDs, sensors, and often small motors or servos. These kits contain sufficient components to build dozens of introductory projects while learning fundamental concepts. The microcontroller can be reprogrammed countless times, making it reusable across many different projects. This single purchase provides months of learning opportunities for someone working through Arduino tutorials and experimenting with different circuits and programs.

Alternative low-cost platforms like ESP32 or basic Raspberry Pi Pico boards cost under twenty dollars yet offer substantial capabilities including built-in WiFi and Bluetooth on ESP32 boards. These inexpensive microcontrollers access the same learning resources, tutorials, and community support as more expensive options. Starting with less costly boards lets you experiment without worry about damaging expensive equipment, which ironically might accelerate learning by reducing anxiety about mistakes.

Used or surplus components dramatically reduce costs for budget-conscious beginners. Electronics surplus stores, online marketplaces, and robotics forums often offer used servos, motors, sensors, and other components at fractions of retail prices. While cosmetically worn, functional surplus components work identically to pristine new parts. Many experienced roboticists gleefully hunt bargains, viewing surplus hunting as part of the hobby rather than unfortunate necessity. This scavenging mindset stretches limited budgets remarkably far.

Household materials supplement purchased electronics affordably. Cardboard, plastic bottles, craft sticks, and other recyclables provide structural materials for robot chassis and mechanical components. While less durable than purpose-made materials, household scraps cost nothing and prove adequate for learning projects where perfect reliability matters less than experimenting with concepts. Many impressive educational robots use intentionally inexpensive materials to demonstrate that creativity matters more than expensive components.

Free software eliminates major cost categories that plague other technical hobbies. Arduino IDE, Python, and numerous robotics libraries cost nothing, providing professional-grade development environments without subscription fees or purchase prices. While some commercial robotics software requires expensive licenses, free alternatives suit beginners perfectly well. This zero software cost means every dollar you spend goes toward physical components rather than licensing.

Battery costs require attention as they represent ongoing expenses. Rechargeable AA or AAA batteries with a charger cost twenty to forty dollars initially but pay for themselves quickly compared to disposable batteries. Many robotics projects drain batteries rapidly, making rechargeables economically essential. Planning for rechargeable batteries in your initial budget prevents the frustrating realization that your new robot eats expensive disposable batteries.

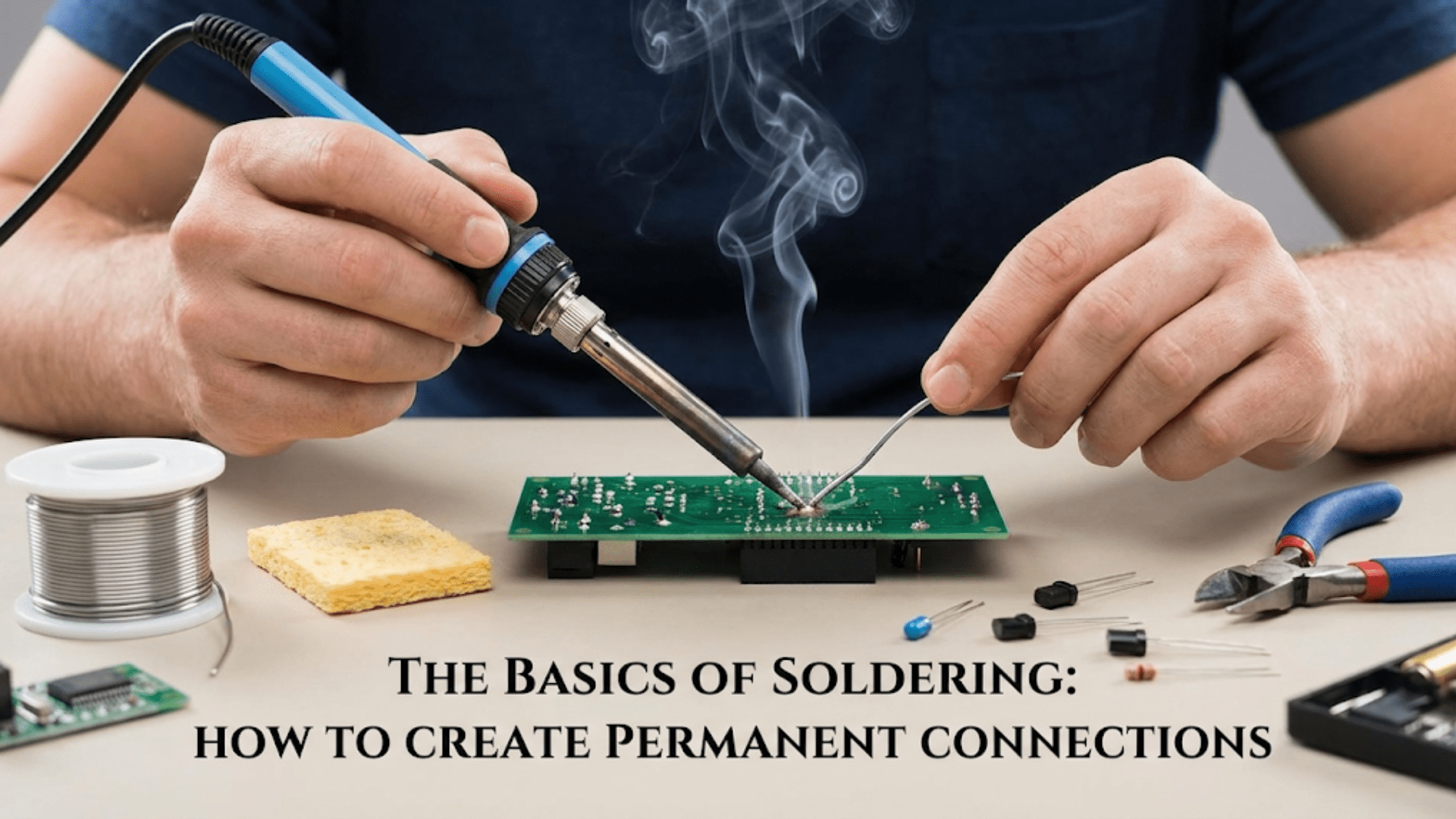

Tools represent another cost category, though starting tool requirements remain modest. A basic multimeter for measuring voltages and testing connections costs ten to twenty dollars. A soldering iron kit for permanent connections runs twenty to forty dollars. Small screwdrivers, pliers, and wire strippers add another fifteen to thirty dollars. These tools last for years and serve countless projects, making them worthy investments even in tight budgets. Many beginners already own some basic tools, reducing required spending.

At the sub-hundred-dollar level, you will build small, relatively simple robots using provided components and tutorials. Your robots might be wheeled platforms that avoid obstacles, line followers, or simple arms controlled by servos. These projects teach fundamental concepts about sensors, motors, programming, and control that apply directly to more sophisticated robots. The technical knowledge and practical skills you gain have value independent of how much money you spent acquiring them.

Intermediate Budget: One Hundred to Three Hundred Dollars

Moving beyond minimal investment into the hundred to three hundred dollar range significantly expands what you can build and how quickly you can progress. This budget tier enables purchasing complete robot kits, acquiring a more comprehensive component collection, and adding more capable development platforms while remaining accessible to many hobbyists.

Complete robot kits in this price range provide integrated platforms designed for specific applications. A quality wheeled robot kit with chassis, motors, motor drivers, sensors, and microcontroller might cost between one hundred and two hundred dollars. These kits eliminate the need to source individual components, ensure compatibility, and often include detailed instructions and community support. While more expensive than sourcing parts individually, kits save time and reduce frustration from incompatible components or unclear wiring.

More capable microcontroller boards and single-board computers become accessible at this budget level. A Raspberry Pi with necessary accessories costs around seventy-five dollars, providing Linux computing power for computer vision, web interfaces, and sophisticated programming. Arduino Mega boards with many more input/output pins than basic Arduinos cost around forty dollars, enabling robots with numerous sensors and actuators. These upgraded platforms handle more complex projects while remaining programmatically similar to cheaper boards you might start with.

Improved sensors expand perceptual capabilities significantly. LIDAR sensors that precisely map environments cost between one hundred and two hundred dollars at the entry level. Better cameras with higher resolution or specialized features like depth sensing range from thirty to one hundred dollars. Force-torque sensors, IMUs with better specifications, and more reliable distance sensors all become affordable. These upgraded sensors enable more sophisticated behaviors and more robust operation in challenging conditions.

More powerful motors and actuators allow building larger, more capable robots. Geared DC motors with encoders providing speed and position feedback cost twenty to fifty dollars each. Standard hobby servos cost ten to thirty dollars depending on torque and precision. These actuators provide the power and control for robots that manipulate meaningful loads or traverse challenging terrain rather than just demonstrating concepts with minimal mass and force.

A growing component collection enables spontaneous experimentation. Stocking various resistors, capacitors, LEDs, switches, sensors, and connectors means you can try ideas immediately rather than waiting for specific part orders. A well-organized collection of common components might cost one hundred to two hundred dollars but provides freedom to explore without planning every component purchase. This inventory represents investment in enabling creativity rather than any specific project.

Better tools improve work quality and efficiency. A temperature-controlled soldering station provides more consistent results than basic irons and costs fifty to one hundred dollars. A decent power supply for bench testing eliminates battery concerns during development and costs forty to eighty dollars. Improved wire strippers, flush cutters, and precision screwdriver sets make assembly cleaner and faster. While these tools seem like luxuries, they save time and reduce frustration significantly.

Books, courses, or premium online resources might enter your budget at this level. While vast free resources exist, quality books or structured courses cost thirty to one hundred dollars and provide organized learning paths that accelerate progress. For some learners, this educational investment yields better returns than equivalent spending on components. Balancing education spending against hardware spending depends on your learning style and access to free resources.

At this intermediate budget level, you can build substantial robots with real capabilities. Mobile platforms that autonomously navigate mapped environments, manipulator arms with multiple degrees of freedom and position feedback, or robots integrating computer vision for object recognition all become feasible. Your projects begin resembling scaled-down versions of professional systems rather than purely educational demonstrations.

Advanced Amateur Budget: Three Hundred to One Thousand Dollars

Investing three hundred to one thousand dollars in robotics positions you to tackle ambitious projects approaching professional capability while remaining within serious hobby budgets. This spending level enables multiple robot platforms, comprehensive tool collections, and premium components that reduce frustration and improve results.

Multiple development platforms let you work on several projects simultaneously and experiment with different approaches. Owning both Arduino-compatible boards for real-time control and Raspberry Pi computers for complex processing lets you combine their strengths in hybrid architectures. Having extra microcontrollers means you can dedicate one to a project permanently rather than constantly swapping the same board between experiments. Platform diversity costs more initially but accelerates learning by enabling comparisons and parallel development.

Professional-grade components improve reliability and performance noticeably. Industrial-quality sensors provide more accurate readings with better noise immunity. Metal-geared servos withstand higher loads without stripping plastic gears. Precision linear actuators enable controlled motion that hobby-grade alternatives struggle to achieve. While considerably more expensive than basic components, professional-grade parts reduce time wasted troubleshooting unreliable components and enable applications requiring consistent, dependable operation.

Comprehensive tool collections enable efficient, high-quality work. A good oscilloscope for viewing and debugging electronic signals costs two hundred to five hundred dollars. Logic analyzers for examining digital communications run fifty to two hundred dollars. Quality mechanical tools including taps, dies, files, and precision measurement tools add another one hundred to three hundred dollars. These professional tools might seem unnecessary initially, but they solve problems that simple tools cannot address and dramatically accelerate troubleshooting complex issues.

Fabrication equipment transforms robot construction possibilities. A basic 3D printer costs two hundred to four hundred dollars and enables custom mechanical parts impossible to obtain otherwise. A decent rotary tool with accessories costs one hundred to two hundred dollars and handles cutting, grinding, and polishing. Better drill presses, band saws, or laser cutters fall into this budget range in basic forms. Fabrication capabilities eliminate dependence on pre-made parts and enable truly custom robot designs.

Specialty robot platforms in this price range include hexapod kits, robot arms with five or six degrees of freedom, or research-oriented platforms providing experimental testbeds. These sophisticated kits cost four hundred to eight hundred dollars but provide integrated systems with extensive documentation and community support. They enable exploring advanced topics like gait generation, inverse kinematics, or multi-robot coordination using proven platforms rather than struggling with custom hardware challenges while trying to learn advanced concepts.

Software tools mostly remain free even at this budget level, though some professionals might purchase licenses for CAD software, circuit design tools, or simulation packages. However, free alternatives like FreeCAD, KiCAD, and Gazebo provide substantial capabilities without cost. Most roboticists continue using free software regardless of budget, reserving spending for physical components and tools.

Training and education investments become more significant at this level. Attending robotics workshops, conferences, or intensive courses costs one hundred to several hundred dollars but provides concentrated learning and networking opportunities. Purchasing comprehensive reference books, online course subscriptions, or specialized training materials represents worthwhile investment in knowledge that multiplies the value of your component and tool investments.

This advanced amateur budget enables robots with genuine utility and impressive capabilities. You could build autonomous lawnmowers, telepresence robots with sophisticated computer vision, multi-robot systems demonstrating swarm behaviors, or manipulation systems capable of assembly tasks. Projects at this level represent serious engineering accomplishments that demonstrate substantial robotics competence.

Professional and Research Budgets: Beyond One Thousand Dollars

Professional robotics development and serious research typically involve budgets exceeding several thousand dollars, reflecting both higher capability requirements and professional-grade reliability expectations. Understanding these costs provides perspective even if you work at hobbyist levels, showing where the serious money goes in professional contexts.

Industrial robot arms from established manufacturers like Universal Robots, ABB, or Fanuc cost twenty thousand to one hundred thousand dollars or more depending on specifications. These professional manipulators provide precision, reliability, safety features, and support that justify their prices for industrial applications. Hobbyist-grade robot arms might cost one thousand to five thousand dollars and offer impressive capabilities while lacking industrial certification and support infrastructure.

Professional mobile robot platforms including autonomous vehicles, advanced drones, or research robots cost five thousand to fifty thousand dollars. These platforms integrate sophisticated sensors, powerful computers, custom mechanical designs, and extensive software. They enable research or commercial applications impossible with cheaper platforms but represent serious investments accessible primarily to institutions or companies rather than individuals.

Custom fabrication equipment in professional settings includes CNC mills, laser cutters, welding equipment, and metrology instruments costing thousands to tens of thousands of dollars. While individual hobbyists rarely justify such equipment, maker spaces and shared workshops make these capabilities accessible through memberships costing tens to hundreds of dollars monthly. Shared access democratizes advanced fabrication while avoiding individual ownership costs.

Computing infrastructure for robotics research can become surprisingly expensive. GPU workstations for machine learning cost three thousand to ten thousand dollars. Multiple development machines, network infrastructure, and servers add thousands more. Cloud computing partially offsets these costs but introduces ongoing service fees. Professional robotics development increasingly requires substantial computing investment alongside mechanical and electronic components.

Sensor suites on professional robots often exceed complete hobby robot budgets. A single high-end LIDAR sensor costs five thousand to seventy-five thousand dollars. Multi-spectral cameras, precision IMUs, RTK GPS systems, and specialized sensors each cost hundreds to thousands of dollars. Professional autonomous vehicles might carry sensor packages worth one hundred thousand dollars or more, enabling perception capabilities beyond hobbyist reach.

The reason for mentioning these professional costs is not to discourage hobby robotics but to provide context. Professional robotics justifies high spending through commercial applications, research funding, or institutional budgets that amateur work cannot access. However, hobbyists benefit from technology trickling down—today’s two-hundred-dollar LIDAR sensor would have cost ten thousand dollars a decade ago. Understanding the professional landscape helps appreciate available affordable options while recognizing inherent limitations compared to systems costing orders of magnitude more.

Where to Save Money Without Sacrificing Learning

Strategic economizing lets you maximize learning per dollar spent without compromising educational value. Some costs provide excellent returns while others represent optional luxuries. Understanding the difference helps you allocate limited budgets optimally.

Starting with simpler projects before ambitious ones saves money by teaching lessons cheaply that would cost more to learn on expensive hardware. A twenty-dollar line-following robot teaches sensor reading, motor control, and programming concepts identically to a two-hundred-dollar advanced platform. Learn core skills on basic hardware, then apply that knowledge to more sophisticated systems. This progression builds competence while matching spending to skill level.

Borrowing, sharing, or accessing tools through maker spaces eliminates ownership costs for infrequently needed equipment. Paying twenty dollars to use a laser cutter at a maker space beats purchasing a five-thousand-dollar cutter for occasional use. Tool libraries, community workshops, and university maker spaces provide access to capabilities beyond individual budgets. Membership fees provide remarkable value when they unlock extensive shared resources.

Open-source hardware and software eliminate licensing costs while providing full functionality. Arduino-compatible clones cost half or less than official boards while working identically for learning purposes. Free CAD and design tools handle most needs without expensive commercial licenses. Supporting open-source projects through small donations or community participation provides ethical way to benefit from free resources while contributing to their sustainability.

Used components and equipment from online marketplaces, garage sales, or electronics surplus stores stretch budgets dramatically. Experienced roboticists treat surplus hunting as entertainment, finding functional components at fractions of retail cost. While used items require more careful inspection and present some reliability risk, they enable experimentation that would be financially prohibitive using only new components.

Modular, reusable designs let you repurpose components across multiple projects. Rather than building dedicated single-purpose robots, design systems where you can swap different sensor arrays, exchange controllers, or reconfigure mechanical platforms. This modularity means your components collection enables numerous different robots serially without purchasing duplicates of expensive parts.

Prioritizing versatile components over specialized ones provides more flexibility per dollar. A good motor driver that handles various motor types and voltages serves more projects than one specialized for specific motors. Sensors with broad measurement ranges work across more applications than narrow-range specialists. This versatility strategy builds collections that support diverse projects from limited budgets.

Where Investment Pays Dividends

While economizing makes sense for many purchases, some strategic investments provide disproportionate returns through improved results, reduced frustration, or accelerated learning. Understanding where to invest versus where to economize optimizes your robotics spending.

Quality tools last for years and make work dramatically more efficient and enjoyable. A good soldering station costs three times a basic iron but produces cleaner joints faster with less frustration. Precision screwdrivers reach fasteners that cheap sets cannot access. Sharp, quality cutting tools make clean cuts easily while dull cheap tools require force and produce rough results. Tools represent long-term investments serving countless projects—buying quality pays for itself through better results and reduced replacement costs.

Reliable power supplies and battery management prevent countless problems. Poor voltage regulation causes erratic behavior that wastes hours troubleshooting. Low-quality chargers damage batteries and create fire risks. Investing in proper power infrastructure seems boring but prevents enormous time waste and safety hazards. Good power supplies cost more initially but eliminate entire categories of frustrating problems.

Educational resources including quality books, courses, or workshops accelerate learning beyond what equivalent spending on components achieves. Struggling alone with poor documentation might eventually produce learning but wastes time that structured education bypasses. The right book or course can save dozens of hours of frustration while teaching proper techniques from the start. Educational investment pays returns through faster progress and better fundamental understanding.

One really good development platform often serves better than multiple mediocre ones. A capable microcontroller or single-board computer with good documentation, extensive community support, and sufficient power handles diverse projects. Accumulating many different basic boards fragments your attention and requires learning multiple platforms. Focus spending on proven platforms with strong ecosystems rather than chasing the latest or cheapest options.

Versatile sensors that work reliably across varied conditions cost more but enable more projects successfully. Cheap sensors work under ideal conditions but fail in real-world environments with lighting variations, temperature changes, or electrical noise. Better sensors expand what you can accomplish with robots and reduce time wasted compensating for sensor limitations. Sensor investment frequently determines project success, making it worth spending appropriately.

Hidden and Ongoing Costs

Beyond obvious component and tool purchases, robotics involves less apparent costs that affect total spending. Anticipating these helps you budget realistically and avoid unpleasant surprises.

Shipping costs for components ordered online can equal or exceed component costs for small orders. A five-dollar sensor with eight-dollar shipping effectively costs thirteen dollars. Consolidating orders to amortize shipping over multiple items reduces per-item costs significantly. Balancing desire for immediate parts against cost efficiency requires patience but saves money over time.

Replacement parts for damaged components add costs over time. Motors burn out from overcurrent. Sensors break when robots collide with obstacles. Microcontrollers fail from wiring mistakes. Budget for occasional replacement parts as learning costs—mistakes happen, components fail, and replacement enables continued work. Maintaining a small emergency parts inventory prevents total work stoppage when components fail.

Electricity costs for charging batteries, running power supplies, and operating computers remain small but non-zero. While unlikely to significantly impact budgets, awareness of operational costs provides complete spending picture. 3D printers and other fabrication equipment particularly consume notable electricity over extended operations.

Consumables including solder, wire, adhesives, fasteners, and other materials need periodic replenishment. A spool of solder might last years but eventually runs out. Wire stocks deplete. Bolts and fasteners get used. Budgeting small amounts monthly for consumables prevents running out at inconvenient times.

Workspace costs depend on your situation. If you must rent dedicated workspace, monthly costs become significant. Home workshops might require shelving, workbenches, lighting, or climate control investments. While many people accommodate robotics in existing spaces without additional cost, some situations require spending on appropriate work environments.

Tool maintenance and calibration costs arise for professional-grade equipment. Oscilloscopes need occasional calibration. 3D printers require replacement nozzles and maintenance parts. Power tools need sharpening or replacement consumables. While often small individually, maintenance costs accumulate over time for extensive tool collections.

Building a Realistic Robotics Budget

Creating a practical robotics budget matching your goals and constraints enables pursuing the hobby sustainably without overextending financially or limiting progress unnecessarily.

Start by defining clear objectives. What do you want to build? What do you want to learn? Different goals suggest different spending priorities. Someone focused on learning programming might emphasize computing platforms and sensors over mechanical components. Someone interested in manipulation might prioritize motors, actuators, and mechanical hardware. Clarifying objectives prevents scattering spending across too many areas without achieving competence in any.

Research specific project requirements before purchasing to ensure you buy what you actually need. Jumping into buying without clear plans often results in acquiring components that do not work together or miss essential items. Studying tutorials and build guides for projects similar to your goals reveals realistic parts lists and helps you anticipate actual requirements.

Start smaller than your budget allows, leaving financial headroom for unexpected needs and mistakes. If you can afford three hundred dollars of robotics spending, plan initial purchases around two hundred dollars. The remaining budget buffer handles parts you forgot, components that fail, or opportunities for upgrades that emerge during development. This conservative approach prevents budget exhaustion before project completion.

Prioritize foundational purchases that serve multiple projects over specialized items useful only once. That first microcontroller, basic sensor set, simple motors, and essential tools support dozens of projects. Specialized components like specific vision sensors or custom mechanical assemblies only help particular projects. Build broad capabilities first, then add specialized items as specific projects require them.

Spread spending over time rather than front-loading massive purchases. Robotics rewards gradual accumulation of components and skills rather than demanding complete capability immediately. Buying a bit each month or project sustains the hobby long-term and provides time to learn what you actually need versus what seemed interesting initially but goes unused.

Track spending to understand where money goes and whether purchases provided value. Simple spreadsheets recording component costs, tool purchases, and project expenses reveal spending patterns. This awareness helps you refine purchasing decisions, identifying where you overspent on unused items or underspent causing project delays.

The realistic cost of starting robotics ranges from modest to substantial depending on your approach, goals, and constraints. Understanding this range, knowing where costs arise, and making informed decisions about what to purchase, what to defer, and where to invest versus economize lets you pursue robotics within your financial means while maximizing learning and accomplishment per dollar spent. The field welcomes participants regardless of budget through its remarkable range of accessible entry points and scaling opportunities as your capabilities and resources grow together.