Mathematics anxiety stops countless interested people from pursuing robotics, worried that complex equations and abstract theory will overwhelm them before they can build their first robot. The question “how much math do I need to know?” haunts beginners researching robotics, and vague answers ranging from “not much” to “you need calculus and linear algebra” create confusion rather than clarity. This uncertainty about mathematical prerequisites prevents many capable people from ever starting their robotics journey, convinced they must complete years of mathematics courses before touching actual robots.

The reality of mathematics in robotics proves more nuanced and encouraging than these extreme perspectives suggest. You absolutely can begin building functional robots with minimal mathematics—basic arithmetic and simple algebra suffice for many beginner projects. However, as your robotics ambitions grow, specific mathematical concepts unlock capabilities that remain inaccessible without them. The key insight is that you learn mathematics incrementally as projects demand it rather than frontloading years of abstract study before starting practical work. This just-in-time learning approach teaches mathematics in context where its value becomes immediately apparent.

This article clarifies what mathematics robotics actually requires at different levels, explains why particular mathematical concepts matter for specific robotics applications, and provides practical guidance for learning mathematics you need when you need it. Rather than prescribing comprehensive mathematics education before robotics work begins, this exploration reveals how mathematics and robotics learning can proceed together, each reinforcing the other. You will discover that mathematical requirements grow gradually with project complexity, that much mathematics becomes intuitive through hands-on experience, and that the mathematics you need for robotics feels different from abstract classroom mathematics because it solves concrete problems you actually care about.

Starting Simple: The Mathematics of First Robots

Your first robots require remarkably little formal mathematics. Understanding what basic mathematics enables helps you recognize you likely already possess necessary knowledge to begin, eliminating mathematics anxiety as barrier to starting.

Basic arithmetic—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—appears everywhere in simple robotics. Calculating how long to run motors at certain speeds to travel desired distances uses multiplication. Determining battery life from capacity and current draw uses division. Adjusting sensor thresholds involves comparing numbers. These arithmetic operations require only elementary school mathematics that you perform without conscious thought. If you can calculate change when buying groceries or measure ingredients for recipes, you have sufficient arithmetic for beginner robotics.

Simple algebra including variables and basic equations helps you understand relationships between quantities. If your robot’s speed equals motor power multiplied by some constant factor, that relationship is algebraic even if you never write it as equation. When you adjust motor power to achieve desired speed, you perform algebraic reasoning. Much robotics algebra remains implicit—you manipulate quantities based on their relationships without formal equation manipulation. The algebra you need initially feels more like practical problem-solving than classroom mathematics.

Ratios and proportions govern many robotics relationships. Gear ratios determine how motor speed and torque transform. Voltage dividers use resistor ratios to scale voltages. Proportional control uses input-output ratios to determine responses. Understanding that doubling input doubles output in proportional relationships, or that ten-to-one gear reduction multiplies torque by ten while dividing speed by ten, constitutes the ratio reasoning you need. This concept-level understanding suffices initially without formal ratio calculations.

Percentages appear when working with sensors, motors, and batteries. Sensor readings might scale from zero to one hundred percent of range. Motor speeds express as percentages of maximum. Battery charge states indicate as percentages of full capacity. Converting between percentages and absolute values uses division and multiplication you already know. Percentage concepts from everyday life transfer directly to robotics without additional learning.

Unit conversions occasionally arise when sensors or components use different measurement systems. Converting between centimeters and inches, grams and ounces, or degrees and radians uses multiplication by conversion factors. Online calculators handle most conversions, but understanding that conversion involves consistent scaling helps you verify results make sense. Unit awareness—recognizing when values need conversion and that results should have appropriate units—matters more than memorizing conversion factors.

This foundational mathematics that enables beginner robotics likely exists in your knowledge already. You learned these concepts through years of practical application in daily life. Recognizing that robotics uses familiar mathematics differently than classroom contexts dissolves much mathematics anxiety. The mathematics you need initially is mathematics you already use regularly, just applied to motors and sensors rather than shopping and cooking.

Geometry and Trigonometry: Understanding Space and Motion

As robots move through physical space and manipulate objects, geometric and trigonometric concepts become increasingly relevant. These mathematical tools help you understand robot positions, orientations, and motions in two and three dimensions.

Coordinate systems provide frameworks for describing positions. The Cartesian grid with X and Y axes that you learned in school describes robot positions in two dimensions. Understanding that position (5, 3) means five units right and three units up from origin, and that negative values indicate opposite directions, enables position tracking and navigation. Three-dimensional coordinates adding a Z axis extend to flying robots or manipulator arms reaching through space. This coordinate understanding requires only remembering conventions from school mathematics that you might have forgotten.

Distance calculations between points use the Pythagorean theorem relating right triangle sides. If your robot sits at position (0, 0) and target sits at (3, 4), the distance equals the square root of three-squared plus four-squared, which is five units. This classic geometry concept appears constantly in robotics—calculating distances to navigate, determining whether objects fall within reach, or measuring how far robots have traveled. The formula might require refreshing from geometry class, but the concept that distance relates to horizontal and vertical separations remains intuitive.

Angles and direction become crucial when robots need to orient toward targets or turn precise amounts. Understanding that angles measure rotation from reference direction, that full circle contains 360 degrees (or 2π radians), and that angles add when rotations combine enables directional control. When your robot turns 45 degrees then another 30 degrees, it has rotated 75 degrees total. This angle arithmetic supports navigation and orientation control.

Sine, cosine, and tangent functions relate angles to triangle sides, enabling calculations that seem mysterious until you understand their purpose. If your robot needs to move forward three meters then turn to face a target one meter to the side, trigonometry calculates the required angle. The tangent of angle equals opposite side divided by adjacent side, so arctan(1/3) gives the angle. While this might sound abstract, robotics provides concrete context—you see the triangle formed by robot path and target location, making trigonometric relationships intuitive rather than mystical.

Vector concepts represent quantities with both magnitude and direction. Robot velocity specifies both how fast and which direction it moves. Force applied to an object has both strength and direction. Adding vectors means combining their effects, which requires considering directions not just magnitudes. While formal vector mathematics involves sophisticated operations, basic vector intuition—that moving east three meters then north four meters results in position five meters northeast—suffices for many applications. This geometric understanding develops naturally through physical experience even without formal vector mathematics.

Rotation and transformation concepts explain how positions and orientations change. When your robot rotates, points on the robot move to new positions determined by rotation angle. Trigonometric functions calculate these new positions mathematically. Understanding that rotation preserves distances while changing directions provides geometric intuition supporting mathematical calculations. Many roboticists develop strong geometric intuition from building and observing robots, then learn formal mathematics codifying what they already understand intuitively.

Linear Algebra: Power Tools for Complex Robots

As robots become more sophisticated with multiple joints, coordinate transformations, and advanced algorithms, linear algebra emerges as powerful mathematical framework. This might sound intimidating, but understanding what linear algebra does and learning it gradually makes it accessible.

Matrices organize related numbers into rectangular arrays enabling compact representation and manipulation. A three-by-three matrix might represent rotation in three dimensions. Rather than tracking nine separate numbers and their interrelationships, matrices let you think about the rotation transformation as single entity. Initially, matrices seem like notation convenience. With experience, you recognize them as fundamental objects representing transformations, relationships, and systems of equations efficiently.

Matrix multiplication combines transformations. If one matrix represents rotation and another represents translation (moving without rotating), multiplying them creates single matrix representing both operations in sequence. This composition property makes matrices powerful for describing complex motions resulting from multiple simple transformations. While matrix multiplication follows specific rules different from regular multiplication, the concept that multiplying matrices combines their effects provides working understanding for many applications.

Coordinate transformations between reference frames become essential for manipulator arms with multiple joints. Your robot arm’s base has coordinate system describing positions relative to base. The gripper has its own coordinate system describing positions relative to gripper. Transforming positions between these coordinate systems requires matrix operations that linear algebra provides. This mathematical machinery lets you specify that the gripper should reach particular position in base coordinates, then calculate necessary joint angles to achieve it.

Vectors in linear algebra context represent arrays of numbers that matrices transform. While earlier we considered vectors as geometric arrows, linear algebra generalizes vectors to any array of related values. Sensor readings from multiple sensors can form vector. Joint angles in robot arm form vector. This abstraction enables applying powerful linear algebra tools to diverse robotics problems beyond purely geometric applications.

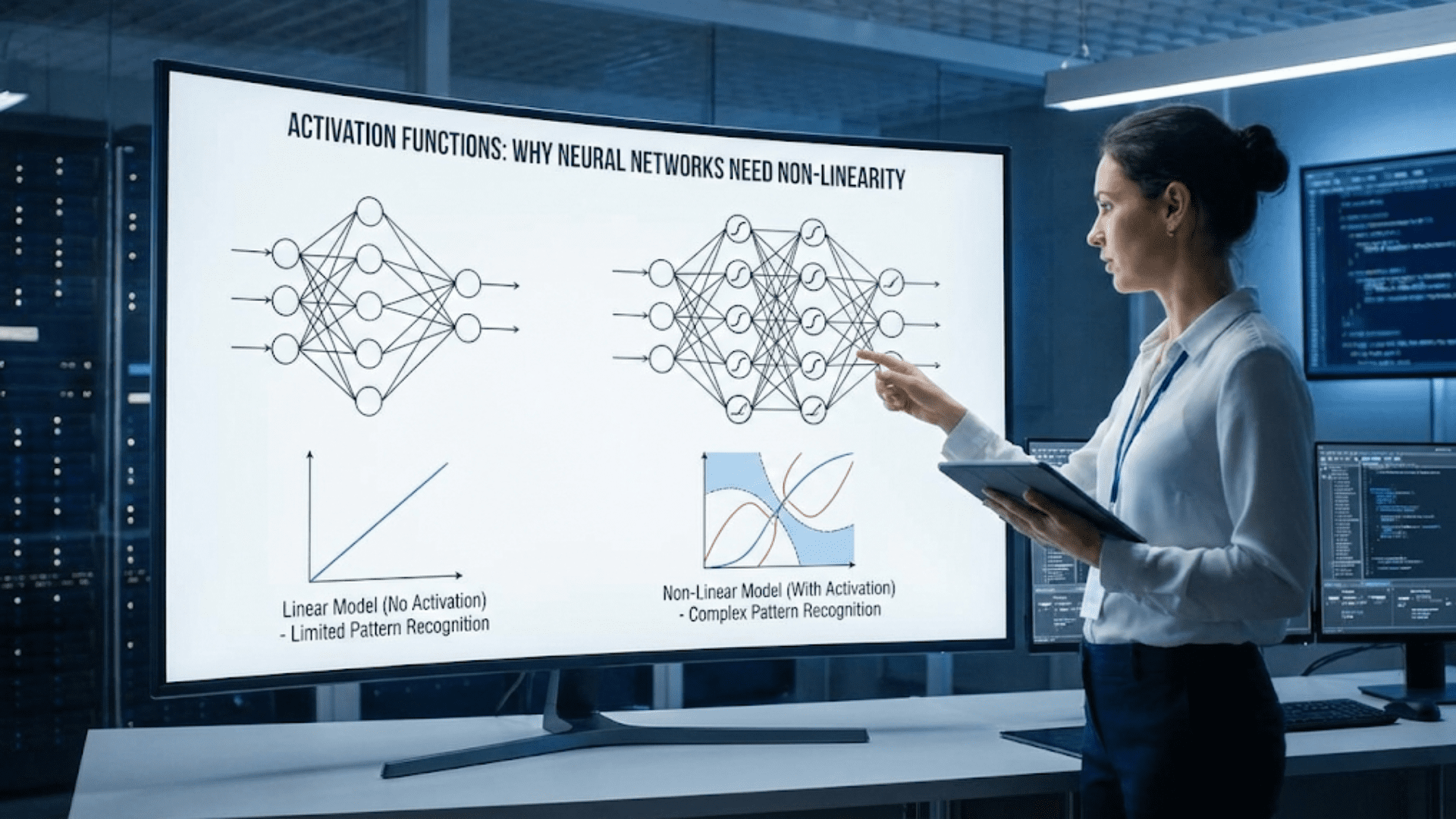

Systems of equations arise when multiple constraints must simultaneously hold. Inverse kinematics for robot arms—calculating joint angles achieving desired end position—creates systems of equations. Multiple sensors measuring same phenomenon create systems relating sensor readings to actual values. Linear algebra provides systematic methods solving such systems rather than guessing and checking. Understanding that these systematic solution methods exist, even before mastering them, helps you recognize when mathematical tools can replace trial and error.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors, while sounding esoteric, describe important system properties. In control systems, eigenvalues indicate stability—whether control loops converge to desired states or oscillate uncontrollably. While you need not calculate eigenvalues manually, understanding that they characterize system behavior helps you interpret analysis tools and debug control problems. Many advanced concepts become tools you use through software rather than calculating by hand.

Calculus: Understanding Change and Optimization

Calculus deals with rates of change and accumulation, concepts central to robot motion and control. While intimidating by reputation, the calculus you need for most robotics involves understanding concepts more than performing complex calculations.

Derivatives represent instantaneous rates of change. Velocity is derivative of position—how quickly position changes over time. Acceleration is derivative of velocity—how quickly velocity changes. Understanding these relationships helps you design motion profiles for robots. If you want smooth acceleration reaching target velocity, you need velocity changing gradually (bounded derivative) rather than instantaneously. This derivative thinking appears throughout robotics even when you never explicitly compute derivatives.

Integrals represent accumulation over time. If you know robot velocity, integrating velocity over time gives distance traveled. If you measure motor current, integrating current gives electric charge transferred. These accumulation concepts appear when tracking robot states from sensor measurements or calculating energy consumption from power draw over time. While numerical integration through software often replaces analytical integration, understanding that integration accumulates instantaneous measurements over intervals helps you recognize when this operation solves problems.

Differential equations describe how quantities change based on their current values. A simple example: velocity changes proportionally to applied force. This relationship forms differential equation governing motion. Control theory relies heavily on differential equations describing system dynamics. You rarely solve differential equations analytically in practical robotics, but recognizing that dynamic systems follow differential equations helps you understand simulation results and control algorithm behavior.

Optimization using calculus finds maximum or minimum values of functions. What motor speeds minimize power consumption while achieving desired travel time? What path minimizes distance while avoiding obstacles? What control gains minimize tracking error? Calculus-based optimization systematically finds these optimal values. Software packages implement optimization algorithms, but understanding that calculus provides mathematical foundation helps you use these tools effectively and interpret results correctly.

Taylor series and linearization approximate nonlinear relationships with simpler linear approximations near operating points. Many robot components behave nonlinearly—sensor response curves, motor torque-speed relationships, and friction forces all exhibit nonlinear characteristics. Linearizing around typical operating conditions enables applying linear control theory to these nonlinear systems. While formal Taylor series mathematics seems abstract, the concept that curved relationships approximate as straight lines over small ranges provides practical insight.

The encouraging reality about calculus in robotics is that much calculus happens inside software libraries and simulation tools. You invoke integration and differentiation through function calls without hand calculations. However, understanding conceptually what these operations do—that differentiation finds rates of change and integration accumulates values—helps you use these tools correctly and interpret results. Practical robotics uses calculus concepts more than calculus calculations.

Probability and Statistics: Dealing with Uncertainty

Real robots operate in uncertain environments with noisy sensors and unpredictable dynamics. Probability and statistics provide mathematical frameworks for reasoning about and managing this uncertainty.

Sensor noise and measurement uncertainty affect every robot. Sensors do not provide perfectly accurate readings—they include random noise and systematic errors. Understanding that sensor readings distribute around true values with some statistical variation helps you design filters removing noise and estimate actual values from multiple measurements. Basic statistical concepts like mean and variance quantify this uncertainty without requiring advanced statistics.

Probability distributions describe how likely different outcomes are. If your robot’s position estimate has uncertainty, probability distribution describes where the robot probably is versus less likely positions. Normal (Gaussian) distributions, which cluster around mean values with probability decreasing for values farther from the mean, appear throughout robotics. Recognizing that distributions represent uncertainty more informatively than single values improves reasoning about robot states.

Bayes’ theorem combines prior beliefs with new evidence to update probability estimates. If your robot estimates its position with some uncertainty, then receives new sensor measurement, Bayes’ theorem mathematically describes how to update position estimate incorporating new information while accounting for sensor uncertainty. This fundamental probabilistic reasoning underlies many robotics algorithms including Kalman filters and particle filters used for robot localization.

Kalman filters fuse multiple uncertain sensor measurements into improved estimates by statistically optimal combining information. While Kalman filter mathematics involves linear algebra and probability, the key insight is that combining independent uncertain measurements reduces overall uncertainty. Libraries implement Kalman filters, but understanding their probabilistic foundation helps you tune parameters and interpret results. The concept that multiple noisy sensors together provide better information than any single sensor uses statistical reasoning.

Monte Carlo methods use random sampling to solve problems difficult to address analytically. Particle filters for robot localization represent position uncertainty through thousands of random samples (particles) that update probabilistically as robot moves and receives sensor measurements. While the mathematics underlying Monte Carlo methods involves probability theory, the intuition that random sampling can approximate complex distributions provides working understanding.

Statistical inference tests hypotheses from data. Does new sensor improve localization accuracy? Statistical tests compare performance with and without sensor, determining whether improvement is real or random variation. Basic understanding of statistical significance, confidence intervals, and experimental design helps you evaluate whether algorithm improvements are genuine or measurement noise. This empirical approach to robotics development benefits from statistical reasoning without requiring advanced statistics expertise.

Learning Mathematics for Robotics Practically

Understanding what mathematics robotics requires helps less than knowing how to learn mathematics effectively for robotics applications. Traditional mathematics education often fails roboticists because it emphasizes abstract theory before practical application.

Learn mathematics just-in-time when projects require it rather than frontloading years of study. When your line-following robot needs proportional control, learn how proportional gain affects error correction. When your robot arm requires inverse kinematics, learn the trigonometry calculating joint angles from desired positions. This contextual learning makes mathematics meaningful and memorable because you immediately apply it solving actual problems you care about.

Use problems as motivation for learning mathematical concepts. When you encounter limitations in current project—your balancing robot oscillates uncontrollably, your position estimates drift increasingly wrong, your path planning fails to find routes—these problems create motivation for learning mathematics addressing them. Problem-driven learning feels different from classroom mathematics because you pull knowledge to solve your problems rather than having information pushed at you without clear purpose.

Leverage online resources teaching mathematics for specific applications rather than abstract mathematics courses. Search “trigonometry for robotics,” “linear algebra for computer graphics,” or “calculus for control systems” rather than general mathematics courses. Applied mathematics resources teach concepts in contexts where their value is obvious, making learning more efficient and engaging than abstract presentations.

Implement mathematical concepts in code to develop intuitive understanding. Writing programs performing coordinate transformations, numerical integration, or statistical filtering builds deeper understanding than passive reading. When your code produces correct behavior, you know your mathematical understanding works correctly. When bugs appear, debugging teaches you where conceptual gaps exist.

Start with geometric intuition before diving into equations. Draw diagrams showing what mathematical relationships represent physically. Visualizing coordinate transformations as rotations and translations of coordinate axes makes matrix mathematics intuitive. Seeing integrals as areas under curves makes accumulation concepts concrete. Geometric intuition often suffices for initial implementations, with formal mathematics refining understanding later.

Use computational tools like Python, MATLAB, or Mathematica to experiment with mathematical concepts. Rather than hand-calculating matrix multiplications or solving differential equations, let software handle calculations while you focus on understanding what operations do and how to apply them. Computational mathematics develops practical skills complementing theoretical understanding. Many professional roboticists rely heavily on computational tools rather than hand calculations.

Accept that mastery develops gradually through repeated application in various contexts. You will not fully understand linear algebra after implementing one coordinate transformation or master calculus after calculating one trajectory. Mathematical maturity comes from encountering concepts repeatedly in different applications, each encounter deepening understanding. This gradual mastery through experience differs from expecting complete understanding before application.

Common Mathematical Misconceptions in Robotics

Clarifying common misconceptions about mathematics requirements prevents unnecessary anxiety while ensuring realistic expectations about what you need to learn.

“You need advanced mathematics before starting robotics” proves false. While advanced mathematics enables sophisticated work eventually, beginning robotics requires only basic mathematics most adults already know. This misconception prevents people from starting, when they could be learning robotics and mathematics together through practical application.

“Robotics mathematics is like school mathematics” misleads by suggesting abstract, context-free calculations. Robotics mathematics always serves specific purposes—calculating trajectories, transforming coordinates, filtering sensor noise. This purposeful application makes mathematics more intuitive and learnable than abstract classroom presentations suggest. Struggling with school mathematics does not predict struggling with robotics mathematics because motivation and context differ dramatically.

“You must calculate everything by hand to understand it” wastes time on mechanical calculations rather than conceptual understanding. Using calculators, spreadsheets, and programming languages to perform calculations frees attention for understanding what calculations mean and when to apply them. Professional roboticists rely extensively on computational tools. Hand calculation skill matters less than understanding what calculations accomplish and interpreting results correctly.

“All roboticists need the same mathematics” ignores that different robotics domains require different mathematical emphases. Computer vision roboticists need different mathematics than motion planning specialists or control systems engineers. Your mathematical learning should match your robotics interests rather than trying to master everything. Focusing on mathematics relevant to your work provides better returns than surveying all mathematics any roboticist might use.

“Mathematics understanding must precede implementation” reverses effective learning order. Implementing algorithms often precedes full mathematical understanding, with implementation experience motivating and enabling mathematical learning. Using libraries and following tutorials lets you accomplish tasks before understanding all underlying mathematics. This practical-first approach builds intuition supporting later theoretical understanding.

“If you are bad at mathematics, robotics is not for you” unfairly excludes people who could become excellent roboticists. Mathematics facility varies among people, but robotics success depends on many skills beyond pure mathematics. Spatial reasoning, mechanical intuition, programming ability, persistence, and creativity all contribute to robotics success. Many successful roboticists consider themselves weak at mathematics but excel through other strengths and learn necessary mathematics gradually.

Your Mathematical Learning Path

Rather than prescribing rigid sequence of mathematical topics to study, recognizing that your mathematical learning path will be unique and driven by your specific robotics interests and projects helps you plan effective learning.

Begin building robots with whatever mathematics you currently know. First projects teach you what additional mathematics would help. Attempting to frontload all potentially useful mathematics delays productive work and teaches abstract concepts you cannot yet appreciate. Direct experience building robots reveals what mathematics would enable capabilities you currently lack.

When you encounter limitations mathematics could address—calculations you cannot perform, relationships you cannot describe, or problems you cannot solve—identify specific mathematical concepts addressing those limitations. Online searches like “calculate angle between two vectors” or “smooth robot trajectory mathematics” direct you toward relevant concepts. This targeted learning provides exactly what you need when you need it.

Work through practical tutorials teaching mathematics in robotics contexts rather than general mathematics courses. A tutorial implementing particle filters teaches probability meaningfully. An inverse kinematics tutorial teaches trigonometry and linear algebra purposefully. These applied treatments make mathematics concrete and immediately useful rather than abstract and theoretical.

Implement concepts in code and verify they work correctly before worrying about formal mathematical proofs or complete theoretical understanding. Getting working implementations builds confidence and practical understanding. Theoretical understanding can develop gradually as you gain experience with working implementations. Many roboticists understand mathematics primarily through implementation experience rather than formal study.

Gradually formalize understanding through reading mathematical treatments after gaining implementation experience. Once you have working particle filter implementation, reading mathematical foundations explains why it works and how to extend it. This theory-after-practice approach makes mathematics comprehensible because you already know what concepts accomplish through implementation experience.

Recognize that mathematical learning continues throughout your robotics journey rather than completing at some point. Even experienced roboticists encounter unfamiliar mathematics when exploring new domains. This ongoing learning is feature rather than bug—robotics’ mathematical breadth ensures continual growth opportunities. Accepting that you will always be learning mathematics reduces anxiety about not knowing everything now.

The mathematics you need for robotics grows organically with your projects and ambitions. Starting requires minimal mathematics you likely already possess. As your robots become more sophisticated, mathematical tools enable capabilities beyond pure intuition and trial-and-error. Learning this mathematics incrementally, in contexts where its value is obvious, makes mathematical learning feel productive rather than burdensome. Mathematics becomes tool enabling exciting capabilities rather than barrier preventing participation. This practical, just-in-time approach to mathematical learning serves roboticists better than attempting to master abstract mathematics before building first robots. Your mathematical knowledge and robotics skills develop together, each reinforcing the other, creating upward spiral of capability where better mathematics enables more sophisticated robots and more ambitious robots motivate learning better mathematics.