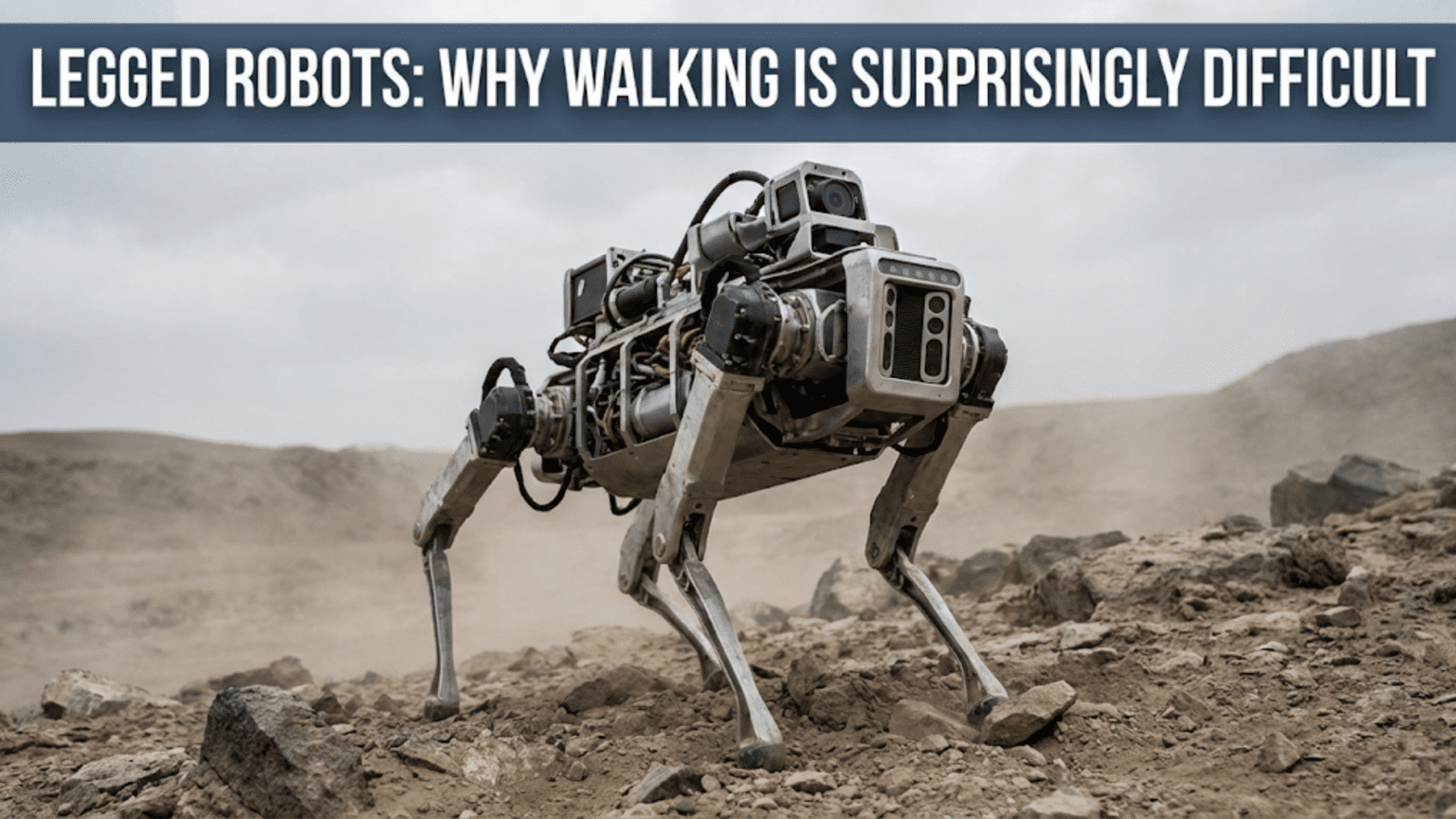

You walk without conscious thought, placing one foot in front of the other while simultaneously maintaining balance, adapting to uneven surfaces, and perhaps carrying objects or climbing stairs. This activity seems so effortless that you might assume creating a walking robot would be straightforward. After all, if wheels work well and tracks improve on wheels for difficult terrain, surely legs represent the next logical step toward ultimate mobility. Yet when you actually attempt to build even the simplest walking robot, you quickly discover that bipedal or quadrupedal locomotion presents challenges so profound that decades of intensive research have produced only limited success compared to the humble efficiency of wheels. The contrast between the apparent ease with which humans and animals walk and the extraordinary difficulty of replicating this capability in robots reveals deep insights about biological intelligence, mechanical complexity, and control theory that transform your understanding of both robotics and your own remarkable capabilities.

The fundamental challenge underlying legged locomotion is that walking inherently involves controlled falling. Unlike wheels that maintain continuous stable contact with the ground, or tracks that spread contact across long stable platforms, walking requires repeatedly lifting support away from the ground while managing the complex dynamics of an inverted pendulum balanced precariously on narrow feet. Each step transitions through unstable states where the robot could easily topple if forces, timing, or positioning errors occur. Biological systems handle this instability through sophisticated sensory feedback, rapid neural processing, and finely-tuned muscle control that evolved over millions of years. Robots attempting to replicate these capabilities must substitute engineered sensors, computer processors, and mechanical actuators that currently cannot match biological performance in power-to-weight ratio, response time, or adaptive intelligence.

This article explores why legged robots prove so challenging by examining the multiple interrelated difficulties that must be solved simultaneously for successful walking. You will learn about the stability challenges that make balance actively difficult rather than passively maintained, understand how different gaits attempt to manage these stability problems through various strategies, discover why actuator technology fundamentally limits what legged robots can achieve, and gain appreciation for the sensory and control complexity required to coordinate dozens of joints in real-time response to unpredictable terrain. Rather than discouraging you from attempting legged robot projects, this honest exploration of the genuine challenges prepares you to approach legged robotics with appropriate expectations while highlighting where current technology enables success versus where fundamental limitations still constrain what even expert teams can accomplish.

The Fundamental Stability Problem

Before examining specific engineering challenges, understanding why legged locomotion creates inherent stability difficulties helps you appreciate how deeply fundamental these problems run. Stability proves challenging not because of implementation details but because of physics and geometry that no engineering cleverness can eliminate.

Static stability requires that the center of mass falls within the support polygon formed by contact points with the ground. Imagine placing a book on a table. The book remains stable as long as its center of mass projects downward somewhere inside the area bounded by the table contact points. If you push the book toward the table edge, it becomes unstable when the center of mass projection passes outside the table boundary, at which point the book tips over. Robots with many legs can maintain static stability by ensuring their center of mass always projects inside the polygon formed by feet touching the ground. A quadruped robot standing on four feet creates a rectangular support polygon. As long as the robot’s center of mass stays within this rectangle, gravity pulls straight down through the support area and the robot remains stable. However, to walk, the robot must lift feet, which shrinks the support polygon. Lifting one leg from a quadruped reduces support from four points to three, creating a triangular support polygon. Lifting two legs leaves only two support points, creating an unstable line rather than an area. Bipedal robots standing on both feet have a small support polygon, and standing on one foot creates essentially a point rather than an area, offering minimal static stability.

Dynamic stability accepts temporary instability while controlling motion to prevent falling. When you walk, your center of mass constantly moves outside your support polygon as you transfer weight from one foot to the other. You avoid falling not by maintaining static stability but by precisely timing your foot placement to catch yourself before toppling. Each step represents controlled falling where you lean forward, begin toppling, then place your swing foot ahead of you to create a new support point that arrests the fall. This dynamic balance requires predicting where you will fall and positioning support accordingly, demanding sensory feedback about body position and motion combined with rapid control responses correcting balance continuously. Robots attempting dynamic walking must replicate this prediction and correction, requiring sensors measuring orientation and angular velocity, processors computing corrective actions in real-time, and actuators executing those corrections fast enough to prevent falling. Any delay in sensing, computation, or actuation causes the robot to fall because the unstable dynamics progress faster than the control system responds.

The inverted pendulum nature of upright posture actively fights stability rather than naturally maintaining it. A stable pendulum hangs downward with its mass below the pivot point. Disturbing a stable pendulum causes it to swing, but it naturally returns to hanging straight down without any control input. An inverted pendulum balances mass above the pivot point, creating fundamentally unstable equilibrium. Any disturbance causes the inverted pendulum to fall farther from vertical in a self-reinforcing process. Controlling an inverted pendulum requires actively opposing disturbances by moving the support point, exactly what you do when balancing on one foot by shifting your ankle position in response to lean. Walking robots function as inverted pendulums requiring continuous active control to prevent toppling. Unlike wheels or tracks that passively maintain stable contact, legged robots must actively work to avoid falling even when standing still.

Energy efficiency suffers because maintaining dynamic balance requires continuous actuation consuming power. Wheeled robots can coast to a stop and remain stationary without consuming power. Legged robots must continuously fire actuators to maintain balance even when not traveling anywhere. This constant energy expenditure for balance control reduces battery life substantially compared to passively stable wheeled robots. Even during walking, legged robots consume energy not just for forward motion but also for maintaining balance, lifting legs against gravity, and controlling complex joint motions. The energetic cost per unit distance typically exceeds wheeled robot costs by factors of three to ten, limiting practical endurance for battery-powered legged robots.

The scaling challenges become more severe as robot size increases. Small legged robots benefit from low inertia making them easier to balance because they respond quickly to control inputs and can withstand falls without damage. Larger legged robots have substantial inertia making them slower to respond to balance corrections and more dangerous when they fall. The kinetic energy involved in a large robot falling can destroy the robot and anything it lands on. This scaling reality explains why successful legged robots tend to be either very small research platforms or extremely sophisticated and expensive humanoid robots with extensive safety systems. Medium-sized legged robots occupy a difficult middle ground where inertia creates control challenges while size still prevents leveraging the robustness advantages of truly small designs.

Gait Strategies and Their Tradeoffs

Different walking patterns called gaits attempt to manage stability challenges through various strategies trading stability against speed, efficiency, and complexity. Understanding these gaits reveals how the problem-solving approaches differ and what costs each approach accepts.

Static walking gaits maintain static stability throughout the entire walking cycle by ensuring the center of mass always remains within the support polygon. Quadruped robots using static gaits lift one leg at a time while the three remaining legs form a stable triangle supporting the robot. The robot shifts its center of mass to ensure projection falls inside this triangle before lifting the next leg. This cautious approach guarantees stability at every instant but proceeds very slowly because the robot must pause to stabilize between each step. Static walking works reliably for slow inspection robots or deliberate climbing machines where speed matters less than guaranteed stability. However, the glacial pace makes static walking impractical for covering distances or responding to dynamic situations.

Dynamic walking accepts temporary instability to achieve faster gaits by allowing the center of mass to move outside the support polygon during controlled falls. Bipedal walking necessarily uses dynamic stability because standing on one foot provides minimal support polygon. The robot leans forward, falls onto the next step, and repeats this controlled falling pattern. Dynamic walking can achieve reasonable speeds approaching human walking pace, but requires sophisticated balance control preventing the controlled fall from becoming an uncontrolled tumble. The sensing, computation, and actuation requirements for dynamic walking substantially exceed static walking demands, explaining why dynamic bipedal robots remain research challenges while static quadrupeds work more reliably.

Trotting gaits used by quadrupeds lift diagonal pairs of legs simultaneously, creating a dynamic gait faster than static walking while maintaining reasonable stability. During trotting, the robot alternates between supporting on one diagonal pair and the other diagonal pair, never having all four feet on the ground simultaneously. The two support legs form a line rather than a polygon, requiring dynamic balance but providing symmetry that simplifies control compared to bipedal walking. Many quadruped robots successfully trot because this gait balances speed against achievable control complexity. Dogs and horses naturally trot at moderate speeds, suggesting this gait represents an effective compromise between stability and velocity.

Galloping represents the highest-speed quadruped gait where legs move in coordinated patterns creating brief phases with all legs off the ground simultaneously. This fully airborne flight phase enables very high speeds but demands precise timing and sophisticated control. The robot must ensure legs contact ground at exactly the right angles and times to absorb landing impacts while propelling into the next stride. Biological quadrupeds transition naturally from trotting to galloping at higher speeds, but robotic galloping remains extremely challenging requiring advanced control algorithms and robust mechanical designs withstanding repeated impact forces. Only the most sophisticated quadruped robots successfully gallop, and even these rarely match biological performance.

Running versus walking in bipedal locomotion differs fundamentally in that running includes flight phases where both feet leave the ground. Walking always maintains at least one foot in contact, while running alternates between single-foot support and complete flight. Running enables higher speeds but increases control difficulty and impact forces substantially. Building a robot that walks represents a tremendous achievement. Building one that runs requires solving the additional challenges of managing flight dynamics and impact absorption, explaining why running robots remain rare even as walking robots slowly become more capable.

Crawling gaits maintaining maximum ground contact trade speed for stability and robustness. Some multi-legged robots use insect-inspired gaits where legs move in coordinated waves while many legs always remain in contact. These gaits provide excellent stability and work reliably on rough terrain at the cost of very slow travel speeds. Crawling suits inspection robots, climbing robots, or machines operating in hazardous environments where reliability outweighs speed requirements. The additional legs required for crawling gaits add weight and complexity, but the resulting stability sometimes justifies these costs.

Actuator and Power Challenges

The mechanical systems that power joints and create motion face unique difficulties in legged robots that do not affect wheeled or tracked designs. These actuator challenges fundamentally limit what legged robots can accomplish regardless of control algorithm sophistication.

Electric motors providing rotational torque must convert this rotation into linear leg extension or other motions through transmissions, creating complexity and losses. While wheeled robots directly use rotary motor output to spin wheels, legged robots require converting rotation into the back-and-forth leg motions of walking. Gearboxes, linkages, cable drives, or other mechanisms perform this conversion, adding weight, mechanical complexity, and efficiency losses. Each mechanical component in the power transmission path introduces friction, backlash, and potential failure points. The result is that the actual leg motion achieves only a fraction of the motor’s theoretical capability after all transmission losses. Designing compact, lightweight transmissions that efficiently convert motor rotation into leg motion while withstanding the forces and accelerations of dynamic walking proves extraordinarily challenging.

Power-to-weight ratios of practical actuators fall short of biological muscle by factors of three to ten in most cases. Your leg muscles generate substantial force relative to their weight, enabling jumping, running, and climbing with agility. Electric motors achieving comparable force output weigh several times more than equivalent muscles, making robots heavier than biological systems of similar capability. This extra weight requires stronger, heavier structure to support it, creating a vicious cycle where added capability demands added mass that demands further capability. Hydraulic actuators achieve better power-to-weight ratios than electric motors but require pumps, reservoirs, and plumbing adding their own weight and complexity. Pneumatic actuators similarly need compressors and air storage. No current actuator technology matches biological muscle efficiency, forcing legged robot designers to accept either heavy robots with adequate capability or lighter robots with compromised performance.

Speed and precision requirements conflict because actuators optimized for high speed typically sacrifice force, while high-force actuators move slowly. Walking requires both rapid motion during swing phases and high forces during stance phases when supporting the robot against gravity. Achieving both in a single actuator proves difficult, forcing designers to compromise somewhere in the speed-force tradeoff. High-ratio gearboxes increase motor torque but reduce speed and increase size and weight. Low-ratio gearboxes maintain speed but limit available force. Finding the optimal balance depends on specific robot requirements, but no combination perfectly satisfies all walking demands simultaneously.

Compliance and impedance control matter tremendously for walking robots because rigid actuators create harsh impacts and poor terrain adaptation. When a rigid actuated leg contacts the ground, the impact generates high forces transmitted through the structure potentially damaging components or destabilizing balance. Biological legs use muscle compliance to absorb impacts smoothly and adapt to uneven terrain. Robots can replicate this through series elastic actuators that include springs between motors and outputs, providing mechanical compliance. However, adding compliance complicates control because the spring dynamics must be accounted for when commanding motions. Achieving appropriate stiffness that provides sufficient impact absorption without creating mushy, poorly-controlled motion requires sophisticated actuator design and control approaches still under active research.

Heat dissipation becomes critical because compact actuators working at high duty cycles generate substantial heat that must be removed to prevent damage. Motors driving walking robots operate almost continuously during walking, climbing, or balancing, generating heat proportional to electrical power consumption. Compact actuators have limited surface area for heat dissipation, making thermal management challenging. Inadequate cooling causes motors to overheat, reducing performance or causing damage. Effective cooling typically adds weight and complexity through heatsinks, fans, or liquid cooling systems. Biological muscle distributes over large tissue areas providing excellent heat dissipation that compact robot actuators cannot match, creating another fundamental challenge in replicating biological capabilities with engineered systems.

The shock loads and vibrations from walking create reliability challenges for actuators that wheel motors never face. Each footfall creates impact forces transmitting through legs to actuators. Continuous walking produces millions of these impact cycles over robot lifetimes. Designing actuators that reliably withstand this fatigue loading while maintaining precision, minimizing weight, and operating efficiently requires expensive components and careful engineering. Many legged robot projects experience premature actuator failures from insufficient attention to these fatigue issues, learning expensive lessons about the difference between occasional demonstration and reliable continuous operation.

Sensing and Perception Requirements

Legged robots require far more sophisticated sensory systems than wheeled robots because walking demands continuous awareness of body orientation, ground contact, joint positions, and environmental obstacles. The sensing challenges add substantial cost, computational load, and failure modes beyond the already difficult actuation and control problems.

Inertial measurement units measuring acceleration and rotation rates provide essential information about body orientation and motion that enables balance control. These IMUs typically combine accelerometers measuring linear acceleration along three axes with gyroscopes measuring rotation rates around three axes. Processing these six measurements reveals the robot’s orientation relative to gravity and how that orientation changes over time. Balance control algorithms use this information to detect when the robot tips away from vertical and compute corrective actions. However, IMU measurements contain noise and drift, requiring careful filtering and occasional correction from other sensors. The quality of IMU data directly affects balance control performance, making high-quality IMUs essential components for legged robots despite their cost.

Force and torque sensors in feet or legs measure ground contact forces providing crucial feedback about whether feet actually touch the ground and how much load they support. Knowing ground contact timing enables control algorithms to distinguish between stance phases when legs support the robot and swing phases when legs move freely through air. Force magnitude information reveals weight distribution across multiple legs, helping maintain appropriate loading. These contact sensors range from simple switches detecting any contact through sophisticated multi-axis force sensors measuring force magnitude and direction. More capable sensors cost more and add weight but provide richer information enabling better control. Finding appropriate sensor sophistication for specific robot requirements balances performance against cost and complexity.

Joint position encoders throughout all degrees of freedom enable the robot to know its limb configuration, which combined with body orientation provides complete pose information. Knowing exact joint angles allows computing leg positions through forward kinematics, revealing where feet are relative to the robot body. This information enables planning motions that achieve desired foot placements while avoiding ground or self-collisions. Encoders add cost and failure points at every joint, but accurate position feedback proves essential for coordinated motion. Low-quality encoders with poor resolution or significant backlash create positioning errors that accumulate across the kinematic chain, resulting in foot positions differing from computed expectations by centimeters that can cause stumbles or falls.

Environmental perception through cameras, LIDAR, or other sensors enables planning foot placement to avoid obstacles and adapt to terrain variations. While simple walking on flat surfaces might succeed with only proprioceptive sensing of the robot’s own body, real-world walking requires perceiving upcoming terrain to plan appropriate foot placements. Cameras provide rich visual information but require substantial processing to extract geometric terrain models. LIDAR directly measures distances but costs significantly more than cameras. Stereo vision systems extract depth from cameras at the cost of computational intensity. Deciding what environmental sensing to include depends on operational requirements and acceptable cost and power budgets.

Sensor fusion integrating information from diverse sensors creates unified estimates of state more accurate than any individual sensor provides. IMUs drift over time but provide excellent short-term motion information. Vision provides absolute position information but updates slowly and fails in poor lighting. Joint encoders precisely measure limb configuration but cannot detect sensor failures or mechanical damage. Combining all these information sources through Kalman filtering or similar sensor fusion techniques produces robust state estimates exploiting each sensor’s strengths while compensating for individual sensor weaknesses. Implementing sophisticated sensor fusion demands advanced algorithms and substantial computational power, adding to the overall system complexity legged robots require.

The computational requirements for processing all this sensory information in real-time while running control algorithms strain processor capabilities and power budgets. Legged robots typically require more powerful processors than wheeled robots, consuming more electrical power and generating more heat. Faster processors enable tighter control loops responding more quickly to disturbances, but cost more and drain batteries faster. Optimizing code for efficiency, choosing appropriate processors, and carefully designing control algorithms to fit available computational resources becomes essential for achieving acceptable performance within realistic power budgets.

Control Complexity and Algorithms

Even with adequate actuators and sensors, controlling all the joints in coordinated motion that produces stable walking requires sophisticated algorithms dealing with coupled dynamics, computational constraints, and robustness to disturbances. The control challenges represent some of the most difficult problems in robotics, actively researched by academic institutions and companies worldwide.

Inverse kinematics computing required joint angles to place feet at desired positions must be solved repeatedly throughout walking cycles. Given target foot positions for the next step, inverse kinematics determines what joint angles achieve those positions. For multi-joint legs, inverse kinematics can have multiple solutions or sometimes no solution, requiring algorithms that find best achievable positions when exact targets prove unreachable. Solving inverse kinematics in real-time for multiple legs while walking demands efficient computation that simple robotics platforms often cannot provide, forcing clever approximations or offline precomputation of common motion patterns.

Trajectory planning generates smooth motions between current and desired configurations that avoid obstacles, respect joint limits, and maintain balance constraints. Simply computing target positions proves insufficient because how you move between positions matters enormously for maintaining balance and avoiding damage. Trajectory planning algorithms generate continuous joint angle profiles over time that smoothly transition from current state to desired state. These trajectories must respect maximum velocity and acceleration limits, avoid self-collision of different leg segments, clear obstacles in the environment, and maintain adequate stability margins. Planning high-quality trajectories requires solving optimization problems that can be computationally expensive, forcing tradeoffs between trajectory optimality and computation time.

Zero moment point control represents one successful approach for maintaining balance during dynamic walking by ensuring ground reaction forces produce moments that keep the robot stable. The zero moment point is the location where the net moment from all forces acting on the robot equals zero. Keeping the zero moment point inside the support polygon ensures dynamic stability. ZMP control algorithms plan motions that maintain the ZMP in safe locations, providing mathematically rigorous stability guarantees. However, ZMP methods assume flat rigid ground contact, limiting their applicability to irregular terrain. They also require substantial computation for real-time trajectory optimization, restricting their use to robots with adequate computational resources.

Model predictive control looks ahead in time to predict consequences of actions, choosing control inputs that optimize future performance while satisfying constraints. MPC naturally handles the multi-input, multi-output, constrained optimization inherent in legged locomotion control. However, MPC requires computational resources that often exceed what runs in real-time on robot processors. Simplified models or reduced prediction horizons make MPC tractable but potentially sacrifice optimality. Research continues on making MPC sufficiently efficient for real-time legged robot control, with gradual progress enabling increasingly sophisticated implementations.

Machine learning approaches learn control policies from experience rather than relying on explicit models or optimization. Reinforcement learning in particular shows promise for legged locomotion, learning to walk through trial and error in simulation then transferring learned policies to real robots. These learned controllers sometimes discover gaits and strategies that human designers did not anticipate, potentially outperforming hand-crafted controllers. However, learning-based approaches require extensive training, can produce fragile policies that fail in unexpected situations, and provide limited guarantees about safety or performance. Current best practice often combines learned components with traditional control methods, using learning where it excels while maintaining explicit control structures for safety-critical elements.

Robustness to disturbances and model errors determines whether legged robots work only in laboratory conditions or operate reliably in real-world environments with unpredictable perturbations. Perfect models do not exist, actuators do not respond exactly as commanded, and unexpected pushes or terrain variations constantly disturb walking robots. Robust control design accounts for these uncertainties, maintaining stability despite imperfect knowledge and unexpected disturbances. Achieving robustness often trades off performance against reliability, accepting slower or more conservative walking to ensure the robot does not fall when conditions differ from expectations.

Why Simple Legged Robots Fail and Complex Ones Succeed

Understanding the difference between hobbyist legged robots that stumble ineffectively and professional walking robots that demonstrate impressive capabilities reveals what engineering investments prove essential versus which complications provide marginal value.

Simple hobby legged robots using hobby servos and basic microcontrollers typically walk very slowly and fall frequently because they lack the actuation power, sensing quality, and computational resources for robust dynamic walking. Hobby servos provide positioning control but have limited speed, moderate strength, and no force feedback. Basic microcontrollers run simple control loops but cannot implement sophisticated balance algorithms. The resulting robots can demonstrate walking under ideal conditions but fail as soon as terrain varies, batteries deplete, or any disturbance occurs. These simple robots still provide valuable learning experiences and can work adequately for their limited goals, but do not represent paths to genuinely capable walking machines.

Intermediate research robots with brushless motors, quality sensors, and more capable processors demonstrate much better performance through investments in actuation and computation. Using motor controllers providing precise torque control rather than position-only servos enables compliance and force control essential for reliable ground contact. Quality IMUs, force sensors, and joint encoders provide information enabling sophisticated balance algorithms. More powerful processors running advanced control code maintain stability under substantial disturbances. These upgrades typically cost ten to twenty times more than hobby components but enable performance improvements far exceeding the cost ratios, revealing that legged robotics has steep minimum capability thresholds below which success proves nearly impossible.

Professional humanoid or quadruped robots from companies like Boston Dynamics represent state-of-the-art in walking machines through extensive engineering investment in every subsystem. Custom actuators optimized for walking provide power-to-weight ratios exceeding commodity motors. Sophisticated sensors throughout the robot provide rich proprioceptive and environmental awareness. Powerful onboard computers run complex control algorithms at high update rates. Mechanical designs evolved through many iterations minimize weight while maximizing strength. These professional robots cost hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars, reflecting the engineering effort required to achieve robust real-world walking performance. The capability gap between these systems and hobby robots demonstrates that legged robotics does not yet have accessible entry points comparable to wheeled or tracked robots where modest investments produce functional results.

The learning curve for legged robotics proves extremely steep because so many difficult topics must be mastered simultaneously. You cannot build functional legged robots with only mechanical skills, or only programming ability, or only control theory knowledge. Success requires deep understanding across mechanics, electronics, sensing, control theory, and programming implemented with high-quality components and sophisticated integration. This multidisciplinary challenge explains why even universities and well-funded companies struggle with legged robotics, and why individuals or small teams rarely produce walking robots comparable to wheeled or tracked robots they might build successfully.

When Legs Make Sense Despite the Challenges

After honestly acknowledging all these difficulties, recognizing the specific situations where legs provide unique value helps you assess whether legged robots suit your applications despite their challenges.

Extreme terrain that defeats wheeled and tracked robots sometimes yields to legged locomotion because legs can step over obstacles, climb steep irregular surfaces, and operate on grounds too soft or rough for wheels or tracks. Search and rescue robots navigating disaster rubble, planetary exploration rovers traversing boulder fields, and inspection robots climbing structures all benefit from leg capabilities that no other locomotion method provides. If your application absolutely requires navigating terrain exceeding wheeled and tracked robot capabilities, accepting legged robot complexity becomes necessary rather than optional.

Specific research or educational goals focusing on understanding walking dynamics or advancing legged locomotion justify the effort despite limited practical payoff. Universities study legged robots to advance scientific understanding and develop future technologies. Students learn profound lessons about dynamics, control, and integrated system design through legged robot projects. If your goal involves learning or advancing knowledge rather than deploying practical systems, legged robots provide rich opportunities despite their difficulty. The journey teaches even when the destination remains distant.

Highly specialized applications where leg capabilities provide mission-critical value sometimes justify the cost and complexity. Military applications sometimes require walking robots for specific scenarios. Entertainment robots might need human-like motion regardless of efficiency. Medical rehabilitation devices might need replicating human walking for therapy purposes. When specific requirements mandate leg-like motion and cost proves secondary to capability, investing in legged robots makes sense even acknowledging the challenges involved.

For most hobbyists and many professionals, however, choosing wheels or tracks proves wiser because these simpler approaches accomplish most tasks while avoiding legged robot complications. Unless your specific requirements clearly demand leg capabilities or your goals explicitly focus on walking research, accepting legged complexity rarely provides good return on the substantial investment required.

Conclusion: Respect for Biological and Engineering Achievement

Legged robots reveal the profound sophistication of biological walking through the extraordinary difficulty of replicating it. Every step you take without thinking involves sensing, computation, actuation, and control that even the most advanced robots struggle to match. This realization simultaneously humbles engineering ambitions while inspiring appreciation for biological capabilities honed through millions of years of evolution. Your ability to walk deserves recognition as remarkable achievement rather than simple function taken for granted.

From an engineering perspective, legged robots represent frontier challenges where current technology still falls short of routine success. Progress continues with each research advance and commercial product improving on previous capabilities. Eventually, legged robots may become as practical and reliable as wheeled robots are today. Current reality, however, remains that building walking robots demands expertise, resources, and patience far exceeding what simpler locomotion methods require. Approaching legged robotics with appropriate expectations prevents frustration while positioning you to appreciate genuine achievements when they occur.

Your robotics journey will likely explore wheeled robots extensively before attempting even simple legged designs. This progression makes sense both pedagogically and practically because wheeled robots teach fundamental concepts while delivering reliable function. If you eventually attempt legged robots, the lessons learned from simpler platforms provide foundation making legged challenges more approachable. Understanding why wheels work helps you appreciate why legs prove difficult and what advantages might justify accepting those difficulties for specific applications.

Whether you pursue legged robots or focus on other locomotion methods, understanding the fundamental challenges reveals deep insights about robotics generally. The stability problems, actuator limitations, sensing requirements, and control complexity affecting legged robots exist throughout robotics in various forms. Studying these challenges in the extreme context of walking sharpens your engineering thinking and deepens your appreciation for the elegant solutions evolution discovered and the impressive engineering efforts gradually approaching biological capabilities through alternative paths employing today’s technologies and tomorrow’s innovations.