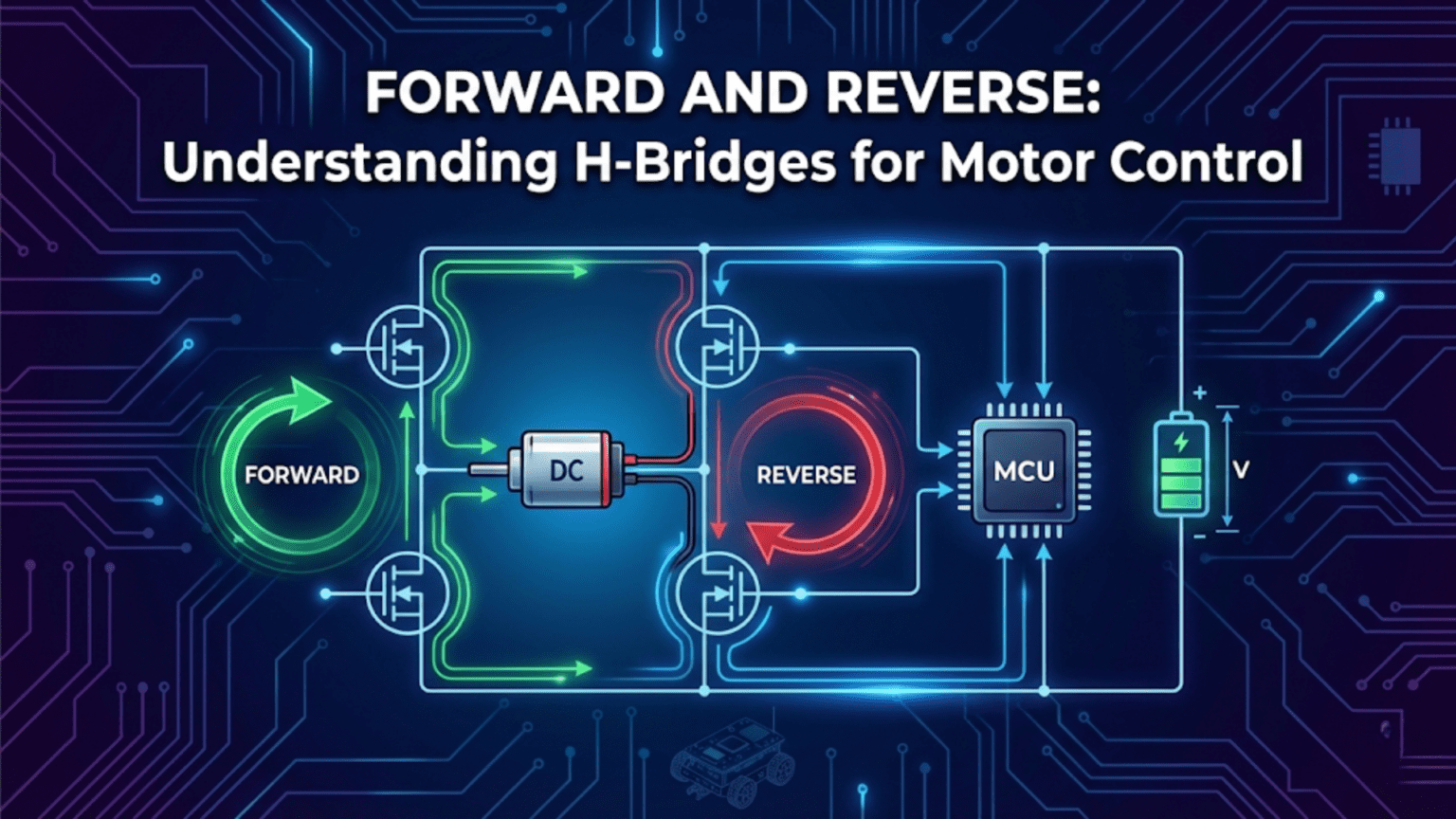

An H-bridge is a circuit containing four switching elements arranged around a motor in an H-shaped topology that enables bidirectional current flow through the motor by selectively activating different switch combinations—closing the top-left and bottom-right switches drives current in one direction (forward), while closing the top-right and bottom-left switches reverses current flow through the motor (reverse), making H-bridges the essential building block for any robot that needs to move both forward and backward rather than just spinning in one direction.

Your first robot probably moved in only one direction. Add power, it goes forward. Remove power, it stops. Simple, functional for a very limited set of tasks, but fundamentally incomplete as a robotic platform. Real robots need to reverse when they hit walls, turn by driving one wheel forward and one backward, brake quickly when stopping, and navigate complex environments that require moving in any direction at any speed. All of this requires controlling not just whether a motor receives power, but which direction current flows through it—and that requires an H-bridge.

The H-bridge solves a fundamental problem in motor control: DC motors reverse direction when you reverse the current flowing through them, but microcontrollers and batteries supply current in only one direction. You need circuitry that can take a fixed-polarity power supply and route current through a motor in either direction based on digital control signals. The H-bridge does exactly this with elegant simplicity—four switches arranged around the motor, controlled in complementary pairs to direct current either left-to-right or right-to-left through the motor windings.

This article explains H-bridges from the ground up: the circuit topology and why it works, the danger of shoot-through that can instantly destroy your driver, the practical motor driver modules that implement H-bridges in convenient packages, how to wire and program each popular module, and how to build complete motor control systems that handle speed, direction, braking, and protection. Whether you’re using a simple L298N breakout board or choosing between competing driver ICs for a custom design, this understanding of H-bridge fundamentals makes you a more capable and confident motor control engineer.

The H-Bridge Circuit: Topology and Operation

Understanding the H-bridge begins with its physical structure—four switches arranged in a specific pattern that gives the circuit both its name and its bidirectional capability.

The H-Bridge Topology Visualized

Draw the circuit and the H shape becomes immediately apparent:

+V (Battery Positive)

|

+----|----+

| |

[S1] [S2] <- Top switches

| |

+----M----+ M = DC Motor

| |

[S3] [S4] <- Bottom switches

| |

+----|----+

|

GND (Battery Negative)The motor sits in the middle of the H. Four switches—S1, S2, S3, S4—surround it. The vertical lines of the H are the power rails (positive on top, ground on bottom). The horizontal crossbar is the motor itself.

Forward Operation: S1 and S4 Closed

Close S1 (top-left) and S4 (bottom-right), keep S2 and S3 open:

+V

|

+----+----+

| |

[S1=ON] [S2=off]

| |

+→→→ M →→→+ Current flows LEFT to RIGHT through motor

| |

[S3=off] [S4=ON]

| |

+----+----+

|

GNDCurrent path: +V → S1 → Left motor terminal → through motor → Right motor terminal → S4 → GND

The motor receives current from left to right—let’s call this forward rotation.

Reverse Operation: S2 and S3 Closed

Close S2 (top-right) and S3 (bottom-left), keep S1 and S4 open:

+V

|

+----+----+

| |

[S1=off] [S2=ON]

| |

+←←← M ←←←+ Current flows RIGHT to LEFT through motor

| |

[S3=ON] [S4=off]

| |

+----+----+

|

GNDCurrent path: +V → S2 → Right motor terminal → through motor (backwards) → Left motor terminal → S3 → GND

Current now flows right to left—the motor reverses direction. Same battery, same motor, opposite rotation simply by changing which switch pair is active.

Braking: Both Bottom Switches Closed

Close S3 and S4 (both bottom), keep S1 and S2 open:

+V

|

+----+----+

| |

[S1=off] [S2=off]

| |

+----M----+ Both motor terminals connected to GND

| |

[S3=ON] [S4=ON]

| |

+----+----+

|

GNDBoth motor terminals connect to ground. As the spinning motor acts as a generator (back-EMF), the short circuit between its terminals creates strong regenerative braking—much faster stopping than simply cutting power (coast mode).

Coast mode: Open all four switches—motor terminals disconnected, motor spins down slowly due to friction only.

The Deadly Shoot-Through Condition

The most dangerous H-bridge failure mode occurs when both switches on the same side are simultaneously closed:

+V

|

+----+----+

| |

[S1=ON] [S2=off]

| |

+----M----+

| |

[S3=ON] [S4=off] <- S1 AND S3 both closed!

| |

+----+----+

|

GNDCurrent path: +V → S1 → Left motor terminal → S3 → GND

This creates a direct short circuit from battery positive to ground, bypassing the motor entirely. The switches (transistors) must carry the full short-circuit current—many times their rated capacity—for however long the condition persists. In practice: milliseconds before catastrophic failure. Transistors overheat and fail, sometimes explosively. Batteries can be damaged. PCB traces can burn.

Preventing shoot-through:

- Never simultaneously activate switches on the same side (S1+S3 or S2+S4)

- Quality H-bridge ICs include dead-time circuits that ensure both switches are OFF briefly during direction transitions

- Use established driver ICs rather than discrete transistors for beginners

From Discrete Transistors to Integrated H-Bridge ICs

While you can build H-bridges from individual MOSFETs or BJT transistors, integrated circuits combine all four switches plus protection circuitry in a single package—making them far more practical for robotics.

How IC H-Bridges Are Controlled

Most H-bridge ICs accept two control signals per motor channel, with the combination of HIGH/LOW states on these signals determining the motor state:

Standard logic table (two-input control):

| Input A | Input B | Motor State |

|---|---|---|

| LOW | LOW | Coast (Off) |

| HIGH | LOW | Forward |

| LOW | HIGH | Reverse |

| HIGH | HIGH | Brake |

Some ICs use a Direction + Enable scheme:

- Direction pin: HIGH = forward, LOW = reverse

- Enable/PWM pin: PWM signal controls speed (duty cycle = speed)

Others use Phase/Enable:

- Phase: 0 or 1 sets direction

- Enable: PWM for speed

Understanding your specific IC’s control scheme is essential before wiring—the datasheet always specifies this clearly.

Popular H-Bridge Modules for Robotics

Several motor driver modules dominate hobby robotics. Each has distinct characteristics making them suitable for different applications.

L298N: The Workhorse Module

The L298N is the most recognizable motor driver in hobby robotics—a large, heavy module with a prominent heat sink that has introduced thousands of builders to bidirectional motor control.

Specifications:

- Operating voltage: 6-35V motor supply

- Output current: 2A per channel (peak 3A)

- Number of motors: 2 (or 1 stepper motor)

- Logic voltage: 5V

- Voltage drop: ~2V (significant efficiency loss)

- Built-in 5V regulator (when VCC jumper present, for motor voltages 7-35V)

- Protection: No built-in current limiting; external protection diodes included

Pin description:

L298N Module Pins:

- ENA: Enable/PWM for Motor A (connect to PWM pin for speed control)

- IN1: Motor A input 1 (direction)

- IN2: Motor A input 2 (direction)

- OUT1/OUT2: Motor A output terminals

- IN3: Motor B input 1 (direction)

- IN4: Motor B input 2 (direction)

- ENB: Enable/PWM for Motor B

- OUT3/OUT4: Motor B output terminals

- 12V: Motor power supply (actually 6-35V despite label)

- GND: Ground (connect to Arduino GND too)

- 5V: Logic power (input if no jumper; output 5V if jumper present)Complete wiring guide:

L298N Arduino Battery / Motors

ENA → Pin 9 (PWM)

IN1 → Pin 2

IN2 → Pin 3

ENB → Pin 10 (PWM)

IN3 → Pin 4

IN4 → Pin 5

GND → GND Battery negative

12V → Battery positive (6-35V)

5V → 5V (if using L298N's regulator - remove jumper first

if motor supply > 12V)

OUT1/OUT2→ Left motor terminals

OUT3/OUT4→ Right motor terminalsComplete Arduino code for L298N:

// ===== L298N Motor Driver - Complete Implementation =====

// Motor A (Left wheel) pins

const int ENA = 9; // PWM speed control

const int IN1 = 2; // Direction

const int IN2 = 3; // Direction

// Motor B (Right wheel) pins

const int ENB = 10; // PWM speed control

const int IN3 = 4; // Direction

const int IN4 = 5; // Direction

// Motor state tracking

int leftCurrentSpeed = 0;

int rightCurrentSpeed = 0;

void setup() {

pinMode(ENA, OUTPUT);

pinMode(IN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(IN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(ENB, OUTPUT);

pinMode(IN3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(IN4, OUTPUT);

// Start with motors stopped

stopMotors();

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.println("L298N motor driver ready");

}

// ===== Core Motor Control Functions =====

// Speed: -255 (full reverse) to +255 (full forward), 0 = stop

void setMotorA(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

leftCurrentSpeed = speed;

if (speed > 0) {

// Forward

digitalWrite(IN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(ENA, speed);

} else if (speed < 0) {

// Reverse

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(IN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENA, -speed); // analogWrite needs positive value

} else {

// Brake (both inputs LOW = coast; both HIGH = brake)

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(ENA, 0);

}

}

void setMotorB(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

rightCurrentSpeed = speed;

if (speed > 0) {

digitalWrite(IN3, HIGH);

digitalWrite(IN4, LOW);

analogWrite(ENB, speed);

} else if (speed < 0) {

digitalWrite(IN3, LOW);

digitalWrite(IN4, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENB, -speed);

} else {

digitalWrite(IN3, LOW);

digitalWrite(IN4, LOW);

analogWrite(ENB, 0);

}

}

void brakeMotorA() {

// Active braking: both IN pins HIGH

digitalWrite(IN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(IN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENA, 255);

leftCurrentSpeed = 0;

}

void brakeMotorB() {

digitalWrite(IN3, HIGH);

digitalWrite(IN4, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENB, 255);

rightCurrentSpeed = 0;

}

// ===== High-Level Drive Commands =====

void stopMotors() {

setMotorA(0);

setMotorB(0);

}

void brakeMotors() {

brakeMotorA();

brakeMotorB();

}

void driveForward(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, 0, 255);

setMotorA(speed);

setMotorB(speed);

}

void driveBackward(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, 0, 255);

setMotorA(-speed);

setMotorB(-speed);

}

void turnLeft(int speed) {

// Left motor slower/stopped, right motor forward

setMotorA(speed / 2);

setMotorB(speed);

}

void turnRight(int speed) {

setMotorA(speed);

setMotorB(speed / 2);

}

void pivotLeft(int speed) {

// Left backward, right forward - spin in place

setMotorA(-speed);

setMotorB(speed);

}

void pivotRight(int speed) {

setMotorA(speed);

setMotorB(-speed);

}

// ===== Demo Sequence =====

void loop() {

Serial.println("Forward");

driveForward(180);

delay(2000);

Serial.println("Brake");

brakeMotors();

delay(500);

Serial.println("Reverse");

driveBackward(180);

delay(2000);

Serial.println("Stop");

stopMotors();

delay(500);

Serial.println("Pivot Left");

pivotLeft(150);

delay(800);

Serial.println("Pivot Right");

pivotRight(150);

delay(800);

Serial.println("Turn Left");

turnLeft(200);

delay(1000);

Serial.println("Turn Right");

turnRight(200);

delay(1000);

Serial.println("Stop - waiting 3 seconds");

stopMotors();

delay(3000);

}L298N limitations to know:

- The ~2V voltage drop means a 12V battery delivers only ~10V to motors—significant efficiency loss

- Heat sink gets warm with moderate loads—normal, but monitor at high currents

- No overcurrent protection—stalled motors can damage the IC

- The 5V on-board regulator only works when motor voltage is 7V+

L293D: The Classic Four-Channel Driver

The L293D is a smaller, lower-power H-bridge IC that comes in a DIP package fitting directly into breadboards—making it popular for prototyping.

Specifications:

- Operating voltage: 4.5-36V motor supply

- Output current: 600mA per channel (peak 1.2A)

- Number of motors: 2 (four half-H channels)

- Logic voltage: 5V

- Voltage drop: ~1.8V

- Built-in flyback diodes (the ‘D’ in L293D)

Wiring L293D:

L293D Pin Connection

Pin 1 (EN1) Arduino PWM pin (motor A speed)

Pin 2 (IN1) Arduino digital pin (direction)

Pin 3 (OUT1) Motor A terminal 1

Pin 4,5 (GND) Arduino GND and battery GND

Pin 6 (OUT2) Motor A terminal 2

Pin 7 (IN2) Arduino digital pin (direction)

Pin 8 (VS) Motor supply voltage (battery +)

Pin 9 (EN2) Arduino PWM pin (motor B speed)

Pin 10 (IN3) Arduino digital pin

Pin 11 (OUT3) Motor B terminal 1

Pin 12,13(GND)GND

Pin 14 (OUT4) Motor B terminal 2

Pin 15 (IN4) Arduino digital pin

Pin 16 (VSS) Logic supply (Arduino 5V)Code for L293D (same logic as L298N):

// L293D control - identical logic to L298N

// Just change pin assignments to match your wiring

const int EN1 = 9; // Motor A enable (PWM)

const int IN1 = 7; // Motor A direction

const int IN2 = 8; // Motor A direction

const int EN2 = 10; // Motor B enable (PWM)

const int IN3 = 5; // Motor B direction

const int IN4 = 6; // Motor B direction

void setMotorA_L293D(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

if (speed > 0) {

digitalWrite(IN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(EN1, speed);

} else if (speed < 0) {

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(IN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(EN1, -speed);

} else {

analogWrite(EN1, 0);

}

}

// setMotorB follows identical pattern with EN2, IN3, IN4When to choose L293D over L298N:

- Prototyping directly on breadboard

- Very small motors (under 500mA)

- Space-constrained designs

When L293D falls short:

- Motors drawing more than 600mA

- Any application requiring significant torque

TB6612FNG: The Modern Efficient Choice

The TB6612FNG represents a significant improvement over L298N—same functionality but with MOSFET-based switching that dramatically reduces voltage drop and heat generation.

Specifications:

- Operating voltage: 2.5-13.5V motor supply

- Output current: 1.2A continuous (3.2A peak)

- Number of motors: 2

- Logic voltage: 2.7-5.5V (3.3V and 5V compatible)

- Voltage drop: ~0.5V (vs. 2V for L298N — major advantage)

- Built-in overcurrent and thermal protection

- Standby mode for power saving

Voltage drop comparison (practical example): Running 6V motors from a 7.4V LiPo battery:

- L298N: 7.4V – 2.0V drop = 5.4V at motor (73% efficiency)

- TB6612FNG: 7.4V – 0.5V drop = 6.9V at motor (93% efficiency)

The TB6612FNG delivers substantially more power to the motor from the same battery.

Wiring TB6612FNG:

TB6612FNG Arduino Power

PWMA → PWM pin (e.g. 9)

AIN1 → Digital pin (e.g. 2)

AIN2 → Digital pin (e.g. 3)

STBY → Digital pin (e.g. 8) OR direct to 5V (always enabled)

BIN1 → Digital pin (e.g. 4)

BIN2 → Digital pin (e.g. 5)

PWMB → PWM pin (e.g. 10)

VCC → Arduino 5V

GND → Arduino GND Battery GND

VM → Battery positive (motor voltage)

AO1/AO2 → Motor A terminals

BO1/BO2 → Motor B terminalsTB6612FNG code:

// TB6612FNG Motor Driver

const int PWMA = 9;

const int AIN1 = 2;

const int AIN2 = 3;

const int STBY = 8; // Standby - must be HIGH to enable motors

const int PWMB = 10;

const int BIN1 = 4;

const int BIN2 = 5;

void setup() {

pinMode(PWMA, OUTPUT);

pinMode(AIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(AIN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(STBY, OUTPUT);

pinMode(PWMB, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN2, OUTPUT);

// Enable the driver (take out of standby)

digitalWrite(STBY, HIGH);

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.println("TB6612FNG ready");

}

void setMotorA(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

if (speed > 0) {

digitalWrite(AIN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW);

analogWrite(PWMA, speed);

} else if (speed < 0) {

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(AIN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(PWMA, -speed);

} else {

// Short brake: both inputs same state

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW);

analogWrite(PWMA, 0);

}

}

void setMotorB(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

if (speed > 0) {

digitalWrite(BIN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(BIN2, LOW);

analogWrite(PWMB, speed);

} else if (speed < 0) {

digitalWrite(BIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(BIN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(PWMB, -speed);

} else {

digitalWrite(BIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(BIN2, LOW);

analogWrite(PWMB, 0);

}

}

// Standby mode - disable all outputs and reduce power consumption

void standbyMode() {

digitalWrite(STBY, LOW);

}

void activeMode() {

digitalWrite(STBY, HIGH);

}

void loop() {

// Same high-level commands as L298N example

Serial.println("Forward at 75%");

setMotorA(191);

setMotorB(191);

delay(2000);

Serial.println("Reverse at 50%");

setMotorA(-128);

setMotorB(-128);

delay(2000);

Serial.println("Standby mode (power saving)");

standbyMode();

delay(3000);

Serial.println("Active - forward again");

activeMode();

setMotorA(200);

setMotorB(200);

delay(2000);

setMotorA(0);

setMotorB(0);

delay(1000);

}DRV8833: Dual H-Bridge for Small Motors

The DRV8833 from Texas Instruments targets small motors with excellent current sensing and protection features.

Specifications:

- Operating voltage: 2.7-10.8V

- Output current: 1.5A per channel (2A peak)

- Logic voltage: 3.3V or 5V compatible

- Voltage drop: Very low (MOSFET-based)

- Built-in overcurrent protection with automatic retry

- Sleep mode

Unique feature: xIN control scheme The DRV8833 uses a different control scheme where both input pins directly modulate the output:

| AIN1 | AIN2 | Motor State |

|---|---|---|

| PWM | LOW | Forward at PWM duty cycle |

| LOW | PWM | Reverse at PWM duty cycle |

| LOW | LOW | Coast |

| HIGH | HIGH | Brake |

// DRV8833 - different PWM scheme than L298N

const int AIN1 = 9; // PWM directly on input pins

const int AIN2 = 10;

const int BIN1 = 5;

const int BIN2 = 6;

const int SLEEP = 7; // LOW = sleep, HIGH = active

void setup() {

pinMode(AIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(AIN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(SLEEP, OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(SLEEP, HIGH); // Wake up driver

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void setMotorA_DRV8833(int speed) {

speed = constrain(speed, -255, 255);

if (speed > 0) {

analogWrite(AIN1, speed); // PWM on AIN1

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW);

} else if (speed < 0) {

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

analogWrite(AIN2, -speed); // PWM on AIN2

} else {

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW); // Coast

}

}

// Motor B follows same pattern with BIN1, BIN2Practical Considerations: Choosing and Using H-Bridges

Current Rating: The Most Critical Specification

Rule: Your H-bridge must handle the peak current your motors will ever draw—including stall current (motor stopped while power applied).

Stall current can be 5-10× the running current. A motor drawing 500mA while running might draw 3-5A when stalled. Using an H-bridge rated for 600mA with this motor risks driver failure every time the motor stalls.

How to find motor stall current:

- Check motor datasheet (stall current usually specified)

- Measure directly: connect motor, hold shaft firmly, measure current

- Estimate: stall current ≈ motor voltage ÷ motor winding resistance

Safety margin: Choose an H-bridge rated for at least 2× your motor’s stall current.

Flyback Diodes: Protecting Against Voltage Spikes

DC motors contain coils of wire. When current through a coil is suddenly interrupted, the collapsing magnetic field induces a voltage spike—potentially many times the supply voltage. Without protection, this spike flows backward into your H-bridge switches, potentially destroying them.

Protection diodes (flyback diodes, freewheeling diodes):

- Connect across each switch in the H-bridge

- Allow induced current to circulate safely rather than spiking into switches

- Many modern H-bridge ICs include these internally (L293D, TB6612FNG)

- L298N module includes external diodes on the PCB

When adding discrete transistor H-bridges: Always include 1N4001 (or similar) flyback diodes across each transistor.

Heat Management

H-bridges dissipate power as heat when driving motors:

Power dissipated:

- BJT/MOSFET switches: P = V_drop × I_motor × duty_cycle

- For L298N at 2A: P = 2V × 2A × 0.5 (50% duty cycle) = 2W per channel

2 watts sustained requires heat sinking. The L298N module includes a heat sink for this reason. For continuous high-current operation, improve cooling:

- Ensure airflow over the heat sink

- Add a small fan for heavy loads

- Use more efficient drivers (TB6612FNG) to reduce dissipation

Warning signs of thermal issues:

- Driver too hot to touch comfortably (>60°C)

- Motor speed suddenly drops (thermal protection activating)

- Burnt smell from driver

Decoupling Capacitors

Motor switching generates electrical noise that can corrupt sensor readings and microcontroller operation. Add decoupling capacitors:

Motor power supply: 100µF + 0.1µF capacitors between VM and GND

(place as close to H-bridge IC as possible)

Motor terminals: 0.1µF capacitor across each motor terminal pair

(suppresses motor commutation noise)Building a Reliable Motor Control System

Combining everything into a robust, production-quality motor controller:

// ===== Complete Robust Motor Control System =====

// Using L298N with safety features, calibration, and monitoring

// Hardware pins

const int ENA = 9, IN1 = 2, IN2 = 3;

const int ENB = 10, IN3 = 4, IN4 = 5;

// Calibration (adjust to make robot drive straight)

const float LEFT_TRIM = 1.00; // Multiply left speed by this

const float RIGHT_TRIM = 0.97; // Multiply right speed by this

// (if robot veers right, reduce RIGHT_TRIM or increase LEFT_TRIM)

// Dead zone compensation

const int DEAD_ZONE = 55; // Minimum PWM for motor movement

// Speed ramping

const int RAMP_STEP = 10;

const int RAMP_DELAY_MS = 15;

// Current state

int leftTargetSpeed = 0;

int rightTargetSpeed = 0;

int leftActualSpeed = 0;

int rightActualSpeed = 0;

bool motorsEnabled = true;

// ===== Low-Level Hardware Control =====

void applyToHardware(int leftPWM, int rightPWM) {

if (!motorsEnabled) {

analogWrite(ENA, 0);

analogWrite(ENB, 0);

return;

}

// Apply calibration trim

leftPWM = constrain((int)(leftPWM * LEFT_TRIM), -255, 255);

rightPWM = constrain((int)(rightPWM * RIGHT_TRIM), -255, 255);

// Left motor

if (leftPWM > 0) {

digitalWrite(IN1, HIGH); digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(ENA, leftPWM);

} else if (leftPWM < 0) {

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW); digitalWrite(IN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENA, -leftPWM);

} else {

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW); digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(ENA, 0);

}

// Right motor

if (rightPWM > 0) {

digitalWrite(IN3, HIGH); digitalWrite(IN4, LOW);

analogWrite(ENB, rightPWM);

} else if (rightPWM < 0) {

digitalWrite(IN3, LOW); digitalWrite(IN4, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENB, -rightPWM);

} else {

digitalWrite(IN3, LOW); digitalWrite(IN4, LOW);

analogWrite(ENB, 0);

}

}

// ===== Dead Zone Application =====

int applyDeadZone(int speed) {

if (speed == 0) return 0;

int sign = (speed > 0) ? 1 : -1;

int magnitude = abs(speed);

// Map input 1-255 to DEAD_ZONE-255

magnitude = map(magnitude, 1, 255, DEAD_ZONE, 255);

return sign * magnitude;

}

// ===== Smooth Ramping Update (call in main loop) =====

void updateMotors() {

bool needsUpdate = false;

// Ramp left motor

if (leftActualSpeed < leftTargetSpeed) {

leftActualSpeed = min(leftActualSpeed + RAMP_STEP, leftTargetSpeed);

needsUpdate = true;

} else if (leftActualSpeed > leftTargetSpeed) {

leftActualSpeed = max(leftActualSpeed - RAMP_STEP, leftTargetSpeed);

needsUpdate = true;

}

// Ramp right motor

if (rightActualSpeed < rightTargetSpeed) {

rightActualSpeed = min(rightActualSpeed + RAMP_STEP, rightTargetSpeed);

needsUpdate = true;

} else if (rightActualSpeed > rightTargetSpeed) {

rightActualSpeed = max(rightActualSpeed - RAMP_STEP, rightTargetSpeed);

needsUpdate = true;

}

if (needsUpdate) {

applyToHardware(applyDeadZone(leftActualSpeed),

applyDeadZone(rightActualSpeed));

}

}

// ===== Command Interface =====

void setMotorSpeeds(int left, int right) {

leftTargetSpeed = constrain(left, -255, 255);

rightTargetSpeed = constrain(right, -255, 255);

}

void emergencyStop() {

motorsEnabled = false;

leftTargetSpeed = 0;

rightTargetSpeed = 0;

leftActualSpeed = 0;

rightActualSpeed = 0;

applyToHardware(0, 0);

Serial.println("EMERGENCY STOP");

}

void enableMotors() {

motorsEnabled = true;

}

void setup() {

pinMode(ENA, OUTPUT); pinMode(IN1, OUTPUT); pinMode(IN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(ENB, OUTPUT); pinMode(IN3, OUTPUT); pinMode(IN4, OUTPUT);

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.println("Motor controller initialized");

}

// ===== Main Loop =====

unsigned long lastRampUpdate = 0;

void loop() {

// Update motor ramping at fixed interval

if (millis() - lastRampUpdate >= RAMP_DELAY_MS) {

updateMotors();

lastRampUpdate = millis();

}

// Example: command motor speeds from main logic

setMotorSpeeds(200, 200); // Forward

delay(2000);

setMotorSpeeds(-200, -200); // Reverse

delay(2000);

setMotorSpeeds(0, 0); // Stop

delay(1000);

}Comparison Table: H-Bridge Motor Driver Modules

| Driver | Max Voltage | Current/Channel | Voltage Drop | Efficiency | Motors | Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L293D | 36V | 600mA (1.2A peak) | ~1.8V | Low | 2 | $1-3 | Tiny motors, breadboard prototyping |

| L298N | 35V | 2A (3A peak) | ~2.0V | Low | 2 | $3-6 | Beginner projects, medium motors |

| L9110S | 12V | 800mA | ~0.5V | Medium | 2 | $1-3 | Small robots, compact designs |

| TB6612FNG | 13.5V | 1.2A (3.2A peak) | ~0.5V | High | 2 | $3-8 | Efficient hobby robots |

| DRV8833 | 10.8V | 1.5A (2A peak) | ~0.3V | High | 2 | $2-5 | Small efficient robots |

| DRV8871 | 45V | 3.6A | ~0.3V | Very High | 1 | $3-6 | High-power single motor |

| Sabertooth 2×12 | 30V | 12A | Very Low | Very High | 2 | $80+ | Large robots, heavy loads |

Common Problems and Troubleshooting

Problem: Motor Only Spins in One Direction

Symptoms: Motor runs forward with full power commands, but commands for reverse produce no movement.

Causes:

- Direction pins wired to wrong Arduino pins

- Logic table misunderstood (IN1/IN2 combination)

- One direction pin not connected

Diagnosis:

// Test all combinations directly

void testMotorDirections() {

Serial.println("Test: IN1=HIGH, IN2=LOW (should be forward)");

digitalWrite(IN1, HIGH); digitalWrite(IN2, LOW);

analogWrite(ENA, 200);

delay(2000);

Serial.println("Test: IN1=LOW, IN2=HIGH (should be reverse)");

digitalWrite(IN1, LOW); digitalWrite(IN2, HIGH);

analogWrite(ENA, 200);

delay(2000);

analogWrite(ENA, 0);

}Problem: Both Motors Always Run at Same Speed Regardless of PWM

Symptoms: Changing PWM value has no effect; motors always full speed or always stopped.

Cause: Enable pins (ENA/ENB) jumpered to 5V instead of connected to PWM pins.

Solution: Remove the jumpers on ENA and ENB, connect these pins to Arduino PWM pins.

Problem: Motor Stutters or Vibrates Instead of Running Smoothly

Symptoms: Motor makes buzzing sound; shaft rocks back and forth rather than rotating.

Causes:

- PWM value in dead zone (too low to overcome friction)

- PWM frequency too low (motor mechanically follows pulsing)

- Worn motor brushes

Solutions:

// Ensure PWM is above dead zone

const int MOTOR_MIN_PWM = 70; // Adjust experimentally

void safeMotorSpeed(int speed) {

if (speed == 0) {

analogWrite(ENA, 0);

return;

}

int safePWM = max(abs(speed), MOTOR_MIN_PWM);

analogWrite(ENA, safePWM);

}Problem: Arduino Resets When Motors Start

Symptoms: Arduino restarts or behaves erratically the moment motors activate.

Cause: Motor startup current spike drops the Arduino’s power supply voltage below its operating threshold.

Solutions:

- Use separate power supplies for motors and Arduino

- Add large capacitor (1000-4700µF) across motor power supply

- Ensure all grounds are connected (Arduino GND + motor driver GND + battery GND)

- Use heavier gauge wire for motor power connections

// Power architecture for reliable operation:

Battery (+) ──────────────────────────┬── L298N 12V

│

[Capacitor 1000µF]

│

Battery (-) ──────────────────────────┴── L298N GND ── Arduino GND

Arduino powered separately from USB or 9V battery through VinConclusion: H-Bridges as the Gateway to Full Robot Mobility

The H-bridge is the essential circuit that transforms a robot from a machine that only rolls forward into one that can truly navigate—reversing when blocked, spinning to change direction, braking quickly, and executing precise maneuvers. This four-switch topology, deceptively simple in concept, powers every mobile robot from the smallest educational kit to the largest industrial platform.

Understanding H-bridges at the circuit level—why the H shape works, what shoot-through means and why it destroys hardware, how braking differs from coasting—transforms you from someone who follows wiring diagrams into someone who understands why each connection exists. This understanding prevents mistakes, accelerates troubleshooting, and enables you to select drivers confidently rather than using whatever module appears in a tutorial.

The progression from L293D through L298N to TB6612FNG reflects real engineering trade-offs: higher efficiency costs slightly more and requires understanding standby modes; higher current handling requires better cooling; lower voltage drop requires different circuit topology. These aren’t arbitrary differences—they reflect genuine design choices with real performance consequences. Knowing which driver to choose for which application makes your robots more reliable and more capable.

The complete motor control system presented here—with dead zone compensation, calibration trim, smooth ramping, and emergency stop—represents production-quality motor control code. Each feature addresses a real limitation of simpler implementations: dead zones make low-speed control reliable; calibration trim compensates for real-world motor differences; smooth ramping protects mechanical components and creates natural-feeling motion; emergency stop provides essential safety capability.

With bidirectional motor control mastered, your robot’s movement vocabulary expands dramatically. Forward, backward, left turn, right turn, pivot left, pivot right, curved arcs, differential speed steering—all become possible through combinations of two independently controlled bidirectional motor channels. This full mobility is the foundation on which everything else in mobile robotics is built. Master the H-bridge, and you’ve mastered the essential circuit that makes mobile robots move.