Every programmer’s journey begins with a single program, and in the world of C++, that program is almost always “Hello World.” This simple program does nothing more than display the text “Hello, World!” on the screen, yet understanding how it works opens the door to comprehending how all C++ programs function. Let’s not just write this program—let’s truly understand every single character and what it means.

The tradition of beginning with a Hello World program dates back to 1978 when Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie included it in their book “The C Programming Language.” Since then, it has become the universal first program across virtually all programming languages. This tradition persists not because of nostalgia, but because Hello World accomplishes several important pedagogical goals: it verifies that your development environment works correctly, it introduces you to the basic structure of a program, and it provides immediate, visible feedback that your code is executing successfully.

Before we dive into the code itself, let’s understand what we’re trying to accomplish. When you run a C++ program, you’re asking the computer to execute a series of instructions that you’ve written. These instructions exist in a file containing text that follows C++ syntax rules. Your computer’s processor cannot directly understand this text—it only understands machine code, the binary instructions specific to your processor architecture. The compiler’s job is to translate your human-readable C++ code into the machine code that your processor can execute.

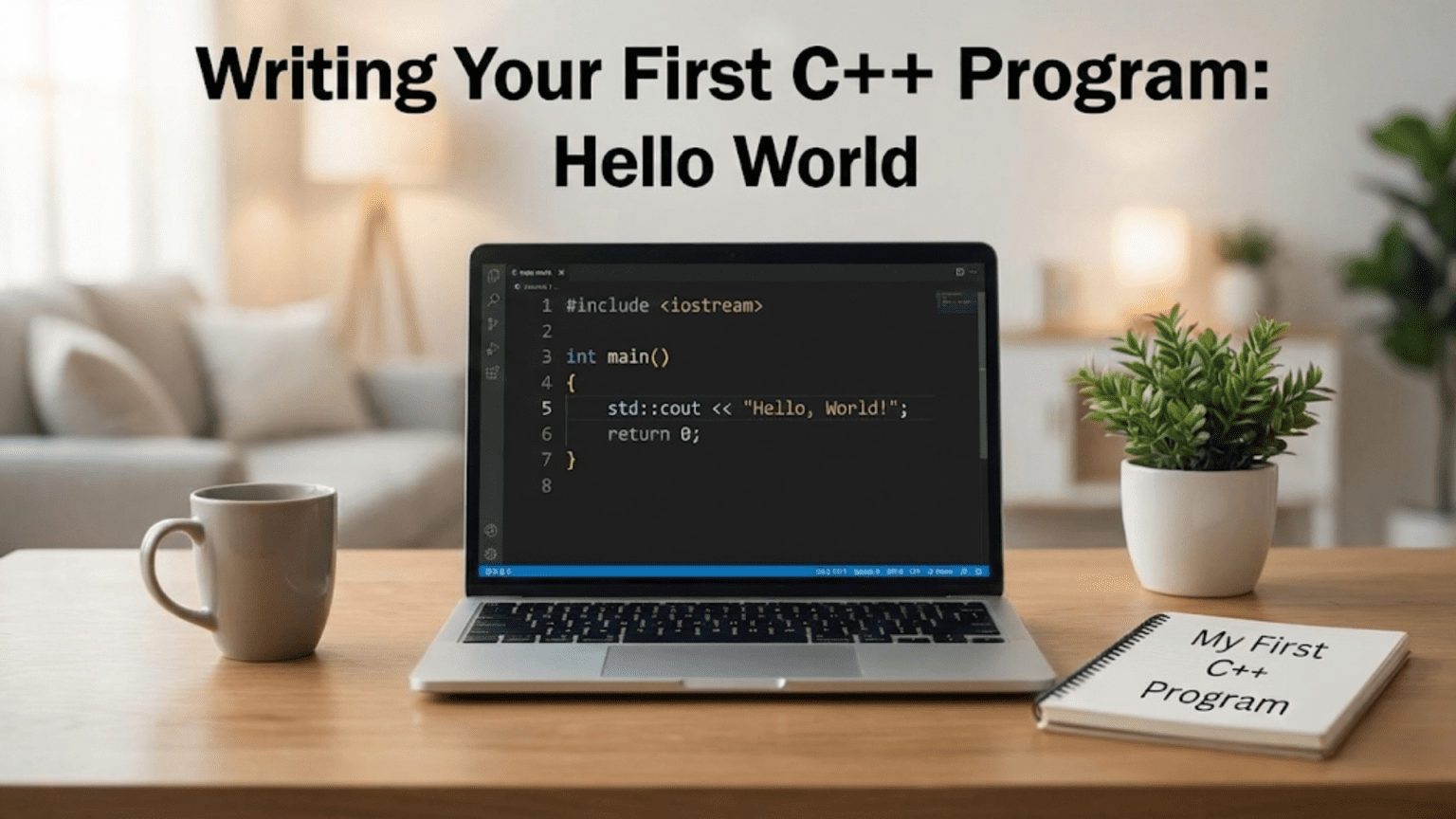

Let’s look at the complete Hello World program in C++. Open your IDE, create a new console application project, and you’ll likely see code similar to this already generated for you:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}These six lines of code contain enough information to teach you about preprocessor directives, namespaces, functions, output streams, and program execution flow. Let’s examine each component systematically, building your understanding from the ground up.

The very first line, #include <iostream>, might look cryptic, but it performs a crucial function. The # symbol at the start indicates this is a preprocessor directive—an instruction that gets processed before your actual code gets compiled. The word “include” tells the preprocessor to find a file and insert its contents at this location in your code. The angle brackets around “iostream” indicate that this is a standard library header file, one that comes with your C++ compiler rather than something you created yourself.

But what exactly is iostream, and why do we need it? The name provides a clue: it’s shorthand for “input-output stream.” This header file contains definitions for various tools that let your program communicate with the outside world—specifically, in this case, tools for displaying text on the screen and reading text from the keyboard. Without including iostream, the compiler wouldn’t know what std::cout means in the following lines, and your program wouldn’t compile. Think of including iostream like importing necessary tools into your workshop before you start a project—you need these tools available to do your work.

Header files in C++ contain declarations that tell the compiler about various programming elements that exist somewhere else. When you include iostream, you’re not including the actual implementation of output functionality—that’s linked in later. Instead, you’re including the declarations that tell the compiler “these things exist, they work in these specific ways, and you can use them in your code.” This separation between declaration and implementation is a fundamental aspect of how C++ programs are structured, though it’s not something you need to worry about deeply when you’re just starting out.

Moving to the next line, we encounter int main() followed by curly braces. This declares a function named “main,” and this particular function holds special significance in C++ programs. Every C++ program must have exactly one main function—this is where program execution begins. When you run your compiled program, the operating system looks for main and starts executing the code inside it. You can have many other functions in your program doing various tasks, but main is the entry point, the function that gets called first and controls the overall flow of your program.

The word “int” before main indicates that this function returns an integer value. But returns it to whom? When your program finishes executing, it returns a value to the operating system. By convention, returning 0 indicates that the program executed successfully without errors. Returning other values typically indicates various error conditions. This return value becomes important when you start writing programs that need to communicate their success or failure to other programs or scripts that might be running them.

The empty parentheses after main indicate that this function takes no parameters—it doesn’t need any information passed to it when it’s called. More complex programs might have a main function that accepts parameters, typically to handle command-line arguments that users can provide when running the program. For now, our simple Hello World program doesn’t need any input, so the parentheses remain empty.

The curly braces that follow the function declaration mark the beginning and end of the function’s body—the code that will execute when the function runs. Everything between the opening brace after int main() and the closing brace at the end comprises the code that runs when your program executes. Proper use of braces to delimit code blocks is fundamental to C++ syntax, and you’ll use this pattern constantly as you write more complex programs.

Now we reach the heart of our program: std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;. This single line accomplishes the actual task of displaying text on the screen, but it contains several elements worth understanding individually. Let’s break it down piece by piece.

The std:: prefix requires some explanation. When you included iostream at the top of your program, you gained access to various input and output tools. These tools reside in something called the “std namespace.” Namespaces are C++’s way of organizing code and preventing naming conflicts. Imagine if you and your neighbor both had a dog named Max—context (whose house you’re in) tells you which Max you’re referring to. Namespaces provide that context in code. The std namespace contains all the standard library functionality that comes with C++. By writing std::cout, you’re specifically referring to the cout object that lives in the std namespace.

The cout object itself is what actually handles the output. The name stands for “character output,” and it represents the standard output stream—typically, your console or terminal window. When you send data to cout, it appears on the screen. The cout object is an instance of a class defined in the iostream header, configured to display text in your console window. Understanding that cout is an object with specific behaviors becomes more important as you learn object-oriented programming, but for now, you can think of it as a tool that prints things to the screen.

The << operator might look strange if you’re thinking mathematically—it’s not performing a “less than” comparison twice. In the context of output streams, this operator is called the insertion operator or stream operator, and it means “send this data into the stream.” When you write cout << "Hello, World!", you’re saying “take this text and send it to cout, which will display it.” The operator points in the direction the data flows: from your string toward the output stream.

The text “Hello, World!” enclosed in double quotes is what programmers call a string literal. The double quotes tell the compiler that everything between them should be treated as text to be displayed exactly as written, rather than as code to be executed. You could put any text you want between these quotes, and that text would appear on the screen when your program runs. The exclamation point and comma are just characters in the string—they have no special meaning to C++ when they’re inside quotes.

Following the string, we see another << operator followed by std::endl. This endl is a stream manipulator that does two things: it outputs a newline character (moving the cursor to the next line), and it flushes the output buffer, ensuring that any text waiting to be displayed actually appears on the screen immediately. The name endl stands for “end line.” Without this, depending on your system, the text might not appear immediately, or the cursor might remain on the same line as your output, causing subsequent output to appear on the same line rather than starting fresh on a new line.

You might wonder why we need endl when we could simply include a newline character in our string, like “Hello, World!\n”. The \n escape sequence is indeed a newline character, and it would move the cursor to the next line. The difference is that endl both creates a newline and explicitly flushes the output buffer. For a simple program like Hello World, this distinction doesn’t matter much, but understanding that endl does more than just create a newline becomes relevant when you’re dealing with output buffering in more complex programs.

The semicolon at the end of the line is not optional—it’s C++’s way of indicating the end of a statement. Think of it like a period at the end of a sentence in English. In C++, most statements must end with a semicolon. Forgetting semicolons is one of the most common beginner mistakes, and the compiler will promptly inform you with an error message if you omit one. Getting into the habit of ending statements with semicolons from the start saves you from countless compiler errors as you progress.

The final line of our program, return 0;, tells the main function to finish executing and return the value 0 to the operating system. As mentioned earlier, returning 0 conventionally means “everything worked correctly.” The operating system receives this return value and can use it to determine whether your program succeeded or encountered an error. While our simple Hello World program can’t really fail in any meaningful way, including this return statement follows good practice and prepares you for writing more complex programs where return values communicate important information about how execution went.

Some C++ compilers will automatically insert return 0; at the end of main if you omit it, because the C++ standard specifies that main should return 0 by default if no return statement is present. However, explicitly writing return 0 makes your intentions clear and works consistently across all compilers and coding standards, so it’s better practice to include it.

Now that we understand what each line does, let’s talk about how to actually compile and run this program. The specific steps depend on your development environment, but the fundamental process remains the same: you write the code, save it, compile it, and run the resulting executable.

In Visual Studio on Windows, you write your code in the editor window, then press F7 or select “Build Solution” from the Build menu. Visual Studio compiles your code, and if no errors occur, it creates an executable file. You can then press Ctrl+F5 or select “Start Without Debugging” to run your program. A console window opens, displays “Hello, World!”, and waits for you to press a key before closing. This pause gives you time to see your output before the window disappears.

In Xcode on Mac, you write your code in the editor, then press Command+B to build or Command+R to build and run in one step. The output appears in Xcode’s console pane at the bottom of the window. Unlike Visual Studio’s behavior where the console window stays open, Xcode’s console remains visible after your program finishes, making it easy to see the output.

In Code::Blocks or when using command-line compilation on Linux, you write your code in whatever editor you prefer, save it with a .cpp extension, and then compile it using g++ from the terminal. If your file is named hello.cpp, you would type g++ hello.cpp -o hello to compile it, creating an executable named “hello”. Then you run it by typing ./hello, and your output appears directly in the terminal.

Understanding the compilation process helps you diagnose issues when things go wrong. When you click the build button, the compiler reads through your code, checking that it follows C++ syntax rules. If you’ve made a mistake—perhaps you forgot a semicolon, misspelled iostream, or left out a closing brace—the compiler generates an error message. These messages tell you what went wrong and usually include a line number indicating where the problem was detected.

Compiler error messages can seem cryptic at first, especially for beginners. A forgotten semicolon might generate an error message that seems unrelated to the actual problem, perhaps complaining about the line after where you forgot the semicolon. This happens because the compiler tries to make sense of your code, and when it encounters something unexpected, it can’t always pinpoint the exact mistake. Learning to read and interpret compiler errors is a crucial skill that develops with practice. Don’t be discouraged when you encounter them—every programmer, regardless of experience level, deals with compiler errors regularly.

Once your program compiles successfully, the compiler creates an executable file—a file containing machine code that your computer can run directly. This executable is what you’re actually running when you press the run button in your IDE or type the program name in the terminal. The executable file bears no resemblance to your original C++ code—it’s binary data that your processor can understand and execute. This is why compiled languages like C++ are generally faster than interpreted languages—the translation from human-readable code to machine code happens once during compilation, not every time the program runs.

Let’s explore some simple modifications to our Hello World program to solidify your understanding. Try changing the text between the quotes to display a different message. You could write your name, a favorite quote, or any other text. Compile and run the program again, and you’ll see your new message displayed. This simple experiment confirms that you understand how to modify the program and that the compilation process is working correctly.

You might try adding a second output line to display multiple lines of text:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

std::cout << "This is my first C++ program." << std::endl;

return 0;

}This modified version demonstrates that you can have multiple statements in your program, executed in order from top to bottom. Each statement performs its action—displaying a line of text—before the next statement executes. Understanding this sequential execution model is fundamental to programming: the computer does exactly what you tell it, in exactly the order you specify.

Another useful experiment involves removing std::endl and seeing what happens:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Hello, World!";

std::cout << "This is my first C++ program.";

return 0;

}When you run this version, both messages appear on the same line: “Hello, World!This is my first C++ program.” This demonstrates that cout doesn’t automatically move to a new line after each output—you must explicitly tell it to do so using either endl or the \n newline character. Understanding this behavior helps you control exactly how your output appears.

You might also experiment with commenting out code to see how different parts contribute to the program’s functionality. Comments in C++ come in two forms: single-line comments that begin with // and extend to the end of the line, and multi-line comments that begin with /* and end with */. Try adding comments to explain what each line does:

#include <iostream> // Include the input-output stream library

int main() { // Main function - program execution starts here

// Display a message on the screen

std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

return 0; // Indicate successful program completion

}Comments don’t affect how your program runs—the compiler completely ignores them. They exist to help humans understand code. Getting in the habit of writing comments that explain why you’re doing something, rather than just describing what the code does, develops good documentation practices that become increasingly valuable as you work on larger projects.

Some beginners wonder about the namespace issue and whether there’s a way to avoid typing std:: before every standard library element. There is: you can add using namespace std; after your include statement:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

cout << "Hello, World!" << endl;

return 0;

}This approach tells the compiler “unless I specify otherwise, assume that names I use come from the std namespace.” While this might seem convenient, and you’ll see it in many beginner tutorials and books, most professional C++ developers avoid using namespace declarations in header files and even in implementation files for larger projects. The reason is that it can lead to naming conflicts if you’re using multiple libraries that happen to have functions or objects with the same names. For learning purposes, either approach works fine, but understanding what std:: means helps you read professional C++ code that almost always includes the namespace qualifier.

Understanding your first C++ program opens pathways to more complex programming concepts. Every C++ program you write from this point forward will follow the same basic structure: include necessary headers, define your main function, write the code that accomplishes your goal, and return from main. As programs grow in complexity, you’ll add more headers, create additional functions beyond just main, and organize your code across multiple files, but the fundamental structure remains consistent.

The Hello World program also introduces you to the concept of libraries and using pre-existing code. The iostream library is just one of many that come with C++. As you progress, you’ll learn about libraries for working with files, performing mathematical calculations, manipulating strings, managing memory, and countless other tasks. Understanding how to include and use libraries is fundamental to productive C++ programming—you don’t need to reinvent every wheel when robust, tested libraries already exist to handle common tasks.

This simple program also demonstrates the importance of paying attention to details. Programming requires precision—you can’t write “include” instead of “#include”, you can’t forget the semicolons, and you can’t mismatch your braces. The compiler will catch these mistakes, but developing careful coding habits from the start makes programming more enjoyable and productive. Many beginners find this precision frustrating initially, but it becomes second nature with practice, and the discipline it instills makes you a better programmer across all languages.

Key Takeaways

Your first C++ program teaches fundamental concepts that apply to every program you’ll write. The structure of including necessary headers, defining the main function as your program’s entry point, using library functionality like cout for output, and returning a status code establishes patterns you’ll use throughout your C++ programming journey. Understanding what each line does, rather than just copying code that works, builds the foundation for comprehending more complex programs.

The Hello World program verifies that your development environment works correctly—if you can successfully compile and run this program, your compiler, IDE, and all associated tools are functioning properly. This confirmation lets you move forward with confidence, knowing that problems you encounter in future programs stem from your code rather than from setup issues. The immediate visual feedback of seeing your output on the screen provides satisfying proof that you can make the computer do what you want, which motivates continued learning.

Moving forward, you’ll build on these concepts, learning about variables to store data, control structures to make decisions and repeat actions, functions to organize code into reusable units, and object-oriented programming to model complex systems. But every advanced program still includes the basics you learned here: headers to access necessary functionality, a main function where execution begins, and output operations to communicate with users. Master these fundamentals, and you’re ready to explore the vast capabilities that C++ offers.