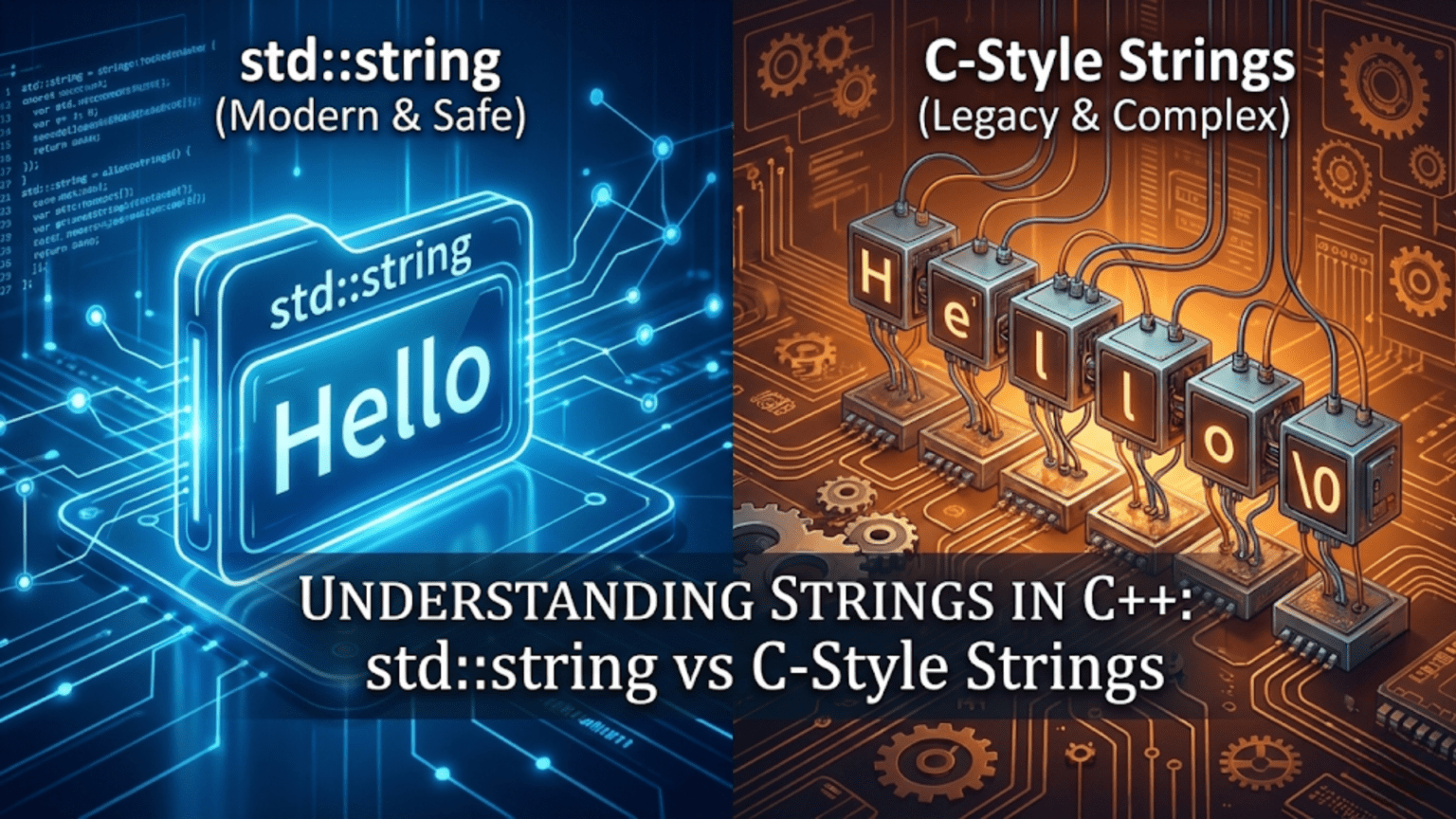

Working with text represents one of the most common tasks in programming. Whether you’re building a user interface, processing data files, formatting output, or implementing a text-based game, you’ll constantly need to store, manipulate, and display strings of characters. C++ provides two fundamentally different approaches to handling strings: modern std::string objects from the standard library, and traditional C-style character arrays inherited from the C language. Understanding both approaches—when to use each and how they differ—is essential for effective C++ programming.

The distinction between these two string types goes deeper than mere syntax differences. They represent different philosophies about memory management, safety, and convenience. C-style strings offer low-level control and compatibility with C libraries, but require careful manual memory management and are prone to errors. The std::string class wraps this complexity in a safe, convenient interface that handles memory automatically while providing a rich set of operations. As a modern C++ programmer, you’ll primarily work with std::string, but you need to understand C-style strings to work with legacy code, interact with system libraries, and appreciate the problems that std::string solves.

Let me start by explaining what strings actually are at a fundamental level. A string is a sequence of characters that represents text. At the hardware level, these characters are stored as numbers according to a character encoding scheme like ASCII, where ‘A’ is represented by the number 65, ‘B’ by 66, and so on. A string is simply a series of these character codes stored consecutively in memory, with some mechanism to indicate where the string ends.

C-style strings, also called null-terminated strings, use character arrays with a special null character (written as ‘\0’ and having the numeric value zero) marking the string’s end. Here’s a simple C-style string:

char greeting[6] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0'};This creates an array of six characters: the letters H-e-l-l-o followed by the null terminator. The null terminator is crucial—many C string functions rely on it to know where the string ends. Without it, functions would keep reading memory beyond your string until they randomly encountered a zero byte, causing unpredictable behavior.

C++ provides a convenient syntax for initializing C-style strings using string literals:

char greeting[] = "Hello"; // Compiler adds '\0' automaticallyWhen you use a string literal in double quotes, the compiler automatically allocates space for the characters plus the null terminator and initializes the array. This is more convenient than typing out each character individually, though it’s important to understand that the null terminator is always there, even though you don’t see it in the literal.

Working with C-style strings requires using functions from the C string library, accessed through the <cstring> header:

#include <cstring>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

char str1[20] = "Hello";

char str2[20] = "World";

// Get string length

int len = strlen(str1);

std::cout << "Length: " << len << std::endl; // Prints: 5

// Copy string

strcpy(str1, "Goodbye");

std::cout << str1 << std::endl; // Prints: Goodbye

// Concatenate strings

strcat(str1, " ");

strcat(str1, str2);

std::cout << str1 << std::endl; // Prints: Goodbye World

return 0;

}These functions demonstrate basic string operations, but they come with significant pitfalls. Notice that both str1 and str2 are declared with size 20, even though they initially contain much shorter strings. This extra space is necessary because functions like strcat append to the existing string—if there’s not enough space, they write beyond the array bounds, corrupting memory and causing crashes or security vulnerabilities.

Buffer overflow vulnerabilities, where strings exceed their allocated space, have been responsible for countless security breaches in software history. The C-style string functions don’t check bounds—they trust you to provide enough space. One small mistake can have catastrophic consequences:

char name[5] = "John";

strcpy(name, "Alexander"); // DANGER! "Alexander" doesn't fit in 5 bytesThis code attempts to copy nine characters plus a null terminator (ten bytes total) into an array with space for only five bytes. The extra characters overflow into adjacent memory, potentially corrupting other variables or causing a crash. The strcpy function has no way to know that name is too small—it just keeps copying until it hits the null terminator in the source string.

Enter std::string, the modern C++ solution that eliminates these problems. An std::string object manages its own memory dynamically, growing or shrinking as needed. You don’t need to worry about allocating enough space or preventing overflows—the string object handles all of this automatically. To use std::string, include the string header:

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::string greeting = "Hello";

std::string name = "Alice";

// Concatenation is easy and safe

std::string message = greeting + ", " + name + "!";

std::cout << message << std::endl; // Prints: Hello, Alice!

// String grows automatically

message += " Welcome to C++!";

std::cout << message << std::endl;

return 0;

}This code demonstrates several advantages of std::string. String concatenation uses the intuitive plus operator instead of function calls. The strings automatically allocate enough memory for their contents. You can assign and copy strings without worrying about buffer sizes. The code is cleaner, safer, and more readable than the C-style equivalent.

Creating and initializing std::string objects offers several options:

std::string s1; // Empty string

std::string s2 = "Hello"; // Initialize with string literal

std::string s3("World"); // Constructor syntax

std::string s4(10, 'x'); // 10 copies of 'x': "xxxxxxxxxx"

std::string s5 = s2; // Copy another string

std::string s6(s2, 0, 3); // Substring: first 3 chars of s2Each initialization style serves different purposes. The default constructor creates an empty string. You can initialize from a string literal, copy another string, or create strings with repeated characters. The flexibility of std::string initialization makes it easy to create the strings you need for any situation.

Accessing individual characters in a string works similarly to arrays, using square bracket notation:

std::string word = "Hello";

std::cout << word[0] << std::endl; // Prints: H

std::cout << word[1] << std::endl; // Prints: e

word[0] = 'J'; // Modify first character

std::cout << word << std::endl; // Prints: JelloThe std::string class also provides the at() method, which performs bounds checking and throws an exception if you access an invalid index:

std::string word = "Hello";

std::cout << word.at(0) << std::endl; // Safe access: H

// std::cout << word.at(10) << std::endl; // Throws exception - index out of boundsUsing at() instead of brackets trades a small performance cost for safety—the bounds check helps catch errors during development rather than allowing silent memory corruption.

String length and size information comes from several member functions:

std::string text = "Hello, World!";

std::cout << "Length: " << text.length() << std::endl; // 13

std::cout << "Size: " << text.size() << std::endl; // 13 (same as length)

std::cout << "Empty: " << text.empty() << std::endl; // false (0)

std::string empty;

std::cout << "Empty: " << empty.empty() << std::endl; // true (1)The length() and size() methods are synonymous—both return the number of characters in the string. The empty() method provides a clear, readable way to check if a string contains any characters, which is better than comparing length to zero.

String concatenation, combining multiple strings into one, is straightforward with std::string:

std::string first = "Hello";

std::string second = "World";

// Using + operator

std::string combined = first + " " + second; // "Hello World"

// Using += operator

std::string message = "Welcome";

message += " to ";

message += "C++"; // "Welcome to C++"

// Using append method

std::string sentence = "Learning";

sentence.append(" C++ ");

sentence.append("is fun!"); // "Learning C++ is fun!"Each approach has its uses. The plus operator is intuitive for building strings from multiple pieces. The += operator is efficient for adding to an existing string. The append() method provides explicit control and can append portions of strings or repeated characters.

Comparing strings for equality or ordering uses familiar operators:

std::string s1 = "apple";

std::string s2 = "banana";

std::string s3 = "apple";

if (s1 == s3) {

std::cout << "s1 and s3 are equal" << std::endl;

}

if (s1 != s2) {

std::cout << "s1 and s2 are different" << std::endl;

}

if (s1 < s2) {

std::cout << "s1 comes before s2 alphabetically" << std::endl;

}String comparison is lexicographical, meaning it follows dictionary ordering. The comparison happens character by character, and uppercase letters are different from lowercase ones according to their ASCII values (uppercase letters have smaller values and therefore “come before” lowercase in comparisons).

Searching within strings is a common operation with several methods available:

std::string text = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog";

// Find first occurrence of a substring

size_t pos = text.find("fox");

if (pos != std::string::npos) { // npos means "not found"

std::cout << "Found 'fox' at position " << pos << std::endl; // Position 16

}

// Find from a starting position

pos = text.find("the", 0);

std::cout << "First 'the': " << pos << std::endl; // Position 31 (finds "the" in "the lazy")

// Find last occurrence

pos = text.rfind("o");

std::cout << "Last 'o': " << pos << std::endl;

// Check if string contains substring

if (text.find("quick") != std::string::npos) {

std::cout << "Contains 'quick'" << std::endl;

}The find() method returns the position of the first occurrence, or std::string::npos if the substring isn’t found. Always check against npos before using the returned position. The rfind() method searches backward from the end, finding the last occurrence.

Extracting substrings creates new strings containing portions of the original:

std::string text = "Hello, World!";

// Extract substring starting at position 7, length 5

std::string sub = text.substr(7, 5); // "World"

// Extract from position to end (omit length)

std::string rest = text.substr(7); // "World!"

// Extract first few characters

std::string greeting = text.substr(0, 5); // "Hello"The substr() method takes a starting position and optionally a length. If you omit the length, it extracts from the starting position to the end of the string.

Modifying strings in place provides efficient operations for common tasks:

std::string text = "Hello World";

// Insert text at position

text.insert(5, ","); // "Hello, World"

// Erase characters

text.erase(5, 1); // Remove comma: "Hello World"

// Replace portion of string

text.replace(0, 5, "Goodbye"); // "Goodbye World"

// Clear entire string

text.clear(); // Now empty

// Check if empty

if (text.empty()) {

std::cout << "String is empty" << std::endl;

}These methods modify the string object in place rather than creating new strings, which is efficient when you need to build or adjust strings incrementally.

Converting between strings and numbers is essential for processing user input and formatting output:

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Number to string

int number = 42;

std::string numStr = std::to_string(number);

std::cout << "String: " << numStr << std::endl; // "42"

double pi = 3.14159;

std::string piStr = std::to_string(pi);

std::cout << "Pi: " << piStr << std::endl; // "3.141590"

// String to number

std::string str1 = "123";

int value = std::stoi(str1); // string to int

std::cout << "Value: " << value << std::endl; // 123

std::string str2 = "3.14";

double dbl = std::stod(str2); // string to double

std::cout << "Double: " << dbl << std::endl; // 3.14

return 0;

}The to_string() function converts numeric types to strings. The stoi(), stol(), stof(), and stod() functions convert strings to integers, longs, floats, and doubles respectively. These functions throw exceptions if the string doesn’t contain a valid number, so you should handle potential errors in production code.

Reading strings from input requires understanding the difference between formatted and unformatted input:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

int main() {

std::string name;

// Read single word (stops at whitespace)

std::cout << "Enter your first name: ";

std::cin >> name;

std::cout << "Hello, " << name << std::endl;

// Read entire line including spaces

std::cin.ignore(); // Ignore leftover newline

std::string fullName;

std::cout << "Enter your full name: ";

std::getline(std::cin, fullName);

std::cout << "Hello, " << fullName << std::endl;

return 0;

}The extraction operator (>>) reads until it encounters whitespace, making it suitable for reading single words but not phrases. The getline() function reads an entire line including spaces, stopping only at the newline character. This makes it better for reading names, sentences, or any input that might contain spaces.

Iterating through string characters enables processing or analysis:

std::string text = "Hello";

// Using index-based loop

for (size_t i = 0; i < text.length(); i++) {

std::cout << text[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Using range-based for loop (modern C++)

for (char c : text) {

std::cout << c << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Modify characters

for (char& c : text) { // Note the reference

c = toupper(c);

}

std::cout << text << std::endl; // "HELLO"The range-based for loop is cleaner and safer than index-based loops for simple iteration. Using a reference (char&) allows you to modify the characters in place.

Understanding the relationship between std::string and C-style strings helps when interfacing with C libraries or legacy code:

std::string modern = "Hello World";

// Convert std::string to C-string

const char* cstr = modern.c_str();

printf("C-style: %s\n", cstr); // Use with C functions

// Convert C-string to std::string

char oldStyle[] = "Legacy Code";

std::string modern2 = oldStyle; // Automatic conversion

std::string modern3(oldStyle); // Explicit conversionThe c_str() method returns a pointer to a null-terminated character array containing the string’s contents. This pointer is valid only as long as the string object exists and isn’t modified. You can construct std::string objects from C-style strings, which copies the characters into the new string object.

Let me show you a practical example that demonstrates many string operations—a simple text processing program:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

void analyzeText(const std::string& text) {

std::cout << "\n=== Text Analysis ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Length: " << text.length() << " characters" << std::endl;

// Count words (simple version - splits on spaces)

int wordCount = 1;

for (char c : text) {

if (c == ' ') wordCount++;

}

std::cout << "Words: " << wordCount << std::endl;

// Count vowels

int vowelCount = 0;

std::string vowels = "aeiouAEIOU";

for (char c : text) {

if (vowels.find(c) != std::string::npos) {

vowelCount++;

}

}

std::cout << "Vowels: " << vowelCount << std::endl;

// Find and report specific words

if (text.find("C++") != std::string::npos) {

std::cout << "Contains 'C++'" << std::endl;

}

}

std::string formatName(const std::string& firstName, const std::string& lastName) {

return lastName + ", " + firstName;

}

int main() {

std::string text;

std::cout << "Enter some text: ";

std::getline(std::cin, text);

analyzeText(text);

std::string first, last;

std::cout << "\nEnter first name: ";

std::cin >> first;

std::cout << "Enter last name: ";

std::cin >> last;

std::string formatted = formatName(first, last);

std::cout << "Formatted: " << formatted << std::endl;

return 0;

}This program demonstrates reading strings, analyzing their contents, searching for substrings, and building formatted output. It shows how std::string makes text processing straightforward and safe.

Performance considerations matter when working with strings extensively. String concatenation in a loop can be inefficient:

// Inefficient - creates many temporary strings

std::string result;

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

result = result + "x"; // Creates new string each iteration

}

// More efficient - modifies string in place

std::string result;

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

result += "x"; // Appends in place

}

// Most efficient for repeated appends

std::string result;

result.reserve(1000); // Pre-allocate space

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

result += "x";

}The reserve() method pre-allocates memory, avoiding multiple reallocations as the string grows. For building large strings, this can significantly improve performance.

Common string mistakes include assuming one character equals one byte in all encodings:

std::string emoji = "😀"; // Multi-byte UTF-8 character

std::cout << "Length: " << emoji.length() << std::endl; // Might print 4, not 1Unicode characters in UTF-8 encoding can occupy multiple bytes. The length() method returns the number of bytes, not the number of visible characters. Properly handling Unicode requires understanding encodings and potentially using specialized libraries.

Another mistake is comparing strings case-insensitively without converting first:

std::string s1 = "Hello";

std::string s2 = "hello";

if (s1 == s2) { // false - case sensitive

std::cout << "Equal" << std::endl;

}

// Convert both to lowercase for case-insensitive comparison

std::string s1Lower, s2Lower;

for (char c : s1) s1Lower += tolower(c);

for (char c : s2) s2Lower += tolower(c);

if (s1Lower == s2Lower) { // true

std::cout << "Equal (case-insensitive)" << std::endl;

}Standard string comparison is case-sensitive. For case-insensitive comparison, convert both strings to the same case first.

Key Takeaways

C++ offers two string types: C-style null-terminated character arrays and std::string objects. C-style strings require manual memory management and are prone to buffer overflows but provide low-level control and C compatibility. The std::string class provides automatic memory management, safety, and convenience through a rich set of member functions—it’s the preferred choice for modern C++ development.

String operations with std::string are intuitive and safe. Concatenation uses the + and += operators, comparison uses standard comparison operators, and member functions like find(), substr(), insert(), and replace() provide powerful manipulation capabilities. Converting between strings and numbers uses to_string() for numbers to strings and stoi()/stod() family for strings to numbers.

Always use getline() for reading strings that might contain spaces, and prefer range-based for loops for iterating through characters. When interfacing with C code, use c_str() to get a C-style string from an std::string. For performance-critical code that builds large strings, use reserve() to pre-allocate memory. Understanding both string types prepares you to work with modern C++ while maintaining compatibility with legacy code and system libraries.