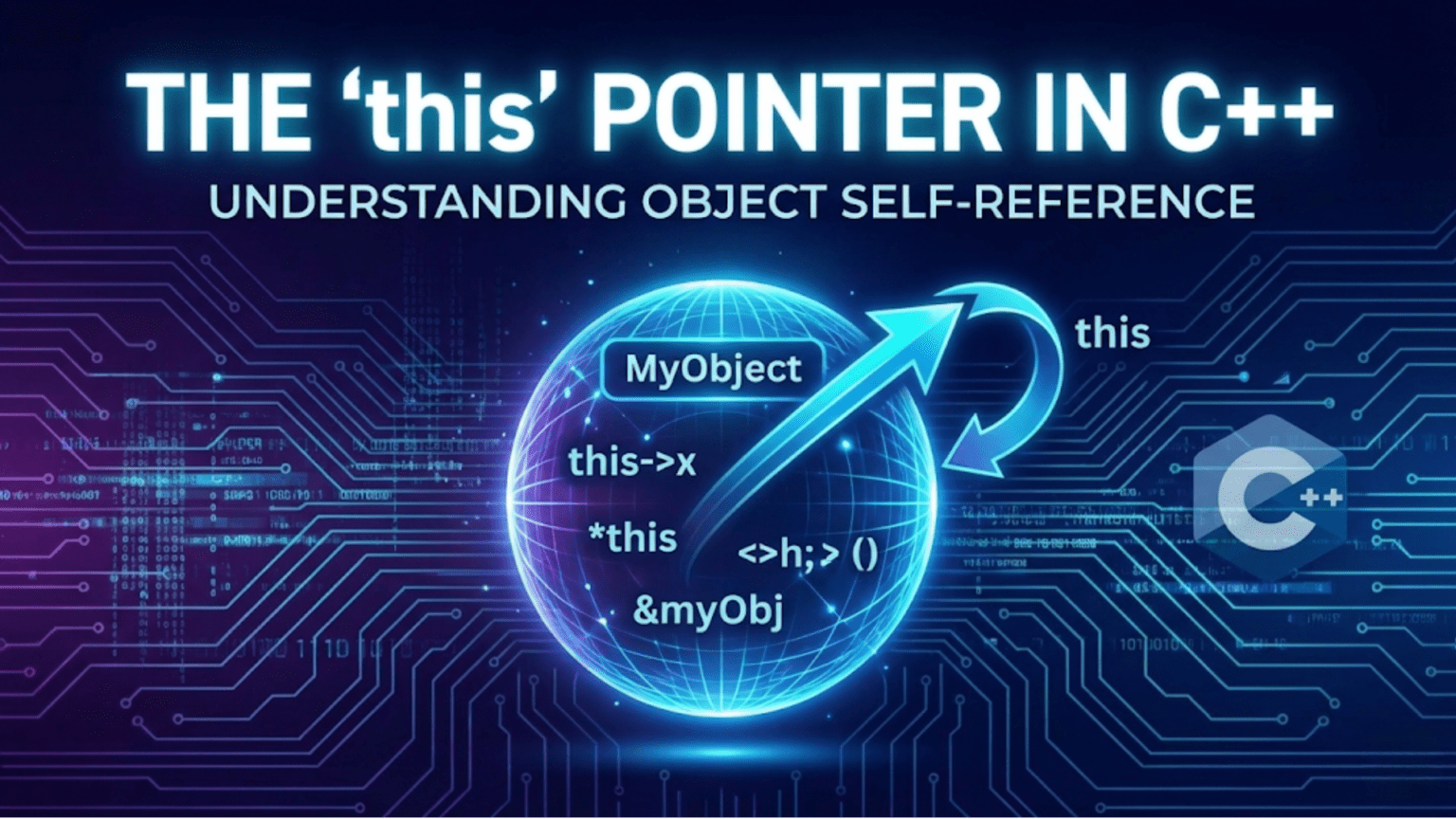

When you call a member function on an object, the function somehow knows which object it is working with so it can access that specific object’s member variables. If you create ten BankAccount objects and call the deposit method on the third one, that method needs to modify the third object’s balance, not the first object’s balance or some random memory location. But how does the member function know which object called it? The answer lies in a hidden parameter that the compiler automatically passes to every non-static member function, a special pointer called this that points to the object on which the function was called. Understanding the this pointer reveals the mechanism behind member functions and enables advanced techniques like method chaining, resolving naming conflicts, and implementing certain design patterns.

Think of the this pointer like a name badge you receive at a conference. When you attend a session, the speaker does not need to ask “Who are you?” because your name badge identifies you. Similarly, when a member function executes, it does not need to wonder which object it belongs to because the this pointer automatically identifies the current object. Just as you might reference your own name badge to introduce yourself or verify your identity, member functions use the this pointer to reference the current object when needed. In most cases, you can access member variables directly without explicitly using this, just as conference attendees rarely need to point to their own name badges. But certain situations require explicitly using this to clarify intent or enable specific programming patterns.

The power of understanding this comes from recognizing both when it works implicitly and when you need to use it explicitly. The compiler automatically generates code to pass this to every member function call, making member variable access natural and intuitive. Most of the time, you write code that implicitly uses this without typing the keyword. But when parameter names shadow member variables, when you need to return a reference to the current object for method chaining, when you want to pass the current object to another function, or when you need to compare object identity, explicitly using this becomes necessary and valuable. Mastering the this pointer transforms you from someone who vaguely understands how member functions work to someone who deeply understands the object-oriented mechanism and can leverage it for elegant designs.

Let me start by showing you how this works implicitly in normal member function calls and then demonstrate situations where using it explicitly clarifies code or enables important patterns:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Person {

private:

std::string name;

int age;

public:

Person(const std::string& personName, int personAge)

: name(personName), age(personAge)

{

std::cout << "Person created: " << name << std::endl;

}

// Member function with implicit this usage

void displayImplicit() const {

// name and age are accessed through implicit this

// Compiler translates to: this->name and this->age

std::cout << "Name: " << name << ", Age: " << age << std::endl;

}

// Member function with explicit this usage

void displayExplicit() const {

// Explicitly use this pointer to access members

std::cout << "Name: " << this->name << ", Age: " << this->age << std::endl;

}

// Show the this pointer's value

void showThisPointer() const {

std::cout << "this pointer value: " << this << std::endl;

std::cout << "Address of object: " << this << std::endl;

}

void celebrateBirthday() {

// Implicitly uses this->age

age++;

std::cout << name << " is now " << age << " years old" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Person person1("Alice", 25);

Person person2("Bob", 30);

std::cout << "\n=== Person 1 ===" << std::endl;

person1.displayImplicit();

person1.displayExplicit();

person1.showThisPointer();

std::cout << "\n=== Person 2 ===" << std::endl;

person2.displayImplicit();

person2.displayExplicit();

person2.showThisPointer();

std::cout << "\n=== Birthday Celebration ===" << std::endl;

person1.celebrateBirthday();

return 0;

}When you call person one dot display implicit, the compiler automatically passes the address of person one as the this pointer to the display implicit function. Inside the function, accessing name is equivalent to accessing this arrow name, though the this is implicit and you do not need to type it. The show this pointer method prints the value of this, which you will see matches the memory address of the object. When you call the same method on person two, this contains person two’s address instead. This mechanism is how member functions know which object’s data to access, even though you write the function only once in the class definition.

One of the most common situations requiring explicit this usage is resolving naming conflicts when parameters have the same names as member variables:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Rectangle {

private:

double width;

double height;

public:

// Constructor with naming conflict - parameters shadow members

Rectangle(double width, double height) {

// Must use this-> to distinguish member from parameter

this->width = width; // this->width is the member variable

this->height = height; // height parameter assigns to this->height member

std::cout << "Rectangle created: " << this->width << " x " << this->height << std::endl;

}

// Setter with naming conflict

void setDimensions(double width, double height) {

// Without this->, width would refer to the parameter, not the member

this->width = width;

this->height = height;

std::cout << "Dimensions updated to: " << this->width << " x " << this->height << std::endl;

}

// Alternative without naming conflict - different parameter names

void setSize(double w, double h) {

// No conflict, so this-> is optional

width = w; // Implicitly this->width = w

height = h; // Implicitly this->height = h

}

double getArea() const {

return width * height; // Implicit this->width * this->height

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "Rectangle: " << width << " x " << height

<< " (Area: " << getArea() << ")" << std::endl;

}

};

class Point {

private:

double x;

double y;

public:

// Using this-> for clarity even without conflict

Point(double x, double y) : x(x), y(y) {

std::cout << "Point created at (" << this->x << ", " << this->y << ")" << std::endl;

}

void moveTo(double x, double y) {

std::cout << "Moving from (" << this->x << ", " << this->y << ")";

this->x = x;

this->y = y;

std::cout << " to (" << this->x << ", " << this->y << ")" << std::endl;

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ")";

}

};

int main() {

Rectangle rect(5.0, 10.0);

rect.display();

rect.setDimensions(8.0, 12.0);

rect.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

Point point(3.0, 4.0);

point.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

point.moveTo(10.0, 15.0);

point.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}When the Rectangle constructor has parameters named width and height that match the member variable names, the parameters shadow the member variables within the function scope. Writing just width would refer to the parameter, not the member. Using this arrow width explicitly accesses the member variable, disambiguating the reference. This pattern appears frequently in constructors and setters where using parameter names that match members makes the code self-documenting. Some programmers prefer different parameter names like w and h to avoid needing this, while others prefer matching names with explicit this for clarity. Both approaches work, and the choice comes down to personal or team preference.

Returning a reference to the current object using asterisk this enables method chaining, where you can call multiple methods on the same object in a single statement:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class BankAccount {

private:

std::string accountNumber;

double balance;

public:

BankAccount(const std::string& accNum, double initialBalance)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(initialBalance)

{

std::cout << "Account created: " << accountNumber

<< " with balance $" << balance << std::endl;

}

// Return reference to current object for chaining

BankAccount& deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

std::cout << "Deposited $" << amount << ". Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

}

return *this; // Return reference to current object

}

// Return reference for chaining

BankAccount& withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount > 0 && amount <= balance) {

balance -= amount;

std::cout << "Withdrew $" << amount << ". Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Invalid withdrawal" << std::endl;

}

return *this;

}

// Return reference for chaining

BankAccount& applyInterest(double rate) {

double interest = balance * rate;

balance += interest;

std::cout << "Interest applied: $" << interest << ". Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

return *this;

}

void displayBalance() const {

std::cout << "Account " << accountNumber << " balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

}

};

class StringBuilder {

private:

std::string text;

public:

StringBuilder() : text("") {}

// Method chaining for string building

StringBuilder& append(const std::string& str) {

text += str;

return *this;

}

StringBuilder& appendLine(const std::string& str) {

text += str + "\n";

return *this;

}

StringBuilder& clear() {

text.clear();

return *this;

}

std::string toString() const {

return text;

}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Method Chaining with BankAccount ===" << std::endl;

BankAccount account("ACC001", 1000.0);

// Method chaining - multiple operations in one statement

account.deposit(500).withdraw(200).applyInterest(0.05).deposit(100);

std::cout << std::endl;

account.displayBalance();

std::cout << "\n=== Method Chaining with StringBuilder ===" << std::endl;

StringBuilder builder;

// Chain multiple append operations

std::string result = builder

.append("Hello, ")

.append("World!")

.appendLine("")

.append("This is ")

.append("method chaining.")

.toString();

std::cout << result << std::endl;

return 0;

}When deposit returns asterisk this, it returns a reference to the current BankAccount object. The calling code receives a reference to the same object it just called deposit on, enabling immediately calling another method on the returned reference. This creates the fluent interface pattern where method calls chain together naturally, reading almost like sentences. The StringBuilder example shows this pattern used for constructing strings incrementally, where each append returns a reference to the builder itself, allowing the next append to work on the same object. Without returning asterisk this, you would need to make separate statements for each method call, making the code more verbose and less expressive.

The this pointer enables passing the current object to other functions or storing it in data structures:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class Task; // Forward declaration

class TaskManager {

private:

std::vector<Task*> tasks;

public:

void registerTask(Task* task) {

tasks.push_back(task);

std::cout << "Task registered with manager" << std::endl;

}

void displayAllTasks() const; // Defined after Task class

int getTaskCount() const {

return tasks.size();

}

};

class Task {

private:

std::string description;

bool completed;

TaskManager* manager;

public:

Task(const std::string& desc, TaskManager* mgr)

: description(desc), completed(false), manager(mgr)

{

std::cout << "Task created: " << description << std::endl;

// Pass this pointer to manager to register current task

if (manager != nullptr) {

manager->registerTask(this);

}

}

void complete() {

completed = true;

std::cout << "Task completed: " << description << std::endl;

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "[" << (completed ? "X" : " ") << "] " << description << std::endl;

}

bool isCompleted() const {

return completed;

}

};

// Define TaskManager method after Task is complete

void TaskManager::displayAllTasks() const {

std::cout << "\n=== All Tasks ===" << std::endl;

for (const auto* task : tasks) {

task->display();

}

}

class Student {

private:

std::string name;

int id;

public:

Student(const std::string& studentName, int studentId)

: name(studentName), id(studentId)

{

std::cout << "Student created: " << name << std::endl;

}

// Pass this pointer to another function

void enrollInCourse(void (*enrollFunc)(Student*)) {

std::cout << "Enrolling " << name << "..." << std::endl;

enrollFunc(this); // Pass current object to the function

}

std::string getName() const { return name; }

int getId() const { return id; }

};

void processEnrollment(Student* student) {

std::cout << "Processing enrollment for " << student->getName()

<< " (ID: " << student->getId() << ")" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Task Management ===" << std::endl;

TaskManager manager;

// Tasks register themselves with manager using this pointer

Task task1("Write documentation", &manager);

Task task2("Review code", &manager);

Task task3("Fix bugs", &manager);

task1.complete();

task2.complete();

manager.displayAllTasks();

std::cout << "Total tasks: " << manager.getTaskCount() << std::endl;

std::cout << "\n=== Student Enrollment ===" << std::endl;

Student student("Alice Johnson", 1001);

student.enrollInCourse(processEnrollment);

return 0;

}The Task constructor passes this to the TaskManager’s register task method, allowing the manager to store a pointer to the newly created task. This pattern enables objects to register themselves with managers, observers, or containers during construction. The Student class demonstrates passing this to a function pointer, where enroll in course passes the current student object to whatever enrollment processing function is provided. These patterns show how this enables objects to integrate themselves into larger systems by passing references to themselves to other components.

Comparing object identity using this enables checking if two pointers or references point to the same object:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Employee {

private:

std::string name;

int employeeId;

public:

Employee(const std::string& n, int id)

: name(n), employeeId(id)

{

std::cout << "Employee created: " << name << " (ID: " << employeeId << ")" << std::endl;

}

// Check if this object is the same as another

bool isSameEmployeeAs(const Employee& other) const {

return this == &other; // Compare addresses

}

// Compare by value (same data) vs identity (same object)

bool hasIdenticalDataAs(const Employee& other) const {

return employeeId == other.employeeId && name == other.name;

}

std::string getName() const { return name; }

int getId() const { return employeeId; }

void display() const {

std::cout << "Employee: " << name << " (ID: " << employeeId << ")" << std::endl;

}

};

class Node {

private:

int data;

Node* next;

public:

Node(int value) : data(value), next(nullptr) {

std::cout << "Node created with value: " << data << std::endl;

}

void setNext(Node* nextNode) {

// Prevent self-referential loops

if (nextNode == this) {

std::cout << "Error: Cannot point to self!" << std::endl;

return;

}

next = nextNode;

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "Node value: " << data;

if (next != nullptr) {

std::cout << " -> points to another node";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Object Identity Comparison ===" << std::endl;

Employee emp1("Alice Johnson", 1001);

Employee emp2("Bob Smith", 1002);

Employee emp3("Alice Johnson", 1001); // Same data as emp1, different object

// Compare emp1 with itself

std::cout << "\nComparing emp1 with itself:" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Same object? " << (emp1.isSameEmployeeAs(emp1) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

// Compare emp1 with emp2

std::cout << "\nComparing emp1 with emp2:" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Same object? " << (emp1.isSameEmployeeAs(emp2) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

// Compare emp1 with emp3 (same data, different objects)

std::cout << "\nComparing emp1 with emp3:" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Same object? " << (emp1.isSameEmployeeAs(emp3) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

std::cout << "Identical data? " << (emp1.hasIdenticalDataAs(emp3) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

std::cout << "\n=== Preventing Self-Reference ===" << std::endl;

Node node1(10);

Node node2(20);

node1.setNext(&node2); // OK

node1.setNext(&node1); // Prevents self-reference using this

return 0;

}The is same employee as method compares this with the address of other to determine if they are the same object. This differs from comparing values, where two different objects might contain identical data. The has identical data as method compares values, showing the distinction between object identity and value equality. The Node class uses this to prevent setting next to point to itself, which would create a problematic self-referential loop. These patterns demonstrate how this enables reasoning about object identity rather than just object values.

Understanding that this is const in const member functions helps explain why const member functions cannot modify member variables:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Counter {

private:

int count;

mutable int accessCount; // mutable allows modification in const methods

public:

Counter() : count(0), accessCount(0) {}

// Non-const member function - this is Counter*

void increment() {

count++; // OK - can modify members

std::cout << "Count incremented to: " << count << std::endl;

}

// Const member function - this is const Counter*

int getCount() const {

accessCount++; // OK - mutable member can be modified

// count++; // Error! Cannot modify non-mutable member in const function

return count; // OK - can read members

}

// Const member function

void display() const {

// In this function, this has type: const Counter*

// Cannot do: this->count = 100; // Error!

std::cout << "Count: " << count << " (accessed " << accessCount << " times)" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Counter counter;

counter.increment();

counter.increment();

std::cout << "Current count: " << counter.getCount() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Current count: " << counter.getCount() << std::endl;

counter.display();

// Const object can only call const member functions

const Counter constCounter;

std::cout << "Const counter value: " << constCounter.getCount() << std::endl;

// constCounter.increment(); // Error! Cannot call non-const function on const object

return 0;

}In a const member function, this has type const class name asterisk instead of just class name asterisk. This const qualification on this prevents modifying member variables through this, which is why const member functions cannot change object state. The mutable keyword provides an exception for members that need modification even in const contexts, typically for implementation details like caching or statistics that do not affect the logical state of the object.

Static member functions do not receive a this pointer because they are not called on specific object instances:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class MathUtils {

public:

// Static member function - no this pointer

static int add(int a, int b) {

// Cannot use this pointer here - no object instance

// return this->someValue; // Error! Static functions have no this

return a + b;

}

static double square(double x) {

return x * x;

}

};

class Counter {

private:

int value;

static int totalInstances;

public:

Counter(int v) : value(v) {

totalInstances++;

}

// Non-static member function - has this pointer

void increment() {

value++; // Accesses this->value

}

int getValue() const {

return value; // Returns this->value

}

// Static member function - no this pointer

static int getTotalInstances() {

// Can access static members

return totalInstances;

// Cannot access instance members

// return value; // Error! No this pointer, so no way to access instance member

}

};

int Counter::totalInstances = 0;

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Static Functions ===" << std::endl;

// Call static function without object

int sum = MathUtils::add(5, 3);

std::cout << "5 + 3 = " << sum << std::endl;

std::cout << "\n=== Counter Example ===" << std::endl;

Counter c1(10);

Counter c2(20);

Counter c3(30);

std::cout << "Total instances: " << Counter::getTotalInstances() << std::endl;

return 0;

}Static member functions belong to the class itself rather than to individual objects, so the compiler does not pass a this pointer to them. They can access static members that belong to the class, but they cannot access instance members because there is no this pointer pointing to a specific object. When you call Math Utils colon colon add, no object is involved, so there is no this pointer. This distinction between static and non-static member functions clarifies when this exists and when it does not.

Let me show you a comprehensive example that demonstrates various uses of this pointer working together in a realistic application:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class Product {

private:

std::string name;

double price;

int stock;

public:

Product(const std::string& name, double price, int stock)

: name(name), price(price), stock(stock)

{

std::cout << "Product created: " << this->name << std::endl;

}

// Method chaining with this

Product& setPrice(double price) {

this->price = price;

std::cout << this->name << " price set to $" << this->price << std::endl;

return *this;

}

Product& adjustStock(int amount) {

this->stock += amount;

std::cout << this->name << " stock adjusted by " << amount

<< " to " << this->stock << std::endl;

return *this;

}

Product& applyDiscount(double percentage) {

this->price *= (1 - percentage / 100.0);

std::cout << this->name << " discounted to $" << this->price << std::endl;

return *this;

}

bool isSameProduct(const Product& other) const {

return this == &other; // Identity comparison

}

void display() const {

std::cout << this->name << " - $" << this->price

<< " (Stock: " << this->stock << ")" << std::endl;

}

std::string getName() const { return name; }

double getPrice() const { return price; }

};

class ShoppingCart {

private:

std::vector<Product*> items;

std::string customerName;

public:

ShoppingCart(const std::string& name)

: customerName(name)

{

std::cout << "Shopping cart created for " << this->customerName << std::endl;

}

// Method chaining

ShoppingCart& addItem(Product* product) {

items.push_back(product);

std::cout << "Added " << product->getName() << " to cart" << std::endl;

return *this; // Enable chaining

}

ShoppingCart& removeItem(Product* product) {

for (auto it = items.begin(); it != items.end(); ++it) {

if (*it == product) {

std::cout << "Removed " << product->getName() << " from cart" << std::endl;

items.erase(it);

break;

}

}

return *this;

}

double calculateTotal() const {

double total = 0;

for (const auto* item : items) {

total += item->getPrice();

}

return total;

}

void displayCart() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Shopping Cart for " << this->customerName << " ===" << std::endl;

if (items.empty()) {

std::cout << "Cart is empty" << std::endl;

return;

}

for (const auto* item : items) {

item->display();

}

std::cout << "Total: $" << calculateTotal() << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Creating Products ===" << std::endl;

Product laptop("Gaming Laptop", 1299.99, 5);

Product mouse("Wireless Mouse", 29.99, 15);

Product keyboard("Mechanical Keyboard", 89.99, 10);

std::cout << "\n=== Method Chaining with Products ===" << std::endl;

// Chain multiple operations on same product

laptop.setPrice(1199.99).applyDiscount(10).adjustStock(-1);

std::cout << "\n=== Product Identity Check ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Is laptop same as itself? "

<< (laptop.isSameProduct(laptop) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

std::cout << "Is laptop same as mouse? "

<< (laptop.isSameProduct(mouse) ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

std::cout << "\n=== Shopping Cart ===" << std::endl;

ShoppingCart cart("Alice Johnson");

// Chain add operations

cart.addItem(&laptop).addItem(&mouse).addItem(&keyboard);

cart.displayCart();

std::cout << "\n=== Removing Item ===" << std::endl;

cart.removeItem(&mouse);

cart.displayCart();

return 0;

}This comprehensive example demonstrates multiple uses of the this pointer working together. The Product class uses this to resolve naming conflicts in setters, enables method chaining by returning asterisk this, and checks object identity using this compared with the address of another object. The ShoppingCart class uses this in the constructor to disambiguate the parameter from the member, and it enables method chaining for adding items. The example shows how these various uses of this combine naturally in well-designed classes to create clear, expressive code.

Understanding when not to use this helps avoid unnecessarily verbose code. In most situations, accessing members directly without explicit this creates cleaner code. Reserve explicit this for situations where it adds clarity or enables specific patterns like resolving naming conflicts, method chaining, passing the current object to functions, or comparing object identity.

Key Takeaways

The this pointer is an implicit parameter automatically passed to every non-static member function that points to the object on which the function was called, enabling member functions to access the specific object’s data and distinguish between different instances of the class. In most code, this works implicitly behind the scenes, and you access member variables directly without typing this, but the compiler translates such accesses to use this automatically.

Explicit use of this becomes necessary or beneficial in several situations. When parameters shadow member variables by having the same names, using this arrow member name disambiguates between the parameter and the member variable. When implementing method chaining where functions return references to enable calling multiple methods in sequence, returning asterisk this provides a reference to the current object. When passing the current object to other functions or registering it with managers, passing this provides the needed pointer or reference. When comparing object identity rather than values, comparing this with the address of another object determines if they are the same object.

In const member functions, this has type const class name asterisk instead of class name asterisk, which prevents modifying member variables and explains why const member functions cannot change object state. Static member functions do not receive a this pointer because they belong to the class rather than to specific instances and cannot access instance members. Understanding the this pointer deeply reveals the mechanism behind member functions and enables writing more sophisticated object-oriented code with patterns like method chaining and self-registration that would otherwise be impossible or clumsy to implement.