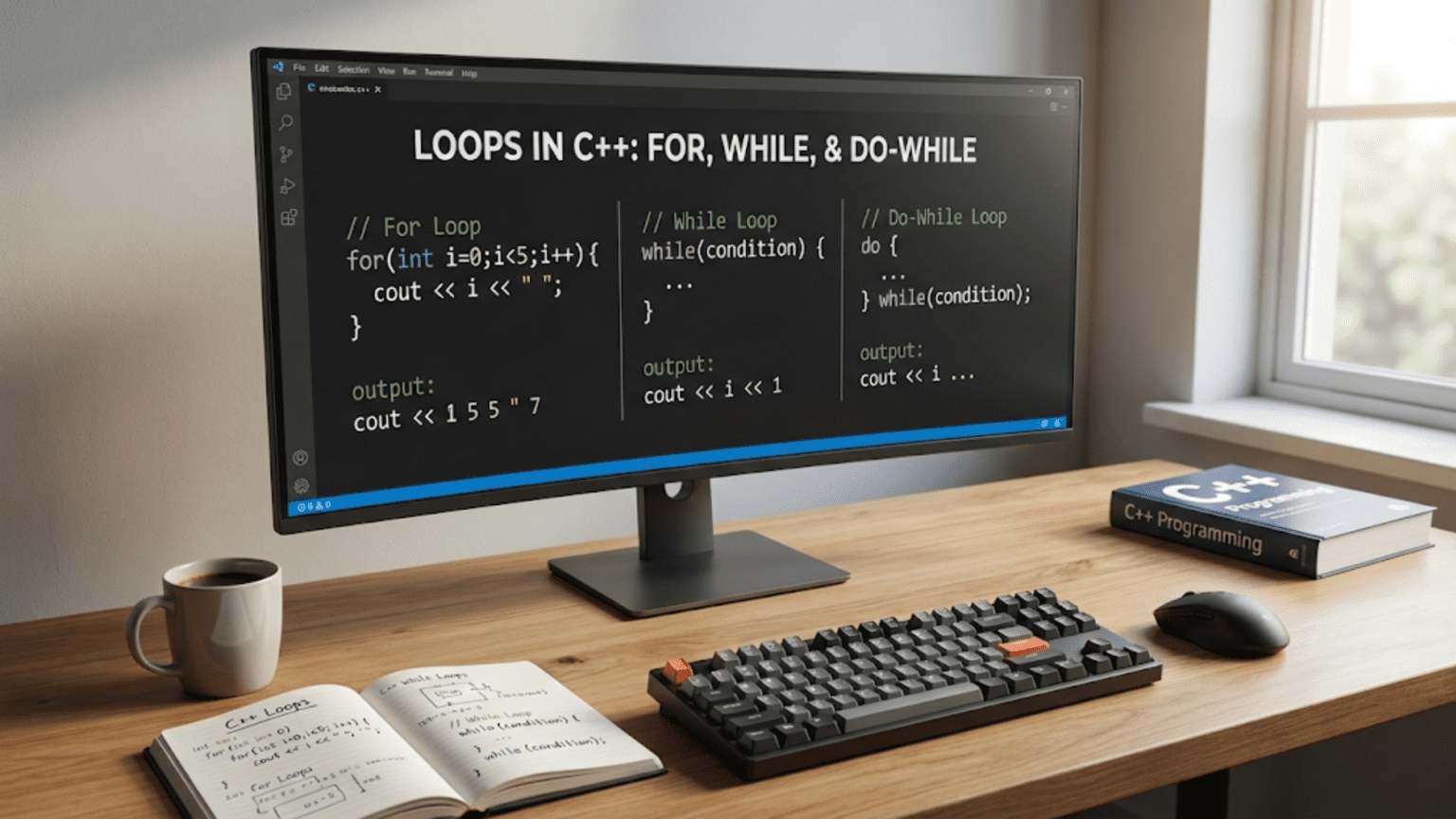

Imagine you need to write a program that displays the numbers from one to one hundred on the screen. You could write one hundred separate output statements, but that would be tedious, error-prone, and completely impractical. What if you then needed to count to one thousand, or one million? Writing individual statements for each number would be impossible. This is where loops come in—they allow your program to repeat actions multiple times without writing the same code over and over again.

Loops represent one of the most powerful concepts in programming because they enable automation of repetitive tasks. Whether you need to process every item in a list, repeat an action until a condition is met, or perform calculations across a range of values, loops provide the mechanism to accomplish these tasks efficiently. Understanding how different types of loops work and when to use each one forms an essential skill for every programmer.

The concept of iteration—repeating a set of instructions multiple times—underpins much of what computers do well. Computers excel at performing the same task thousands or millions of times without getting tired, making mistakes, or complaining. By mastering loops, you harness this computational power to solve problems that would be impossible to tackle manually.

The while loop represents the simplest and most fundamental form of iteration in C++. It continues executing a block of code as long as a specified condition remains true. Think of it as similar to the if statement you learned previously, except instead of executing the code once when the condition is true, the while loop executes it repeatedly until the condition becomes false. The basic syntax follows this pattern:

while (condition) {

// code to execute repeatedly

}Let me show you a concrete example that demonstrates how a while loop works in practice:

int count = 1;

while (count <= 5) {

std::cout << "Count is: " << count << std::endl;

count++;

}

std::cout << "Loop finished!" << std::endl;Let me walk you through exactly what happens when this code executes. The program first creates a variable called count and initializes it to one. Then it encounters the while loop and checks the condition: is count less than or equal to five? Since count currently holds the value one, this condition is true, so the program enters the loop body.

Inside the loop, the program displays the current value of count, which is one. Then the increment operator increases count to two. Now here comes the crucial part that makes loops work: after reaching the closing brace of the loop body, the program doesn’t continue forward to the next line. Instead, it jumps back up to the while statement and checks the condition again. Is count still less than or equal to five? Yes, it’s now two, so the condition remains true.

The program enters the loop body again, displaying two, then incrementing count to three. This cycle repeats—check condition, execute body, increment count, check condition again—until count reaches six. At that point, when the program checks the condition and finds that six is not less than or equal to five, the condition evaluates to false. The loop terminates, and the program continues with the code after the loop, displaying the completion message.

This example illustrates several important principles about while loops. First, the loop variable—count in this case—must be initialized before the loop begins. If you forget to initialize it, you’ll be testing an undefined value, which produces unpredictable behavior. Second, something inside the loop must eventually cause the condition to become false, or the loop will run forever, creating what we call an infinite loop. Third, the condition is checked before each iteration, including the very first one, which means if the condition is false initially, the loop body might never execute at all.

Let me demonstrate that last point with an example:

int value = 10;

while (value < 5) {

std::cout << "This will never print" << std::endl;

value++;

}

std::cout << "Loop skipped entirely" << std::endl;Since value starts at ten, which is not less than five, the condition is false from the very beginning. The loop body never executes even once, and the program proceeds directly to the code after the loop. This behavior makes while loops particularly useful when you’re not certain whether you need to perform an action at all—the condition guards against unnecessary execution.

Understanding infinite loops helps you avoid them and recognize when they occur. An infinite loop happens when the condition never becomes false, causing the loop to run forever:

int count = 1;

while (count <= 5) {

std::cout << "This runs forever!" << std::endl;

// Oops! Forgot to increment count

}Without incrementing count, it remains at one forever, the condition stays true forever, and the loop never terminates. Your program appears to freeze, consuming processor resources while accomplishing nothing. If you accidentally create an infinite loop, you’ll need to forcibly terminate your program—usually by pressing Ctrl+C in the console or stopping execution from your IDE.

Sometimes you want an infinite loop intentionally, particularly in programs that need to keep running until explicitly stopped, like servers or embedded systems:

while (true) {

// Process network requests

// Check sensors

// Update display

// This continues until program is terminated externally

}Using while with the literal value true creates a loop that never terminates on its own. Inside such loops, you would typically include logic that checks for shutdown signals or other conditions that trigger a break statement to exit the loop, which I’ll explain in detail shortly.

Now let me introduce you to the for loop, which packages the three key aspects of iteration—initialization, condition, and update—into a single, compact statement. The for loop is particularly elegant when you know in advance how many times you want to repeat something or when you’re iterating through a specific range of values. The syntax might look complex at first, but it follows a logical structure:

for (initialization; condition; update) {

// code to execute repeatedly

}Here’s how we would write our counting example using a for loop instead of a while loop:

for (int count = 1; count <= 5; count++) {

std::cout << "Count is: " << count << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Loop finished!" << std::endl;Let me break down what happens in this for loop step by step, because understanding the execution flow is crucial. The initialization section—int count equals one—executes exactly once, before the loop begins. This creates the loop variable and sets its starting value. Then the program checks the condition—is count less than or equal to five? Since it is, the program executes the loop body, displaying the message.

After the loop body completes, and this is the part that surprises many beginners, the update expression executes. The count++ statement increments count from one to two. Only after this update does the program check the condition again. This cycle continues—check condition, execute body, perform update, check condition—until the condition becomes false.

Notice how the for loop encapsulates all the loop control logic in one place. The initialization, condition, and update are all visible in the for statement itself, making it clear at a glance what the loop does. Compare this to the while loop version where the initialization happened before the loop and the update happened inside the loop body. The for loop’s concentrated structure reduces the chance of errors like forgetting to update the loop variable.

The for loop shines when iterating through ranges of numbers, which is an extremely common programming task. If you need to process items numbered zero through ninety-nine, a for loop expresses this cleanly:

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

// Process item i

std::cout << "Processing item " << i << std::endl;

}You’ll notice I used a variable name “i” here, which is a convention in programming. For simple counting loops, programmers often use single-letter variable names like i, j, and k. This convention comes from mathematics, where these letters traditionally represent indices. For more complex loops where the variable’s purpose isn’t immediately obvious, using a descriptive name like studentIndex or pageNumber makes your code more readable.

The for loop isn’t limited to incrementing by one. You can count by any amount, count backward, or use more complex update expressions:

// Count by twos

for (int i = 0; i <= 10; i += 2) {

std::cout << i << " "; // Outputs: 0 2 4 6 8 10

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Count backward

for (int i = 5; i >= 1; i--) {

std::cout << i << " "; // Outputs: 5 4 3 2 1

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// More complex progression

for (int i = 1; i <= 100; i *= 2) {

std::cout << i << " "; // Outputs: 1 2 4 8 16 32 64

}

std::cout << std::endl;Each of these loops demonstrates different ways to control iteration. The first counts by twos using the compound assignment operator. The second counts backward using decrement. The third doubles the value each time, creating an exponential progression. The flexibility of the update expression lets you create whatever iteration pattern your problem requires.

You might wonder when to use a for loop versus a while loop. Generally, use a for loop when you know in advance how many iterations you need or when you’re counting through a specific range. Use a while loop when the number of iterations depends on some condition that you can’t predict beforehand. Let me show you an example where a while loop makes more sense:

int userInput;

std::cout << "Enter a number (0 to quit): ";

std::cin >> userInput;

while (userInput != 0) {

std::cout << "You entered: " << userInput << std::endl;

std::cout << "Enter another number (0 to quit): ";

std::cin >> userInput;

}

std::cout << "Goodbye!" << std::endl;In this program, you don’t know how many times the loop will execute—it depends entirely on when the user decides to enter zero. The loop continues as long as the user keeps entering non-zero numbers. This situation calls for a while loop because the termination condition is based on external input rather than counting through a fixed range.

Now let me introduce the do-while loop, which is similar to the while loop but with one crucial difference: it checks the condition after executing the loop body rather than before. This guarantees that the loop body executes at least once, even if the condition is false from the start. The syntax places the while keyword and condition after the loop body:

do {

// code to execute

} while (condition);Notice the semicolon after the condition—this is required for do-while loops and is easy to forget. Here’s a practical example that shows when do-while loops are useful:

int number;

do {

std::cout << "Enter a positive number: ";

std::cin >> number;

if (number <= 0) {

std::cout << "That's not positive. Try again." << std::endl;

}

} while (number <= 0);

std::cout << "Thank you! You entered: " << number << std::endl;This code demonstrates a common pattern: validating user input. You need to ask for input at least once, and if the input is invalid, you need to keep asking until you receive valid input. The do-while loop fits this pattern perfectly because the loop body—which prompts for input and checks validity—must execute at least once, and then continues executing if the validation fails.

Let me show you why a regular while loop would be awkward for this situation:

int number = 0; // Need to initialize to enter loop

while (number <= 0) {

std::cout << "Enter a positive number: ";

std::cin >> number;

if (number <= 0) {

std::cout << "That's not positive. Try again." << std::endl;

}

}The while loop version requires initializing number to zero just to make the condition true so the loop runs the first time. This initialization is artificial—we don’t actually have a number yet; we’re just setting it to zero to trick the loop into running. The do-while loop eliminates this awkwardness by guaranteeing the first execution.

Nested loops—loops inside other loops—allow you to work with multi-dimensional data or perform repeated operations at multiple levels. Each iteration of the outer loop causes the inner loop to execute completely. Let me show you a simple example that creates a multiplication table:

for (int row = 1; row <= 5; row++) {

for (int col = 1; col <= 5; col++) {

std::cout << row * col << "\t"; // \t is tab for spacing

}

std::cout << std::endl; // New line after each row

}Let me walk through how this nested loop executes, because understanding the flow is important. When row equals one, the program enters the inner loop, which runs five complete iterations with col going from one to five. This prints five numbers on one line: one times one, one times two, one times three, one times four, and one times five. After the inner loop completes, the program prints a newline and increments row to two.

Now the outer loop begins its second iteration. The inner loop runs again, this time with row equal to two, printing two times one through two times five. This pattern continues until row exceeds five, at which point the outer loop terminates. The result is a five-by-five grid showing multiplication results.

Nested loops are powerful but come with an important consideration: complexity multiplies. If the outer loop runs ten times and the inner loop runs one hundred times, the total number of inner loop executions is one thousand—ten times one hundred. With multiple levels of nesting, the total iterations can become enormous very quickly. A loop with three levels, each running one hundred times, executes one million times in total. Understanding this helps you recognize when nested loops might cause performance problems.

Loop control statements—break and continue—let you alter the normal flow of loop execution. The break statement immediately terminates the loop, jumping to the code after the loop’s closing brace:

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i == 5) {

break; // Exit loop when i equals 5

}

std::cout << i << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Outputs: 1 2 3 4Even though the loop is supposed to run until i equals ten, the break statement causes it to terminate early when i reaches five. The break statement is useful when you’re searching for something in a loop—once you find what you’re looking for, there’s no point continuing to search, so you break out of the loop:

bool found = false;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

if (data[i] == searchValue) {

std::cout << "Found at position " << i << std::endl;

found = true;

break; // Found it, no need to keep searching

}

}

if (!found) {

std::cout << "Value not found" << std::endl;

}The continue statement works differently—instead of terminating the loop entirely, it skips the rest of the current iteration and moves to the next one:

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

continue; // Skip even numbers

}

std::cout << i << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Outputs: 1 3 5 7 9When i is even, the continue statement executes, causing the program to skip the output statement and jump directly to the next iteration. This effectively filters the output to show only odd numbers. You can often write the same logic without continue by using appropriate conditions, but continue can sometimes make your intent clearer:

// Without continue

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i % 2 != 0) { // Process only odd numbers

std::cout << i << " ";

}

}

// With continue - sometimes more intuitive

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) { // Skip even numbers

continue;

}

std::cout << i << " ";

}In nested loops, break and continue affect only the innermost loop they appear in:

for (int i = 1; i <= 3; i++) {

for (int j = 1; j <= 3; j++) {

if (j == 2) {

break; // Breaks only the inner loop

}

std::cout << "(" << i << "," << j << ") ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

// Outputs:

// (1,1)

// (2,1)

// (3,1)The break statement terminates the inner loop when j equals two, but the outer loop continues normally. If you need to break out of multiple nested loops, you might need a different approach, such as using a boolean flag or restructuring your code.

Common mistakes with loops often involve what programmers call “off-by-one errors”—loops that execute one too many or one too few times. These errors usually stem from confusion about whether to use less-than or less-than-or-equal-to in conditions:

// Want to print numbers 0 through 9 (ten numbers total)

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // Correct: runs 10 times

std::cout << i << " ";

}

for (int i = 0; i <= 10; i++) { // Wrong: runs 11 times!

std::cout << i << " ";

}

// Want to print numbers 1 through 10

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) { // Correct

std::cout << i << " ";

}

for (int i = 1; i < 10; i++) { // Wrong: stops at 9

std::cout << i << " ";

}Paying careful attention to starting values, ending conditions, and whether you’re using inclusive or exclusive bounds prevents these errors. When working with arrays and collections, which you’ll learn about later, the convention in C++ is to start counting at zero and use less-than rather than less-than-or-equal-to, so a loop processing ten items typically uses the condition i less than ten.

Another common mistake involves modifying loop variables in ways that interfere with the loop’s progression:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

std::cout << i << " ";

i += 2; // Don't do this! The for loop already updates i

}This loop increments i twice per iteration—once in the body and once in the for statement’s update expression—causing it to behave unexpectedly. Generally, avoid modifying the loop variable inside the loop body when using a for loop; let the update expression handle it. If you need complex updating logic, a while loop might be more appropriate.

Infinite loops caused by mistakes deserve special attention because they’re frustrating to debug:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i--) { // Wrong: decrementing instead of incrementing!

std::cout << i << " ";

}This loop starts at zero and tries to count down to reach values less than ten, which will never happen—zero is already less than ten, and decrementing makes it more negative, so the condition remains true forever. Always check that your loop’s update moves the variable toward satisfying the exit condition.

Let me show you a practical example that ties together several loop concepts—a program that calculates the sum of numbers entered by the user:

int sum = 0;

int count = 0;

int number;

std::cout << "Enter numbers to sum (enter 0 to finish):" << std::endl;

while (true) { // Infinite loop with break condition inside

std::cin >> number;

if (number == 0) {

break; // Exit loop when user enters 0

}

sum += number;

count++;

}

if (count > 0) {

double average = static_cast<double>(sum) / count;

std::cout << "Sum: " << sum << std::endl;

std::cout << "Count: " << count << std::endl;

std::cout << "Average: " << average << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "No numbers entered." << std::endl;

}This example demonstrates several important patterns. The while true creates an infinite loop that we exit using break when appropriate. This pattern works well when the exit condition is in the middle of the loop rather than at the beginning or end. The program accumulates both the sum and count of numbers, allowing it to calculate an average. The final if statement checks whether any numbers were entered before attempting to calculate the average, preventing division by zero.

Understanding when loops execute zero times, one time, or multiple times helps you design correct loop logic. Think through what happens with boundary cases—what if the user enters zero immediately in the previous example? The loop body never executes, count remains zero, and the program correctly handles this case by displaying the “no numbers entered” message rather than attempting an invalid calculation.

Key Takeaways

Loops enable your programs to perform repetitive tasks efficiently without writing the same code multiple times. The while loop continues executing as long as its condition remains true, checking the condition before each iteration. The for loop packages initialization, condition, and update into a single statement, making it ideal for counting through specific ranges. The do-while loop guarantees at least one execution by checking the condition after the loop body.

Choose the appropriate loop type based on your specific situation. Use for loops when you know in advance how many iterations you need or when counting through a range. Use while loops when the number of iterations depends on conditions that emerge during execution. Use do-while loops when you need to execute the loop body at least once before testing the continuation condition.

Break and continue statements give you fine-grained control over loop execution, allowing you to exit loops early or skip iterations. Nested loops enable working with multi-dimensional data but require careful attention to performance. Watch out for off-by-one errors, infinite loops caused by incorrect update logic, and modifications to loop variables that interfere with expected progression. With practice, you’ll develop intuition for structuring loops correctly and efficiently.