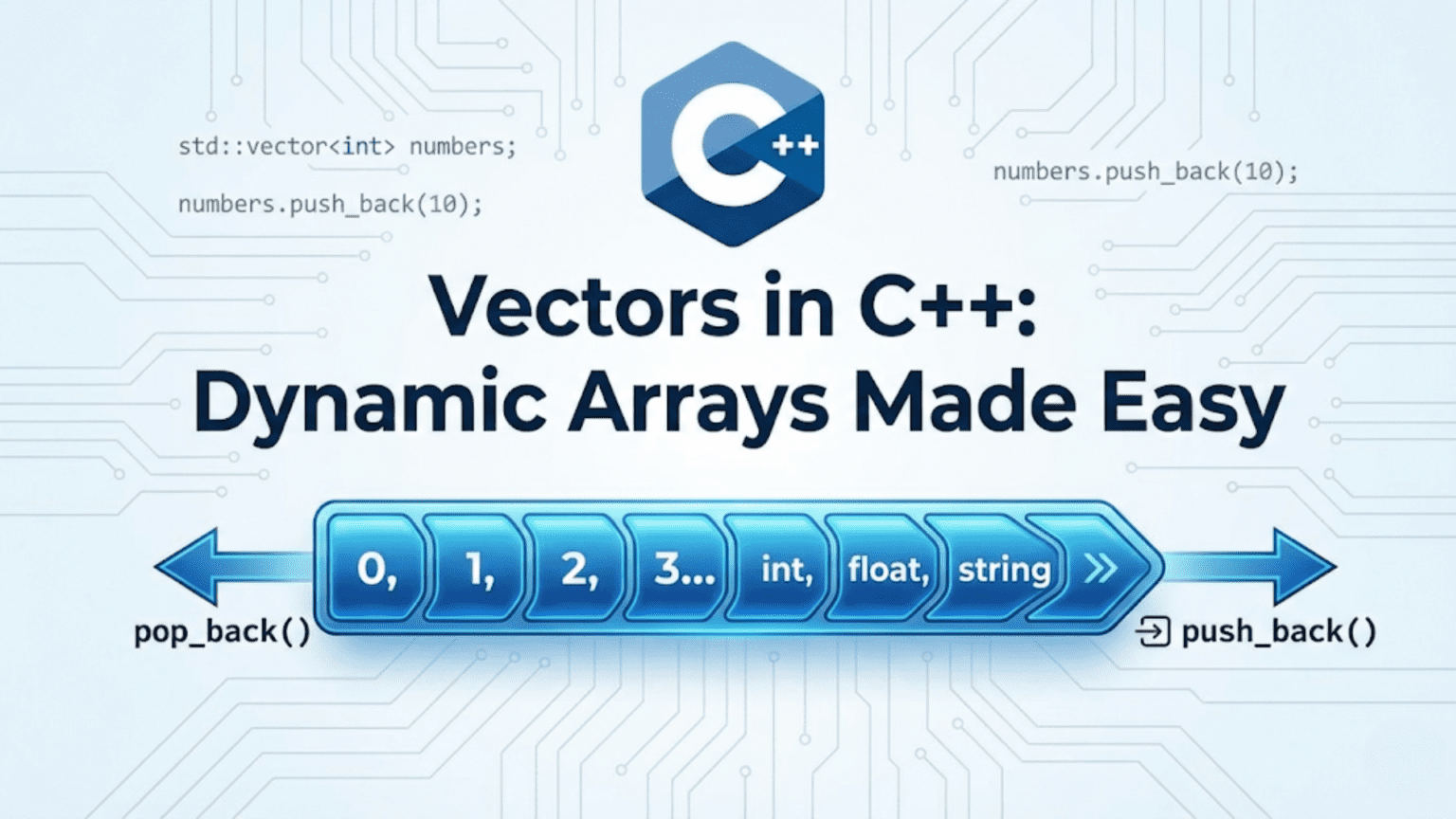

A C++ vector (std::vector) is a dynamic array that automatically resizes itself as elements are added or removed. Unlike plain C-style arrays with fixed sizes, vectors manage their own memory, provide bounds-safe access, support O(1) random access by index, and integrate seamlessly with STL algorithms and iterators—making them the most commonly used container in modern C++ programming.

Introduction: The Array That Grows With You

Every programmer quickly encounters the fundamental limitation of C-style arrays: their size is fixed at compile time. Need to add a 101st element to an array of 100? You’re stuck. You’d have to allocate a bigger array, copy everything over, and manage the old memory yourself—tedious, error-prone work that distracts from solving the actual problem.

std::vector solves this completely. A vector is a sequence container that manages a dynamic array internally, automatically handling memory allocation, resizing, and deallocation. You can push elements onto it indefinitely; the vector grows as needed. When it goes out of scope, it cleans up after itself. This automatic resource management, combined with contiguous memory storage and O(1) random access, makes vector the go-to container for most C++ programming tasks.

In fact, vectors are so fundamental that a common piece of advice in the C++ community is: “When in doubt, use vector.” It offers the best combination of performance (cache-friendly contiguous memory), convenience (auto-resizing, STL integration), and safety (no raw pointer arithmetic) for the vast majority of use cases.

This comprehensive guide will teach you everything about vectors: how to create and initialize them, how to add and remove elements, how to navigate them with iterators, how capacity and size interact, how to avoid common pitfalls, and how to squeeze maximum performance out of them. Every concept is illustrated with practical, step-by-step examples so you understand not just the “what” but the “why.”

Creating and Initializing Vectors

Vectors offer many ways to be constructed and initialized. Choosing the right one makes your code more expressive and efficient.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// 1. Default constructor — empty vector

vector<int> v1;

cout << "v1 (empty): size=" << v1.size() << endl;

// 2. Constructor with initial size

vector<int> v2(5);

cout << "v2 (5 zeros): ";

for (int n : v2) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// 3. Constructor with size and fill value

vector<int> v3(5, 42);

cout << "v3 (5 forties-twos): ";

for (int n : v3) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// 4. Initializer list

vector<int> v4 = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

cout << "v4 (initializer list): ";

for (int n : v4) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// 5. Copy constructor

vector<int> v5 = v4;

cout << "v5 (copy of v4): ";

for (int n : v5) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// 6. From iterator range

vector<int> v6(v4.begin() + 1, v4.end() - 1);

cout << "v6 (middle slice of v4): ";

for (int n : v6) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// 7. Strings vector

vector<string> words = {"hello", "world", "C++"};

cout << "words: ";

for (const string& w : words) cout << w << " ";

cout << endl;

// 8. Vector of vectors (2D)

vector<vector<int>> grid(3, vector<int>(3, 0));

grid[1][1] = 9;

cout << "2D grid [1][1] = " << grid[1][1] << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- vector<int> v1: Default constructor creates an empty vector — size 0, capacity 0

- v1.size(): Returns number of elements currently stored — 0 for empty vector

- vector<int> v2(5): Size constructor — creates 5 elements, each value-initialized to 0

- Value initialization: Integers default to 0, strings to “”, pointers to nullptr

- vector<int> v3(5, 42): Fill constructor — creates 5 elements all set to the value 42

- Initializer list {}: Brace-initialization — most readable for known values at compile time

- vector<int> v5 = v4: Copy constructor — deep copy, v5 is independent of v4

- Range constructor:

vector(begin, end)copies elements from any iterator range - v4.begin() + 1: Points to second element (skips first)

- v4.end() – 1: Points to last element (stops before it)

- Slice result: v6 contains v4’s middle elements {20, 30, 40}

- vector<string>: Works with any type — vector is a template

- vector<vector<int>>: Nested vector creates a 2D structure (grid)

- grid[row][col]: Access 2D grid with double subscript operator

- Inner vector initialization:

vector<int>(3, 0)creates a row of 3 zeros

Output:

v1 (empty): size=0

v2 (5 zeros): 0 0 0 0 0

v3 (5 forties-twos): 42 42 42 42 42

v4 (initializer list): 10 20 30 40 50

v5 (copy of v4): 10 20 30 40 50

v6 (middle slice of v4): 20 30 40

words: hello world C++

2D grid [1][1] = 9Adding and Inserting Elements

Vectors provide multiple ways to add elements, each with different performance characteristics.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v;

// --- push_back: add to end ---

cout << "=== push_back ===" << endl;

v.push_back(10);

v.push_back(20);

v.push_back(30);

cout << "After push_back 10, 20, 30: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- emplace_back: construct in-place at end (more efficient) ---

cout << "\n=== emplace_back ===" << endl;

v.emplace_back(40); // Constructs 40 directly — no temporary copy

v.emplace_back(50);

cout << "After emplace_back 40, 50: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- insert at specific position ---

cout << "\n=== insert ===" << endl;

auto it = v.begin() + 2; // Iterator to index 2

v.insert(it, 99); // Insert 99 before index 2

cout << "After inserting 99 at index 2: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- insert multiple copies ---

v.insert(v.begin(), 3, 0); // Insert 3 zeros at beginning

cout << "After inserting 3 zeros at start: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- insert a range ---

vector<int> extra = {100, 200, 300};

v.insert(v.end(), extra.begin(), extra.end());

cout << "After inserting range {100,200,300} at end: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- assign: replace entire contents ---

cout << "\n=== assign ===" << endl;

v.assign(4, 7); // Replace with 4 sevens

cout << "After assign(4, 7): ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

v.assign({1, 2, 3, 4, 5}); // Assign from initializer list

cout << "After assign({1,2,3,4,5}): ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- push_back(10): Appends 10 to the end of the vector — O(1) amortized

- Amortized O(1): Occasionally triggers a resize (O(n)) but on average each push_back is O(1)

- Three push_backs: Vector now holds {10, 20, 30}

- emplace_back(40): Constructs element directly in the vector’s memory — avoids temporary copy

- When emplace_back wins: For complex objects, emplace_back passes constructor args directly

- For ints: push_back and emplace_back are equivalent — difference matters for objects

- v.begin() + 2: Random-access iterator arithmetic, points to index 2 (value 30)

- insert(it, 99): Inserts 99 before the element at iterator position — O(n) due to shifting

- Elements shift right: All elements from index 2 onward move one position right

- insert(v.begin(), 3, 0): Inserts 3 copies of value 0 at the beginning

- Range insert:

insert(pos, first, last)copies all elements from [first, last) at pos - assign(4, 7): Destroys all existing elements and fills with 4 sevens

- assign from initializer list: Replaces contents with the listed values

- Iterator invalidation warning: After insert or assign, all previously held iterators become invalid

Output:

=== push_back ===

After push_back 10, 20, 30: 10 20 30

=== emplace_back ===

After emplace_back 40, 50: 10 20 30 40 50

=== insert ===

After inserting 99 at index 2: 10 20 99 30 40 50

After inserting 3 zeros at start: 0 0 0 10 20 99 30 40 50

After inserting range {100,200,300} at end: 0 0 0 10 20 99 30 40 50 100 200 300

=== assign ===

After assign(4, 7): 7 7 7 7

After assign({1,2,3,4,5}): 1 2 3 4 5Accessing Elements

Vectors provide multiple safe and unsafe access methods. Knowing which to use is essential.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// --- Subscript operator [] (no bounds checking) ---

cout << "=== Subscript operator [] ===" << endl;

cout << "v[0] = " << v[0] << endl;

cout << "v[2] = " << v[2] << endl;

cout << "v[4] = " << v[4] << endl;

// v[10] = 99; // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR — no bounds check, no exception

// --- at() method (with bounds checking) ---

cout << "\n=== at() method (safe) ===" << endl;

cout << "v.at(0) = " << v.at(0) << endl;

cout << "v.at(3) = " << v.at(3) << endl;

try {

cout << "v.at(10) = " << v.at(10) << endl; // Out of bounds

} catch (const out_of_range& e) {

cout << "Exception caught: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- front() and back() ---

cout << "\n=== front() and back() ===" << endl;

cout << "Front: " << v.front() << endl;

cout << "Back: " << v.back() << endl;

// --- data() — raw pointer to underlying array ---

cout << "\n=== data() — raw pointer ===" << endl;

int* raw = v.data();

cout << "First via raw pointer: " << raw[0] << endl;

cout << "Third via raw pointer: " << raw[2] << endl;

// Useful when interfacing with C APIs expecting int*

// --- Modifying via access ---

cout << "\n=== Modifying elements ===" << endl;

v[0] = 100;

v.at(4) = 500;

v.front() = 999;

cout << "After modifications: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- Access on const vector ---

cout << "\n=== Const vector access ===" << endl;

const vector<int> cv = {1, 2, 3};

cout << "cv[1] = " << cv[1] << endl;

cout << "cv.at(2) = " << cv.at(2) << endl;

// cv[0] = 99; // ERROR: cannot assign to const

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- v[0]: Subscript operator — O(1) access, no bounds checking

- Fast but unsafe: If index >= size, behavior is undefined (crash or garbage)

- v[2]: Returns reference to element at index 2 — can be used as lvalue

- v.at(0): Bounds-checked access — throws std::out_of_range if index invalid

- at() is safer: Prefer at() during development/debugging for safety

- try-catch block: Catches the out_of_range exception thrown by v.at(10)

- e.what(): Returns a descriptive error message string

- v.front(): Returns reference to the first element — equivalent to v[0]

- v.back(): Returns reference to the last element — equivalent to v[v.size()-1]

- v.data(): Returns raw pointer to the underlying array — enables C interoperability

- raw[0]: Pointer arithmetic access, identical to v[0]

- C API use case: Many C functions require

int*— data() provides it - v[0] = 100: Subscript operator returns lvalue reference — supports assignment

- v.front() = 999: front() also returns lvalue reference — modifiable

- const vector<int> cv: Read-only vector — subscript and at() work, but no modification

Output:

=== Subscript operator [] ===

v[0] = 10

v[2] = 30

v[4] = 50

=== at() method (safe) ===

v.at(0) = 10

v.at(3) = 40

Exception caught: vector::_M_range_check: __n (which is 10) >= this->size() (which is 5)

=== front() and back() ===

Front: 10

Back: 50

=== data() — raw pointer ===

First via raw pointer: 10

Third via raw pointer: 30

=== Modifying elements ===

After modifications: 999 20 30 40 500

=== Const vector access ===

cv[1] = 2

cv.at(2) = 3Removing Elements

Vectors support several removal strategies, each with different complexity.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

void print(const vector<int>& v, const string& label) {

cout << label << ": ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << "(size=" << v.size() << ")" << endl;

}

int main() {

// --- pop_back: remove last element ---

cout << "=== pop_back ===" << endl;

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

print(v, "Before");

v.pop_back();

print(v, "After pop_back");

// --- erase single element by iterator ---

cout << "\n=== erase (single element) ===" << endl;

v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

print(v, "Before");

v.erase(v.begin() + 2); // Remove element at index 2 (value 30)

print(v, "After erase index 2");

// --- erase range ---

cout << "\n=== erase (range) ===" << endl;

v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

print(v, "Before");

v.erase(v.begin() + 1, v.begin() + 4); // Remove indices 1, 2, 3

print(v, "After erase [1,4)");

// --- clear: remove all elements ---

cout << "\n=== clear ===" << endl;

v = {10, 20, 30};

print(v, "Before");

v.clear();

print(v, "After clear");

cout << "Capacity after clear: " << v.capacity() << endl; // Capacity unchanged!

// --- Erase-remove idiom: remove by value ---

cout << "\n=== Erase-Remove Idiom ===" << endl;

v = {1, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 5};

print(v, "Before");

v.erase(remove(v.begin(), v.end(), 2), v.end());

print(v, "After removing all 2s");

// --- Erase-remove with predicate ---

cout << "\n=== Erase-Remove with Predicate ===" << endl;

v = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10};

print(v, "Before");

v.erase(

remove_if(v.begin(), v.end(), [](int n){ return n % 2 == 0; }),

v.end()

);

print(v, "After removing all even numbers");

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- pop_back(): Removes the last element — O(1), no shifting required

- pop_back does not return: Unlike stack’s pop, vector’s pop_back returns void — read back() first

- erase(iterator): Removes element at the iterator position — O(n) due to left-shift

- v.begin() + 2: Points to element at index 2 (value 30)

- Elements shift left: After erasing index 2, former index 3 becomes index 2

- erase(first, last): Removes range [first, last) — half-open interval

- Erasing [1,4): Removes elements at indices 1, 2, and 3 — three elements removed

- clear(): Sets size to 0, removes all elements — O(n) (destructors called)

- Capacity unchanged: clear() does NOT release memory — capacity stays allocated

- remove(begin, end, 2): Moves all non-2 elements to the front, returns new logical end

- remove doesn’t erase: It rearranges elements — actual erasure requires erase()

- Erase-remove idiom: The two-step remove() + erase() pattern is idiomatic C++

- remove_if(begin, end, pred): Moves elements not matching predicate to front

- Lambda predicate:

[](int n){ return n % 2 == 0; }returns true for even numbers - Combined operation: remove_if + erase efficiently removes all matching elements

Output:

=== pop_back ===

Before: 10 20 30 40 50 (size=5)

After pop_back: 10 20 30 40 (size=4)

=== erase (single element) ===

Before: 10 20 30 40 50 (size=5)

After erase index 2: 10 20 40 50 (size=4)

=== erase (range) ===

Before: 10 20 30 40 50 (size=5)

After erase [1,4): 10 50 (size=2)

=== clear ===

Before: 10 20 30 (size=3)

After clear: (size=0)

Capacity after clear: 3

=== Erase-Remove Idiom ===

Before: 1 2 3 2 4 2 5 (size=7)

After removing all 2s: 1 3 4 5 (size=4)

=== Erase-Remove with Predicate ===

Before: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (size=10)

After removing all even numbers: 1 3 5 7 9 (size=5)Size vs Capacity: Understanding Vector Growth

Understanding the relationship between size and capacity is key to writing efficient vector code.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v;

cout << "=== Watching size and capacity grow ===" << endl;

cout << "Initial — size: " << v.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v.capacity() << endl;

for (int i = 1; i <= 16; i++) {

v.push_back(i);

cout << "After push_back(" << i << ") — size: " << v.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v.capacity() << endl;

}

// --- reserve: pre-allocate capacity ---

cout << "\n=== reserve: pre-allocate capacity ===" << endl;

vector<int> v2;

v2.reserve(100); // Allocate space for 100 elements

cout << "After reserve(100) — size: " << v2.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v2.capacity() << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) v2.push_back(i);

cout << "After 10 push_backs — size: " << v2.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v2.capacity() << endl; // Still 100

// --- resize: change size ---

cout << "\n=== resize ===" << endl;

vector<int> v3 = {1, 2, 3};

cout << "Before resize(6) — size: " << v3.size() << endl;

v3.resize(6); // Grow — new elements value-initialized to 0

cout << "After resize(6): ";

for (int n : v3) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

v3.resize(2); // Shrink — removes elements beyond index 2

cout << "After resize(2): ";

for (int n : v3) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- shrink_to_fit: release excess capacity ---

cout << "\n=== shrink_to_fit ===" << endl;

vector<int> v4;

v4.reserve(1000);

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) v4.push_back(i);

cout << "Before shrink — size: " << v4.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v4.capacity() << endl;

v4.shrink_to_fit();

cout << "After shrink_to_fit — size: " << v4.size()

<< ", capacity: " << v4.capacity() << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Initial state: Empty vector — size 0, capacity 0 (no allocation yet)

- First push_back: Triggers first allocation, typically capacity becomes 1

- Doubling strategy: Most implementations double capacity when full (1→2→4→8→16→…)

- Doubling amortizes cost: Reallocation happens infrequently — total cost is O(n)

- Size vs capacity: Size = actual elements; capacity = allocated memory (always >= size)

- Reallocation copies: When capacity exceeded, new larger array allocated, all elements copied

- reserve(100): Allocates memory for 100 elements — no elements added, size stays 0

- Benefit of reserve: Prevents reallocations when you know max size in advance

- Capacity stays 100: push_backs don’t trigger reallocation while size < capacity

- resize(6): Grows size to 6, new elements default-initialized (0 for int)

- resize(2): Shrinks size to 2 — elements beyond index 2 are destroyed

- Capacity may remain: resize() does not reduce capacity

- shrink_to_fit(): Requests capacity be reduced to match size (non-binding hint)

- Memory release: After shrink_to_fit(), capacity should equal size

- When to use reserve(): Whenever you know approximate final size — avoids O(n log n) reallocations

Output (capacity doubling pattern may vary by implementation):

=== Watching size and capacity grow ===

Initial — size: 0, capacity: 0

After push_back(1) — size: 1, capacity: 1

After push_back(2) — size: 2, capacity: 2

After push_back(3) — size: 3, capacity: 4

After push_back(4) — size: 4, capacity: 4

After push_back(5) — size: 5, capacity: 8

After push_back(6) — size: 6, capacity: 8

After push_back(7) — size: 7, capacity: 8

After push_back(8) — size: 8, capacity: 8

After push_back(9) — size: 9, capacity: 16

After push_back(10) — size: 10, capacity: 16

After push_back(11) — size: 11, capacity: 16

After push_back(12) — size: 12, capacity: 16

After push_back(13) — size: 13, capacity: 16

After push_back(14) — size: 14, capacity: 16

After push_back(15) — size: 15, capacity: 16

After push_back(16) — size: 16, capacity: 16

=== reserve: pre-allocate capacity ===

After reserve(100) — size: 0, capacity: 100

After 10 push_backs — size: 10, capacity: 100

=== resize ===

Before resize(6) — size: 3

After resize(6): 1 2 3 0 0 0

After resize(2): 1 2

=== shrink_to_fit ===

Before shrink — size: 5, capacity: 1000

After shrink_to_fit — size: 5, capacity: 5Iterating Over Vectors

Vectors support several iteration styles—choosing the right one improves clarity and safety.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// --- Style 1: Index-based (classic) ---

cout << "=== Index-based loop ===" << endl;

for (size_t i = 0; i < v.size(); i++) {

cout << "v[" << i << "] = " << v[i] << endl;

}

// --- Style 2: Range-based for (modern, preferred) ---

cout << "\n=== Range-based for loop ===" << endl;

for (int n : v) {

cout << n << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Style 3: Range-based with const reference (efficient for objects) ---

cout << "\n=== Range-based with const reference ===" << endl;

for (const int& n : v) {

cout << n << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Style 4: Iterator-based ---

cout << "\n=== Iterator-based loop ===" << endl;

for (auto it = v.begin(); it != v.end(); ++it) {

cout << *it << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Style 5: Reverse iteration ---

cout << "\n=== Reverse iteration ===" << endl;

for (auto rit = v.rbegin(); rit != v.rend(); ++rit) {

cout << *rit << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Style 6: for_each algorithm ---

cout << "\n=== for_each with lambda ===" << endl;

for_each(v.begin(), v.end(), [](int n) {

cout << n * n << " "; // Print square

});

cout << endl;

// --- Modifying during iteration ---

cout << "\n=== Modifying via range-based for ===" << endl;

for (int& n : v) { // Note: reference, not copy

n += 5;

}

cout << "After adding 5 to each: ";

for (int n : v) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Index-based loop: Classic C style — use when you need the index value

- size_t: Unsigned integer type returned by size() — avoids signed/unsigned comparison warning

- Range-based for: Cleanest syntax — recommended default for read-only iteration

for (int n : v): Copies each element — fine for primitives, expensive for large objectsfor (const int& n : v): Reference to element — no copy, read-only (const)- When to use const ref: For objects (strings, structs) to avoid unnecessary copies

- Iterator-based: Most verbose but most flexible — needed for insert/erase during loop

- auto it: Type deduction avoids spelling out

vector<int>::iterator - it != v.end(): Idiomatic iterator loop condition — not < comparison

- v.rbegin() / v.rend(): Reverse iterators — traverse from back to front

- for_each: Algorithm-based iteration — accepts any callable including lambdas

- Lambda

[](int n){}: Inline function applied to each element for (int& n : v): Non-const reference — modifications propagate to the vector- Avoid modifying while iterating with erase: Can invalidate iterators — use erase-remove idiom instead

Output:

=== Index-based loop ===

v[0] = 10

v[1] = 20

v[2] = 30

v[3] = 40

v[4] = 50

=== Range-based for loop ===

10 20 30 40 50

=== Range-based with const reference ===

10 20 30 40 50

=== Iterator-based loop ===

10 20 30 40 50

=== Reverse iteration ===

50 40 30 20 10

=== for_each with lambda ===

100 400 900 1600 2500

=== Modifying via range-based for ===

After adding 5 to each: 15 25 35 45 55Vectors with Custom Objects

Vectors work with any type—including your own classes. Here’s how to use them with custom objects.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

struct Student {

string name;

int grade;

Student(string n, int g) : name(n), grade(g) {}

void display() const {

cout << name << " (grade: " << grade << ")";

}

};

int main() {

// --- Vector of objects ---

cout << "=== Vector of Students ===" << endl;

vector<Student> students;

students.emplace_back("Alice", 92); // Construct in-place

students.emplace_back("Bob", 78);

students.emplace_back("Charlie", 85);

students.emplace_back("Diana", 95);

students.emplace_back("Eve", 88);

cout << "All students:" << endl;

for (const Student& s : students) {

cout << " ";

s.display();

cout << endl;

}

// --- Sort by grade descending ---

cout << "\n=== Sorted by grade (highest first) ===" << endl;

sort(students.begin(), students.end(), [](const Student& a, const Student& b) {

return a.grade > b.grade;

});

for (const Student& s : students) {

cout << " ";

s.display();

cout << endl;

}

// --- Find specific student ---

cout << "\n=== Finding Charlie ===" << endl;

auto it = find_if(students.begin(), students.end(), [](const Student& s) {

return s.name == "Charlie";

});

if (it != students.end()) {

cout << "Found: ";

it->display();

cout << endl;

}

// --- Filter: students with grade >= 90 ---

cout << "\n=== Top students (grade >= 90) ===" << endl;

vector<Student> topStudents;

copy_if(students.begin(), students.end(), back_inserter(topStudents),

[](const Student& s) { return s.grade >= 90; });

for (const Student& s : topStudents) {

cout << " ";

s.display();

cout << endl;

}

// --- Compute average grade ---

cout << "\n=== Average grade ===" << endl;

double total = 0;

for (const Student& s : students) total += s.grade;

double average = total / students.size();

cout << "Average grade: " << average << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- struct Student: Simple aggregate type with name and grade

- Constructor: Initializes name and grade via member initializer list

- vector<Student>: Specializes vector template for Student type

- emplace_back(“Alice”, 92): Constructs Student directly in vector — passes args to constructor

- emplace_back vs push_back: emplace_back avoids creating a temporary Student object

- const Student& s: Read-only reference in range-for — efficient for objects

- s.display(): Calls member function through reference

- sort with lambda: Custom comparator sorts by grade descending

- a.grade > b.grade: Returns true when a should come before b — highest grade first

- find_if(): Searches for first element matching predicate

- Lambda predicate:

s.name == "Charlie"— string comparison as search criterion - it->display(): Arrow operator on iterator — equivalent to

(*it).display() - copy_if(): Copies elements matching predicate to output range

- back_inserter: Grows topStudents as each matching element is copied

- Total accumulation: Manual for-loop computes sum, then divides by size()

Output:

=== Vector of Students ===

All students:

Alice (grade: 92)

Bob (grade: 78)

Charlie (grade: 85)

Diana (grade: 95)

Eve (grade: 88)

=== Sorted by grade (highest first) ===

Diana (grade: 95)

Alice (grade: 92)

Eve (grade: 88)

Charlie (grade: 85)

Bob (grade: 78)

=== Finding Charlie ===

Found: Charlie (grade: 85)

=== Top students (grade >= 90) ===

Diana (grade: 95)

Alice (grade: 92)

=== Average grade ===-

Average grade: 87.6Common Vector Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// PITFALL 1: Iterator invalidation after push_back

cout << "=== Pitfall 1: Iterator Invalidation ===" << endl;

vector<int> v = {1, 2, 3};

// auto it = v.begin(); // Saved iterator

// v.push_back(4); // May trigger reallocation!

// cout << *it; // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR — it may be dangling

cout << "Solution: Don't save iterators across push_back calls." << endl;

cout << "Or call reserve() first to prevent reallocation." << endl;

// PITFALL 2: Out-of-bounds with []

cout << "\n=== Pitfall 2: Unchecked Access ===" << endl;

vector<int> v2 = {10, 20, 30};

// cout << v2[5]; // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR — no exception, random data

cout << "Solution: Use v.at(5) during development — throws out_of_range." << endl;

// PITFALL 3: Inefficient push_back in loop (no reserve)

cout << "\n=== Pitfall 3: No Reserve Before Loop ===" << endl;

const int N = 1000000;

vector<int> bad;

// for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) bad.push_back(i); // Multiple reallocations

vector<int> good;

good.reserve(N); // One allocation

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) good.push_back(i); // No reallocations

cout << "Reserved vector — capacity: " << good.capacity() << endl;

// PITFALL 4: Erasing during loop

cout << "\n=== Pitfall 4: Erasing During Iteration ===" << endl;

vector<int> v3 = {1, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 5};

// WRONG — skips elements

// for (auto it = v3.begin(); it != v3.end(); ++it) {

// if (*it == 2) v3.erase(it); // it now invalid!

// }

// CORRECT — erase returns valid next iterator

for (auto it = v3.begin(); it != v3.end(); ) {

if (*it == 2) {

it = v3.erase(it); // erase returns iterator to next element

} else {

++it;

}

}

cout << "After safe erase of 2s: ";

for (int n : v3) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// PITFALL 5: Copying when move is intended

cout << "\n=== Pitfall 5: Unnecessary Copies ===" << endl;

vector<int> source = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

vector<int> moved = move(source); // Move — O(1), source is now empty

cout << "Moved vector size: " << moved.size() << endl;

cout << "Source after move: size=" << source.size() << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Iterator invalidation: push_back may trigger reallocation, moving all data to new memory

- Dangling iterator: Old iterator points to freed memory after reallocation

- Solution: Use reserve() before push_back loop, or don’t save iterators across mutations

- Unchecked []: v[5] on a 3-element vector accesses arbitrary memory — no error thrown

- at() for safety: Bounds-checked access throws std::out_of_range — use during development

- No reserve anti-pattern: Each push_back may trigger O(n) reallocation — total O(n log n)

- With reserve(): One O(n) allocation upfront, then O(1) push_backs — total O(n)

- Erasing during loop: erase() invalidates the iterator, and ++it would skip or crash

- erase() return value: Returns iterator to the element that replaced the erased one

- Safe pattern:

it = v.erase(it)reuses the returned valid iterator - Else branch: Only advance iterator if no erasure happened — avoids skipping elements

- std::move(): Transfers ownership of internal buffer — O(1) operation

- Source emptied: After move, source vector is valid but empty (size=0)

- When to move: Moving instead of copying large vectors is a major performance win

Output:

=== Pitfall 1: Iterator Invalidation ===

Solution: Don't save iterators across push_back calls.

Or call reserve() first to prevent reallocation.

=== Pitfall 2: Unchecked Access ===

Solution: Use v.at(5) during development — throws out_of_range.

=== Pitfall 3: No Reserve Before Loop ===

Reserved vector — capacity: 1000000

=== Pitfall 4: Erasing During Iteration ===

After safe erase of 2s: 1 3 4 5

=== Pitfall 5: Unnecessary Copies ===

Moved vector size: 5

Source after move: size=0Vector Quick Reference

| Operation | Method | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Access by index | v[i], v.at(i) | O(1) |

| First / last element | v.front(), v.back() | O(1) |

| Add to end | push_back(), emplace_back() | O(1) amortized |

| Remove from end | pop_back() | O(1) |

| Insert at position | insert(it, val) | O(n) |

| Remove at position | erase(it) | O(n) |

| Remove all | clear() | O(n) |

| Number of elements | size() | O(1) |

| Allocated capacity | capacity() | O(1) |

| Pre-allocate | reserve(n) | O(n) |

| Change size | resize(n) | O(n) |

| Release excess | shrink_to_fit() | O(n) |

| Empty check | empty() | O(1) |

Conclusion: Vectors as Your Default Container

The C++ vector is the workhorse of the STL—flexible, efficient, and safe. Its combination of O(1) random access, automatic resizing, and seamless integration with STL algorithms makes it the right choice for the majority of data storage needs in C++.

Key takeaways:

- Prefer vector over raw arrays for almost all dynamic collections

- Use

emplace_back()overpush_back()when constructing objects in-place - Use

at()during development for bounds checking; switch to[]for performance-critical paths - Always call

reserve()before a push_back loop when you know the final size - Use the erase-remove idiom (

remove()+erase()) to delete elements by value or predicate - Understand size vs capacity — they serve different purposes

- Iterator invalidation happens after any reallocation-triggering operation — don’t store iterators across mutations

- Prefer range-based for loops with

const T&for read-only iteration of objects - Use

std::move()when transferring ownership to avoid expensive copies

Once you master vectors, you have a solid foundation for understanding the rest of the STL. The patterns you learn here—iterator-based algorithms, lambdas as predicates, erase-remove idiom, reserve for performance—apply throughout the entire library. Make vector your default container, and you’ll write cleaner, safer, and more efficient C++ from day one.