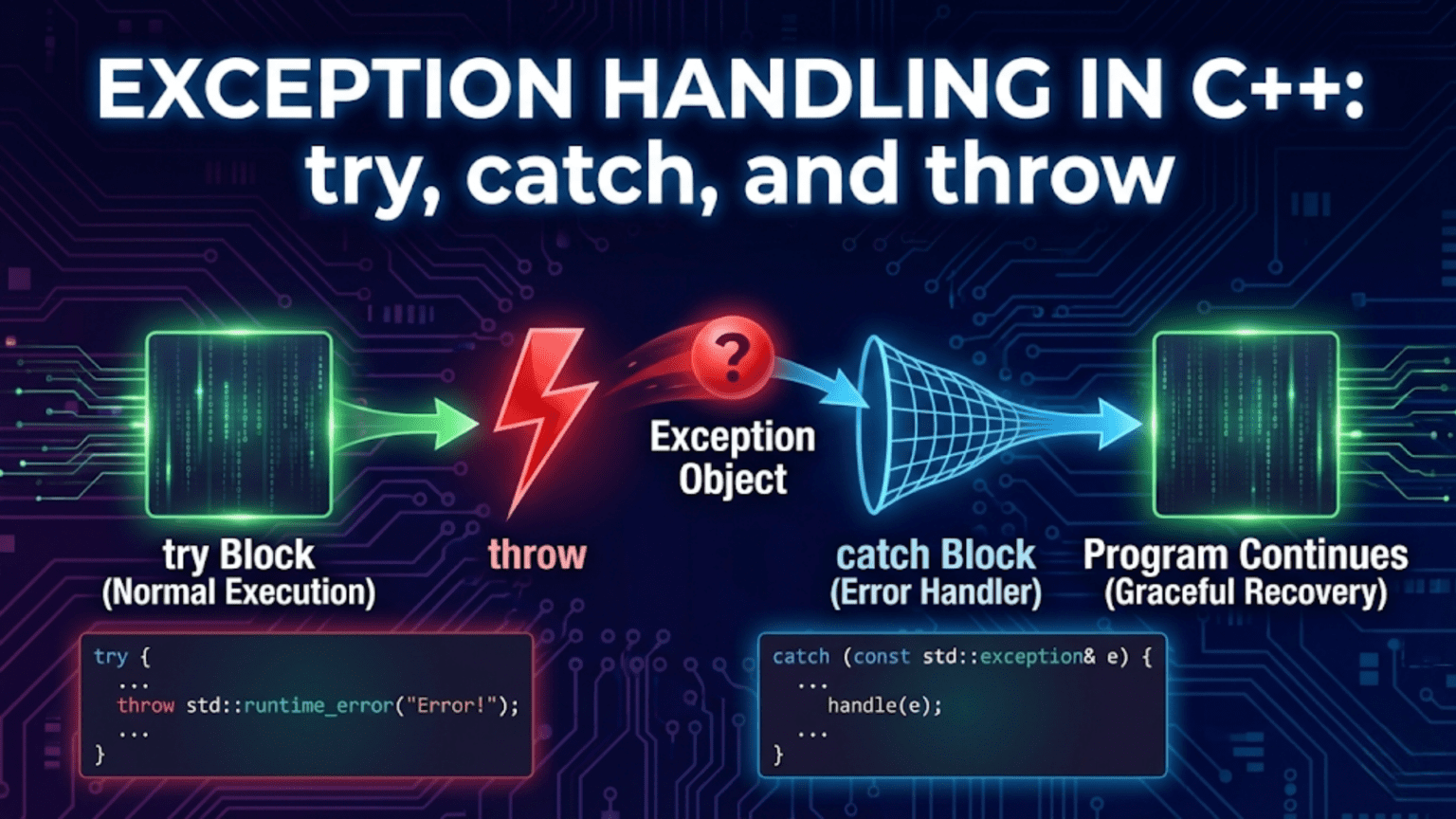

C++ exception handling uses three keywords—try, catch, and throw—to detect and respond to runtime errors. Code that might fail is placed in a try block; when an error occurs, throw creates an exception object and transfers control to the nearest matching catch block, bypassing normal execution flow. This mechanism separates error-handling code from normal logic, enables errors to propagate up the call stack automatically, and integrates with RAII to guarantee resource cleanup even when exceptions occur.

Introduction: Why Exception Handling Matters

Every program faces situations it didn’t plan for: a file that doesn’t exist, a network connection that drops, memory that can’t be allocated, invalid user input, a division by zero. How a program handles these unexpected situations determines whether it crashes, silently corrupts data, or fails gracefully with useful feedback.

Before exception handling, C programmers used error codes—functions returned special values indicating failure, and callers had to check every return value. This approach is tedious, easy to forget, and clutters business logic with error-checking code. It also doesn’t work for constructors, which have no return value.

C++ exception handling offers a fundamentally different model. Errors are thrown as exception objects that automatically propagate up the call stack until something catches them. The normal code path stays clean and readable. Error-handling code lives in catch blocks, clearly separated from the happy path. And crucially, the stack unwinding process that occurs during exception propagation ensures that destructors run—which, combined with RAII, guarantees resources are always released properly.

This comprehensive guide teaches you everything about C++ exception handling: the basic try-catch-throw mechanism, standard exception types, custom exception classes, catching by reference, exception hierarchies, stack unwinding, RAII for exception safety, noexcept, and best practices. Every concept is illustrated with practical, step-by-step examples.

Basic try, catch, and throw

The three keywords form the core of C++ exception handling.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

double divide(double a, double b) {

if (b == 0.0) {

throw runtime_error("Division by zero is not allowed");

}

return a / b;

}

int main() {

// --- Basic try-catch ---

cout << "=== Basic try-catch ===" << endl;

try {

double result = divide(10.0, 2.0);

cout << "10 / 2 = " << result << endl;

result = divide(5.0, 0.0); // This throws

cout << "This line never executes" << endl;

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "Caught exception: " << e.what() << endl;

}

cout << "Program continues after catch block" << endl;

// --- Multiple try-catch blocks ---

cout << "\n=== Multiple exceptions ===" << endl;

for (double denominator : {3.0, 0.0, -1.0}) {

try {

double result = divide(12.0, denominator);

cout << "12 / " << denominator << " = " << result << endl;

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "Error for denominator " << denominator

<< ": " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

cout << "\nAll iterations completed" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- throw runtime_error(“…”): Creates a runtime_error object and throws it — immediately exits the function

- No return after throw: Execution jumps to the nearest matching catch block — code below throw never runs

- try block: Contains code that might throw — execution is “watched” for exceptions

- catch (const runtime_error& e): Catches runtime_error exceptions —

eprovides access to the exception - e.what(): Member function returning the error message string — defined in std::exception

- Catch by const reference: Avoids copying the exception object — more efficient, standard practice

- “This line never executes”: When divide throws, control jumps to catch — skips remaining try-block code

- Program continues after catch: After catch runs, execution resumes AFTER the try-catch block

- Loop with try-catch: Each iteration has its own try-catch — exception in one doesn’t stop others

- Denominator 0.0: Triggers the throw — caught by catch block

- Other denominators: No exception — try block completes normally, catch block skipped

- Exception vs error code: No manual return-value checking — exception propagates automatically

- Separation of concerns: divide() only has division logic — error-handling lives in caller

- Scope: After catch block, the exception object

egoes out of scope and is destroyed

Output:

=== Basic try-catch ===

10 / 2 = 5

Caught exception: Division by zero is not allowed

Program continues after catch block

=== Multiple exceptions ===

12 / 3 = 4

Error for denominator 0: Division by zero is not allowed

12 / -1 = -12

All iterations completedStandard Exception Types

C++ provides a rich hierarchy of standard exceptions in <stdexcept> and other headers.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

void demonstrateStandardExceptions() {

// --- runtime_error: errors detectable only at runtime ---

cout << "=== runtime_error ===" << endl;

try {

throw runtime_error("Something went wrong at runtime");

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "runtime_error: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- range_error: mathematical range violation ---

cout << "\n=== range_error ===" << endl;

try {

throw range_error("Result outside valid range");

}

catch (const range_error& e) {

cout << "range_error: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- overflow_error ---

cout << "\n=== overflow_error ===" << endl;

try {

throw overflow_error("Arithmetic overflow occurred");

}

catch (const overflow_error& e) {

cout << "overflow_error: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- logic_error: violations of logical preconditions ---

cout << "\n=== logic_error ===" << endl;

try {

throw logic_error("Function called with invalid arguments");

}

catch (const logic_error& e) {

cout << "logic_error: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- invalid_argument ---

cout << "\n=== invalid_argument ===" << endl;

try {

throw invalid_argument("Argument must be positive");

}

catch (const invalid_argument& e) {

cout << "invalid_argument: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- out_of_range: from STL containers ---

cout << "\n=== out_of_range (from vector::at) ===" << endl;

try {

vector<int> v = {1, 2, 3};

v.at(10); // Throws out_of_range

}

catch (const out_of_range& e) {

cout << "out_of_range: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- bad_alloc: memory allocation failure ---

cout << "\n=== bad_alloc ===" << endl;

try {

// Simulate: try to allocate enormous amount

// int* p = new int[999999999999LL]; // Would throw bad_alloc

throw bad_alloc();

}

catch (const bad_alloc& e) {

cout << "bad_alloc: " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

int main() {

demonstrateStandardExceptions();

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- runtime_error: Base class for errors detectable only during execution — use for general runtime failures

- range_error: Subclass of runtime_error — mathematical results outside representable range

- overflow_error: Subclass of runtime_error — arithmetic overflow in computation

- logic_error: Base class for errors caused by bugs in program logic — preventable with correct code

- invalid_argument: Subclass of logic_error — function received invalid input argument

- out_of_range: Subclass of logic_error — access beyond valid bounds (thrown by vector::at, string::at)

- bad_alloc: Header

<new>— thrown whennewcannot allocate requested memory - All inherit from std::exception: Every standard exception has .what() returning const char*

- runtime vs logic distinction: runtime_error = unexpected failures; logic_error = programming bugs

- vector::at() auto-throws: Unlike v[i], v.at(i) bounds-checks and throws out_of_range

- bad_alloc from new: By default new throws — use

new(nothrow)for null-returning version - what() message: Constructor argument becomes the what() string

- Catch hierarchy: Can catch more specific or more general types

Output:

=== runtime_error ===

runtime_error: Something went wrong at runtime

=== range_error ===

range_error: Result outside valid range

=== overflow_error ===

overflow_error: Arithmetic overflow occurred

=== logic_error ===

logic_error: Function called with invalid arguments

=== invalid_argument ===

invalid_argument: Argument must be positive

=== out_of_range (from vector::at) ===

out_of_range: vector::_M_range_check: __n (which is 10) >= this->size() (which is 3)

=== bad_alloc ===

bad_alloc: std::bad_allocMultiple Catch Blocks and Catch-All

A single try block can have multiple catch blocks, each handling a different exception type.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

void riskyOperation(int code) {

switch (code) {

case 1: throw invalid_argument("Invalid argument provided");

case 2: throw runtime_error("Runtime failure occurred");

case 3: throw out_of_range("Index out of valid range");

case 4: throw 42; // Throw an integer

case 5: throw string("plain string exception");

default: cout << "Code " << code << " — no exception" << endl;

}

}

int main() {

cout << "=== Multiple catch blocks ===" << endl;

for (int code = 0; code <= 6; code++) {

cout << "\nTrying code " << code << ":" << endl;

try {

riskyOperation(code);

}

// Catch most specific types first

catch (const invalid_argument& e) {

cout << " [invalid_argument] " << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (const out_of_range& e) {

cout << " [out_of_range] " << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (const logic_error& e) {

// Catches any logic_error not caught above

cout << " [logic_error base] " << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << " [runtime_error] " << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (const exception& e) {

// Catches any std::exception not caught above

cout << " [std::exception base] " << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (int i) {

// Catches thrown integers

cout << " [int exception] value = " << i << endl;

}

catch (const string& s) {

// Catches thrown strings

cout << " [string exception] " << s << endl;

}

catch (...) {

// Catch-all: catches absolutely anything not caught above

cout << " [catch-all] Unknown exception caught" << endl;

}

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Multiple catch blocks: Try block followed by several catches — C++ tries them in order, top to bottom

- First matching catch wins: Only the first matching catch executes — others skipped

- Most specific first: Put derived types (invalid_argument) before base types (logic_error) — wrong order causes base to catch first

- invalid_argument before logic_error: invalid_argument IS-A logic_error — if logic_error came first, it would catch invalid_argument too

- catch (const logic_error&): Catches any unmatched logic_error and its subclasses (invalid_argument, out_of_range, etc.) if not caught earlier

- catch (const exception&): Catches all std::exception-derived types not caught above — safety net

- throw 42: C++ can throw ANY type — even primitives and user-defined types

- catch (int i): Catches thrown integers specifically — type must match exactly

- throw string(…): Throws a std::string — caught by catch(const string&)

- catch (…) (catch-all): Ellipsis catches everything — last resort when type is unknown

- catch-all use case: Preventing unhandled exceptions from terminating the program

- Can’t re-examine in catch-all: In catch(…) you don’t know what was thrown

- Order matters critically: Reversing invalid_argument and logic_error would hide specific handling

- Code 6: No exception thrown — no catch block runs, continues normally

Output:

=== Multiple catch blocks ===

Trying code 0:

Code 0 — no exception

Trying code 1:

[invalid_argument] Invalid argument provided

Trying code 2:

[runtime_error] Runtime failure occurred

Trying code 3:

[out_of_range] Index out of valid range

Trying code 4:

[int exception] value = 42

Trying code 5:

[string exception] plain string exception

Trying code 6:

Code 6 — no exceptionCustom Exception Classes

Creating your own exception classes gives you richer error information and domain-specific exception types.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// --- Base custom exception ---

class AppException : public exception {

private:

string message;

int errorCode;

public:

AppException(const string& msg, int code)

: message(msg), errorCode(code) {}

const char* what() const noexcept override {

return message.c_str();

}

int getCode() const { return errorCode; }

};

// --- Specific exceptions inheriting from AppException ---

class DatabaseException : public AppException {

private:

string query;

public:

DatabaseException(const string& msg, const string& q, int code)

: AppException(msg, code), query(q) {}

string getQuery() const { return query; }

};

class NetworkException : public AppException {

private:

string host;

int port;

public:

NetworkException(const string& msg, const string& h, int p)

: AppException(msg, 503), host(h), port(p) {}

string getEndpoint() const {

return host + ":" + to_string(port);

}

};

class ValidationException : public AppException {

private:

string field;

string value;

public:

ValidationException(const string& field, const string& value)

: AppException("Validation failed for field '" + field + "'", 400)

, field(field), value(value) {}

string getField() const { return field; }

string getValue() const { return value; }

};

// Simulated functions that throw custom exceptions

void connectToDatabase(const string& query) {

throw DatabaseException(

"Failed to execute query",

query,

1045

);

}

void connectToServer(const string& host, int port) {

throw NetworkException(

"Connection refused",

host, port

);

}

void validateAge(const string& ageStr) {

int age = stoi(ageStr);

if (age < 0 || age > 150) {

throw ValidationException("age", ageStr);

}

}

int main() {

// --- Catching specific custom exception ---

cout << "=== DatabaseException ===" << endl;

try {

connectToDatabase("SELECT * FROM users");

}

catch (const DatabaseException& e) {

cout << "DB Error [code " << e.getCode() << "]: " << e.what() << endl;

cout << "Failed query: " << e.getQuery() << endl;

}

// --- NetworkException ---

cout << "\n=== NetworkException ===" << endl;

try {

connectToServer("api.example.com", 8080);

}

catch (const NetworkException& e) {

cout << "Network Error [code " << e.getCode() << "]: " << e.what() << endl;

cout << "Endpoint: " << e.getEndpoint() << endl;

}

// --- ValidationException ---

cout << "\n=== ValidationException ===" << endl;

try {

validateAge("200");

}

catch (const ValidationException& e) {

cout << "Validation Error [code " << e.getCode() << "]: " << e.what() << endl;

cout << "Field: " << e.getField()

<< ", Value: " << e.getValue() << endl;

}

// --- Catching by base class ---

cout << "\n=== Catching all AppExceptions by base ===" << endl;

auto throwers = {

[]{ connectToDatabase("INSERT INTO logs VALUES (1)"); },

[]{ connectToServer("db.internal", 5432); },

[]{ validateAge("-5"); }

};

for (auto& thrower : throwers) {

try {

thrower();

}

catch (const AppException& e) {

cout << "AppException [" << e.getCode() << "]: " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- AppException inherits from exception: Custom base — provides what() and custom errorCode

- Override what(): Returns message as const char* — matches exception’s virtual what()

- noexcept on what(): what() must not throw — noexcept guarantees this

- Private message member: Stored as string, returned as const char* via c_str()

- getCode(): Custom accessor — provides domain-specific info not in std::exception

- DatabaseException inherits AppException: Extends with query information

- Constructor chaining: Calls AppException(…) in member initializer list

- getQuery(): Accessor for the failed SQL query — helps debugging

- NetworkException stores host/port: Domain-specific context for network errors

- ValidationException builds message: Constructs descriptive message from field and value

- Catching specific type: catch(DatabaseException&) catches only DB errors with full context

- e.getQuery(): Access methods not available on base exception class

- Catching by base AppException: Catches all three custom types through base class reference

- Polymorphism: e.what() calls the correct overridden version via virtual dispatch

- Hierarchy benefit: Client code can catch specific or general exceptions as needed

Output:

=== DatabaseException ===

DB Error [code 1045]: Failed to execute query

Failed query: SELECT * FROM users

=== NetworkException ===

Network Error [code 503]: Connection refused

Endpoint: api.example.com:8080

=== ValidationException ===

Validation Error [code 400]: Validation failed for field 'age'

Field: age, Value: 200

=== Catching all AppExceptions by base ===

AppException [1045]: Failed to execute query

AppException [503]: Connection refused

AppException [400]: Validation failed for field 'age'Stack Unwinding and RAII

When an exception is thrown, C++ unwinds the stack, calling destructors for all objects in scope—this integrates perfectly with RAII.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// RAII wrapper — destructor always runs, even during exception

class Resource {

private:

string name;

public:

Resource(const string& n) : name(n) {

cout << " [+] Acquired: " << name << endl;

}

~Resource() {

cout << " [-] Released: " << name << endl;

}

void use() {

cout << " [*] Using: " << name << endl;

}

};

void level3() {

Resource r3("Database Connection");

r3.use();

cout << " level3: about to throw" << endl;

throw runtime_error("Something failed deep in level3");

// r3 destructor called here during stack unwinding

}

void level2() {

Resource r2("File Handle");

r2.use();

cout << " level2: calling level3" << endl;

level3();

// If level3 throws, r2 destructor called during stack unwinding

cout << " level2: this won't print" << endl;

}

void level1() {

Resource r1("Network Socket");

r1.use();

cout << " level1: calling level2" << endl;

level2();

cout << " level1: this won't print" << endl;

}

int main() {

cout << "=== Stack Unwinding with RAII ===" << endl;

cout << "Calling level1..." << endl;

try {

level1();

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "\nCaught in main: " << e.what() << endl;

}

cout << "\nAll resources released — no leaks" << endl;

// --- Without RAII: resources can leak ---

cout << "\n=== WITHOUT RAII (manual management — dangerous) ===" << endl;

int* rawPtr = nullptr;

try {

rawPtr = new int[100];

cout << "Allocated raw memory" << endl;

throw runtime_error("Error before delete!");

delete[] rawPtr; // NEVER REACHED — memory leaks!

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "Caught: " << e.what() << endl;

delete[] rawPtr; // Must manually clean up in catch too

rawPtr = nullptr;

cout << "Manually cleaned up (easy to forget!)" << endl;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Resource class (RAII): Constructor acquires resource, destructor releases it

- Stack unwinding: When exception thrown, C++ destroys all local objects in reverse construction order

- level3 creates r3: Database connection acquired

- throw in level3: Exception thrown — r3 destructor called AUTOMATICALLY during unwinding

- level2’s r2 destroyed next: File handle released as level2 is unwound from the stack

- level1’s r1 destroyed last: Network socket released as level1 is unwound

- Reverse order destruction: r3 → r2 → r1 — last-constructed is first-destroyed (LIFO)

- Catch block receives exception: After full stack unwind, catch in main executes

- No resource leaks: All three resources properly released despite exception

- RAII guarantee: Resource release tied to object lifetime — impossible to leak

- Without RAII raw pointer: delete[] between throw and catch is unreachable — memory leaks

- Manual catch cleanup: Must remember to delete in catch — tedious, error-prone

- Exception in multiple catch blocks: Each catch would need its own delete — code explodes

- RAII eliminates problem: Use unique_ptr or RAII wrapper — delete runs automatically

Output:

=== Stack Unwinding with RAII ===

Calling level1...

[+] Acquired: Network Socket

[*] Using: Network Socket

level1: calling level2

[+] Acquired: File Handle

[*] Using: File Handle

level2: calling level3

[+] Acquired: Database Connection

[*] Using: Database Connection

level3: about to throw

[-] Released: Database Connection

[-] Released: File Handle

[-] Released: Network Socket

Caught in main: Something failed deep in level3

All resources released — no leaks

=== WITHOUT RAII (manual management — dangerous) ===

Allocated raw memory

Caught: Error before delete!

Manually cleaned up (easy to forget!)Rethrowing Exceptions

Sometimes you catch an exception to add context or log it, then rethrow it to let callers handle it.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

void parseConfig(const string& config) {

if (config.empty()) {

throw invalid_argument("Config string cannot be empty");

}

cout << "Parsed: " << config << endl;

}

void loadConfig(const string& filename) {

try {

string config = ""; // Simulate empty config

parseConfig(config);

}

catch (const invalid_argument& e) {

// Add context and rethrow same exception

cout << "[loadConfig] Caught and rethrowing: " << e.what() << endl;

throw; // Rethrow exactly as-is (not throw e — avoids slicing)

}

}

void initializeApp() {

try {

loadConfig("settings.cfg");

}

catch (const exception& e) {

// Wrap in more informative exception

throw runtime_error(

string("App init failed: ") + e.what()

);

}

}

int main() {

// --- Simple rethrow ---

cout << "=== Rethrow with throw; ===" << endl;

try {

loadConfig("config.txt");

}

catch (const invalid_argument& e) {

cout << "[main] Final catch: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- Wrapping in new exception ---

cout << "\n=== Exception wrapping ===" << endl;

try {

initializeApp();

}

catch (const runtime_error& e) {

cout << "[main] App error: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// --- Rethrow in catch-all ---

cout << "\n=== Rethrow from catch-all ===" << endl;

try {

try {

throw 42; // Throw an int

}

catch (...) {

cout << "Inner catch-all caught something, rethrowing..." << endl;

throw; // Rethrow the original int exception

}

}

catch (int i) {

cout << "Outer caught int: " << i << endl;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- throw; (bare throw): Rethrows the CURRENT exception without making a copy — preserves original type

- throw e; (wrong): Creates a new exception from e — potentially slices derived types

- Slicing problem: If e is a base reference to a derived object,

throw eloses derived data - Bare throw always correct: Rethrows exact original object with full type information

- Catch-then-rethrow pattern: Log or add context, then let caller handle the real error

- [loadConfig] logs and rethrows: Adds “Caught and rethrowing” message, then propagates

- [main] receives original: Gets the same invalid_argument as if loadConfig hadn’t caught

- Exception wrapping in initializeApp: Catches original, throws new runtime_error with more context

- Combining messages:

string("App init failed: ") + e.what()builds informative message - Exception chaining: Building error context as exceptions propagate up layers

- throw; from catch(…): Even catch-all can rethrow — original exception preserved

- Outer catches int: After rethrow, outer catch(int) can match the original thrown int

- Why wrap?: Lower layers use specific exceptions; higher layers may need a different type

- Library boundary: Often wrap internal exceptions into public API exceptions at module boundaries

Output:

=== Rethrow with throw; ===

[loadConfig] Caught and rethrowing: Config string cannot be empty

[main] Final catch: Config string cannot be empty

=== Exception wrapping ===

[loadConfig] Caught and rethrowing: Config string cannot be empty

[main] App error: App init failed: Config string cannot be empty

=== Rethrow from catch-all ===

Inner catch-all caught something, rethrowing...

Outer caught int: 42noexcept: Declaring Functions That Don’t Throw

The noexcept specifier communicates to callers and the compiler that a function will not throw exceptions.

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

// noexcept: function promises not to throw

int safeAdd(int a, int b) noexcept {

return a + b;

}

double safeDivide(double a, double b) noexcept {

if (b == 0.0) return 0.0; // Handle error without throwing

return a / b;

}

// noexcept with condition

template <typename T>

void swapNoexcept(T& a, T& b) noexcept(noexcept(T(T()))) {

T temp = a;

a = b;

b = temp;

}

// What happens if noexcept function DOES throw?

void badNoexcept() noexcept {

// If this throws, std::terminate() is called — program ends immediately

// throw runtime_error("This will call terminate!");

cout << "badNoexcept: running normally" << endl;

}

// Checking noexcept at compile time

void checkNoexcept() {

cout << "safeAdd noexcept: "

<< noexcept(safeAdd(1, 2)) << endl;

cout << "safeDivide noexcept: "

<< noexcept(safeDivide(1.0, 2.0)) << endl;

vector<int> v;

cout << "vector::push_back noexcept: "

<< noexcept(v.push_back(1)) << endl;

cout << "vector::swap noexcept: "

<< noexcept(v.swap(v)) << endl;

}

int main() {

cout << "=== noexcept functions ===" << endl;

cout << "safeAdd(3, 4) = " << safeAdd(3, 4) << endl;

cout << "safeDivide(10.0, 0.0) = " << safeDivide(10.0, 0.0) << endl;

cout << "safeDivide(10.0, 3.0) = " << safeDivide(10.0, 3.0) << endl;

cout << "\n=== noexcept query ===" << endl;

checkNoexcept();

cout << "\n=== badNoexcept (safe call) ===" << endl;

badNoexcept();

cout << "\n=== noexcept in move operations ===" << endl;

// Move constructors should be noexcept for STL optimization

cout << "vector optimizes moves when noexcept(true)" << endl;

cout << "If move constructor is noexcept, vector uses move during reallocation" << endl;

cout << "Otherwise vector falls back to copying (safe but slower)" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- noexcept specifier: Declares function will not throw any exception

- Optimization opportunity: Compiler can optimize code paths, knowing no exception cleanup needed

- safeDivide with noexcept: Handles error by returning 0 instead of throwing

- noexcept(condition): Conditional noexcept — noexcept only if condition is true

- noexcept(noexcept(T(T()))): True if T’s default construction doesn’t throw

- If noexcept function throws: C++ calls std::terminate() immediately — no catch block reached

- terminate() ends program: Calls abort() by default — no graceful recovery

- noexcept(expr) as operator: Returns true/false at compile time — doesn’t execute expr

- noexcept(safeAdd(1,2)): Returns true — safeAdd is marked noexcept

- vector::push_back not noexcept: May throw bad_alloc — can’t be noexcept

- vector::swap is noexcept: Just swaps internal pointers — cannot throw

- Move constructor + noexcept: Critical for STL performance

- vector reallocation: Uses move if noexcept, copy if not — ensures strong exception guarantee

- Rule: Mark move constructors, move assignment, swap, and destructors as noexcept

Output:

=== noexcept functions ===

safeAdd(3, 4) = 7

safeDivide(10.0, 0.0) = 0

safeDivide(10.0, 3.0) = 3.33333

=== noexcept query ===

safeAdd noexcept: 1

safeDivide noexcept: 1

vector::push_back noexcept: 0

vector::swap noexcept: 1

=== badNoexcept (safe call) ===

badNoexcept: running normally

=== noexcept in move operations ===

vector optimizes moves when noexcept(true)

If move constructor is noexcept, vector uses move during reallocation

Otherwise vector falls back to copying (safe but slower)

Exception Safety Guarantees

Well-designed C++ functions provide one of four exception safety levels.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// --- No-throw guarantee ---

// Function either succeeds or has no observable effect

// Use noexcept to document this

void swapValues(int& a, int& b) noexcept {

int temp = a;

a = b;

b = temp;

}

// --- Strong exception guarantee ---

// Function either fully succeeds or leaves object completely unchanged

class StrongSafe {

private:

vector<int> data;

public:

// Strong guarantee via copy-and-swap

void addAll(const vector<int>& newData) {

vector<int> temp = data; // Make a copy

for (int n : newData) {

temp.push_back(n); // May throw bad_alloc

}

data.swap(temp); // noexcept swap — can't fail

// If push_back threw, original data unchanged

}

const vector<int>& getData() const { return data; }

};

// --- Basic exception guarantee ---

// Object remains in valid but unspecified state after exception

class BasicSafe {

private:

vector<string> items;

int count = 0;

public:

void addItem(const string& item) {

items.push_back(item); // May throw bad_alloc

++count; // Only reached if push_back succeeded

// Object is valid but state may be unexpected

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Strong Exception Guarantee ===" << endl;

StrongSafe ss;

// Add first batch successfully

ss.addAll({1, 2, 3});

cout << "After addAll({1,2,3}): ";

for (int n : ss.getData()) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// Simulate: if addAll throws, data is unchanged

cout << "Strong guarantee: if addAll throws, data stays as {1,2,3}" << endl;

cout << "\n=== No-throw Guarantee ===" << endl;

int a = 10, b = 20;

cout << "Before: a=" << a << ", b=" << b << endl;

swapValues(a, b);

cout << "After swap: a=" << a << ", b=" << b << endl;

cout << "swapValues is noexcept — always succeeds" << endl;

cout << "\n=== Exception Safety Levels ===" << endl;

cout << "1. No-throw (noexcept): Always succeeds — swap, destructor, simple ops" << endl;

cout << "2. Strong: Either succeeds or no observable change — copy-and-swap" << endl;

cout << "3. Basic: Object valid but unspecified state — most STL operations" << endl;

cout << "4. No guarantee: Object may be corrupted — avoid this" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- No-throw guarantee: Function marked noexcept — guaranteed never to throw

- Best possible guarantee: Callers can use without any try-catch

- Strong guarantee: Operation either completes entirely or leaves object exactly as before

- Copy-and-swap for strong: Make a copy, modify copy, swap if successful — original untouched on throw

- temp copy of data: If push_back throws, temp is discarded, original data unchanged

- swap is noexcept: The commit step cannot fail — guarantees atomicity

- Either-or semantics: Like a database transaction — commits fully or rolls back

- Basic guarantee: Object remains in a valid, usable state but exact state is unspecified

- count only incremented after push_back: Ensures count stays consistent

- Valid but unspecified: Object can still be used, but its exact state depends on where failure occurred

- No guarantee: Object may be in invalid state — never acceptable in production code

- Hierarchical: Strong implies basic; basic implies object is still usable

- Design for your needs: Not every function needs strong guarantee — performance cost

- Destructors must be no-throw: Throwing in destructor during stack unwinding calls terminate()

Best Practices Summary

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <memory>

using namespace std;

int main() {

cout << "=== C++ Exception Handling Best Practices ===" << endl;

// BEST PRACTICE 1: Catch by const reference

try {

throw runtime_error("test");

}

catch (const exception& e) { // const reference — no copy, no slicing

cout << "1. Catch by const reference: " << e.what() << endl;

}

// BEST PRACTICE 2: Throw by value

// throw MyException("msg"); // Correct — throw temporary (by value)

// throw &myEx; // WRONG — pointer to local variable

// BEST PRACTICE 3: Use RAII — no raw resource management

{

auto ptr = make_unique<int>(42); // RAII — auto-released

// throw runtime_error("test"); // ptr still released!

cout << "2. RAII: *ptr = " << *ptr << endl;

}

// BEST PRACTICE 4: Don't throw from destructors

struct SafeDestructor {

~SafeDestructor() noexcept {

try {

// risky cleanup

}

catch (...) {

// Swallow — never let destructor throw

}

}

};

cout << "3. Destructors must not throw (mark noexcept)" << endl;

// BEST PRACTICE 5: Don't use exceptions for flow control

// WRONG: using exception as a "found/not found" signal

// RIGHT: use find_if, count, contains etc. for expected conditions

// BEST PRACTICE 6: Document what functions throw

// Use /// @throws runtime_error if file not found

cout << "4. Document thrown exceptions in comments/docs" << endl;

// BEST PRACTICE 7: Prefer specific exception types

try {

throw invalid_argument("Be specific");

}

catch (const invalid_argument& e) { // Specific catch

cout << "5. Specific: " << e.what() << endl;

}

return 0;

}Best practices summary:

- Catch by const reference:

catch (const exception& e)— avoids copying, prevents slicing - Throw by value:

throw MyException(args)— never throw pointers to local variables - Use RAII: Wrap resources in smart pointers or RAII classes — auto-cleanup on exception

- Destructors must not throw: Mark destructors noexcept, swallow exceptions inside them

- Don’t use for flow control: Exceptions are for exceptional conditions — not found/empty are normal

- Document exceptions: Comment what functions throw and under what conditions

- Be specific: Prefer

invalid_argumentover genericexception— better information for callers - Use catch-all sparingly: Only as a last resort to prevent program termination

- Order catches correctly: Most specific types first, base types last

- Avoid exception specifications (old style): Don’t use

throw(T)— deprecated in C++11, removed in C++17

Conclusion: Robust Programs Through Exception Handling

Exception handling is not just a language feature—it’s a philosophy for building reliable software. By separating the “happy path” from error handling, using RAII to guarantee resource cleanup, and leveraging the standard exception hierarchy for consistent error reporting, you can write C++ programs that handle failures gracefully rather than crashing or silently corrupting data.

Key takeaways:

- try-catch-throw: The three keywords that form the core — try watches for exceptions, throw signals them, catch handles them

- Catch by const reference: Always use

catch (const SomeException& e)— no copies, no slicing - Exception hierarchy: Standard exceptions inherit from

std::exception— catch bases to handle families - Custom exceptions: Inherit from std::exception or its subclasses — always override what() with noexcept

- Multiple catch blocks: Order from most specific to most general — first matching catch wins

- Stack unwinding: Destructors run automatically during exception propagation — RAII guarantees cleanup

- Rethrow: Use bare

throw;to rethrow without slicing — notthrow e; - noexcept: Documents and enforces no-throw contracts — enables compiler optimizations

- Exception safety guarantees: Design functions to provide no-throw, strong, or basic guarantees

- Destructors must not throw: Mark them noexcept and swallow any internal exceptions

Master exception handling, and you’ll write C++ that fails gracefully, communicates errors clearly, and never leaks resources — the hallmarks of professional-quality software.