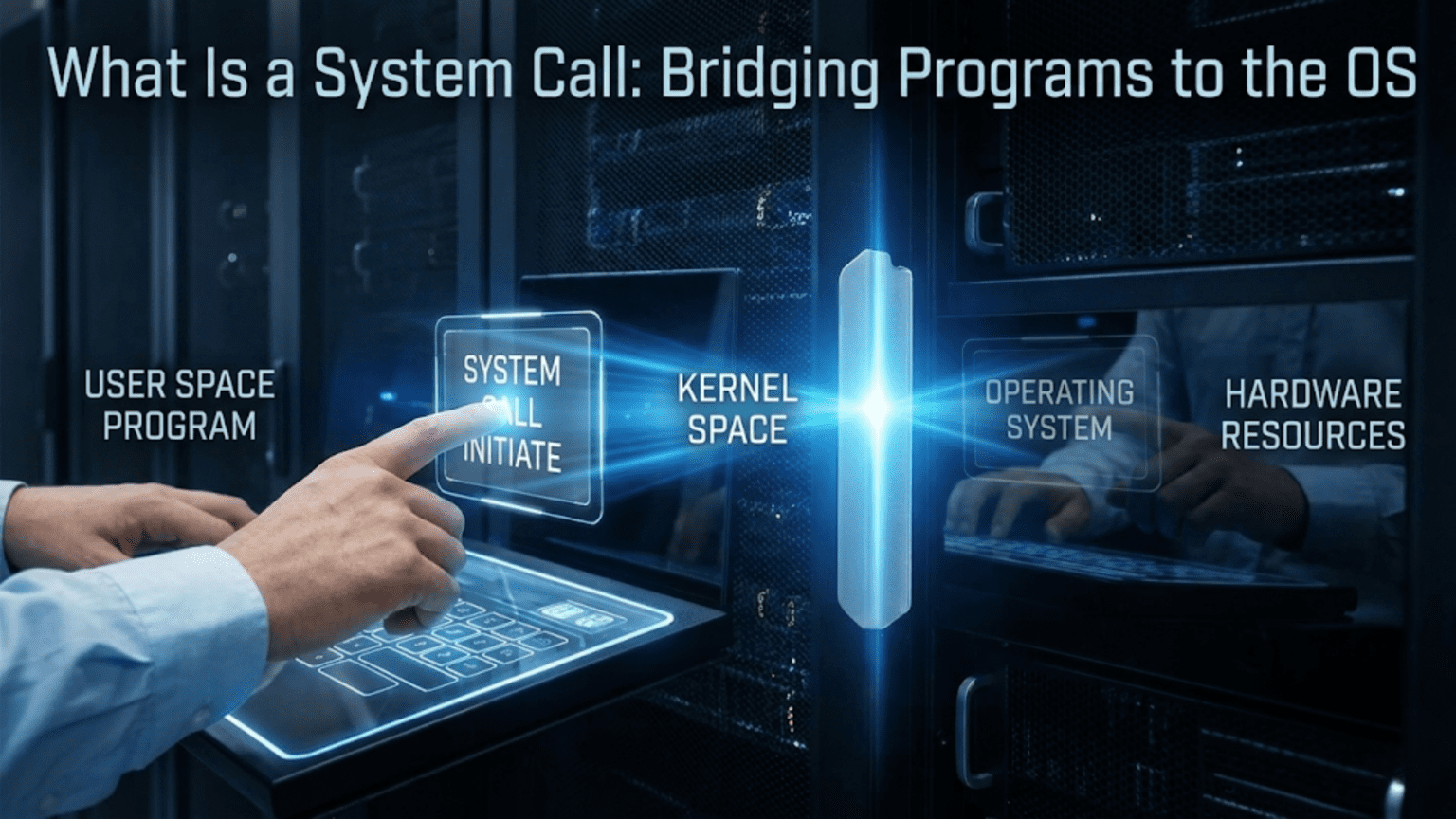

Every time you save a file, send an email, or play a video on your computer, something remarkable happens beneath the surface. Your application, running in its own protected space with limited privileges, needs to ask the operating system to perform actions on its behalf. This conversation between applications and the operating system happens through a mechanism called system calls, and understanding this mechanism is fundamental to understanding how modern computers actually work.

Think of system calls as the formal language that programs use when they need the operating system’s help. Just as you might walk up to a service counter and make a specific request using certain phrases and procedures, programs make specific requests to the operating system using a well-defined protocol. The program can’t just reach into the operating system and do what it wants. Instead, it must politely ask, following the proper procedure, and wait for the operating system to fulfill the request and report back with the results.

This structured interaction isn’t just a matter of politeness or organization. It’s a fundamental security mechanism that protects the system from misbehaving programs, ensures that different programs don’t interfere with each other, and allows the operating system to mediate access to shared resources like files, network connections, and hardware devices. Without system calls, your computer would be chaos, with programs potentially corrupting each other’s data, crashing the entire system, or creating security vulnerabilities.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll dive deep into the world of system calls. We’ll start by understanding why they exist and what problem they solve. Then we’ll examine exactly how system calls work at a technical level, what happens when a program makes a system call, and what kinds of services the operating system provides through this mechanism. We’ll look at real examples of system calls in action, explore the performance implications, and understand how this seemingly simple concept enables the complexity and security of modern computing. By the end, you’ll have a thorough understanding of one of the most important interfaces in computer science.

The Fundamental Problem: Privilege and Protection

To understand why system calls exist, we need to understand a fundamental principle of modern operating systems: privilege separation. Not all code running on your computer has the same level of access to the hardware and system resources. There’s a clear hierarchy of privilege, and this hierarchy is enforced by the processor hardware itself.

At the highest level of privilege sits the operating system kernel. The kernel is the core of the operating system, the part that has complete, unrestricted access to all hardware and all system resources. The kernel can directly manipulate processor registers, access any location in memory, control hardware devices, and execute any instruction the processor supports. This absolute power is necessary because the kernel must manage all the hardware and coordinate all the activities happening on the system.

Below the kernel in privilege level sit normal user programs, which we often call user-space applications or user-mode code. These programs run with restricted privileges. They can’t directly access most hardware. They can’t read or write arbitrary locations in memory, they can only access their own allocated memory. They can’t execute certain powerful processor instructions that could affect system stability or security. This restriction is enforced by the processor hardware itself, which tracks what privilege level the currently executing code has and prevents unprivileged code from doing privileged things.

This separation creates a problem. User programs constantly need to do things that require kernel privileges. When you save a file, that requires writing to a storage device, which is a privileged operation. When you send data over the network, that requires controlling network hardware, which is privileged. When you create a new window on the screen, that requires coordinating with the display system, which is managed by the kernel. Virtually everything useful that a program wants to do requires kernel involvement at some level.

The solution to this problem is the system call mechanism. A system call is a controlled way for user-space programs to request services from the kernel. It’s a special kind of function call that crosses the boundary between user space and kernel space, transferring execution from the unprivileged user program to the privileged kernel, allowing the kernel to perform the requested operation on behalf of the program, and then safely returning control back to the user program with the results.

This mechanism solves the privilege problem elegantly. User programs don’t need unrestricted hardware access because they can ask the kernel to perform operations for them. The kernel can examine each request, verify that it’s safe and authorized, perform the operation using its privileges, and return the results. This way, user programs get the services they need while the system maintains security and stability.

Anatomy of a System Call

When a program makes a system call, a carefully choreographed sequence of events unfolds. Understanding this sequence reveals the elegant engineering that makes system calls work efficiently while maintaining security.

Let’s walk through what happens when a program wants to read data from a file. The program calls a function like read(), which might look like an ordinary function call in your programming language. However, this function is special. It’s part of what we call the C standard library or system library, which provides a convenient wrapper around the system call mechanism.

Inside this library function, the code prepares for the system call. It takes the parameters you provided, such as which file to read from, where to put the data, and how much data to read, and arranges them in the specific way the operating system expects. Different operating systems have different conventions for how to pass parameters during system calls. On many systems, parameters are placed in specific processor registers. On others, they might be pushed onto the stack or placed in a designated memory area.

Once the parameters are arranged, the library function executes a special processor instruction designed specifically for making system calls. This might be an instruction called SYSCALL on modern x86-64 processors, or INT 0x80 on older systems, or SVC on ARM processors. The exact instruction varies by processor architecture, but they all serve the same purpose: they trigger a controlled transition from user mode to kernel mode.

When this instruction executes, several things happen at the hardware level. The processor saves the current state of the user program, including where it was executing and the contents of various registers, so it can resume later. It switches from user mode to kernel mode, changing its privilege level. It jumps to a specific location in kernel memory where the operating system has placed its system call handler code. And it does all of this atomically, meaning in one indivisible operation that can’t be interrupted or subverted.

Now executing in kernel mode, the operating system’s system call handler takes over. It first validates the system call request. It checks whether the requested system call number is valid, whether the parameters make sense, and whether the calling program has permission to perform this operation. If anything looks wrong, the kernel can reject the request immediately without performing any potentially dangerous operation.

If the request is valid, the kernel performs the actual work. For a file read operation, this might involve checking whether the file is already in memory cache, reading it from the storage device if not, copying the requested data into the program’s memory space, and updating various internal data structures that track file access. This work happens with full kernel privileges, allowing the kernel to access hardware and manipulate system state as needed.

Once the operation completes, the kernel prepares to return control to the user program. It places the result of the operation, such as how many bytes were successfully read or an error code if something went wrong, in a designated location where the user program can find it, typically a processor register or the program’s stack. It then executes a return-from-system-call instruction that reverses the earlier transition, switching back from kernel mode to user mode and resuming execution in the user program right after the system call instruction.

Back in user space, the library function that initiated the system call retrieves the result, possibly processes it into a more convenient form, and returns it to your program. From your program’s perspective, it simply called a function and got a result back, but behind the scenes, this elaborate dance occurred to safely cross the privilege boundary and allow kernel services to execute on your behalf.

Categories of System Calls: What Services Do Operating Systems Provide?

Operating systems provide hundreds of different system calls, each offering a specific service to user programs. These system calls can be organized into several broad categories based on what kind of service they provide. Understanding these categories helps you appreciate the full scope of what the operating system does for programs.

The largest and arguably most important category is file and filesystem operations. Programs constantly need to work with files, whether reading configuration settings, saving user documents, loading data, or logging information. System calls in this category allow programs to create files, delete files, open files for reading or writing, read data from files, write data to files, seek to specific positions within files, change file permissions, create directories, list directory contents, and perform many other filesystem operations. Examples include open(), read(), write(), close(), unlink(), mkdir(), and stat(). These system calls shield programs from the complexity of different filesystem formats, storage devices, and caching systems, providing a uniform interface regardless of whether the file lives on a hard drive, solid-state drive, network storage, or removable media.

Process management represents another critical category. Programs need to create new processes, wait for processes to finish, terminate processes, and communicate between processes. System calls like fork(), exec(), wait(), exit(), and kill() provide these capabilities. When you run a program from the command line, the shell uses these system calls to create a new process for your program. When one program launches another, it uses these calls. When programs need to work together, sharing data or coordinating their activities, they rely on these process management system calls.

Memory management system calls allow programs to request memory from the operating system, return memory they no longer need, and manage how memory is mapped and protected. Calls like brk(), mmap(), munmap(), and mprotect() give programs control over their memory usage. When you see a program’s memory usage grow or shrink, that’s happening through these system calls. These calls also enable advanced features like memory-mapped files, where a file can be accessed as if it were just memory, and shared memory, where multiple programs can access the same memory region for fast communication.

Inter-process communication, or IPC, system calls enable programs to communicate and synchronize with each other. Pipes, which allow one program’s output to flow into another program’s input, are created and used through system calls like pipe() and the usual read() and write() calls. Signals, which allow one process to notify another of events or request actions, use system calls like kill() and signal(). Message queues, semaphores, and shared memory segments each have their own sets of system calls for creation, access, and management.

Network operations form another major category. Programs need to create network connections, send and receive data over networks, and manage network resources. System calls like socket(), bind(), listen(), accept(), connect(), send(), and recv() provide the building blocks for all network communication. Whether you’re browsing the web, checking email, streaming video, or playing online games, your programs are using these network-related system calls continuously.

Device I/O and control system calls allow programs to interact with hardware devices. While many devices are accessed through the filesystem interface, making them look like special files, specific device control operations often require dedicated system calls like ioctl(). These calls let programs configure devices, query their status, and perform device-specific operations that don’t fit into the standard read/write model.

Time and clock-related system calls let programs query the current time, set timers, and sleep for specified periods. Calls like time(), gettimeofday(), clock_gettime(), and nanosleep() are essential for programs that need to track when events occur, implement timeouts, or schedule activities.

Security and permission-related system calls allow programs to manage user identities, change permissions, and implement security policies. Calls like getuid(), setuid(), chmod(), and chown() let programs work within the operating system’s security model, checking whether actions are authorized and modifying security attributes when appropriate.

This categorization isn’t exhaustive, and many system calls don’t fit neatly into a single category. The important point is that operating systems provide a rich set of services through system calls, covering virtually everything a program might need to do that requires kernel privileges or access to shared resources.

Real Examples: System Calls in Action

To make system calls concrete, let’s examine some real examples of how programs use them in common scenarios. Seeing these examples helps bridge the gap between the abstract concept and the practical reality.

Imagine you’ve written a simple program that reads a text file and counts how many times the word “hello” appears. This seemingly straightforward task involves multiple system calls working together. When your program starts, it first needs to open the file. It calls the open() system call, passing the filename and specifying that it wants to read the file. The kernel checks whether the file exists, whether your program has permission to read it, and if everything is okay, it sets up the necessary internal data structures and returns a file descriptor, which is just a small integer that serves as a handle to refer to this open file.

Now your program repeatedly reads chunks of data from the file using the read() system call. Each call specifies the file descriptor, a memory buffer where the data should be placed, and how many bytes to read. The kernel retrieves data from the file, which might involve reading from a disk cache if the data was recently accessed, or actually reading from the physical storage device if not, and copies it into your program’s memory. The kernel returns how many bytes were actually read, which might be less than requested if the end of the file is reached.

Your program processes each chunk of data, searching for the word “hello”. This processing happens entirely in user space without any system calls. But when your program has read all the data, it needs to close the file using the close() system call. This tells the kernel that you’re done with the file, allowing it to free up resources and clean up its internal data structures.

Finally, when your program wants to report the result, it might use the write() system call to send output to the terminal. This writes to a special file descriptor that represents standard output, and the kernel handles getting that data displayed on your screen.

Consider another example: a web browser loading a web page. This involves a complex orchestration of many different system calls. First, the browser needs to establish a network connection to the web server. It creates a network socket using the socket() system call, which sets up a communication endpoint. Then it calls connect(), providing the server’s address, and the kernel establishes a TCP connection to the remote server, handling all the low-level networking protocol details.

Once connected, the browser sends an HTTP request to the server using the send() or write() system call. The kernel takes the data your program provides, packages it into network packets according to the TCP protocol, and sends it over the network interface. The browser then waits for a response using the recv() or read() system call. This call might block, meaning the program stops and waits, until data arrives from the network. The kernel handles receiving network packets, reassembling them according to the TCP protocol, and making the data available to your program.

As the web page data arrives, the browser might need to create temporary files to store images or other resources, involving the same open(), write(), close() sequence we saw earlier. If the web page includes JavaScript that creates timers or animations, the browser uses time-related system calls to schedule periodic work. If it needs to spawn a helper process to handle certain file types, it uses fork() and exec() system calls.

Throughout all of this, the browser is probably using memory management system calls to allocate memory for storing the page content, parsed data structures, and rendered graphics. It might use mmap() to map image files directly into memory for efficient access.

These examples illustrate how system calls are the fundamental building blocks that programs use to accomplish real work. Every interaction with the outside world, every access to a file or device, every communication with another program or computer, flows through system calls.

The Performance Perspective: System Calls Are Expensive

While system calls are essential, they come with a significant performance cost. Understanding this cost is important for writing efficient programs and appreciating the design decisions in operating systems.

The fundamental issue is that each system call involves a context switch, changing from user mode to kernel mode and back. This transition isn’t free. The processor must save the current program’s state, including all relevant registers, so it can be restored later. It must switch to the kernel’s address space and execution context. When the system call completes, all of this must be reversed. On modern processors, a context switch might take hundreds or even thousands of processor cycles, which sounds fast in absolute terms but is slow compared to simply executing instructions within a program.

Beyond the basic transition cost, many system calls involve substantial work in the kernel. Reading from a file might require complex operations: checking caches, potentially reading from a storage device, updating access times, and managing locks to ensure data consistency. Network operations might involve protocol processing, packet manipulation, and coordination with network hardware. These operations take time, during which your program is waiting.

Because system calls are expensive, reducing their frequency is an important optimization technique. This is why programs and libraries implement buffering. When you write a single character to a file in a programming language, that data usually doesn’t immediately trigger a write() system call. Instead, it goes into a buffer in your program’s memory. Only when the buffer fills up, or when you explicitly flush it, or when your program closes the file, does the library make a write() system call to send a large chunk of data all at once. This amortizes the system call cost over many small write operations, dramatically improving performance.

Similarly, when reading from a file, the library might read a large chunk even if you only asked for a few bytes, storing the extra data in a buffer. Subsequent read requests can be satisfied from this buffer without additional system calls until the buffer is exhausted. This is why reading a file one character at a time using buffered I/O is reasonably efficient even though each individual character read would be terribly slow if it required a separate system call.

Operating systems themselves implement similar optimizations. File data is cached in memory, so repeatedly reading the same file data can be satisfied from the cache without actually accessing the storage device. Network data might be buffered in the kernel, allowing multiple small packets to be processed together.

Modern operating systems also provide alternative mechanisms for certain operations that avoid system call overhead in common cases. For instance, some systems allow programs to map files directly into their address space using mmap(), so reading from the file becomes just reading from memory with no system call for each access. Shared memory can allow programs to communicate without system calls for each message. Timer mechanisms might allow programs to register callbacks that fire periodically without repeated system calls to check the time.

The performance cost of system calls influences how we design software. High-performance programs minimize system calls, batching operations together when possible. They use asynchronous I/O mechanisms that allow them to submit many operations at once and get notified when they complete, rather than making blocking system calls one at a time. They take advantage of kernel features designed to reduce system call overhead.

Understanding that system calls are expensive helps explain many aspects of system behavior and performance. It explains why buffering is so important, why asynchronous programming models exist, and why certain operations are fast while others are slow.

System Call Interfaces Across Different Operating Systems

While the concept of system calls is universal across modern operating systems, the specific system calls available and how they work varies between systems. Understanding these variations helps appreciate both the commonalities and the differences in operating system design.

Unix-like systems, including Linux, macOS, BSD variants, and others, share a common heritage and similar system call interfaces. They all provide system calls like open(), read(), write(), close(), fork(), exec(), and many others inherited from the original Unix design. However, each system has evolved its own extensions and variations. Linux, for example, has system calls specific to its features, like epoll() for efficient I/O event notification, or cgroups-related calls for resource management. macOS has system calls related to its Mach kernel foundation and specific features like Grand Central Dispatch.

The specific numbers assigned to system calls differ between these systems. System call number one might be exit() on one system but write() on another. This means programs compiled for Linux won’t run on macOS without recompilation, even though both are Unix-like and provide similar functionality. The system call interface is part of what defines the binary compatibility of an operating system.

Windows takes a different approach entirely. While it has a kernel that provides services similar to Unix systems, it doesn’t expose these services directly as system calls in the same way. Instead, Windows provides a large set of API functions through system libraries like kernel32.dll and ntdll.dll. Programs call these library functions, which then interact with the kernel through mechanisms that are somewhat more opaque than traditional system calls. This abstraction layer gives Microsoft more flexibility to change the underlying implementation without breaking existing programs.

However, Windows does have what it calls “native API” functions in ntdll.dll that are more directly analogous to Unix system calls. These are less documented and generally not intended for direct use by application programmers, who are encouraged to use the higher-level Win32 API instead. But they exist and serve similar purposes to Unix system calls, providing the low-level interface to kernel services.

The philosophical difference reflects different design priorities. Unix systems tend to provide a relatively small set of primitive operations that can be composed in flexible ways. Windows tends to provide a larger set of higher-level operations that handle common use cases but might be less composable. Both approaches have merits, and both successfully support rich application ecosystems.

Modern operating systems also provide standardized interfaces that abstract over system-level differences. POSIX, for example, defines a standard set of system calls and library functions that conforming systems must provide. This allows programs written to the POSIX standard to run on any POSIX-compliant system with recompilation. Most Unix-like systems are substantially POSIX-compliant, though they all include extensions beyond what POSIX requires.

Programming language runtime systems often abstract over operating system differences. When you open a file in Python or Java, the language runtime handles calling the appropriate underlying system calls or API functions for whatever operating system it’s running on. This allows the same high-level code to work across different operating systems without the programmer needing to know about system call differences.

Understanding that different systems have different system call interfaces, but similar concepts, helps explain why porting software between operating systems requires work even when the systems seem similar. It also highlights the value of standardization efforts like POSIX and the portability benefits of using higher-level abstractions.

System Calls and Security

System calls play a crucial role in operating system security. They’re the chokepoint through which all user programs must pass to access protected resources, making them an ideal place to enforce security policies.

Every system call is an opportunity for the kernel to check whether the requesting program should be allowed to perform the requested operation. When you try to open a file, the kernel checks whether you have permission to read or write that file based on the file’s permissions and your user identity. When you try to send data over a network socket, the kernel can enforce firewall rules. When you try to access a hardware device, the kernel verifies you have the necessary privileges.

This security checking is fundamental to multi-user systems. On a system with multiple users, each user’s programs run with their own identity, and the kernel uses this identity when checking permissions during system calls. This prevents one user’s programs from accessing another user’s private files, ensures system files can’t be modified by unprivileged users, and generally maintains isolation between different users’ activities.

Modern security mechanisms build on this foundation. Mandatory access control systems like SELinux or AppArmor work by adding additional security checks during system calls beyond the traditional Unix permission model. These systems can enforce complex policies about what programs can access which resources, even overriding what traditional file permissions might allow.

Sandboxing, where potentially untrusted programs run with restricted capabilities, works by filtering system calls. A sandboxed program might be prevented from making certain system calls entirely, or certain system call parameters might be restricted. For example, a sandboxed web browser might be prevented from accessing most files outside a specific directory, achieved by intercepting file-related system calls and rejecting those that would access prohibited locations.

Container technologies use system call filtering as a key security mechanism. Containers might limit what system calls their processes can make, preventing them from performing potentially dangerous operations even if a vulnerability is exploited.

System calls are also important for security auditing. Many systems can log all system calls made by specific programs, creating an audit trail of what the program did. This is invaluable for security analysis, allowing administrators to detect suspicious behavior or investigate security incidents after they occur.

However, the system call interface also presents security challenges. Bugs in how the kernel handles system calls can be exploited by malicious programs. A kernel bug that fails to properly validate system call parameters might allow a program to access memory it shouldn’t, potentially compromising the entire system. This is why kernel developers pay such careful attention to input validation in system call handlers and why kernel security vulnerabilities are treated so seriously.

Race conditions, where the kernel’s security checks are invalidated between when they’re performed and when the actual operation occurs, are a classic security problem in system call handling. These time-of-check-to-time-of-use vulnerabilities have led to numerous security issues over the years and require careful programming to prevent.

The security aspects of system calls highlight why the privilege separation between user space and kernel space is so important and why the controlled crossing of this boundary through well-defined system calls is fundamental to system security.

Advanced Topics: Asynchronous System Calls and I/O Models

Most of our discussion has focused on synchronous system calls, where the program makes a call and waits for it to complete before continuing. However, waiting for system calls to complete can be inefficient for programs that need to handle multiple operations simultaneously. This has led to the development of asynchronous system call models.

In a synchronous model, when you call read() to read from a network socket, your program stops and waits until data arrives. If you need to monitor multiple sockets, you can’t just call read() on each one because you’d get stuck waiting on the first one that doesn’t have data ready. This led to the development of system calls like select() and poll(), which allow a program to wait for any of multiple file descriptors to become ready for I/O.

These calls improved the situation, allowing a single thread to monitor multiple I/O sources efficiently. However, they still involve the program being blocked, waiting in the kernel for something to happen. More advanced asynchronous I/O mechanisms have been developed to address this.

Linux’s epoll() system call provides an efficient way to monitor large numbers of file descriptors for activity. Programs can register interest in specific events on specific descriptors, and when any registered event occurs, the kernel notifies the program. This allows programs to handle thousands of simultaneous network connections efficiently, which is crucial for high-performance servers.

True asynchronous I/O, where programs can issue I/O operations that complete in the background while the program continues executing, is available through mechanisms like Linux’s io_uring or the POSIX AIO interface. These systems allow programs to submit I/O requests that the kernel processes independently, notifying the program when they complete. This enables highly concurrent programming models where a program can have many outstanding I/O operations simultaneously.

Windows has its own asynchronous I/O model through mechanisms like I/O completion ports and overlapped I/O. These allow Windows programs to perform I/O efficiently without blocking threads, supporting the high-performance servers that run on Windows systems.

These asynchronous models add considerable complexity to both the kernel and application programming. The kernel must track outstanding asynchronous operations, process them appropriately, and notify programs efficiently when they complete. Programs must be structured to handle I/O completion events asynchronously rather than sequentially, which is often more difficult to program correctly.

Modern programming languages and frameworks often provide higher-level abstractions over these asynchronous system call mechanisms. Async/await syntax in languages like Python, JavaScript, and C# allows programmers to write code that looks sequential but actually executes asynchronously, with the language runtime handling the complex coordination with the operating system’s asynchronous I/O facilities.

Understanding these asynchronous models is important for appreciating how high-performance network servers, databases, and other I/O-intensive programs achieve their performance. It also demonstrates how operating systems continue to evolve their system call interfaces to meet the changing needs of applications.

Virtual System Calls and Optimizations

Operating system designers continually seek ways to reduce the overhead of system calls while maintaining security and isolation. This has led to several interesting optimizations and alternative mechanisms that blur the line between traditional system calls and other forms of kernel services.

One optimization is the virtual dynamic shared object, or vDSO on Linux systems. For certain very frequently called system calls that don’t require full kernel privileges, the kernel can map a special memory page into every process that contains code to perform these operations without actually entering the kernel. Functions like getting the current time can often be implemented this way because the kernel can map a memory page containing the current time value that programs can read directly. This avoids the system call overhead entirely for these common operations.

The vDSO mechanism works by providing a library that appears to be in user space but is actually provided by the kernel. Programs call functions in this library thinking they’re making system calls, but the actual implementation just reads shared memory or performs other operations that don’t require kernel mode. For operations that do require kernel mode, the vDSO functions fall back to making real system calls.

Similar concepts exist in other operating systems. The idea is to provide the programming interface and security properties of system calls while avoiding the performance cost when possible.

Another optimization involves batching system calls together. Some operating systems provide mechanisms to submit multiple related operations in a single transition to kernel mode. This amortizes the context switch cost across multiple operations. The io_uring interface in Linux is partly designed around this idea, allowing programs to submit many I/O operations at once.

Kernel bypass mechanisms take optimization even further for specific use cases. In high-performance networking, some systems allow trusted programs to access network hardware more directly, bypassing much of the kernel’s networking stack. This is used in specialized applications like high-frequency trading systems where every microsecond matters. However, it trades off the safety and generality of traditional system calls for raw performance in specific scenarios.

User-space device drivers represent another area where traditional system call models are being reconsidered. Rather than having device drivers in the kernel where they can interact with hardware directly, some systems support drivers that run in user space and use special protocols to coordinate with minimal kernel support. This can improve system stability since bugs in user-space drivers can’t crash the kernel.

These optimizations and alternatives don’t replace traditional system calls, but they demonstrate the ongoing evolution of operating system interfaces. The goal remains providing programs with the services they need while maintaining security and performance, but the specific mechanisms continue to evolve.

System Calls in Practice: Programming Examples

To make system calls even more concrete, let’s look at actual code examples showing how programmers use system calls in real programs. These examples use C, which provides fairly direct access to system calls through library functions.

Here’s a simple example of reading from a file using system calls directly. In C, you might write something like this. First, you open the file by calling open, passing the filename and flags indicating you want to read, and the system returns a file descriptor which is an integer handle. Then you can call read repeatedly, passing the file descriptor, a buffer to receive the data, and how much to read, and the system returns how many bytes were actually read. When you’re done, you call close with the file descriptor to close the file.

The code would handle errors at each step, checking whether open returned minus one indicating failure, whether read returned minus one for errors, and so on. The actual system calls are happening inside these library functions, but from the programmer’s perspective, they’re just function calls that happen to interact with the kernel.

Network programming provides another good example. To create a server that listens for network connections, you would start by calling socket to create a network socket, specifying the protocol family and type. Then you’d call bind to associate the socket with a specific network address and port number. Next, listen tells the kernel you’re ready to accept connections on this socket. Finally, you’d call accept in a loop, which blocks waiting for incoming connections and returns a new socket for each connection.

For each connected client, you’d use read and write system calls to receive and send data over the network connection, treating the socket much like a file. When done with a connection, you’d close its socket.

Process creation demonstrates another important category of system calls. In Unix-like systems, creating a new process involves calling fork, which creates an exact copy of the current process. Both the parent and child process continue executing from the same point, but fork returns different values to each so they can take different paths. The child process typically calls exec to replace itself with a new program, while the parent might call wait to wait for the child to finish.

These programming examples show how system calls form the foundation of practical programming. Higher-level languages provide abstractions that hide these details, but ultimately, all file I/O, network communication, process creation, and other interactions with the operating system flow through system calls.

System Call Wrappers and Standard Libraries

While we’ve been discussing system calls as direct interactions with the kernel, in practice, programs rarely make system calls directly. Instead, they use wrapper functions provided by standard libraries. Understanding this layering helps clarify how system calls fit into the overall programming model.

The C standard library, often called libc, provides wrapper functions for most system calls. When you call open() in a C program, you’re actually calling a library function that prepares the parameters and makes the actual system call. This library function might do additional work beyond just triggering the system call, such as setting errno on errors or handling signal interruptions.

These wrappers serve several purposes. They provide a consistent interface across different operating systems, even though the underlying system calls might differ. They handle low-level details like the exact calling convention for system calls on the current processor architecture. They provide error handling in a standard way. And they sometimes add functionality like buffering that improves performance.

Higher-level programming languages build additional layers on top of these C library wrappers. When you open a file in Python, the open() function in Python eventually calls the C library’s open() function, which makes the system call. But Python adds its own abstractions, like file objects with convenient methods and automatic resource cleanup.

This layering means that the system call interface is relatively stable and low-level, while higher-level interfaces can evolve independently. The kernel provides basic primitives through system calls, libraries build upon these primitives to provide richer functionality, and applications use these higher-level interfaces to accomplish their goals.

Understanding this layering also helps explain why library updates can sometimes improve program performance or fix bugs without changing the kernel. The library might implement better buffering strategies, fix errors in how it uses system calls, or take advantage of newer system calls while maintaining compatibility with older kernels.

It also explains why some operations that seem like they should require kernel involvement sometimes don’t. Much of the functionality in the C standard library, like string manipulation or mathematical functions, is implemented entirely in user space without any system calls. Only when the library needs to interact with the outside world does it drop down to system calls.

Debugging and Tracing System Calls

When programs misbehave or perform poorly, examining their system call activity can provide valuable insights. Operating systems provide tools for tracing system calls, and understanding how to use these tools is valuable for both debugging and learning.

On Linux, the strace command allows you to see every system call a program makes. Running strace followed by a program name shows a detailed trace of all system calls, their parameters, and their return values. This can reveal what a program is actually doing at a low level, which is often enlightening.

For example, stracing a simple program that prints “Hello, World!” reveals that it makes many system calls beyond just printing the text. It might map libraries into memory, check for configuration files, initialize various subsystems, and finally write the actual output. Seeing all this activity helps you understand what’s really happening when even simple programs run.

System call traces can help diagnose performance problems. If a program is slow, examining its system calls might reveal that it’s making thousands of unnecessary calls, or using inefficient I/O patterns like reading one byte at a time without buffering. The trace shows exactly what system calls are being made and how much time each takes, pointing directly to inefficiencies.

They’re also valuable for understanding how programs work when you don’t have source code. By examining system calls, you can infer what a program is doing, what files it accesses, what network connections it makes, and so on.

On macOS, dtruss serves a similar purpose, and Windows has tools like Process Monitor that show system API calls. While the specific tools differ, the concept is the same: observing the program’s interactions with the operating system to understand and debug its behavior.

Security researchers use system call tracing to analyze potentially malicious software, seeing exactly what the program is trying to do without having to fully understand its code. System administrators use it to troubleshoot misbehaving programs or to understand resource usage patterns.

Learning to read system call traces is a valuable skill. It deepens your understanding of how programs interact with the operating system and provides a powerful debugging and analysis tool.

The Evolution of System Calls

System calls have evolved significantly since the early days of computing, and understanding this evolution provides perspective on current designs and future directions.

Early operating systems had relatively few system calls providing basic services. As operating systems grew more sophisticated, they added more system calls for new functionality. This created a tension: more system calls means more capabilities but also a larger interface to maintain compatibility with and potentially more complexity.

Some systems have tried to minimize the number of system calls by making them more general. The Plan 9 operating system, for example, famously made everything look like a file, allowing many operations to be performed through a small set of file-related system calls rather than needing specialized calls for different types of resources.

Other systems have grown larger system call interfaces over time to support new features efficiently. Linux has added hundreds of system calls over its lifetime, each providing specific functionality that was needed for performance or new capabilities.

The design of system call interfaces has also evolved. Early systems might have had very simple parameter passing conventions. Modern systems support much richer parameter types, including complex data structures passed between user space and kernel space.

Error handling conventions have evolved too. Modern system calls use well-defined error return mechanisms and provide detailed error codes that help programs understand what went wrong and potentially recover gracefully.

The rise of virtualization and containers has influenced system call design. Some newer system calls are specifically designed to support these technologies, allowing programs to create isolated environments or manage virtualized resources.

Security concerns have driven evolution as well. Newer system calls often include additional parameters for fine-grained permission control or support for security frameworks like capabilities or mandatory access control.

Looking forward, system call interfaces will continue to evolve to support new hardware, new use cases, and new programming models. However, the fundamental concept of system calls as controlled transitions between user space and kernel space for accessing privileged resources will likely remain central to operating system design.

System Calls and Operating System Design Philosophy

The design of a system call interface reflects fundamental choices about operating system philosophy and goals. Understanding these design decisions provides insight into why different operating systems work the way they do.

The Unix philosophy of providing simple, composable tools is reflected in its system call design. Unix system calls tend to be relatively simple primitives that can be combined in flexible ways. Rather than providing a complex system call that does many things, Unix provides simpler calls that each do one thing well, and programmers combine them to accomplish complex tasks.

This approach has advantages and disadvantages. It provides flexibility and keeps individual system calls simpler and easier to understand and implement correctly. However, it can mean more system calls are needed for complex operations, potentially affecting performance.

Windows takes a somewhat different approach, providing more comprehensive system calls that handle more complex scenarios directly. This can be more efficient for common cases but might be less flexible for unusual combinations of requirements.

The decision about what functionality belongs in the kernel versus user space also affects system call design. A microkernel philosophy, where minimal functionality is in the kernel and most services run in user space, leads to different system calls than a monolithic kernel where more functionality is built into the kernel itself.

Performance considerations influence design too. System calls that are expected to be called very frequently might be optimized differently than rare calls. Some systems provide both simple and complex versions of operations, letting programmers choose between ease of use and maximum performance.

Compatibility requirements shape system call evolution. Operating systems must typically maintain compatibility with existing programs, meaning old system calls can’t easily be removed or changed in incompatible ways. This leads to accumulation of legacy system calls and sometimes awkward designs where better approaches exist but can’t replace the old ones.

The design of system call interfaces represents a balance between many competing concerns: performance, security, flexibility, simplicity, compatibility, and functionality. Different operating systems strike this balance differently based on their goals and history.

Conclusion: The Essential Bridge

System calls represent one of the most fundamental concepts in operating system design and computer science more broadly. They solve the essential problem of how unprivileged user programs can access privileged resources and services in a controlled, secure manner.

We’ve explored how system calls work at a technical level, involving carefully orchestrated transitions between user mode and kernel mode, parameter passing, privilege checking, and result returning. We’ve seen the wide variety of services operating systems provide through system calls, from file operations to networking to process management. We’ve examined real examples of how programs use system calls and understood the performance implications that make system call frequency an important consideration.

The security aspects of system calls highlight their role as enforcement points for access control and isolation. The evolution and variation of system call interfaces across different operating systems demonstrates how this fundamental mechanism can be implemented in different ways while serving similar purposes.

For programmers, understanding system calls provides insight into what’s really happening when your programs interact with files, networks, or other programs. It explains performance characteristics, helps with debugging, and informs better design decisions.

For students of computer science, system calls exemplify key concepts like abstraction, protection boundaries, privilege levels, and interface design. They’re where the abstract world of algorithms and data structures meets the concrete reality of hardware and resources.

The next time you save a file, send a message, or run a program, remember that beneath the surface, a carefully designed dance of system calls is happening. Your program is politely asking the operating system for help, following precise protocols, crossing privilege boundaries safely, and receiving services that make modern computing possible. System calls are the essential bridge between what programs want to do and what the operating system allows them to do, and understanding this bridge is fundamental to understanding how computers actually work.