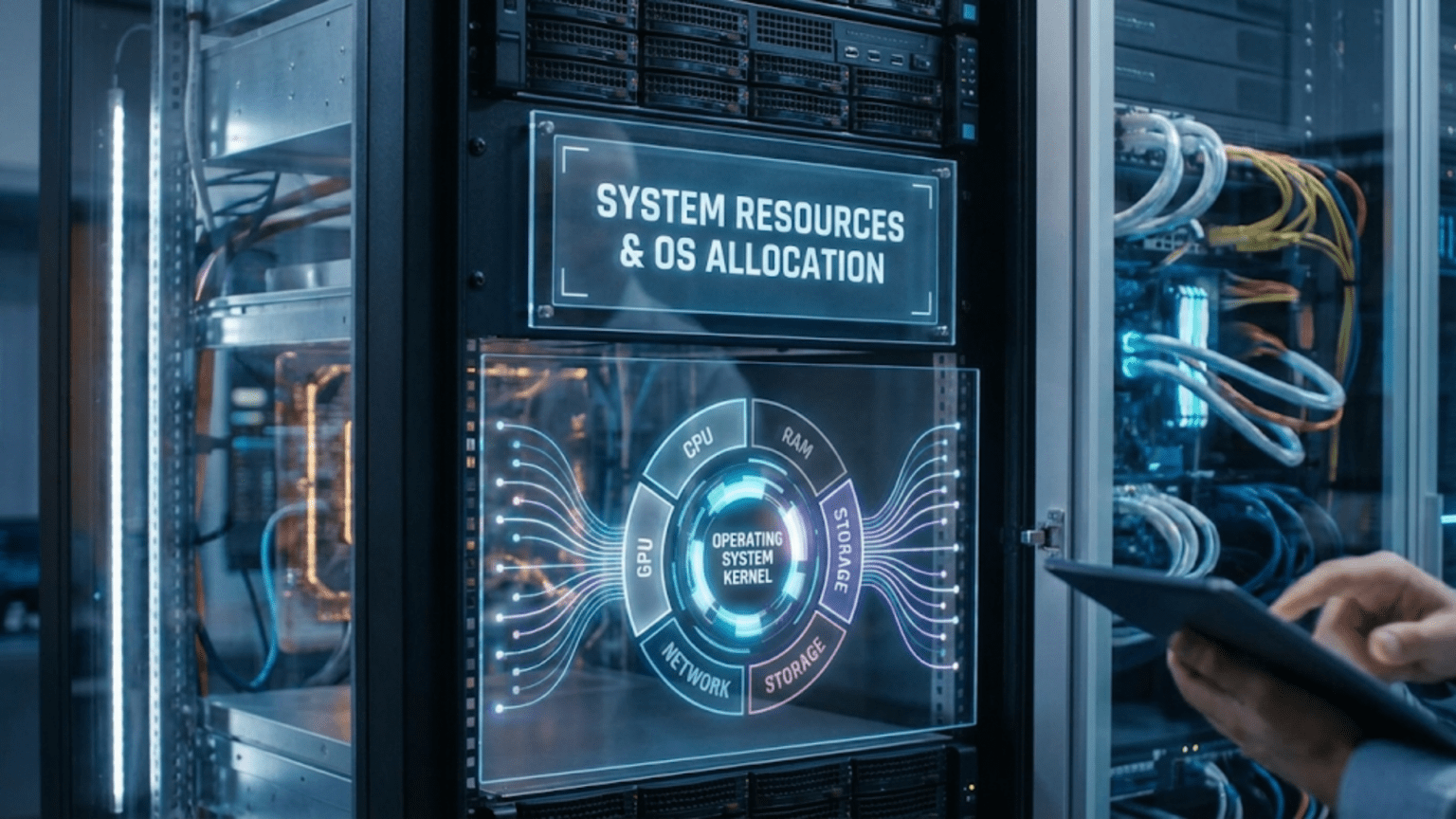

The Finite Ingredients Your Computer Must Share

Imagine you are hosting a dinner party where ten guests arrive but you only have enough ingredients to properly serve six people. You must carefully divide what you have so everyone gets something to eat, even if portions are smaller than you would prefer. Your computer faces a similar challenge every moment it runs. Multiple programs all want processor time, memory space, disk access, and network bandwidth, but these resources are limited. Your operating system serves as the wise host that divides these finite resources among all the programs competing for them, trying to ensure everyone gets what they need while preventing any single program from monopolizing resources that others require. Understanding what system resources are and how operating systems allocate them reveals the sophisticated resource management that makes modern multitasking computing possible.

System resources represent the physical and logical components that programs need to accomplish their work. Every program requires some amount of processor time to execute its instructions. Most programs need memory to store the data they are working with. Programs that read or write files need access to storage devices. Programs that communicate over networks need bandwidth. Programs that display graphics need access to the display hardware. The operating system must track all these resources, understand what is available and what is already allocated, and make decisions about who gets access to what and when. This resource management happens continuously in the background, invisible to users but absolutely essential for keeping your computer functioning smoothly when running multiple programs simultaneously.

The challenge of resource allocation lies in balancing competing goals that often conflict with each other. The operating system wants to maximize efficiency by keeping resources busy doing useful work rather than sitting idle. It wants to provide good responsiveness so interactive programs feel snappy when you click buttons or type. It wants fairness so all programs get reasonable access to resources rather than some being starved while others feast. It wants to prevent resource exhaustion where one greedy program consumes everything and makes the system unusable. Achieving all these goals simultaneously is impossible, so operating systems make trade-offs based on priorities, usage patterns, and design philosophies that reflect what the system designers considered most important.

The Major System Resources: What Programs Need to Run

Understanding what system resources exist and what makes each one valuable helps explain why resource management matters and what the operating system must coordinate.

Processor time represents the most fundamental resource because every program accomplishes work by executing instructions on the processor. When you have four processor cores and twenty programs running, those twenty programs must somehow share the four cores. The operating system’s scheduler divides processor time into small slices, typically just a few milliseconds long, and rapidly switches between programs so each gets regular turns at executing. This time-slicing happens so quickly that it creates the illusion all programs run simultaneously even though at any instant only four can actually be executing on the four cores. The processor is valuable because it is the engine that makes everything happen, and programs that need intensive computation require substantial processor time to complete their work efficiently.

Memory, specifically random access memory or RAM, provides the workspace where programs store data they are actively using. When you open a document, its contents load into memory. When a program calculates results, intermediate values reside in memory. Every running program needs some memory for its code, its data structures, and its variables. The total memory needed by all running programs often exceeds the physical RAM installed in the computer, so the operating system must manage memory carefully to fit everyone’s needs into limited space. Virtual memory techniques extend apparent capacity by using disk space as overflow when RAM fills up, but accessing disk is thousands of times slower than accessing RAM, making physical memory precious and its allocation critical for performance.

Storage bandwidth refers to how quickly data can be read from or written to permanent storage like hard drives or solid-state drives. While storage capacity might be abundant with hundreds of gigabytes or terabytes available, the rate at which data can transfer is limited. Traditional hard drives can handle only one read or write operation at a time because their mechanical read heads must physically move between locations. Even fast SSDs have finite bandwidth that multiple programs must share. When several programs simultaneously try to read or write large files, they compete for storage bandwidth and the operating system must decide whose requests to service first and in what order to maximize overall efficiency while maintaining fairness.

Network bandwidth determines how much data can be transmitted or received over network connections. Your internet connection might be rated at one hundred megabits per second, but when multiple programs all use the network simultaneously, they must share that bandwidth. Streaming video, downloading files, browsing websites, video calls, and background updates all compete for the same network capacity. The operating system allocates network bandwidth among these competing uses, sometimes prioritizing time-sensitive traffic like video calls over less urgent transfers like software updates.

File handles and descriptors represent another finite resource that tracks open files, network connections, and other input/output resources. Operating systems limit how many files each program can have open simultaneously and how many total files can be open system-wide. These limits prevent programs from exhausting resources by opening thousands of files they never actually use. While less intuitive than physical resources like processor and memory, these logical resources are equally important because programs fail unpredictably when they cannot open files they need due to exhausted file handle limits.

Graphics processing resources have become increasingly important as programs use GPUs for rendering graphics, processing video, and even accelerating computations through GPU computing. Multiple programs might want to use the graphics card simultaneously for different purposes, and the operating system must coordinate access to ensure they do not conflict and that critical graphics operations like updating the display get priority over background GPU computations.

How the Operating System Tracks Resource Usage

Before the operating system can allocate resources effectively, it must understand what resources exist, what is currently available, and what each program is using. This tracking provides the information foundation for allocation decisions.

The operating system maintains detailed data structures recording resource state. For processor cores, it tracks which processes are running on which cores at any moment and which processes are ready to run but waiting for available cores. For memory, it maintains tables showing which memory pages are allocated to which processes, which pages are free, and which pages have been swapped to disk. For storage devices, it monitors pending read and write operations and tracks which processes have files open. This continuous monitoring creates a real-time picture of resource usage across the entire system.

Resource usage statistics accumulate over time, showing not just current state but also historical patterns. The operating system tracks how much processor time each process has consumed, allowing it to calculate CPU usage percentages. It monitors how much memory each process has allocated and whether that allocation is growing over time, potentially indicating memory leaks. It records how much data each process has read from or written to disk, revealing which programs perform heavy I/O. These statistics enable both the operating system’s allocation decisions and the system monitoring tools that show users what their programs are doing.

Accounting mechanisms charge resource usage to specific processes and users, enabling quota enforcement and resource limiting. On multi-user systems, administrators can set quotas limiting how much disk space each user can consume or how much processor time their processes can use over specific periods. The operating system tracks usage against these quotas and prevents operations that would exceed limits. Even on single-user systems, resource accounting helps identify which programs consume disproportionate resources and might benefit from optimization or termination.

Performance counters built into modern processors provide detailed measurements of low-level events like cache misses, branch mispredictions, or memory access patterns. The operating system can access these counters to understand not just how much processor time programs use but how efficiently they use it. Programs that generate many cache misses might achieve poor performance even with substantial allocated processor time, while programs with good cache behavior accomplish more with less time. These detailed metrics guide sophisticated allocation decisions beyond simple time measurements.

CPU Allocation: Time-Slicing and Scheduling

Processor time represents the most dynamically allocated resource, with the operating system making scheduling decisions thousands of times per second to divide processor cores among competing processes.

The scheduler determines which processes run on which processor cores at any moment based on complex policies that balance responsiveness, fairness, and efficiency. When more processes want to run than cores exist, the scheduler must choose who gets to execute and who must wait. These decisions happen continuously as processes finish their time slices, block waiting for input or output, or new processes become ready to run. The constant adjustment ensures processor cores stay busy with useful work while all processes receive reasonable access.

Priority levels influence scheduling decisions by indicating that some processes are more important than others. Interactive programs that users directly work with typically receive higher priority than background tasks because delays in interactive programs are immediately noticeable and frustrating. System processes that keep the computer functioning get high priorities ensuring they are never starved for processor time by user applications. Background tasks like indexing files for search or running scheduled maintenance receive lower priorities so they proceed when processor cycles are available but do not interfere with more important work.

Time quantum sizes determine how long each process runs before the scheduler switches to another process. Longer quantums reduce the overhead of switching between processes but make the system less responsive because processes must wait longer for their turns. Shorter quantums improve responsiveness but waste more time on switching overhead. Most operating systems use quantums of ten to twenty milliseconds, balancing these competing concerns. The scheduler might adjust quantum sizes dynamically, giving interactive processes shorter quantums for better responsiveness while giving computational processes longer quantums to reduce switching overhead for work that does not need immediate response.

Multi-level queue scheduling organizes processes into different priority classes that receive different treatment. One queue might hold interactive processes that get frequent short time slices, another might hold batch processing jobs that get longer slices but run only when higher-priority queues are empty, and system processes might have their own queue with guaranteed processor access. Processes might move between queues based on their behavior—a process that consumes entire time slices repeatedly is probably computational and moves to lower-priority queues, while processes that frequently yield before time slices expire are probably interactive and remain in high-priority queues.

Load balancing on multi-core systems distributes work across all available processor cores to prevent some cores from being overloaded while others sit idle. When processes become ready to run, the scheduler preferentially assigns them to cores with lighter loads. When imbalances develop, the scheduler might migrate processes from busy cores to idle ones. However, migration has costs because the migrated process’s data is cached on its original core and moving it disrupts that cache, so the scheduler balances load distribution against cache efficiency.

Memory Allocation: Managing Limited RAM

Memory represents a finite resource that the operating system must carefully allocate to ensure all running programs fit within available RAM while maintaining good performance.

The memory allocator responds to requests from programs that need memory for their data structures and working storage. When a program asks for memory, the allocator finds available space and marks it as allocated to that program. The allocator tracks which memory regions are in use by which programs and which regions are free, using this information to satisfy allocation requests efficiently. Different allocators use different strategies for finding free memory—some search for the first available space large enough, others search for the smallest sufficient space to minimize wasted gaps, and some maintain separate pools for different allocation sizes.

Virtual memory extends apparent memory capacity beyond physical RAM by using disk space as overflow storage. The operating system divides memory into fixed-size pages, typically four kilobytes each, and can move pages between physical RAM and disk storage transparently as needed. Active pages that programs are currently using stay in RAM for fast access. Inactive pages that have not been accessed recently can be written to disk to free RAM for other uses. This paging happens automatically based on usage patterns, with the operating system tracking which pages have been accessed and preferentially keeping frequently used pages in fast RAM.

Page replacement algorithms determine which pages to move to disk when RAM fills up and space is needed for new allocations. The operating system wants to evict pages that will not be needed soon so their absence does not cause frequent page faults that force reading them back from slow disk. Least Recently Used strategies evict pages that have not been accessed recently, based on the principle that recently used pages are likely to be used again soon while long-unused pages are good eviction candidates. More sophisticated algorithms consider both how recently and how frequently pages have been accessed, recognizing that pages accessed once long ago are better eviction candidates than pages accessed repeatedly until recently.

Memory pressure indicators show whether the system has adequate free memory or is struggling to fit everything in RAM. Low memory pressure means plenty of free memory exists and allocations succeed quickly without paging. High memory pressure means little free memory remains and the system increasingly relies on paging to disk, degrading performance substantially. The operating system monitors memory pressure continuously and might take corrective actions like asking programs to release cached data they do not strictly need or warning users that memory is running low and closing programs would improve performance.

Working set management attempts to keep each program’s frequently accessed pages in RAM while allowing infrequently accessed pages to be paged out. The working set represents the pages a program has touched recently and is likely to need again soon. If a program’s working set fits comfortably in its allocated RAM, it runs efficiently with few page faults. If the working set exceeds allocated RAM, the program constantly faults on recently used pages, a condition called thrashing where it spends more time paging than executing useful instructions. The operating system monitors working set sizes and can adjust allocations, giving more RAM to programs that are thrashing and potentially reducing allocations to programs with excess memory.

Storage I/O Allocation: Scheduling Disk Access

Storage bandwidth allocation determines whose read and write operations are serviced when and in what order, critically affecting both throughput and responsiveness for programs that access files.

The I/O scheduler queues requests from multiple programs and decides which to service next based on algorithms that consider fairness, performance, and priorities. First-Come-First-Served scheduling handles requests in arrival order, providing perfect fairness but potentially poor performance when requests jump randomly across the disk requiring excessive mechanical movement in traditional hard drives. Deadline scheduling ensures requests are serviced before specified deadlines expire, preventing starvation where unlucky requests wait indefinitely while others are prioritized.

Elevator algorithms optimize hard drive performance by servicing requests in ways that minimize mechanical head movement. Rather than thrashing back and forth across the disk serving requests in arrival order, the elevator sweeps across the disk in one direction serving all requests along the way before reversing direction. This batching of nearby requests dramatically improves throughput compared to random access patterns. Modern drives with Native Command Queuing implement similar optimizations internally, reordering operations based on physical layout knowledge that the operating system lacks.

Solid-state drive scheduling differs from rotational disk scheduling because SSDs have no mechanical movement and all locations are equally fast to access. This eliminates the optimization opportunities that elevator algorithms exploit, so SSD schedulers focus instead on fairness, priority management, and allowing the SSD’s internal parallelism to operate effectively. The simpler scheduling reflects that much optimization has moved inside the SSD where its controller handles it based on internal architecture the operating system cannot see.

I/O priorities allow distinguishing time-critical operations from background activities. User interactions that read or write files might receive high priority ensuring responsive behavior, while background tasks like indexing or backups receive lower priority so they do not interfere with interactive work. The scheduler services high-priority requests preferentially, deferring low-priority operations until high-priority queues empty or allowing low-priority operations to proceed only when the storage device would otherwise be idle.

Read-ahead and write-back caching reduce actual I/O frequency by buffering data in memory. When a program reads a file sequentially, the operating system anticipates future reads and speculatively loads subsequent data before explicit requests arrive. When that data is requested, it is already in cache and available instantly. Similarly, write operations accumulate in cache rather than immediately writing to disk, allowing the operating system to coalesce multiple writes to the same location into single physical writes. This caching trades memory space for reduced I/O frequency, dramatically improving performance for programs with good access patterns while increasing complexity for ensuring data safety when writes are deferred.

Network Bandwidth Allocation

Network resources must be shared among programs using network connections for various purposes with different urgency and bandwidth requirements.

Traffic shaping controls how much bandwidth each program or connection can use, preventing any single transfer from monopolizing network capacity. The operating system can impose rate limits that cap maximum transmission rates for specific programs or connection types. This ensures that large downloads do not consume all available bandwidth and prevent other programs from accessing the network. Traffic shaping is particularly important on slower connections where bandwidth is scarce and must be carefully rationed among competing uses.

Quality of Service mechanisms prioritize certain network traffic based on application requirements. Real-time video calls need consistent low latency to avoid disruptions, while file transfers can tolerate delays and rate variations. QoS policies identify traffic types and allocate bandwidth accordingly, giving preferential treatment to latency-sensitive interactive traffic while allowing bulk transfers to use available bandwidth without impacting interactive performance. The operating system marks packets with priority indicators that both local scheduling and network equipment use to provide differentiated service.

Connection limiting prevents individual programs from opening excessive network connections that would exhaust system resources. Each network connection consumes memory for buffers and system data structures tracking connection state. Operating systems impose limits on simultaneous connections per program and total system-wide connections. These limits prevent poorly designed or malicious software from overwhelming the system with connection requests.

Bandwidth monitoring tracks network usage per application, enabling users to understand what consumes their bandwidth and identify unexpected usage that might indicate problems. The operating system records how much data each program transmits and receives, exposing this information through system monitoring tools. This visibility helps diagnose performance issues and manage metered connections where exceeding data caps incurs costs.

Resource Limits and Quotas: Preventing Overconsumption

Operating systems impose various limits that prevent individual programs or users from consuming excessive resources that would affect others.

Per-process resource limits constrain how much of various resources each program can use. Memory limits cap maximum memory allocation, preventing runaway memory consumption from exhausting all RAM. CPU time limits restrict how long programs can execute, useful for preventing infinite loops or computationally intensive tasks from monopolizing processors indefinitely. File descriptor limits cap how many files programs can have open simultaneously. These limits protect system stability by ensuring no single program can exhaust resources completely.

User quotas limit total resources a user account can consume, particularly important on multi-user systems where multiple people share the same computer. Disk quotas prevent users from filling all storage space, ensuring room remains for other users and system operations. Process count limits prevent users from launching excessive numbers of programs. These quotas ensure fair sharing of system resources among multiple users.

Cgroups on Linux provide sophisticated resource management by organizing related processes into groups that share resource allocations. A container might be assigned specific amounts of CPU time, memory, and I/O bandwidth, with all processes in that container collectively sharing those allocations. This enables isolating different workloads or tenants on shared systems, preventing one from affecting others by consuming excessive resources.

Resource reservation allows critical programs to guarantee they will receive needed resources even under heavy load. A database server might reserve specific amounts of memory and processor time ensuring it remains responsive even when other programs compete heavily for resources. While reducing flexibility, reservations provide performance guarantees that are sometimes essential for meeting service level requirements.

Understanding system resources and their allocation reveals the sophisticated resource management that enables modern multitasking computing. The operating system continuously tracks what resources exist, what each program is using, and what remains available, making thousands of allocation decisions per second to divide finite resources fairly and efficiently among competing demands. This invisible orchestration ensures your computer remains responsive even when running many programs simultaneously, prevents any single program from monopolizing resources others need, and maximizes overall system utilization. The next time you have multiple programs running smoothly, appreciate the complex resource management working behind the scenes to make that possible despite limited processor cores, memory capacity, and I/O bandwidth being shared among all those competing programs.