The Essential Software That Bridges Operating Systems and Hardware

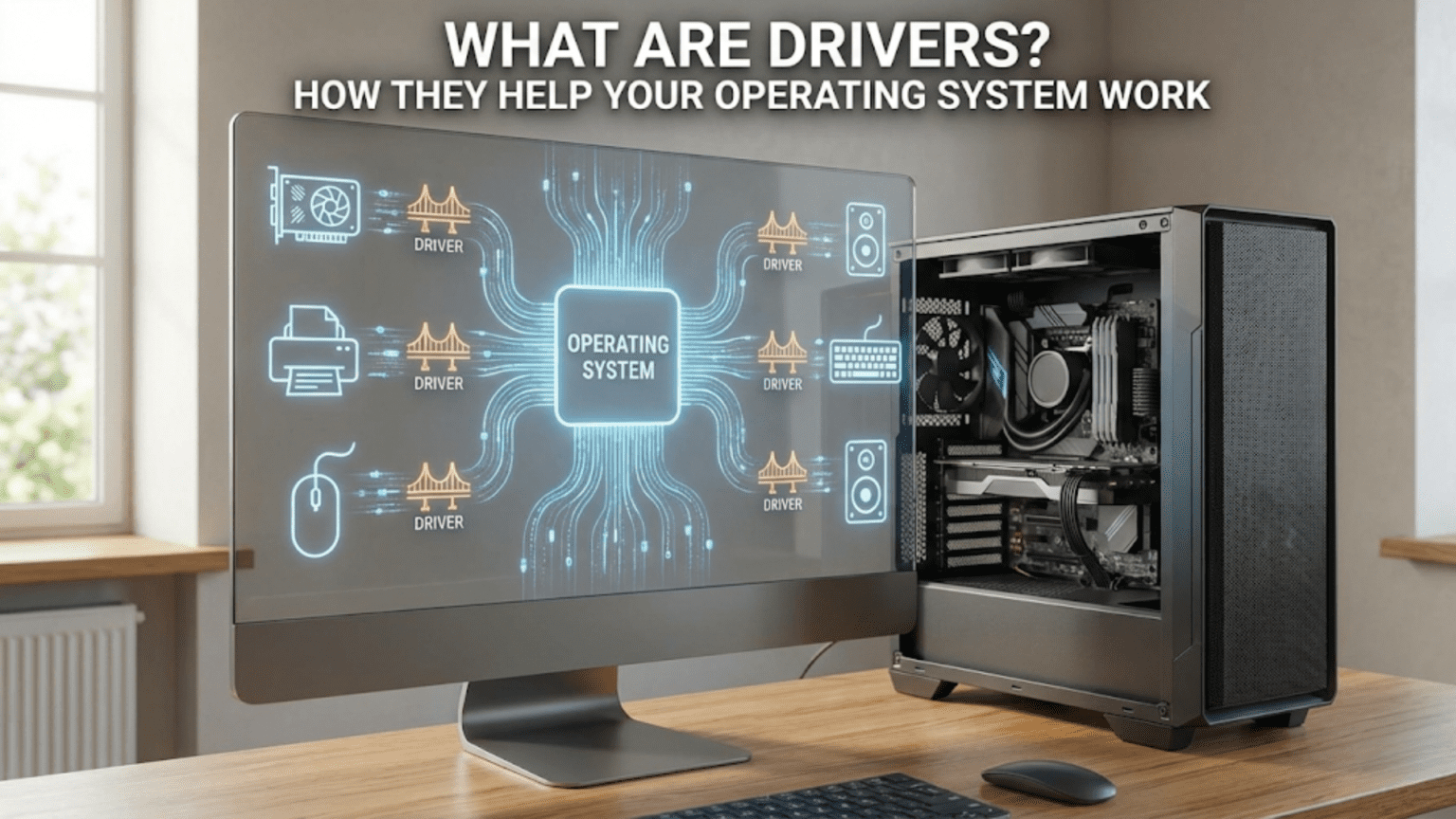

When you plug a printer into your computer and it immediately starts working, when you connect a game controller and it responds to your inputs, or when you install a new graphics card and it displays beautiful images on your monitor, you’re witnessing the work of device drivers. These specialized pieces of software operate behind the scenes, translating between the operating system’s generic commands and the specific language that each hardware device understands. Without drivers, your operating system would be unable to communicate with the vast ecosystem of hardware devices that make modern computing possible.

Device drivers represent one of the most critical yet least understood components of computer systems. They exist in a middle layer between the operating system kernel and the physical hardware, serving as interpreters that allow these two very different worlds to communicate. The operating system knows how to manage processes, allocate memory, and coordinate activities, but it doesn’t know the intricate details of how your specific printer marks paper, how your particular graphics card draws pixels, or how your exact network adapter sends data over cables. Drivers provide this device-specific knowledge, implementing the unique protocols and procedures that each piece of hardware requires.

The complexity drivers handle is staggering. A graphics driver might contain hundreds of thousands of lines of code implementing sophisticated rendering pipelines, memory management, and hardware-specific optimizations. A printer driver understands the exact sequence of commands needed to make a specific printer model produce the document you want. A network driver knows how to configure your network card, handle packet transmission, and respond to various network conditions. All this complexity remains hidden from both the operating system and the applications you use, presenting a simplified, standardized interface that makes everything appear to “just work.”

Understanding drivers helps explain numerous computing phenomena: why you sometimes need to install software before hardware works, why driver updates can improve performance or fix bugs, why some hardware doesn’t work with certain operating systems, and why driver problems can cause system crashes. This knowledge empowers you to troubleshoot hardware issues, make informed decisions about driver updates, and appreciate the remarkable engineering that allows thousands of different hardware devices to work seamlessly with your operating system.

The Fundamental Role: Translation and Abstraction

At their core, drivers perform two essential functions: translation and abstraction. Translation means converting generic requests from the operating system into specific commands that hardware understands. Abstraction means presenting a simplified, standardized interface that hides hardware complexity from the rest of the system. These two functions work together to make diverse hardware appear uniform to software.

Consider what happens when an application wants to print a document. The application doesn’t know or care about printer mechanics—it just has data to output. The application calls operating system functions with a generic request: “print this data.” The operating system receives this request but doesn’t know the specifics of your printer model. It forwards the request to the printer driver, which does understand your specific printer’s capabilities and communication protocols.

The printer driver translates the generic print request into a series of commands specific to your printer. It might convert the document into a page description language like PostScript or PCL that your printer understands. It configures the printer’s settings—paper size, print quality, color mode—based on your preferences. It breaks the job into manageable pieces and sends them to the printer in the exact format and sequence the printer expects. It monitors the printer’s status, handling situations like out-of-paper conditions or error states. All of this happens transparently—the application and operating system don’t need to know these details.

This abstraction allows applications to work with any printer without being rewritten for each model. Word processors don’t contain code for thousands of different printers. Instead, they use standard operating system printing interfaces, and drivers handle the device-specific details. The same document can print on an inkjet, laser, or professional press without the application changing—only the driver differs. This separation of concerns makes software development practical and enables hardware manufacturers to create new devices that work with existing software.

The abstraction works both ways. Not only do drivers present standardized interfaces upward to the operating system, they also shield the OS from hardware complexity. A graphics card might have hundreds of programmable processing units, complex memory hierarchies, and intricate rendering pipelines. The graphics driver manages all this complexity, presenting the operating system with a simplified interface: “draw these pixels,” “allocate this texture memory,” “execute this shader program.” The operating system doesn’t need to understand GPU architecture—the driver handles it.

Different hardware categories use different standardized interfaces. Storage drivers conform to standards like SCSI or NVMe that define how operating systems communicate with storage devices. Network drivers implement interfaces defined by network protocol stacks. Graphics drivers use APIs like DirectX or Vulkan on Windows, or OpenGL on various platforms. These standardized interfaces allow operating systems to work with entire categories of devices through consistent interfaces, while drivers provide the device-specific implementation details.

Driver Architecture: Kernel Mode vs. User Mode

Drivers can execute in different privilege levels within the operating system, with important implications for performance, stability, and security. Understanding this architecture helps explain why driver problems can be so severe and why driver development requires special care.

Most traditional drivers run in kernel mode, the highly privileged processor mode where the operating system kernel itself executes. Kernel-mode code has unrestricted access to all system memory, can execute privileged processor instructions, and can directly manipulate hardware registers. This access is necessary because drivers must configure hardware, respond to hardware interrupts, and operate with minimal latency. When a network packet arrives, the network driver must handle it immediately—there’s no time for the overhead of switching between protection modes.

However, this privilege comes with significant risks. A bug in kernel-mode driver code can corrupt system memory, crash the entire operating system, or create security vulnerabilities. Unlike application crashes that affect only that application, kernel-mode crashes typically bring down the entire system in a “blue screen of death” or kernel panic. The driver runs with complete system access, so programming errors or malicious code can cause unlimited damage. This is why driver development requires expert knowledge and careful testing—mistakes have system-wide consequences.

Some modern operating systems support user-mode drivers for certain device categories. User-mode drivers run with the same restricted privileges as regular applications, unable to directly access hardware or kernel memory. The operating system mediates all hardware access, providing isolation that prevents driver bugs from crashing the system. If a user-mode driver fails, the operating system can restart it without affecting other components. This architecture dramatically improves system stability and security.

User-mode drivers work well for devices where latency isn’t critical and performance requirements are modest. Printers make excellent candidates—print jobs aren’t time-sensitive enough that the overhead of operating system mediation matters. USB devices, scanners, and various peripherals can use user-mode drivers successfully. Windows has increasingly moved drivers to user mode where possible, particularly for USB devices and printers, improving system reliability.

However, user-mode drivers aren’t suitable for all devices. High-performance devices like graphics cards and network adapters need the minimal latency and maximum performance that only kernel-mode drivers provide. The overhead of switching between user mode and kernel mode for every operation would be unacceptable. These devices continue using kernel-mode drivers, accepting the stability risks in exchange for necessary performance. The trade-off between safety and performance means that operating systems use a hybrid approach, with different driver types for different device categories.

The operating system provides frameworks that drivers build upon. Windows offers the Windows Driver Model (WDM) and later frameworks like KMDF (Kernel-Mode Driver Framework) and UMDF (User-Mode Driver Framework). Linux provides various driver frameworks for different device types. These frameworks handle common tasks—resource allocation, power management, plug-and-play support—allowing driver developers to focus on device-specific functionality rather than reimplementing standard infrastructure for each driver.

Driver Loading and Initialization

The process of loading and initializing drivers reveals how operating systems discover hardware and prepare it for use. Understanding this process helps explain why some devices work immediately while others require installation, and why driver loading problems can prevent hardware from functioning.

During system boot, the operating system performs hardware detection, identifying devices connected to the system. Modern systems use plug-and-play mechanisms that allow hardware to identify itself. Each device contains identifiers—vendor IDs, device IDs, class codes—that specify what it is. The operating system queries these identifiers and searches for matching drivers. If an appropriate driver is found, the system loads it and allows it to initialize the device.

For built-in drivers included with the operating system, this process happens automatically. Common devices like USB controllers, SATA controllers, and standard peripherals have inbox drivers shipped with the OS. The system detects these devices, loads the built-in drivers, and initializes them without user intervention. This is why basic USB ports, built-in network adapters, and display functionality typically work immediately after installing an operating system.

Third-party drivers require explicit installation before the operating system can use them. When you insert a CD with printer drivers or download graphics drivers from a manufacturer’s website, you’re adding driver files to the system’s driver store—a repository where the operating system looks for drivers during device detection. The installation process copies driver files to appropriate locations, registers the driver with the operating system, and may configure various settings. Once installed, the driver becomes available for the system to load when the corresponding hardware is detected.

Modern operating systems can automatically download drivers from the internet when new hardware is detected. Windows Update includes an enormous database of drivers for common devices. When you plug in a new device, Windows checks whether it has a suitable driver. If not, it can query Microsoft’s servers, download an appropriate driver, and install it automatically. This feature makes hardware installation much simpler than in earlier eras when every device required manual driver installation from manufacturer media.

Driver signing became a crucial security feature, particularly on 64-bit systems. Operating systems can require that drivers be digitally signed by trusted authorities, proving they come from legitimate sources and haven’t been tampered with. Windows enforces driver signing requirements on 64-bit systems, preventing unsigned kernel-mode drivers from loading. This prevents malware from installing malicious drivers that would have complete system access. Linux systems can enable similar mechanisms through secure boot and module signing.

When a driver loads, it goes through an initialization sequence. The driver registers itself with the operating system, informing the system what capabilities it provides. It probes for its associated hardware, verifying that the device is present and responding. It configures the device to a known initial state, resetting any previous configuration. It allocates system resources like memory buffers and interrupt handlers that it will need during operation. It may load firmware onto the device—some hardware contains programmable processors that require code to be uploaded before they can function.

If initialization fails at any point, the driver reports an error and the device won’t function. Common causes include hardware conflicts (two devices trying to use the same resources), firmware problems, corrupted driver files, or incompatible driver versions. The operating system typically logs these failures, providing information for troubleshooting. Device Manager on Windows or dmesg on Linux show these errors, helping diagnose why hardware isn’t working.

How Drivers Handle Hardware Communication

Once loaded and initialized, drivers spend most of their time facilitating communication between the operating system and hardware. This communication happens through several mechanisms, each suited to different situations and performance requirements.

Programmed I/O involves the processor directly reading from and writing to hardware registers—special addresses that correspond to device controls rather than memory. When a driver wants to send a command to hardware, it writes specific values to specific registers. The hardware interprets these register writes as commands and acts accordingly. The driver reads from registers to check device status, retrieve data, or monitor conditions. This method is straightforward but can be slow because the processor must be directly involved in every data transfer.

Interrupts provide a mechanism for hardware to notify the processor that it needs attention. When significant events occur—a network packet arrives, a disk read completes, a user presses a keyboard key—the hardware generates an interrupt. This electrical signal causes the processor to immediately suspend whatever it’s doing, save its current state, and jump to an interrupt handler—a function within the driver designed to respond to that specific interrupt. The handler deals with the event—perhaps retrieving arrived data, starting another operation, or notifying waiting processes—then returns control, allowing the processor to resume its previous work.

Interrupt handling must be extremely fast because interrupts suspend normal system operation. Drivers typically split interrupt handling into two parts: the interrupt service routine (ISR) that runs immediately when the interrupt occurs, and deferred procedure calls or bottom halves that run later. The ISR performs minimal urgent processing—acknowledge the interrupt, perhaps grab critical data—then schedules the deferred procedure to handle less time-critical tasks. This approach minimizes how long interrupts are blocked while still ensuring proper event handling.

Direct Memory Access (DMA) allows devices to transfer data to and from memory without processor involvement. The driver configures the DMA controller with source and destination addresses and the amount of data to transfer, then instructs the device to proceed. The device and DMA controller handle the actual transfer independently while the processor continues other work. When the transfer completes, the device generates an interrupt notifying the driver. DMA dramatically improves performance for bulk data transfers—network packets, disk blocks, audio streams—by offloading data movement from the processor.

Memory-mapped I/O presents device memory or registers as part of the system’s memory address space. Instead of special I/O instructions, the driver simply reads from and writes to memory addresses that correspond to device resources. A graphics driver might map the graphics card’s video memory into system address space, allowing it to update display buffers by writing to memory locations. This technique provides fast access and simplifies driver code by using standard memory access operations.

Command queues are sophisticated structures where the driver and hardware exchange commands and data through shared memory structures. The driver writes command descriptors to a queue, and the hardware processes them asynchronously. Similarly, the hardware writes completion notifications to queues that the driver checks. Modern high-performance devices like NVMe storage drives use command queues extensively, allowing multiple operations to be in flight simultaneously and enabling the device to optimize operation ordering for maximum performance.

Driver Updates: Why and How

Driver updates represent a common but often misunderstood aspect of system maintenance. Understanding why drivers need updates and how to manage them helps maintain system stability and performance.

Manufacturers release driver updates for several reasons. Bug fixes address problems discovered after initial release—crashes in specific situations, compatibility issues with certain software, or incorrect behavior under particular conditions. Performance improvements optimize code paths, implement better algorithms, or take advantage of hardware features that weren’t initially utilized. New feature support adds capabilities, perhaps enabling new operating system features or exposing additional hardware functionality. Security patches fix vulnerabilities that could be exploited to compromise system security.

Not all driver updates are equally important. Security updates should be installed promptly as they fix vulnerabilities that attackers might exploit. Stability updates that fix crashes or data corruption are also high priority. Performance updates and new features are less urgent—if your system works satisfactorily, these updates offer improvements rather than fixing critical problems. Sometimes newer drivers introduce new bugs, so if your system is stable, the cautious approach is to update only when necessary.

Windows Update handles many driver updates automatically, downloading and installing updated drivers without explicit user action. This convenience ensures most systems receive important driver updates, but it can occasionally cause problems if a new driver is buggy or incompatible with specific configurations. Windows allows you to postpone updates or roll back to previous driver versions if problems occur. Manufacturers also provide drivers directly from their websites, often offering newer versions than Windows Update supplies.

Linux systems handle drivers differently. Most drivers are part of the kernel itself, updated when you update the kernel. This integration means driver updates come through normal system update mechanisms. Some hardware requires proprietary drivers from manufacturers—particularly graphics cards and WiFi adapters—which must be installed separately. Linux distributions vary in how they handle these proprietary drivers, with some offering easy installation tools while others require manual intervention.

Graphics drivers deserve special mention because they’re among the most complex and frequently updated drivers. Gaming and professional graphics applications push hardware to its limits, and driver optimizations can significantly impact performance. Graphics manufacturers release drivers frequently, often optimizing for newly released games or applications. These updates may not be necessary for casual users but can be important for demanding workloads.

Rolling back to previous driver versions becomes necessary when new drivers cause problems. Windows Device Manager allows selecting and installing previous driver versions. Linux systems can downgrade packages to earlier versions. Keeping previous driver versions available provides an escape route if updates introduce issues. Some users prefer not updating drivers that are working correctly, accepting the trade-off between missing optimizations and maintaining stability.

Driver compatibility between operating system versions varies. Major OS updates may require new drivers—drivers written for Windows 10 might not work on Windows 11, or vice versa. Before upgrading your operating system, verify that updated drivers exist for your critical hardware. Manufacturers sometimes stop supporting older hardware, meaning drivers aren’t available for newer operating systems. This can be a significant factor in upgrade decisions, particularly for specialized or professional hardware.

Generic Drivers vs. Manufacturer-Specific Drivers

Operating systems include generic drivers that provide basic functionality for many devices, while manufacturers supply optimized drivers that unlock full capabilities. Understanding this distinction helps explain why installing manufacturer drivers sometimes improves performance or enables features.

Generic drivers implement standardized protocols that many similar devices share. The operating system includes generic USB storage drivers that work with any USB flash drive or external hard drive implementing standard protocols. Generic display drivers provide basic screen output for any graphics card. Generic network drivers handle basic Ethernet functionality. These inbox drivers ensure that hardware at least partially works without requiring third-party driver installation, providing a functional baseline.

However, generic drivers typically don’t support device-specific features or optimizations. A graphics card might have advanced 3D capabilities, hardware video encoding, or multiple monitor support that generic drivers don’t expose. A printer might support special paper sizes, quality settings, or duplex printing that generic drivers don’t offer. A network adapter might have advanced features like wake-on-LAN, traffic prioritization, or hardware offloads that generic drivers ignore.

Manufacturer-specific drivers are optimized for particular hardware models, implementing device-specific features and performance enhancements. These drivers may include control panels offering advanced settings not available through generic drivers. They might implement proprietary features, hardware acceleration, or manufacturer-specific APIs. They’re typically larger and more complex than generic drivers because they contain code for all the special capabilities their hardware provides.

The performance difference between generic and specific drivers varies dramatically by device type. Graphics cards show enormous differences—generic drivers provide basic display but no 3D acceleration, making gaming or professional graphics work impossible. High-end network adapters might perform significantly better with manufacturer drivers that implement hardware offloads and optimizations. Simple devices like keyboards or mice may show negligible differences since the generic drivers already provide complete functionality.

Some devices require manufacturer drivers to function at all. Advanced features like fingerprint readers, specialized input devices, or professional audio interfaces often need proprietary drivers since no generic equivalent exists. The hardware uses non-standard protocols or capabilities that generic drivers don’t support. For these devices, manufacturer driver installation is mandatory, not optional.

The Future of Driver Architecture

Driver architecture continues evolving to address changing hardware landscapes, security requirements, and performance needs. Understanding these trends provides insight into where computing is heading and how driver ecosystems are changing.

Driver standardization has increased, reducing the need for device-specific drivers in many categories. USB implements class specifications defining standard protocols for common device types—keyboards, mice, storage, audio—allowing operating systems to include generic drivers that work with any conforming device. This standardization is why you can plug in most USB devices and they work immediately without driver installation. Similar standardization exists for other device categories, gradually expanding the range of devices that work with inbox drivers.

Security has become a primary driver architecture concern. The traditional model of giving kernel-mode drivers unrestriced system access creates significant attack surface. Modern systems implement hardware-enforced security features, virtualization-based security, and tighter restrictions on what drivers can do. Windows 11 enforces stricter driver requirements, including mandatory code signing and driver isolation features. These changes improve security but require driver developers to adapt their practices.

User-mode driver frameworks continue expanding to cover more device categories. As operating systems improve user-mode driver performance and capabilities, more device types become suitable for user-mode implementation. This trend improves system stability by isolating driver bugs from the kernel, though performance-critical devices will likely always require kernel-mode drivers.

Open-source drivers have gained significant traction, particularly in the Linux ecosystem. Many hardware manufacturers now contribute open-source drivers to the Linux kernel, improving out-of-box hardware support. Some manufacturers provide reference driver implementations that the open-source community maintains. This approach benefits everyone—users get better hardware support, manufacturers avoid maintaining drivers across multiple kernel versions, and security researchers can audit driver code for vulnerabilities.

The rise of hardware virtualization and cloud computing has created new driver requirements. Paravirtualized drivers optimize virtual machine performance by using guest-aware protocols instead of emulating physical hardware. GPU passthrough and remote graphics protocols allow virtual machines to access graphics acceleration. These specialized drivers address scenarios that didn’t exist in traditional computing environments.

Drivers represent an essential but often invisible part of computing infrastructure. They enable the remarkable compatibility that allows thousands of different hardware devices to work with operating systems. They abstract hardware complexity, making software development practical. They handle the intricate details of hardware communication, ensuring that clicking “print” actually produces a document and plugging in a device makes it available for use. Understanding drivers helps demystify hardware functionality, explains common problems and their solutions, and reveals the sophisticated engineering that makes modern computing reliable and capable.