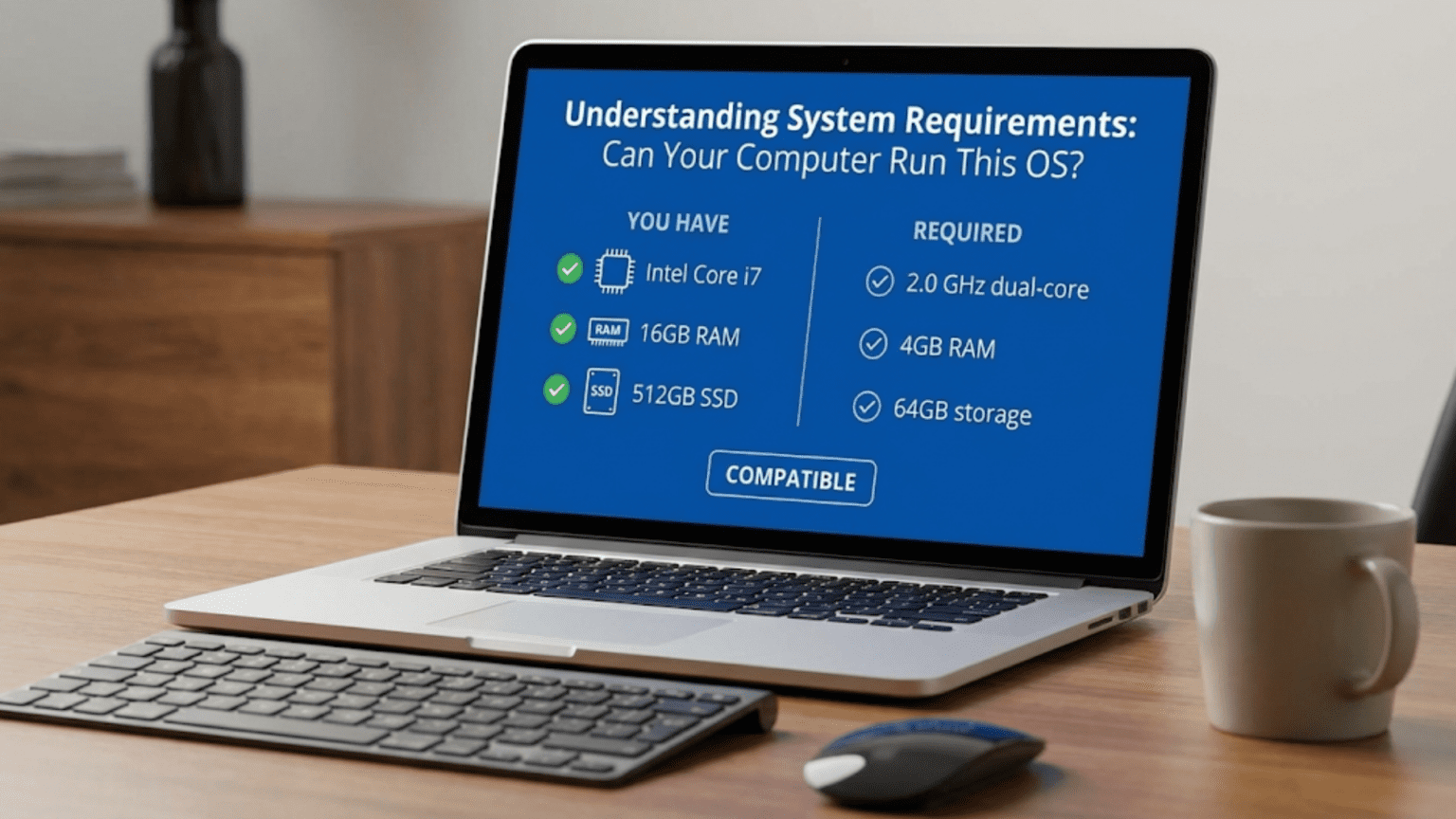

System requirements are the minimum and recommended hardware and software specifications needed to install and run an operating system effectively. These requirements specify necessary processor capabilities, RAM amounts, storage space, graphics capabilities, and other components, with minimum requirements representing the bare essentials for basic functionality while recommended requirements ensure smooth performance for typical usage scenarios.

Before installing a new operating system—whether upgrading Windows, switching to Linux, or trying macOS on supported hardware—you must determine whether your computer has sufficient resources to run it properly. System requirements serve as the operating system vendor’s specification of what hardware capabilities are needed, but understanding these requirements goes beyond simply reading a list of numbers. Minimum requirements might technically allow installation but result in frustratingly slow performance, while recommended requirements suggest configurations that provide acceptable user experiences. The difference between “can run” and “runs well” is significant, and knowing how to evaluate whether your specific computer meets, exceeds, or falls short of requirements helps you make informed decisions about operating system upgrades, new computer purchases, or whether to explore lighter-weight alternatives.

System requirements reflect the reality that operating systems are complex software with resource demands that vary based on features enabled, workloads running, and usage patterns. Modern operating systems include sophisticated graphical interfaces, security features, background services, and multitasking capabilities that all consume system resources. As operating systems evolve, adding new features and capabilities, their resource requirements typically increase—each new Windows version generally needs more powerful hardware than its predecessor, and the same applies to macOS and Linux desktop environments. Understanding system requirements allows you to predict performance, plan hardware upgrades, choose appropriate operating systems for older hardware, and avoid frustrating situations where technically compatible hardware provides unacceptably poor user experience. This comprehensive guide explores what system requirements mean, how to find and interpret them, how to check whether your computer meets requirements, what happens when requirements aren’t met, and how to make informed decisions about operating system compatibility with your hardware.

What System Requirements Include

Operating system requirements specify various hardware and software components necessary for installation and operation, each contributing to overall system performance and capability.

Processor or CPU requirements specify the minimum processor type, architecture, and speed. Modern requirements typically include processor architecture (x86-64/AMD64 for most Windows and Linux, ARM64 for newer Macs, 32-bit x86 for older systems), minimum processor generation or model (Windows 11 requires specific CPU generations with TPM 2.0 support), and sometimes minimum clock speed though this matters less than architecture and features. Processors have evolved significantly—a 2 GHz processor from 2005 performs very differently than a 2 GHz processor from 2025 due to architectural improvements, more cores, and enhanced instruction sets. Requirements might specify number of cores (dual-core minimum is common for modern desktop operating systems) or required processor features like hardware virtualization support, SSE2/AVX instruction sets, or specific security features.

Memory (RAM) requirements indicate how much random access memory the system needs. Minimum RAM represents the absolute lowest amount where the OS can boot and function, though often with poor performance due to excessive swapping to disk. Recommended RAM provides acceptable performance for typical usage. Modern operating systems have escalating memory requirements—Windows 11 officially requires 4GB minimum (8GB for 64-bit), many Linux distributions comfortably run with 2-4GB but recommend 8GB+, and macOS versions progressively increase requirements with each release. More RAM allows running more applications simultaneously, reduces disk swapping, improves responsiveness, and enables memory-intensive features like visual effects and search indexing.

Storage requirements specify both the type and amount of storage needed. Modern operating systems increasingly require or strongly recommend solid-state drives (SSDs) rather than traditional hard disk drives (HDDs) because SSDs provide dramatically faster random access speeds that significantly improve OS responsiveness. Storage space requirements include the space needed for OS installation itself plus working space for updates, temporary files, virtual memory paging files, and hibernation files. Windows 11 requires 64GB minimum storage, though practical usage requires significantly more. Linux distributions vary widely—minimal installations might need only 10-20GB while full desktop installations with applications might recommend 50GB+. macOS typically requires 35-40GB+ depending on version.

Graphics requirements specify display adapter capabilities. Basic requirements might just need any display adapter capable of driving the minimum resolution. Modern operating systems with hardware-accelerated graphics require DirectX-compatible (Windows), OpenGL/Vulkan-compatible (Linux), or Metal-compatible (macOS) graphics adapters with minimum feature levels. Specific features might require GPU acceleration—smooth visual effects, multiple displays, high-resolution displays, or advanced features like virtual desktops or transparency effects. Integrated graphics in modern processors typically meet basic requirements, while dedicated graphics cards provide better performance especially for gaming or creative work.

Display requirements specify minimum screen resolution and sometimes capabilities. Modern operating systems typically require minimum 1024×768 or 1280×720 resolution displays. Some features might require higher resolutions—Windows 11’s Snap Layouts work better at 1920×1080 or higher. Touch support, high DPI display support, or multi-monitor capabilities might have specific requirements.

Additional hardware requirements might include network connectivity (increasingly essential as operating systems integrate cloud features), audio output capability, input devices (keyboard and pointing device), optical drives (less common as installation moves to USB), and specific ports or interfaces. Some features have specific requirements—Windows Hello facial recognition requires an infrared camera, fingerprint login needs a fingerprint reader, and certain security features might require specific hardware modules like TPM (Trusted Platform Module).

Firmware requirements increasingly matter. UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) has largely replaced legacy BIOS, and modern operating systems might require UEFI with specific features like Secure Boot support. Windows 11 explicitly requires UEFI and Secure Boot enabled, marking a significant compatibility break from previous Windows versions.

Minimum vs. Recommended Requirements

Understanding the distinction between minimum and recommended requirements helps set realistic expectations about performance and usability.

Minimum requirements represent the absolute lowest specification where the operating system technically functions. A system meeting only minimum requirements can install and boot the OS, run basic applications, and perform fundamental operations, but the experience is often frustratingly slow. Minimum RAM might mean constant disk swapping where the system uses hard drive storage as extremely slow virtual memory, making every operation sluggish. Minimum storage might leave little room for applications, updates, or user files. Minimum processors might struggle with background tasks, causing interface lag and poor multitasking. Minimum graphics might disable visual effects, limit display resolution, or prevent using multiple monitors.

Operating system vendors set minimum requirements conservatively to maximize hardware compatibility and extend the lifespan of older computers, but these minimums rarely represent enjoyable user experiences. They serve purposes like allowing installation on point-of-sale terminals, embedded systems, or specialized devices where different usage patterns make low specifications acceptable, or enabling budget-conscious users to run current operating systems on older hardware with understanding that performance will be limited.

Recommended requirements suggest configurations that provide acceptable performance for typical users. A system meeting recommended specifications should handle everyday tasks—web browsing, email, document editing, media playback, casual multitasking—smoothly without frustrating delays. Recommended RAM allows running several applications simultaneously without swapping, recommended storage provides ample space for applications and files, and recommended processors handle typical workloads responsively. Recommended graphics enable visual effects and smooth rendering.

The gap between minimum and recommended can be substantial. Windows 10 technically runs on 1GB RAM (32-bit) minimum, but the recommended 4GB+ provides dramatically better experience. Many Linux distributions function with 1-2GB RAM minimum but recommend 4-8GB for desktop environments with full features. The recommendation tier aims for reasonably happy users rather than just functional systems.

Beyond recommended specifications, optimal or enthusiast configurations provide even better experiences. Power users, content creators, developers, or gamers might want configurations exceeding recommendations—16-32GB+ RAM for running many applications or virtual machines, fast NVMe SSDs for maximum responsiveness, powerful multi-core processors for compilation or rendering, and dedicated graphics cards for gaming or creative applications. These optimal specs aren’t required for basic OS operation but enable specific use cases or premium experiences.

Real-world performance depends not just on meeting requirements but on workload. Someone using their computer primarily for email and web browsing might find minimum requirements adequate, while someone running multiple applications, dozens of browser tabs, or memory-intensive software needs recommended or better specifications. Gaming, video editing, 3D modeling, software development, and other demanding workloads push hardware much harder than reading email.

How to Check Your Computer’s Specifications

Before determining whether your computer meets requirements, you must know what hardware you have.

On Windows, several built-in tools reveal system specifications. The System Information utility (run “msinfo32” from the Start menu or Run dialog) provides comprehensive hardware details including processor name and speed, installed RAM, BIOS/UEFI version, storage devices, graphics adapters, and more. The Settings app (System > About) shows basic information like processor, RAM, Windows edition, and system type (32-bit or 64-bit). The DirectX Diagnostic Tool (run “dxdiag”) specifically shows graphics and audio capabilities. Task Manager (Ctrl+Shift+Esc, Performance tab) displays real-time CPU, RAM, disk, and network usage plus hardware details. Windows PowerShell commands like “Get-ComputerInfo” or WMI queries provide scriptable access to detailed system information.

On macOS, the About This Mac dialog (Apple menu > About This Mac) shows processor type, memory, startup disk, and graphics. The System Information app (accessed via About This Mac > System Report or using Spotlight to find “System Information”) provides extensive details about all hardware components, installed software, and network configuration. The Activity Monitor (Applications > Utilities) shows real-time resource usage.

On Linux, various command-line tools reveal hardware information. “lscpu” shows detailed CPU information including architecture, cores, threads, and supported instruction sets. “lsmem” or “free -h” displays RAM amount and usage. “lsblk” or “df -h” shows storage devices and available space. “lspci” lists all PCI devices including graphics cards. “lshw” provides comprehensive hardware information (often requires sudo). Desktop environments typically include graphical system monitors showing hardware specs and resource usage.

Third-party utilities provide additional details or unified interfaces. CPU-Z (Windows) shows detailed processor, motherboard, and memory information. GPU-Z reveals graphics card details. Speccy or HWiNFO64 provide comprehensive system information. On Linux, hardinfo presents hardware information in a graphical interface.

Checking firmware type (BIOS vs. UEFI) matters for modern OS requirements. On Windows, System Information shows “BIOS Mode” (Legacy or UEFI). On Linux, checking for /sys/firmware/efi directory presence (it exists if booted with UEFI) or using “[ -d /sys/firmware/efi ] && echo UEFI || echo BIOS” command confirms firmware type.

Processor generation identification helps verify compatibility with generation-specific requirements. Processor names typically include model numbers—Intel Core i7-10700 indicates 10th generation, AMD Ryzen 5 5600X indicates 5000 series. Looking up specific model numbers online confirms exact specifications and generation.

Verifying TPM (Trusted Platform Module) presence matters for Windows 11 and some enterprise features. On Windows, run “tpm.msc” to open TPM Management console, which shows whether TPM is present and enabled. BIOS/UEFI settings also indicate TPM status.

Operating System Specific Requirements

Different operating systems have different requirements and philosophies about hardware support.

Windows 11 introduced controversial requirements that excluded many otherwise-capable computers. Official requirements include 64-bit processor with at least 1 GHz clock speed and 2+ cores (with specific processor generation requirements—8th gen Intel Core or 2nd gen AMD Ryzen minimum with exceptions), 4GB RAM, 64GB storage, UEFI firmware with Secure Boot capable, TPM 2.0, DirectX 12 compatible graphics with WDDM 2.0 driver, and 720p display. These requirements particularly the processor generation, TPM, and Secure Boot requirements, prevent installation on many computers that ran Windows 10 perfectly well. Microsoft positions these as security improvements (TPM enables hardware-based encryption, Secure Boot prevents rootkits) though the exclusion of capable hardware generated significant controversy.

Windows 10 has more accessible requirements: 1 GHz processor, 1GB RAM (32-bit) or 2GB RAM (64-bit), 16GB storage (32-bit) or 32GB (64-bit), DirectX 9 graphics with WDDM 1.0 driver, and 800×600 display. These lower requirements make Windows 10 viable on older hardware and remain relevant as Windows 10 continues receiving support until 2025.

macOS requirements are hardware-specific because Apple controls both hardware and software. Each macOS version explicitly lists compatible Mac models—macOS Sonoma supports Macs from 2018 or later (with specific exceptions), Ventura supports 2017+, etc. RAM requirements are typically 4GB minimum though 8GB+ recommended. Storage requirements increase with each version (generally 35-40GB+). Since macOS only runs on Apple hardware (officially), compatibility is about model year rather than generic specs, though unofficial patches enable running newer macOS versions on unsupported but capable Macs.

Linux distributions vary enormously in requirements based on desktop environment and included software. Lightweight distributions like Lubuntu, Puppy Linux, or antiX run comfortably on decade-old hardware with 512MB-1GB RAM and 10-20GB storage, making them excellent for reviving old computers. Standard desktop distributions like Ubuntu, Fedora, or Linux Mint recommend 2-4GB RAM minimum and 8GB+ for comfortable use, with 25-50GB storage. The choice of desktop environment dramatically affects requirements—lightweight environments like XFCE, LXQt, or LXDE use fraction of the memory and CPU of full-featured environments like GNOME or KDE Plasma.

Chrome OS (and its open-source basis ChromeOS Flex) has minimal requirements because most processing happens in cloud applications. Official ChromeOS Flex requirements include 64-bit Intel or AMD processor, 4GB RAM, and 16GB storage, making it viable on hardware where modern Windows would struggle. This cloud-centric approach reduces local processing demands.

What Happens When Requirements Aren’t Met

Running operating systems on hardware below requirements produces various problems depending on which requirements are unmet and by how much.

Insufficient RAM causes excessive paging or swapping—the OS constantly moves data between RAM and disk-based virtual memory. Because disks are thousands of times slower than RAM, excessive swapping makes the entire system sluggish. Applications take much longer to launch, switching between applications involves noticeable delays, and the system feels unresponsive overall. Hard drives show constant activity while the computer seemingly does nothing productive. With SSDs, swapping is less catastrophic than with traditional hard drives but still significantly impacts performance and reduces SSD lifespan through excessive writes.

Inadequate processor capability manifests as general slowness, interface lag, and poor multitasking. Moving windows, opening menus, or typing might exhibit noticeable delays. Background tasks (indexing, updates, antivirus scans) might consume resources to the point where foreground applications become unresponsive. Video playback might stutter or drop frames. Modern operating systems assume multi-core processors, so single-core CPUs struggle significantly.

Insufficient storage prevents installation entirely if available space is below minimum, or causes ongoing problems if space is marginally adequate. Updates might fail due to insufficient space for downloading and installing. The system can’t create temporary files needed for various operations. Performance degrades as the disk fills because the OS lacks space for virtual memory, temporary files, or caching. Some features automatically disable when storage is low.

Incompatible graphics hardware disables visual effects, limits resolution or refresh rates, prevents using multiple displays, or causes graphical glitches. Without proper graphics drivers, the OS might use basic fallback graphics with poor performance and limited capabilities. Some applications, particularly games or creative software, might refuse to run or crash frequently.

Missing firmware requirements might prevent installation entirely. Windows 11’s UEFI requirement means it won’t install on BIOS-only systems without workarounds. Secure Boot requirements can be blockers for systems with older firmware. TPM requirements prevent installation on otherwise-capable systems.

Architecture mismatches prevent installation—64-bit operating systems won’t install on 32-bit-only processors, and ARM operating systems won’t run on x86 processors (and vice versa) without emulation.

Workarounds exist for some incompatibilities. Windows 11’s strict requirements can be bypassed using registry modifications or modified installation media, though this removes official support and potentially security features. Older Macs can run newer macOS versions through OpenCore Legacy Patcher, accepting some feature limitations. Linux offers lightweight alternatives when standard distributions exceed hardware capabilities.

Making Informed Decisions About OS Compatibility

Understanding requirements helps make smart choices about operating systems and hardware.

Assessing current hardware against requirements involves comparing your specifications to both minimum and recommended tiers. If you exceed recommended requirements significantly, you can expect good performance. Meeting recommended puts you in the sweet spot for typical usage. Falling between minimum and recommended suggests marginal performance—usable but not pleasant, especially as the OS ages and future updates increase resource usage. Below minimum means serious problems or inability to install.

Planning for future needs matters because operating systems receive updates that gradually increase resource usage. The Windows 10 installation from 2015 used less RAM and storage than Windows 10 in 2023 after years of feature additions and updates. Buying or upgrading to just meet minimum requirements means falling below minimum within a year or two as updates accumulate. Targeting recommended or better provides longevity.

Considering use cases affects whether specifications are adequate. Light users (email, web browsing, document editing) can tolerate lower specifications than power users running multiple applications, virtual machines, or resource-intensive software. Gaming, video editing, 3D modeling, or software development demand much higher specifications than basic requirements suggest.

Choosing appropriate operating systems for hardware maximizes value from existing computers. An older laptop insufficient for Windows 11 might run Windows 10, Linux Mint, or ChromeOS Flex perfectly well, providing years more useful life. Lightweight Linux distributions revive ancient hardware for basic tasks. Specialized operating systems serve specific needs—FreeNAS for network storage, pfSense for routing/firewall.

Upgrading hardware strategically addresses bottlenecks. Adding RAM often provides the most noticeable improvement for underpowered systems—going from 4GB to 8GB or 16GB dramatically improves multitasking. Replacing hard drives with SSDs transforms system responsiveness more than processor upgrades in many cases. These targeted upgrades might make marginal systems adequate or good systems excellent.

Cost-benefit analysis guides upgrade vs. replace decisions. If your current hardware is close to requirements, a RAM and SSD upgrade might cost $100-200 and extend useful life several years. If it’s far below requirements, the same money might be better spent toward a new computer that comfortably exceeds requirements and provides longer future utility.

Practical Examples and Scenarios

Real-world scenarios illustrate how system requirements affect decision-making.

Scenario 1: Upgrading to Windows 11 on a 2017 computer. The computer has an Intel Core i5-7500 (7th generation), 8GB RAM, 256GB SSD, and UEFI firmware. It meets or exceeds most requirements (processor speed, RAM, storage, UEFI) but fails the processor generation requirement—Windows 11 officially requires 8th gen+. Options include staying on Windows 10 through 2025 support, using registry workarounds to bypass checks (losing official support), or upgrading to a new computer. Given good performance on Windows 10 and remaining support life, staying on Windows 10 might be most practical.

Scenario 2: Reviving a 2012 laptop for basic use. The laptop has an Intel Core i3-2310M, 4GB RAM, and a 500GB hard drive. It struggles with modern Windows 10, showing constant disk activity and slowness. Solutions include adding an SSD (the single biggest improvement), possibly upgrading RAM to 8GB if supported, or switching to lightweight Linux like Lubuntu or Linux Mint with XFCE desktop. The SSD upgrade alone might make Windows 10 tolerable, while Linux would run smoothly even on the existing hard drive.

Scenario 3: Choosing Linux for limited hardware. An older desktop with 2GB RAM and a single-core processor can’t run modern Windows acceptably. Lightweight Linux distributions like antiX, Puppy Linux, or Bodhi Linux specifically target such hardware, providing usable desktop environments where Windows would be unusable. This extends hardware utility without purchase.

Scenario 4: macOS upgrade compatibility. A 2015 MacBook Pro runs macOS Monterey (last supported version) but isn’t compatible with Ventura or Sonoma. The hardware (8GB RAM, dual-core i5, 256GB SSD) would technically handle newer macOS well, but Apple’s compatibility list excludes it. Options include staying on Monterey through security update period, using OpenCore Legacy Patcher to install unsupported macOS versions, or considering Linux as alternative for extended support.

Scenario 5: Building a new PC for Windows 11. When specifying a new computer, choosing 8th gen+ Intel or 2nd gen+ AMD processors, 16GB RAM, 512GB+ NVMe SSD, and ensuring UEFI with TPM 2.0 support guarantees Windows 11 compatibility with comfortable performance margin for future updates and typical workloads.

Conclusion

System requirements serve as essential guidelines for determining operating system compatibility, but understanding them requires looking beyond simple checklists to consider the difference between minimum specs and pleasant user experiences, the relationship between requirements and actual usage patterns, and how requirements evolve as operating systems receive updates over time. Meeting minimum requirements might allow installation but rarely provides satisfying performance, while exceeding recommended specifications ensures smooth operation now and provides headroom for future updates and increasing demands.

The process of evaluating system compatibility—checking your current hardware specifications, comparing them against requirements, considering your actual usage needs, and making informed decisions about upgrades, operating system choices, or new hardware purchases—empowers you to maximize value from existing equipment while avoiding frustrating experiences from underpowered configurations. Whether you’re deciding whether to upgrade Windows, exploring Linux as an alternative for older hardware, planning a new computer purchase, or troubleshooting poor performance on an existing system, understanding system requirements and their implications guides better decisions.

As operating systems continue evolving, requirements generally trend upward, reflecting both increasing feature sophistication and assumptions about available hardware. Yet this trend isn’t universal—the rise of lightweight Linux distributions, cloud-centric operating systems like Chrome OS, and renewed focus on efficiency in some projects provide options across the hardware capability spectrum. Modern computing offers operating system choices for nearly any hardware from decade-old laptops to cutting-edge workstations, but matching operating system to hardware appropriately determines whether your computing experience is frustrating or pleasant, whether your hardware investment is wasted or maximized, and whether you’re equipped for current needs and future growth.

Summary Table: Operating System Requirements Comparison

| Operating System | Minimum Processor | Minimum RAM | Minimum Storage | Recommended RAM | Recommended Storage | Special Requirements | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windows 11 | 1 GHz, 2+ cores, 64-bit (8th gen Intel or 2nd gen Ryzen+) | 4 GB | 64 GB | 8 GB | 128 GB+ | UEFI, Secure Boot, TPM 2.0, DirectX 12 GPU | Modern hardware (2018+), security-conscious users |

| Windows 10 | 1 GHz, 32-bit or 64-bit | 1 GB (32-bit)<br>2 GB (64-bit) | 16 GB (32-bit)<br>32 GB (64-bit) | 4-8 GB | 64 GB+ | DirectX 9 GPU | Broad hardware compatibility, older PCs |

| macOS Sonoma | Apple Silicon or Intel (2018+ models) | 4 GB | 35 GB+ | 8 GB | 50 GB+ | Specific Mac models only | Apple hardware 2018 or newer |

| Ubuntu Desktop | 2 GHz dual-core | 4 GB | 25 GB | 8 GB | 50 GB+ | 64-bit processor | General purpose, moderate hardware |

| Linux Mint | 1 GHz | 2 GB | 20 GB | 4 GB | 100 GB | 64-bit processor (recommended) | User-friendly Linux, moderate hardware |

| Fedora Workstation | 2 GHz dual-core | 2 GB | 20 GB | 4-8 GB | 40 GB+ | 64-bit processor | Current Linux features, modern hardware |

| Lubuntu (LXDE) | Pentium 4/Pentium M | 1 GB | 10 GB | 2 GB | 20 GB+ | PAE support | Older hardware revival |

| ChromeOS Flex | Intel/AMD x86-64 | 4 GB | 16 GB | 4 GB | 16 GB+ | UEFI compatible | Cloud-focused users, older laptops |

| antiX Linux | Intel Pentium III | 256 MB | 5 GB | 512 MB | 10 GB | i686 processor | Very old hardware, minimal resources |

Hardware Component Impact on Performance:

| Component | Insufficient Impact | Optimal Benefit | Upgrade Priority | Cost/Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAM | Excessive swapping, severe slowdowns, frequent freezes | Smooth multitasking, fast app switching, responsive system | High – Often the biggest bang for buck | Excellent – Usually $30-100 for significant improvement |

| Storage Type (SSD vs HDD) | Slow boot, slow app launches, general sluggishness | Fast boot (10-30 sec), instant app launches, snappy feel | Very High – Most noticeable improvement | Excellent – $50-150 transforms experience |

| Storage Capacity | Installation failure, update failures, can’t install apps | Room for programs, files, updates, peace of mind | Medium – Only if running out | Good – Needed when space constrained |

| Processor (CPU) | Interface lag, poor multitasking, slow processing | Smooth interface, good multitasking, fast computation | Low-Medium – Unless very old CPU | Fair – Expensive, often marginal benefit |

| Graphics (GPU) | Disabled effects, lower resolution, slow graphics | Smooth effects, high resolution, multiple displays, gaming | Low – Unless gaming/creative work | Variable – From free (integrated) to $1000+ |

| Display Resolution | Limited workspace, can’t use some features | More screen space, better readability, modern features | Low – Monitor upgrade needed | Good – If monitor is the constraint |

Quick Decision Guide:

| Your Situation | Recommended Action | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Exceed recommended specs | Proceed with upgrade/installation | Expect good performance, future-proof |

| Meet recommended specs | Proceed confidently | Optimal experience for typical use |

| Between minimum and recommended | Proceed with caution, consider usage | Usable but may feel slow, especially with updates |

| Meet only minimum specs | Consider alternatives or hardware upgrade | Technically works but likely frustrating |

| Below minimum specs | Use lighter OS or upgrade hardware | Won’t install or will perform very poorly |

| Specific requirement missing (TPM, UEFI, etc.) | Check for workarounds or alternative OS | May be hard blockers depending on requirement |