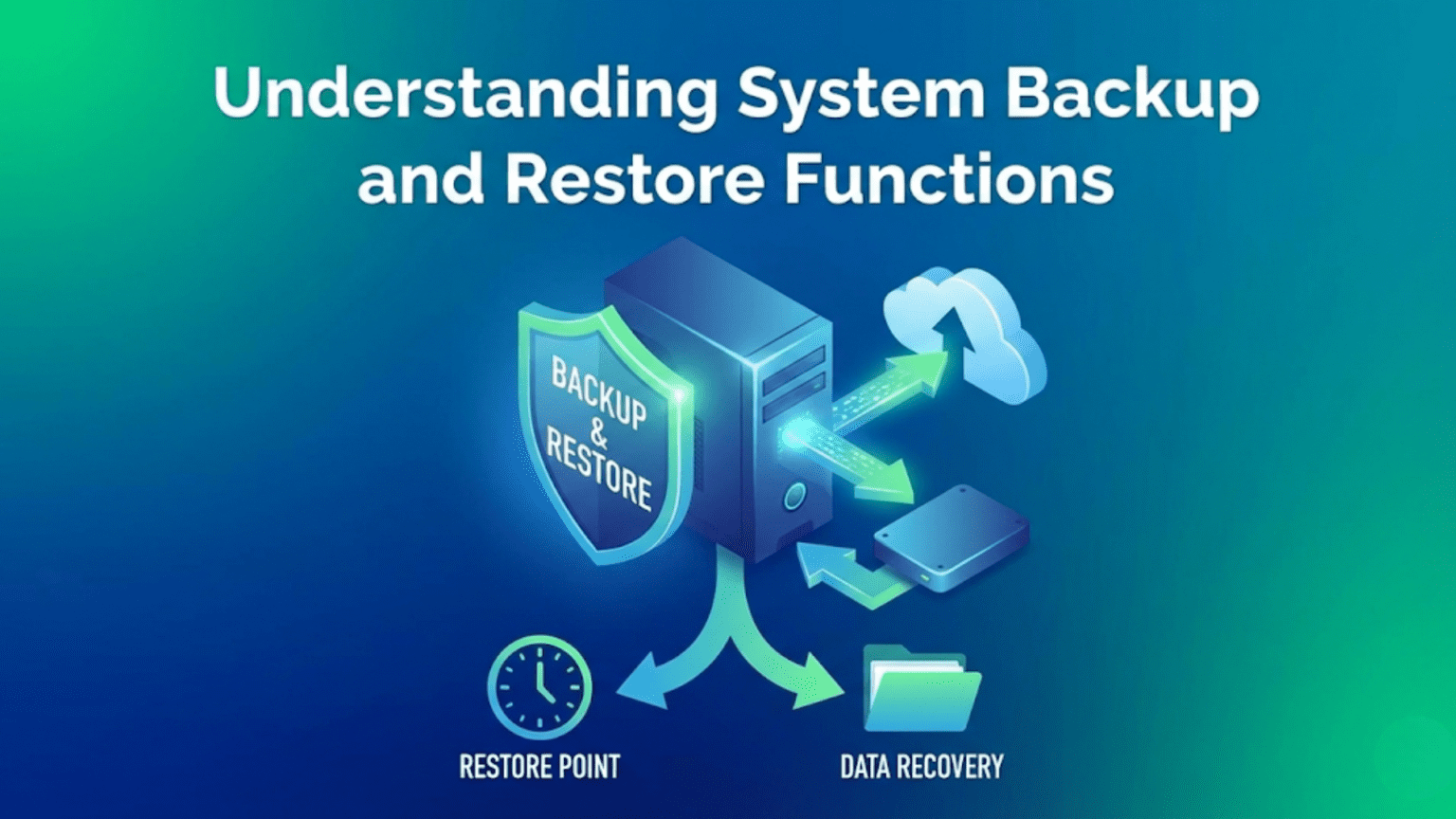

System backup and restore functions are built-in operating system features that create copies of data, system settings, and configurations at specific points in time, allowing users to recover from hardware failures, accidental deletion, software corruption, malware attacks, or other data loss events. Modern operating systems include multiple layers of backup protection—from file versioning that preserves previous versions of individual documents to full system images that capture the complete state of an entire operating system installation—providing comprehensive recovery options for different types of failures.

Data loss is one of the most devastating computing experiences a person can face. Whether caused by hardware failure, accidental deletion, ransomware encryption, software corruption, or natural disasters, losing important files, irreplaceable photos, critical work documents, or a carefully configured system represents hours, days, or even years of effort disappearing in an instant. This reality makes backup and restore functions among the most important features any operating system provides—yet they remain among the most underused until the moment they’re desperately needed. Understanding how operating systems implement backup and restore, what protection they provide automatically, what you must configure manually, and how to recover effectively when disaster strikes can mean the difference between a minor inconvenience and catastrophic, permanent loss.

Operating systems approach backup and restore through multiple complementary mechanisms, each protecting different aspects of your system at different granularities and frequencies. Automatic file versioning quietly saves previous versions of files as you work. System restore points capture system configuration snapshots before significant changes. Full system image backups preserve your entire operating system installation for complete recovery. Cloud synchronization continuously mirrors files to remote storage. Each mechanism serves different recovery scenarios—you wouldn’t use a full system image to recover a single accidentally deleted file any more than you’d use file versioning to recover from a hard drive failure. Understanding these mechanisms and when to use each provides comprehensive data protection that genuinely prevents catastrophic loss. This guide explores how backup and restore functions work across major operating systems, the different types of backup and what they protect, how to configure effective backup strategies, how to perform recoveries, and best practices that genuinely protect your data.

Why Backup and Restore Matters

The statistics around data loss are sobering. Studies consistently show that hard drives fail at rates of 3-5% annually, with failure rates increasing significantly after the first three years. Flash storage in SSDs has different failure modes but is equally vulnerable to unexpected failures. Ransomware attacks encrypt victims’ files and demand payment for decryption, with attacks affecting hundreds of millions of devices annually. Human error—accidental deletion, accidental overwrites, accidentally formatting drives—is statistically among the most common causes of data loss. Software bugs, operating system corruption, failed updates, and other software issues destroy data regularly. Natural disasters, theft, and hardware damage from spills or drops complete the threat landscape.

The 3-2-1 backup rule has become a standard recommendation in data protection: maintain at least 3 copies of data, on at least 2 different types of storage media, with at least 1 copy stored offsite (or in the cloud). This redundancy ensures that no single failure—hardware failure, theft, fire, ransomware—can destroy all copies simultaneously. Modern operating systems support creating these multiple backup layers, though they rarely implement all three automatically without user configuration.

Recovery time objectives and recovery point objectives matter practically. Recovery time objective (RTO) is how long you can afford to be without your data or system—can you wait 4 hours to restore from backup, or do you need to be back online in 15 minutes? Recovery point objective (RPO) is how much data loss is acceptable—can you lose one day’s work, or can you afford to lose only the last 5 minutes? These practical considerations determine what backup mechanisms you need: continuous real-time replication for near-zero RPO, versus nightly backups for acceptable daily loss scenarios.

The cost of not having backups extends beyond just lost files. Businesses lose productivity, revenue, and customer trust from data loss incidents. Personal users lose irreplaceable memories (photos, videos), years of creative work, or financial records. Even recoverable situations—data recovery services, ransomware negotiations—cost hundreds to thousands of dollars and often succeed only partially. By contrast, proper backup infrastructure costs little in time and money while providing comprehensive protection.

Types of Backup and What They Protect

Different backup types serve different purposes and offer different tradeoffs between storage requirements, recovery speed, and granularity of protection.

Full backups copy every file and piece of data in the backup scope—every document, photo, application, operating system file, and setting. Full backups are the most complete form of protection but require the most storage space and longest time to create. A full system image of a 250GB installation requires 250GB of backup storage. Despite storage requirements, full backups provide the simplest recovery—restoring from a full backup requires only that single backup without depending on previous backups.

Incremental backups copy only data that has changed since the last backup of any type. After an initial full backup, each incremental backup contains only new and modified files. This dramatically reduces backup size and time—if only 1% of files changed today, the incremental backup is only 1% the size of a full backup. The tradeoff is recovery complexity: restoring requires the original full backup plus every incremental backup in sequence. If one incremental backup is corrupted, the restore chain breaks.

Differential backups copy all data changed since the last full backup. Unlike incrementals that build on each previous backup, differentials always start fresh from the last full backup. Each differential grows larger as more time passes since the full backup (because it includes all changes since that full backup, not just since the last differential). Recovery requires only the full backup plus the most recent differential—simpler than incrementals while still more storage-efficient than daily full backups.

System state backups capture the operating system’s configuration without necessarily copying all user data. On Windows, system state includes the Windows Registry, system files, boot files, Active Directory (on domain controllers), and other OS-critical components. Restoring system state can repair a corrupted OS installation without affecting user files. This targeted backup type is particularly valuable for servers and enterprise environments.

File-level backups operate on individual files and directories, allowing selective backup of specific folders (Documents, Pictures, Desktop) and granular recovery of individual files. File-level backups support versioning—keeping multiple versions of the same file over time—enabling recovery of content that existed at a specific past point. The Windows File History feature and Time Machine on macOS both implement file-level backup with versioning.

Block-level backups operate on storage blocks rather than files, making them more efficient for large volumes with many small changes. Block-level deduplication identifies duplicate blocks across backups, storing unique blocks only once even if the same data appears in multiple files or backup versions. Enterprise backup solutions commonly use block-level approaches for efficiency at scale.

Bare-metal backups (also called disk images) capture the complete bit-for-bit content of an entire storage device or partition, including the operating system, all installed applications, user data, system configuration, partition table, and boot information. Restoring a bare-metal backup completely recreates the original system state on new hardware, enabling recovery from catastrophic failures like drive replacement without OS reinstallation. The Windows System Image Backup and macOS’s Time Machine create formats enabling bare-metal-style recovery.

Continuous data protection (CDP) captures every change to data in real-time rather than at scheduled intervals, theoretically allowing recovery to any point in time with no data loss window. CDP is computationally intensive and storage-demanding, making it primarily an enterprise feature for databases and critical systems. Consumer-facing cloud storage with versioning (Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive) provides a less comprehensive but accessible approximation of CDP.

Windows Backup and Restore Features

Windows provides multiple built-in backup mechanisms addressing different protection needs, with capabilities having evolved significantly across Windows versions.

File History is Windows 10 and 11’s primary user file backup feature. When enabled and configured with an external drive or network location, File History continuously monitors your Libraries, Desktop, Contacts, and Favorites folders, copying changed files to the backup location at configurable intervals (default every hour). File History maintains multiple versions of each file going back as far as the backup location has space. Recovery is accessible directly from File Explorer—right-clicking a file or folder shows “Restore previous versions,” allowing browsing through saved versions and restoring specific previous versions. File History is excellent for recovering from accidental file modification or deletion but doesn’t capture system settings or application configurations.

Windows Backup (Settings > System > Storage > Advanced storage settings > Backup options) in Windows 10/11 provides a simplified interface for configuring File History and accessing backup settings. The newer OneDrive-integrated backup option automatically syncs Desktop, Documents, and Pictures to OneDrive, providing cloud-based backup with versioning—though this requires an OneDrive subscription for adequate storage.

System Restore provides system state recovery without affecting user files. When enabled (it’s on by default for the system drive), Windows automatically creates restore points before significant events: installing applications, installing Windows updates, installing drivers, and major system changes. Users can also create manual restore points. Restore points capture the Windows Registry, system files, certain program files, and system settings—enough to reverse changes that break system stability. Restoring to a previous restore point reverts system files and Registry to that point while leaving user documents, email, and other personal files unchanged. System Restore doesn’t protect against hardware failure or user file deletion—it specifically targets software configuration changes.

Windows System Image Backup (accessible through the legacy Control Panel > Backup and Restore (Windows 7)) creates full system image backups capturing the complete contents of selected drives. These images can be stored on external drives, DVD media, or network locations. System Image Recovery, accessible from Windows Recovery Environment, restores these images to either the original hardware or compatible replacement hardware. Creating a system image periodically provides insurance against catastrophic failures where the entire system needs to be recreated.

Windows Recovery Environment (WinRE) is a recovery platform built into Windows that provides multiple recovery tools accessible before Windows fully loads. You access WinRE by holding Shift while clicking Restart, through the Advanced startup options in Settings, or automatically when Windows detects repeated boot failures. WinRE includes System Image Recovery (restoring from system image backups), System Restore (restoring to a saved restore point), Startup Repair (automatically diagnosing and fixing boot problems), Command Prompt (manual repair operations), and Uninstall Updates (removing recently installed updates that may have caused problems). WinRE is your primary tool when Windows itself won’t boot, making it essential recovery infrastructure.

OneDrive with version history provides cloud-based file backup with recovery capabilities. Files stored in OneDrive maintain version history (30 days for basic accounts, longer for Microsoft 365 subscribers), allowing recovery of previous versions or restoration of deleted files from the Recycle Bin within that period. Microsoft 365 subscribers also have access to Personal Vault for sensitive files and ransomware recovery features that can restore files to states before ransomware encryption.

Previous Versions (shadow copies) complement File History by using Volume Shadow Copy Service (VSS) to create point-in-time snapshots of volumes. VSS snapshots enable restoring previous versions of files even without File History configured, though availability depends on System Restore being enabled and sufficient disk space. Right-clicking a file or folder and selecting Properties > Previous Versions tab accesses these VSS-based snapshots.

macOS Backup and Restore Features

macOS provides Time Machine as its signature backup solution, supplemented by cloud-based features and recovery utilities.

Time Machine is Apple’s comprehensive backup system that has been included with macOS since 2007. Time Machine performs hourly backups for the past 24 hours, daily backups for the past month, and weekly backups for all previous months, automatically deleting oldest backups when the backup drive fills. The Time Machine interface presents a visually distinctive “go back in time” view showing your file system at different past times, allowing browsing through backup history and restoring individual files, folders, or the entire system.

Time Machine backup destinations include directly connected external drives, network-attached storage (NAS) devices supporting Time Machine, and Apple’s Time Capsule (discontinued but still functional). macOS Monterey and later support multiple backup destinations, allowing Time Machine to alternate between a local external drive and a network location for redundancy.

Complete system restoration from Time Machine allows reinstalling macOS and then restoring from a Time Machine backup, recreating the entire system state including applications, settings, and documents. Migration Assistant uses Time Machine backups (among other sources) to set up new Macs with the previous Mac’s content, making Mac transitions smooth.

macOS Recovery is Apple’s built-in recovery environment, accessed by holding Command+R during boot (Intel Macs) or pressing and holding the power button (Apple Silicon Macs). macOS Recovery provides Restore from Time Machine Backup (complete system restoration), Reinstall macOS (fresh installation while preserving user data), Disk Utility (disk repair and management), Safari (limited web access for research), and Terminal (command-line access for advanced repairs). On Apple Silicon Macs, additional recovery options and security configuration are available through a more robust recovery system built into the secure enclave.

iCloud Drive with Desktop and Documents Folders enabled syncs these critical locations to iCloud, providing continuous cloud backup. Files in iCloud Drive maintain 30 days of version history. iCloud Photos continuously backs up the photo library. While not a complete system backup, iCloud provides effective protection for the documents users most frequently need to recover.

Time Machine encryption protects backup privacy by encrypting the backup volume. Encrypted Time Machine backups require the backup password to access, protecting sensitive data on backup drives that might be stolen or lost.

Disk Utility’s First Aid function repairs filesystem errors that can cause data loss or system instability. Running First Aid on volumes with problems often resolves filesystem corruption before it causes data loss, serving as a preventive maintenance function complementing backup restoration.

Linux Backup Tools and Approaches

Linux provides a diverse ecosystem of backup tools with different strengths, giving users flexibility to build comprehensive backup solutions from specialized components.

rsync is the foundational Linux backup tool—a command-line utility for efficiently synchronizing files between locations. rsync only transfers changed portions of files, making incremental synchronization fast even for large directories. “rsync -av –delete ~/Documents/ /backup/Documents/” synchronizes the Documents folder to a backup location, deleting files in the destination that no longer exist in the source. rsync supports network transfers over SSH, enabling remote backups: “rsync -av -e ssh ~/Documents/ user@backupserver:/backup/Documents/”. rsync’s efficiency and flexibility make it a component of many more complex backup solutions.

Timeshift provides Linux users with a System Restore-like experience, creating system snapshots using rsync or BTRFS snapshots depending on the filesystem. Timeshift focuses specifically on system files rather than user data—it’s designed to roll back problematic system updates or configuration changes, not to provide user data backup. When a system update breaks something, Timeshift lets you quickly restore the previous system state while keeping current user data intact.

BorgBackup (Borg) is a modern, feature-rich backup tool emphasizing deduplication and encryption. Borg creates backup repositories where each backup archive contains deduplicated, compressed, and optionally encrypted data—storing unique chunks of data only once across all archives. This deduplication makes Borg extremely storage-efficient: even large repositories with years of backups typically use much less space than naive copying. Borg’s encryption with user-controlled keys ensures backup security even when storing on untrusted servers. Borgmatic simplifies Borg usage with configuration files and automated backup scheduling.

Restic is another modern backup tool with strong deduplication, encryption, and multiple backend support. Restic can back up to local directories, SFTP servers, S3-compatible object storage, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage, and other backends. Its consistent interface regardless of backend makes Restic useful for both local and cloud backups using the same commands and configuration.

Amanda (Advanced Maryland Automatic Network Disk Archiver) is an enterprise-oriented backup system supporting scheduled backups of multiple client machines to a central backup server. Amanda handles backup scheduling, tape rotation (for environments using tape storage), network bandwidth management, and backup verification—suitable for managing backups across many Linux servers.

Bacula is another enterprise backup solution with comprehensive scheduling, client-server architecture, support for various backup media types, and detailed reporting. Bacula is commonly used in enterprise Linux environments requiring centralized backup management.

The systemd timer system (replacing cron for many purposes) can schedule any backup command. Combining systemd timers with rsync, Borg, or Restic creates automated backup systems with logging through journald and integration with system monitoring. Many Linux users build complete backup solutions from these composable components.

BTRFS and ZFS filesystems include snapshot capabilities as native filesystem features. BTRFS snapshots are nearly instantaneous—creating a snapshot doesn’t copy data, just creating a point-in-time view that references existing data while tracking subsequent changes separately. BTRFS snapshots enable space-efficient local versioning. ZFS similarly provides instantaneous snapshots with efficient space usage through copy-on-write semantics. Filesystem-level snapshots complement rather than replace external backup—they protect against accidental deletion or modification but not against storage failure.

Cloud Backup and Sync Services

Cloud-based backup and synchronization services supplement OS-native backup mechanisms with offsite protection accessible from anywhere.

Cloud synchronization services like Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, and iCloud Drive continuously mirror designated folders to cloud storage. Any file saved in synced folders immediately uploads to the cloud and synchronizes to other devices. These services provide version history (typically 30-180 days depending on service tier) allowing recovery of previous versions or restoration of deleted files. Cloud sync effectively provides continuous, automatic, offsite backup for synced folders—addressing the “offsite” requirement of the 3-2-1 rule effortlessly.

Dedicated cloud backup services like Backblaze Personal Backup, Carbonite, or IDrive differ from sync services by operating more like traditional backup software: they back up specified files and drives to cloud storage without creating a synchronized local-cloud mirror. Backblaze Personal Backup, for example, continuously backs up all selected files on a computer for a flat monthly fee, maintaining unlimited version history. These services are designed specifically for backup rather than file sharing, often providing better coverage of system files, application data, and external drives.

Backup implications of cloud storage pricing matter practically. Cloud backup requires ongoing storage costs that can become significant. 1TB of backup storage with Backblaze costs around $99/year. Equivalent local NAS storage might cost $200-300 once but requires no ongoing fees. Cloud backup’s advantages—offsite protection, no hardware to manage, accessible from anywhere—justify the cost for most users with important data.

Data sovereignty and encryption concerns affect cloud backup choices. Cloud providers with access to encryption keys can theoretically access backup contents, comply with legal requests for data, or experience breaches that expose backup data. Services offering end-to-end encryption with user-controlled keys (like Borg with cloud backends, or some specialized services) prevent cloud providers from accessing data content. Understanding the encryption model of your cloud backup provider helps assess privacy risks.

Backup application data and system settings to cloud varies by service. Most cloud sync services back up files but not application settings, browser bookmarks, or OS configuration. macOS’s iCloud includes some system settings synchronization. Windows offers settings sync through Microsoft accounts. More complete cloud synchronization of settings reduces setup time when configuring new computers.

Backup Scheduling and Automation

Effective backup requires regular, automatic execution rather than relying on manual processes that are easily neglected.

Backup frequency should match data change rate and acceptable data loss. Files that change frequently warrant more frequent backups. Personal documents that change daily deserve at least daily backup. Rarely modified archives might be backed up weekly. System state that changes primarily during major updates might be captured only before those updates. Most systems benefit from a tiered approach: real-time cloud sync for active documents, hourly file history for local versioning, nightly full incremental backup to external drive.

Event-triggered backups capture state before risky operations. Windows System Restore automatically creates restore points before significant system changes. Before major software installs, OS updates, or system configuration changes, creating manual backups provides insurance against changes that break things. Scripted backups can run before deployment operations in server environments.

Testing backup integrity regularly verifies that backups are actually usable. Backup files can become corrupted, backup destinations can fail, or backup software can malfunction while appearing to succeed. Periodically attempting to restore files from backup—actually reading and verifying restored files—confirms the backup system works. Many backup tools include verification modes that check backup integrity without requiring full restoration.

Monitoring backup execution ensures backups are completing successfully. Operating system event logs, backup software logs, and email notifications from backup tools all provide visibility into whether scheduled backups are running and succeeding. Administrators monitoring server backups configure alerts for backup failures. Home users benefit from checking backup software logs periodically.

Retention policies manage how long backups are kept. Keeping every backup forever fills storage eventually. Automated retention policies—delete hourly backups older than 24 hours, daily backups older than 30 days, weekly backups older than 6 months, monthly backups older than 2 years—balance storage costs against recovery flexibility. Long retention periods provide protection against discovering data loss that occurred months ago.

Performing Recoveries

Understanding how to actually perform recoveries is as important as setting up backups—backups only help if you can successfully recover from them.

File-level recovery from File History (Windows) or Time Machine (macOS) uses the respective backup application’s browsing interface. File History recovery opens the historic view of the backed-up folder at the point you select, with arrows to navigate through time and a restore button to recover selected files to their original locations or a chosen alternative location. Time Machine provides similar functionality with its distinctive space-themed interface. Both allow recovering individual files, entire folders, or all files at once.

System Restore recovery on Windows walks through a wizard interface accessible from System Properties > System Protection > System Restore, or from Windows Recovery Environment. The wizard shows available restore points with their dates, types, and the programs that will be affected. Previewing affected programs shows what was installed or removed since the selected restore point. Confirming the restore reboots and applies the restore point, typically completing in 15-30 minutes.

Full system image recovery on Windows uses the “System Image Recovery” option in Windows Recovery Environment. This option searches for available system images, presents them for selection, and then completely overwrites the target drive with the image contents. This is a destructive operation—all current content of the target drive is replaced—so it’s appropriate only when recovering from catastrophic failure requiring complete system recreation.

Time Machine complete restore from macOS Recovery reinstalls macOS and then restores from the most recent (or selected) Time Machine backup. The restoration process transfers all files, applications, and settings, recreating the Mac’s state at the backup time. This process takes several hours for large backups but results in a completely restored system.

Partial restore scenarios often arise—recovering specific files from an image backup that was created for complete system recovery. Windows provides the ability to mount system image files as virtual drives, allowing browsing and copying specific files. Third-party tools can extract files from Time Machine backups. This flexibility means image backups serve double duty as both complete system recovery and file-level recovery sources.

Bare-metal restoration to different hardware requires compatible hardware or appropriate driver injection. Windows System Image recovery to different hardware sometimes works if hardware is similar enough, but may fail or produce non-optimal results with significantly different hardware. Specialized tools like Macrium Reflect or Acronis True Image handle hardware differences better through driver injection during restoration. macOS Time Machine restoration naturally handles different Apple hardware through macOS’s built-in hardware support.

Backup Best Practices and Common Mistakes

Following best practices and avoiding common mistakes ensures backup infrastructure actually protects against data loss.

Test restores regularly to verify backups work. Many people discover their backup system was broken only when attempting to recover from actual data loss—an infuriating moment. Quarterly restore tests of sample files from each backup mechanism verify the complete backup-recovery pipeline is functional. Testing to a different location (rather than overwriting originals) allows verification without risk.

Store backups on separate physical media from backed-up data. A backup stored on the same hard drive as the original provides no protection if that drive fails. External drives, network storage, tape, optical media, or cloud all provide the physical separation needed. Many users keep Time Machine drives plugged in permanently, making them vulnerable to the same threats as the primary drive (ransomware, power surges, theft).

Encrypt backups containing sensitive data. An unencrypted backup drive containing financial records, personal photos, or business data is a significant privacy and security liability if lost or stolen. Both Windows Encrypting File System and macOS FileVault can encrypt backup destinations. Borg, Restic, and many other backup tools include built-in encryption. The inconvenience of encrypting backups is vastly outweighed by the risk of unencrypted backup data falling into wrong hands.

Document the backup and recovery process. When recovering from a crisis, having clear documentation of where backups are, how to access them, what software is needed, and step-by-step recovery procedures prevents confusion and delays. This documentation should be stored somewhere accessible even when the system being recovered is unavailable—printed, stored on a separate device, or kept in cloud storage.

Common mistakes include confusing sync with backup—cloud sync services like Dropbox synchronize deletion, meaning deleted files are removed from all synchronized locations and may only be recoverable within a limited window. Relying solely on sync without separate backup leaves users vulnerable to accidental deletion propagating everywhere. Another common mistake is having only one backup with no redundancy—a single external drive backup provides no protection if that drive fails simultaneously with the primary. Regular testing, redundancy, and offsite storage address these vulnerabilities comprehensively.

Conclusion

System backup and restore functions represent essential operating system infrastructure that stands between you and potentially catastrophic, irreversible data loss. The built-in backup features across Windows, macOS, and Linux provide comprehensive protection through multiple complementary mechanisms—from file versioning that preserves previous versions of individual documents, to system restore points that reverse problematic configuration changes, to full disk image backups that enable complete system recreation after catastrophic hardware failure. These mechanisms exist within every modern operating system specifically because data loss events are not rare edge cases but inevitable realities affecting every computer user eventually.

Understanding backup mechanisms—how they work, what they protect, how to configure them, and critically how to actually recover from them when needed—transforms you from someone who hopes nothing goes wrong into someone who knows they can recover when it inevitably does. The 3-2-1 backup principle provides a practical framework: multiple copies, multiple media types, offsite storage. The combination of local file versioning (File History, Time Machine), local full system backup (Windows System Image, Time Machine), and cloud backup (OneDrive, cloud sync, dedicated cloud backup) addresses all the common failure scenarios with appropriate recovery options.

Backup infrastructure requires modest effort to set up and minimal ongoing attention once configured, yet provides profound peace of mind and genuine protection against events that otherwise cause severe disruption or irreversible loss. Whether you’re protecting personal memories, irreplaceable creative work, or business-critical documents, implementing comprehensive backup following your operating system’s native capabilities augmented with additional solutions where needed represents one of the highest-value investments you can make in your computing experience and data security.

Summary Table: Backup and Restore Features Across Operating Systems

| Feature | Windows | macOS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary File Backup | File History (Settings > Update & Security > Backup) | Time Machine (System Preferences/Settings > Time Machine) | rsync, BorgBackup, Timeshift (user choice) |

| System State Backup | System Restore (restore points) | macOS Recovery + Time Machine | Timeshift, filesystem snapshots (BTRFS/ZFS) |

| Full Disk Image | System Image Backup (Control Panel > Backup and Restore) | Time Machine (full restore) | dd, Clonezilla, Borg, Restic |

| Cloud Backup Integration | OneDrive (Desktop, Documents, Pictures) | iCloud Drive (Desktop & Documents) | Restic/Borg to cloud backends |

| Recovery Environment | Windows Recovery Environment (WinRE) | macOS Recovery (Cmd+R or power button hold) | Live USB/CD, GRUB recovery mode |

| File Versioning | File History + Previous Versions (VSS) | Time Machine versions | BTRFS/ZFS snapshots, Borg archives |

| Bare-Metal Recovery | System Image Recovery in WinRE | Restore from Time Machine in macOS Recovery | Clonezilla, dd restore, Borg extract |

| Backup to Network | File History to network drive, Windows Server Backup | Time Machine to NAS (AFP/SMB) | rsync over SSH, NFS/SMB mounts |

| Backup Scheduling | File History intervals (hourly default), Task Scheduler for images | Automatic hourly/daily/weekly/monthly | cron, systemd timers, backup tool schedulers |

| Encryption Support | BitLocker for backup drives, EFS | FileVault, Time Machine encryption option | LUKS, VeraCrypt, Borg built-in encryption |

| Key Management Tool | Backup and Restore (Control Panel), Settings > Backup | Time Machine preferences, Migration Assistant | Various GUI and CLI tools |

| Ransomware Protection | Controlled Folder Access (Windows Defender), OneDrive version history | Time Machine isolation, iCloud version history | Immutable backups (Borg, Restic append-only) |

| Storage Management | Configurable retention in File History settings | Automatic (fills drive, deletes oldest) | Configurable retention policies in backup tools |

Backup Types Comparison:

| Backup Type | Storage Use | Backup Speed | Restore Speed | Best For | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Backup | 100% (all data) | Slow | Fastest (one source) | Baseline, complete recovery | Weekly full + system images |

| Incremental | Minimal (changes only) | Fastest | Slower (needs chain) | Daily backups, frequent snapshots | File History hourly, Time Machine |

| Differential | Medium (all changes since full) | Medium | Fast (full + one diff) | Balance of speed and simplicity | Enterprise backup schedules |

| Disk Image | 100% (entire disk) | Slow | Fast (block copy) | Bare-metal recovery, migration | Windows System Image, Clonezilla |

| File Sync | Varies (current state only) | Fast (changes only) | Fast (files available) | Accessibility, collaboration | OneDrive, Dropbox, Google Drive |

| Snapshot | Minimal (copy-on-write) | Instantaneous | Very fast | Pre-update protection | System Restore, BTRFS snapshots |

| Cloud Backup | Offsite (managed) | Depends on connection | Depends on connection | Offsite protection, disaster recovery | Backblaze, iCloud, OneDrive |