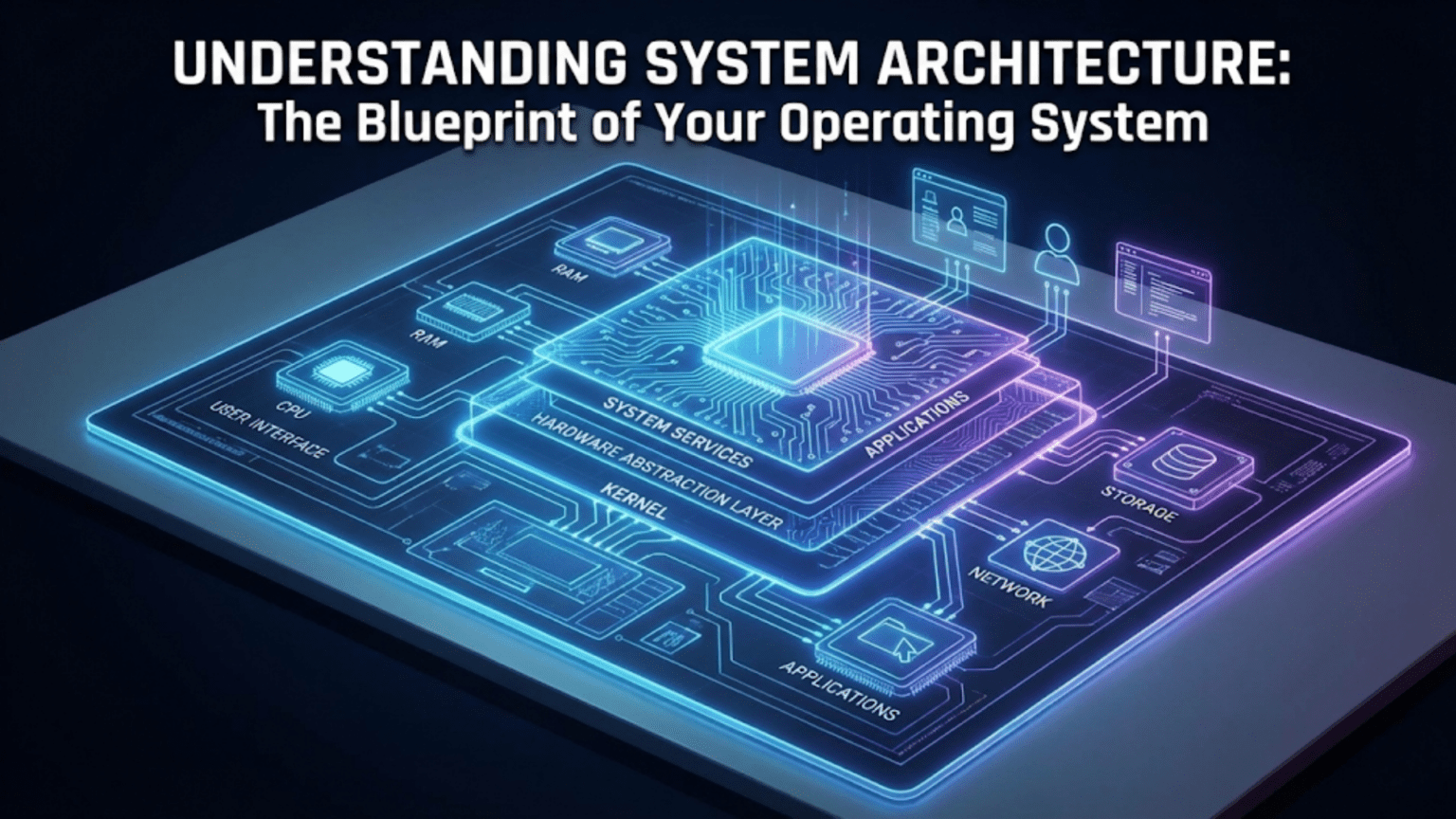

How the Pieces Fit Together to Create a Working System

When you think about your operating system, you might envision the desktop you see, the applications you run, or the files you manage. However, beneath this visible surface lies a carefully engineered architecture that determines how all the components fit together, communicate with each other, and work in concert to provide the computing environment you rely on. System architecture represents the fundamental organizational blueprint that defines which components exist, what responsibilities each component has, and how they interact to accomplish the countless tasks your operating system performs every second. Understanding this architecture reveals why operating systems behave as they do, why certain design decisions create trade-offs between performance and reliability, and how different operating systems choose different architectural approaches to solve similar problems in distinct ways.

The architecture of an operating system profoundly affects its characteristics including performance, security, reliability, and maintainability. An operating system with well-designed architecture cleanly separates concerns so that each component focuses on specific responsibilities without interfering with others, creating natural boundaries that simplify development and testing. Poor architecture creates tangled dependencies where changes in one component ripple unpredictably through the system, making the operating system difficult to maintain and prone to subtle bugs. The architectural choices made by operating system designers in the early stages of development create constraints and possibilities that influence every subsequent decision, much like how the foundation and framework of a building determine what can be built upon them.

Different operating systems adopt dramatically different architectures based on their design goals and the problems their creators considered most important. Some operating systems prioritize maximum performance by allowing components to communicate directly with minimal overhead, accepting the increased complexity and reduced fault isolation that direct communication creates. Others prioritize reliability and security by enforcing strict boundaries between components even though these boundaries introduce performance overhead. Still others attempt to balance these competing goals through hybrid approaches that combine elements from multiple architectural styles. Understanding these architectural variations helps explain why Windows, Linux, and macOS behave differently despite all performing similar fundamental functions, and why certain tasks run faster or more reliably on particular operating systems.

The Kernel: The Core of the Operating System

At the heart of every operating system architecture lies the kernel, which is the privileged software component that has direct access to hardware and manages all system resources. The kernel represents the foundation upon which everything else builds, providing essential services that applications depend on while remaining invisible during normal operation.

The kernel runs in privileged processor mode, often called kernel mode or supervisor mode, where it has unrestricted access to all hardware and memory. This privileged access allows the kernel to control processors, manage memory, coordinate input and output devices, and enforce security policies that protect the system from misbehaving programs. User applications run in unprivileged user mode where they cannot directly access hardware or other programs’ memory, ensuring that bugs or malicious code in applications cannot corrupt the system or interfere with other programs. This separation between privileged kernel and unprivileged user space creates the fundamental security boundary that makes modern multitasking computing possible.

The kernel provides the system calls that applications use to request operating system services. When an application needs to read a file, send network data, create a new process, or perform any operation requiring hardware access or coordination with other programs, it makes a system call that transitions execution from user mode into kernel mode. The kernel validates the request to ensure it is permitted and safe, performs the requested operation using its privileged hardware access, and returns results to the application. This controlled interface ensures applications can accomplish necessary tasks while preventing them from performing unauthorized or dangerous operations.

Core kernel responsibilities include process management where the kernel creates, schedules, and terminates processes, memory management where it allocates and protects memory, device management where it controls hardware through device drivers, and file system management where it organizes persistent storage. These responsibilities are so fundamental that they cannot be delegated to unprivileged components because they require the privileged hardware access and system-wide coordination that only kernel code can provide. Every operating system must implement these core functions, though different architectures organize this functionality differently.

The kernel’s design dramatically affects system characteristics because kernel code runs with unrestricted privileges and cannot be protected from itself the way user applications are protected from each other. A bug in kernel code can crash the entire system, corrupt arbitrary memory, or create security vulnerabilities that compromise all running programs. This makes kernel quality critically important and influences architectural decisions about how much functionality to include in the privileged kernel versus implementing in safer unprivileged user space.

Monolithic Kernel Architecture

The monolithic kernel represents one extreme of operating system architectural approaches where the entire operating system runs as a single large program in kernel mode with all components having direct access to each other and to hardware. This architecture characterized early Unix systems and remains common in modern operating systems including Linux.

In monolithic architectures, device drivers, file systems, network stacks, process schedulers, and all other operating system components execute in kernel mode as parts of a unified kernel. These components can call each other’s functions directly without the overhead of message passing or controlled interfaces, enabling extremely efficient communication between system components. When the file system needs to write data to disk, it calls device driver functions directly. When network code needs to allocate memory, it calls memory management functions directly. This direct communication minimizes overhead and makes monolithic kernels potentially very fast because there is no abstraction barrier between major operating system components.

The advantages of monolithic architecture begin with performance because the lack of boundaries between kernel components eliminates overhead from crossing protection domains. Everything runs in the same privileged address space, so function calls between components are as fast as any function call with no context switching or message copying required. This efficiency made monolithic kernels attractive when computing resources were scarce and every bit of performance mattered. Even on modern systems, the zero-overhead communication between kernel components provides measurable performance benefits for intensive workloads.

However, monolithic kernels have serious disadvantages related to complexity, reliability, and security. The lack of boundaries means any component can corrupt any other component’s data structures, making bugs in one subsystem potentially affect completely unrelated subsystems in unpredictable ways. A bug in a device driver can corrupt file system data structures, leading to data loss. A bug in the network stack can crash the entire kernel and thus the whole system. This tight coupling makes monolithic kernels notoriously difficult to debug because failures in one component often manifest as symptoms in completely different components.

Security vulnerabilities in any kernel component compromise the entire system because all kernel code runs with full privileges. A vulnerability in a device driver provides attackers with the same unlimited access as a vulnerability in the core kernel. This is particularly concerning because device drivers are numerous, developed by many different vendors with varying quality standards, and yet must be trusted completely because they execute in kernel mode. Many security exploits target device drivers specifically because they are a relatively soft target that provides complete system compromise if successfully exploited.

Maintainability suffers in monolithic kernels because the lack of enforced interfaces between components creates tangled dependencies. Changing one component might require updating others that depend on its internal implementation details. The complexity of understanding how modifications might ripple through the system makes adding features or fixing bugs more difficult and risky. Linux, despite being monolithic, has invested tremendous effort in defining internal interfaces and coding standards to manage this complexity, but the fundamental challenge remains that nothing except programmer discipline enforces separation.

Modern monolithic kernels like Linux mitigate some disadvantages through modular design where kernel components are compiled as separate loadable modules that can be added or removed from the running kernel. This modularity provides flexibility to load only needed drivers and allows updating individual components without rebuilding the entire kernel. However, loaded modules still run in kernel mode with full privileges and direct access to kernel internals, so modularity improves organization without providing the fault isolation that true architectural boundaries would create.

Microkernel Architecture

Microkernel architecture represents the opposite extreme where the kernel is minimized to only absolutely essential functionality, with most operating system services implemented as user-mode processes that communicate through message passing. This approach prioritizes fault isolation and security over raw performance.

The microkernel itself contains only the most fundamental mechanisms that must run in privileged mode including basic inter-process communication, minimal process scheduling, low-level memory management, and perhaps interrupt handling. Everything else including device drivers, file systems, and network stacks runs as separate user-mode processes that the microkernel knows nothing about beyond treating them as ordinary processes. These user-mode servers provide operating system services by communicating with applications and each other through message passing mediated by the microkernel.

For example, when an application wants to read a file in a microkernel system, it sends a message to the file system server process. The file system server processes the request, determines what disk blocks need to be read, and sends messages to the disk driver process requesting those blocks. The disk driver communicates with the hardware, retrieves the data, and sends response messages back to the file system server with the data. The file system server then sends a response message back to the application with the requested file contents. Every step involves message passing through the microkernel rather than direct function calls between components.

The advantages of microkernel architecture center on fault isolation and security. Because operating system services run as separate user-mode processes, bugs in one service cannot directly corrupt another service’s memory or crash the entire system. If a device driver crashes, only that driver process terminates while the rest of the system continues running. The microkernel can detect the crash, restart the driver process, and recovery might be possible without requiring system restart. This robustness makes microkernels attractive for systems where reliability is paramount such as embedded systems in vehicles, aircraft, or medical devices where failures could be catastrophic.

Security benefits from the reduced trusted computing base because only the small microkernel runs in privileged mode. Device drivers and other services run with no more privilege than user applications, limiting the damage they can cause if compromised. Security vulnerabilities in a microkernel device driver can only affect that driver’s own operation rather than providing complete system compromise as they would in a monolithic kernel. The strict boundaries enforced by the microkernel prevent components from accessing memory or resources they should not, creating defense in depth.

However, microkernel architecture introduces significant performance costs because every interaction between operating system components requires message passing through the microkernel. Sending a message involves copying data between address spaces, switching execution contexts multiple times, and invoking the microkernel’s message passing code repeatedly. These costs accumulate quickly when simple operations require many messages. Reading a file might involve dozens of messages between the application, file system server, cache manager, and disk driver, with each message introducing overhead. This overhead made early microkernels dramatically slower than monolithic kernels, limiting their adoption despite their theoretical advantages.

Research into optimizing microkernel message passing has reduced this performance gap substantially. Modern microkernels like seL4 use sophisticated techniques to minimize message passing overhead, and some benchmarks show performance approaching monolithic kernels for certain workloads. However, the fundamental tension remains that enforcing isolation and using message passing for communication introduces overhead compared to monolithic kernels’ direct communication.

The complexity of properly structuring a microkernel operating system also presents challenges. Determining which functionality belongs in the microkernel versus user-mode servers requires careful design to avoid excessive message passing while maintaining the fault isolation that is the microkernel’s primary benefit. Getting these boundaries wrong creates systems that combine microkernel overhead with monolithic complexity, providing neither performance nor reliability benefits.

Hybrid Kernel Architecture

Recognizing that both monolithic and microkernel architectures have significant advantages and disadvantages, many modern operating systems adopt hybrid approaches that attempt to combine the best characteristics of each while minimizing their weaknesses. These hybrid kernels make pragmatic engineering trade-offs rather than adhering strictly to architectural purity.

Hybrid kernels keep more functionality in kernel mode than microkernels would but attempt to maintain internal modularity and clean interfaces that monolithic kernels often lack. They might run device drivers in kernel mode for performance but enforce interface boundaries that limit how drivers can interact with the kernel and each other. They might implement key performance-critical services like graphics in kernel mode while relegating less critical services to user mode. The goal is extracting the performance benefits of monolithic architecture where they matter most while achieving microkernel-like isolation and reliability where they provide the greatest value.

Windows NT exemplifies hybrid kernel architecture. The NT kernel runs in privileged mode and includes core scheduling, memory management, and critical device drivers. However, the kernel is structured as separate components that communicate through defined interfaces rather than allowing arbitrary direct access to each other’s internals. User-mode protected subsystems implement much operating system functionality including the Windows API that applications use. This separation provides some fault isolation and architectural flexibility while keeping performance-critical paths in the kernel.

macOS and iOS similarly employ hybrid architecture based on the XNU kernel which combines Mach microkernel message passing with BSD Unix kernel functionality. The Mach portion provides fundamental services like task management and inter-process communication with microkernel principles, while the BSD portion provides file systems, networking, and POSIX compatibility with monolithic architecture. Device drivers run in kernel mode for performance but are isolated through I/O Kit frameworks that limit how they can interact with the kernel. This hybrid approach attempts to combine Unix compatibility and good performance with improved reliability and security over pure monolithic designs.

The advantages of hybrid architecture include performance comparable to monolithic kernels for common operations because critical paths execute entirely in kernel mode without message passing overhead, better fault isolation than pure monolithic designs through enforced interfaces and some user-mode components, and architectural flexibility to make trade-offs on a per-component basis based on specific requirements. This pragmatism allows optimizing for real-world needs rather than adhering dogmatically to architectural ideals.

However, hybrid kernels also inherit disadvantages from both parent architectures. They share monolithic kernels’ vulnerability where bugs in kernel-mode components can crash the system or compromise security, they have more complex architectures than either pure monolithic or microkernel designs, and the mix of architectural styles can create inconsistency where different components follow different patterns. The hybrid approach is fundamentally a compromise that accepts imperfection in pursuit of practical benefits.

Layered Architecture and Abstraction

Beyond the monolithic versus microkernel distinction, operating systems can be organized in layers where each layer uses services provided by lower layers and provides services to higher layers. This layered approach creates organizational clarity and enables abstraction that simplifies each layer’s implementation.

The layered model conceptualizes the operating system as concentric layers with hardware at the center, the kernel providing the first layer of abstraction over hardware, system libraries providing higher-level abstractions over kernel services, and applications as the outermost layer using services from all lower layers. Each layer has well-defined interfaces specifying what services it provides and what services it requires from layers below. This structure creates independence where layers can be modified or replaced without affecting others as long as interfaces remain consistent.

Hardware abstraction layers explicitly separate hardware-dependent code from hardware-independent code, allowing most of the operating system to be written without knowledge of specific hardware details. The HAL provides uniform interfaces for accessing different hardware platforms, presenting standard processor, memory, interrupt, and timer interfaces regardless of whether the underlying hardware is x86, ARM, or another architecture. This abstraction simplifies porting operating systems to new hardware because only the relatively small HAL needs to be rewritten rather than the entire operating system.

Device driver frameworks create another abstraction layer between generic device categories and specific device implementations. A graphics driver framework might define interfaces that all graphics drivers must implement, allowing the operating system to work with any graphics card through the common interface while each driver handles hardware-specific details internally. This framework approach enables supporting new devices without modifying the operating system as long as drivers implementing the required interfaces are available.

The benefits of layered architecture include conceptual clarity where each layer has well-understood responsibilities, portability across different hardware through abstraction layers, and simplified development where programmers can work on individual layers without understanding the complete system. Layering also facilitates modularity where components can be developed, tested, and maintained independently.

The disadvantages involve performance overhead from crossing multiple layers because each layer transition involves function calls, parameter validation, and potentially context switches that accumulate to measurable overhead. Strict layering can also reduce efficiency because optimal implementations sometimes require cooperation between layers that strict layering prohibits. Real operating systems often violate pure layering where performance demands direct communication between non-adjacent layers.

Client-Server Architecture in Operating Systems

Some operating system designs organize functionality using client-server models where client processes request services from server processes, similar to network client-server applications but within a single system. This architectural pattern appears particularly in microkernel systems but influences other designs as well.

In client-server architecture, operating system services like file systems, network stacks, or device drivers run as server processes that client processes communicate with through messages. Clients send requests to servers asking for operations to be performed, servers process these requests using whatever resources they control, and servers send responses back to clients with the results. This pattern creates clean separation between service provision and service consumption.

The advantages include flexibility where servers can be replaced or updated without affecting clients as long as message protocols remain compatible, scalability where multiple server instances can handle requests in parallel, and distribution where servers can run on different processors or even different machines in distributed systems. The explicit request-response pattern also makes debugging and monitoring easier because all interactions happen through well-defined messages rather than hidden function calls.

However, the overhead of message passing and the complexity of managing asynchronous communication between clients and servers create disadvantages. Applications must handle failures where servers crash or stop responding, requiring timeout mechanisms and error handling that direct function calls do not require. The performance costs of message passing limit how fine-grained services can be without excessive overhead.

Modern Trends in Operating System Architecture

Operating system architecture continues evolving as new hardware capabilities and use cases drive innovation in how systems are structured and organized.

Unikernels represent a radical architectural approach where the application and operating system are compiled together into a single purpose-built image that runs directly on hardware or in virtual machines. By including only the operating system components the application actually uses and eliminating the boundary between application and operating system, unikernels achieve minimal size and potentially excellent performance. However, unikernels sacrifice generality for specialization and are suitable only for specific deployment scenarios rather than general-purpose computing.

Exokernels minimize the kernel to just secure resource multiplexing without imposing policy, allowing applications to implement their own specialized operating system abstractions optimized for their specific needs. This architecture challenges the assumption that operating systems should provide high-level abstractions, instead arguing that applications know their requirements better than generic operating systems can and should be free to implement optimal policies.

Container architectures blur traditional operating system boundaries by sharing kernels among multiple isolated user-space environments. Containers provide operating-system-level virtualization where the kernel is shared but each container has its own view of file systems, processes, and network resources. This architecture enables efficient multi-tenancy where many isolated environments coexist on shared infrastructure.

Understanding operating system architecture reveals that there is no single correct way to organize an operating system but rather many viable approaches with different trade-offs. Monolithic kernels maximize performance through direct communication while sacrificing fault isolation. Microkernels prioritize reliability and security through strict boundaries while accepting performance overhead. Hybrid kernels pragmatically combine approaches to balance competing goals. Layered architectures create organizational clarity and abstraction that simplifies development and porting. Each architectural approach reflects different priorities and constraints, and understanding these trade-offs helps appreciate why different operating systems make different design choices in pursuit of similar goals.