A file extension is a suffix at the end of a filename, typically consisting of a period followed by three or four characters (like .txt, .jpg, or .docx), that indicates the file’s format and type. Operating systems use file extensions to determine which application should open a file, what icon to display, and how to process the file’s contents, though different operating systems rely on extensions to varying degrees and handle them in distinct ways.

Every time you double-click a document, view a photo, or play a music file on your computer, your operating system instantly determines which application should open that file. This seamless experience relies heavily on file extensions—those short letter sequences that appear after the dot in filenames. While they might seem like simple labels, file extensions represent a sophisticated system that operating systems use to organize, identify, and manage the thousands of different file types your computer encounters. Understanding how file extensions work and how different operating systems handle them reveals fundamental differences in operating system design philosophy and provides practical knowledge that helps you work more effectively with files across different platforms.

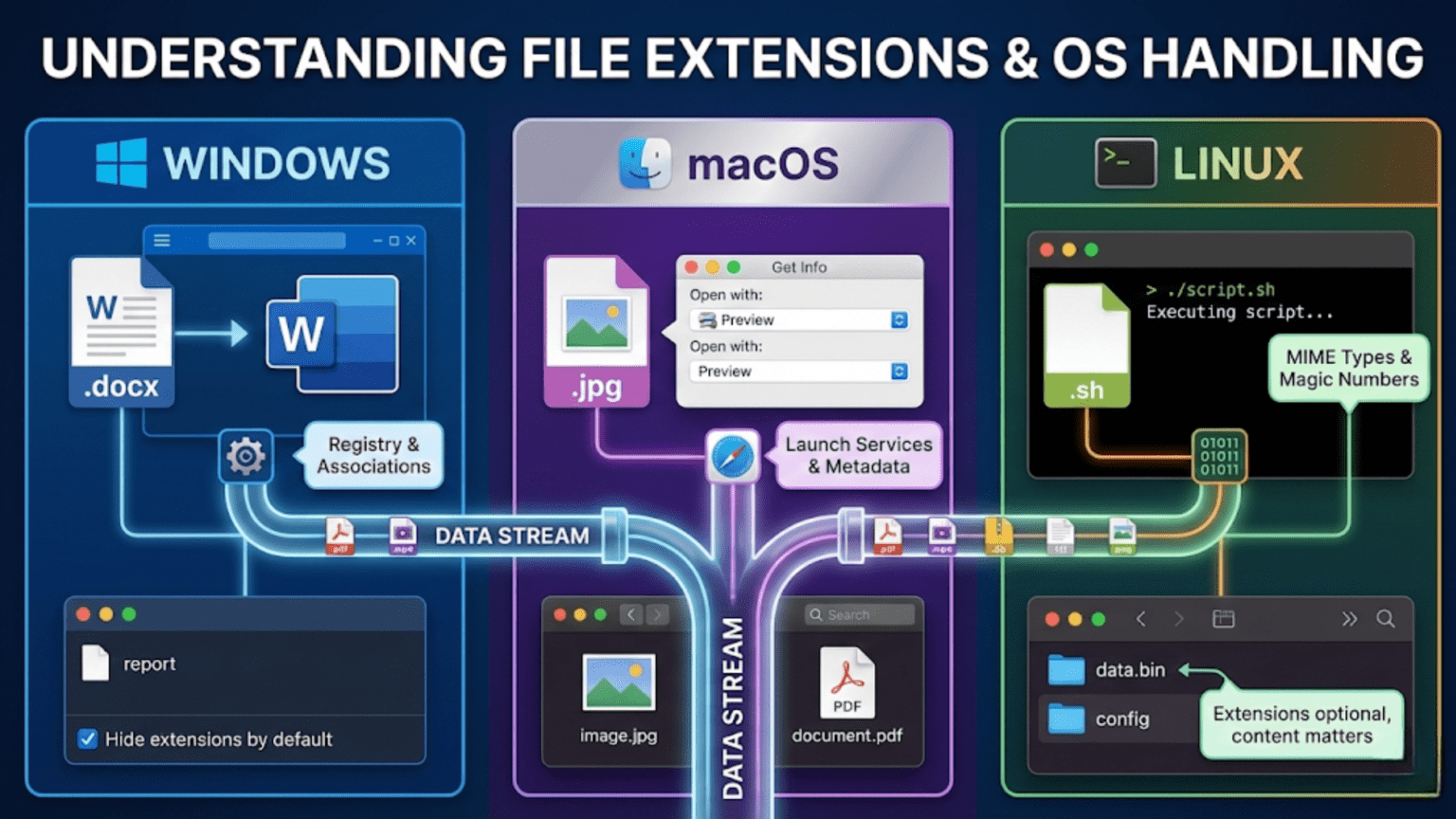

File extensions serve as one of the primary methods operating systems use to classify files, but the extent to which different operating systems depend on these extensions varies dramatically. Windows treats file extensions as critical identifiers that determine file behavior, macOS takes a hybrid approach that considers extensions alongside other file metadata, and Linux generally treats extensions as optional conventions rather than requirements. These different approaches reflect broader philosophies about how computers should interact with users and how much the system should infer from filenames versus file contents. This comprehensive guide explores what file extensions are, how they function at both user and system levels, how different operating systems implement extension handling, and the practical implications these differences have for your daily computing experience.

What File Extensions Are and Why They Exist

A file extension is fundamentally a naming convention—a standardized way to indicate what type of data a file contains by appending specific characters to the end of the filename. The extension typically begins with a period (called a dot) followed by a sequence of characters, usually two to four letters, though extensions can technically be any length. When you see a file named “report.docx,” the “.docx” portion is the file extension, telling you (and your operating system) that this file is a Microsoft Word document in the Office Open XML format.

File extensions originated in early operating systems that had severe filename limitations. The original CP/M operating system, which influenced MS-DOS and subsequently Windows, implemented an “8.3” filename format where filenames could be at most eight characters, followed by a period, followed by a three-character extension. This limitation forced the development of abbreviated extensions like .doc (document), .exe (executable), .txt (text), and .jpg (Joint Photographic Experts Group image format). While modern operating systems no longer enforce these strict length limits and support much longer extensions like .pages or .docx, the convention of short, abbreviated extensions persists as a legacy that most systems still recognize and use.

The fundamental purpose of file extensions is file type identification. When your computer encounters a file, it needs to determine what kind of data the file contains to handle it appropriately. Is this file a text document that should open in a text editor? Is it an executable program that can be run? Is it an image that should be displayed in an image viewer? Is it a video that requires a media player? The file extension provides a quick, simple way to answer these questions without examining the file’s contents.

File extensions create associations between file types and applications. When you install Microsoft Word on your computer, the installation process registers the .docx extension with your operating system, telling the system “I can open .docx files.” Subsequently, when you double-click any .docx file, your operating system checks its registry of file type associations, finds that .docx files should open with Word, and launches Word with that file. This association system allows seamless file opening without you needing to manually specify which application to use for every file.

Extensions also enable security features in operating systems. Certain extensions like .exe, .bat, .sh, or .app indicate executable files that contain program code rather than data. Operating systems treat these files with extra caution, implementing additional security checks before allowing them to run. Email systems and download managers often warn you specifically when you’re about to open executable files, using the file extension as the primary indicator that a file might contain potentially harmful code.

File extensions facilitate file transfer and sharing across different systems. When you send someone a file, the extension helps ensure they can open it on their system. A .pdf file will open in PDF readers on Windows, macOS, Linux, and mobile operating systems. A .mp3 audio file plays on virtually any device with a media player. Standardized extensions create a common language that different systems and applications understand, enabling interoperability in our heterogeneous computing environment.

From a technical perspective, file extensions are simply part of the filename—they’re not stored separately in most file systems. The period separating the extension from the base filename has no special significance to the file system itself; it’s just another character in the filename. The operating system implements the logic to recognize the pattern of “characters.extension” and extracts the extension portion for file type determination. This means you can technically create files with multiple periods (like “my.file.name.txt”) where the OS considers only the final segment after the last period as the extension.

How Windows Handles File Extensions

Windows has the most extension-centric approach among major operating systems, treating file extensions as the primary mechanism for file type identification and making them integral to how the system functions.

At the core of Windows’ extension handling is the Windows Registry, a hierarchical database that stores system and application configuration information. When you install a program that can handle certain file types, the installer adds entries to specific registry locations (primarily HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT) that map file extensions to file type identifiers and associate those identifiers with applications. For example, installing Adobe Acrobat creates registry entries linking the .pdf extension to a file type called “Acrobat.Document.DC” and then associates that file type with the Acrobat executable, complete with command-line parameters for opening files.

Windows implements a detailed file association system that goes beyond simple extension-to-application mappings. Each file type registered in Windows can have multiple associations: the default application for opening files, the application to use for editing, printing actions, context menu entries (right-click menu options), icon specifications, and more. When you right-click a .jpg image and see options like “Open,” “Edit,” “Print,” and “Set as desktop background,” each of these actions is defined in the registry for the JPEG file type. This richness allows extensive customization of how Windows handles different file types.

The File Explorer in Windows makes file extensions both visible and invisible in ways that can confuse users. By default, Windows hides file extensions for “known file types”—files whose extensions are registered in the system. This design decision, intended to simplify the user interface, means most users see “document” rather than “document.docx” in File Explorer. You can change this behavior in Folder Options by unchecking “Hide extensions for known file types,” which is often recommended for security reasons since it prevents malicious files from disguising their true nature (a common trick is naming a virus “photo.jpg.exe” where the real extension is .exe but appears hidden).

Windows treats file extensions as case-insensitive but preserves the case you type. You can name a file “Report.TXT” or “report.txt” or “report.Txt” and Windows considers all of these to have the .txt extension and handles them identically. The file system stores whatever case you use when creating or renaming the file, but when searching or matching extensions, Windows ignores case differences. This case-insensitivity extends to the entire filename in Windows, unlike Unix-like systems where “Report.txt” and “report.txt” would be considered entirely different files.

Windows implements extension-based security policies through several mechanisms. Windows Attachment Manager tracks files downloaded from the internet by adding an alternate data stream to the file containing zone information. When you try to open such a file, Windows checks both the extension and this zone information. Executable extensions from untrusted sources trigger security warnings. Windows Defender and other security software scan files based on extension, applying more rigorous analysis to potentially dangerous file types. Group Policy in corporate environments can block specific extensions entirely, preventing users from opening or saving files with dangerous extensions like .exe, .bat, or .vbs.

The way Windows displays file icons depends heavily on extensions. Each registered file type can specify an icon, either from the associated application’s executable or from a separate icon file. Windows extracts and caches these icons, displaying them in File Explorer to provide visual cues about file types. For unregistered extensions or unknown file types, Windows displays a generic white page icon. Some applications register custom icon handlers that can display previews—for example, image files might show thumbnail previews rather than generic icons, and these preview handlers are registered based on file extension.

Windows also implements extension-based file filtering in many dialogs. When you use File Explorer’s search function and filter by file type, you’re filtering by extension. The “Open” and “Save As” dialogs in applications show dropdown filters based on extensions (like “All Images (*.jpg; *.png; *.gif)”), allowing you to show only relevant file types. These filters are built from the extension associations registered in the system.

Renaming files to change extensions in Windows immediately changes how the system treats the file. If you rename “document.txt” to “document.docx,” Windows will attempt to open it with Word instead of Notepad, even though the file’s actual content hasn’t changed and is still plain text. This can cause errors when applications try to open files they expect to be in certain formats but actually contain different data. Windows does warn you when you try to change a file’s extension, displaying a dialog that says “If you change a file name extension, the file might become unusable,” acknowledging that the extension determines system behavior.

How macOS Handles File Extensions

macOS takes a more nuanced approach to file extensions, using them as important identifiers while also considering other file metadata, creating a hybrid system that balances compatibility with flexibility.

The foundation of macOS file type identification includes extensions but goes beyond them through the use of Uniform Type Identifiers (UTIs). UTIs are hierarchical identifiers that describe file types in a more comprehensive way than simple extensions. For example, a JPEG image has the UTI “public.jpeg” which is a child of “public.image” which is itself a child of “public.data.” This hierarchy allows applications to declare they can handle broad categories of files (like “all images”) without needing to enumerate every image format extension. The system maps file extensions to UTIs, but it can also determine UTIs through other mechanisms.

Historically, classic Mac OS (before OS X) used a system of file type and creator codes stored in the file system metadata. Each file had a four-character type code (like ‘TEXT’ for text files or ‘JPEG’ for JPEG images) and a four-character creator code identifying the application that created it. These codes were stored in the file system separately from the filename, meaning extensions were optional and files could be identified without them. When Apple transitioned to OS X and adopted a Unix-based file system, they gradually phased out type and creator codes in favor of extensions and UTIs, though they maintained backward compatibility for many years.

Modern macOS primarily uses extensions for file type identification but can still read extended attributes that some applications write to files. When you save a file in Pages, for example, the application might write UTI information into the file’s extended attributes (metadata stored separately from the file content but associated with the file in the file system). This metadata helps macOS identify the file type even if the extension is missing or changed. However, for maximum compatibility with other systems, most macOS applications now rely primarily on extensions.

The macOS Finder displays file extensions differently depending on context and user preferences. By default, Finder hides extensions for files with known types, similar to Windows’ default behavior. However, you can show all extensions through Finder Preferences by checking “Show all filename extensions.” Unlike Windows, macOS also allows you to hide or show extensions on a per-file basis—you can right-click any file, select “Get Info,” and check or uncheck “Hide extension” for just that specific file. When an extension is hidden in Finder, it’s still part of the filename; Finder just doesn’t display it visually.

macOS implements Launch Services, a framework that manages the associations between file types (identified by extension, UTI, or other means) and applications. When you double-click a file, Launch Services determines which application should open it by examining the file’s UTI (derived from its extension and any metadata), checking which applications have registered to handle that type, and launching the default application. Applications register their supported file types in their Info.plist files (property list files that describe application capabilities), declaring which extensions and UTIs they can open.

The “Open With” contextual menu in macOS provides flexibility in file associations. When you right-click a file and select “Open With,” macOS displays a list of applications that have registered support for that file type, determined by the file’s extension and UTI. You can choose a different application for one-time use, or select “Always Open With” to change the default application for all files of that type. This change updates Launch Services’ associations, affecting how future files with the same extension will open.

macOS treats file extensions as case-insensitive for matching purposes but case-preserving for display, similar to Windows. The underlying file system (APFS or HFS+ in most cases) can be configured as either case-sensitive or case-insensitive, though the default is case-insensitive. In the more common case-insensitive configuration, “Photo.JPG” and “photo.jpg” refer to the same file, and macOS treats both as JPEG images regardless of case variation in the extension.

Extension modification in macOS triggers warnings but is handled more gracefully than in some systems. When you try to rename a file and change its extension, macOS displays a dialog warning “Are you sure you want to change the extension from ‘.txt’ to ‘.pdf’?” This warning helps prevent accidental changes that could make files unopenable, but the system ultimately allows the change if you confirm. After changing an extension, macOS immediately updates its association, treating the file according to its new extension in Launch Services.

QuickLook, macOS’s file preview feature, relies partly on extensions to determine how to preview files. When you press the spacebar on a selected file, QuickLook loads an appropriate preview generator based on the file type. These generators are registered for specific UTIs (which map to extensions), allowing the system to display PDF previews, image previews, video previews, and even custom previews for proprietary formats if applications provide QuickLook plugins.

macOS also implements security checks based on file extensions, particularly for files downloaded from the internet. Similar to Windows, macOS tags downloaded files with quarantine attributes, and when you try to open such files, the system performs additional verification. Executable types (applications, scripts, disk images) trigger Gatekeeper verification, which checks digital signatures and may warn you about unidentified developers. The quarantine system identifies potentially dangerous file types partly through extensions and partly through content inspection.

How Linux Handles File Extensions

Linux and other Unix-like systems take the most flexible approach to file extensions, treating them primarily as user conventions rather than system requirements, though modern desktop environments have added extension-based features for user convenience.

At the fundamental level, Linux file systems (ext4, XFS, Btrfs, etc.) store filenames as arbitrary byte strings with no special meaning attributed to periods or other characters. The file system doesn’t distinguish between “file.txt” and “filetxt” or recognize any special structure in filenames. The kernel itself doesn’t use extensions to determine file type or behavior—a file is simply a sequence of bytes, and the name is just a label for accessing it.

Linux determines executable status through file permissions rather than extensions. Every file in Linux has permission bits that specify read, write, and execute permissions for the owner, group, and others. A file becomes executable when its execute permission bit is set, which you can do with the chmod +x filename command. This means you can create an executable script or program without any extension at all, or with any extension you want. Many Linux command-line programs have no extensions (like ls, cat, grep), and system binaries in /bin and /usr/bin typically lack extensions entirely.

Despite the system’s extension-agnostic design, Linux uses file extensions as conventions that many programs recognize and respect. Developers typically name C source files with .c extensions, Python scripts with .py, shell scripts with .sh, and so forth, but these are conventions for human convenience and tool integration rather than system requirements. Your text editor might provide syntax highlighting for .py files, recognizing them as Python code, but you could execute a Python script named simply “script” with no extension if it has proper execute permissions and a correct shebang line (#!/usr/bin/env python3).

Modern Linux desktop environments like GNOME, KDE, and XFCE have implemented extension-based file associations for user convenience, making the Linux desktop experience more similar to Windows and macOS. These environments maintain databases (often using the freedesktop.org MIME type system) that map file extensions to MIME types and MIME types to applications. When you double-click a .pdf file in a file manager, the desktop environment checks the MIME database, determines this is a application/pdf type, and launches the default PDF viewer.

The MIME type system in Linux provides more sophisticated file type identification than simple extensions. Applications can register MIME type handlers in .desktop files, declaring which types they support. The system maintains a database in /usr/share/mime/ that includes not just extension mappings but also magic number detection—examining file headers and content to identify types. When you ask a Linux system to determine a file’s type, tools like file or mimetype examine the actual file content rather than just trusting the extension. A file named “photo.txt” containing JPEG data would be correctly identified as a JPEG image, demonstrating Linux’s content-over-name philosophy.

File associations in Linux desktop environments are configured through several mechanisms. System-wide defaults are defined in /usr/share/applications/, while user-specific overrides live in ~/.local/share/applications/. The xdg-mime command allows you to query and modify MIME type associations from the command line. Desktop file managers provide graphical interfaces for changing default applications, similar to macOS’s “Open With” functionality. These associations are based on MIME types, which are determined from extensions and content analysis, creating a more robust system than pure extension matching.

Linux treats filenames as case-sensitive by default in most file systems. “File.TXT”, “file.txt”, and “FILE.TXT” are three completely different files that can coexist in the same directory. This case sensitivity extends to extensions—from Linux’s perspective, .txt and .TXT are different extensions, though MIME type mapping typically handles both through case-insensitive matching. This case sensitivity can cause confusion when moving files from Windows to Linux, where files that appeared to have the same name might suddenly be distinct.

Hidden files in Linux are indicated by a leading dot in the filename, not by a file attribute as in Windows. Any file beginning with a period (like .ba.shrc or .config) is considered hidden and won’t display in normal directory listings (you need ls -a to see them). This convention means that if you name a file .extension with nothing before the first period, Linux considers the entire filename to be the extension portion, and the file is hidden. Some confusion arises with filenames like .tar.gz where the file is hidden but also has a compound extension.

Compound extensions are more common and meaningful in Linux than in other systems. Names like archive.tar.gz are typical, where .tar.gz indicates a gzip-compressed tar archive. While technically only .gz is the extension from a “everything after the last period” perspective, Linux users and tools commonly recognize and refer to multi-part extensions like .tar.gz, .tar.bz2, or .tar.xz as single logical extensions. File managers and MIME type systems often register these compound patterns as distinct types.

Shell scripts and text-based configuration files in Linux often have no extensions or use extensions only for human convenience. A shell script might be named simply backup or backup.sh—both work equally well if the execute permission is set and a proper shebang line exists. Configuration files might be config, config.conf, config.cfg, or any other naming scheme the developer prefers. The system imposes no requirements, leading to more diversity in naming conventions across different applications.

Security in Linux doesn’t rely on extensions to identify dangerous files. Because executable status comes from permissions rather than names, simply downloading a file with an .exe extension doesn’t make it executable or dangerous on Linux. You would need to explicitly grant execute permissions, adding a deliberate step that prevents accidentally running malicious programs. This permission-based security is considered more robust than extension-based identification, though it requires users to understand file permissions.

Common File Extensions and Their Meanings

Understanding the most common file extensions and what they represent helps you work more effectively across different systems and applications.

Document format extensions represent various word processing and text formats. The .txt extension indicates plain text files containing unformatted text with no styling or special formatting—these open in simple text editors on any system. The .docx extension identifies Microsoft Word documents in the Office Open XML format used since Word 2007, containing formatted text, images, styles, and other rich content. The older .doc extension represents Word documents in the earlier binary format. The .pdf extension indicates Portable Document Format files, Adobe’s cross-platform format that preserves exact document appearance regardless of the viewing system. The .rtf extension marks Rich Text Format files, a somewhat universal format that can transfer between different word processors while preserving basic formatting.

Image format extensions cover various ways of storing visual data. The .jpg or .jpeg extension indicates JPEG images, a compressed format ideal for photographs but using lossy compression that discards some image data. The .png extension represents Portable Network Graphics, a lossless format supporting transparency, often used for graphics, logos, and screenshots. The .gif extension identifies Graphics Interchange Format files, supporting simple animations and limited to 256 colors, commonly used for simple web graphics and animated images. The .bmp extension indicates bitmap images in Windows’ native uncompressed format, creating large files. The .svg extension represents Scalable Vector Graphics, XML-based vector images that scale perfectly to any size without quality loss. The .tiff or .tif extension indicates Tagged Image File Format, a flexible format supporting lossless compression and multiple images, popular in professional photography and publishing.

Audio format extensions distinguish various sound encoding methods. The .mp3 extension indicates MPEG Audio Layer III files, a compressed format that revolutionized digital music by significantly reducing file sizes while maintaining reasonable quality. The .wav extension represents Waveform Audio File Format, typically containing uncompressed audio with excellent quality but large file sizes. The .flac extension identifies Free Lossless Audio Codec files, offering compression without quality loss, popular among audio enthusiasts. The .aac extension indicates Advanced Audio Coding, a more efficient compressed format than MP3, often used in Apple products. The .ogg extension represents Ogg Vorbis audio, an open-source alternative to MP3 with comparable quality.

Video format extensions identify various video encoding and container formats. The .mp4 extension indicates MPEG-4 video files, a widely compatible format used for everything from streaming video to smartphone recordings. The .avi extension represents Audio Video Interleave, Microsoft’s older multimedia container format. The .mov extension identifies QuickTime movie files, Apple’s video format that’s now widely supported across platforms. The .mkv extension indicates Matroska video, a flexible open-source container format supporting multiple audio tracks, subtitles, and various codecs. The .wmv extension represents Windows Media Video, Microsoft’s proprietary format. The .webm extension identifies WebM video, an open format designed for web use, supporting modern video codecs.

Archive and compression extensions indicate files containing compressed or bundled content. The .zip extension represents ZIP archives, the most universally supported compression format across all platforms, capable of compressing multiple files into a single archive. The .rar extension indicates RAR archives, which often achieve better compression than ZIP but require specific software to extract. The .7z extension identifies 7-Zip archives, offering excellent compression ratios with an open-source algorithm. The .tar extension represents tape archives, originally used for backups but now common for bundling multiple files without compression on Unix-like systems. The .gz extension indicates gzip compression, often combined with tar as .tar.gz for compressed archives on Linux. The .bz2 extension represents bzip2 compression, another common Linux compression format.

Executable and script extensions identify files containing program code or scripts. The .exe extension indicates Windows executable files, compiled programs that can run directly on Windows systems. The .app extension represents macOS application bundles, directories containing all components of a Mac application. The .sh extension identifies shell scripts, text files containing shell commands for Unix-like systems. The .bat extension indicates Windows batch files, containing commands that Windows executes in sequence. The .py extension represents Python scripts, containing Python programming code. The .js extension identifies JavaScript files, containing code that runs in web browsers or Node.js environments. The .jar extension indicates Java Archive files, containing Java programs and their resources.

Web-related extensions identify files used in web development and delivery. The .html or .htm extension represents HyperText Markup Language files, the fundamental format for web pages. The .css extension indicates Cascading Style Sheet files, controlling the visual appearance of web pages. The .php extension represents PHP script files, containing server-side code that generates dynamic web content. The .asp or .aspx extensions identify Active Server Pages, Microsoft’s server-side scripting technology. The .json extension indicates JavaScript Object Notation files, a lightweight data interchange format widely used in web APIs and configuration.

Spreadsheet extensions identify various tabular data formats. The .xlsx extension represents Microsoft Excel workbooks in the Office Open XML format, containing worksheets with formulas, formatting, and charts. The older .xls extension indicates Excel files in the earlier binary format. The .csv extension represents Comma-Separated Values files, plain text files storing tabular data with commas separating columns, readable by virtually any spreadsheet program or database. The .ods extension indicates OpenDocument Spreadsheet files, an open standard supported by LibreOffice and other applications.

Presentation format extensions identify slideshow files. The .pptx extension represents Microsoft PowerPoint presentations in the Office Open XML format, containing slides with text, images, animations, and transitions. The older .ppt extension indicates PowerPoint files in the earlier binary format. The .odp extension represents OpenDocument Presentation files, an open standard used by LibreOffice Impress and other presentation software.

File Extension Best Practices and Common Issues

Working effectively with file extensions across different systems requires understanding best practices and how to handle common issues that arise.

Always include appropriate file extensions when creating files. Even on systems like Linux where extensions are optional, including them provides valuable information to other users, makes files more portable across systems, and ensures proper handling by desktop environments and applications. A Python script named backup.py communicates its nature more clearly than one simply named backup, especially when sharing with others or working on Windows systems where extensions are critical.

Be cautious about hidden extensions, particularly on Windows. The default Windows setting that hides extensions for known file types creates security vulnerabilities because malicious files can disguise themselves. A file named photo.jpg.exe appears as photo.jpg when extensions are hidden, tricking users into thinking it’s an innocent image when it’s actually an executable program. Enable “Show file extensions” in Windows Explorer options to see full filenames and identify potentially dangerous files.

Understand that changing a file’s extension doesn’t convert the file’s contents. If you rename image.png to image.jpg, you haven’t converted a PNG image to a JPEG—you’ve just changed the label. The file still contains PNG data, and applications expecting JPEG format will fail to open it. Actual file format conversion requires specialized software that reads the source format and writes the destination format. Many users make this mistake, expecting simple renaming to change file types.

When transferring files between different operating systems, preserve extensions even if they’re not required. Files created on Linux without extensions might transfer to Windows where they become unopenable because Windows doesn’t know how to handle them. Similarly, files with unusual or missing extensions on macOS might cause issues on Windows. Following cross-platform naming conventions (lowercase extensions, avoiding special characters, including standard extensions) ensures maximum compatibility.

Be aware of case sensitivity differences. Files named Document.TXT and document.txt are the same file on Windows and macOS but different files on Linux. When moving files from Linux to case-insensitive systems, you might encounter conflicts if two files exist with the same name in different cases. Conversely, software developed on case-insensitive systems might fail on Linux if it assumes case-insensitive filename matching.

Recognize compound extensions and their meanings. Extensions like .tar.gz, .tar.bz2, or .tar.xz indicate files that have been processed through multiple stages (first archived with tar, then compressed with gzip, bzip2, or xz). Understanding compound extensions helps you choose the correct extraction tools and understand file processing history. Some Windows programs might only recognize the final extension (.gz) and not handle the compound extension properly.

Avoid spaces and special characters in filenames and extensions. While modern systems support spaces and many special characters in filenames, some command-line tools and scripts have difficulty processing them, requiring special escaping or quoting. Characters like ?, *, <, >, |, \, /, and : have special meanings in various contexts and can cause problems. Stick to alphanumeric characters, hyphens, and underscores for maximum compatibility across systems and tools.

Understand extension-based content filtering in corporate and security contexts. Many organizations block email attachments or file downloads based on extensions, preventing users from receiving .exe, .bat, .vbs, or other potentially dangerous file types. Security software scans files differently based on extensions, applying more scrutiny to executable types. Attempting to bypass these filters by renaming extensions can trigger security alerts or cause the files to malfunction.

Use double extensions sparingly and with awareness of how systems interpret them. A file named archive.tar.gz is interpreted differently across systems—some recognize the compound extension as indicating a gzipped tar archive, while others see only .gz as the extension. When using double extensions, ensure they follow common conventions that tools recognize, and be prepared for some systems to handle them inconsistently.

When file associations are incorrect (wrong program opens when you double-click a file), use your operating system’s association management features to fix them. On Windows, right-click the file, choose “Open with,” select “Choose another app,” and check “Always use this app to open .extension files.” On macOS, use “Get Info” and the “Open with” section to change associations. On Linux, use your desktop environment’s default applications settings or the xdg-mime command. Incorrect associations often result from installing multiple programs that can handle the same file type, where the last installation changed the default.

Be mindful of executable extensions when writing scripts or programs for cross-platform use. A shell script might work perfectly on Linux as script.sh (or even just script), but Windows users might not know what to do with it. Providing both Unix-style scripts and Windows batch file equivalents (.bat or .cmd), or using cross-platform scripting languages like Python that work similarly on all systems, improves usability for diverse users.

Extension Ambiguity and Conflicts

File extensions sometimes create ambiguity or conflicts where the same extension might represent different file types, or where different systems interpret extensions inconsistently.

The .dat extension exemplifies extreme ambiguity—it generically means “data” but provides no specific information about the actual file format. Hundreds of different applications use .dat for their data files, from email programs to games to system applications. Without additional context, a .dat file is nearly impossible to identify, requiring content inspection or knowledge of which application created it. This illustrates the limitation of extensions as file type identifiers when developers choose overly generic extensions.

Some extensions have legitimately represented multiple formats over time. The .ai extension most commonly indicates Adobe Illustrator files but has also been used for other AI-related files in different contexts. The .pages extension represents Apple Pages documents but could theoretically represent other page-layout formats from different developers. These conflicts are generally manageable because they occur in different application domains, but they demonstrate that extensions aren’t always globally unique identifiers.

Three-letter extensions inherited from DOS limitations sometimes create naming conflicts. The .doc extension traditionally meant Microsoft Word documents but could also represent any generic “document” file. The .tmp extension generally indicates temporary files but is used by many different applications with incompatible formats. These ambiguities arose from the severely limited namespace of three-character extensions and persist as legacy issues.

MIME type mapping can be inconsistent across systems. The same extension might map to different MIME types on different Linux distributions or versions, causing the same file to be handled differently. A .txt file might be identified as text/plain, text/x-plain, or even application/txt depending on system configuration, potentially triggering different applications or handling behaviors.

Multiple extensions for the same format create user confusion. JPEG images can have .jpg, .jpeg, or .jpe extensions—all indicate the same format but appear different to users. MPEG video can be .mpg, .mpeg, or .mpe. HTML files might be .html or .htm. These variations arose from historical limitations and platform differences but persist, causing uncertainty about which extension to use and whether different extensions actually represent different formats.

Regional and language variations introduce additional complexity. Some applications use different extensions in different language versions or regions. Localized versions of software might register different extensions or associate the same extensions with different applications, causing files to behave differently when moved between systems in different regions.

Proprietary format evolution creates backward compatibility issues. When Microsoft changed from .doc to .docx with Office 2007, both extensions represented Word documents but with incompatible formats (binary versus XML-based). Newer applications opening .doc files must include legacy format support, while older applications cannot read .docx files without updates. This pattern repeats across many applications that evolve their file formats while maintaining similar extensions.

Extension spoofing represents a security concern where malicious files use deceptive extensions. A file might be named report.pdf.exe where .exe is the actual extension but users only notice the .pdf part. Unicode characters that look like periods can create fake extensions. Right-to-left override characters can visually reverse extension order, making file.exe appear as file.txt in some contexts. These techniques exploit how operating systems display filenames to deceive users about file types.

Character encoding issues sometimes affect extensions. While extensions typically use ASCII characters, some systems allow Unicode in extensions. An extension that appears as .txt might actually contain visually similar Unicode characters, causing the file to be unrecognized by systems expecting standard ASCII extensions. This creates confusing situations where files appear to have correct extensions but aren’t handled properly.

File Extension Management Tools and Utilities

Various tools help users and administrators manage file extensions and their associations across different operating systems.

Windows provides several built-in tools for extension management. The Settings app includes “Default apps” where you can set default programs by file type, reviewing and changing associations for every registered extension. The older Control Panel still includes “Default Programs” with similar functionality but more detailed options. For advanced users, the registry editor (regedit.exe) provides direct access to extension associations in HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT, allowing manual editing of file type definitions, though this requires expertise and care.

The Windows assoc and ftype command-line utilities allow scripting file associations. The assoc command manages extension-to-file-type associations (e.g., assoc .txt=txtfile), while ftype manages file-type-to-application mappings (e.g., ftype txtfile="C:\Windows\notepad.exe" %1). System administrators use these commands in scripts to configure file associations across multiple computers consistently.

macOS includes duti, a command-line utility for managing file associations. While not built into the system, duti is commonly used by administrators and power users to set default applications for file extensions and UTIs programmatically. The built-in defaults command can also manipulate Launch Services associations, though it requires understanding macOS property list structures.

Linux desktop environments provide both graphical and command-line tools. The xdg-mime command queries and sets MIME type associations, allowing you to check which application handles a file type or change the default handler. Desktop file managers like Nautilus (GNOME) and Dolphin (KDE) provide graphical interfaces for changing default applications through “Properties” or “Open With” dialogs, modifying the underlying MIME database.

The file command on Unix-like systems (including Linux and macOS) identifies file types based on content rather than extension. Running file filename analyzes the file’s contents using a database of “magic numbers” (header signatures) and returns a description of the file type. This content-based identification helps verify that files actually contain the data their extensions claim and identifies files with missing or incorrect extensions.

Registry cleaners and file association repair tools exist for Windows to fix corrupted associations. Tools like FileTypesMan (from NirSoft) provide detailed views of all registered file types and extensions, showing associated applications, icons, and actions. When Windows associations become corrupted (often after installing or uninstalling software), these tools can reset associations to defaults or manually fix broken registrations.

Bulk file renaming utilities help manage extensions across many files. Applications like Bulk Rename Utility (Windows), Renamer (macOS), or pyRenamer (Linux) allow you to add, remove, or change extensions on hundreds or thousands of files simultaneously. This is useful when files lack extensions or have incorrect ones, allowing systematic correction without manual renaming.

File conversion tools go beyond extension management to actually convert between formats. Programs like HandBrake for video, ImageMagick for images, or pandoc for documents read files in one format and write them in another, genuinely changing file content to match new extensions. These tools understand that changing extensions alone doesn’t convert files and perform the necessary format transformations.

Specialized extension editors exist for developers and system administrators. On Windows, tools like Default Programs Editor provide comprehensive interfaces for creating, modifying, and deleting file type associations, context menu entries, and icon assignments. These tools are essential when developing applications that need to register custom file types and extensions.

Web-based file identification services help when you encounter unknown file types. Websites that analyze uploaded files or provide searchable databases of extensions help identify mysterious files. These services examine file headers, compare against known formats, and often suggest appropriate software for opening unknown file types.

The Future of File Extensions

File extension handling continues to evolving as operating systems and applications develop new approaches to file management and type identification.

Content-based identification is becoming more prevalent alongside traditional extension-based systems. Modern operating systems increasingly examine file contents to verify they match claimed extensions and to identify files with missing or incorrect extensions. Machine learning models can analyze file structures to identify formats even when extensions are misleading, providing more robust file type determination that doesn’t solely rely on naming conventions.

Cloud storage and synchronization services are changing how we think about file types. Services like Google Drive can open many document types in web applications regardless of extension, converting them on the fly. When you upload a .docx file to Google Drive, you can open it in Google Docs without needing Microsoft Word. This application-agnostic approach reduces the importance of extensions for determining which application should open a file, shifting toward capability-based systems where the service determines the best way to render content.

Mobile operating systems like iOS and Android largely hide file extensions from users, presenting files primarily through application-centric views. Rather than browsing folders of files with visible extensions, mobile users typically work within applications that access their associated file types. This represents a shift away from file-centric interfaces toward document and application-centric models where extensions become implementation details rather than user-facing concepts.

WebAssembly and progressive web applications are creating scenarios where traditional files and extensions matter less. Applications increasingly run in web browsers, working with cloud-stored data that may never exist as discrete files with extensions on the user’s device. The traditional model of downloading files with extensions, storing them locally, and opening them with appropriate applications is gradually complemented (though not replaced) by streaming, cloud-based workflows.

Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) and Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) serve similar purposes to extensions in web contexts, using schemes like http://, mailto:, tel:, or custom schemes to indicate content type and handling method. As computing becomes more network-centric, these URI schemes increasingly compete with traditional file extensions as type identifiers, with operating systems associating URI schemes with applications much like they associate extensions.

Extended attributes and alternate data streams provide richer metadata storage than simple extensions. Modern file systems can store arbitrary metadata attached to files, allowing more sophisticated type identification and file description than extensions alone provide. As these capabilities become more widely supported across operating systems and applications, they may supplement or partially replace extension-based type identification, though extensions will likely persist for backward compatibility and cross-platform portability.

Containerized file formats blur the line between single files and directories. Formats like .docx, .odt, .epub, and others are actually ZIP archives containing multiple files in structured directories. These containers include manifest files that definitively describe content type, reducing reliance on the outer extension. As this approach spreads, the extension increasingly serves as a hint to the zip format plus a convention for the internal structure rather than a precise format identifier.

Blockchain and decentralized systems are exploring content addressing where files are identified by cryptographic hashes of their contents rather than names or extensions. In systems like IPFS (InterPlanetary File System), a file’s identifier is derived from its content, making naming arbitrary. While still experimental for general use, this approach could eventually reduce dependence on extension-based identification in some contexts.

The fundamental tension between simplicity and precision will continue shaping extension evolution. Extensions provide simple, visible type identification that works across systems and requires no special tools to view. More sophisticated approaches (content analysis, embedded metadata, MIME types) provide greater accuracy but add complexity. Operating systems will likely continue supporting extensions while layering additional identification mechanisms on top, maintaining backward compatibility while enabling enhanced capabilities.

Conclusion

File extensions represent a simple yet surprisingly complex aspect of operating system design, revealing fundamental differences in how Windows, macOS, and Linux approach file management and user interaction. Windows treats extensions as critical identifiers that determine file behavior through rigid registry associations, making them essential to system operation but creating potential security concerns when hidden from users. macOS adopts a hybrid approach, using extensions as important indicators while also considering other file metadata through UTIs and historical type codes, balancing flexibility with compatibility. Linux treats extensions as helpful conventions rather than requirements, relying on content inspection and file permissions for file type determination, though modern desktop environments have added extension-based features for user convenience.

Understanding these different approaches empowers you to work more effectively across platforms, avoid common pitfalls like extension-based security vulnerabilities, and make informed decisions about file naming and organization. Extensions serve as a universal language that enables file portability and application interoperability, despite their limitations and occasional ambiguities. As computing evolves toward cloud-based, mobile, and web-centric models, extensions persist as valuable metadata that communicates file type quickly and clearly, even as operating systems develop more sophisticated supplementary identification methods. Whether you’re a casual user organizing photos, a developer creating cross-platform software, or an IT administrator managing file associations across an organization, appreciating how different operating systems handle extensions deepens your understanding of fundamental computing concepts and improves your practical computing skills.

Summary Table: File Extension Handling Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | macOS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Critical for file type identification and application launching | Important identifier combined with UTI metadata | Convention for users and tools, not system requirement |

| Storage Location | Part of filename; associations in Windows Registry | Part of filename; associations in Launch Services database | Part of filename; associations in MIME database |

| Default Visibility | Hidden for known types (configurable) | Hidden for known types (configurable per-file) | Typically visible in file managers |

| Case Sensitivity | Case-insensitive matching, case-preserving storage | Case-insensitive by default (file system dependent) | Case-sensitive (file system dependent) |

| Execution Determination | Primarily by extension (.exe, .bat, .com, etc.) | By extension, bundle structure, and permissions | By permission bits, not extension |

| Type Identification | Extension-based with registry lookup | Extension and UTI, with fallback to metadata | Content-based (magic numbers) with extension hints |

| Association Management | Default Programs, Settings, Registry | Launch Services, Get Info, duti utility | MIME database, xdg-mime, desktop settings |

| Security Approach | Extension-based warnings and blocks | Extension-based with quarantine attributes | Permission-based, extension-independent |

| File Without Extension | Shows generic icon, may not open | Can identify via metadata, may not open easily | Works normally if content identifiable or executable |

| Compound Extensions | Generally only recognizes last extension | Recognizes some compound extensions | Commonly recognizes compounds like .tar.gz |

| Icon Display | Based on registered extension associations | Based on UTI associations and metadata | Based on MIME type associations |

| Multiple Extensions Same Format | Each must be registered separately | UTI hierarchy can group related extensions | MIME aliases can consolidate extensions |

| Extension Modification Warning | Yes, warns extension change may break file | Yes, confirms extension change intention | Typically no warning (just a rename) |

| Cross-Platform Compatibility | Requires extensions for proper function | Good with extensions, can handle some without | Best practices include extensions for portability |