When you look at your computer screen right now, you’re witnessing the result of one of the most sophisticated collaborations between hardware and software that occurs in modern computing. Every pixel you see, every color that appears, every smooth animation that plays, and every window that moves across your display represents millions of calculations and coordinated actions happening behind the scenes. Your operating system orchestrates this entire visual symphony, managing the complex process of translating digital information into the images you see on your screen.

Display management is far more intricate than most people realize. It’s not simply a matter of sending some data to your monitor and hoping it appears correctly. Instead, your operating system must coordinate between multiple software layers, communicate with specialized hardware, manage memory buffers, synchronize timing precisely, and handle countless edge cases and special situations. The system must do all of this while maintaining smooth performance, supporting different types of displays, and allowing multiple applications to share screen space simultaneously.

Think about what happens when you simply move your mouse cursor across the screen. That small action requires your operating system to receive input from your mouse, calculate the new cursor position, determine which parts of the screen need to be redrawn, communicate with the graphics hardware about what needs to change, update the frame buffer with new pixel data, and signal the display to refresh with the updated information. All of this happens so quickly and smoothly that you perceive it as instantaneous movement. This represents just the tiniest fraction of what display management actually involves.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll journey through every aspect of how operating systems manage displays. We’ll start with the fundamental concepts of what a display actually is from the computer’s perspective, then dive deep into the layers of software and hardware that work together to create the visual experience you rely on every day. We’ll examine frame buffers, graphics drivers, display protocols, multi-monitor management, and much more. By the time we’re finished, you’ll have a thorough understanding of one of the most visible yet least understood aspects of operating system functionality.

The Fundamental Challenge of Display Management

Before we can appreciate how operating systems manage displays, we need to understand the fundamental challenge they face. A computer display, whether it’s a monitor, laptop screen, or even a smartphone display, is essentially a grid of tiny colored lights called pixels. Each pixel can produce different colors by combining varying intensities of red, green, and blue light. Your display might contain millions of these pixels arranged in rows and columns.

The computer’s job is to tell each of these millions of pixels exactly what color to display, and it needs to do this many times per second to create the illusion of smooth motion and responsive interaction. A typical modern display refreshes sixty times per second, meaning the computer must provide completely updated information for every single pixel sixty times every second. Some high-end displays refresh at even higher rates, such as one hundred twenty or one hundred forty-four times per second.

Let’s put this in perspective with some actual numbers. A common display resolution is 1920 by 1080 pixels, often called “Full HD” or “1080p.” This means the display has 1920 pixels across and 1080 pixels down, for a total of 2,073,600 pixels. Each pixel needs information about its color, which is typically stored as three values representing red, green, and blue intensity. If we use one byte for each color component, that’s three bytes per pixel, meaning we need about 6.2 megabytes of data to describe a single complete screen image.

Now multiply that by sixty refreshes per second, and we’re talking about nearly 373 megabytes of data flowing to the display every second, just for a basic Full HD screen. Higher resolution displays like 4K monitors have four times as many pixels, quadrupling these requirements. And this is just the raw data for the display itself, not counting all the processing that happens before the data reaches the display.

The operating system must coordinate this massive data flow while also allowing multiple programs to contribute to what appears on screen, handling window layering and transparency, managing multiple displays if they’re connected, and doing all of this efficiently enough that your computer remains responsive for other tasks. This is the fundamental challenge of display management.

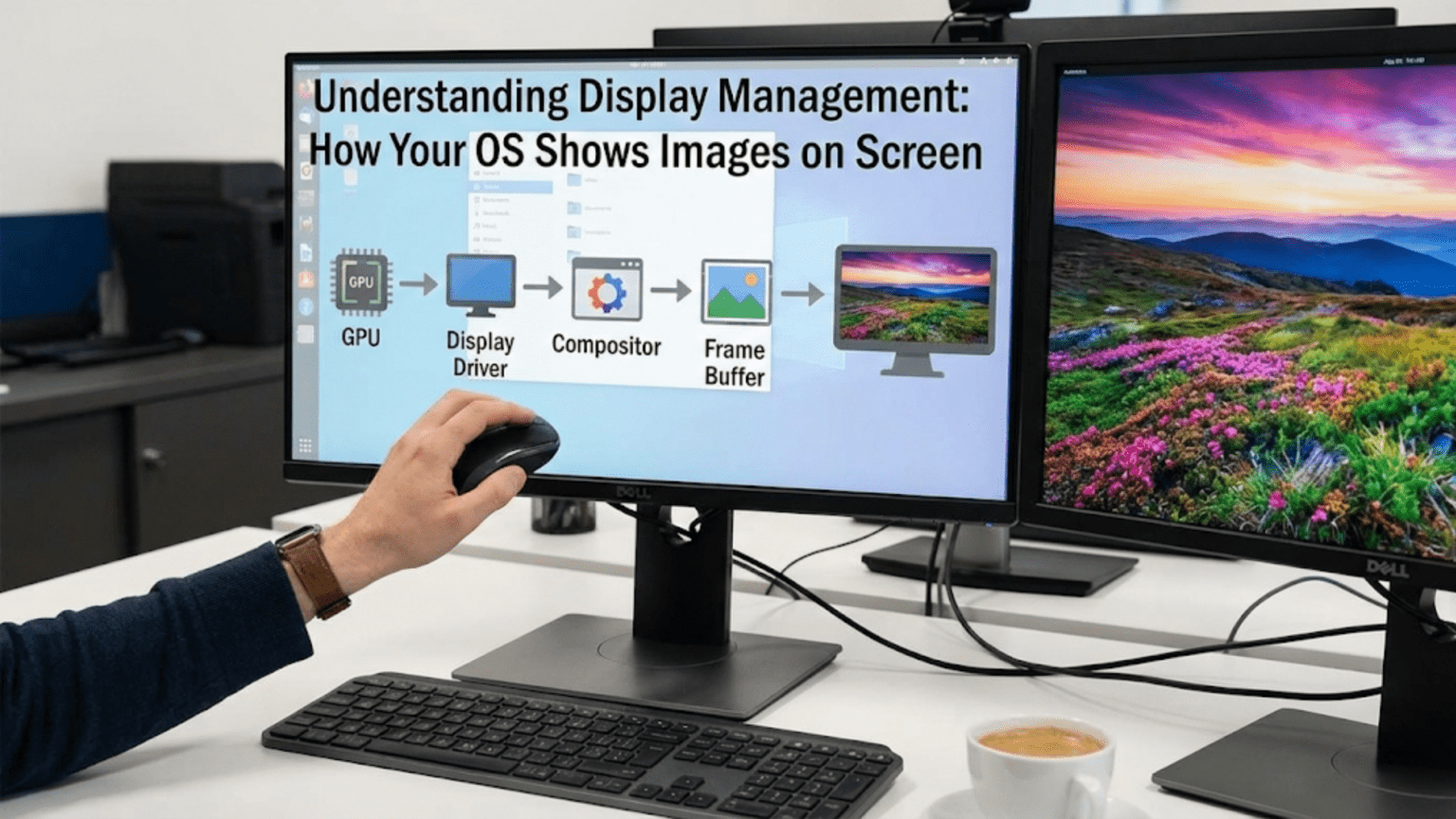

The Display Stack: Layers from Application to Screen

To manage this complexity, operating systems use a layered approach that we often call the “display stack” or “graphics stack.” This stack consists of multiple layers of software, each with specific responsibilities, working together to transform what applications want to show into what actually appears on your screen.

At the very top of this stack sit the applications themselves. When you use a word processor, web browser, or game, that application contains code that describes what it wants to show. However, the application doesn’t directly control the display hardware. Instead, it uses higher-level abstractions provided by the operating system. The application might say something like “draw a blue rectangle here” or “render this text with this font at this location,” but it expresses these desires in relatively abstract terms.

These application requests then pass through several intermediate layers. First, they typically go through a graphics API (Application Programming Interface) such as DirectX on Windows, Metal on macOS, or Vulkan on various platforms. These APIs provide standardized ways for applications to describe what they want to draw, without needing to know the specifics of the actual hardware that will do the drawing.

The graphics API then translates these requests into lower-level commands that can be understood by graphics drivers. The graphics driver is a specialized piece of software provided by the manufacturer of your graphics hardware (companies like NVIDIA, AMD, or Intel). This driver knows the intimate details of how your specific graphics card works and translates the standardized API commands into hardware-specific instructions.

The graphics driver communicates with the actual graphics processing unit, or GPU, which is specialized hardware designed specifically for the task of rendering graphics. The GPU performs the actual computational work of figuring out what color each pixel should be, storing this information in a special area of memory called the frame buffer.

Finally, the display controller, which might be part of the GPU or separate hardware, reads from the frame buffer and sends the appropriate signals to the physical display, which lights up its pixels accordingly. This entire process, from application request to lit pixels, happens continuously and rapidly, creating the dynamic, responsive visual experience you see.

Understanding this layered approach is crucial because it helps explain why display management is distributed across so many different components, and why problems with display can originate from various different sources. It also helps explain why operating system display management is both powerful and complex.

Frame Buffers: The Canvas for Your Screen

At the heart of display management is a concept called the frame buffer. Understanding frame buffers is essential to understanding how display management works, because the frame buffer is where the actual image that appears on your screen exists in memory at any given moment.

Imagine a frame buffer as a large array in computer memory, where each element in the array represents one pixel on your display. For a Full HD display with 1920 by 1080 pixels, the frame buffer contains 2,073,600 entries, one for each pixel. Each entry stores information about that pixel’s color, typically as separate values for red, green, and blue intensity.

In the simplest implementation, which was common in early computer systems, there would be exactly one frame buffer, and whatever was stored in that buffer was exactly what appeared on the display. When a program wanted to change what appeared on screen, it would directly modify the contents of the frame buffer, and those changes would immediately be visible on the display.

However, modern systems are far more sophisticated. Contemporary operating systems typically use multiple buffers to create smoother, more complex visual effects. One common technique is called “double buffering.” With double buffering, the system maintains two complete frame buffers. While one buffer (the “front buffer”) is being displayed on screen, applications and the operating system work on drawing the next frame into the second buffer (the “back buffer”). Once the back buffer is completely ready, the system performs a very quick swap, making the back buffer the new front buffer and vice versa.

This technique solves a problem that plagued earlier systems: tearing. Tearing occurs when the display updates while the frame buffer is only partially updated with new content, causing you to see part of the old frame and part of the new frame simultaneously, creating a visible horizontal line where they meet. By using double buffering and only swapping buffers during the display’s vertical blanking interval (the brief moment when the display has finished drawing one frame and before it starts drawing the next), the system ensures you always see complete, coherent frames.

Some systems even use triple buffering, maintaining three complete frame buffers. This can provide even smoother performance in certain scenarios, particularly when rendering complex 3D graphics, by allowing the GPU to start working on the next frame even while waiting for the appropriate moment to swap buffers.

The operating system must carefully manage these frame buffers, ensuring they’re allocated in the appropriate type of memory (usually video memory on the graphics card for performance reasons), tracking which buffer is currently being displayed, coordinating buffer swaps, and managing access so multiple applications can contribute to what appears on screen without interfering with each other.

The Display Controller and Communication with Monitors

While the frame buffer holds the image data, something must actually send that data to the physical display. This is the job of the display controller, a hardware component that reads from the frame buffer and generates the signals that the monitor needs to light up its pixels appropriately.

The display controller operates on a strict timing schedule. Modern digital displays expect to receive image data in a very specific format and timing. The controller reads through the frame buffer in a predetermined order, typically from left to right, top to bottom, converting the stored pixel data into the electrical signals the display expects.

For digital displays using standards like HDMI, DisplayPort, or DVI, this involves encoding the pixel data along with timing signals, audio data (in the case of HDMI and DisplayPort), and other information into a high-speed digital stream. The display controller must generate this stream precisely according to the specifications of the chosen display standard, including exact timing for horizontal and vertical synchronization signals that tell the display when each row of pixels ends and when the entire frame is complete.

The operating system works with the display controller through the graphics driver, configuring it with information about the display’s capabilities. When you connect a monitor to your computer, the system goes through a process called EDID (Extended Display Identification Data) exchange. Your monitor contains a small memory chip that stores information about its capabilities: what resolutions it supports, what refresh rates it can handle, what color spaces it understands, and other technical specifications.

The operating system reads this EDID data and uses it to configure the display controller appropriately. If your monitor reports it can handle 1920 by 1080 at 60Hz, the operating system configures the display controller to output exactly that. If you have a fancy high-resolution monitor that can do 3840 by 2160 at 120Hz, the system can configure itself to take advantage of those capabilities.

This negotiation process is more complex than it might seem. The system must ensure that the graphics hardware can actually generate the required signal, that there’s enough memory bandwidth to support the data rate, and that the cable connecting the computer to the display has sufficient capacity for the chosen settings. This is why you sometimes can’t select certain resolution and refresh rate combinations, even though your monitor might technically support them in isolation.

The operating system also manages adaptive sync technologies like NVIDIA G-Sync or AMD FreeSync, which allow the display’s refresh rate to vary dynamically to match the rate at which the graphics card is generating frames. This requires careful coordination between the operating system, graphics driver, and display hardware to adjust timing on the fly while maintaining a smooth, tear-free visual experience.

Graphics Drivers: The Critical Translators

Graphics drivers deserve special attention because they play such a crucial role in display management, sitting at the intersection between the operating system’s high-level abstractions and the hardware’s low-level reality. Understanding what graphics drivers do and why they’re so important helps explain many aspects of display management.

A graphics driver is specialized software provided by the manufacturer of your graphics hardware. If you have an NVIDIA graphics card, you use NVIDIA drivers. If you have AMD graphics, you use AMD drivers. Intel integrated graphics use Intel drivers. These drivers are distinct from the operating system itself, though they integrate deeply with it.

The primary job of the graphics driver is translation. When applications or the operating system want to perform graphics operations, they do so through standardized APIs like DirectX, OpenGL, Vulkan, or platform-specific APIs like Metal on macOS. These APIs provide a consistent interface that applications can use regardless of what specific graphics hardware is installed in the computer.

The graphics driver takes these standardized API calls and translates them into the specific commands that your particular graphics card understands. Different graphics cards, even from the same manufacturer, can have significantly different internal architectures. A high-end graphics card might have thousands of processing cores and complex memory hierarchies, while an integrated graphics chip might have far fewer resources and different capabilities. The driver abstracts away these differences, presenting a consistent interface to software while optimizing for the specific hardware’s strengths and working around its limitations.

This translation involves sophisticated optimization. Graphics drivers contain compilers that translate shader programs (small programs that run on the GPU to calculate lighting, textures, and effects) into the machine code for your specific GPU. They manage memory on the graphics card, deciding what textures, buffers, and other data to keep in fast video memory versus system memory. They schedule work across the GPU’s many processing units, attempting to keep the hardware as busy as possible.

Graphics drivers also handle many aspects of display management directly. They configure display timings, manage multiple monitors, implement features like hardware cursor overlay, and handle video decode acceleration. When you adjust your monitor’s resolution or refresh rate in your operating system’s settings, you’re actually configuring parameters that the graphics driver will use to program the display controller.

The complexity of graphics drivers is reflected in their size and development effort. A modern graphics driver can contain millions of lines of code and is continuously updated by teams of engineers. Graphics driver updates often include optimizations for specific new games, bug fixes for rendering issues, and support for new features. This is why graphics drivers are updated so frequently and why these updates can sometimes have significant performance impacts.

The operating system must provide the infrastructure for graphics drivers to work effectively. This includes kernel interfaces that allow drivers to access hardware safely, memory management support for allocating large buffers, interrupt handling for responding to graphics hardware events, and power management integration to allow the graphics hardware to save energy when possible.

The Window Manager: Composing Multiple Visual Sources

One of the most visible aspects of display management from the user’s perspective is how the operating system handles multiple windows from different applications sharing the same screen. This is the domain of the window manager, a crucial component of modern operating systems that has evolved tremendously over the years.

In early personal computer operating systems, window management was relatively simple. Each application would draw directly into the frame buffer, and the operating system would clip the drawing operations to the rectangular region assigned to that application’s window. If one window overlapped another, the system would ensure that drawing operations from the lower window didn’t overwrite pixels belonging to the upper window.

This approach, while straightforward, had significant limitations. Because applications drew directly to the visible frame buffer, you could often see windows redrawing themselves, particularly on slower hardware. Moving a window could reveal incomplete or corrupted content underneath. Transparency effects were difficult or impossible to implement. And if an application stopped responding while in the middle of drawing, it could leave parts of the screen in an inconsistent state.

Modern operating systems use an approach called compositing, which elegantly solves these problems. With a compositing window manager, each application draws its window content into its own private off-screen buffer, completely isolated from other applications and from what’s currently visible on screen. The application never directly touches the frame buffer that’s being displayed.

The window manager maintains these separate buffers for all visible windows. Then, to create the final image that appears on screen, it combines or “composites” all these individual window buffers into a single final image in the correct order. If Window A should appear in front of Window B, the window manager layers A’s buffer on top of B’s buffer when creating the final composite.

This compositing approach enables sophisticated visual effects that users have come to expect. Transparency and translucency work naturally: when compositing a semi-transparent window, the window manager blends its pixels with what’s behind it. Drop shadows, smooth window animations, and effects like live preview thumbnails become straightforward to implement because the window manager has complete control over the final composition process.

Compositing also improves reliability and smoothness. Since each application draws to its own buffer independently, a misbehaving application can’t corrupt other windows. The window manager can continue to display a window’s last valid content even if the application itself has stopped responding. And because the composition happens in a controlled manner, the system can synchronize it with display refresh to ensure smooth, tear-free presentation.

The window manager must handle many other responsibilities beyond composition. It manages window focus, determining which window receives keyboard input. It handles window decorations like title bars, borders, and close buttons. It implements window snapping, maximizing, and other layout behaviors. It manages multiple virtual desktops or workspaces if the operating system supports them. And it must do all of this efficiently, because users expect window operations to feel instantaneous.

Modern compositing window managers leverage the GPU extensively. Rather than performing composition in software on the CPU, they use the GPU’s powerful parallel processing capabilities to blend window contents together. This is much faster and allows for more complex effects without impacting system responsiveness. The window manager essentially acts as a specialized graphics application, using the same graphics APIs and drivers that games and other graphics-intensive applications use.

Color Management and Accuracy

An often-overlooked aspect of display management is color management: ensuring that colors are represented accurately and consistently across different devices. This might seem simple at first glance, but color management is actually quite complex and involves sophisticated coordination between the operating system, applications, and display hardware.

The fundamental challenge is that different devices represent and reproduce colors differently. Your digital camera captures colors in one way, your computer monitor displays them in another way, and if you print something, the printer reproduces colors in yet another way. Even two monitors from the same manufacturer can display the same digital color value differently due to variations in manufacturing and display technology.

To handle this complexity, operating systems implement color management systems based on color profiles. A color profile is essentially a description of how a particular device interprets or produces colors. Your monitor has a color profile that describes its color characteristics: what shade of red it produces for a particular red value, what its white point is, what its gamma curve looks like, and so on.

When an application wants to display an image, that image also has a color profile (or should have one) describing what colors its color values are meant to represent. The operating system’s color management system compares these two profiles and performs a translation. It adjusts the color values in the image so that when displayed on your specific monitor with its specific characteristics, the colors you see match what the image creator intended as closely as possible.

This process involves sophisticated mathematics, typically working in device-independent color spaces like CIELAB or CIEXYZ that are based on human color perception rather than specific device characteristics. The color management system converts colors from the image’s color space to this device-independent space, then from the device-independent space to your monitor’s color space.

The operating system must integrate color management throughout the display pipeline. When compositing windows, it needs to account for the fact that different applications might be using different color spaces. When displaying video content, it must handle color space conversions appropriately. When interfacing with professional applications like photo editors that demand precise color control, it must provide APIs that allow these applications to manage color explicitly.

Modern operating systems also support wide color gamut displays, which can reproduce a broader range of colors than traditional displays. Managing these displays requires even more sophisticated color handling. The operating system must determine whether content is meant for a standard color gamut or a wide color gamut, and tone map or adjust colors appropriately. It must handle the fact that some applications might produce wide gamut content while others don’t, and ensure everything displays correctly and consistently.

Display calibration is another aspect of color management. Professional users often calibrate their displays using specialized hardware that measures the actual colors the display produces and creates a custom color profile. The operating system must support loading and using these custom profiles, and it must provide tools for users to manage which profile is active for each display.

All of this color management typically happens transparently to the user and even to most applications. The operating system handles it behind the scenes, ensuring that colors are as accurate and consistent as possible given the limitations of the various devices involved. However, the system also provides controls for users who need more precise color management, allowing them to choose color profiles, adjust color behavior, and even temporarily disable color management when needed.

Multi-Monitor Management: Coordinating Multiple Displays

As multiple monitor setups have become increasingly common, operating systems have had to develop sophisticated capabilities for managing multiple displays simultaneously. Multi-monitor management involves numerous challenges beyond simply duplicating or extending the display across multiple screens.

When you connect multiple monitors to your computer, the operating system must first detect them and gather information about each one’s capabilities. Through the EDID exchange process we discussed earlier, it learns what resolutions each monitor supports, their refresh rates, their physical sizes, and other characteristics. The system must configure the graphics hardware to output separate image streams to each display, which might involve activating additional display outputs or configuring the display controller to split its output across multiple connections.

One fundamental aspect of multi-monitor management is the concept of a virtual desktop. The operating system creates a single large coordinate space that encompasses all connected displays. You might have two 1920 by 1080 monitors arranged side by side, creating a virtual desktop that’s 3840 by 1080 pixels. Or you might stack them vertically for a 1920 by 2160 virtual desktop. The operating system allows you to arrange your monitors in various configurations, matching their physical arrangement on your desk, and creates the appropriate virtual desktop coordinate space.

The window manager must understand this multi-monitor virtual desktop. When an application creates a window or moves a window, its position is in these virtual desktop coordinates. The window manager determines which physical monitor or monitors the window appears on based on its position in the virtual desktop. A window might span multiple monitors if it’s large enough and positioned appropriately, or it might exist entirely on one monitor.

The operating system must handle cursor movement across multiple displays smoothly. As your mouse cursor moves from one display to another, the system must update its position in the virtual coordinate space and ensure it renders correctly on whichever display it currently inhabits. This seems simple but involves careful coordination, especially when displays have different resolutions or are arranged in complex configurations.

Different displays might have different characteristics beyond just resolution. One monitor might be a high-resolution 4K display while another is a standard 1080p display. The operating system must handle DPI scaling appropriately, rendering user interface elements at different sizes on different displays so they appear consistently sized physically, even though they occupy different numbers of pixels. This is particularly challenging when a window spans multiple displays with different DPI settings.

Refresh rate management becomes more complex with multiple monitors. If you have a 60Hz monitor and a 144Hz monitor, the operating system must coordinate display updates appropriately. It might need to update the 144Hz display more than twice as often as the 60Hz display. The window manager’s composition must account for this, potentially compositing and presenting frames at different rates for different displays.

Some modern systems support even more sophisticated multi-monitor features. You might designate one monitor as “primary,” which affects where new windows appear by default and where system UI elements like taskbars or menu bars initially appear. The operating system might support per-monitor color profiles, applying different color management to each display. And with the rise of mixed refresh rate setups, systems are implementing technologies that allow different monitors to update independently rather than synchronizing all displays to the slowest refresh rate.

Power management also intersects with multi-monitor support. When displays go to sleep or wake up, the operating system must handle this gracefully, preserving window positions and possibly migrating windows from a display that’s sleeping to one that’s active. When you disconnect a monitor, the system must move any windows that were on that display to remaining displays, and remember the configuration so it can restore window positions if you reconnect the display later.

The complexity of multi-monitor management is reflected in the settings interfaces operating systems provide. Users can typically control resolution and refresh rate per display, arrange displays in various configurations, choose which display is primary, set different backgrounds for each display, and configure how windows behave when moved between displays. All of these user-facing controls rely on sophisticated operating system infrastructure for managing multiple displays.

Hardware Acceleration and the GPU’s Role

Modern display management relies heavily on the graphics processing unit, or GPU, to handle the intensive computational workload of rendering graphics and compositing the final image. Understanding how the operating system leverages GPU hardware acceleration is essential to understanding contemporary display management.

The GPU is a specialized processor designed specifically for the parallel computations required in graphics rendering. While your computer’s main CPU might have four, eight, or sixteen cores designed for general-purpose computation, a modern GPU might have thousands of smaller, more specialized cores optimized for the specific mathematical operations common in graphics work.

The operating system coordinates with the GPU through several mechanisms. At the lowest level, the graphics driver provides kernel-mode code that can directly program the GPU hardware. This code sets up command buffers, which are sequences of commands that the GPU will execute. The driver submits these command buffers to the GPU, which then processes them asynchronously while the CPU continues with other work.

For display composition, the window manager acts as a client of the graphics stack, using graphics APIs to describe how window buffers should be combined into the final displayed image. It might describe a composition as a series of textured rectangles with specific blending modes, transformations, and other parameters. The graphics driver translates these descriptions into GPU commands that perform the actual composition work.

This GPU-accelerated composition enables visual effects that would be impractical to compute in software on the CPU. Smooth window animations involve interpolating window positions and properties over time and re-compositing the display many times per second. Semi-transparency requires blending pixels from multiple layers. Blur effects, which have become popular in modern user interface design, require examining many pixels around each point. All of these operations benefit tremendously from the GPU’s parallel processing capabilities.

The operating system must carefully manage GPU resources. Video memory on the graphics card is limited, and multiple applications might want to use the GPU simultaneously. The system implements GPU memory management, deciding what textures, buffers, and other data to keep in fast video memory versus slower system memory. It schedules GPU work from different applications, ensuring that each gets appropriate access while preventing any one application from monopolizing the GPU.

Power management for the GPU is another important consideration. Graphics hardware can consume significant power when running at full performance, but often doesn’t need to. When the display is showing mostly static content, the GPU can run at lower clock speeds to save energy. The operating system coordinates with the graphics driver to implement dynamic GPU frequency scaling, adjusting performance based on workload. It might also put the GPU into deeper sleep states when it’s not needed at all, such as when the display is turned off.

Modern operating systems also expose GPU capabilities to applications through various APIs. Applications can use these APIs to offload computation to the GPU, not just for graphics but for general parallel computing tasks. The operating system must arbitrate access to the GPU, ensuring that critical display composition work isn’t delayed by other GPU workloads, while still allowing applications to leverage this powerful hardware.

Some systems implement GPU virtualization, allowing multiple virtual machines to share a single GPU or even providing virtual GPUs that applications can use without direct hardware access. This requires sophisticated operating system support for isolating GPU resources, managing memory safely, and scheduling work efficiently.

The tight integration between the operating system and GPU hardware is why graphics driver updates can have such significant effects on performance and why issues with graphics drivers can cause system instability. The graphics driver operates at a very low level, with deep access to system resources, and bugs in the driver can potentially affect the entire system’s stability.

Display Protocols and Standards

The way data travels from your computer to your display involves standardized protocols that have evolved considerably over time. Understanding these display protocols helps explain certain aspects of display management and the capabilities modern systems support.

The earliest computer displays often used analog signals. VGA, which was standard for many years, transmitted separate analog voltage signals for red, green, and blue, along with synchronization signals. The graphics hardware converted digital pixel values to these analog voltages, and the monitor converted them back to digital values to control its pixels. This analog transmission introduced potential for signal degradation and made certain features difficult or impossible to implement.

Modern display connections are digital, transmitting pixel data as digital values directly. DVI was an early digital standard that eliminated the analog conversion step, providing cleaner images and supporting higher resolutions. HDMI became popular for consumer electronics, adding support for audio transmission alongside video and implementing content protection features. DisplayPort, designed specifically for computer displays, provides high bandwidth and advanced features like daisy-chaining multiple monitors.

These digital protocols work by encoding pixel data into a high-speed serial data stream. The display controller generates this stream according to precise timing requirements. Each protocol has specific encoding schemes and ways of embedding timing information, audio data, and other metadata within the signal.

The operating system must understand these protocols to configure the display controller appropriately. When you select a resolution and refresh rate, the system calculates the exact pixel clock frequency required, determines the appropriate blanking intervals, and configures the display controller to generate the correct signal timing. If the requested configuration exceeds what the connection can support, the system must either reduce quality or refuse the configuration.

Some modern protocols support adaptive sync, where the display’s refresh timing can vary dynamically. Rather than the display always refreshing at a fixed rate like 60Hz, it can refresh at variable rates determined by how quickly the graphics card is generating frames. This requires protocol support for variable timing and operating system support for coordinating with the display to achieve smooth frame delivery without tearing.

DisplayPort introduces concepts like Multi-Stream Transport, which allows multiple displays to be daisy-chained through a single connection. The operating system must understand this topology, communicating with displays downstream in the chain through the displays upstream, and managing bandwidth allocation across all connected displays.

USB-C has become increasingly common as a display connection, often carrying DisplayPort signals over USB-C connectors and cables. This alternate mode requires operating system support for detecting that a USB-C connection is carrying display signals and configuring the system appropriately. Some systems can charge from the same cable that carries display data, requiring coordination between display management and power management subsystems.

Wireless display technologies like Miracast or AirPlay present additional challenges. The operating system must encode video in real-time, transmit it over a network connection, manage latency and potential packet loss, and coordinate timing with the wireless display. These systems typically introduce more latency than wired connections and require significant CPU or GPU resources for video encoding.

The operating system abstracts most of these protocol details from applications and even from the user. When you connect a display, the system detects the connection type, queries the display’s capabilities, and presents you with appropriate configuration options. It handles all the low-level protocol details automatically, though it may provide advanced options for users who need fine control over timing or other parameters.

Resolution, Scaling, and DPI Management

One of the most important aspects of display management from the user’s perspective is how the operating system handles display resolution and scaling. This has become increasingly complex as displays have evolved from standard resolutions to high-DPI displays with pixel densities that exceed what human eyes can distinguish at normal viewing distances.

Display resolution refers to the number of pixels the display contains, typically expressed as width by height. Common resolutions include 1920 by 1080 (Full HD), 2560 by 1440 (QHD), and 3840 by 2160 (4K UHD). Higher resolutions provide more pixels, allowing for sharper images and more screen space for applications.

However, simply increasing resolution without other changes creates problems. If you take a traditional user interface designed for a 1920 by 1080 display and show it on a 4K display at 3840 by 2160 without any adjustment, everything becomes tiny. Text becomes hard to read, buttons become difficult to click, and the interface becomes unusable for many people. This is because the user interface elements are drawn using the same number of pixels, but those pixels are now much smaller on the higher-resolution display.

Operating systems solve this problem through DPI scaling, where DPI stands for “dots per inch.” The system determines the physical density of pixels on the display and scales user interface elements accordingly. On a high-DPI display, the system might render text and user interface elements at twice the size in pixels so they appear the same physical size as they would on a lower-DPI display.

The operating system obtains information about the display’s physical size through EDID data, allowing it to calculate the actual pixel density. A 27-inch monitor with 2560 by 1440 resolution has a lower pixel density than a 13-inch laptop screen with the same resolution, and the system can account for this by applying different scaling factors.

Implementing DPI scaling requires cooperation from applications. In the simplest approach, the operating system can render everything at higher resolution and scale it, but this can produce blurry results. Better results come from applications that are “DPI aware” and render their content directly at the appropriate scale, using higher-resolution assets when available and laying out their interfaces appropriately for the scaling factor.

The operating system provides APIs that applications can use to query the current DPI and scaling factor. Well-written applications use this information to choose appropriate font sizes, load high-resolution images and icons, and adjust their layouts. The system might report a scaling factor of 200 percent on a high-DPI display, and the application responds by doubling sizes throughout its interface.

Managing DPI becomes even more complex with multiple monitors at different pixel densities. You might have a laptop with a high-DPI built-in display and a lower-DPI external monitor. The operating system must handle applications that span both displays, potentially rendering different parts of the same window at different scales. Some systems handle this by scaling each window according to which monitor it primarily occupies, while others attempt more sophisticated per-monitor DPI awareness.

Some operating systems support fractional scaling, where the scaling factor might be 125 percent or 150 percent rather than simple integers like 100 percent or 200 percent. This provides more flexibility but introduces additional complexity, as the system might need to render at a higher resolution and then downscale slightly to achieve the fractional scaling factor.

The operating system’s settings interfaces allow users to adjust scaling manually if they prefer different sizes than what the system calculates automatically. This is useful for users with vision impairments who might want larger interface elements, or for users who prefer smaller elements to fit more content on screen.

Resolution and scaling also interact with other display management aspects. The window manager must account for scaling when compositing windows. Color management might need adjustment for different pixel densities. And text rendering, which we’ll discuss next, must adapt to produce readable results at various scales and pixel densities.

Text Rendering and Font Management

Text rendering is a specialized but crucial aspect of display management. Text is ubiquitous in computer interfaces, and the quality of text rendering significantly affects both the usability and the aesthetic appeal of the entire system. The operating system plays a central role in rendering text clearly and beautifully across different applications and display types.

At first glance, rendering text might seem simple: just draw the shapes of the letters. But text rendering is actually one of the most complex aspects of computer graphics. Fonts contain mathematical descriptions of letter shapes, typically as vector outlines that can be scaled to any size. The operating system must take these mathematical descriptions and convert them into pixels on the display, a process called rasterization.

The challenge is that text needs to be readable at small sizes, often just twelve or sixteen pixels tall, on displays with varying pixel densities. At these small sizes, naively rasterizing the vector outlines produces results that are blurry or have inconsistent thicknesses. Letter stems might appear different widths, or curves might look jagged.

To address this, operating systems implement font hinting and anti-aliasing. Font hinting uses instructions embedded in font files to adjust how letters are rasterized at small sizes, aligning important features like stems and curves to pixel boundaries to produce clearer results. Anti-aliasing uses partially lit pixels at the edges of letters to create the illusion of smoother curves and diagonals than the pixel grid actually allows.

Modern operating systems use sophisticated anti-aliasing techniques. Subpixel rendering, for example, takes advantage of the fact that each pixel on an LCD display is actually composed of separate red, green, and blue subpixels arranged horizontally. By controlling these subpixels individually, the system can effectively triple the horizontal resolution for text rendering, producing sharper results. However, subpixel rendering depends on the specific subpixel layout of the display, so the operating system must detect this layout and adjust rendering accordingly.

The operating system maintains a font rendering engine that applications use to render text. This engine handles loading font files, caching rasterized glyphs, managing font substitution when requested fonts aren’t available, and applying the appropriate anti-aliasing and hinting for the current display. Applications typically don’t render text themselves; instead, they ask the operating system to render text strings with specified fonts and sizes, and the system handles all the complex details.

Font management is another important aspect. The operating system maintains a collection of installed fonts and provides APIs for applications to enumerate available fonts and access them. It handles font family matching, where an application requests a bold or italic version of a font and the system locates the appropriate variant. It manages font fallback, where if a requested font doesn’t contain a particular character, the system automatically substitutes a different font that does.

High-DPI displays have significantly affected text rendering. With higher pixel densities, anti-aliasing becomes less critical because individual pixels are small enough that aliasing is less visible. However, the system must still ensure text is rendered at appropriate scales and with sufficient sharpness to take advantage of the available pixel density.

The operating system must coordinate text rendering with other display management aspects. The window manager must composite text properly, preserving anti-aliasing information. Color management must apply to text, ensuring text colors are accurate. And on systems with dynamic color schemes or dark modes, the text rendering engine must adapt to render readable text on varying backgrounds.

Different operating systems have developed distinct approaches to text rendering, leading to visible differences in how text appears across platforms. These differences reflect different priorities and philosophies about what makes text most readable and attractive, and they demonstrate how much sophisticated engineering goes into something that users often take for granted.

Power Management and Display Sleep

Display management intersects significantly with power management, as the display and graphics hardware can consume substantial power. The operating system must balance providing a responsive visual experience with conserving energy when possible.

Modern displays, especially large or high-resolution ones, can consume significant power. The operating system can reduce this power consumption by dimming the display when on battery power or when configured to save energy. Display brightness control is typically implemented through the graphics driver communicating with the display hardware via the display connection protocol. Some systems support adaptive brightness, using ambient light sensors to automatically adjust display brightness based on environmental lighting.

When the computer has been idle for a configured period, the operating system can put displays to sleep. This involves signaling the display to enter a low-power mode where it stops displaying images but remains ready to wake quickly. The operating system must coordinate this with the display controller, stopping the display signal and potentially powering down parts of the display output circuitry.

The graphics hardware itself also has power management features. When displaying mostly static content, the GPU doesn’t need to run at full performance. The operating system coordinates with the graphics driver to implement dynamic GPU frequency and voltage scaling, reducing power consumption when high performance isn’t needed. This requires careful monitoring of workload and quick response to increases in demand to maintain smooth performance.

Some systems implement advanced features like panel self-refresh, where the display maintains its current content using internal memory without requiring continuous updates from the computer. This allows the computer to power down display-related circuitry entirely when showing static content while the display remains on. The operating system must detect when content is static and coordinate with the display to enable this mode.

Multi-monitor setups complicate power management. The system might allow displays to sleep independently, requiring careful management of which displays are active and how to migrate windows or notify applications when displays change state. Some systems can even modify their refresh rate based on content, running displays at lower refresh rates when showing static content to save power.

The operating system must handle display wake gracefully. When you move the mouse or press a key, the system must quickly wake sleeping displays, restore their configuration, and resume normal operation. This requires coordinating between input handling, display management, and power management subsystems.

Modern systems also implement features like display power-off timers that are separate from system sleep. The displays might turn off after five minutes of inactivity while the computer itself continues running, perhaps performing background tasks. The system must maintain all display state during this time so it can restore displays immediately when the user returns.

Power management settings typically allow users to configure display sleep timeouts independently of system sleep timeouts, and these might differ between battery and AC power. The operating system must track these preferences and implement them correctly while handling edge cases like users who never want displays to sleep or systems that should never sleep while certain applications are running.

Handling Display Hot-Plugging and Configuration Changes

Users frequently connect and disconnect displays, particularly with laptops. The operating system must handle these dynamic configuration changes smoothly, maintaining usability throughout the process. This capability, often called hot-plugging, requires sophisticated coordination across multiple system components.

When you connect a new display, the hardware detects the connection and generates an interrupt that the operating system receives. The graphics driver responds by querying the display for its capabilities through the EDID exchange process. The operating system must then decide how to incorporate this new display into the current configuration.

Different systems have different default behaviors. Some might automatically extend the desktop onto the new display, creating additional screen space. Others might mirror the existing display onto the new one. The system might remember previous configurations and restore them automatically if it recognizes the specific display. All of these decisions require policy in the operating system about how to handle newly connected displays.

The window manager must adapt to configuration changes. If a new display extends the desktop, applications can now create windows on this additional space. If a display is disconnected, windows that were on that display must be migrated elsewhere. The system must preserve window positions when possible and provide reasonable fallback behavior when windows can’t be restored to their exact previous locations.

Applications might receive notifications when the display configuration changes. This allows them to adapt their behavior, perhaps moving content that was on a disconnected display or taking advantage of newly available screen space. The operating system provides APIs through which applications can monitor for configuration changes and query the current display layout.

Resolution and refresh rate changes, which users might make through system settings, require similar handling. The operating system must reconfigure the display controller with the new parameters, adjust the virtual desktop size if necessary, and notify applications of the change. During the brief moment while the display reconfigures, the system must handle the fact that the display might temporarily go black.

Some changes might fail. If you try to configure a resolution that the display claims to support but that the graphics hardware can’t actually generate, the system must detect this failure and either revert to the previous configuration or allow you to choose an alternative. Operating systems typically implement timeout mechanisms where if a new display configuration isn’t confirmed within a short period, the system automatically reverts to the previous working configuration.

The operating system must also handle malfunction scenarios. If a cable becomes partially disconnected or if a display develops a fault, the system might receive inconsistent information or lose communication with the display entirely. Robust display management requires gracefully handling these error conditions without crashing or leaving the system in an unusable state.

EDID data isn’t always correct or complete. Some displays report incorrect information about their capabilities, and some inexpensive displays don’t provide EDID data at all. The operating system must include fallback mechanisms and sometimes allow manual override of display parameters to work with these problematic displays.

Docking stations add another layer of complexity. A laptop might connect to a docking station that provides multiple display outputs, effectively connecting several displays simultaneously. The system must detect all these displays, configure them appropriately, and handle the fact that undocking will disconnect them all at once.

Video Playback and Hardware Decode Acceleration

Video playback is a specialized aspect of display management that involves unique challenges and optimizations. The operating system provides infrastructure that enables smooth, efficient video playback while minimizing CPU usage through hardware acceleration.

Video content is typically heavily compressed. A 4K video file might be manageable in size because it doesn’t store every pixel of every frame. Instead, it stores frames as compressed data using algorithms like H.264, H.265, VP9, or AV1. To display this video, the system must decompress each frame, a computationally intensive process that could overwhelm the CPU if done in software, especially for high-resolution video.

Modern graphics hardware includes dedicated video decode engines designed specifically for efficiently decompressing video. These engines can decode video streams much more efficiently than general-purpose CPU cores could. The operating system, through the graphics driver, provides access to these hardware decode capabilities.

Applications that play video can use operating system APIs to offload video decoding to the hardware. The application provides compressed video data to the system, which routes it to the hardware decoder. The decoder produces uncompressed frames, typically storing them in video memory where the graphics hardware can access them efficiently. The window manager then composites these decoded frames into the final display output.

This hardware-accelerated path provides multiple benefits. It reduces CPU usage significantly, allowing smooth video playback even on modest hardware and freeing CPU resources for other tasks. It reduces power consumption since dedicated video decode hardware is more energy-efficient than performing the same work on CPU cores. And it enables smooth playback of high-resolution, high-frame-rate video that might be impossible to decode in software in real-time.

The operating system must manage video decoder resources. Hardware decoders are limited resources; a GPU might only be able to decode a certain number of video streams simultaneously. The system must arbitrate access when multiple applications want to decode video, and it must handle fallback to software decoding if hardware resources are exhausted.

Different video formats require different decoder capabilities. A GPU might support hardware decode for H.264 but not for newer formats like AV1. The operating system provides APIs through which applications can query what hardware decode capabilities are available and select appropriate formats accordingly.

Video playback also involves timing considerations. Video has an inherent frame rate, and frames must be presented at the correct times to maintain smooth playback and proper synchronization with audio. The operating system provides timing mechanisms that applications use to schedule frame presentation accurately.

Some systems implement technologies that optimize video playback specifically. For example, when a video is playing in full-screen mode, the system might bypass the normal compositing path and present video frames directly to the display, reducing latency and eliminating unnecessary copying of pixel data. This requires coordination between the video playback subsystem, the window manager, and the display controller.

Protected video content introduces additional requirements. Content providers often require that video remain protected throughout the playback pipeline to prevent copying. The operating system must implement secure video paths where video data remains encrypted or otherwise protected as it flows through the system, only being decrypted at the last moment before being sent to the display. This requires integration between content protection systems, the graphics driver, and display hardware.

The operating system also handles video scaling. If video is being displayed at a different resolution than its native resolution, the system can leverage graphics hardware to perform high-quality scaling. This is especially important for displaying lower-resolution video on high-resolution displays without introducing excessive blurriness or blockiness.

Accessibility Features in Display Management

Accessibility is an important consideration in display management, as the operating system must provide capabilities that make displays usable for people with various disabilities or limitations. Many of these accessibility features require deep integration with display management subsystems.

For users with low vision, the operating system provides magnification capabilities. Screen magnifiers allow users to zoom in on portions of the display, seeing an enlarged view of whatever is under their cursor or focus. Implementing smooth, high-quality magnification requires cooperation from the window manager and compositor. The system must render content at high resolution before applying magnification to maintain clarity, and it must update the magnified view smoothly as the user moves around the screen.

Color and contrast adjustments help users who have difficulty distinguishing certain colors or who need higher contrast to read content comfortably. The operating system can apply color filters that shift the entire display’s color palette, implement high-contrast modes that adjust colors system-wide, or invert colors for users who prefer light text on dark backgrounds. These adjustments typically happen during the final composition stage, allowing them to affect all displayed content uniformly.

For users with photosensitivity or who need to reduce eye strain, systems implement features like night modes or blue light filters that adjust the display’s color temperature, typically reducing blue light in the evening. These features require time-aware adjustment of color throughout the display pipeline.

Screen readers, which provide audio descriptions of on-screen content for blind users, require deep integration with display management. The system must maintain an accessibility tree that describes the structure and content of what’s displayed, allowing screen readers to understand and describe the interface. Applications contribute to this tree, and the window manager must coordinate accessibility information from multiple applications.

Cursor enhancements help users who have difficulty seeing or tracking the standard mouse cursor. The operating system can provide larger cursors, high-contrast cursors, or cursor trails that leave a temporary trace as the cursor moves. Some systems implement cursor highlighting that displays a growing circle around the cursor when activated, helping users locate it on screen.

Text-to-speech and speech recognition systems that help users interact with the computer without typing require access to the text content of displayed elements. The operating system must provide APIs that allow these systems to extract text from applications and monitor changes to displayed content.

Animation and motion controls benefit users who are sensitive to motion or who find animations distracting. The operating system can reduce or disable animations throughout the interface, requiring the window manager and applications to honor these preferences.

Closed captioning support for video content requires coordination between video playback subsystems and display management to ensure captions are rendered clearly and synchronized properly with video content.

All of these accessibility features must be implemented efficiently enough that they don’t significantly impact system performance, and they must be designed carefully to remain useful even as display technology and interface design evolve. The operating system must provide clear controls for enabling and configuring accessibility features, making them discoverable to users who need them.

Looking Forward: The Future of Display Management

Display management continues to evolve as display technology advances and user expectations increase. Understanding where display management is heading helps contextualize the current state and appreciate the ongoing complexity of this system component.

Higher resolution displays continue to emerge. 8K displays, with four times the pixels of 4K, are becoming available, and even higher resolutions are likely in the future. Operating systems must evolve to handle the enormous data requirements of these displays efficiently, managing the massive frame buffers and ensuring smooth performance despite the increased pixel counts.

Variable refresh rate technology is becoming more sophisticated. Beyond just gaming, displays that can adjust their refresh rates dynamically based on content could improve both performance and power efficiency. The operating system must coordinate more closely with display hardware to take full advantage of these capabilities.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) displays, which can reproduce a much wider range of brightness levels than traditional displays, are becoming more common. Operating systems must evolve their color management and composition pipelines to handle HDR content correctly, managing the tone mapping required to display HDR content on SDR displays and vice versa, and providing appropriate controls for content creators and consumers.

Foldable and flexible displays introduce new challenges. How should the operating system handle a display that can change its physical size and shape? How should it transition content when a device unfolds from phone to tablet form factor? Display management must become more dynamic and adaptive.

Augmented and virtual reality displays require fundamentally different display management approaches. The operating system must render separate images for each eye, handle very high frame rates to prevent motion sickness, implement low-latency tracking of head movements, and coordinate with specialized display hardware. As these technologies become more mainstream, operating systems will need to integrate their display management more completely.

Wireless displays are improving, potentially reducing or eliminating the need for display cables. Operating systems must handle wireless display connections seamlessly while managing the additional latency, potential interference, and power requirements these connections introduce.

Machine learning might play an increasing role in display management. The system could learn user preferences for display configuration, automatically adjusting settings based on context, or use ML to enhance image quality, upscale content, or predict what the user will want to see next to pre-render content speculatively.

Power efficiency remains a constant concern. As displays become larger and higher resolution, they consume more power. Operating systems must continue to develop more sophisticated power management, finding ways to reduce energy consumption while maintaining the visual quality and responsiveness users expect.

The increasing integration of computing into various devices means display management must work across a wider range of form factors and use cases. From smartwatches to large wall-mounted displays, from car dashboards to industrial controls, operating systems must adapt their display management to different contexts while maintaining consistent capabilities.

Conclusion: The Hidden Complexity Behind Every Pixel

When you look at your computer screen, you’re seeing the result of an extraordinarily complex collaboration between hardware and software that most users never think about. Every pixel you see represents countless calculations, carefully orchestrated by your operating system to transform abstract data into visual information you can understand and interact with.

We’ve explored how operating systems manage displays through multiple layers of abstraction, from high-level window management through graphics APIs and drivers to low-level hardware control. We’ve seen how frame buffers store the image that becomes what you see, how the window manager composes multiple applications’ visual content into a cohesive whole, and how the graphics driver translates abstract rendering commands into hardware-specific instructions. We’ve examined how displays communicate their capabilities, how color management ensures accurate color reproduction, and how the system handles multiple displays with different characteristics.

Display management touches virtually every aspect of the computing experience. The quality of text rendering affects how easily you can read documents and web pages. The smoothness of animations impacts how responsive the interface feels. The accuracy of colors matters for photo editing and design work. The efficiency of display management affects battery life and system performance. And accessibility features built into display management can make the difference between a computer that’s usable and one that isn’t for people with disabilities.

The sophistication of modern display management is testament to the ongoing evolution of operating systems. Early systems had simple display management that directly wrote pixels to a frame buffer. Today’s systems implement complex composition, leverage powerful graphics hardware, manage multiple high-resolution displays simultaneously, handle dynamic configuration changes gracefully, and provide sophisticated capabilities for accessibility and power management.

As display technology continues to advance, with higher resolutions, wider color gamuts, variable refresh rates, HDR capabilities, and new form factors, operating system display management will continue to evolve. The fundamental challenge remains the same: translating the abstract, digital world inside the computer into visual information that humans can perceive and understand. But the sophistication with which operating systems meet this challenge grows continuously.

The next time you move a window, watch a video, or simply read text on your screen, take a moment to appreciate the remarkable complexity happening behind the scenes. Hundreds of thousands of lines of code, multiple layers of sophisticated software, specialized hardware, and careful coordination make those pixels light up in exactly the right colors at exactly the right times. Your operating system’s display management makes it all look effortless, but the reality is anything but. It’s a triumph of engineering that we can take for granted precisely because it works so well.