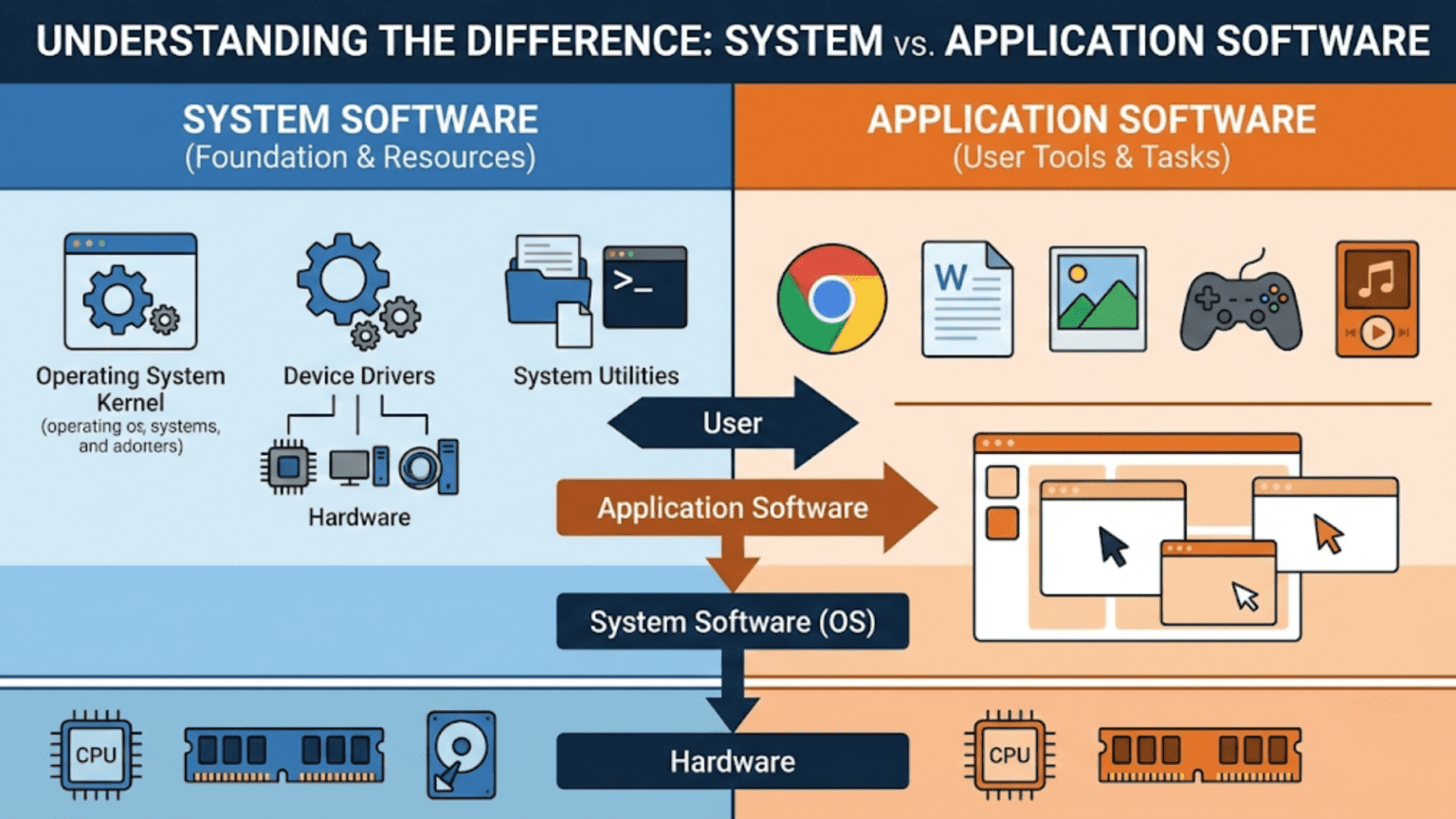

System software is software that manages and operates computer hardware, providing the foundation on which application software runs—it includes operating systems, device drivers, firmware, and utilities that control system resources and hardware. Application software, in contrast, performs specific tasks for users—like word processing, web browsing, or photo editing—and depends on system software to interact with hardware. The key distinction is purpose: system software serves the machine and infrastructure, while application software serves the user.

When you sit down at your computer to write a report, browse the internet, or edit photos, you’re interacting with application software—programs designed specifically to help you accomplish those tasks. But beneath every application you use, invisible layers of software manage the hardware, allocate resources, enforce security, and provide the services that make those applications possible. This foundational layer is system software, and understanding the distinction between system software and application software is one of the most fundamental concepts in computer science—one that shapes how computers are designed, how software is developed, and how we understand the relationship between users, programs, and hardware.

The distinction between system software and application software isn’t just a conceptual categorization exercise; it has real implications for how software is built, installed, secured, and maintained. System software runs with elevated privileges and direct hardware access that application software doesn’t have. Updates to system software require more caution because failures can make the entire computer unusable. System software typically ships with the operating system or hardware while application software is chosen and installed by users. Security vulnerabilities in system software have far more serious consequences than those in application software. Understanding where the boundary lies—and why it exists—helps demystify how computers work and why they work the way they do. This comprehensive guide explores both categories in depth, examining what defines each type, the key differences between them, how they interact, the subcategories within each, and why this fundamental distinction shapes everything from computer architecture to software security.

Defining System Software

System software encompasses all programs that manage, control, and coordinate computer hardware and provide the infrastructure on which other software operates.

The defining characteristic of system software is its relationship to the machine itself rather than to user tasks. System software exists to make the computer function—to translate user intentions into hardware operations, to allocate scarce resources fairly, to protect processes from interfering with each other, and to present hardware capabilities through standardized interfaces. Users rarely interact with system software directly; instead, they experience its effects through the reliable, consistent behavior of the hardware and the applications built on top of it.

The operating system is the most prominent category of system software, serving as the master coordinator of all computer resources. The OS manages the CPU (scheduling which process runs when), memory (allocating RAM to processes, managing virtual memory), storage (implementing file systems, handling disk I/O), input/output devices (through device drivers), and security (enforcing access controls and process isolation). Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS, Android, and ChromeOS are all operating systems—different implementations of the same fundamental system software concept.

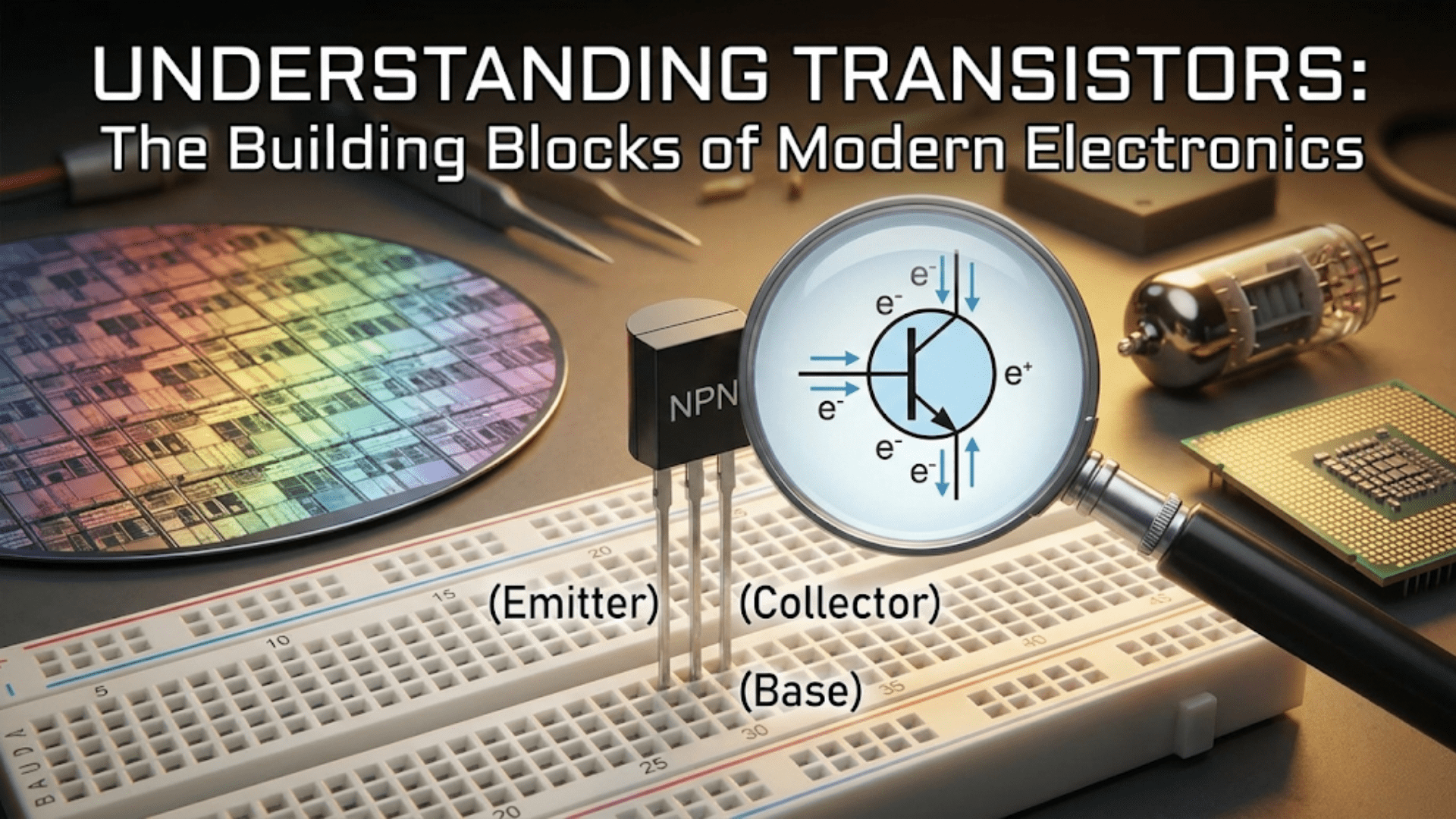

Device drivers are specialized system software components that enable the OS to communicate with specific hardware devices. Every piece of hardware—graphics cards, network adapters, printers, keyboards, storage controllers—requires a driver that understands the device’s specific command interface and translates generic OS requests into device-specific operations. Without a driver, the OS has no way to communicate with hardware. Drivers run with kernel-mode privileges, giving them direct hardware access but also making driver bugs potentially catastrophic.

Firmware sits even lower in the software hierarchy, stored in non-volatile memory on hardware devices themselves. UEFI/BIOS firmware initializes hardware at power-on, performs the Power-On Self-Test (POST), and loads the bootloader. Network card firmware implements the network protocol stack in hardware. SSD controllers have firmware managing flash memory wear leveling and error correction. Firmware is system software so fundamental that it lives in the hardware itself.

System utilities are tools that maintain, configure, and optimize the computer system. Disk formatters, backup utilities, defragmenters, system monitors, compression tools, and security scanners are all system utilities—they operate at the system level, often with elevated privileges, to maintain system health. These utilities serve the computer’s needs rather than performing user-facing productive tasks.

Bootloaders are system software that run before the OS, loading it from storage into memory and transferring control. GRUB (Grand Unified Bootloader) on Linux, Windows Boot Manager, and Apple’s iBoot on iOS/macOS all perform this critical initialization role. Without a bootloader, the OS couldn’t start.

The shell or command interpreter (bash, PowerShell, zsh) occupies an interesting middle ground—it’s a user interface to the system, allowing direct system management. Shells are typically considered system software because they primarily expose system functionality rather than performing user-facing productive tasks, though this classification is debated.

Defining Application Software

Application software encompasses programs designed to help users perform specific productive tasks, solve particular problems, or achieve defined goals.

The defining characteristic of application software is its orientation toward user needs and goals rather than system management. Application software is what users actually want to accomplish with computers—writing documents, communicating, calculating, creating, entertaining, analyzing. Applications are chosen by users based on what they need to accomplish, unlike system software which ships with hardware or OS and isn’t selected for its specific capabilities.

Productivity applications help users create, organize, and communicate. Word processors (Microsoft Word, Google Docs, LibreOffice Writer), spreadsheets (Excel, Google Sheets), presentation tools (PowerPoint, Keynote), and email clients (Outlook, Thunderbird) are the classic productivity application category. These applications are chosen specifically for their features and capabilities by users who need to accomplish specific types of work.

Creative applications support artistic and content creation tasks. Photo editors (Photoshop, GIMP, Lightroom), video editors (Premiere Pro, Final Cut, DaVinci Resolve), audio editors (Audacity, Logic Pro), 3D modeling tools (Blender, Maya), and graphic design tools (Illustrator, Inkscape) all serve creative professionals and hobbyists. These applications leverage system resources intensively but are entirely focused on enabling users to create specific types of content.

Communication applications enable people to connect and share information. Web browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge), email clients, messaging applications (Slack, Teams, WhatsApp), video conferencing tools (Zoom, Google Meet), and social media clients all fall in this category. Their purpose is connecting people and facilitating information exchange.

Entertainment and media applications provide experiences rather than productivity. Games, music players, video streaming clients, podcast apps, ebook readers, and media centers are entertainment applications chosen for the experiences they deliver.

Business and enterprise applications serve organizational needs beyond individual productivity. Database management systems used by applications (distinct from the DBMS engine itself), CRM systems, ERP systems, accounting software, inventory management, and industry-specific tools all serve business processes.

Development tools occupy a notable position—they’re application software (chosen by developers for their capabilities, focused on user tasks) but their purpose is creating other software, including potentially system software. IDEs, compilers, debuggers, version control clients, and build systems are applications serving the specialized user task of software development.

Key Differences Between System and Application Software

Multiple dimensions distinguish system software from application software, each reflecting the fundamentally different purposes these categories serve.

Purpose and audience represent the most fundamental difference. System software serves the computer system itself, enabling it to function and manage resources. Application software serves users, enabling them to accomplish goals. This purpose difference shapes every other characteristic. System software priorities are reliability, performance, and compatibility; application software priorities are functionality, usability, and features serving user needs.

Hardware interaction differs dramatically between the categories. System software interacts directly with hardware through privileged instructions, memory-mapped I/O, and direct DMA access. Device drivers communicate directly with hardware registers; the kernel manages physical memory pages; firmware programs hardware controllers directly. Application software never directly touches hardware—instead, it makes requests through system calls and OS APIs, and system software performs the actual hardware interaction on its behalf. This indirection through controlled interfaces is both a security and reliability measure.

Privilege levels reflect the hardware interaction difference. System software (kernel, drivers) runs in kernel mode (ring 0 on x86), with access to all instructions and memory. Application software runs in user mode (ring 3), restricted from executing privileged instructions or accessing protected memory. This hardware-enforced privilege separation prevents application bugs or malicious code from directly corrupting system state.

Installation and distribution differ significantly. System software typically comes pre-installed with the operating system or hardware—Windows includes its own system utilities, drivers, and management tools; macOS includes its own system frameworks; hardware ships with firmware pre-flashed. Users install application software separately, choosing from available options based on their needs. The exception is OEM software bundling where manufacturers pre-install application software, which often feels like system software to users but is architecturally application software.

Dependency relationships flow in one direction. Application software depends on system software—applications require an OS to run, and the OS requires drivers to communicate with hardware. System software doesn’t depend on application software to function; the OS works correctly whether or not any applications are installed. This asymmetric dependency is fundamental: removing all application software leaves a functioning (if empty) system; removing system software renders applications non-functional.

Update consequences reflect the criticality difference. Failed application software updates might break a specific program, which can be uninstalled and reinstalled or reverted. Failed system software updates—kernel panics, driver failures, bootloader corruption—can render the entire computer unbootable. This asymmetric risk means system software updates require more testing, more cautious rollout, and more careful recovery mechanisms. Windows Update, macOS Software Update, and Linux package managers all treat system and application updates with different levels of caution.

Security implications differ substantially. Vulnerabilities in system software can compromise the entire system—a kernel vulnerability allows complete system takeover, a driver vulnerability can bypass all security measures. Vulnerabilities in application software are serious but typically limited to that application’s scope and the permissions of the user running it. This difference in security impact is why OS and driver vulnerabilities are treated with extreme urgency while application vulnerabilities, while important, don’t typically require emergency patches.

Development environment differences reflect privilege requirements. System software development requires specialized knowledge of hardware interfaces, kernel internals, and low-level programming. Kernel development uses C or Rust and requires understanding memory management, interrupt handling, and hardware protocols. Application development uses any of hundreds of languages and frameworks, building on abstractions provided by system software rather than working at the hardware level.

The Interaction Between System and Application Software

System and application software don’t operate in isolation—they interact continuously through defined interfaces that allow applications to request system services while maintaining the separation between privileged and unprivileged code.

System calls are the fundamental interface between application and system software. When an application needs to read a file, create a network connection, allocate memory, or perform any operation requiring hardware access, it executes a system call—a controlled transition from user mode to kernel mode where the OS performs the requested operation on the application’s behalf. System calls are numbered and named (open(), read(), write(), socket() on Unix; NtCreateFile(), NtReadFile() on Windows NT), forming the API through which all application-system interaction occurs.

System libraries and frameworks wrap system calls in higher-level, more convenient interfaces. The C standard library (libc), Windows API (Win32), and macOS Cocoa frameworks translate programmer-friendly function calls into appropriate system calls. A programmer calling fopen() to open a file doesn’t manually invoke the open() system call—the C library handles that translation. These libraries are distributed with the OS as part of the system software layer even though they run in user mode.

Hardware abstraction layers provided by operating systems allow applications to work with hardware without knowing device specifics. The Windows driver model and Linux driver framework present unified interfaces to applications—an audio application uses standard audio APIs regardless of whether the sound hardware is from Realtek, Creative, or any other manufacturer. System software (drivers) handles device-specific differences; application software works with abstract, standardized interfaces.

Events and notifications flow from system software to applications, informing them about hardware events and system state changes. USB device connection/disconnection events, network status changes, power state transitions, and display configuration changes are all delivered to interested applications through OS notification systems. Applications register interest in specific events; system software delivers them as they occur.

Shared services provided by system software benefit all applications simultaneously. The file system cache, maintained by the OS kernel, caches frequently accessed file data in RAM, benefiting every application that reads files. DNS caching, font caching, and graphics composition all represent system services that multiple applications benefit from without each needing to implement them independently.

Gray Areas and Evolving Boundaries

The distinction between system software and application software is not always clear-cut, with various software components occupying ambiguous middle ground.

System applications ship with operating systems and perform administrative tasks but aren’t core OS components. Windows Task Manager, macOS Disk Utility, and Linux GNOME System Monitor are technically applications (user-mode programs with graphical interfaces focused on user tasks) but are so closely associated with system management that they feel like system software. These “system applications” exist in a conceptual gray area.

Middleware sits between OS and applications, providing services like database connectivity, message queuing, application servers, and web servers. A MySQL database server or an Apache web server runs as system software from the perspective of applications that depend on it—providing infrastructure services—but is clearly application software from the OS perspective, running in user mode with no special privileges. The classification depends on perspective.

Runtime environments for languages like Java (JVM), Python interpreter, .NET runtime, and Node.js are application software that provides a platform for other applications. To Java applications, the JVM looks like system software—providing garbage collection, class loading, and JIT compilation as infrastructure services. But to the OS, the JVM is just another user-mode application.

Hypervisors virtualize hardware for virtual machines, occupying a unique position. Type 1 hypervisors (VMware ESXi, Hyper-V bare-metal) run directly on hardware below the OS—clearly system software. Type 2 hypervisors (VirtualBox, VMware Workstation) run as applications on top of an OS—they’re application software that happens to create virtual system software environments.

Embedded systems often blur the distinction fundamentally. A router’s firmware handles both system functions (managing hardware resources, network protocols) and application functions (providing configuration interfaces, implementing routing logic) in a single integrated software stack without a clear OS/application separation.

Cloud computing further complicates classification. Cloud service providers offer managed versions of databases, message queues, and other traditionally middleware components as services. From the perspective of applications consuming these services, they function like system software—infrastructure that applications depend on. But they run as application software on the provider’s systems.

Why the Distinction Matters

Understanding the system/application software distinction has practical implications across multiple domains.

Security architecture depends on the distinction. OS security models are built around the principle that system software is trusted and application software is untrusted. Privilege levels, access controls, sandboxing, and capability systems all implement this trust model. Security engineers designing system security must understand which software runs with which privileges and why.

Performance optimization strategies differ by software type. Application performance optimization focuses on algorithms, data structures, and efficient use of OS services. System software performance optimization focuses on reducing overhead, minimizing system call frequency, avoiding unnecessary copying, and efficiently managing hardware resources. The techniques and tools differ substantially.

Debugging approaches differ by privilege level. User-mode application debuggers (gdb, lldb, Visual Studio debugger) attach to processes and inspect their state. Kernel debuggers (WinDbg in kernel mode, kgdb on Linux) work at the OS level with visibility into kernel state but much more risk—a mistake in a kernel debugging session can crash the entire system. This difference in debugging approach reflects the privilege difference between system and application software.

Licensing and distribution models often differ. System software is frequently open-source (Linux kernel, many drivers, firmware for various devices) because the infrastructure benefits everyone. Application software is commonly commercial with per-user or per-seat licensing. This isn’t universal—commercial operating systems (Windows, macOS) and open-source applications exist—but the trend reflects the different economic models around infrastructure versus user-facing functionality.

Career paths in software development split along this boundary. Systems programmers work on kernels, drivers, embedded firmware, and performance-critical infrastructure in C, C++, Rust, and assembly. Application developers work on user-facing software in higher-level languages using OS-provided frameworks. These require different skills, knowledge, and mindsets—though expertise in both is rare and valuable.

Conclusion

The distinction between system software and application software represents one of the most fundamental conceptual divisions in computing, reflecting the layered architecture that makes modern computers both powerful and manageable. System software—operating systems, device drivers, firmware, bootloaders, and system utilities—provides the invisible infrastructure that makes hardware usable and applications possible. Application software—the word processors, browsers, games, and creative tools users actually interact with—leverages that infrastructure to serve human needs and goals.

This distinction matters practically in security (system software vulnerabilities are more severe), reliability (system software failures are more catastrophic), development (different skills and approaches), performance (different optimization strategies), and understanding (knowing why computers work as they do). The layers of abstraction that system software provides—hiding hardware complexity behind consistent interfaces—enable application developers to focus on user needs rather than hardware details, making software development more productive and applications more portable across different hardware configurations.

As computing evolves with cloud services blurring traditional boundaries, containerization changing how system services are packaged and delivered, and new hardware architectures requiring new system software approaches, the fundamental distinction between software that serves the machine and software that serves the user remains a clarifying framework. Understanding this distinction, how the two categories interact, and where the boundaries are fuzzy provides essential context for understanding computers, software, and the remarkable ecosystem of both that makes modern computing possible.

Summary Table: System Software vs. Application Software

| Characteristic | System Software | Application Software |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Manage hardware, provide infrastructure for other software | Enable users to perform specific tasks and achieve goals |

| Who It Serves | The computer system itself | The user |

| Interaction with Hardware | Direct (kernel mode, privileged instructions, DMA) | Indirect (through system calls and OS APIs) |

| Privilege Level | Kernel mode (Ring 0) for core components | User mode (Ring 3) |

| Examples | Operating systems, device drivers, BIOS/UEFI, bootloaders | Word processors, browsers, games, photo editors |

| Installation | Pre-installed with OS or hardware | Chosen and installed by users |

| Dependencies | Depends on hardware firmware; kernel depends on nothing above it | Depends on system software and OS APIs |

| Update Risk | High — failures can make system unbootable | Lower — failures affect specific application only |

| Security Impact of Vulnerabilities | Critical — can compromise entire system | Serious — typically limited to application scope |

| Primary Languages | C, C++, Rust, Assembly | Any language; Python, Java, JavaScript, C#, Swift, etc. |

| User Interaction | Minimal — users rarely interact directly | Direct — designed for user interaction |

| Performance Optimization Focus | Minimize overhead, efficient hardware use, kernel paths | Algorithms, data structures, efficient use of OS services |

| Distribution Model | Often open-source; bundled with OS/hardware | Often commercial; chosen by users from marketplace |

Categories of Each Software Type:

| System Software Categories | Examples | Application Software Categories | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows, Linux, macOS, iOS, Android | Productivity | Word, Excel, Google Docs, LibreOffice |

| Device Drivers | GPU drivers, NIC drivers, printer drivers | Creative | Photoshop, Premiere, Blender, Audacity |

| Firmware | UEFI/BIOS, SSD controller firmware, NIC firmware | Communication | Chrome, Firefox, Slack, Zoom, Outlook |

| Bootloader | GRUB, Windows Boot Manager, Apple iBoot | Entertainment | Games, Spotify, Netflix app, VLC |

| System Utilities | Disk Utility, Task Manager, Backup tools | Business/Enterprise | CRM, ERP, accounting, inventory systems |

| Shell/CLI | Bash, PowerShell, zsh, cmd.exe | Development Tools | VS Code, IntelliJ, Eclipse, PyCharm |

| System Libraries | libc, Win32 API, Cocoa frameworks | Education | Khan Academy, Duolingo, Coursera apps |

| Hypervisors (Type 1) | VMware ESXi, Hyper-V bare-metal | Database Clients | MySQL Workbench, pgAdmin, DB Browser |

| Middleware (infrastructure) | Apache HTTP Server, nginx, message queues | Utilities (user-focused) | Archive managers, file converters, calculators |