The clipboard is an operating system service that temporarily stores data when users copy or cut content, making it available for pasting into the same or different applications. Operating systems manage the clipboard by maintaining a buffer of copied data in memory, supporting multiple data formats simultaneously (text, images, formatted content, files) so receiving applications can access the format most useful to them, and providing APIs that applications use to read from and write to this shared data exchange mechanism.

The simple act of copying text from a website and pasting it into a document seems almost trivially mundane—yet beneath that familiar Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V keyboard shortcut lies a surprisingly sophisticated operating system service that coordinates data exchange between applications that may have been written by entirely different developers with no knowledge of each other. The clipboard mediates this data sharing, managing a temporary buffer that holds copied content in multiple formats simultaneously, negotiating format compatibility between source and destination applications, and providing the infrastructure that makes cut-copy-paste one of the most universally understood and relied-upon computing interactions. Without a well-designed clipboard service, modern productivity workflows would be fundamentally impaired—copying information between applications is such a core computing activity that its absence would be immediately and profoundly felt.

Operating systems implement clipboard functionality as a system service precisely because clipboard data needs to be accessible across application boundaries, persisting after the copying application might close and being available to any application that wants to receive it. This cross-application nature means clipboard management can’t be handled by individual applications independently—it requires OS-level infrastructure to maintain the shared data buffer, manage concurrent access, support format negotiation between applications with different data handling capabilities, and increasingly maintain clipboard history that survives individual copy operations. Each major operating system—Windows, macOS, and Linux—implements clipboard functionality differently, reflecting different architectural philosophies and historical development paths, yet all solve the same fundamental challenge of enabling seamless data exchange between applications. This guide explores how clipboard systems work, the technical mechanisms behind copy and paste, multi-format clipboard data, clipboard history features, security considerations, cross-platform differences, and the specialized clipboard behaviors developers need to understand when building applications.

How the Clipboard Works Fundamentally

The clipboard is a transient shared memory area managed by the operating system, accessible to all running applications through dedicated APIs.

When you copy content, your application prepares the selected data and places it in the clipboard buffer maintained by the OS. The actual copying operation involves the OS taking ownership of this data, making it accessible to other applications. The source application notifies the OS that data is available, and the OS maintains it until either new content is copied (replacing the previous content) or the system shuts down.

Clipboard ownership is an important concept. Only one application “owns” the clipboard at a time—the application that most recently placed data there. The OS tracks clipboard ownership and can notify applications when ownership changes (when another application copies something new). Applications interested in clipboard changes can subscribe to clipboard change notifications, enabling features like clipboard managers that monitor and record clipboard history.

Data representation flexibility is fundamental to clipboard design. When you copy a formatted paragraph from Word, what format should the clipboard store? Plain text (useful for pasting into plain text editors), rich text (preserving formatting for compatible applications), HTML (useful for web applications), or Word’s native format (preserving everything for pasting back into Word)? The solution is to store multiple representations simultaneously—the same clipboard content is available in several formats, and the receiving application selects whichever format it can best use. This multi-format approach is why pasting from a formatted document into a plain text editor gives you plain text—the editor requests the plain text format and receives it, ignoring rich format representations.

Lazy data provision is an optimization used by some clipboard implementations. Rather than immediately serializing all requested formats when copying (which could be expensive for large or complex content), the source application registers which formats it can provide and only actually generates the data when a specific format is requested. When you paste in the destination application, the OS asks the source application for the specific format needed, which generates it on demand. This lazy approach reduces work when many formats are registered but only one is actually needed.

The clipboard’s temporary nature means clipboard contents are typically lost when the system shuts down, when the source application closes (in some implementations), or when new content is copied. This ephemerality is by design for simple use cases—the clipboard is a short-term exchange medium, not persistent storage. Clipboard history features overcome this limitation by maintaining a history of recent clipboard contents beyond just the most recent copy operation.

Windows Clipboard Architecture

Windows implements a comprehensive clipboard system with rich format support, history features, and developer APIs that have evolved through multiple Windows generations.

The Windows clipboard is managed by the Win32 subsystem and accessible through a set of Win32 API functions. Applications open the clipboard with OpenClipboard(), place data using SetClipboardData() with format identifiers, and close with CloseClipboard(). Reading uses OpenClipboard(), GetClipboardData() specifying a format, and CloseClipboard(). This explicit open-close model serializes clipboard access, preventing simultaneous modifications by multiple applications.

Standard clipboard formats are pre-defined format identifiers that Windows recognizes. CF_TEXT stores null-terminated ANSI text, CF_UNICODETEXT stores Unicode text, CF_BITMAP stores device-independent bitmaps, CF_HDROP stores file paths for file copy operations, CF_HTML stores HTML content with header information, CF_RTF stores Rich Text Format content, and many others. These standard formats ensure any Windows application using them can interoperate without needing knowledge of each other’s internal data formats.

Custom clipboard formats allow applications to exchange proprietary data types. Applications register custom format names with RegisterClipboardFormat(), receiving a format ID they can use for SetClipboardData() and GetClipboardData(). If two applications use the same format name, they receive the same ID, enabling data exchange through shared format conventions. This mechanism allows specialized applications to exchange rich data—a drawing application and a presentation application might share a custom vector graphics format while also providing standard bitmap and text representations as fallbacks.

The clipboard viewer chain (superseded in modern Windows by clipboard format listeners) allowed applications to monitor clipboard changes by registering as part of a chain of viewers. Modern Windows provides AddClipboardFormatListener() for applications to receive WM_CLIPBOARDUPDATE messages when clipboard contents change, without the complexity and fragility of the older viewer chain. Third-party clipboard manager applications use this mechanism to capture and store clipboard history.

Windows Clipboard History (Win+V) was introduced in Windows 10 October 2018 Update, providing a built-in multi-item clipboard history storing up to 25 recent clipboard entries. Users press Win+V to open the clipboard history panel, see recent items as text or image thumbnails, and click any item to paste it. Clipboard History can be synced across devices via Microsoft account, allowing copying on one Windows device and pasting on another. Individual items can be pinned (preventing eviction when the 25-item limit is reached), deleted, or cleared entirely. Clipboard History must be enabled in Settings > System > Clipboard before first use.

Windows also implements clipboard for Universal Windows Platform (UWP) applications through the Windows.ApplicationModel.DataTransfer.Clipboard API, which provides similar functionality with a modern API design. Share functionality in UWP extends clipboard-like data exchange to sharing between applications through a standardized Share UI that applications can both offer and receive from.

macOS Clipboard Architecture

macOS implements clipboard functionality through the pasteboard system, which extends the clipboard concept with named, persistent pasteboards for different use cases.

The general pasteboard (NSPasteboard.general) is the primary clipboard, equivalent to what users think of as “the clipboard.” It stores the most recently copied item and is what pastes when pressing Cmd+V. The pasteboard API is built on the concept of pasteboard items, each of which can provide data in multiple UTI (Uniform Type Identifier) formats.

UTIs (Uniform Type Identifiers) are Apple’s type system that extends traditional MIME types. Rather than ad-hoc format names, UTIs use reverse-DNS notation to create globally unique type identifiers: public.plain-text for plain text, public.html for HTML, com.adobe.pdf for PDF, public.image for images, com.microsoft.word.doc for Word documents. UTIs support type hierarchies—public.plain-text conforms to public.text which conforms to public.data, so an application accepting any text type automatically accepts plain text. This hierarchy enables richer format negotiation than flat format ID systems.

Named pasteboards extend beyond a single clipboard. The find pasteboard (NSPasteboard.find) stores the most recent search string, allowing applications to share the search query—searching for text in Safari, then switching to Pages and finding the same text already in the search field because both apps read the find pasteboard. The font pasteboard stores font information for Copy Font/Paste Font operations in text editors. The ruler pasteboard stores paragraph formatting for Copy Ruler/Paste Ruler. These specialized pasteboards provide contextual data sharing beyond simple copy-paste.

NSPasteboardItem represents a single item on a pasteboard, providing multiple representations through data providers. When placing text and an image on a pasteboard as a single item, the application adds both representations to one NSPasteboardItem. Reading applications can inspect available types and request whichever they need. Multiple items on a pasteboard represent copying multiple separate objects (like multiple selected files), maintaining their identity as distinct objects rather than merging into one undifferentiated blob.

Promised data (NSPasteboardItemDataProvider) allows lazy data provision—an application declares it can provide specific UTI types without immediately generating the data. Only when a receiving application requests a specific type does the source application actually generate that representation. This is particularly valuable for large or complex data like high-resolution images that would be expensive to serialize unnecessarily.

Universal Clipboard (Handoff), introduced in macOS Sierra, extends the macOS clipboard across Apple devices. When Copy is performed on an iPhone, Mac, or iPad, the clipboard content becomes available on all other nearby Apple devices signed into the same iCloud account. This cross-device clipboard sharing requires Bluetooth LE for proximity detection and Wi-Fi for data transfer, working automatically when devices are nearby without explicit user action beyond performing the copy. The data is transferred encrypted and doesn’t persist beyond a short time window, balancing convenience with security.

Linux Clipboard Architecture

Linux clipboard architecture differs from Windows and macOS in several important ways, reflecting the X11 window system’s design philosophy and the more recent Wayland protocol’s different approach.

X11 implements a three-selection model rather than a single clipboard. The PRIMARY selection contains the current text selection—any text selected by highlighting it is automatically available in PRIMARY, and middle-clicking pastes PRIMARY contents without requiring explicit copy. This “select to copy, middle-click to paste” workflow predates Ctrl+C/Ctrl+V and remains deeply embedded in Unix culture, particularly among terminal and power users. The CLIPBOARD selection corresponds to what other operating systems call the clipboard—explicitly copied with Ctrl+C and pasted with Ctrl+V. The SECONDARY selection was intended as an auxiliary clipboard but is rarely used by modern applications.

This dual-selection model means Linux/X11 effectively maintains two separate clipboards simultaneously: PRIMARY (implicit, selection-based) and CLIPBOARD (explicit, command-based). Text editors, terminals, and many applications support both, allowing workflows impossible on other operating systems. A user can select text in one application (PRIMARY), then copy different text with Ctrl+C (CLIPBOARD), and paste either with middle-click (PRIMARY) or Ctrl+V (CLIPBOARD) respectively.

X11 clipboard ownership and lazy evaluation follow a specific protocol. When an application claims a selection (by responding to selection events), it becomes the owner. Other applications request specific data types through the TARGETS property (which types the owner can provide) and then request specific types. This request-response protocol is more complex than Windows’ shared memory approach but enables the lazy evaluation pattern naturally—data is only transferred when requested.

X11 clipboard loss occurs when a clipboard-owning application closes—unlike Windows where the clipboard data is stored by the OS independently of the owning application. When a terminal window containing selected text closes, the PRIMARY selection evaporates. Clipboard managers solve this by intercepting clipboard ownership events and storing data independently, so content persists after the source application closes.

Wayland’s clipboard design corrects X11’s limitations. Wayland’s security model means applications can’t access clipboard contents unless they’re the focused application, preventing clipboard snooping by background applications. Wayland handles both PRIMARY and CLIPBOARD selections but with tighter access control. Clipboard data persists across application closures when clipboard managers are present and integrated with the compositor.

KDE Klipper and GNOME’s clipboard integration provide clipboard history on Linux. Klipper is a standalone clipboard manager that integrates with KDE Plasma, maintaining clipboard history, allowing actions on clipboard contents (automatically opening URLs, transforming text), and providing a history popup. GNOME doesn’t include a built-in clipboard manager but supports third-party options like GPaste, Parcellite, or CopyQ, accessible through the top bar or keyboard shortcuts.

CopyQ is a cross-platform clipboard manager for Linux (also available on Windows and macOS) providing clipboard history, item tagging, scripting, and a comprehensive interface for managing clipboard contents. It integrates with both X11 and Wayland and provides sophisticated features like synchronized clipboard/selection, custom actions triggered on clipboard changes, and item editing.

Multi-Format Clipboard Data in Practice

Understanding how clipboard formats work in practice clarifies why pasting behaves differently in different contexts.

Text format negotiation determines what formatting is preserved when pasting. When copying formatted text from Word, the clipboard contains the text in multiple formats: native Word format (preserving everything), RTF (preserving most formatting), HTML (web-compatible formatting), and plain text (no formatting). Pasting into another Word document uses the Word format, preserving all formatting. Pasting into an email client likely uses HTML, preserving bold, italic, and headings. Pasting into a plain text editor requests the plain text format, stripping all formatting. The “Paste Special” or “Paste without formatting” option explicitly requests plain text format, useful when you want content without source formatting.

Image clipboard handling stores images in formats applications can use. Copying an image from a web browser typically places it on the clipboard as a bitmap (CF_BITMAP on Windows, public.image on macOS) and possibly as HTML containing an img tag referencing the original URL. An image editor receiving the paste would prefer the bitmap. A word processor might accept either bitmap or the HTML reference. File copying places file paths on the clipboard (CF_HDROP on Windows, public.file-url on macOS) along with potentially file contents in appropriate formats.

Clipboard and drag-and-drop share infrastructure in modern operating systems. The same multi-format data exchange mechanism that clipboard uses also underlies drag-and-drop operations. On macOS, NSPasteboard is used for both. On Windows, the IDataObject interface is shared between clipboard and OLE drag-and-drop. This sharing isn’t coincidental—clipboard and drag-and-drop both solve the same problem of transferring heterogeneous data between applications, and using shared infrastructure prevents duplication and ensures consistent behavior.

Format conversion by the OS transparently converts between certain related formats. Windows automatically converts between CF_TEXT and CF_UNICODETEXT (handling character encoding differences), and between CF_BITMAP and CF_DIB (device-independent bitmap formats). Applications placing text in CF_UNICODETEXT don’t need to also place it in CF_TEXT—Windows provides CF_TEXT automatically by converting from Unicode. Similarly, macOS UTI type hierarchies allow requesting a parent type and automatically receiving data that conforms to it.

Large data on clipboard presents memory challenges. Copying a high-resolution image or a large document places potentially hundreds of megabytes in the clipboard buffer. On Windows, clipboard data is stored in shared memory regions, with size limits loosely enforced. On macOS, pasteboard data is handled by the pboard daemon process. Applications should be mindful about what they place on the clipboard—unnecessarily copying the full data of very large objects wastes memory and slows pasting.

Clipboard Security and Privacy

The clipboard’s role as a shared data exchange buffer creates security and privacy considerations that operating systems and applications must carefully manage.

Clipboard snooping exploits the shared nature of clipboard data. On X11 Linux, any application can read the PRIMARY or CLIPBOARD selections at any time, allowing background applications to monitor everything copied by the user. This is how clipboard managers work but also how malicious software can capture sensitive data—passwords copied from password managers, financial information copied from banking sites, or confidential documents copied between applications. macOS and Wayland both address this by restricting clipboard access to focused applications only.

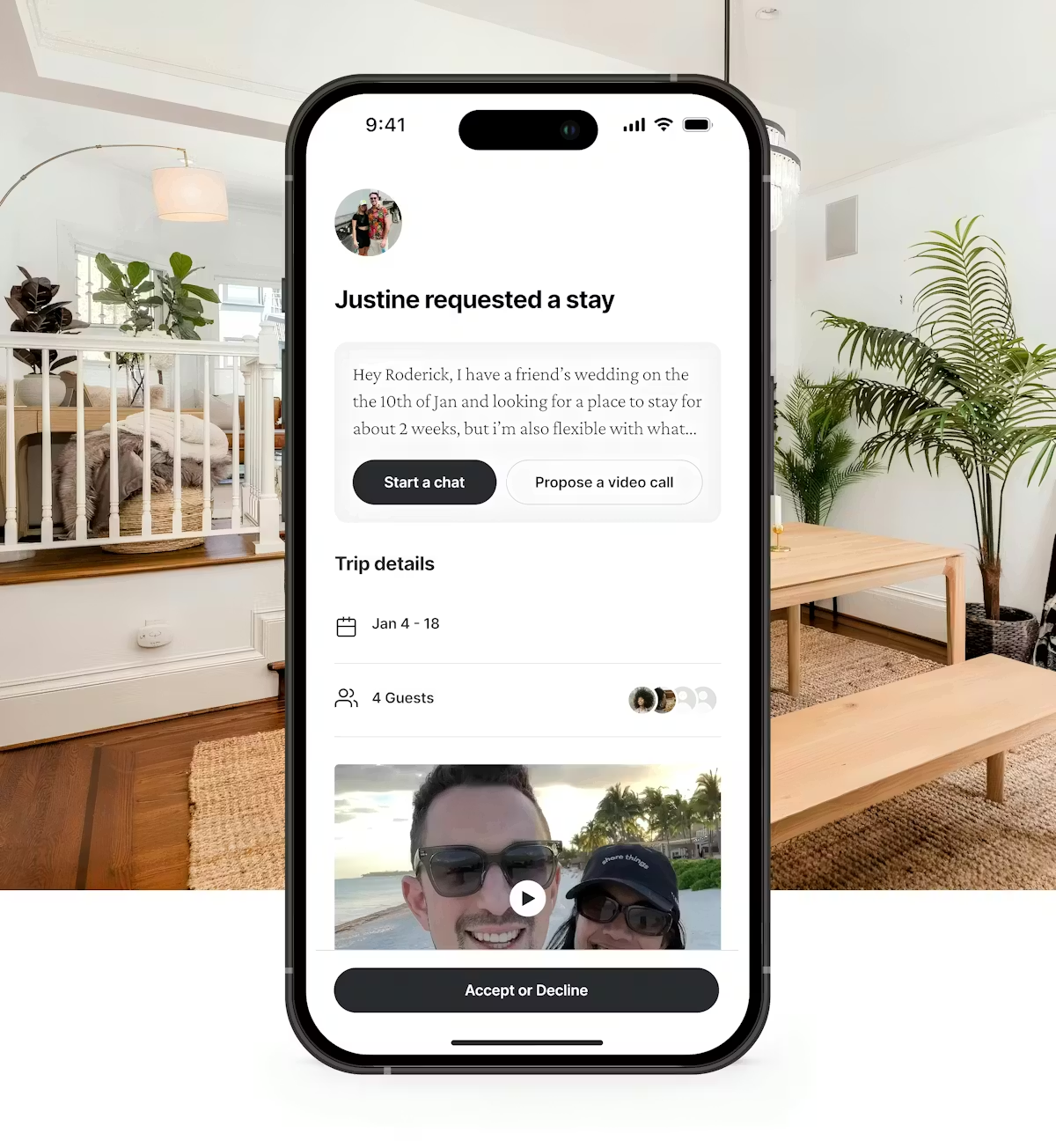

iOS and Android clipboard access restrictions reflect mobile operating systems’ stricter security models. iOS 14 and later shows a notification banner when apps access clipboard contents, alerting users to background clipboard reading. Android 10 and later prevents background apps from reading clipboard contents at all. These restrictions were implemented after researchers discovered many apps were unnecessarily reading clipboard contents, including sensitive data like passwords and personal information.

Clipboard warnings in iOS specifically identify which application read the clipboard, embarrassing some application developers whose apps were reading clipboard contents unnecessarily. After this transparency was added, many applications updated to stop reading clipboard data when not actively needed.

Sensitive data in clipboard history creates particular privacy concerns. When clipboard history features store hundreds of items over extended periods, they necessarily capture passwords, authentication tokens, personal information, and other sensitive content that was temporarily copied. Windows Clipboard History excludes certain sensitive content categories and allows syncing to be disabled. Users should periodically clear clipboard history (Win+V then “Clear all” on Windows, or through clipboard manager settings on other systems) to remove accumulated sensitive data.

Password manager clipboard handling must balance convenience against security. Copying passwords places them in the clipboard where they persist until cleared. Many password managers automatically clear the clipboard after a configurable timeout (typically 30-60 seconds) after copying a password, minimizing the window during which the password is clipboard-accessible. Some password managers use auto-type features that type passwords directly without using the clipboard, avoiding clipboard exposure entirely.

Clipboard exfiltration is a malware technique where malicious software monitors clipboard contents and replaces cryptocurrency addresses (or other valuable data) with attacker-controlled values before pasting. A user copying a Bitcoin address to send funds pastes a different address belonging to the attacker. Security software and vigilant users verify pasted values match copied originals for sensitive operations.

Secure input fields in some applications and operating systems prevent clipboard paste for security-sensitive entry. Some banking websites disable clipboard paste in password fields, though this practice is widely criticized as reducing security (by forcing users to type passwords, discouraging strong passwords) without providing meaningful protection. Most security experts recommend allowing clipboard paste in password fields.

Clipboard History Features Comparison

Clipboard history dramatically enhances clipboard utility by maintaining records of recent copies, enabling retrieval of content that would otherwise be lost when new content is copied.

Windows Clipboard History (Win+V) provides built-in history since Windows 10 1809. The history panel shows recent text and image items as tiles, supporting pin, delete, and clear operations. History syncs across Windows devices via Microsoft account when enabled. The 25-item limit is relatively modest, and history is lost when the OS restarts unless items are pinned. Text items show full content or truncation, image items show thumbnails.

macOS lacks built-in clipboard history—the OS provides only a single-item clipboard. Third-party applications fill this gap: Paste (commercial, iCloud sync between Apple devices), Alfred (productivity app with clipboard history as a feature), CopyClip (free, basic history in menu bar), and Clipboard Manager among others. The most capable solutions integrate with macOS Spotlight-like interfaces for searching clipboard history and provide syncing across Apple devices.

Linux clipboard managers like CopyQ, Klipper (KDE), GPaste (GNOME), and Parcellite provide history with varying sophistication. CopyQ offers the most features: unlimited history, item categories and tags, full search, scripting with Python/JavaScript, and custom actions. Klipper integrates deeply with KDE Plasma, providing history, configurable actions triggered on matching patterns (opening URLs when URL is copied), and cross-session persistence. These tools address X11’s clipboard loss problem alongside providing history.

Mobile clipboard history is available on Android through third-party keyboard apps. Gboard (Google’s keyboard) includes a built-in clipboard with history that persists for one hour by default. Samsung’s One UI includes a Samsung Keyboard clipboard feature. iOS doesn’t provide clipboard history beyond the most recent item, reflecting Apple’s stricter privacy stance.

Cross-platform clipboard synchronization services enable copying on one device and pasting on another platform. KDE Connect synchronizes clipboard between Android and Linux KDE. Microsoft Phone Link (formerly Your Phone) provides clipboard sync between Android and Windows. Various third-party tools like Clipt or PushBullet provide clipboard sync across platforms. These services are distinct from OS-level clipboard history but complement it for multi-device workflows.

Clipboard in Special Contexts

Clipboard behavior in specific contexts like remote desktop, virtual machines, and web browsers has unique characteristics and limitations.

Remote desktop clipboard sharing allows copying on a local machine and pasting in a remote session, or vice versa. RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) supports clipboard redirection where clipboard contents are automatically synchronized between local and remote sessions. When enabled, copying text in the remote desktop session makes it available for pasting locally and vice versa. This functionality enables working with remote systems nearly as seamlessly as local ones. Other remote access protocols (VNC, SSH with X11 forwarding) have varying levels of clipboard support.

Virtual machine clipboard integration allows data exchange between host and guest operating systems. VMware Tools and VirtualBox Guest Additions provide clipboard sharing between host and guest, typically requiring explicit enabling in VM settings. Without guest additions, clipboard is not shared, making data transfer between host and VM cumbersome. Bidirectional sharing lets users copy in the host and paste in the VM and vice versa, making development and testing workflows much smoother.

Web browser clipboard access through JavaScript is tightly controlled. The modern Clipboard API (navigator.clipboard) requires explicit user permission and only works in secure contexts (HTTPS). Websites can programmatically read clipboard contents only after the user grants clipboard read permission, addressing privacy concerns about websites secretly reading clipboard data. Writing to the clipboard (for “Copy to clipboard” buttons) is more permissive and allowed with user interaction without requiring explicit permission on most browsers.

Container and sandboxed application clipboard access may be restricted. Containerized applications (Flatpak on Linux, sandboxed Mac App Store apps) may have limited clipboard access depending on sandbox permissions. Applications must declare clipboard permissions to access clipboard in sandboxed environments, and clipboard contents may be subject to isolation depending on sandbox configuration.

Terminal clipboard handling requires specific key combinations because terminals use Ctrl+C as interrupt signal rather than copy. Most terminal emulators use Ctrl+Shift+C and Ctrl+Shift+V for clipboard operations, or use right-click context menus. On macOS, terminals maintain standard Cmd+C/Cmd+V. X11 terminal emulators typically support both PRIMARY (select to copy, middle-click to paste) and CLIPBOARD (Ctrl+Shift+C/V) conventions.

Clipboard APIs for Developers

Application developers interact with clipboard systems through platform-specific APIs, and understanding these APIs reveals how clipboard functionality works at a technical level.

Windows clipboard API usage follows a pattern: call OpenClipboard(hwnd) to acquire clipboard access, EmptyClipboard() to clear existing contents when setting new data, SetClipboardData(format, handle) for each format being provided, and CloseClipboard() to release access. Reading uses OpenClipboard(), GetClipboardData(format) to get data handles, and CloseClipboard(). Proper resource management—always closing the clipboard even on errors, not holding it open longer than necessary—prevents other applications from accessing the clipboard.

macOS NSPasteboard API centers on declarative type specification. NSPasteboard.general.clearContents() clears current contents. NSPasteboard.general.setString(:forType:) or writeObjects(🙂 with objects conforming to NSPasteboardWriting places data. Reading uses string(forType:) or readObjects(forClasses:options:) with desired types. The UTI-based type system and NSPasteboardWriting/NSPasteboardReading protocols provide clean abstractions for both system-defined types and custom application types.

Linux clipboard access through Xlib requires working with X11 selection protocols directly, which is complex—applications must handle SelectionRequest events, respond with the requested data format, and manage selection ownership. Most Linux developers use higher-level toolkits: GTK provides gtk_clipboard_get() and convenience functions for text and images, Qt provides QClipboard with similar simplicity. These toolkit abstractions hide the X11 selection protocol complexity.

Cross-platform clipboard libraries enable applications targeting multiple platforms to use a single clipboard API. Qt’s QClipboard works consistently across Windows, macOS, and Linux. Electron applications use electron’s clipboard module. Flutter’s Clipboard class provides cross-platform clipboard access. These abstractions handle platform differences transparently, though they sometimes expose lowest-common-denominator functionality rather than platform-specific extensions.

Conclusion

The clipboard is one of the most fundamental interoperability mechanisms in modern computing—a deceptively simple “copy and paste” capability that underpins countless productivity workflows while requiring sophisticated operating system infrastructure to work reliably across diverse applications, data types, and user scenarios. From Windows’ shared memory model and built-in history, to macOS’s pasteboard architecture with named specialized pasteboards, to Linux’s unique dual-selection model from X11 tradition, each operating system has developed distinctive clipboard implementations reflecting different design philosophies and historical development paths.

Understanding clipboard functionality clarifies why pasting behavior differs in different applications (format negotiation in action), why clipboard contents sometimes disappear unexpectedly (application closure in X11, history limits), why clipboard history features require specific enablement, and how security vulnerabilities exploiting clipboard access work. For users, this knowledge enables more productive use of clipboard features—knowing about clipboard history, format-specific pasting, cross-device synchronization, and the privacy implications of what gets copied. For developers, clipboard API knowledge is essential for building applications that exchange data smoothly with other applications in the ecosystem, respecting platform conventions while providing great user experiences.

As computing increasingly spans multiple devices and platforms, clipboard functionality evolves from a single-machine buffer to a cross-device synchronization service—Universal Clipboard across Apple devices, Windows Clipboard History syncing across PCs, and third-party solutions bridging different platforms. The fundamental concept remains unchanged: a temporary shared space where copied data waits patiently for its destination, enabling the fluid movement of information between applications that makes modern computing productivity possible.

Summary Table: Clipboard Architecture Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | macOS | Linux (X11) | Linux (Wayland) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clipboard Model | Single clipboard (CLIPBOARD) | Multiple pasteboards (general, find, font, ruler) | Two selections: PRIMARY + CLIPBOARD | CLIPBOARD + PRIMARY (compositor-managed) |

| Primary Copy Shortcut | Ctrl+C | Cmd+C | Ctrl+C (CLIPBOARD) | Ctrl+C (CLIPBOARD) |

| Primary Paste Shortcut | Ctrl+V | Cmd+V | Ctrl+V (CLIPBOARD) | Ctrl+V (CLIPBOARD) |

| Secondary Paste | None | None | Middle-click (PRIMARY) | Middle-click (PRIMARY, limited) |

| Select-to-Copy | No | No | Yes (PRIMARY selection) | Compositor-dependent |

| Data Persistence | Persists after source app closes | Persists after source app closes | Lost when source app closes | Compositor-managed persistence |

| Format System | CF_ constants + custom format names | UTI (Uniform Type Identifiers) | MIME types + X11 atoms | MIME types + Wayland protocols |

| Clipboard History | Built-in (Win+V, 25 items, since Win 10 1809) | Third-party only (Paste, Alfred, CopyClip) | Third-party (CopyQ, Klipper, GPaste) | Third-party (CopyQ with Wayland support) |

| Cross-Device Sync | Windows Clipboard History (Microsoft account) | Universal Clipboard (iCloud, nearby Apple devices) | KDE Connect (Android-Linux), third-party | KDE Connect (Plasma + Wayland) |

| Background App Access | Allowed (listener API) | Restricted to focused app (modern macOS) | Allowed (any X11 app can read) | Restricted to focused app |

| Privacy Notifications | None | None (unlike iOS) | None | None |

| Secure Input Clipboard | Application-controlled | Application-controlled | Application-controlled | Application-controlled |

| Primary API | Win32: OpenClipboard, GetClipboardData, SetClipboardData | NSPasteboard (Cocoa), UIPasteboard (UIKit) | X11 Xlib selections, GTK/Qt abstractions | wl-clipboard, GTK/Qt Wayland backends |

| Cut Shortcut | Ctrl+X | Cmd+X | Ctrl+X | Ctrl+X |

| Clear Clipboard | Win+V then Clear all | pbcopy < /dev/null (terminal) | xclip -i /dev/null or xdotool | wl-copy < /dev/null |

Clipboard Data Formats and Compatibility:

| Data Type | Windows Format | macOS UTI | Linux MIME Type | Pasting Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain text | CF_UNICODETEXT / CF_TEXT | public.plain-text | text/plain | Universal paste — always available |

| Rich text (RTF) | CF_RTF (custom registered) | public.rtf | text/rtf | Pastes with formatting in RTF-aware apps |

| HTML | CF_HTML (custom registered) | public.html | text/html | Preserves web formatting in supporting apps |

| Bitmap image | CF_BITMAP / CF_DIB | public.tiff / public.image | image/png, image/bmp | Pastes as embedded image |

| File paths | CF_HDROP | public.file-url | text/uri-list | Pastes as file reference or triggers file operation |

| Word document | Custom (Word format) | com.microsoft.word.doc | application/msword | Only pastes in Word or compatible apps |

| Custom | com.adobe.pdf | application/pdf | Pastes in PDF-aware apps | |

| URL | CF_TEXT (plain URL) | public.url | text/uri-list | Pastes as text or live link depending on app |

| Formatted spreadsheet | Custom (Excel format) | com.microsoft.excel.xls | application/vnd.ms-excel | Only pastes as table in compatible apps |