Every day, you make decisions about what to do with your computer when you’re done using it. Should you shut it down completely? Put it to sleep? Use hibernation? These choices might seem simple on the surface, but they represent fundamentally different approaches to power management, each with distinct technical implementations, advantages, and appropriate use cases. Understanding these differences can help you make better decisions, save energy, extend your hardware’s lifespan, and match your computer’s behavior to your actual needs.

When you close your laptop lid or walk away from your desktop, your computer doesn’t just have two states: on or off. Modern operating systems implement a sophisticated spectrum of power states, each representing a different balance between power consumption, resume speed, and system preservation. These power states exist because computers face a fundamental tension. Users want their computers to be instantly available when needed, which suggests keeping everything powered and ready. But computers consume significant electricity, generate heat, and wear out hardware through continuous operation, which suggests powering down when not in use.

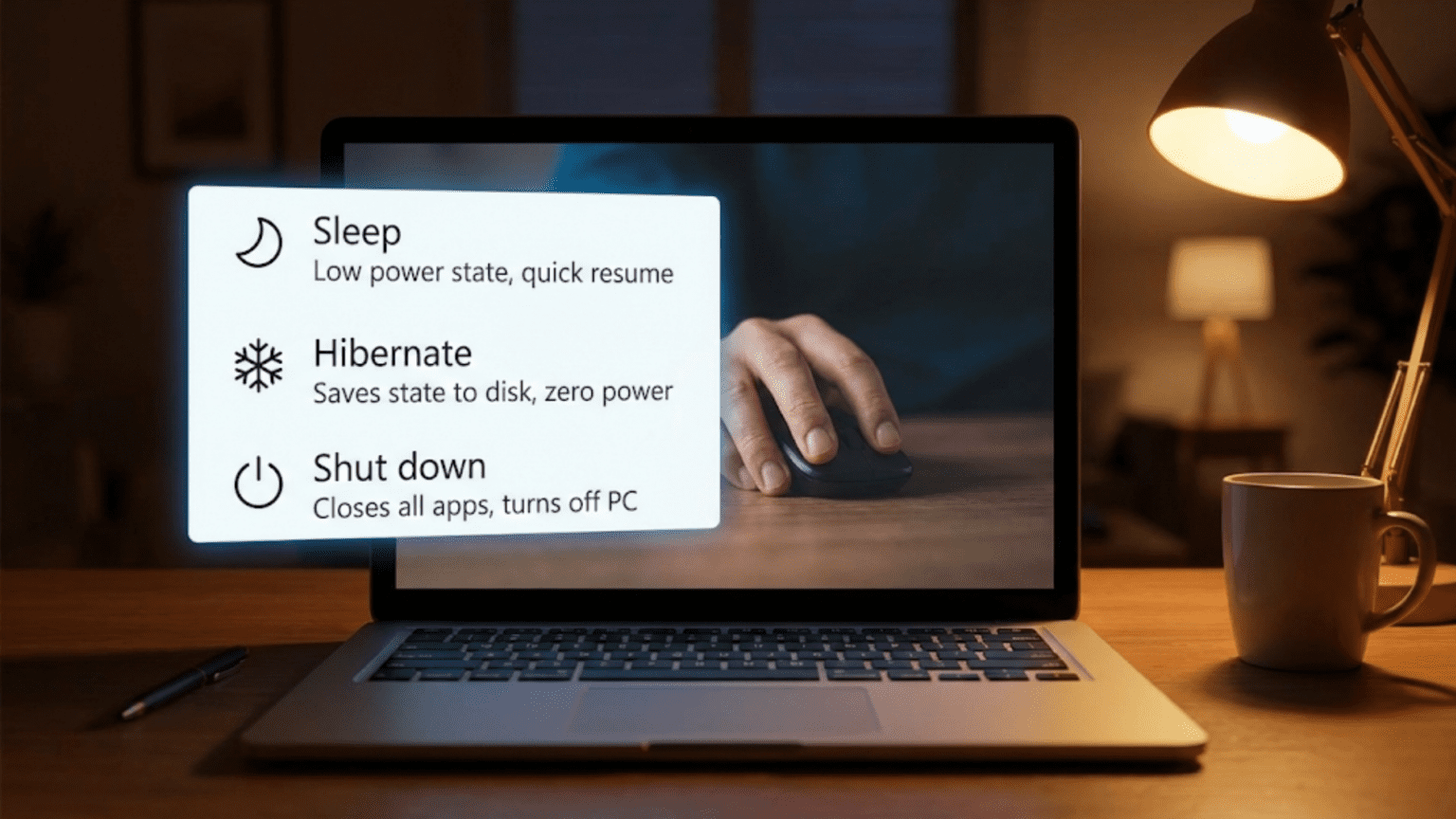

The three most common power states that users interact with are shutdown, sleep, and hibernation, though the technical reality includes many more intermediate states. Each represents a different solution to the power-versus-readiness tradeoff. Shutdown turns nearly everything off, consuming minimal power but requiring a full boot process to become usable again. Sleep keeps just enough powered to resume quickly while dramatically reducing power consumption. Hibernation achieves nearly shutdown-level power savings while still allowing relatively quick resume by using a clever trick involving your storage device.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll examine each of these power states in detail, understanding exactly what happens when you invoke them, how the operating system implements them, what’s still running and what’s turned off, and when each state is most appropriate. We’ll look at the technical mechanisms that make these states possible, the evolution of power management in operating systems, and the practical considerations that should guide your choices. By the end, you’ll have a thorough understanding of these fundamental operating system capabilities and be able to use them effectively.

What Actually Happens During Shutdown

When you tell your computer to shut down, you’re initiating one of the most orderly and complex processes the operating system performs. Shutdown isn’t simply cutting power; it’s a carefully choreographed sequence that ensures your data is safe, your hardware is in a proper state, and everything is prepared for the next boot.

The shutdown process begins when you issue the shutdown command through your operating system’s interface. The operating system’s power management subsystem takes control and starts coordinating the shutdown sequence. The first step typically involves notifying all running applications that the system is about to shut down. This gives applications the opportunity to save their state, prompt users to save unsaved work, and close files properly.

You’ve probably experienced this when an application asks if you want to save your work before the system shuts down. This is the application responding to the shutdown notification from the operating system. Well-behaved applications will save their state and exit cleanly. If an application doesn’t respond or refuses to close, the operating system must decide whether to wait, force the application to close, or ask the user what to do. This is why shutdown sometimes takes longer than expected, particularly when applications have unsaved data or are misbehaving.

Once applications have closed, or been forcibly terminated if necessary, the operating system begins shutting down its own services and subsystems. Background services that have been running must be stopped in an orderly fashion. Databases must flush their buffers and close cleanly. Network connections must be terminated properly. Log files must be closed. Each subsystem has its own shutdown procedure, and the operating system coordinates these in the proper order, ensuring that dependencies are respected.

A critical part of the shutdown process involves ensuring all data in memory is written to permanent storage. Modern operating systems use extensive caching, keeping frequently accessed file data in RAM for quick access. During normal operation, changes you make to files might initially only modify the cached version in RAM, with the actual write to disk happening later for efficiency. But during shutdown, all these pending writes must be completed. The operating system flushes all filesystem caches, ensuring that every change is safely written to disk. This is why you should never simply turn off power without properly shutting down; doing so risks losing data that exists only in these caches.

The operating system also updates various system state files during shutdown. It might record that the system was shut down cleanly, which helps it know during the next boot whether to check filesystems for corruption. It updates configuration files that track system state. It records the time of shutdown and other metadata that might be useful for system administration or diagnostics.

Once the software side of shutdown is complete, the operating system communicates with the hardware to actually power down. On modern systems, this involves sending commands through the ACPI (Advanced Configuration and Power Interface) system, which is a standardized way for operating systems to control power management hardware. The operating system tells the ACPI system to transition to the G2/S5 state, which is the official designation for “soft off.”

In this state, nearly everything is powered down. The CPU stops executing instructions. RAM loses power and all its contents disappear. Most expansion cards and devices power down. The display turns off. However, a tiny amount of power remains available to certain components. The network interface might remain powered in a low-power state so it can wake the computer if it receives a special network packet, a feature called Wake-on-LAN. USB ports might receive minimal power if configured to allow devices to wake the computer. The power supply remains in standby mode, ready to fully power up when you press the power button.

This residual power is why many computers have an LED that remains lit even when shut down, and why some draw a small amount of power from the wall even when “off.” The actual power consumption in shutdown state is typically very small, perhaps a few watts at most, though completely disconnecting power eliminates even this.

Understanding shutdown helps clarify what it isn’t. It’s not just stopping the current work; it’s a complete, orderly cessation of all computing activity, with careful preservation of state and preparation for the next boot. The next time you power on, the system starts fresh, loading the operating system from scratch, initializing all hardware, and starting all services anew.

Sleep: The Quick Pause

Sleep mode, sometimes called standby or suspend, represents a fundamentally different approach to power management. Rather than shutting everything down, sleep preserves the current state of your system in RAM while powering down most other components. This allows the computer to resume almost instantly, picking up exactly where you left off, while still achieving dramatic power savings compared to running normally.

When you put your computer to sleep, the operating system’s power management system coordinates a different kind of transition. Applications aren’t closed; instead, they’re essentially frozen in their current state. The operating system pauses all running programs, suspends all processes, and prepares the system for the sleep state. This happens so quickly that you typically don’t notice any delay between initiating sleep and the computer appearing to be off.

The key insight behind sleep mode is that RAM, which holds all your current work, your open applications, and the operating system itself, can remain powered with very little energy. RAM is volatile memory, meaning it loses its contents when power is removed, but it only needs a tiny trickle of power to maintain its stored data. By keeping RAM powered while shutting down almost everything else, sleep mode preserves your entire working state while consuming minimal power.

The CPU stops executing instructions and enters a deep power-saving state. The display turns off. Hard drives or SSDs stop spinning or become inactive. The graphics card powers down to a minimal state. Cooling fans stop or slow dramatically since there’s little heat being generated. Network interfaces might remain in a low-power monitoring mode if wake-on-LAN is enabled. USB devices might power down depending on configuration. Essentially, anything that consumes significant power and isn’t needed to maintain RAM stops running.

The power consumption in sleep mode varies depending on the specific computer and configuration, but it’s typically very low. A laptop might consume just a few watts in sleep mode, allowing the battery to last for days or even weeks while sleeping. A desktop might consume a bit more but still far less than the hundreds of watts it might use during active operation. This dramatic reduction in power consumption is what makes sleep mode practical for extended periods.

The beauty of sleep mode is in the resume process. Because your entire system state remains in RAM, waking from sleep simply involves powering the hardware back up and allowing the CPU to resume executing where it left off. The operating system doesn’t need to reload from disk. Applications don’t need to restart. You don’t need to reopen your documents or browser tabs. Everything is exactly as you left it. This process typically takes just a few seconds, sometimes even less, making sleep ideal for short breaks or moving between locations.

However, sleep mode has important limitations. Because it depends on maintaining power to RAM, a loss of power means a loss of all your work. If a laptop’s battery drains completely while in sleep mode, or if a desktop loses power due to an outage or the plug being disconnected, the contents of RAM disappear and you lose everything that wasn’t saved to disk. This is why operating systems often implement a hybrid sleep mode that combines aspects of sleep and hibernation, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Sleep mode also continues to drain battery, albeit slowly. While a laptop might last days in sleep mode, it will eventually run out of power if not plugged in. For extended periods of not using the computer, hibernation or shutdown might be more appropriate.

Different operating systems and hardware implementations use slightly different terminology and may support multiple variants of sleep. Modern systems often implement what’s called S3 sleep, where RAM remains powered but nearly everything else shuts down. Some newer systems support a “modern standby” or “connected standby” mode that keeps slightly more components powered to allow background tasks to continue at a very low level. The specific behavior can vary, but the fundamental concept remains the same: preserve state in RAM while minimizing power consumption elsewhere.

Hibernation: The Best of Both Worlds

Hibernation represents an elegant solution to a problem that both shutdown and sleep leave partially unsolved. Shutdown saves maximum power but loses your working state and requires slow boot times. Sleep preserves your state and resumes quickly but requires continuous power and risks data loss if power is interrupted. Hibernation achieves the power savings of shutdown while preserving state and allowing relatively quick resume through a clever use of your storage device.

When you initiate hibernation, the operating system performs a sophisticated operation. It takes the entire contents of RAM, which represents your complete system state including the operating system, all running applications, all open documents, and everything else currently in memory, and writes it to a special file on your hard drive or SSD. This file is often called the hibernation file, swap file, or sometimes the page file, depending on the operating system and whether it’s used for other purposes as well.

Writing gigabytes of data from RAM to disk takes some time, which is why entering hibernation is noticeably slower than entering sleep. On a modern system with an SSD, it might take fifteen to thirty seconds. On an older system with a traditional hard drive, it could take considerably longer. The speed depends on how much RAM you have, how fast your storage device is, and how efficiently the operating system can perform the transfer.

Once the contents of RAM have been safely written to disk, the operating system can shut down completely. It powers off RAM, knowing that the data is preserved on disk. It shuts down all other components just like a normal shutdown. The system enters the same G2/S5 “soft off” state as a full shutdown, consuming minimal power, just enough to detect when the power button is pressed.

The magic happens during resume from hibernation. When you power on the computer, the BIOS or UEFI firmware recognizes that a hibernation file exists and hands control to the operating system’s hibernation resume code. Instead of performing a normal boot process, loading the operating system fresh from scratch, the system reads the hibernation file from disk and loads its contents back into RAM. This restores the exact state that existed when hibernation began.

Once RAM is restored, the CPU can resume execution at the point where it stopped when entering hibernation. The operating system doesn’t need to initialize itself fully; it’s already initialized, just loaded from disk rather than going through the normal boot process. Applications don’t need to start; they’re already running, their state restored from the hibernation file. Your documents, browser tabs, and everything else reappears exactly as you left them.

This resume process is faster than a cold boot but slower than waking from sleep. On modern hardware with fast SSDs, resuming from hibernation might take thirty seconds to a minute. This is considerably faster than the full boot process, which might take several minutes on the same system, but noticeably slower than the few seconds required to wake from sleep.

Hibernation’s key advantage is that it combines the power savings of shutdown with the state preservation of sleep. Your computer uses essentially no more power than if shut down completely, yet your work is preserved and can be resumed without starting fresh. This makes hibernation ideal for situations where you’ll be away from your computer for an extended period but want to resume your work when you return.

The hibernation file consumes disk space equal to the amount of RAM in your system. If you have sixteen gigabytes of RAM, the hibernation file will be about sixteen gigabytes. On modern systems with large storage devices, this is rarely a concern, but on older systems with limited disk space, it could be significant. Some operating systems allow you to disable hibernation to reclaim this disk space if you don’t use the feature.

Different operating systems implement hibernation slightly differently. Windows has historically provided hibernation as a distinct option separate from sleep. macOS integrates it more subtly; when you close a MacBook, it enters sleep, but if the battery runs low, the system automatically hibernates to prevent data loss. Linux systems support hibernation but configuration varies by distribution. Understanding these differences helps you use each system effectively.

Hybrid Sleep: Combining Strategies

Many modern systems implement a mode called hybrid sleep that attempts to capture the best aspects of both sleep and hibernation while minimizing their drawbacks. Understanding hybrid sleep helps clarify how operating systems continue to evolve their power management strategies to better serve users.

Hybrid sleep works by simultaneously entering both sleep and hibernation. When you put the computer into hybrid sleep, it writes the contents of RAM to the hibernation file on disk, just like hibernation. But unlike pure hibernation, it then keeps RAM powered and enters the sleep state rather than shutting down completely. This gives you the quick resume of sleep mode while providing the safety net of hibernation.

The advantage becomes clear if you consider what happens in different scenarios. If power remains available, the computer can resume from RAM just like normal sleep, giving you the fast, instant-on experience. But if power is lost, whether because a laptop battery drains or a desktop loses wall power, the hibernation file on disk preserves your state. When power returns, the system can resume from the hibernation file, recovering your work rather than losing everything.

Hybrid sleep is particularly useful for desktop computers, which might experience unexpected power outages. It’s also valuable for laptops when you’re not sure how long they’ll be in sleep mode. If you close your laptop for a brief meeting, you get fast resume. If you leave it closed over a weekend and the battery drains, you still have your work when you return.

The tradeoff is that entering hybrid sleep takes longer than pure sleep because the hibernation file must be written, and it consumes slightly more disk I/O. For systems with SSDs where disk writes have a theoretical lifetime limit, this might be a consideration, though modern SSDs are durable enough that this is rarely a practical concern.

Some operating systems use hybrid sleep as the default sleep mode, while others provide it as an option that can be enabled. Windows often uses hybrid sleep on desktops by default while using standard sleep on laptops. Understanding what your system is doing helps you make informed configuration choices.

Fast Startup: Hibernation for the Operating System

A related concept that’s become common in modern operating systems is fast startup, sometimes called hybrid boot or fast boot. This feature uses hibernation techniques to speed up the boot process, blurring the line between shutdown and hibernation.

With fast startup enabled, when you shut down your computer, the operating system doesn’t perform a complete shutdown in the traditional sense. Instead, it closes all user applications and logs out all users, but rather than shutting down the kernel and all system services, it hibernates them. The kernel and core system services are written to the hibernation file just like during full hibernation, but user session data is not preserved.

When you next boot the computer, instead of initializing the operating system completely from scratch, the system loads the hibernated kernel and services from the hibernation file. This skips much of the initialization work that normally happens during boot, resulting in significantly faster startup times. The improvement can be dramatic, reducing boot times from minutes to seconds on some systems.

However, fast startup is distinct from full hibernation in important ways. Your applications aren’t preserved; when the system starts, you’re at a fresh login screen with no applications running. Any unsaved work is lost just as with a normal shutdown. The feature only accelerates the operating system’s initialization, not application startup.

Fast startup can sometimes cause issues with dual-boot systems or with certain hardware that expects a complete power cycle during shutdown. Some systems require periodic complete shutdowns to properly reset hardware or clear certain types of errors. Understanding whether your system uses fast startup helps explain its boot behavior and troubleshoot related issues.

Windows 10 and later versions enable fast startup by default, though it can be disabled. Other operating systems implement similar concepts under different names. The trend toward faster boot times has made these hybrid approaches increasingly common.

The Technical Foundation: ACPI and Power States

To fully understand sleep, hibernation, and shutdown, it helps to know about the technical standards that enable them. The Advanced Configuration and Power Interface, or ACPI, provides a standardized framework for operating systems to control power management across different hardware platforms.

ACPI defines a hierarchy of power states with specific designations. The global states, labeled G0 through G3, represent major system states. G0 is working, meaning the system is fully operational. G1 encompasses all the sleeping states. G2 is soft off, what we call shutdown. G3 is mechanical off, where the system is completely disconnected from power.

Within G1, ACPI defines several sleep states labeled S0 through S5, though not all are used in practice. The S0 state is actually working state, part of G0. S1 and S2 are shallow sleep states rarely used in modern systems where the CPU stops but other components remain powered. S3 is the sleep state we’ve been discussing, where RAM remains powered but most other components shut down. S4 is hibernation, where the system state is saved to disk before powering off. S5 is soft off, corresponding to shutdown.

Modern systems also support multiple CPU power states, labeled C0 through C6 or higher, representing different depths of CPU sleep. C0 is active operation. Deeper C-states progressively shut down more CPU functions, saving more power but requiring more time to wake. The operating system can put the CPU into these states during idle periods, even when the system overall is in the working state, saving power opportunistically.

Similarly, device power states, labeled D0 through D3, allow individual devices to enter low-power modes independently. A network card might be in D3 while the system is otherwise active if it’s not currently in use. USB devices can enter suspend states. Hard drives can spin down. These granular power states allow sophisticated power management that adapts to actual usage patterns.

The operating system power manager coordinates all these states, deciding when to transition components to lower power states based on activity, managing the wake-up process when devices are needed again, and ensuring system stability throughout. This is complex work, requiring the operating system to understand the capabilities and dependencies of all hardware components and to coordinate their power states coherently.

ACPI also defines mechanisms for waking the system from sleep states. Wake events can come from various sources: pressing the power button, opening a laptop lid, receiving a network packet if wake-on-LAN is enabled, pressing a key on the keyboard, moving the mouse, or a scheduled task triggering. The operating system configures which events should wake the system based on user preferences and system policy.

Understanding ACPI helps explain why power management behavior can vary across different computers even when running the same operating system. Hardware support for various ACPI states varies. Some laptops implement all sleep states robustly while others have compatibility issues. Some devices wake reliably from sleep while others occasionally get confused. These variations reflect differences in how manufacturers implement the ACPI specification.

Practical Considerations: When to Use Each State

With understanding of how sleep, hibernation, and shutdown work technically, we can consider when each is most appropriate. The right choice depends on your usage patterns, priorities, and specific situation.

Shutdown is appropriate when you’ll be away from your computer for an extended period, when you want to ensure absolutely minimal power consumption, when you’re troubleshooting problems and want a completely fresh start, or when you’re transporting the computer and want to be certain all components are fully powered down. Shutting down regularly, perhaps daily, gives hardware a chance to reset and can help clear certain types of transient problems. It’s the safest option before installing major system updates or hardware changes.

Sleep is ideal for short breaks, when you’re moving between locations but will use the computer again soon, or anytime you want instant resume but will be back within a few hours or perhaps a day. For laptops with good battery life, sleep mode can maintain state for multiple days, making it practical even for longer breaks. The instant-on experience of sleep mode has made it many users’ default choice for any pause in work.

Hibernation makes sense when you’ll be away for days or longer but want to preserve your working state, when you want to save battery on a laptop while not using it but maintain your session, or when you want the convenience of sleep but the power savings of shutdown. It’s particularly valuable if you work in long sessions with many applications and documents open that would be tedious to reopen. The slower resume time compared to sleep is a reasonable tradeoff for the power savings and state preservation over extended periods.

For many users, a hybrid approach works well. You might use sleep for overnight or weekend breaks, hibernation before trips or when you know you won’t use the computer for a week, and shutdown when performing maintenance or troubleshooting. Some people shutdown nightly out of habit or preference for starting fresh each day. Others might leave their computers in sleep mode continuously, only shutting down for updates or problems.

Battery health considerations affect these choices on laptops. Keeping a laptop constantly plugged in at 100 percent charge can reduce long-term battery health. Some users prefer to run their laptop on battery during the day, let it sleep overnight while charging, and occasionally let it discharge more completely. This usage pattern naturally involves more sleep cycles. Others prefer to shut down when not in use to minimize battery charge cycles.

Desktop systems have different considerations. Power consumption is paid rather than limited by battery, making the cost of leaving the system in sleep versus hibernating versus shutting down a factor. However, the environmental impact of energy consumption is worth considering. A desktop in sleep mode uses more power than one in hibernation or shutdown, which adds up over time if the system is idle for many hours daily.

Hardware reliability considerations sometimes influence these choices. Hard drives experience wear from spin-up cycles, potentially making continuous operation or sleep preferable to frequent full shutdowns. SSDs have no moving parts and don’t care about these cycles. Cooling fans experience wear from operation, potentially favoring shutdown or hibernation that turns them off. None of these factors is usually decisive in isolation, but they’re worth awareness.

System stability can also play a role. Some systems develop issues after running for very long periods without restart, such as memory leaks in drivers or applications gradually degrading performance. Regular restarts, whether through shutdown or the restart command that shuts down and immediately boots again, can prevent or resolve these issues. Other systems run perfectly for months without restart. Knowing your system’s behavior helps guide these decisions.

Power Management Configuration and Settings

Operating systems provide various settings to control power management behavior, and understanding these settings helps you configure your system to match your preferences and needs.

Most systems allow you to configure when automatic sleep occurs. You can typically set different timeouts for battery versus plugged-in operation on laptops. You might configure your laptop to sleep after ten minutes on battery but never sleep when plugged in. Or you might prefer automatic sleep after thirty minutes regardless of power source to save energy.

Display sleep is usually configured separately from system sleep. Your display might turn off after five minutes of inactivity, but the system might not sleep for thirty minutes. This saves the power consumed by the display while keeping the system active for background tasks. Some users prefer aggressive display sleep but no automatic system sleep, maintaining system availability while reducing power consumption.

Hibernation settings control whether the feature is enabled at all, how much disk space to allocate for the hibernation file, and whether hybrid sleep is used. Some systems hide hibernation options by default and require manual configuration to expose them. Understanding your system’s configuration interface helps you enable features you want and disable those you don’t.

Wake settings determine what events can wake the system from sleep. You can usually control whether keyboard input, mouse movement, network activity, or scheduled tasks can wake the system. Some users disable most wake sources to prevent accidental waking, while others enable many sources for maximum convenience.

Power plans or power profiles bundle multiple settings together for different scenarios. A power-saving plan might enable aggressive sleep, reduce display brightness, and throttle CPU performance. A high-performance plan might disable most automatic power management. A balanced plan attempts to compromise between performance and power savings. You can usually customize these plans or create your own.

Understanding that these settings exist and where to find them in your operating system’s interface empowers you to configure power management to suit your specific needs rather than accepting defaults that might not match your usage patterns.

The Evolution of Power Management

Power management in operating systems has evolved tremendously over the decades, and understanding this evolution provides perspective on current capabilities and future directions.

Early personal computers had essentially two states: on and off. When you turned off the computer, you cut power completely. When you turned it on, it booted from scratch. There was no sleep, no hibernation, no sophisticated power management. This simplicity had the advantage of being easy to understand but the disadvantage of wasting power and requiring slow boot times.

The introduction of software-controlled power management changed this. Operating systems gained the ability to power down specific components like monitors or hard drives while leaving the system otherwise running. You might configure your monitor to turn off after fifteen minutes, saving significant power in the days of power-hungry CRT displays, while the computer itself continued running.

Laptops drove major advances in power management because battery life is such a critical concern for portable computers. Early laptops implemented basic suspend modes, often in firmware rather than the operating system, that would pause the system and reduce power consumption. These early suspend implementations were often fragile, with many devices not handling suspend and resume properly.

The development of ACPI in the late 1990s standardized power management and gave operating systems much more control. This enabled the sophisticated sleep states we use today, with reliable suspend and resume across a wide variety of hardware. Operating systems could now coordinate complex power transitions involving many components.

Hibernation emerged as a feature that initially required third-party software on many systems but eventually became integrated into operating systems. The ability to save the entire system state to disk and resume from it represented a significant advance in making power management both safe and convenient.

Modern developments include more granular power management where individual components can enter low-power states independently rather than the entire system transitioning between a few discrete states. CPUs that can put individual cores to sleep while others remain active, displays with variable refresh rates that can reduce power consumption when showing static content, and SSDs that can enter power-saving modes between accesses all represent this trend toward finer-grained power management.

Connected standby or modern standby represents a newer approach where the system can perform certain activities like receiving notifications or syncing data while still being mostly asleep. This blurs the line between sleep and active states, creating something in between that can respond to certain stimuli while still maintaining low power consumption.

The future likely includes even more sophisticated power management that adapts to usage patterns using machine learning, more efficient hardware that makes the tradeoffs less stark, and better integration between operating systems and applications so that power management becomes more transparent while remaining effective.

Troubleshooting Power Management Issues

Power management, despite being generally reliable on modern systems, can sometimes malfunction, and understanding common issues helps you troubleshoot effectively.

Sleep problems are common complaints. A system might refuse to sleep, immediately waking after entering sleep, or failing to wake properly when you want it to. These issues can stem from various causes. A device driver might prevent sleep, either intentionally because the device is active or due to a bug. You can often check what’s preventing sleep using operating system utilities that report wake sources and sleep blockers.

Hibernate problems often relate to the hibernation file. If there isn’t enough disk space for the file, hibernation will fail. If the file becomes corrupted, resume from hibernation might fail, forcing a normal boot. Some systems have issues with hibernation after certain updates, sometimes requiring you to recreate the hibernation file.

Devices not waking properly from sleep is another common issue. Network cards, in particular, sometimes have problems. After waking from sleep, the network might not work until you disconnect and reconnect, or restart. This usually indicates a driver issue where the device isn’t properly implementing the resume process. Updating drivers often resolves these problems.

Wake-on-LAN and other wake features can cause mysterious waking behavior where the system wakes from sleep at unexpected times. A network packet, a scheduled task, or even a mouse vibration from bumping your desk might wake the system. Examining wake history and selectively disabling wake sources can identify the culprit.

Battery drain during sleep indicates that something isn’t entering a proper low-power state. Background tasks might prevent deep sleep, or a device might remain active unnecessarily. Power usage reports available in most operating systems can help identify what’s consuming power.

Some problems relate to BIOS or UEFI settings rather than the operating system. Certain power management features might need to be enabled in BIOS, or specific compatibility modes might interfere with sleep. Checking and updating BIOS can resolve some power management issues.

Understanding that power management involves complex coordination between operating system, drivers, and hardware helps you approach troubleshooting systematically. Problems often lie at the interfaces between these components, and resolving them might require updating different parts of the system.

Security Considerations in Power Management

Power management has security implications that aren’t always obvious but are worth understanding, particularly in sensitive environments.

When a system is in sleep mode, RAM remains powered and contains all the data that was there when sleep began. This includes any sensitive data that applications or the operating system had in memory, encryption keys, passwords, and potentially copies of documents. If someone gains physical access to a sleeping computer, particularly a laptop, they might theoretically extract this data from RAM using specialized techniques.

This is why some high-security environments mandate full shutdown or hibernation rather than sleep, and why encryption of the hibernation file is important. When the hibernation file is encrypted, as it is by default on systems with full-disk encryption enabled, the saved state is protected even if the storage device is physically removed.

Some systems implement memory scrambling during sleep, overwriting sensitive areas of RAM to reduce the risk of data extraction. This provides some protection while maintaining the quick-wake benefits of sleep.

Wake events present another security consideration. If a computer can wake from sleep due to network packets, magic packets in the case of wake-on-LAN, or other remote triggers, this creates a potential attack surface. An attacker who can send the appropriate wake signal could wake a sleeping computer and potentially exploit it. Disabling wake-on-LAN and other remote wake features on systems in untrusted environments reduces this risk.

Lock screens interact with power management in important ways. Most systems automatically lock when waking from sleep, requiring you to enter your password before accessing the system. This prevents someone from waking your computer and immediately accessing your data. However, the effectiveness depends on the lock screen being properly configured and on wake actually triggering the lock screen reliably.

Some systems support automatic encryption of RAM during sleep, a feature sometimes called encrypted sleep or sealed sleep. This provides additional security by ensuring that even the data in powered RAM is encrypted, though it typically has some impact on sleep and wake performance.

Understanding these security aspects helps you configure power management appropriately for your security needs, balancing convenience against the specific risks relevant to your situation.

Environmental and Energy Considerations

The environmental impact of computing is increasingly relevant, and power management decisions affect energy consumption and carbon footprint.

A typical desktop computer running at full power might consume one hundred to two hundred watts or more. Left running continuously, this represents significant energy consumption over time. A computer running twenty-four hours a day at one hundred fifty watts consumes about one hundred thirty-one kilowatt-hours per month, which in many locations translates to noticeable cost and environmental impact.

Sleep mode dramatically reduces this consumption. The same computer in sleep mode might consume just a few watts, reducing monthly consumption to perhaps a few kilowatt-hours. The savings become substantial when multiplied across millions of computers. This is why government energy efficiency programs and regulations encourage or sometimes mandate automatic sleep settings on computers.

However, the environmental calculation isn’t quite that simple. Manufacturing computers requires significant energy and resources. If aggressive power management through frequent sleep cycles reduces hardware lifespan, requiring earlier replacement, the manufacturing impact might offset some operational savings. This is an area of ongoing research and debate.

For most users and uses, the evidence suggests that using sleep mode appropriately provides net environmental benefits. The energy saved during sleep periods outweighs any minor impact on hardware longevity from the additional power cycling. Shutdown provides even greater savings for extended idle periods.

Organizations with many computers can achieve significant energy and cost savings through appropriate power management policies. Ensuring computers sleep when not in use, rather than running unnecessarily overnight or on weekends, can meaningfully reduce organizational energy consumption and carbon footprint.

Servers and data center equipment face different considerations, as they often must remain available continuously. However, even in data centers, sophisticated power management that reduces consumption during periods of low load can provide environmental benefits at scale.

Understanding the environmental dimension of power management decisions adds another factor to consider alongside convenience and functionality when configuring your systems.

Looking Forward: The Future of Power States

Power management continues to evolve, and understanding current trends suggests where things might be heading.

The line between different power states is blurring. Modern standby represents a state that’s somewhere between traditional sleep and full operation, maintaining network connectivity and allowing background tasks while still saving significant power compared to normal operation. Future systems might have even more gradual spectrums of power states rather than discrete sleep, hibernation, and shutdown options.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are beginning to influence power management. Systems might learn your usage patterns and predict when you’re likely to return, automatically choosing the most appropriate power state based on this prediction. A system might notice you typically take a coffee break from ten to ten-thirty each morning and automatically sleep during that period without you manually initiating it.

Improved battery technology and more power-efficient components might make the tradeoffs less critical. If a laptop can run for days on a charge even when not sleeping, the pressure to optimize power management reduces. However, even with improved efficiency, the environmental case for power management remains relevant.

Integration between operating systems and cloud services might change how we think about system state. If your documents, applications, and data are synchronized to the cloud continuously, losing local state becomes less catastrophic. This might make users more comfortable with shutdown rather than sleep or hibernation, knowing their work is preserved remotely.

New form factors like always-connected PCs that maintain cellular or WiFi connections even when sleeping, or convertible devices that transition between phone and computer modes, require evolution in how operating systems handle power states. The power management model that works for traditional desktop and laptop computers might not suit these new device categories.

Understanding current power management helps you appreciate both what’s possible today and how things might change in the future as technology evolves.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right State for Your Needs

Shutdown, sleep, and hibernation represent three fundamentally different approaches to the question of what your computer should do when you’re not actively using it. Each serves different needs and priorities, and understanding their technical implementations, advantages, and limitations empowers you to use them effectively.

Shutdown provides maximum power savings and a fresh start at the cost of losing current state and requiring full boot time to resume. Sleep provides instant resume and state preservation at the cost of continuous power consumption and vulnerability to power loss. Hibernation bridges these extremes, preserving state like sleep while achieving shutdown-level power savings at the cost of slower transitions.

The right choice depends on your specific situation: how long you’ll be away, whether you’re on battery or plugged in, how much you value instant resume versus power savings, and how critical your current working state is. For many users, a mixed approach works best, using sleep for short breaks, hibernation for longer periods, and shutdown for overnight or when a fresh start is desirable.

Modern operating systems make these choices easy, often defaulting to reasonable behaviors while providing configuration options for users who want more control. Understanding what happens behind the scenes when you select each option helps you make informed decisions rather than just accepting defaults.

Power management represents an ongoing balance between competing priorities: convenience versus power consumption, speed versus safety, availability versus energy efficiency. Operating systems continue to evolve more sophisticated approaches, but the fundamental concepts of sleep, hibernation, and shutdown remain central to how we interact with our computers.

The next time you close your laptop or walk away from your desktop, you’ll understand the options available and the complex engineering that makes each one work. Whether you choose to sleep, hibernate, or shut down, you’re making use of sophisticated power management capabilities that have evolved over decades to serve your needs while managing the precious resources of power and time.