Two Philosophies That Shape How Software Gets Created and Shared

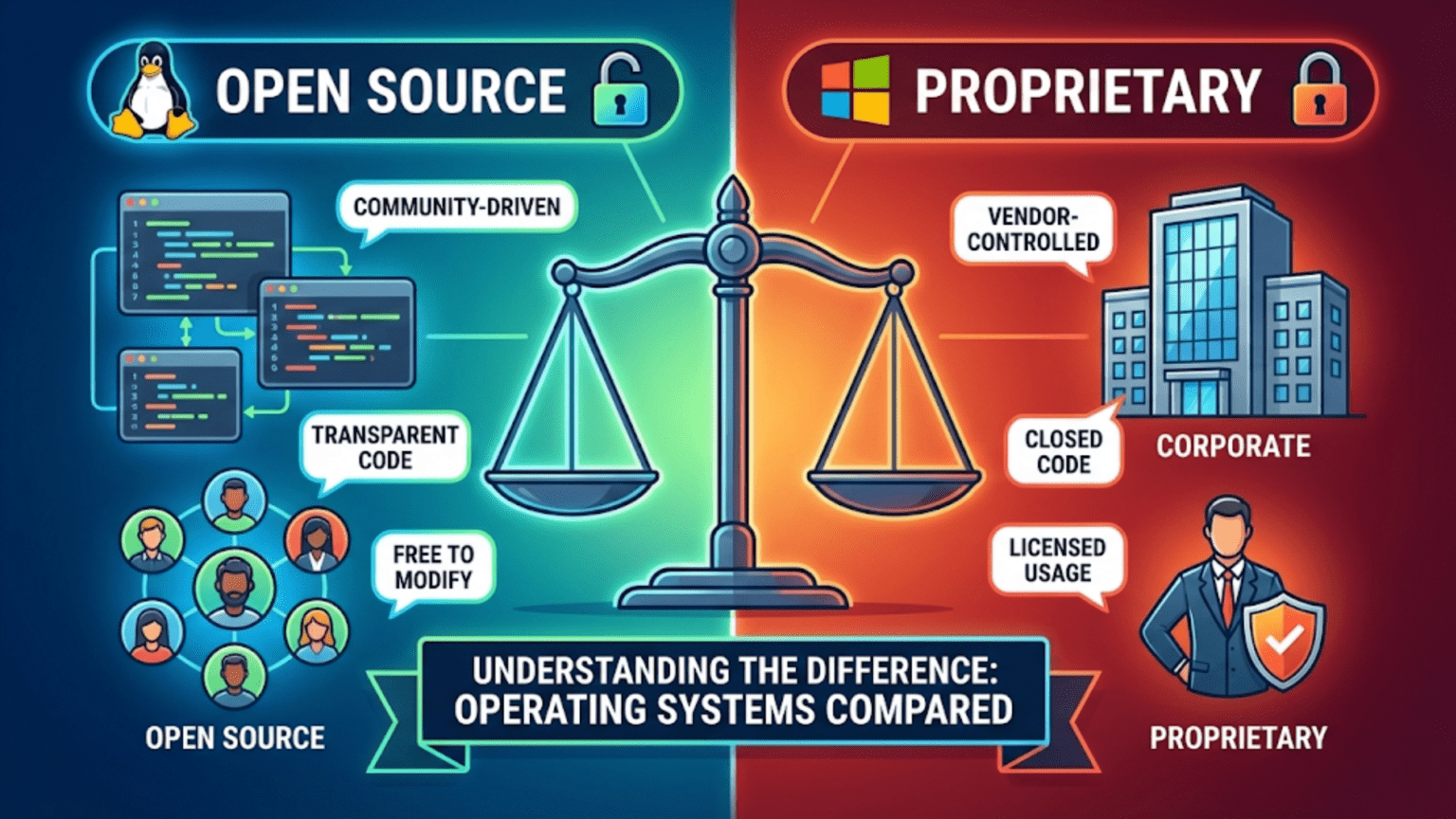

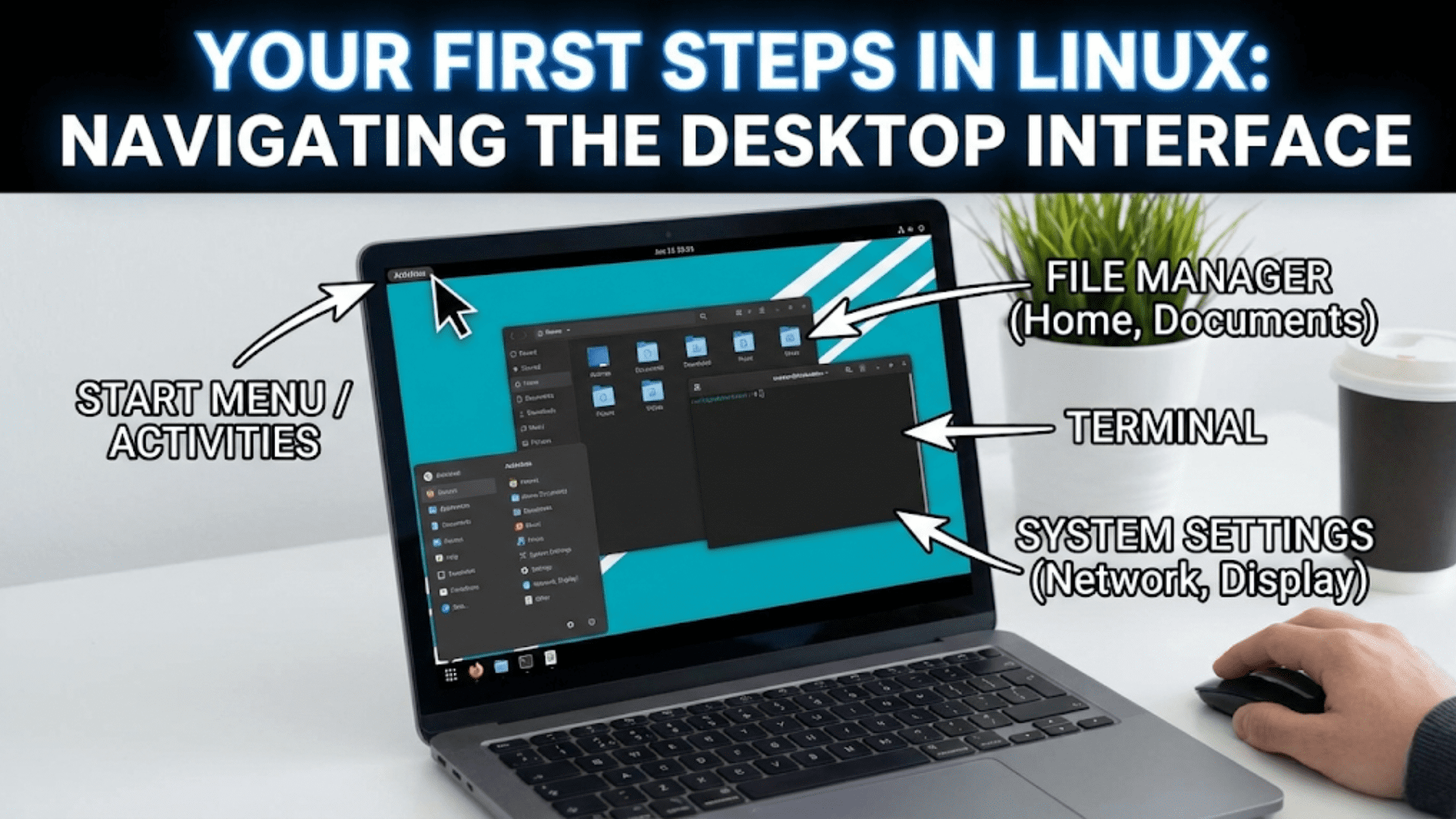

When you choose an operating system for your computer, you are making a decision that extends far beyond selecting features or user interface preferences. You are choosing between two fundamentally different approaches to how software gets created, distributed, and improved over time. Open source operating systems like Linux make their complete source code freely available for anyone to study, modify, and redistribute, fostering collaborative development by thousands of contributors worldwide. Proprietary operating systems like Windows and macOS keep their source code secret and tightly controlled, with development managed by companies that sell licenses granting permission to use the software but not to view or modify how it works internally. Understanding the distinction between these approaches reveals not just technical differences but also contrasting philosophies about software ownership, community involvement, and the relationship between companies and users.

The difference between open source and proprietary software traces to fundamentally different beliefs about how software should exist in society. The open source movement argues that software serves users best when its source code is available for anyone to examine, ensuring transparency about what the software does, enabling users to customize it for their specific needs, and allowing security experts worldwide to audit code for vulnerabilities. This transparency creates trust that closed source software cannot match because you must simply believe vendor claims about what proprietary software does rather than verifying those claims through code inspection. Open source advocates view software as a collaborative commons where improvements benefit everyone rather than enriching a single company, and they argue that this collaboration produces better software than closed commercial development can achieve.

Proprietary software advocates counter that commercial development creates the resources and incentives necessary for producing polished, reliable software that works well for typical users without requiring technical expertise. They argue that selling software licenses funds professional development teams, comprehensive testing, and user support that volunteer open source communities struggle to match. Proprietary vendors point to the billions of users who successfully run Windows and macOS as evidence that commercial software meets real needs effectively despite lacking open source transparency. They argue that intellectual property protections enabling companies to profit from their software innovations are essential for maintaining the investment needed to create sophisticated operating systems. Both perspectives have merit, and understanding the trade-offs helps you appreciate why both models persist and which might better serve your particular needs.

What Makes an Operating System Open Source?

The term open source refers to specific practices and licenses that govern how software can be used, modified, and distributed. Understanding these technicalities reveals what open source actually means beyond vague notions of free software.

Source code availability is the fundamental requirement. Open source operating systems provide their complete source code publicly, allowing anyone to download it, read it, and understand exactly how the software works at the most detailed level. This source code is the human-readable instructions that programmers write, which then get compiled into the machine-readable binary code that computers actually execute. With proprietary software, you receive only the compiled binary with no access to the original source. With open source software, you get both the binary and the source code that created it. This transparency means you can verify that the software does what it claims and nothing more, which matters tremendously for security and privacy since you do not have to trust vendor promises about what the software does.

Modification rights allow anyone to change open source software to fix bugs, add features, or customize behavior for specific needs. If you discover a problem in an open source operating system, you can modify the source code to correct it rather than waiting for the vendor to release a fix. If you need functionality the operating system does not provide, you can add it yourself or hire someone to add it for you. This freedom to modify contrasts sharply with proprietary software where modifying the code violates license terms and is usually technically impossible anyway since you lack the source code. The modification freedom makes open source particularly valuable for specialized applications where standard software does not quite fit requirements.

Redistribution permissions enable sharing both the original software and modified versions with others. You can give copies of Linux to friends, post modified versions on websites for others to download, or include open source operating systems with products you sell. This freedom to redistribute creates the collaborative development model where improvements made by anyone can benefit everyone else. Proprietary licenses typically prohibit redistribution entirely, requiring each user to obtain their own license directly from the vendor. The redistribution freedom explains how Linux distributions can exist—companies and organizations package Linux with additional software and improvements, then distribute complete operating systems without needing permission from Linux’s creator.

Specific open source licenses formalize these rights through legal documents that govern how the software can be used. The GNU General Public License, commonly used for Linux and much other open source software, requires that any distributed modifications also be open source, preventing someone from taking open source software, adding proprietary modifications, and selling the result as closed source. The MIT and BSD licenses are more permissive, allowing incorporation into proprietary software as long as the original copyright notice is retained. These licensing differences matter because they affect how open source software can be combined with other software and whether commercial use is restricted.

The open source development model typically involves communities of volunteer developers contributing to projects without direct financial compensation, though many contributors work for companies that support open source strategically. Development happens publicly with source code repositories visible to everyone, bug reports tracked openly, and discussions about design decisions accessible to all interested parties. This transparency contrasts with proprietary development which happens privately within companies with no public visibility into progress, priorities, or decision-making processes. The open development model enables anyone skilled enough to contribute improvements, creating diverse contributor bases that can exceed what single companies could fund.

What Defines Proprietary Operating Systems?

Proprietary operating systems take a completely different approach where companies maintain exclusive control over source code and how the software is used.

Closed source code means users receive only compiled binaries without access to the original human-readable source code. The company that developed the software keeps the source code secret, treating it as valuable intellectual property that competitors must not access. This secrecy prevents users from knowing exactly what the software does internally, requiring trust that the vendor’s software performs as advertised without hidden functionality. Companies argue this secrecy protects their competitive advantages and trade secrets, preventing competitors from copying innovations. Critics argue that secrecy enables privacy violations or security vulnerabilities that open source transparency would expose.

Licensing restrictions specify how users may and may not use the software, typically requiring payment for licenses that grant usage rights without transferring ownership. When you purchase Windows or macOS, you are buying a license to use the software under specific conditions, not buying the software itself. These licenses typically prohibit modifying the software, sharing it with others, or using it on more computers than the license covers. Violating license terms is legally prohibited regardless of technical ability to do so. The licensing model creates ongoing revenue streams for software companies through license sales and renewals.

Commercial development models fund proprietary operating systems through license sales that pay for teams of full-time professional developers, testers, designers, and support staff. Microsoft employs thousands of people working on Windows, and Apple similarly employs thousands working on macOS and iOS. This centralized professional development contrasts with open source’s distributed volunteer model. Proprietary advocates argue that commercial funding enables the polish, integration, and comprehensive testing that mass-market software requires, while open source advocates counter that community-driven development can match or exceed commercial quality for many purposes.

Vendor control means the company that owns the proprietary operating system makes all decisions about features, design, priorities, and direction without user input beyond market feedback. Users cannot directly change the operating system even if they want different features or behaviors. They can request changes through feedback channels, but the vendor decides whether to implement suggestions based on business considerations. This centralized control enables consistent vision and user experience but prevents the customization that open source allows.

Update and support structures for proprietary operating systems typically involve the vendor releasing updates on their schedule, providing technical support to paying customers, and controlling when older versions are discontinued. Users depend entirely on the vendor for security patches, bug fixes, and new features rather than having the option to implement changes themselves or hire others to do so. This creates dependency where the software’s longevity and quality depend on the vendor’s ongoing commitment and business health.

Security Implications: Transparency vs. Obscurity

Security represents one of the most debated aspects of open source versus proprietary software, with advocates on each side making compelling but contradictory arguments.

Open source proponents argue that transparency improves security because anyone can audit code for vulnerabilities, and with many eyes examining the code, problems are discovered and fixed faster than in proprietary software where only company employees review code. They point to the principle that security should not depend on secrecy about how systems work, a principle called Kerckhoffs’s principle established in the nineteenth century. Transparency enables independent security researchers to verify that software does what it claims and contains no hidden backdoors that could enable surveillance or unauthorized access. When vulnerabilities are discovered in open source software, the public nature of development means they are discussed openly and patches are typically available quickly.

Proprietary software advocates counter that obscurity provides some security benefit because attackers cannot examine the code to find vulnerabilities as easily as they can with open source where the code is publicly available. They argue that their paid professional security teams provide more thorough and systematic security review than scattered volunteer efforts. They point to their ability to coordinate complex security fixes across integrated software stacks without requiring community consensus. They note that open source software also has vulnerabilities despite public code availability, demonstrating that transparency alone does not prevent security problems.

The reality is nuanced and depends on implementation quality rather than the development model itself. Both open source and proprietary operating systems have experienced serious security vulnerabilities and both have mature security practices today. What matters more than the development model is whether development teams prioritize security, implement robust development practices, respond quickly to discovered vulnerabilities, and maintain software through regular security updates. Well-managed proprietary software can be very secure, and poorly maintained open source software can be quite vulnerable. The development model influences the process but does not determine the outcome.

Transparency does provide verification benefits that proprietary software cannot match. With open source, security experts and privacy advocates can verify that operating systems are not collecting data inappropriately or implementing backdoors. With proprietary software, you must trust vendor claims without ability to verify them independently. For users who value this verifiability, open source provides assurance that closed source cannot. For users who trust major vendors and value the convenience of commercial software, proprietary security may be perfectly adequate.

Cost Considerations: Free as in Beer and Free as in Freedom

Cost represents an obvious difference between open source and proprietary operating systems, though the full economic comparison is more subtle than simply free versus paid.

Open source operating systems are typically free to download and use with no licensing fees. You can obtain Linux distributions at no cost and install them on as many computers as you want without paying anything. This zero monetary cost makes open source attractive for individuals, educational institutions, and organizations managing many computers where licensing costs would be substantial. The freedom from licensing fees eliminates both the initial software cost and ongoing renewal expenses that some proprietary licenses require.

However, total cost of ownership includes more than software licensing. While the open source operating system itself is free, you might need to pay for technical support, training, custom development, or consulting to use it effectively. Organizations running Linux often purchase support contracts from companies like Red Hat or Canonical that provide professional assistance, which costs money though typically less than equivalent proprietary software licenses. The learning curve for transitioning to open source can represent real costs in training time and temporary productivity loss. These indirect costs mean that free software is not always the cheapest option when all factors are considered.

Proprietary operating systems have clear upfront costs through license purchases. Windows licenses cost money per computer, and macOS comes only with Apple hardware that costs more than commodity PCs running Linux or Windows. These costs are straightforward and predictable, which some organizations prefer over the uncertain costs of managing open source software themselves. The licensing fees fund professional support, comprehensive documentation, and polished user experiences that can reduce training costs and support burden.

The value of source code access has economic implications beyond licensing fees. Organizations with specific needs can modify open source operating systems rather than working around limitations in proprietary software or waiting for vendors to add features. This customization freedom can save money by enabling perfect fits rather than compromises. However, customization creates maintenance burden because custom modifications must be maintained through operating system updates, which requires ongoing development effort and expense.

The hidden cost of vendor lock-in affects proprietary software where switching to alternatives requires migrating data, retraining users, and replacing custom software built for the proprietary platform. Once you have invested heavily in Windows-specific software and trained users on Windows, switching to Linux involves substantial disruption and cost even though Linux itself is free. Open source reduces lock-in because you can switch between distributions more easily and can always fork the code if a project goes in directions you dislike.

Customization and Control: Flexibility vs. Consistency

The ability to modify and control your operating system differs dramatically between open source and proprietary software, affecting what you can accomplish and how systems can be adapted to specific needs.

Open source operating systems offer unlimited customization potential because you have complete access to all source code and the freedom to modify anything you want. If you dislike how something works, you can change it. If you need functionality that does not exist, you can add it. If you want to remove components you do not use, you can build custom versions without them. This flexibility enables creating highly specialized operating systems optimized for specific purposes like embedded systems, high-performance computing, or particular application domains. The Linux ecosystem demonstrates this diversity with hundreds of distributions customized for different uses, all built from the same core components but configured and packaged differently.

Proprietary operating systems provide limited customization confined to settings and preferences that the vendor has exposed. You can change wallpapers, adjust visual themes within provided options, and configure various behaviors, but you cannot change fundamental aspects of how the operating system works. If the vendor has not provided a setting for something you want to change, you cannot change it. This limitation prevents customization that conflicts with the vendor’s vision but also prevents adapting the software to unusual requirements the vendor did not anticipate.

Control over updates and versions differs significantly. With open source, you decide when and whether to install updates, and you can selectively apply specific changes while ignoring others. If an update introduces problems, you can revert it or fix the issues yourself. With proprietary software, you must accept the vendor’s update schedule and cannot easily revert problematic updates. Vendors occasionally force updates that users dislike, and users have little recourse beyond complaining or switching software entirely.

System integration and consistency represent areas where proprietary software often excels due to centralized control. Because one company designs all components to work together, proprietary operating systems typically provide more seamless integration and consistent user experience than open source software assembled from components created by different projects. Windows applications follow similar interface conventions because Microsoft provides guidelines and developers target a unified platform. Linux applications might look and behave differently because they come from various projects with different design philosophies. This consistency makes proprietary software easier to learn and use for typical users while open source flexibility better serves users with specific preferences.

Community and Support: Corporate Backing vs. Collaborative Networks

How you obtain help when problems arise differs substantially between open source and proprietary operating systems, affecting both the support experience and the relationship between users and developers.

Proprietary operating systems offer formal support channels where you can contact the vendor for help, often included with license purchases or available for additional fees. Microsoft and Apple provide official support through phone, chat, or in-person at stores. This official support provides accountability and guarantees someone will attempt to help with your problem, though the quality varies and solving complex problems might still be difficult. The formal relationship means you are a customer and the vendor has business incentives to keep you satisfied.

Open source operating systems rely primarily on community support through forums, mailing lists, chat channels, and documentation created by users and contributors. You ask questions on forums and hope knowledgeable community members volunteer answers. This model can work wonderfully when active communities respond helpfully, and many Linux users report that community support surpasses commercial support in responsiveness and expertise. However, you have no guarantee anyone will help with your specific problem, and if you ask in ways the community finds annoying, you might receive hostile responses rather than assistance.

Commercial support is available for open source operating systems through companies like Red Hat, Canonical, and SUSE that sell support contracts. These companies employ experts who provide professional assistance comparable to proprietary vendor support. This combines the benefits of open source software with the reliability of paid support, though it costs money and introduces vendor relationships similar to proprietary software. Organizations running critical systems on Linux typically purchase support contracts for this reason.

Documentation quality varies widely but follows different patterns in open source versus proprietary software. Proprietary vendors typically produce comprehensive official documentation covering all features systematically, maintained by technical writers who ensure accuracy and clarity. Open source documentation is often more scattered across wikis, man pages, and various websites created by different contributors. Some open source projects have excellent documentation rivaling commercial software, while others have sparse or outdated documentation that assumes expert knowledge. The variability can frustrate new users but also means multiple perspectives might explain concepts differently, helping different learning styles.

The community’s role in improving software differs dramatically. With proprietary software, users can report bugs and request features, but only the vendor can actually change the software. With open source, users who are programmers can fix bugs themselves and contribute improvements back to the project. Even non-programmers can hire developers to implement custom features or fixes. This democratization of development means that open source software can be shaped by its users to a degree impossible with proprietary software.

Practical Considerations: Which Should You Choose?

Choosing between open source and proprietary operating systems requires considering your specific needs, skills, and priorities rather than blindly following ideology from either camp.

For typical home users who want computers that just work without requiring technical knowledge, proprietary operating systems often provide easier experiences. Windows and macOS are specifically designed for non-technical users with polished interfaces, extensive commercial software availability, and support infrastructures that help when things go wrong. The learning curve is gentler and compatibility with peripherals and software is broader because vendors actively pursue universal compatibility as a business priority.

For technical users, enthusiasts, and people who value customization and transparency, open source operating systems offer capabilities that proprietary software cannot match. The ability to see exactly how your operating system works, modify anything you want, and participate in development communities appeals to users who want control and understanding rather than just convenience. Linux provides tools and flexibility that technical users appreciate even if it sometimes requires more effort to achieve what proprietary systems do out of the box.

For organizations and businesses, the choice depends on specific requirements around cost, support, customization, and integration with existing systems. Enterprises with substantial Windows or macOS investments face high switching costs that might not justify changing regardless of open source benefits. Organizations building specialized systems or managing thousands of servers might prefer Linux’s customization and zero licensing costs even though they purchase support contracts. The decision requires analyzing total cost of ownership, required features, available expertise, and long-term strategic goals rather than simply comparing initial license costs.

For developers and programmers, open source operating systems provide development environments with powerful tools, scripting capabilities, and programming language support that many developers prefer. The Unix heritage of Linux and macOS provides command-line environments that enable automation and scripting workflows difficult on Windows, though Windows has improved this with Windows Subsystem for Linux. The programming tools available free on Linux rival expensive commercial equivalents, making it attractive for software development.

For privacy-conscious users concerned about data collection and surveillance, open source transparency provides assurances that proprietary software cannot. You can verify that open source operating systems are not collecting data inappropriately or implementing backdoors because the source code is available for audit. Proprietary software requires trusting vendor privacy claims without ability to verify them, which some users find unacceptable regardless of other benefits.

Understanding the differences between open source and proprietary operating systems reveals that both approaches have legitimate strengths and weaknesses rather than one being universally superior. Open source provides transparency, customization, and freedom from vendor control at the cost of sometimes requiring more technical expertise and offering less polished experiences for non-technical users. Proprietary software provides convenience, consistency, and commercial support at the cost of vendor dependence and limited customization. The right choice depends on your specific situation, skills, priorities, and needs rather than ideological commitment to either development model. Both open source and proprietary operating systems will continue evolving, and understanding their fundamental differences helps you make informed choices about which better serves your computing needs.