SEO METADATA

SEO Title: System Libraries Explained: Their Critical Role in Operating Systems

Meta Description: Learn what system libraries are and how they help operating systems function. Discover shared libraries, DLLs, runtime libraries, and how they enable software to work efficiently.

Focus Keyword: system libraries in operating systems

Secondary Keywords: what are system libraries, shared libraries explained, DLL files, runtime libraries, how libraries work

Article Category: Operating Systems – Foundational Concepts

Target Audience: Beginners to intermediate users, students, aspiring developers

Word Count: ~5,100 words

Reading Time: 20-26 minutes

The Role of System Libraries in Operating System Function

The Shared Code That Makes Software Possible

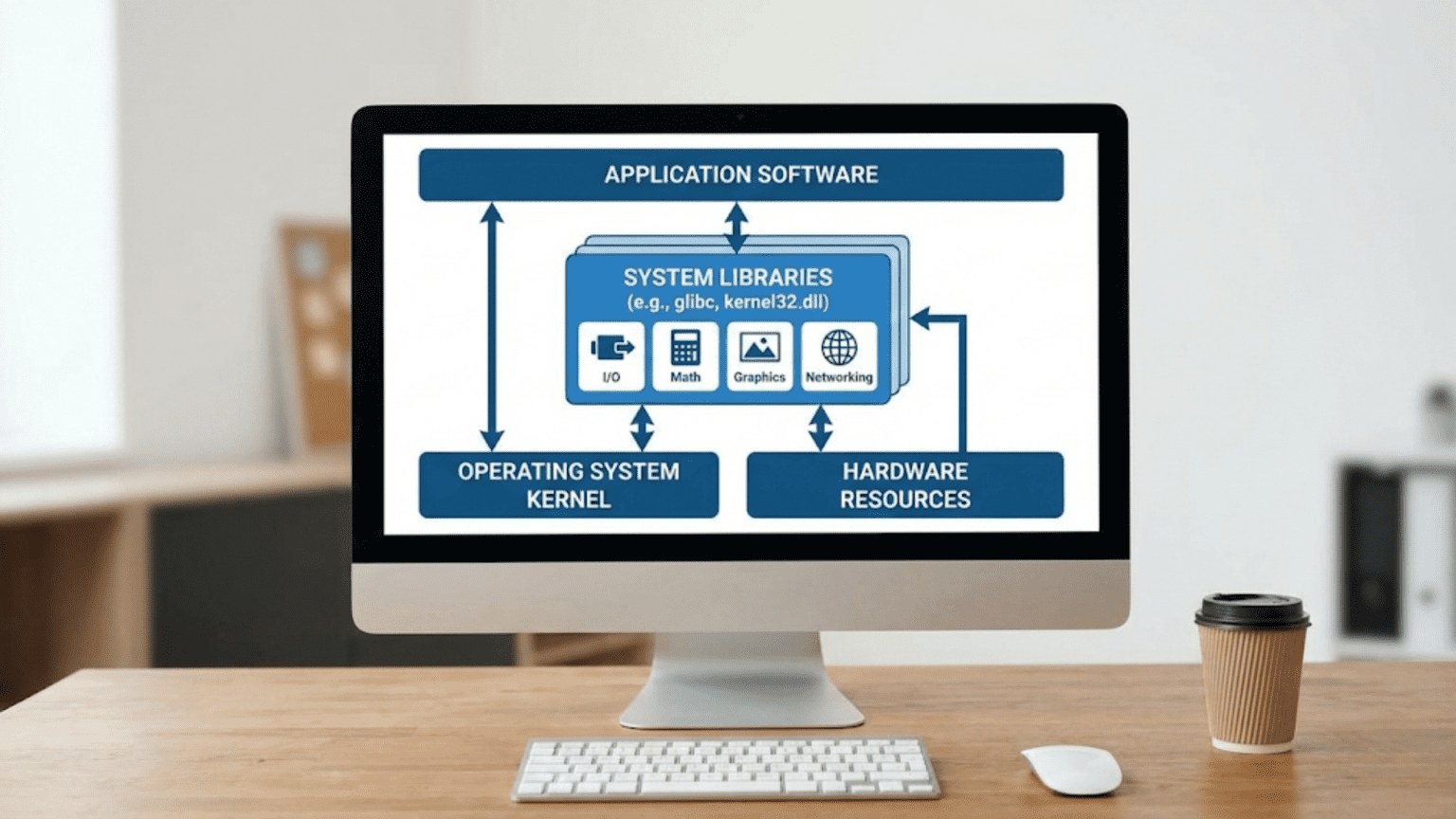

When you launch an application on your computer, whether it is a web browser, word processor, or game, that program must accomplish countless tasks that go far beyond its unique features. It needs to create windows and draw graphical interfaces on screen. It needs to read and write files using the file system. It needs to allocate memory, manage text strings, perform mathematical calculations, and handle countless other fundamental operations. Rather than every program implementing all these basic capabilities from scratch, operating systems provide system libraries that contain pre-written, tested, and optimized code for common operations that many programs need. These libraries act as repositories of shared functionality that applications can draw upon, dramatically simplifying software development and making programs smaller and more efficient than they would be if each had to implement every capability independently.

System libraries represent one of the most elegant solutions in computing, solving multiple problems simultaneously through code sharing. From a practical perspective, libraries prevent duplicated effort where thousands of programmers would otherwise separately implement the same basic functionality over and over. A single well-tested library function for reading files can serve thousands of applications rather than each application containing its own file-reading code with potential bugs and inefficiencies. From a resource perspective, libraries reduce memory consumption because the same library code loaded once in memory serves multiple applications rather than each application carrying duplicate copies of similar code. From a maintenance perspective, fixing bugs or improving performance in library code automatically benefits all applications using that library without requiring changes to the applications themselves. Understanding system libraries reveals fundamental principles about how software builds upon foundations that others have created, enabling sophisticated applications through layers of abstraction.

The distinction between system libraries provided by the operating system and application-specific libraries that individual programs include is important for understanding software architecture. System libraries like the C standard library, graphics libraries, or network communication libraries come with the operating system and provide foundational capabilities that virtually all programs need. Applications can rely on these system libraries being present and standardized, enabling portability across different computers running the same operating system. Application-specific libraries serve unique needs of particular programs and are distributed with those programs rather than being part of the operating system. Both types of libraries use similar technical mechanisms, but system libraries deserve special attention because they form the foundation that enables the entire software ecosystem on a platform.

What System Libraries Contain: Fundamental Capabilities

Understanding what functionality system libraries provide reveals how they enable applications to accomplish complex tasks without implementing everything from scratch. These libraries contain the building blocks that programs combine to create their unique features.

The standard C library, often called libc on Unix-like systems or the C Runtime Library on Windows, provides fundamental capabilities that nearly every program uses. This library includes functions for memory allocation like malloc and free that request and release memory from the operating system, string manipulation functions like strcpy and strlen for working with text, mathematical functions like sqrt and sin for computations, and file input and output functions like fopen and fread for accessing the file system. These capabilities are so fundamental that programs written in C and many other languages depend on them implicitly. Even programs that do not directly call these functions likely use language features that internally rely on standard library implementations. The ubiquity of standard library functionality makes it the most essential system library that enables basic program operation.

Graphics libraries provide capabilities for drawing user interfaces, rendering images, and creating visual output. On Windows, the Graphics Device Interface and its successors provide functions for drawing shapes, displaying text, managing windows, and handling mouse and keyboard input. On Linux, libraries like X11, GTK, and Qt enable creating graphical applications. On macOS, Cocoa provides the graphics and user interface framework. These graphics libraries abstract away the complexity of directly controlling graphics hardware, providing high-level functions for drawing that work across different graphics cards and display configurations. Applications call library functions to create windows or draw rectangles rather than sending low-level commands to graphics processors, making graphics programming accessible without requiring deep understanding of graphics hardware.

Network libraries enable applications to communicate over networks without implementing complex protocols themselves. Socket libraries provide functions for creating network connections, sending and receiving data, and managing communication channels. Higher-level libraries implement protocols like HTTP for web communication, SSL/TLS for encrypted communication, or FTP for file transfer. These networking capabilities would be extremely complex to implement correctly from scratch, with subtle requirements around error handling, security, and protocol compliance. Network libraries encapsulate this complexity behind relatively simple interfaces where applications can make network connections and transfer data without worrying about the intricate details of how network protocols work.

Threading libraries provide support for creating and managing multiple threads of execution within programs, enabling applications to perform multiple tasks concurrently. POSIX threads on Unix-like systems and the Windows threading API provide functions for creating threads, synchronizing their execution through locks and semaphores, and coordinating their work. Threading is notoriously difficult to implement correctly because of subtle race conditions and synchronization issues, making robust threading libraries essential for applications that need concurrent execution. Rather than every programmer implementing threading primitives from scratch with all the bugs that would introduce, shared threading libraries provide tested implementations that developers can rely on.

Math libraries extend beyond basic arithmetic to provide advanced mathematical functions including trigonometry, logarithms, complex number arithmetic, and statistical functions. Scientific and engineering applications depend heavily on these mathematical capabilities, and having standardized library implementations ensures consistent accurate results across different programs and platforms. Math libraries often include optimizations that exploit specific processor features to accelerate calculations, providing performance benefits that individual application developers might not achieve implementing these functions themselves.

Static vs. Dynamic Libraries: Different Approaches to Code Sharing

Libraries can be incorporated into programs through two fundamentally different mechanisms that have important implications for how programs are built, distributed, and executed. Understanding static and dynamic linking reveals trade-offs that operating system designers and application developers must navigate.

Static libraries become part of the executable program during compilation, with library code copied directly into the application’s executable file. When you compile a program that uses static libraries, the compiler identifies which library functions the program calls, extracts those specific functions from the library files, and includes their machine code in the final executable. The resulting program contains everything it needs to run including all library code it depends on, making it self-contained. Static linking simplifies deployment because you can copy the executable to any compatible system and run it without worrying about whether required libraries are installed. The program will always use the specific library versions it was compiled with, ensuring consistent behavior regardless of what other library versions might be installed on the system.

However, static linking has significant disadvantages. Each program that statically links a library carries its own copy of that library code, wasting disk space and memory because identical library code appears in multiple executables and loads into memory multiple times when several statically linked programs run simultaneously. If library bugs are discovered and fixed, every statically linked program must be recompiled and redistributed to benefit from the fixes, whereas dynamically linked programs automatically use updated libraries without requiring recompilation. Static linking also produces larger executable files because they must contain all library code they depend on rather than just references to external libraries.

Dynamic libraries, called shared libraries on Unix-like systems and Dynamic Link Libraries or DLLs on Windows, are loaded at runtime when programs execute rather than being incorporated during compilation. Programs compiled with dynamic linking contain references to external library files that must be present on the system when the program runs. When you launch a dynamically linked program, the operating system’s dynamic linker loads the required library files into memory and resolves the references in the program to point to the loaded library code. Multiple programs can share a single copy of library code loaded in memory, dramatically reducing memory consumption compared to static linking where each program carries duplicate copies.

Dynamic linking provides several important benefits. Library updates automatically benefit all dynamically linked programs without requiring recompilation because the programs load whatever library version is installed on the system at runtime. This simplifies distributing bug fixes and security updates for libraries because updating the shared library file immediately affects all programs using it. Dynamic linking also reduces executable file sizes because programs contain only small stubs referencing library functions rather than the complete library code, making programs faster to download and requiring less storage space. The memory savings from sharing library code among multiple programs significantly reduces total memory requirements on systems running many programs simultaneously.

However, dynamic linking introduces complexity and potential problems. Programs depend on required libraries being installed on the system, and if libraries are missing or incompatible versions are installed, programs might fail to launch or behave incorrectly. This dependency on external files creates the infamous “DLL hell” problem on Windows where different applications require different versions of the same library, and installing one application might overwrite libraries that other applications depend on, breaking those applications. The startup time for dynamically linked programs is slightly longer because the dynamic linker must locate and load libraries, resolve references, and perform any necessary relocations before the program can begin executing.

How Dynamic Linking Works: The Loading Process

Understanding the mechanics of how operating systems load and link dynamic libraries reveals sophisticated machinery working behind the scenes every time you launch a program. This process happens so quickly and reliably that users never notice it, but it represents significant engineering enabling efficient code sharing.

When you launch a dynamically linked program, the operating system begins by loading the executable file into memory. Early in this process, before the program actually starts executing, the operating system’s dynamic linker examines the executable to determine what libraries it depends on. This dependency information is stored in the executable during compilation, listing by name all libraries the program needs. The dynamic linker must locate these library files somewhere on the system, typically searching standard directories like /lib and /usr/lib on Linux or System32 on Windows, and optionally checking additional directories specified by environment variables.

After locating the required libraries, the dynamic linker loads them into memory alongside the program. If a library is already loaded in memory from another running program, the operating system can share that existing copy rather than loading a duplicate, achieving the memory savings that make dynamic linking attractive. The linker must ensure that libraries load at appropriate memory addresses that do not conflict with the program or other libraries, which sometimes requires relocating the library to different addresses than were assumed during compilation.

Symbol resolution connects references in the program to actual function and variable addresses in the loaded libraries. During compilation, when the program calls a library function, the compiler generates a reference to that function by name without knowing where the function will be located at runtime. The dynamic linker finds each referenced symbol in the appropriate library, determines its address in the loaded library, and updates the program’s references to point to the actual addresses. This resolution process establishes the connections that allow program code to call library functions successfully.

Lazy binding or lazy symbol resolution optimizes startup time by deferring symbol resolution until functions are actually called rather than resolving everything during program launch. The first time the program calls a particular library function, a small amount of linker code executes to resolve that symbol and update the reference, then subsequent calls go directly to the resolved address without linker involvement. This lazy approach avoids resolving symbols for functions that the program never actually calls during a particular execution, reducing startup overhead. Some systems support eager binding where all symbols are resolved at load time, providing slightly faster function calls at the cost of slower program startup.

Dependencies between libraries must also be handled because libraries themselves can depend on other libraries, creating chains of dependencies. When the dynamic linker loads a library that depends on other libraries, it must recursively load those dependencies as well, ensuring the entire dependency graph is satisfied before the program begins executing. Managing these complex dependency relationships requires sophisticated algorithms to avoid circular dependencies and ensure libraries load in appropriate orders.

Library Versioning and Compatibility

As libraries evolve over time with bug fixes, new features, and improvements, managing different versions becomes critically important to ensure programs continue working even as libraries change. The mechanisms operating systems use to handle library versioning balance between enabling library improvements and maintaining compatibility with existing programs.

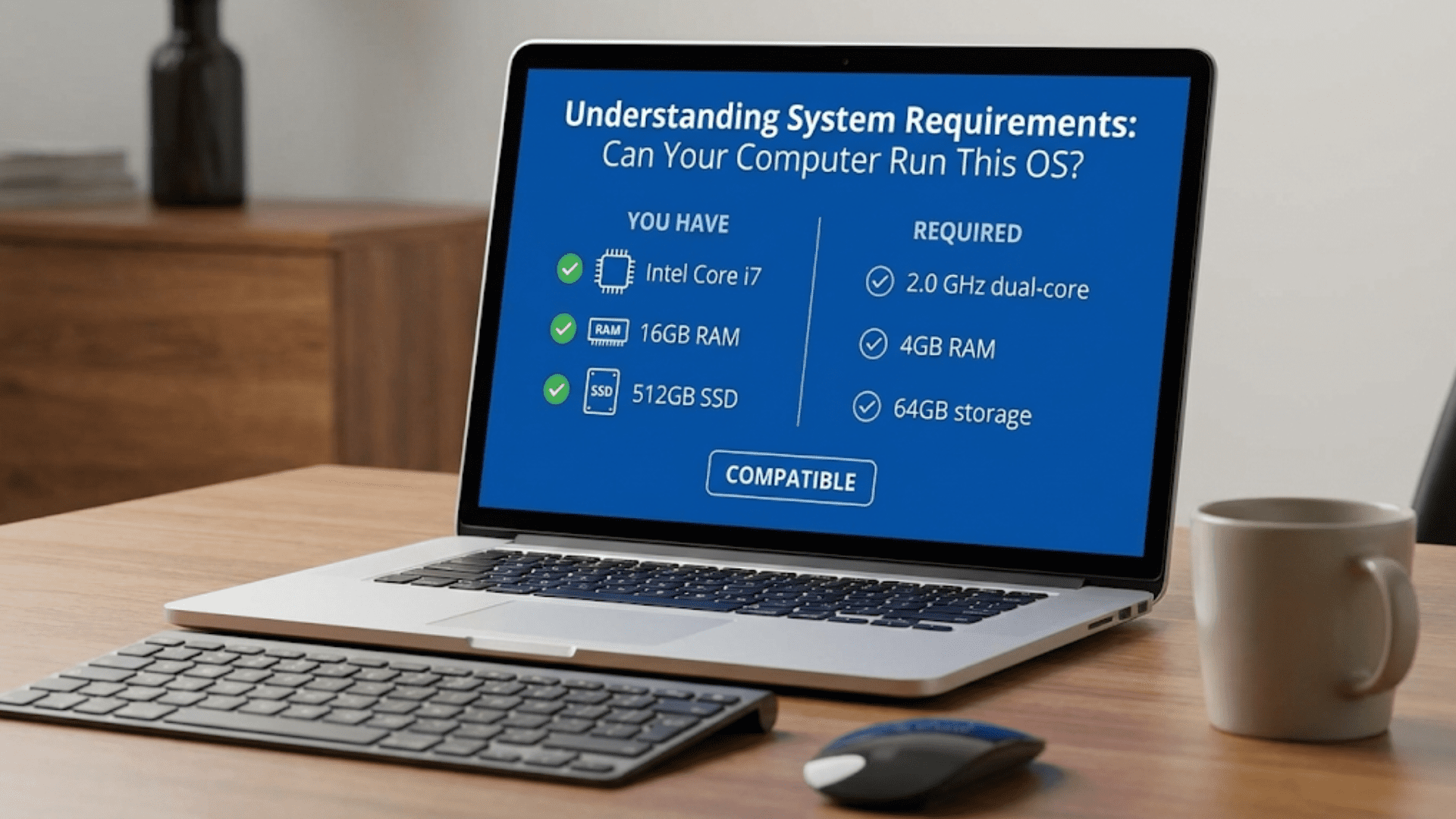

Semantic versioning provides a standardized way to communicate what has changed in library versions through version numbers structured as major.minor.patch. Incrementing the patch version indicates bug fixes that do not change the library’s interface. Incrementing the minor version indicates new features were added but existing functionality remains compatible. Incrementing the major version indicates incompatible changes that might break programs compiled against previous versions. This versioning scheme helps developers and users understand what impact updating a library might have on existing software.

Binary compatibility means that programs compiled against one library version can use a different compatible version without recompilation. Maintaining binary compatibility requires that library updates preserve the exact function signatures, data structure layouts, and behavioral contracts that existing programs depend on. Adding new functions maintains binary compatibility because existing programs simply do not call them. However, changing how existing functions work, modifying data structure layouts, or removing functions breaks binary compatibility and requires programs to be recompiled against the new library version.

Sonames on Unix-like systems embed version information in library file names, allowing multiple incompatible versions to coexist on the same system. A library file might be named libexample.so.1.2.3 where “1” is the major version that must match for binary compatibility. Programs link against the soname libexample.so.1 which is a symbolic link pointing to a specific compatible version like libexample.so.1.2.3. When the library is updated with compatible changes to version 1.2.4, updating the symbolic link makes programs automatically use the new version. When an incompatible version 2.0.0 is released, it installs as libexample.so.2 without conflicting with the 1.x versions, allowing programs compiled for different major versions to coexist.

Side-by-side versioning on Windows allows different library versions to install in separate directories, with programs explicitly specifying which version they need. Application manifests embedded in executables declare what library versions the program requires, and the operating system’s assembly resolution mechanism locates and loads the appropriate versions. This approach prevents the DLL hell problem where installing one application’s libraries overwrites another’s, though it requires more disk space because multiple versions of the same library exist on the system rather than being shared.

System Library Security and Updates

Because system libraries are shared by many applications and often run with significant privileges, their security is critically important. Vulnerabilities in widely used libraries can affect numerous applications, making library security a high-stakes concern for operating systems.

Security vulnerabilities in libraries can have widespread impact because a single vulnerable library might be used by hundreds of applications on a system. A buffer overflow in a common string handling function could potentially be exploited through any application that uses that function with untrusted input. This amplification of impact makes library security crucial, and operating system vendors invest heavily in auditing system libraries and responding quickly when vulnerabilities are discovered.

Security updates for libraries automatically benefit all dynamically linked applications that use them, which is a major advantage of dynamic linking for security. When a library vulnerability is discovered and fixed, updating the shared library on the system immediately protects all applications using it without requiring individual application updates. This centralized updating significantly simplifies security maintenance compared to static linking where every application would need individual updates to incorporate fixed library code.

Library loading security prevents attacks where malicious libraries are substituted for legitimate ones. Operating systems implement protections like requiring libraries to be in trusted directories, verifying digital signatures on library files, and ignoring environment variables that specify library search paths when programs run with elevated privileges. These protections ensure that programs load authentic system libraries rather than trojan libraries that attackers might try to inject.

The Evolution of System Libraries

System libraries have evolved significantly since the early days of computing, with modern libraries providing far more sophisticated capabilities and better organization than their predecessors. Understanding this evolution provides context for why contemporary libraries work as they do.

Early libraries were simple collections of commonly used subroutines that programmers could include in their programs to avoid rewriting basic functionality. These primitive libraries offered little abstraction or standardization, and using them often required deep understanding of the underlying hardware. The progression from these simple collections to modern comprehensive system libraries with well-designed abstractions represents decades of refinement based on experience with what capabilities programs need and how to provide them effectively.

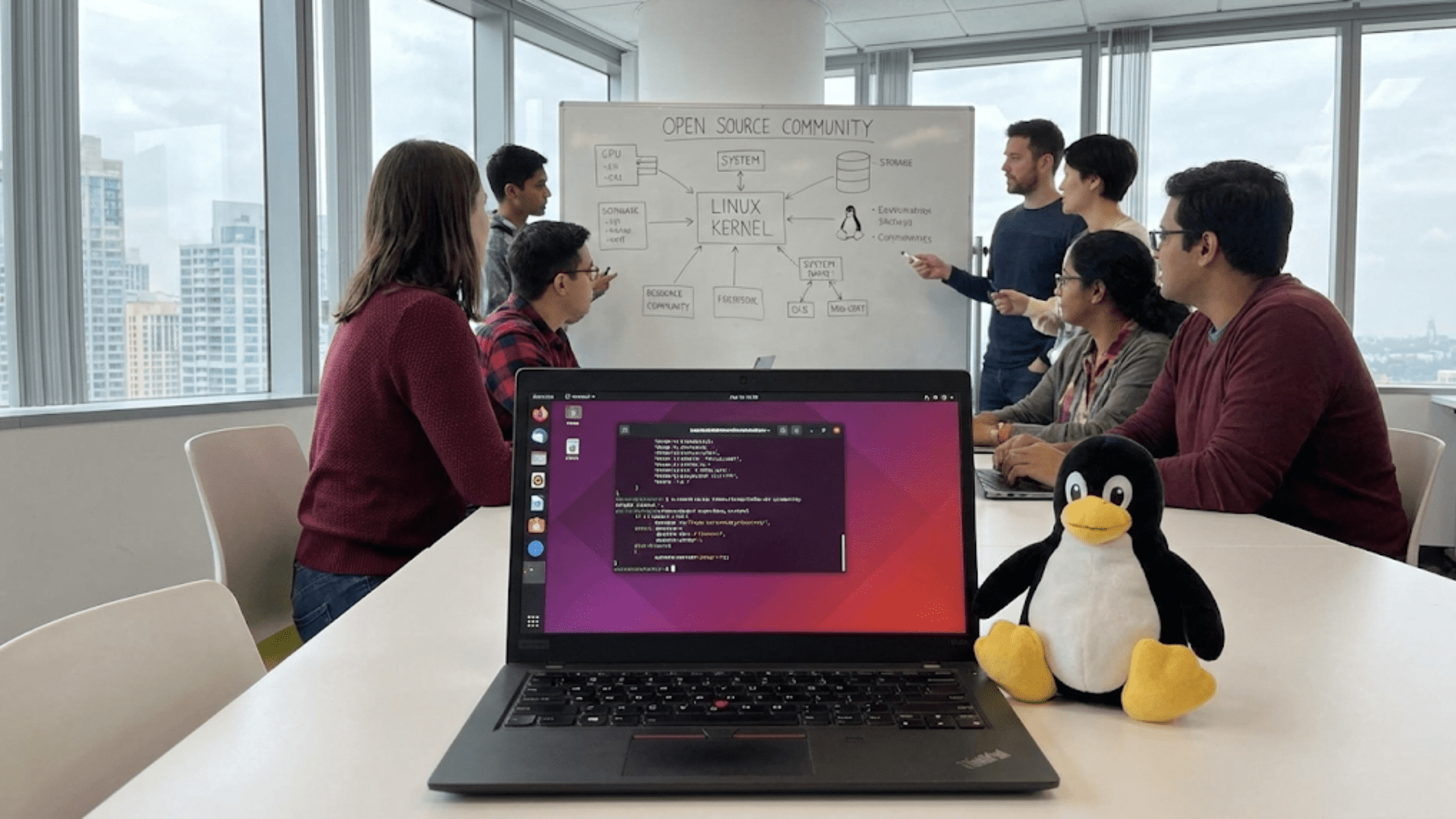

Standardization efforts like POSIX defined portable library interfaces that multiple operating systems could implement compatibly, enabling source code portability where programs written against standard library interfaces could be recompiled for different operating systems without modification. This standardization allowed software developers to target a standard rather than specific operating systems, dramatically expanding the potential audience for their software.

Object-oriented and higher-level libraries built upon lower-level system libraries to provide richer abstractions and easier programming models. Rather than just providing basic functions, modern libraries offer complete frameworks with object-oriented designs that manage resources, handle errors consistently, and provide declarative interfaces where programmers specify what they want rather than implementing detailed procedures for achieving it.

Best Practices for Using System Libraries

Developers and users both benefit from understanding how to work with system libraries effectively, whether that is writing programs that use libraries well or maintaining systems with complex library dependencies.

Developers should prefer using system libraries over implementing functionality from scratch whenever appropriate libraries exist. The testing, optimization, and maintenance that system libraries receive typically far exceeds what individual developers can achieve, making library use both more reliable and more efficient than custom implementations. However, this principle requires judging when libraries actually fit needs rather than dogmatically using libraries even when they are poor fits for specific requirements.

Users should keep system libraries updated to benefit from bug fixes and security patches that library updates provide. Operating system update mechanisms typically handle system library updates automatically, making this maintenance largely transparent. However, understanding that library updates are important helps users appreciate why installing operating system updates matters even when they do not add visible new features.

Understanding library dependencies helps when troubleshooting application problems. If a program fails to launch with error messages about missing libraries, knowing how to locate and install required libraries or understanding why incompatible library versions cause problems enables resolving issues that might otherwise seem mysterious. Tools that show library dependencies help diagnose these problems systematically rather than requiring guesswork.

System libraries represent essential infrastructure enabling the sophisticated software ecosystem that modern computing depends upon. By providing shared implementations of common functionality, libraries make software development more efficient, reduce resource consumption through code sharing, and improve quality through centralized testing and maintenance of widely used capabilities. The next time you launch a program and it successfully creates windows, loads files, and communicates over networks, recognize that much of that functionality comes from system libraries working invisibly to provide the foundations that applications build upon. Understanding these libraries reveals how operating systems enable the rich software experiences users expect through carefully designed shared components that serve the entire software ecosystem.