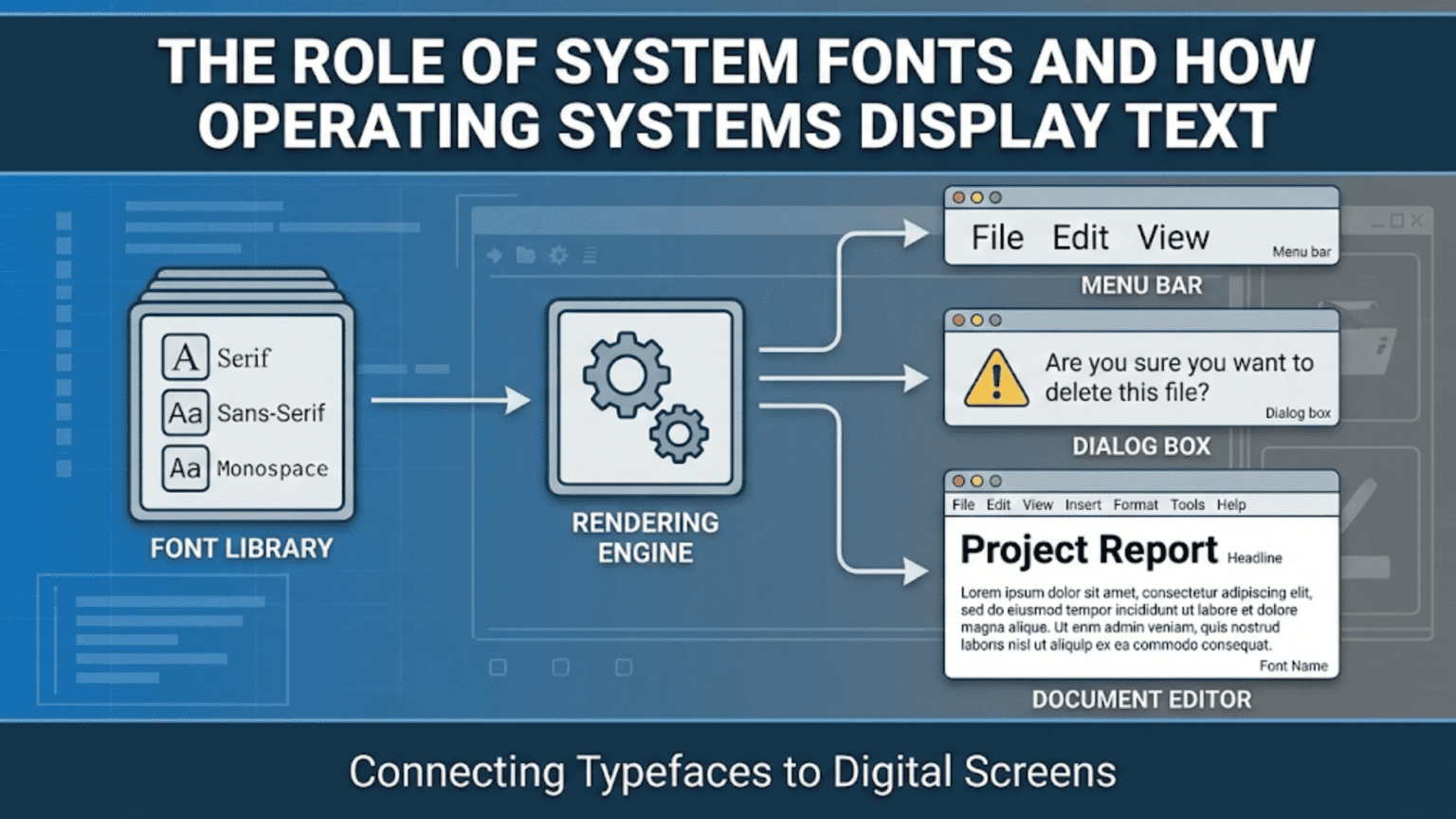

System fonts are collections of typefaces that operating systems install and manage for use by applications, the OS itself, and the user interface. Operating systems handle text display through font rendering engines that convert font files into pixels on screen, applying techniques like antialiasing, hinting, and subpixel rendering to make text legible at small sizes and across different display types. The OS provides font management services including font discovery, loading, caching, and fallback selection when specific characters aren’t available in the requested font.

Every character you read on a screen—whether in a web browser, document editor, operating system menu, or any other application—is the result of a complex chain of operations involving font files, rendering engines, display technologies, and operating system services working together to transform abstract character codes into visible, legible pixels. The words on your screen aren’t simply stored as images; they’re generated dynamically from mathematical descriptions of letterforms, processed through sophisticated algorithms that optimize legibility for specific screen resolutions and sizes, and cached intelligently to avoid repeating expensive calculations. Text rendering is one of the most computationally demanding aspects of everyday computing, and the quality of an operating system’s font management and rendering significantly impacts the readability, aesthetics, and feel of every application that displays text.

Operating systems play a central role in this process, maintaining libraries of installed fonts available to all applications, providing rendering engines that transform font data into screen pixels, managing font caches that prevent repeated rendering overhead, implementing fallback mechanisms that ensure text displays correctly even when specific fonts are unavailable, and providing APIs through which applications request text rendering services. The sophistication required to display readable text across displays ranging from 72 DPI monitors to 300+ DPI retina screens, in sizes from tiny captions to large headings, in hundreds of languages with diverse writing systems and typographic traditions, represents a remarkable engineering achievement built into every modern operating system. This comprehensive guide explores how operating systems manage fonts and render text, covering font formats and technology, rendering techniques, font management across platforms, internationalization challenges, and how different operating systems have approached these challenges with different philosophies and implementations.

What Fonts Are and How They’re Stored

Fonts are structured files containing mathematical descriptions of letterforms along with metadata and instructions for rendering them at various sizes and qualities.

At the most fundamental level, a font defines how each character (or glyph) in a character set should look. Modern fonts use vector descriptions—mathematical curves (typically Bézier curves) that define the outlines of each glyph. These outline descriptions are resolution-independent: the same mathematical description renders correctly at 8 points for a footnote or 72 points for a headline. The operating system’s font rendering engine converts these outlines to the specific pixel grid of the display at whatever size is requested.

Font formats have evolved significantly over computing history. TrueType (.ttf) was developed jointly by Apple and Microsoft in the late 1980s as an alternative to Adobe’s PostScript Type 1 fonts. TrueType uses quadratic Bézier curves and includes a sophisticated hinting system—instructions embedded in the font that guide the rendering engine to align glyph features (stems, serifs, x-heights) to pixel boundaries at small sizes. TrueType became the dominant font format for operating systems throughout the 1990s.

OpenType (.otf) was developed jointly by Microsoft and Adobe as a successor to both TrueType and Type 1, combining the best of both. OpenType can contain either TrueType or cubic Bézier curve outlines, supports far more glyphs per font (up to 65,536 versus TrueType’s 65,536 theoretical but practical limitation), includes advanced typographic features like ligatures, contextual alternates, small caps, and old-style numerals, and uses a single cross-platform file format. Modern fonts are predominantly OpenType, often with the .otf extension for cubic bezier (CFF) variants and .ttf extension for TrueType quadratic bezier variants within the OpenType container.

Variable fonts are a modern OpenType extension enabling a single font file to contain a continuous range of variations across one or more axes like weight (thin to black), width (condensed to expanded), optical size, and slant. Traditional font families required separate files for each combination (Regular, Bold, Italic, Bold Italic), while variable fonts interpolate smoothly between extremes. Variable fonts reduce the file count applications must load and enable finer-grained typography control. Operating systems supporting variable fonts (Windows 10 1709+, macOS 10.13+, iOS 11+, modern Linux) can take advantage of this expressiveness.

Web fonts (.woff, .woff2) are optimized versions of font formats for web delivery, compressed and structured for efficient download and use by web browsers. WOFF2 (Web Open Font Format 2) achieves roughly 30% better compression than WOFF, making web typography practical at scale. Browsers request web fonts through CSS and the browser’s font loading system (typically part of the OS rendering engine) handles downloading, caching, and using them like installed system fonts.

Font metadata embedded in font files includes the font’s name (family name, style name), designer and foundry information, licensing information, supported Unicode ranges, and OS/2 table data used by Windows for font classification and rendering decisions. The operating system reads this metadata to organize fonts in font managers, determine font properties for API queries, and make rendering decisions.

How Font Rendering Works

Font rendering—converting mathematical font descriptions to screen pixels—involves multiple sophisticated stages, each addressing specific challenges in making text legible on digital displays.

Rasterization converts vector outlines to pixel grids at specific sizes. For a character like “a” at 12 pixels tall, the rendering engine scales the font’s vector outline to that size and determines which pixels fall inside or outside the outline. Straight rasterization (each pixel is simply on or off) produces jagged, stairstepped letterforms because the pixel grid is too coarse to faithfully represent smooth curves at small sizes. This aliasing problem motivated the development of antialiasing techniques.

Antialiasing smooths rasterized text by using shades of gray (on non-color displays) or intermediate intensities between background and foreground colors. Instead of each pixel being fully black or white, pixels near outline edges become gray, proportional to how much of that pixel’s area falls inside the glyph outline. Grayscale antialiasing makes text appear smoother, particularly curves and diagonal strokes, though it can make text appear slightly blurry at very small sizes where insufficient pixels exist to represent details.

Subpixel rendering (ClearType on Windows, various implementations elsewhere) exploits the physical structure of LCD displays, where each pixel consists of three colored subpixels—red, green, and blue—arranged horizontally. By addressing individual subpixels rather than whole pixels, effective horizontal resolution triples for text rendering. A 96 DPI display effectively becomes 288 DPI horizontally for text rendering purposes. ClearType text appears significantly sharper than grayscale antialiased text, particularly for horizontal stroke widths and character spacing. However, subpixel rendering is sensitive to monitor orientation and subpixel layout, potentially producing color fringing on some displays.

Font hinting (or instructing) addresses the challenge that scaled font outlines often don’t align well with the pixel grid at small sizes, causing inconsistent stem widths, blurry features, and visual unevenness. Hints are instructions embedded in fonts (primarily TrueType fonts) that guide the rasterizer to adjust glyph shapes at specific sizes to align features to pixel boundaries. For example, a hint might snap all vertical stems to exactly 1 pixel wide at a given size, ensuring consistent appearance. Well-hinted fonts look significantly better at screen sizes (9-14 points) than poorly hinted ones. Hinting requires significant expertise and effort from font designers, and high-quality commercial fonts invest substantially in hinting.

FreeType is the open-source font rendering library used by Linux, Android, and many other platforms. FreeType implements TrueType and OpenType rasterization with antialiasing and hinting support, configurable quality-versus-performance tradeoffs, and subpixel rendering. FreeType’s rendering quality is highly configurable through settings exposed by compositing managers and applications. Different Linux distributions configure FreeType differently, resulting in varying text rendering quality across distributions.

High-DPI rendering has changed font rendering challenges significantly. On Retina displays (200+ DPI), simple antialiasing approaches produce excellent results because the pixel grid is fine enough to represent font details well. Many HiDPI display users actually disable subpixel rendering (which provides less benefit at high DPI) in favor of simpler grayscale rendering that looks excellent at high resolutions. The rendering pipeline must also handle the concept of “points” versus “pixels”—a 12-point font on a 2x Retina display renders to 24 pixels tall but should occupy the same physical space as 12 points at 1x.

GPU acceleration increasingly handles font rendering in modern systems. Traditional font rendering happened entirely on the CPU. Modern systems use GPU rendering (through Direct2D on Windows, Core Graphics on macOS, or OpenGL/Vulkan on Linux) to accelerate text composition. GPU rendering enables hardware-accelerated compositing of text with other graphical elements, smooth text animation, and better performance for text-heavy applications.

Font Management in Operating Systems

Operating systems provide font management infrastructure that handles installation, discovery, caching, and providing fonts to applications through standardized APIs.

Font installation registers fonts with the operating system so they become available to all applications. On Windows, installing a font copies it to C:\Windows\Fonts and registers it in the Windows Registry. On macOS, fonts can be installed in /Library/Fonts (system-wide), ~/Library/Fonts (user-specific), or /System/Library/Fonts (system fonts, read-only). On Linux following FreeType and fontconfig conventions, fonts are typically installed in /usr/share/fonts (system), /usr/local/share/fonts, or ~/.fonts or ~/.local/share/fonts for user fonts, with font directories registered in fontconfig configuration files.

Font discovery services allow applications to enumerate available fonts and query their properties without knowing file locations. Windows provides the GDI and DirectWrite font enumeration APIs. macOS provides CoreText and the older ATS (Apple Type Services). Linux applications typically use fontconfig for font discovery. These APIs allow applications to query “what fonts are installed,” filter by properties (serif/sans-serif, bold availability, language support), and retrieve font file paths for loading.

Font caching prevents repeated parsing of font files, which is expensive for complex fonts with many glyphs. Operating systems maintain font caches that store parsed font metadata, glyph outlines, and rendered glyph bitmaps at common sizes. Windows maintains a font cache in the Windows Font Cache Service, macOS has its own font cache infrastructure, and FreeType on Linux includes caching through fontconfig. Cache invalidation occurs when fonts are installed or removed, triggering cache rebuild on next access.

Font fallback handles the situation where a requested font doesn’t contain a glyph for a specific character. When an application requests to render a Chinese character using a Western font that contains no Chinese glyphs, the font system must find an alternative font containing that character. The OS maintains font fallback lists—ordered sequences of fonts to try when the primary font lacks needed glyphs. These fallback lists are carefully curated to ensure text in any Unicode character from any language can be displayed, even when the primary font doesn’t support that script.

System fonts are fonts the operating system installs and uses for its own interface elements. Every OS ships with a curated set of fonts covering the interface needs and major writing systems of its supported languages. Windows includes fonts like Segoe UI (the primary UI font since Windows Vista), Calibri, Cambria, and hundreds more. macOS uses San Francisco (custom Apple font) for its UI, along with Helvetica Neue, Times New Roman, and many others. Linux distributions typically ship with open-source fonts like DejaVu, Liberation, and Noto.

User font installation adds custom fonts for specific needs. Designers, publishers, and typographically conscious users install professional fonts from foundries like Adobe Fonts, Google Fonts, or commercial sources. Installing fonts through the OS makes them available to all applications. Recent macOS versions added per-app font management allowing different fonts to be activated for different applications, useful when some applications conflict over font versions.

Font activation and deactivation allows enabling fonts only when needed, reducing menu clutter and avoiding conflicts. Font management applications like FontExplorer X (Mac), NexusFont (Windows), or fontconfig manipulation on Linux allow managing large font libraries by activating subsets and keeping others dormant. This is particularly valuable for design professionals with libraries of hundreds or thousands of fonts.

Text Rendering Across Different Operating Systems

Each major operating system has developed distinctive approaches to font rendering, reflecting different priorities and philosophies about typography quality.

Windows text rendering has evolved through multiple generations. Early Windows used GDI (Graphics Device Interface) with basic antialiasing. Windows XP introduced ClearType, Microsoft’s subpixel rendering technology that dramatically improved on-screen text quality, particularly at the common 96 DPI resolution of monitors of that era. Windows 7 and later default to DirectWrite, a GPU-accelerated text rendering API replacing GDI for modern applications. DirectWrite uses ClearType with additional improvements, supports natural rendering (using subpixel antialiasing aligned to the glyph outline rather than the pixel grid), and integrates with Direct2D for hardware-accelerated compositing. Windows has traditionally prioritized horizontal pixel sharpness through ClearType, resulting in text that some find crisp and others find overly mechanical compared to macOS.

macOS text rendering has consistently prioritized faithful reproduction of the designer’s intent, rendering glyphs as close to their mathematical descriptions as possible rather than aggressively snapping features to pixel boundaries. macOS uses Core Graphics and CoreText, with Quartz as the underlying compositing engine. macOS traditionally used stronger antialiasing that some find blurry at low resolutions but which renders text more consistently across sizes. As Apple transitioned to Retina displays, the high pixel density made this approach produce beautiful results—at 220+ DPI, antialiasing without aggressive pixel-snapping produces very smooth, accurate text rendering. Apple gradually changed rendering over macOS versions, removing subpixel antialiasing from macOS Mojave on Retina displays. The San Francisco font family, custom-designed by Apple, is optimized for the rendering characteristics of Apple displays.

Linux text rendering quality varies significantly based on configuration and distribution choices. FreeType handles the actual rendering with highly configurable quality parameters. Fontconfig manages font discovery and selection with extensive customization. Desktop environments like GNOME and KDE configure rendering defaults, but users can fine-tune aggressively. Linux can achieve rendering quality comparable to Windows or macOS with appropriate configuration, but default configurations vary widely. The FreeType project has incrementally improved rendering quality by implementing better autohinting (for fonts lacking TrueType hints) and refining antialiasing algorithms.

Platform-specific fonts mean that documents looking perfect on one OS may look different on another. Documents created on Windows using Calibri look different on macOS (which may substitute a different font) or Linux (where Calibri may not be installed). Web standards addressed this through web fonts, and cross-platform document formats like PDF embed fonts entirely to avoid substitution. Desktop applications that must work across platforms either bundle specific fonts or use only fonts available across all target platforms.

Font smoothing preferences allow users to adjust rendering to personal taste. Windows allows configuring ClearType settings through the ClearType Text Tuner (accessed via Control Panel or by searching “ClearType”). macOS has limited user-accessible rendering settings but macOS Ventura and later allow adjusting font smoothing in Accessibility settings. Linux users can configure FreeType settings through fontconfig files or GNOME/KDE system settings, adjusting hinting strength, antialiasing mode, and subpixel order.

International Text and Complex Scripts

Modern operating systems must handle text in hundreds of languages, many with writing systems fundamentally different from the Latin alphabet, presenting unique rendering challenges.

Unicode is the universal character encoding standard used by modern operating systems, assigning unique code points to over 140,000 characters covering virtually all writing systems in active use. Unicode enables a single text rendering architecture to handle Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, Devanagari, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and countless other scripts. The OS’s font system must manage the fact that no single font covers all Unicode characters, requiring fallback to different fonts for different characters within the same text string.

Bidirectional text (bidi) presents a complex rendering challenge because languages like Arabic and Hebrew write right-to-left while Latin scripts write left-to-right. When mixed in a single paragraph, the text direction changes, and the layout engine must implement the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm to determine the display order of characters. Operating system text layout engines (DirectWrite on Windows, CoreText on macOS, Pango on Linux) implement bidi support, allowing correct rendering of mixed-direction text without application developers implementing these algorithms themselves.

Complex script shaping is necessary for scripts where character appearance depends on context. Arabic characters have different forms depending on their position within a word (initial, medial, final, isolated). Devanagari (used for Hindi and many other South Asian languages) combines consonants into conjunct characters and attaches vowel signs in positions above, below, or beside base characters. Ligatures in Arabic and Indic scripts merge multiple characters into combined forms. Text shaping engines (HarfBuzz on Linux, CoreText shaping on macOS, DirectWrite shaping on Windows) implement OpenType shaping rules that transform Unicode character sequences into positioned glyph sequences for these complex scripts.

CJK (Chinese, Japanese, Korean) text presents both font size and rendering challenges. CJK characters are complex ideographs requiring many more strokes than Latin characters, demanding higher resolutions to render legibly. The enormous character sets (tens of thousands of characters in Chinese) require large font files—a complete CJK font might be 20-50MB versus 100-300KB for a Latin font. Operating systems include CJK fonts appropriate for each locale, and the fallback system ensures users see correct characters even when an application’s primary font lacks CJK coverage. Google’s Noto font project specifically aims to eliminate missing characters (tofu squares) for all Unicode-supported scripts.

Emoji rendering represents a modern extension of complex script support. Emoji characters in Unicode must render as colorful, expressive images within text flows. Operating systems include emoji fonts—Apple Color Emoji on macOS/iOS, Segoe UI Emoji on Windows, Noto Emoji on Android—that render emoji as color images. These fonts use special font technologies like COLR/CPAL (layered colored glyphs), CBDT/CBLC (color bitmap data), or sbix (Apple-specific color bitmaps) to store color glyph data within the OpenType format. Text rendering engines handle emoji seamlessly within text, selecting the emoji font for appropriate code points while using other fonts for surrounding text characters.

Font licensing and distribution affects which fonts are available across platforms. Commercial fonts require licenses restricting distribution. Microsoft includes fonts like Arial, Times New Roman, and Calibri with Windows but doesn’t license them for other platforms. macOS includes different fonts. Linux distributions typically use free open-source fonts (Liberation Series, DejaVu, GNU FreeFont) that provide metrically compatible alternatives to common commercial fonts, or Google’s Noto fonts providing comprehensive Unicode coverage. These licensing realities explain why the same document looks different across platforms.

Font APIs for Developers

Applications access fonts through operating system APIs that abstract the complexity of font management and rendering.

The Windows DirectWrite API is the modern Windows text layout and rendering API, providing GPU-accelerated text rendering with support for OpenType features, ClearType, and complex script shaping. Applications create IDWriteFactory, enumerate fonts through IDWriteFontCollection, create text formats specifying font and size, measure text using IDWriteTextLayout, and render to Direct2D surfaces. DirectWrite handles all the complexity of font selection, fallback, shaping, and rendering, letting applications focus on layout logic.

The older Windows GDI text APIs remain available for compatibility. CreateFont and SelectObject select fonts into device contexts, TextOut and DrawText render strings, and GetTextMetrics provides font measurements. GDI text rendering is simpler to use but less capable than DirectWrite, lacking good support for complex scripts, OpenType features, or hardware acceleration.

macOS CoreText provides the low-level text layout and rendering API, handling shaping, layout, and rendering of text. CTFont represents fonts, CTFrame handles multi-line layout, CTLine manages single lines, CTRun handles runs of uniformly styled text, and CTFontDescriptor queries available fonts. CoreText is powerful but complex; many macOS applications use the higher-level NSAttributedString and NSTextView (AppKit) or UILabel and UITextView (UIKit on iOS) which internally use CoreText.

Linux fontconfig provides font discovery and configuration but not rendering itself. Applications use fontconfig to find fonts matching criteria (name, weight, style, language coverage), then load font files with FreeType, perform shaping with HarfBuzz, and render using their own pipeline or through higher-level toolkits. GTK (used by GNOME applications) and Qt (KDE applications) provide complete text rendering stacks built on these libraries, abstracting the complexity for application developers.

CSS font properties on the web correspond to OS font capabilities. font-family specifies preferred fonts with fallbacks, font-weight controls weight, font-style controls style, font-size sets size, and font-variant exposes OpenType features. Browsers implement these CSS properties using OS text rendering services, translating CSS font requests into appropriate OS API calls. Web font loading (@font-face) extends the OS font system with dynamically loaded web fonts, handled by browser font loading infrastructure.

Font Performance Considerations

Font rendering consumes significant computational resources, and operating systems implement various optimizations to minimize its performance impact.

Glyph caching stores rendered glyph bitmaps so each unique glyph-at-size combination need only be rendered once. The first time “a” at 12px in Helvetica Regular is needed, the rendering engine converts the vector outline to pixels and stores the result. Subsequent requests for the same glyph retrieve the cached bitmap instantly, avoiding expensive vector-to-raster conversion. Glyph caches are limited in size and use LRU (Least Recently Used) eviction—removing least-recently-accessed entries when space is needed.

Text layout caching stores computed text layout for strings, avoiding re-layout when the same text is displayed repeatedly. If a UI label displays the same text continuously, layout calculation (line breaking, glyph positioning, bidirectional reordering) only needs to happen once. Cached layouts are invalidated when text content, style, or available width changes.

Font subsetting reduces font file sizes for web delivery by including only the glyphs actually used by a particular page or application. A web page using a font for English text might include only the 100 or so glyphs needed for that language rather than the full 2000-glyph font. Subsetting reduces download size significantly, improving web typography performance. Browsers automatically use partial font loading when fonts support it, fetching additional glyph ranges on demand.

Lazy font loading defers loading font data until actually needed. Large fonts (especially CJK fonts) load slowly. Font systems load metadata (font name, supported characters, basic metrics) immediately but defer loading glyph outline data until a specific glyph is needed. This lazy loading makes initial font enumeration fast while still providing access to complete font data when needed.

Conclusion

Fonts and text rendering represent a remarkably complex intersection of typography, computer graphics, internationalization, and operating system services that nonetheless appears completely transparent to users. The journey from Unicode character codes to legible pixels on screen involves font file parsing, outline scaling, hinting interpretation, antialiasing, subpixel rendering, shaping for complex scripts, fallback font selection, caching at multiple levels, and hardware-accelerated compositing—all happening in milliseconds every time text is displayed.

Operating systems’ role as the foundation of all text display makes their font management and rendering quality architecturally significant. The distinctive rendering approaches of Windows (traditionally emphasizing ClearType sharpness), macOS (favoring faithful typeface reproduction, especially on Retina displays), and Linux (highly configurable through FreeType and fontconfig) reflect genuine philosophical differences about typography quality and user preference. As displays universally trend toward higher pixel densities, some of these historical differences matter less—at 4K resolution on a 24-inch monitor, essentially any modern rendering approach produces beautiful text—while font management, complex script support, and variable font capabilities become increasingly important differentiators.

For users, understanding font systems enables better typography choices in documents, troubleshooting font display issues, managing font collections, and appreciating why some applications’ text looks better than others. For developers, understanding how operating systems render text informs performance optimization (minimizing font loading and layout recalculation), internationalization (using OS text layout APIs rather than implementing shaping independently), and cross-platform consistency. For everyone, every moment of reading text on any screen represents this invisible, sophisticated infrastructure working correctly—making legible, beautiful text from mathematical descriptions and operating system services.

Summary Table: Font Systems Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | macOS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Font Location | C:\Windows\Fonts | /System/Library/Fonts (read-only)<br>/Library/Fonts (system-wide)<br>~/Library/Fonts (user) | /usr/share/fonts/<br>/usr/local/share/fonts/<br>~/.fonts/ or ~/.local/share/fonts/ |

| Font Discovery API | GDI (legacy), DirectWrite (IDWriteFontCollection) | CoreText (CTFontManager), ATS (legacy) | fontconfig |

| Text Rendering Engine | DirectWrite (modern), GDI (legacy) | Core Graphics + CoreText | FreeType + HarfBuzz + Pango/Cairo |

| Antialiasing Approach | ClearType (subpixel, default) | Grayscale antialiasing (Retina default), subpixel on non-Retina | Configurable: none, grayscale, subpixel (RGBA/BGR/VRGB) |

| Font Hinting | Full native TrueType hints (aggressive pixel snapping) | Minimal (prefer faithful outlines) | Configurable: slight, medium, full, none |

| Shaping Engine | DirectWrite + OpenType shaping | CoreText shaping engine | HarfBuzz |

| Complex Script Support | Excellent (built into DirectWrite) | Excellent (built into CoreText) | Excellent (HarfBuzz + Pango) |

| Default UI Font | Segoe UI (Windows Vista+)<br>Segoe UI Variable (Windows 11) | San Francisco (SF Pro, SF Compact) | Varies: Cantarell (GNOME), Noto Sans (many distros) |

| Font Cache Location | Windows Font Cache Service | /Library/Caches/com.apple.ATS/ | ~/.cache/fontconfig/ |

| Font Manager (Built-in) | Settings > Personalization > Fonts | Font Book.app | None (distro-specific: gnome-font-viewer, KDE font settings) |

| Variable Font Support | Yes (Windows 10 1709+) | Yes (macOS 10.13+) | Yes (FreeType 2.8+) |

| Emoji Font | Segoe UI Emoji | Apple Color Emoji | Noto Color Emoji (common), Twemoji |

| GPU Acceleration | DirectWrite + Direct2D | Core Animation + Core Graphics | Varies by toolkit (Skia, Cairo with GL) |

| ClearType Tuning | ClearType Text Tuner (Control Panel) | Limited (Accessibility settings) | fontconfig subpixel settings |

Common Font Formats and OS Support:

| Format | Extension | Description | Windows | macOS | Linux | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrueType | .ttf | Apple/Microsoft vector outlines, quadratic Bézier | Full | Full | Full | Screen use, hinted fonts |

| OpenType (CFF) | .otf | Adobe/Microsoft cubic Bézier outlines | Full | Full | Full | Print, professional typography |

| OpenType (TT) | .ttf | TrueType in OpenType container | Full | Full | Full | Universal use |

| Variable Font | .ttf/.otf | Single file, multiple weights/styles | Win 10 1709+ | macOS 10.13+ | FreeType 2.8+ | Modern applications |

| WOFF | .woff | Compressed web font | Browsers | Browsers | Browsers | Web typography |

| WOFF2 | .woff2 | Better-compressed web font | Browsers | Browsers | Browsers | Web typography (preferred) |

| Color (COLR/CPAL) | .ttf/.otf | Layered color glyphs | Win 8.1+ | macOS 10.13+ | FreeType 2.10+ | Emoji, color icons |

| Color (CBDT/CBLC) | .ttf/.otf | Color bitmap glyphs | Limited | Limited | FreeType | Android emoji |

| Type 1 (PostScript) | .pfb/.pfm | Adobe legacy format | Legacy | Legacy (deprecated) | FreeType | Legacy compatibility |

| Bitmap | .fon | Fixed-size bitmap fonts | Legacy | No | Limited | Terminal use |