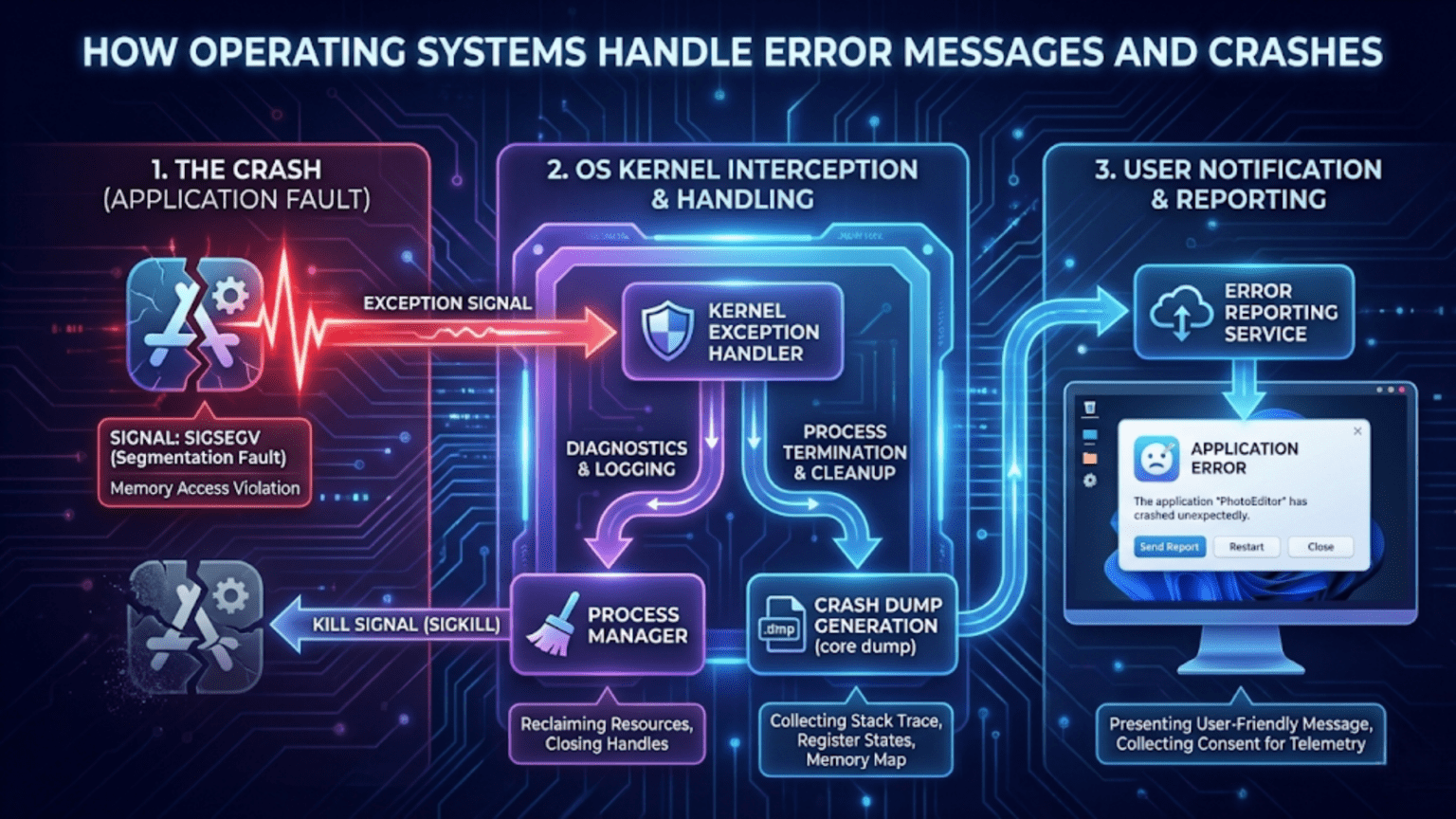

Operating systems handle error messages and crashes through multiple layers of detection, reporting, and recovery mechanisms including exception handlers that catch program errors, crash dump generation that captures system state for analysis, error logging systems that record problems, automatic restart and recovery procedures that restore functionality, and protective mechanisms like memory isolation that prevent one program’s crash from affecting the entire system, ensuring system stability and providing information needed for troubleshooting.

When a program crashes, when the dreaded Blue Screen of Death appears on Windows, when macOS displays a kernel panic, or when Linux logs a segmentation fault, your operating system is detecting, handling, and attempting to recover from errors that threaten system stability or data integrity. These error situations range from minor application glitches to catastrophic system failures, and how the operating system responds determines whether you lose unsaved work, whether the entire system becomes unusable, and whether developers and administrators can diagnose and fix the underlying problems. Error handling represents one of the most critical responsibilities of modern operating systems—without robust error detection and recovery mechanisms, computers would be unreliable, unstable, and frustrating to use. Understanding how operating systems handle errors and crashes reveals the sophisticated protective infrastructure working constantly behind the scenes to maintain system stability and recoverability.

Error handling in operating systems occurs at multiple levels, from low-level hardware exceptions caught by the processor to high-level application error reporting dialogs. The operating system must detect errors when they occur, protect the rest of the system from being affected by the error, preserve information about what went wrong for later analysis, attempt recovery when possible, and inform users or administrators about the problem appropriately. Different types of errors require different handling strategies—a division by zero in an application can be contained to that application, while a kernel panic requires immediate system halt to prevent data corruption. The complexity of modern operating systems, with millions of lines of code running in kernel mode with direct hardware access and countless applications running simultaneously, makes comprehensive error handling both challenging and essential. This guide explores the various types of errors operating systems encounter, the mechanisms used to detect and handle them, how crash information is captured and reported, recovery and restart procedures, and how different operating systems approach the challenge of maintaining stability in the face of inevitable errors.

Types of Errors and Failures

Operating systems must handle numerous categories of errors, each with different characteristics, severity levels, and appropriate responses.

Hardware errors occur when physical computer components malfunction or fail. Memory errors from failing RAM chips can cause data corruption—the CPU reads different data than what was written. Disk errors from bad sectors or failing drives prevent reading or writing data reliably. CPU errors from overheating or manufacturing defects can cause incorrect computation. Bus errors occur when the CPU attempts to access memory at addresses the hardware bus cannot handle. Hardware errors are particularly serious because they indicate physical problems that software alone cannot fix, though operating systems implement detection mechanisms like ECC (Error-Correcting Code) memory to identify and sometimes correct memory errors automatically.

Software bugs represent programming errors in either the operating system itself or applications running on it. Null pointer dereferences occur when programs attempt to access memory through a pointer that hasn’t been initialized, causing segmentation faults or access violations. Buffer overflows happen when programs write data beyond allocated memory boundaries, potentially corrupting other data or allowing security exploits. Logic errors cause incorrect behavior even though the program doesn’t crash—calculations produce wrong results, data gets corrupted, or the program enters infinite loops. Race conditions in multithreaded programs cause unpredictable behavior depending on timing of concurrent operations. Deadlocks occur when two or more processes wait indefinitely for resources held by each other, causing the system or applications to hang.

Memory access violations happen when programs attempt to access memory they’re not allowed to access. Reading or writing to memory belonging to other processes violates memory protection, triggering access violations (Windows) or segmentation faults (Unix-like systems). Attempting to write to read-only memory causes write protection faults. Accessing unmapped memory—addresses that don’t correspond to any physical RAM or memory-mapped device—causes page faults that cannot be resolved. The operating system’s memory management unit (MMU) detects these violations and triggers protective responses.

Resource exhaustion errors occur when the system runs out of critical resources. Out of memory (OOM) situations happen when all available RAM and swap space are consumed. Out of disk space prevents writing new files or expanding existing ones. File descriptor exhaustion occurs when all available file handles are in use. Process table exhaustion happens when the maximum number of processes are already running. These errors are often transient—freeing resources allows operations to succeed—but can also indicate system capacity problems or resource leaks.

Kernel panics or system crashes represent the most severe errors where the operating system itself encounters a problem it cannot recover from safely. These might result from kernel bugs, corrupted kernel data structures, critical hardware failures, or situations where continuing operation would risk data corruption. When the kernel panics, it halts all operation to prevent further damage, displays error information, and typically creates a crash dump for later analysis.

Application crashes occur when individual programs fail without affecting the overall system. Unhandled exceptions, assertion failures, or termination by the operating system (due to policy violations or resource limits) cause application crashes. Modern operating systems isolate applications so their crashes don’t affect other programs or the system core.

Configuration errors arise from incorrect system settings, missing files, or incompatible software versions. Services fail to start because configuration files contain syntax errors or reference non-existent resources. Applications crash because required DLL or shared library versions are missing or incompatible. These errors often manifest during startup or when specific features are activated.

Error Detection Mechanisms

Operating systems employ various mechanisms to detect errors as they occur, enabling timely response before errors cause extensive damage.

Hardware exceptions are the lowest-level error detection mechanism. Modern CPUs implement exception handling—when certain error conditions occur during instruction execution, the CPU stops normal execution and transfers control to an exception handler. Division by zero triggers a divide error exception. Invalid opcodes (trying to execute data as instructions) trigger invalid instruction exceptions. Page faults occur when accessing memory that isn’t currently in physical RAM. General protection faults result from privilege violations or memory access violations. The operating system registers exception handlers with the CPU, and when exceptions occur, the OS handler executes to decide how to respond.

Memory protection mechanisms prevent processes from accessing memory they shouldn’t. The Memory Management Unit (MMU) enforces protection by checking every memory access against page table permissions. Attempts to access memory belonging to other processes, to write to read-only pages, or to access kernel memory from user mode trigger protection faults. This hardware-level protection ensures memory isolation between processes and between user space and kernel space, preventing one program’s bugs from corrupting another program’s data or crashing the entire system.

System call validation catches errors when applications request operating system services. When an application makes a system call, the kernel validates parameters—checking that pointers point to valid user-space memory, that buffer sizes are reasonable, that file descriptors are valid, and that the process has necessary permissions. Invalid parameters cause system calls to fail with appropriate error codes rather than allowing operations that would corrupt kernel data structures or violate security.

Assertion checking involves programmers placing assertions—runtime checks that specific conditions are true—throughout code. In debug builds, failed assertions halt execution immediately at the point where invariants are violated, making bugs easier to locate. In production systems, assertions might be disabled for performance or might trigger error logging without halting. Assertions help catch logic errors early before they cause more serious problems later.

Watchdog timers detect hung processes or deadlocked systems. A watchdog is a timer that must be periodically reset by software to prevent triggering. If software hangs and stops resetting the watchdog, the timer expires and triggers a recovery action—killing the hung process, restarting a service, or even forcing a system reboot. Watchdogs are particularly common in embedded systems and server environments where reliability is critical.

Error-correcting code (ECC) memory detects and sometimes corrects memory errors. ECC memory stores additional bits alongside data that allow single-bit errors to be corrected and double-bit errors to be detected. When the memory controller reads data, it verifies the ECC bits and corrects single-bit errors transparently. Multi-bit errors that cannot be corrected trigger machine check exceptions, allowing the operating system to respond (often by killing the process using corrupted memory to prevent spreading corruption).

File system consistency checking detects corruption in file system metadata. Journaling file systems maintain transaction logs that enable recovery after crashes. File system checkers (fsck on Unix, chkdsk on Windows) scan file system structures looking for inconsistencies—orphaned blocks, incorrect link counts, cross-linked files—and attempt repairs. Modern file systems like ZFS and Btrfs use checksums on data and metadata to detect corruption from hardware errors or bugs.

Process monitoring detects application failures. Operating systems track process state, and when a process exits with non-zero status or is terminated by a signal/exception, the OS knows the process failed. Service managers restart crashed services automatically. Desktop environments display crash reporters when graphical applications crash.

How Operating Systems Respond to Errors

When errors are detected, operating systems implement various response strategies depending on error type and severity.

Graceful degradation allows systems to continue operating with reduced functionality when components fail. If a network interface fails, the system might switch to a backup interface. If memory errors are detected in a specific RAM region, the OS can mark that memory as bad and avoid using it. If a non-critical service crashes, the system restarts just that service rather than rebooting entirely. This approach maximizes availability—the system remains operational even when not everything works perfectly.

Process termination isolates application errors. When an application causes a memory access violation, attempts an illegal instruction, or encounters an unhandled exception, the operating system terminates that process rather than allowing the error to propagate. Unix systems send signals like SIGSEGV (segmentation fault), SIGILL (illegal instruction), or SIGFPE (floating-point exception), which default to process termination unless the application has installed signal handlers. Windows generates exceptions like EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION or EXCEPTION_ILLEGAL_INSTRUCTION, which terminate the process if unhandled. This containment prevents one application’s bugs from affecting other applications or the system.

Error code propagation returns error indicators from failed operations to calling code. System calls that fail return error codes (negative values or special return values) and set error variables (errno on Unix, GetLastError on Windows) indicating the specific failure reason. Library functions return error codes or use exception mechanisms. This allows applications to detect failures and respond appropriately—retrying operations, displaying error messages to users, or taking alternative approaches.

Exception handling mechanisms allow applications to catch and respond to errors. Languages like C++, Java, and Python support try-catch blocks where code that might fail executes in a try block, and catch blocks handle specific exception types. Operating systems support structured exception handling (SEH on Windows) that allows applications to install exception handlers. When hardware exceptions or software errors occur, the OS searches for exception handlers and invokes them, allowing applications to recover from errors, perform cleanup operations, or report failures gracefully rather than simply crashing.

Logging and reporting preserves information about errors for later analysis. When errors occur, operating systems write details to log files—system logs on Unix-like systems, Event Logs on Windows. Application crashes might trigger automatic crash reporting that collects crash dumps, system information, and sends reports to developers. Error logging serves multiple purposes: diagnosing problems (administrators can review logs to understand what went wrong), tracking trends (repeated errors indicate systemic problems), and forensic analysis (understanding the sequence of events leading to failures).

Kernel panic or system halt is the last resort for unrecoverable errors. When the kernel detects corruption of critical data structures, encounters bugs in kernel code paths where recovery is impossible, or receives fatal hardware errors, it executes a controlled halt. Modern kernels typically write crash dump information to disk, display error information on screen, and halt the system. This protects data integrity—continuing operation when the kernel is corrupted could cause data loss or file system corruption, so halting is safer than proceeding.

Automatic restart and recovery mechanisms minimize downtime. After kernel panics or critical failures, the system can automatically reboot. Service managers restart crashed services automatically based on configured policies. Systemd on Linux and Windows Service Control Manager can restart failed services after delays, with exponential backoff for services that repeatedly fail. Application-level recovery might include automatic save of work in progress, reopening documents after crashes, or restoring session state.

Crash Dump Generation and Analysis

When serious errors occur, capturing detailed system state information enables diagnosing and fixing the underlying causes.

Crash dumps are files containing snapshots of memory and processor state when crashes occur. These dumps preserve information that would otherwise be lost when the system or application terminates, allowing post-mortem debugging—analyzing crashes after they happen to understand what went wrong. Crash dumps are essential for diagnosing bugs that occur only in production environments, intermittent problems difficult to reproduce in testing, or issues that manifest only under specific conditions.

Windows crash dumps come in several varieties. Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) or kernel-mode crash dumps capture the state when Windows itself crashes. Complete memory dumps contain all physical RAM contents—gigabytes or tens of gigabytes of data. Kernel memory dumps contain only kernel memory (system memory), omitting user process memory to reduce dump size. Minidumps contain minimal information—just enough to identify the crash location and key parameters—typically a few hundred kilobytes. Windows generates dumps in %SystemRoot%\MEMORY.DMP or %SystemRoot%\Minidump\ depending on configuration. User-mode crash dumps for application crashes use Windows Error Reporting (WER), which can generate minidumps when applications crash.

Linux kernel crash dumps require special configuration. kdump is the standard Linux crash dump mechanism, using kexec to boot a secondary kernel when the primary kernel crashes. This secondary kernel runs with minimal functionality, writes a dump of the crashed kernel’s memory to disk, and reboots. crash dump files (typically in /var/crash/) can be analyzed with crash analysis tools. Core dumps for application crashes are generated automatically (if enabled with ulimit -c unlimited), writing the crashing process’s memory to a core file in the current directory or configured core pattern location.

macOS generates crash reports rather than full dumps. When applications crash, macOS creates crash reports in ~/Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports/ (for user applications) or /Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports/ (for system processes). These reports contain crash time, exception type, stack traces, loaded libraries, and other diagnostic information. For kernel panics, macOS writes panic information to NVRAM and displays it on the next boot, also creating panic reports in /Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports/.

Crash dump contents typically include processor registers (showing exactly what the CPU was doing when the crash occurred), stack contents (allowing reconstruction of the function call chain leading to the crash), memory contents (revealing variable values and data structure state), loaded module information (which DLLs or shared libraries were loaded), and thread states (in multithreaded applications, what each thread was doing). This information allows debuggers to examine crashed programs as if they were paused at the moment of failure.

Debugging symbols make crash dumps much more useful. Compiled programs convert human-readable source code into machine code, losing information about variable names, function names, and source code lines. Debug symbols preserve this mapping, allowing debuggers to display meaningful function names instead of raw addresses and to show which source code line corresponds to crash locations. Symbols are typically distributed separately from production binaries (in .pdb files on Windows, separate debug info on Linux) to keep binary sizes manageable while making debugging possible.

Crash dump analysis uses specialized tools. Windows Debugging Tools (WinDbg) analyzes Windows crash dumps, displaying stack traces, examining memory, and identifying crashing modules. On Linux, the crash utility analyzes kernel dumps, and gdb (GNU Debugger) analyzes core dumps. These tools allow stepping through code, examining variables, and understanding crash context. Automatic analysis can identify common crash patterns—null pointer dereferences, buffer overflows, stack corruption—and suggest likely causes.

Privacy and security considerations affect crash dumps. Dumps contain memory contents, potentially including sensitive data—passwords, encryption keys, personal information, or proprietary data. Organizations must balance the diagnostic value of crash dumps against privacy and security risks. Some systems sanitize dumps, redacting sensitive data before sending to vendors or uploading to crash reporting services. Users should be aware that crash dumps might contain sensitive information and handle them appropriately.

Error Reporting Systems

Modern operating systems include sophisticated error reporting infrastructure that collects crash information and helps improve software quality.

Windows Error Reporting (WER) automatically collects crash information when applications or Windows itself crashes. When a crash occurs, WER can display a dialog offering to send crash information to Microsoft. If the user consents, WER uploads a minidump and application information to Microsoft’s servers. Microsoft analyzes crash data, groups similar crashes together, and provides feedback to users if fixes are available. Application developers can access aggregated crash data for their applications through the Windows Dev Center, seeing which crashes affect the most users and prioritizing fixes accordingly. WER has significantly improved Windows stability by enabling data-driven bug fixing.

Apple Crash Reporter collects crash information on macOS and iOS. When applications crash, the system generates crash reports and offers to send them to Apple. For third-party applications, crash reports can be forwarded to application developers if they’ve registered for crash reporting access. App Store applications include App Analytics that shows crash rates and crash reports. This system has helped improve macOS and iOS application quality by making crash data accessible to developers.

Linux systems lack a standardized system-wide crash reporting mechanism, but various distributions implement their own solutions. Ubuntu uses Apport, which intercepts crashes, collects crash information including package versions and system details, and can automatically submit bug reports to Launchpad. Fedora uses ABRT (Automatic Bug Reporting Tool) that detects crashes, collects dumps and logs, and can submit reports to Red Hat’s bug tracker or the system administrator. These tools make crash reporting more accessible to end users who might not know how to file effective bug reports.

Application-specific crash reporting allows developers to receive crash information directly. Tools like Sentry, Raygun, or Bugsnag integrate into applications and automatically capture and transmit crash information when failures occur. Cloud-based crash reporting services aggregate crashes, identify trends, and alert developers to new issues. Mobile applications frequently include crash reporting SDKs (Firebase Crashlytics, Flurry Analytics) that provide detailed crash analytics.

Crash report contents typically include exception type and message, stack traces showing the call chain leading to the crash, operating system version and build number, application version and build information, CPU architecture, memory usage and available memory, locale and language settings, and time of crash. Some systems also collect loaded library versions, recently active features, and sanitized usage patterns. This comprehensive information helps developers reproduce and fix bugs.

Privacy in crash reporting is increasingly emphasized. Modern systems ask for user consent before uploading crash data, allow users to review crash reports before submission, explain how data will be used, and often anonymize data to protect user privacy. GDPR and similar regulations require careful handling of crash data that might contain personal information.

System Recovery and Restart Procedures

When crashes or errors occur, operating systems implement recovery procedures to restore functionality with minimal data loss and downtime.

Automatic process restart for services ensures critical services continue running despite crashes. Windows Service Control Manager monitors services and can automatically restart failed services after configured delays, with limits on restart attempts to prevent restart loops for persistently failing services. Linux systemd supports sophisticated restart policies through Restart= directives (always, on-failure, on-abnormal, etc.) and RestartSec= for restart delays. This automatic recovery means services like web servers, databases, or networking daemons recover from transient failures without manual intervention.

Application auto-save and recovery features minimize data loss when applications crash. Modern word processors, spreadsheets, and other productivity applications automatically save work in progress at regular intervals. When reopened after a crash, they detect unfinished work and offer recovery options. Web browsers restore tabs and session state after crashes. These recovery features significantly reduce the impact of application crashes on users.

System state restoration after kernel crashes involves automatic reboot. Most modern systems can be configured to automatically reboot after kernel panics or fatal system errors rather than halting indefinitely. Boot loaders might maintain multiple kernel versions, allowing automatic fallback to a previous kernel if the current one repeatedly fails to boot. This enables servers to recover from kernel crashes without administrator intervention.

Safe mode and recovery boot options provide degraded but functional systems for troubleshooting. Windows Safe Mode loads minimal drivers and services, allowing administrators to diagnose problems, remove problematic software, or restore configurations. Linux single-user mode provides a root shell with minimal services for system repair. macOS Recovery Mode boots a minimal system for disk repair, reinstallation, or restoration from backup.

File system recovery repairs corruption caused by crashes or hardware failures. Journaling file systems replay logged transactions during boot to restore consistency after unclean shutdown. File system checkers scan and repair structural inconsistencies. Modern copy-on-write file systems like ZFS and Btrfs maintain redundancy and checksums that enable automatic correction of many corruption types without data loss.

Checkpoint and rollback mechanisms allow reverting to known-good states. System Restore on Windows creates snapshots of system files and registry that can be restored if changes cause problems. Snapshot-capable file systems (ZFS, Btrfs, APFS) allow reverting entire file systems to previous points in time. Virtual machine snapshots capture complete system state for instant rollback. These mechanisms provide insurance against changes that break systems.

Last Known Good Configuration (historical Windows feature) allowed booting with the registry and drivers from the last successful boot, useful when recent changes prevented normal booting. Windows 10/11 replaced this with advanced startup options and automatic repair features that detect boot failures and attempt fixes.

Automatic Startup Repair in Windows detects repeated boot failures and automatically enters recovery mode, attempting fixes like restoring registry backups, repairing file system corruption, or disabling recently installed drivers. This reduces the need for manual recovery procedures for common boot problems.

Error Handling in Different Operating Systems

While error handling principles are universal, different operating systems implement specific mechanisms and adopt different philosophies.

Windows error handling emphasizes structured exception handling (SEH) that unifies hardware exceptions and software exceptions under a common framework. Applications can install exception handlers using __try/__except blocks, allowing fine-grained error recovery. Windows generates detailed exception codes identifying specific error types. The Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) appears for kernel-mode crashes, displaying a stop code, brief description, and driver information. Modern Windows includes Memory Dump analysis, Windows Error Reporting integration, and automatic restart after critical errors. Windows emphasis is on user experience—providing informative error messages, offering recovery options, and minimizing visible crashes through containerization and application isolation.

Linux error handling philosophy emphasizes transparency and returning errors rather than hiding them. System calls return error codes, and errno provides detailed error reasons. Kernel panics (oops on Linux) print detailed register dumps, stack traces, and debugging information to the console and logs, providing maximum information for troubleshooting. Linux makes less attempt to “protect” users from error details, instead providing comprehensive diagnostic information that knowledgeable administrators can use. Kdump and crash utilities enable thorough crash analysis. Linux’s open-source nature means crash dumps and error messages are essential for community-based debugging and fixing.

macOS combines Unix-like error handling with Apple’s user experience focus. Kernel panics display multilingual “You need to restart your computer” messages rather than technical details, but comprehensive panic logs are saved for later analysis. Application crashes show friendly error dialogs offering to reopen the application and report the crash to Apple, abstracting technical details from users while still collecting diagnostic information. macOS emphasizes graceful degradation—applications crash instead of the entire system, and rapid automatic restart minimizes user disruption.

Android uses Linux kernel error handling but adds application-level protections. Each application runs in its own process with strict sandboxing, so application crashes can’t affect other applications or the system. When applications become unresponsive, Android displays “Application Not Responding” (ANR) dialogs allowing users to force-close hung applications. System crashes can trigger automatic reboots on mobile devices, with Google collecting crash information through Play Services for analysis.

Embedded and real-time operating systems often emphasize failsafe behaviors and fault tolerance. Watchdog timers force resets if systems hang. Critical systems might run redundant processes and vote on results, detecting and isolating faulty components. Error handling is deterministic and predictable since missed deadlines or incorrect behaviors can have serious real-world consequences in industrial control, medical devices, or automotive systems.

Preventing Errors and Improving Reliability

Beyond handling errors when they occur, operating systems and applications implement practices to prevent errors and improve overall reliability.

Memory safety mechanisms prevent entire classes of errors. Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) randomizes memory locations of system libraries and executables, making exploitation harder. Data Execution Prevention (DEP) or No Execute (NX) bits mark memory regions as non-executable, preventing code injection attacks. Stack canaries detect buffer overflow attempts by placing guard values on the stack. Bounds checking verifies array accesses are within allocated memory. Modern languages like Rust enforce memory safety at compile time, preventing many memory-related crashes.

Input validation prevents errors from malformed or malicious input. Operating systems validate system call parameters before using them. Applications should validate all external input—user input, file contents, network data—before processing. Fuzzing tools automatically test applications with malformed input to discover crashes and vulnerabilities before deployment.

Resource limits prevent resource exhaustion. Operating systems enforce limits on process memory usage, CPU time, file sizes, number of open files, and other resources. When limits are reached, operations fail gracefully with appropriate errors rather than causing system-wide problems. Cgroups on Linux and Job Objects on Windows provide fine-grained resource control.

Defensive programming practices reduce bugs. Checking return values from all function calls catches errors immediately. Using assertions to verify preconditions and invariants catches logic errors early. Initializing variables prevents use of undefined values. Avoiding unsafe functions (strcpy, gets) prevents buffer overflows. Code review, static analysis, and comprehensive testing reduce bugs before deployment.

Redundancy and replication improve reliability in critical systems. RAID arrays tolerate disk failures. Redundant power supplies prevent single power supply failures from causing downtime. Application clustering and load balancing allow individual server failures without service interruption. Database replication ensures data survives hardware failures. These redundancy mechanisms are implemented at operating system, hardware, or application levels depending on requirements.

Graceful degradation design ensures systems provide reduced functionality when components fail rather than complete failure. Multi-tier applications might serve cached content if databases fail. Systems might operate without optional features when those subsystems crash. This resilience improves user experience and availability.

Conclusion

Error handling and crash recovery represent critical operating system responsibilities that determine system reliability, data integrity, and user experience. From detecting hardware exceptions and memory access violations to generating comprehensive crash dumps and automatically restarting failed services, modern operating systems employ sophisticated mechanisms to identify errors, contain damage, preserve diagnostic information, and restore functionality. The evolution from early systems where any error could crash the entire computer to modern architectures where application crashes are isolated and recoverable reflects decades of operating system development focused on reliability and robustness.

Understanding how operating systems handle errors—the types of errors they encounter, the detection mechanisms they employ, the crash dump information they preserve, the automatic recovery procedures they implement, and the error reporting systems that help improve software quality—provides essential knowledge for anyone working with computers professionally. System administrators troubleshooting server crashes, developers debugging application failures, or users recovering from system errors all benefit from understanding the error handling infrastructure working behind the scenes. The difference between a frustrating computing experience full of data loss and mysterious failures and a reliable experience where problems are quickly diagnosed and resolved often comes down to effective error handling and comprehensive crash reporting.

As computing continues evolving with more complex distributed systems, higher user expectations for reliability, and increasingly critical dependence on computer systems for essential services, error handling becomes ever more important. Modern systems must handle not just single-computer failures but cascading failures across distributed systems, must provide detailed diagnostic information while protecting user privacy, and must balance automatic recovery against preventing damage propagation. The fundamental principles remain constant—detect errors quickly, contain their impact, preserve information for analysis, and restore functionality—but the sophistication and comprehensiveness of error handling mechanisms continue advancing, making our computers more reliable, our work safer from data loss, and our systems easier to maintain and debug when inevitable problems occur.

Summary Table: Error Handling Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | Linux | macOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Crash Name | Blue Screen of Death (BSOD), STOP error | Kernel panic, oops | Kernel panic |

| Kernel Crash Display | Blue screen with stop code, technical details, QR code (recent versions) | Text dump of registers, stack trace to console/logs | Multilingual “restart required” message in multiple languages |

| Kernel Crash Dump | MEMORY.DMP (complete, kernel, or mini) in %SystemRoot% | kdump to /var/crash/ (if configured) | Panic log saved to NVRAM, /Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports/ |

| Application Crash Dump | WER minidumps in %LOCALAPPDATA%\CrashDumps\ or %TEMP% | Core dumps (core or core.PID) in working directory if enabled | Crash reports in ~/Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports/ |

| Crash Reporting Service | Windows Error Reporting (WER) | Apport (Ubuntu), ABRT (Fedora), varies by distro | Apple Crash Reporter |

| User Crash Dialog | “Application has stopped responding” with restart/close options | Varies by desktop environment (GNOME/KDE have crash reporters) | “Application quit unexpectedly” with reopen/report options |

| Error Logging | Event Viewer (Application, System, Security logs) | syslog, journalctl (systemd journal), /var/log/* | Console.app, unified logging (log show) |

| Exception Mechanism | Structured Exception Handling (SEH), __try/__except | Signals (SIGSEGV, SIGILL, SIGFPE, etc.) | BSD signals, Mach exceptions |

| Memory Protection | Virtual memory with DEP/NX, ASLR | MMU-enforced page protections, ASLR, NX bit | Virtual memory protection, ASLR, NX bit |

| Safe Mode | Safe Mode (F8 or shift-restart), minimal drivers/services | Single-user mode, rescue mode (from GRUB) | Recovery Mode (Command-R at boot) |

| Automatic Restart | Configurable in System Properties (restart after BSOD) | Systemd service restart policies, init scripts | launchd KeepAlive, automatic app restart |

| Crash Dump Analysis Tools | WinDbg, Visual Studio debugger | crash, gdb, addr2line | lldb, Xcode Instruments |

| Debug Symbols Format | .pdb (Program Database) files | DWARF debug info, separate debug packages | dSYM bundles |

| Service Recovery | Service Control Manager recovery actions (restart, reboot, run program) | systemd Restart= directives | launchd KeepAlive and exit timeout |

| Error Codes | NTSTATUS codes, Win32 error codes, HRESULT | errno values (POSIX standard) | errno values (POSIX standard) |

Common Error Types and OS Responses:

| Error Type | Windows Response | Linux Response | Typical Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Pointer Access | EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION, application terminates | SIGSEGV, process terminates (core dump if enabled) | Programming bug, uninitialized pointer |

| Stack Overflow | EXCEPTION_STACK_OVERFLOW, application terminates | SIGSEGV, process terminates | Infinite recursion, excessive stack allocation |

| Division by Zero | EXCEPTION_INT_DIVIDE_BY_ZERO, application terminates | SIGFPE, process terminates | Arithmetic error, missing validation |

| Out of Memory | ERROR_NOT_ENOUGH_MEMORY, operation fails, possibly invoke OOM killer | ENOMEM, OOM killer may terminate processes | Memory exhaustion, memory leak |

| Invalid Instruction | EXCEPTION_ILLEGAL_INSTRUCTION, application terminates | SIGILL, process terminates | Corrupted binary, CPU incompatibility, exploit attempt |

| Page Fault (valid) | Transparent page loading from disk, execution continues | Transparent page loading, execution continues | Demand paging, normal virtual memory |

| Page Fault (invalid) | EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION, application terminates | SIGSEGV, process terminates | Invalid pointer, buffer overflow |

| Kernel Panic | BSOD, create dump, halt or restart | Kernel panic, create dump (if kdump), halt or restart | Kernel bug, hardware failure, corrupted kernel data |

| Service Crash | Service Control Manager restarts (if configured) | systemd restarts (if Restart= configured) | Service bug, dependency failure |

| Disk Read Error | ERROR_READ_FAULT, I/O fails, logged | EIO error, I/O fails, logged | Hardware failure, bad sector |