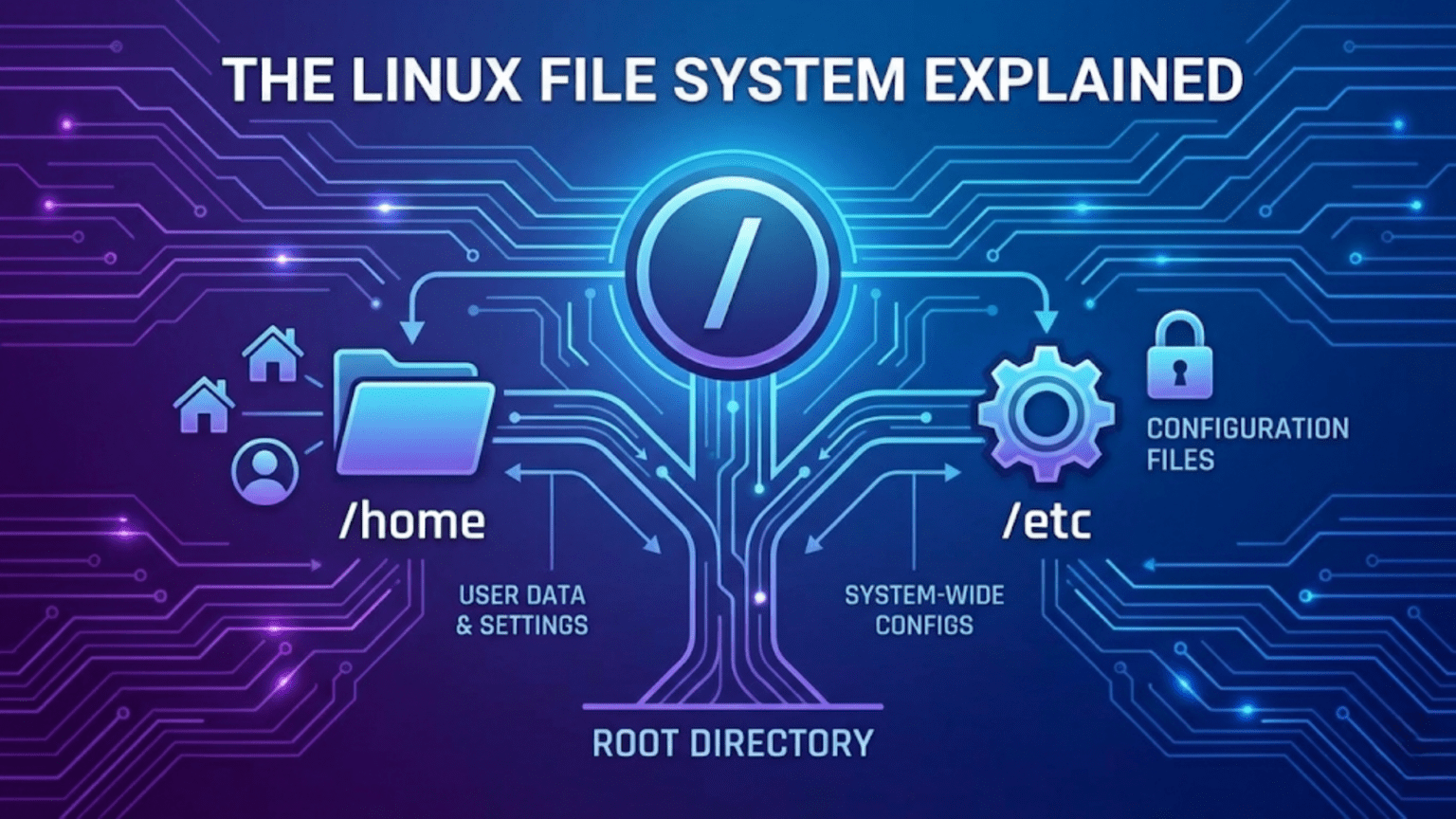

The Linux file system is organized as a single unified tree starting from the root directory, represented by a forward slash (/). Every file and directory on a Linux system — whether on your internal drive, a USB stick, or a network share — exists somewhere within this tree. Key directories include /home (personal user files), /etc (system configuration files), /var (variable data like logs), /usr (installed programs), and /tmp (temporary files). Unlike Windows, Linux uses no drive letters — everything is accessed through a unified path starting from /.

Introduction: A Map of Your Linux System

One of the first things that strikes people coming to Linux from Windows is how differently the file system is organized. In Windows, you have drive letters: C: for the main drive, D: for a DVD drive or second hard drive, E: for a USB stick. Each drive is its own separate tree of folders. In Linux, none of this exists. There are no drive letters. There is one single tree, starting from a single root, and everything — every file, every folder, every connected drive, every network share — exists somewhere within that one unified structure.

This design can feel disorienting at first. Where are your files? Where are programs installed? Why is there a folder called /etc and another called /var? What does /usr mean and why does it not just say “programs”? These questions are natural, and answering them thoroughly is the purpose of this article.

Understanding the Linux file system layout is not just academic. It is practical knowledge that makes you a more effective Linux user every single day. When you need to find a configuration file, you will know to look in /etc. When you wonder where a program was installed, you will know to check /usr. When disk space runs low, you will know which directories are most likely to contain large files. When you troubleshoot a system problem, you will know which log files to examine and where they live.

This article takes you through the Linux directory structure systematically — explaining what each major directory contains, why it exists, and how you will interact with it as a Linux user. By the end, the Linux file system will not be a mystery but a logical map you can navigate confidently.

The Fundamental Concept: One Tree, One Root

The Linux file system’s organizing principle is elegantly simple: there is exactly one root, and everything else branches from it.

The Root Directory: /

The forward slash character / has two meanings in Linux file paths, and understanding both is important. When it appears at the very beginning of a path — as in /home/sarah/documents — it represents the root directory: the top of the entire file system tree, the single ancestor of every other directory and file on the system. When it appears between path components — as in the slashes between home, sarah, and documents in that example — it is a separator, the Linux equivalent of the backslash in Windows paths.

The root directory itself contains no ordinary files. It contains only other directories — the top-level branches of the file system tree. Everything else in the system is reachable by starting at / and following a path of directories.

Absolute vs. Relative Paths

A path that begins with / is called an absolute path — it specifies a location starting from the root of the file system, unambiguously identifying one exact location regardless of where you currently are. /home/sarah/documents/report.txt is an absolute path that means: start at root, go into home, then into sarah, then into documents, and find the file report.txt.

A path that does not begin with / is a relative path — it specifies a location relative to your current working directory. If you are currently in /home/sarah, then documents/report.txt is a relative path pointing to the same file as /home/sarah/documents/report.txt. Relative paths are useful for brevity when working in the terminal, while absolute paths are unambiguous and reliable in scripts and configuration files.

The Tilde Shortcut: ~

Linux uses the tilde character ~ as a shorthand for your home directory. If your username is sarah and your home directory is /home/sarah, then ~/documents means the same thing as /home/sarah/documents. This shortcut works in the terminal and in many configuration files. You will see it constantly in Linux documentation and command examples.

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

The layout of directories in a Linux system is not arbitrary. It follows a specification called the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), maintained by the Linux Foundation. The FHS defines where different types of files should be placed, creating consistency across Linux distributions so that software and administrators can find files in predictable locations regardless of which distribution they are using.

Not every distribution follows the FHS perfectly — some have made historical decisions that deviate in minor ways — but the standard represents the consensus of the Linux community about where things belong, and understanding it gives you a map that works across virtually all Linux systems.

The Major Directories Explained

Let us walk through each major top-level directory in the Linux file system, explaining what it contains and why it matters.

/ — Root

As already discussed, / is the root of everything. On a typical Linux system, running ls / (the list command applied to the root directory) reveals about fifteen to twenty subdirectories. These are the top-level branches of the system, each with a specific purpose defined by the FHS.

One important security note: the root directory and most of its subdirectories are owned by the root user (the system administrator account) and are not writable by ordinary users. This is intentional — it prevents regular users from accidentally or maliciously modifying critical system files. You will encounter “Permission denied” errors if you try to write to system directories without using sudo (the command for temporary administrator access, covered in a later article).

/home — Personal User Files

The /home directory is where you will spend most of your time as an ordinary Linux user. It contains a subdirectory for each user account on the system. If three people use a Linux computer with accounts for alice, bob, and carol, the /home directory contains /home/alice, /home/bob, and /home/carol.

Your personal home directory is your private space on the system. It contains your documents, downloads, photos, music, videos, desktop files, and — critically — your personal configuration files for all the applications you use. When you configure your web browser’s bookmarks, install a Firefox extension, or change your code editor’s color scheme, those settings are stored as hidden files and folders within your home directory.

The default subdirectories you will find in your home directory are Documents, Downloads, Music, Pictures, Videos, Desktop, and Templates. These are created automatically and are recognized by most applications as the standard locations for their respective file types. When Firefox asks where to save a downloaded file, it defaults to your Downloads folder. When a photo editing application asks where to save an image, it defaults to your Pictures folder.

Your home directory is typically the only part of the Linux file system where you have unrestricted read and write access. Everywhere else — the system directories — requires administrator (root) privileges to modify.

/root — The Root User’s Home

Notice that /root is different from /. The single slash / is the root of the entire file system. /root (read as “slash root”) is the home directory specifically for the root user — the system administrator account. Just as ordinary users have their home directories in /home/username, the root user has their home directory at /root.

You will rarely need to access /root as a regular user. Most Linux distributions configure the root account to be inaccessible for direct login, instead requiring you to use sudo to perform administrative tasks while logged in as your regular user. When you use sudo, you are temporarily borrowing root’s privileges without actually logging in as root.

/etc — System Configuration Files

/etc (pronounced “et-see” or sometimes spelled out as individual letters E-T-C) is one of the most important directories for system administrators and power users. It contains the configuration files for the operating system and all installed system-wide software.

The name /etc comes from early Unix history and originally meant “et cetera” — it was where miscellaneous system files were placed. Over time, its role became specifically focused on configuration, and today /etc stands effectively for “editable text configuration.”

Every major system service and many applications store their configuration in /etc. Some examples you may encounter:

/etc/.hosts contains a list of hostname-to-IP-address mappings for local network name resolution — a simple file you can edit to block websites or assign friendly names to local network devices.

/etc/.fstab (filesystem table) defines which partitions and drives are mounted at startup, at which mount points, and with what options. This file is consulted every time the system boots.

/etc/.network/ or /etc/.NetworkManager/ contain network configuration files.

/etc/.apt/sources.list (on Debian/Ubuntu systems) and /etc/.apt/sources.list.d/ define the software repositories from which packages can be installed.

/etc/.ssh/sshd_config is the configuration file for the SSH server, which controls secure remote access.

/etc/.passwd contains a list of all user accounts on the system (not passwords — despite the name, passwords are stored separately in /etc/.shadow).

/etc/.crontab and the /etc/.cron.d/ directory contain scheduled tasks that run automatically at specified times.

Most files in /etc are plain text, readable and editable with any text editor. Modifying system configuration in /etc always requires root privileges. When you make configuration changes by editing files in /etc through the terminal, you typically do so with sudo nano /etc/.filename or sudo vim /etc/.filename.

/var — Variable Data

/var (short for “variable”) contains files that change frequently during normal system operation — data that grows and shrinks, that is updated continuously, or that is generated dynamically.

The most important subdirectory for most users is /var/.log, which contains the system’s log files. Log files are records of events that have occurred on the system — applications starting and stopping, errors encountered, security events, system updates applied, and much more. When something goes wrong with your Linux system, /var/.log is the first place to look for clues.

Common log files you may examine include:

/var/.log/syslog or /var/.log/messages — the main system log containing messages from the kernel and system services.

/var/.log/auth.log — records authentication events including login attempts (successful and failed) and uses of sudo.

/var/.log/apt/history.log — on Debian/Ubuntu systems, a record of software installations, removals, and upgrades performed through APT.

/var/.log/kern.log — kernel messages, useful for diagnosing hardware issues.

Other notable subdirectories in /var include /var/.cache (temporary cached data from package managers and applications), /var/.lib (persistent application data that changes over time, like database files), /var/.spool (queued data awaiting processing, like print jobs or mail), and /var/.tmp (temporary files that persist across reboots, unlike /tmp).

On modern systemd-based systems, most log information is also available through the journald system journal (accessible via the journalctl command), which provides structured, indexed logs that can be queried flexibly. Traditional text log files in /var/log still exist alongside the journal on most distributions.

/usr — User Programs and Data

/usr (short for “Unix System Resources,” though historically it stood for “user”) is the largest directory on a typical Linux system and contains the majority of installed programs and their supporting data.

Despite the name containing “user,” /usr is not where your personal user files live — that is /home. Instead, /usr contains the programs that all users can run, the libraries those programs depend on, and supporting data files.

The key subdirectories within /usr are:

/usr/bin contains the executable programs (binaries) available to all users. When you type a command in the terminal like firefox, gimp, or python3, the system finds and runs the executable from /usr/bin. This is the most populated directory on most Linux systems, containing hundreds or thousands of command files.

/usr/sbin contains system administration binaries — programs intended for use by the system administrator (root) rather than regular users. Tools for managing disk partitions, configuring network interfaces, and other administrative tasks live here.

/usr/lib contains shared libraries — the code libraries that programs in /usr/bin and /usr/sbin depend on. Shared libraries are similar to DLL files in Windows: multiple programs can use the same library simultaneously, saving disk space and memory compared to each program including its own copy of the library code.

/usr/share contains architecture-independent data that programs use: documentation, icons, themes, fonts, locale data (translations for different languages), and many other supporting files. This is where you will find application icons used by the desktop, manual pages for commands, and application-specific data files.

/usr/local is a special subdirectory within /usr designed for software installed locally by the system administrator, outside the distribution’s package manager. If you compile and install a program from source code, the convention is to install it into /usr/local/bin, /usr/local/lib, etc., rather than into the main /usr directories. This keeps locally installed software separate from distribution-managed software, making system upgrades cleaner.

/bin and /sbin — Essential System Binaries

On older Linux systems and in traditional Unix, /bin and /sbin were distinct from /usr/bin and /usr/sbin. The /bin directory contained essential command-line tools needed during system startup (before /usr was mounted), while /sbin contained essential system administration tools. /usr/bin and /usr/sbin contained non-essential programs available only after full system startup.

On most modern Linux distributions (including Ubuntu 20.04 and later, Fedora, and Arch Linux), /bin and /sbin are now symbolic links that point to /usr/bin and /usr/sbin respectively. This means they are effectively the same directory — there is no longer a meaningful distinction. The merger was made possible by modern boot systems that mount /usr early enough that the distinction is no longer necessary.

If you list the contents of / and see that /bin is shown as a link rather than a real directory, this merged arrangement is the reason.

/lib — Essential System Libraries

Similar to the /bin and /sbin situation, /lib traditionally held essential shared libraries needed during system startup (before /usr was available). Modern distributions have typically merged /lib into /usr/lib, with /lib becoming a symbolic link. You may also see /lib64 on 64-bit systems, pointing to 64-bit versions of essential libraries.

/tmp — Temporary Files

/tmp is a temporary storage area used by programs to create files they need briefly and then discard. When applications need scratch space — a place to write intermediate results, unpack archives before processing, or store data during a session — they use /tmp.

The critical characteristic of /tmp is that its contents are not permanent. On most modern Linux systems, /tmp is implemented as a tmpfs — a filesystem that exists entirely in RAM (with overflow to swap). This makes it extremely fast for applications to read and write, but it means everything in /tmp is lost when the system reboots.

Users can also use /tmp as their own temporary workspace, but should never store files they need to keep — a reboot will erase them. The /var/tmp directory is the appropriate choice when temporary files need to survive reboots.

Because /tmp is writable by all users, it is used for inter-process communication and temporary coordination between programs. This also makes it a target for certain security vulnerabilities, which is why many systems mount /tmp with the noexec option, preventing programs stored in /tmp from being executed directly.

/dev — Device Files

/dev is one of the most conceptually fascinating directories in the Linux file system. It contains device files — special files that represent hardware devices. In Linux, the principle of “everything is a file” means that hardware devices are represented as files in the /dev directory, and programs can communicate with hardware by reading from and writing to these device files.

Your hard drive or SSD is represented as /dev/.sda (for the first SATA drive) or /dev/.nvme0n1 (for the first NVMe drive). Partitions on that drive appear as /dev/.sda1, /dev/.sda2, etc. Your first CD/DVD drive might be /dev/.sr0. Your terminal sessions are represented as /dev/.tty1, /dev/.tty2, etc.

Two special device files worth knowing are /dev/.null and /dev/.random. /dev/.null is a “black hole” — anything written to it is discarded, and reading from it returns nothing. It is useful in shell commands when you want to suppress output. /dev/.random and /dev/.urandom generate cryptographically random data and are used by security-sensitive applications for random number generation.

Most users never interact directly with /dev — the kernel and system services manage these device files automatically. But seeing /dev in a path in documentation or error messages tells you something is dealing with hardware or device-level access.

/proc — Process and Kernel Information

/proc is another virtual filesystem — its contents are not files on disk but dynamically generated by the kernel to expose information about running processes and kernel state. Reading a file in /proc gives you live system information; writing to certain files allows you to adjust kernel parameters.

Numbered directories in /proc correspond to running processes: /proc/.1234 contains information about the process with PID 1234. Within such a directory, files like cmdline show the command that started the process, status shows its current state and memory usage, and fd shows its open file descriptors.

The file /proc/.cpuinfo contains detailed information about your CPU. /proc/.meminfo shows current memory usage. /proc/.version shows the kernel version and build information. Many system monitoring tools read their data directly from /proc.

/sys — System and Hardware Information

/sys is similar to /proc in being a virtual filesystem, but it specifically exposes information about the hardware devices attached to the system and their drivers, organized according to the kernel’s device model. System configuration tools and desktop environments use /sys to get information about batteries, CPUs, network interfaces, and other hardware.

Like /proc, /sys is not a directory you will typically navigate manually, but understanding it exists explains why commands like cat /sys/class/power_supply/BAT0/capacity can tell you your laptop’s battery percentage — they are reading directly from kernel-maintained virtual files.

/mnt and /media — Mount Points

When you connect a USB drive, insert an SD card, or attach an external hard drive to a Linux system, the device needs to be “mounted” — attached to a specific point in the file system tree so that its contents are accessible as part of the directory structure. The /mnt and /media directories exist as conventional locations for these mount points.

/media is used by modern desktop environments and the udisks system for automatically mounting removable media. When you plug in a USB drive and it appears in your file manager, it has been mounted under /media/username/drive-label. The full path to a file on that USB drive might be /media/sarah/MyDrive/photos/vacation.jpg.

/mnt is a traditional mount point used for manual mounting by system administrators. If you need to temporarily mount a network share, an additional hard drive, or a disk image, you would typically mount it somewhere under /mnt. Unlike /media which is managed automatically, /mnt is a conventional scratch space that administrators use as they see fit.

/opt — Optional Application Software

/opt (short for “optional”) is the conventional location for large, self-contained application packages that install outside the standard directory hierarchy. Applications installed in /opt typically place all their files — executables, libraries, configuration, data — in a single subdirectory, like /opt/google/chrome or /opt/slack.

This approach differs from the FHS-standard approach (where executables go in /usr/bin, libraries in /usr/lib, etc.) and is typically used by commercial software vendors who want to keep all their files together for easier management, as well as for software that is not available through the distribution’s package manager.

Common examples of software that installs in /opt include Google Chrome, Slack, many games, and some development tools. When you download a package directly from a vendor’s website and install it, it often goes into /opt.

/boot — Boot Loader and Kernel Files

/boot contains the files needed to start the system — the Linux kernel itself, the initial RAM disk (initrd or initramfs) used during early startup, and the GRUB bootloader configuration.

The kernel file is typically named something like vmlinuz-6.8.0-35-generic (the name varies by kernel version and distribution). The initramfs (initial RAM filesystem) is a compressed archive that the kernel unpacks into memory during early startup, providing the drivers and tools needed to mount the real root filesystem.

Regular users rarely need to interact with /boot directly. The package manager handles kernel updates automatically, placing new kernel files in /boot and updating GRUB’s configuration to include the new kernel as a boot option. However, if you manually compile and install a custom kernel, you will place the resulting files in /boot.

One practical consideration: /boot is sometimes on a separate partition with limited size. If you have an older system with a small /boot partition, running out of space in /boot can prevent kernel updates from succeeding. The fix is to remove old, unused kernel versions to free space.

Understanding the Full Directory Tree at a Glance

The following table summarizes every major top-level directory, its purpose, and typical interaction level for everyday users:

| Directory | Full Name/Meaning | Contains | User Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| / | Root | Everything — the top of the tree | Navigate through it, rarely touch directly |

| /home | Home | Personal user directories and files | Daily — all your personal files live here |

| /root | Root user home | Home directory for the root account | Rarely — only when doing admin work |

| /etc | Editable Text Config | System-wide configuration files | Occasionally — when configuring services |

| /var | Variable data | Logs, caches, databases, spool files | Occasionally — check logs for troubleshooting |

| /usr | Unix System Resources | Installed programs, libraries, shared data | Rarely directly — managed by package manager |

| /bin | Binaries (→ /usr/bin) | Essential user commands | Indirectly — these are the commands you run |

| /sbin | System binaries (→ /usr/sbin) | Essential admin commands | Rarely — system tools accessed via sudo |

| /lib | Libraries (→ /usr/lib) | Essential shared libraries | Never directly — managed by package manager |

| /tmp | Temporary | Short-lived temporary files | Occasionally — clear when disk is full |

| /dev | Devices | Device files for hardware | Rarely — when diagnosing hardware issues |

| /proc | Processes | Virtual kernel/process information | Occasionally — system info commands use it |

| /sys | System | Virtual hardware/driver information | Rarely — advanced hardware configuration |

| /mnt | Mount | Manual mount points | Occasionally — when mounting drives manually |

| /media | Media | Automatic mount points for removable media | When using USB drives and SD cards |

| /opt | Optional | Self-contained third-party applications | When using software installed outside package manager |

| /boot | Boot | Kernel, initramfs, bootloader files | Rarely — managed by package manager |

How This Differs from Windows

For users coming from Windows, the contrast with the Windows directory structure is striking and worth addressing directly.

Windows uses drive letters (C:, D:, E:) to represent separate storage volumes. Each drive is a separate tree. If you install a program on C: and have a data drive at D:, there is no built-in relationship between them — they are separate hierarchies.

Linux uses a single unified tree. Additional drives (internal drives, USB drives, SD cards, network shares) are “mounted” at specific points within the single tree. A second internal hard drive might be mounted at /data, making its contents accessible at /data/projects, /data/backups, etc. A USB drive might be mounted at /media/sarah/MyUSB. From the user’s perspective, there is one filesystem, and drives are simply folders within it.

This unified approach has practical advantages. You can move the physical location of data without changing any paths — if you mount a new, larger drive at /home, all user home directories seamlessly move to the new drive. You can create symlinks that transparently redirect access from one location to another. Backup and configuration tools can work with the entire filesystem through a single, consistent path system.

The equivalent of Windows’ Program Files in Linux is primarily /usr/bin (for executable commands) and /usr/lib (for program data and libraries), with /opt serving as a secondary location for self-contained applications. The equivalent of AppData (per-user application settings) is hidden dotfiles and dotdirectories within your home directory (~/.config, ~/.local/share, etc.).

Hidden Configuration Files in Your Home Directory

When you enable the display of hidden files in your file manager (Ctrl+H), your home directory reveals a second layer of content: configuration files and directories whose names begin with a dot. These are sometimes called dotfiles or dotdirectories.

The ~/.config directory is where most modern applications store their configuration, following a standard called the XDG Base Directory Specification. Your VS Code settings might be at ~/.config/.Code/User/settings.json. Your GNOME keyboard shortcuts are stored in ~/.config/.dconf. Application-specific configuration subdirectories accumulate here over time.

The ~/.local directory contains user-specific data and installed software. ~/.local/.share holds application data (music player databases, application icons, desktop files). ~/.local/.bin is where user-installed executables can be placed and will be found by the shell without administrator privileges.

The ~/.cache directory contains cached data — temporary files that applications generate to speed up future operations. Browser cache, thumbnail images generated by the file manager, and compilation caches all live here. If you are running low on disk space, ~/.cache is generally safe to clear (applications will regenerate their caches as needed, at the cost of a one-time slowdown).

Older applications and configuration traditions use dotfiles directly in the home directory: ~/.bash.rc (Bash shell configuration), ~/.pro.file (login shell configuration), ~/.git.config (Git configuration), ~/.s.sh/ (SSH keys and configuration). As Linux matures, new applications increasingly prefer ~/.config/.appname/ over home-directory dotfiles, but both patterns remain common.

Navigating the File System in Practice

Understanding the directory structure becomes second nature when you start exploring it, both through the graphical file manager and through the terminal.

In the File Manager

Your graphical file manager gives you a visual way to explore the directory structure. By default, most file managers open to your home directory (/home/username). The sidebar shows bookmarks to common locations within your home directory.

To navigate to system directories, you need to explicitly navigate to the root. In Nautilus (GNOME’s file manager), press Ctrl+L to reveal the location bar and type / then Enter to go to the root. In Nemo (Mint’s file manager) and Dolphin (KDE’s file manager), the location bar is always visible — click it and type the path you want. In Thunar (XFCE), use the Go menu or the location bar.

Exploring /usr, /etc, and /var through the file manager is an excellent way to build familiarity with the directory structure visually. You can see the files, open plain-text configuration files to read them, and understand what the system is organizing.

In the Terminal

The terminal provides the most direct way to navigate the file system. Three commands are fundamental:

pwd (print working directory) tells you your current location in the file system — your “current directory.” Running it immediately after opening a terminal typically shows /home/username, confirming you start in your home directory.

ls (list) shows the contents of your current directory or any directory you specify. ls /etc lists the contents of the /etc directory. ls -la (with the -l for long format and -a for all files including hidden) shows detailed information about every file including hidden dotfiles.

cd (change directory) moves you to a different directory. cd /etc moves to /etc. cd ~ or just cd with no argument returns to your home directory. cd .. moves up one level (to the parent directory). cd - returns to the previous directory you were in — handy for switching between two locations.

Combining these three commands lets you navigate the entire file system from the terminal, examining its contents as you go.

Why the Linux File System Structure Makes Sense

After learning the purpose of each directory, it becomes clear that the Linux file system structure embodies a coherent design philosophy rather than growing organically without thought.

The separation of user files (/home) from system files (/usr, /etc) means that reinstalling or upgrading the operating system does not affect personal data if /home is on a separate partition. System administrators routinely reinstall Linux while preserving /home, giving users a fresh system without losing any of their files or personal configuration.

The separation of configuration (/etc) from programs (/usr/bin) means that updating a program does not overwrite its configuration. When you install a newer version of a server application through the package manager, your carefully crafted configuration in /etc survives intact.

The temporary directories (/tmp, /var/cache) provide performance benefits by giving programs fast storage for data that does not need to persist — on systems where /tmp is tmpfs (in RAM), writing temporary files is dramatically faster than writing to disk.

The device file abstraction (/dev) allows the same programs to work with different hardware through a consistent interface — a program that reads from /dev/sda works whether /dev/sda is a spinning hard drive, an SSD, or a USB stick, because the kernel presents them all through the same abstracted interface.

This thoughtful separation of concerns — user data, system configuration, programs, libraries, temporary storage, devices, logs — is one of the hallmarks of good system design, inherited from Unix’s decades of evolution and refined by the Linux community.

Conclusion: The Map You Will Use Every Day

The Linux file system is not arbitrary or confusing once its logic becomes clear. It is a carefully organized structure that separates different types of data by their purpose, their permanence, and their access requirements. Your personal files in /home are yours alone and survive system changes. Configuration in /etc controls how the system behaves. Programs in /usr/bin are what you run. Logs in /var/log tell you what happened. Devices in /dev are the hardware layer made accessible.

As a Linux user, you will interact primarily with /home — browsing your documents, downloading files, organizing your photos. You will occasionally venture into /etc to configure a service or /var/log to diagnose a problem. You will rarely need to touch /usr or /dev directly, because the package manager and kernel handle those for you.

But knowing the whole map — understanding what every directory is for and why it exists — transforms you from a passive user into someone who understands the system they are using. That understanding is what separates the Linux user who is occasionally confused by unexpected behavior from the one who can look at an error message, recognize a path in it, and immediately understand which part of the system the error relates to.

The Linux file system is your system’s map. Now that you understand it, you can navigate anywhere on that map with confidence.