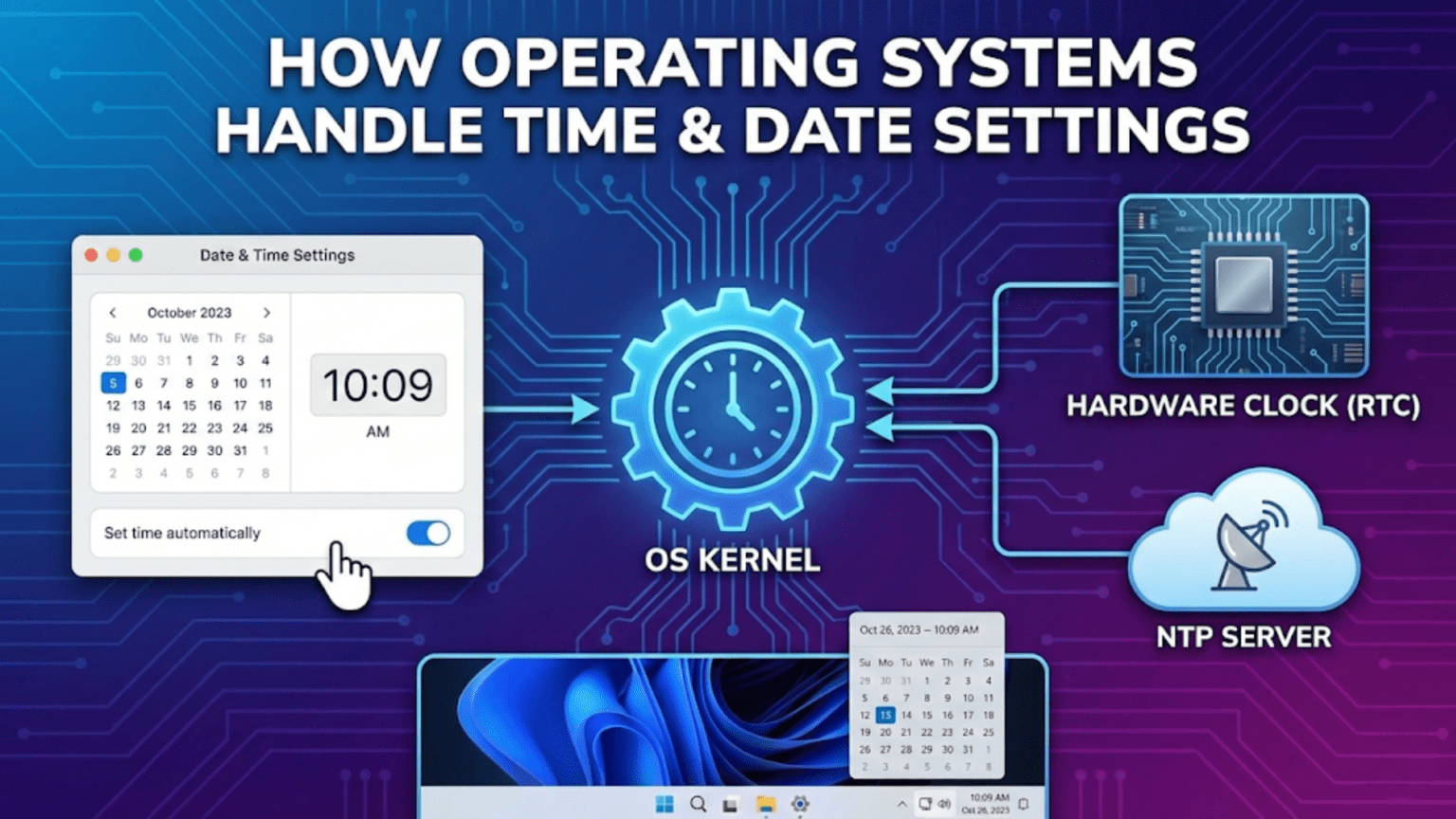

Operating systems manage time and date through a combination of hardware clocks that maintain time when powered off, software clocks that track time while the system runs, time synchronization protocols like NTP that correct clock drift by comparing with authoritative network time servers, and time zone databases that convert universal time to local time. Together these mechanisms ensure accurate, consistent time across reboots, across networks, and across geographical locations.

Time seems like something computers should handle trivially—clocks are simple, time is continuous, and computers are good at counting. Yet accurate timekeeping in operating systems is surprisingly complex, touching hardware design, distributed systems theory, network protocols, cultural geography, and even political history. Your computer’s clock involves at least two distinct hardware mechanisms, software layers that smooth over hardware imprecision, network protocols that coordinate time across millions of machines to within milliseconds, a database encoding decades of time zone history, and careful handling of edge cases like daylight saving transitions, leap seconds, and the difference between how computers store time and how humans experience it. When you schedule a video call across time zones, timestamp a file, synchronize data across devices, or run a distributed database, accurate time management is essential infrastructure that the operating system provides invisibly.

The stakes for time accuracy are higher than most users realize. Distributed systems depend on timestamps for ordering events and resolving conflicts—databases use time to determine which write happened last, security certificates have validity periods enforced by checking current time, software licenses expire at specific times, log files use timestamps to reconstruct event sequences during incident investigations, and authentication protocols reject requests with timestamps more than a few minutes off as potential replay attacks. A computer with a significantly wrong clock can fail SSL certificate validation (preventing HTTPS connections), fail authentication to network services, corrupt file timestamps used for backup decisions, or cause mysterious failures in distributed applications. Operating systems invest substantial effort in maintaining accurate time precisely because so much depends on it. This comprehensive guide explores how operating systems manage timekeeping hardware, synchronize time over networks, handle time zones and daylight saving, address the special challenges of distributed time, and expose time services to applications.

Hardware Time: The Two Clocks

Modern computers rely on two separate hardware clocks that serve complementary roles in timekeeping.

The Real-Time Clock (RTC) is a dedicated, battery-powered hardware chip on the motherboard that maintains the date and time even when the computer is powered off. The RTC runs continuously on its own small battery (typically a CR2032 coin cell), ticking forward even when your computer is unplugged and sitting in a closet. When you turn on your computer, the operating system reads the current time from the RTC to initialize the system clock. Without the RTC battery (which eventually dies after 5-10 years), computers forget the time when powered off, requiring manual time entry on each boot—a situation familiar to users of very old computers or those who replace their motherboard battery.

RTC accuracy is limited. Cheap quartz oscillators used in RTCs drift by seconds to minutes per month. The RTC in your computer might gain or lose 10-20 seconds per week without correction. This drift is tolerable for knowing roughly what time it is, but inadequate for applications requiring precise timestamps or synchronization. RTC drift accumulates over time, so a computer without network time synchronization gradually diverges from actual time, eventually showing significantly wrong times.

The system clock (or software clock, processor clock for timekeeping) is an in-memory counter maintained by the operating system during normal operation. Unlike the RTC, the system clock is volatile—it’s lost when the computer powers off—so it must be initialized from the RTC at each boot. Once initialized, the system clock is updated by hardware timer interrupts at regular intervals. Modern systems use high-resolution performance counters (like the Time Stamp Counter on x86 processors, which increments at processor frequency) for fine-grained time measurement, while maintaining the current time-of-day through periodic timer interrupts.

System clock resolution varies by platform. Older Windows systems had 15.6ms timer resolution (64 interrupts per second). Modern Windows defaults to 15.6ms but can be reduced to 0.5ms by applications requesting high resolution. Linux typically uses 1ms or 4ms resolution. macOS provides high-resolution timing through Mach kernel APIs. Higher resolution is valuable for precise timing but increases CPU overhead from more frequent timer interrupts.

The relationship between RTC and system clock involves synchronization at boot and potentially during operation. At startup, the OS reads the RTC and sets the system clock. During operation, NTP (Network Time Protocol) adjustments update the system clock but may or may not update the RTC depending on configuration. When shutting down, some operating systems write the current system clock value back to the RTC to preserve any NTP corrections. The next boot starts with the NTP-corrected time rather than the original drifted RTC time.

Hardware clock UTC vs. local time represents an important configuration choice. The RTC can store either UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) or local time. Linux conventionally stores UTC in the RTC, while Windows historically stored local time (matching what users expect to see). This difference creates complications on dual-boot systems—if Windows writes local time to the RTC but Linux reads it as UTC, one system will have the wrong time. Modern Linux systems can be configured to use local time in the RTC (matching Windows), and Windows can be configured via registry to use UTC, enabling correct dual-boot behavior.

Network Time Synchronization

Network Time Protocol (NTP) synchronizes computer clocks over networks, correcting drift and maintaining accuracy to within milliseconds of universal time.

NTP operates in a hierarchical structure called a stratum. Stratum 0 devices are primary reference clocks—atomic clocks, GPS receivers, radio clocks—that provide highly accurate time. Stratum 1 servers connect directly to stratum 0 devices and provide time to stratum 2 servers, which serve stratum 3 servers, and so on up to stratum 15. Each stratum level adds slight additional uncertainty. Public NTP pools like pool.ntp.org aggregate hundreds of volunteer stratum 1 and 2 servers, providing reliable time to any internet-connected computer.

NTP algorithm compensates for network latency when synchronizing. Since network packets take time to travel (network latency), simply reading the time from an NTP server would show a time in the past—the time when the server prepared its response. NTP measures round-trip time by comparing message send and receive timestamps, estimates one-way latency as half the round-trip time, and adjusts the received timestamp accordingly. This compensation provides sub-millisecond accuracy over local networks and typically millisecond-level accuracy over the internet.

Clock discipline is NTP’s approach to applying time corrections without disrupting time continuity. Rather than abruptly jumping the clock to the correct time (which could confuse applications relying on monotonic time progression), NTP uses slewing—gradually speeding up or slowing down the clock by adjusting its rate until it converges to the correct time. A clock running fast might be slowed by 0.01% until synchronized; a clock running slow might be sped up. This gentle correction keeps time monotonically increasing without disrupting applications.

Large time errors trigger step corrections. If the clock is more than 128ms off (the NTP panic threshold), slewing alone would take too long—at 500ppm (maximum slew rate), correcting a 1-second error takes 33 minutes. NTP steps the clock immediately for large errors, then switches to slewing for fine-tuning. Some NTP implementations refuse to step the clock at all once synchronized, requiring extreme errors (indicating possible attack or hardware malfunction) to be corrected manually.

NTPv4 (RFC 5905) is the current NTP version, providing improved security and accuracy over earlier versions. SNTP (Simple NTP) is a simplified subset suitable for clients that don’t need the full NTP implementation—many embedded devices and some desktop systems use SNTP. Windows Time Service uses its own proprietary protocol with NTP compatibility. PTP (Precision Time Protocol, IEEE 1588) provides sub-microsecond accuracy for specialized high-precision applications, used in financial trading systems, telecommunications, and scientific instruments.

The Windows Time Service (W32tm) implements NTP client and server functionality. On domain-joined computers, the domain controller hierarchy provides time, ensuring all domain computers are synchronized together—crucial for Kerberos authentication which rejects requests with timestamps more than 5 minutes off. Standalone Windows computers synchronize with time.windows.com. The w32tm command-line tool queries NTP status, forces synchronization, and diagnoses time synchronization problems.

Linux NTP clients include the traditional ntpd (NTP daemon) and the modern Chrony. Chrony is designed for intermittently connected computers and environments where the time might jump significantly—it handles these cases better than ntpd and synchronizes faster after network reconnection. systemd-timesyncd is a simpler NTP client built into systemd, suitable for basic time synchronization needs without the complexity of full ntpd or Chrony. timedatectl is the systemd command for managing time configuration, showing current time, NTP sync status, and time zone.

macOS uses timed (the time daemon) backed by Apple’s own time servers (time.apple.com) for NTP synchronization. The Time & Date preferences pane provides configuration, and the sntp command enables command-line time queries. Apple Silicon Macs have additional precision timing infrastructure supporting new use cases requiring precise coordination.

Time Zones and UTC

Time zones convert between the universal reference of UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) and the local times people use, a conversion complicated by political boundaries, daylight saving time, and historical changes.

UTC is the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. UTC replaced GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) as the primary standard in 1972, though UTC and GMT differ by less than a second (GMT is astronomical, UTC is atomic). All time zones are defined as offsets from UTC—Eastern Standard Time is UTC-5, Japan Standard Time is UTC+9, India Standard Time is UTC+5:30 (note the non-integer offset). Most computers store and process time internally as UTC, converting to local time only for display.

The tz data.base (also called zoneinfo or Olson database after its creator Arthur David Olson) is the authoritative database of time zone rules used by nearly every operating system. The tz database encodes not just current time zone rules but the complete history of every time zone—every rule change, DST transition, and political boundary shift since time zones were standardized. This historical accuracy is essential for correctly interpreting timestamps from the past: files created in New York in 1965 must be interpreted with the DST rules that applied in 1965, not today’s rules.

Time zone identifiers in the tz database use a hierarchical naming scheme: America/New_York, Europe/London, Asia/Tokyo, Pacific/Auckland. These identifiers are more precise than abbreviations like EST or PST, which are ambiguous (EST is used by both US Eastern Standard Time and Australian Eastern Standard Time) and not standardized. Applications should use full tz database identifiers for unambiguous time zone specification.

Daylight Saving Time (DST) transitions cause the most time-related programming and user experience problems. Twice per year (in regions observing DST), clocks spring forward (losing an hour) or fall back (repeating an hour). The transition rules vary by country—the US transitions at 2 AM on specific Sundays in March and November, while European countries transition at 1 AM UTC on the last Sundays of March and October. Countries and regions change their DST rules periodically, requiring tz data.base updates. Operating systems receive tz data.base updates through normal system updates.

The “fall back” transition creates a genuinely ambiguous hour. At 2 AM when clocks fall back to 1 AM, the hour from 1 AM to 2 AM occurs twice. A local time of 1:30 AM could be either the first occurrence (standard time) or the second (daylight saving time). Operating systems handle this ambiguity by specifying whether a local time is in standard or DST mode, but converting between local time and UTC during this ambiguous hour requires knowing which occurrence is meant.

The “spring forward” transition creates a gap—the hour from 2 AM to 3 AM never occurs. Any time in that range (2:15 AM, 2:45 AM) is invalid. Scheduling events for times in that gap causes problems, and applications must handle the possibility that a computed local time might fall in a non-existent range.

Windows stores time zone information in the Windows Registry under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Time Zones, with separate keys for each time zone containing display names, UTC offset, and DST rules in Windows-specific format. Windows time zones map roughly (but not exactly) to tz database zones, with some differences in historical accuracy and granularity.

IANA tz database updates are distributed through Linux/macOS package managers (tzdata or equivalent package), through Windows Update, through iOS/Android system updates, and through programming language runtimes. When a country changes its time zone rules, updated tz databases must reach all affected systems before the change takes effect—tz database updates are time-critical in a literal sense.

Monotonic Time and Clock Sources

Beyond wall clock time, operating systems provide monotonic clocks for measuring elapsed time without being affected by clock adjustments.

Wall clock time (the actual date and time) can jump forward or backward due to NTP corrections, DST transitions, manual adjustments, or virtualization. These jumps make wall clock time unsuitable for measuring durations—if you start timing an operation at 1:59 AM and DST ends, moving the clock back to 1:59 AM, your elapsed time calculation would show a negative duration or a spuriously long one.

Monotonic clocks provide time that only moves forward, regardless of wall clock adjustments. Monotonic time is suitable for measuring elapsed time, timeouts, and performance benchmarking. CLOCK_MONOTONIC on Linux and macOS provides this guarantee. GetTickCount and QueryPerformanceCounter on Windows are similarly monotonic. The caveat: monotonic clocks are meaningless across system reboots (their epoch is undefined) and generally shouldn’t be synchronized between different machines.

CLOCK_MONOTONIC_RAW (Linux) provides monotonic time uncorrected by NTP adjustments—useful for extremely accurate performance measurements where even the slight slewing adjustments of NTP would distort timing. CLOCK_REALTIME is the POSIX wall clock (can jump), while CLOCK_MONOTONIC is guaranteed to never go backwards but may be adjusted by NTP slewing.

The vDSO (virtual Dynamic Shared Object) mechanism on Linux allows reading CLOCK_REALTIME and CLOCK_MONOTONIC from userspace without system calls, by mapping current timekeeping state into each process’s address space. This makes frequent time queries (common in applications like web servers that timestamp every request) essentially free in terms of system call overhead.

High-resolution timers provide sub-millisecond timing for performance measurement and precise scheduling. HPET (High Precision Event Timer) and TSC (Time Stamp Counter) on x86 systems provide nanosecond resolution. TSC increments at processor frequency but must be used carefully—it can vary across processor cores (on older CPUs without invariant TSC), pauses during sleep states, and has different starting points across cores. Modern processors with invariant TSC address most of these issues.

Time in Distributed and Virtualized Systems

Distributed systems and virtual machines present special challenges for time management that go beyond single-machine considerations.

Distributed system time consistency is crucial for correctness. When multiple machines coordinate on a task, ordering events correctly requires that timestamps from different machines be comparable. If Machine A’s clock is 100ms ahead of Machine B’s, an event at 12:00:00.100 on A appears to have happened before an event at 12:00:00.150 on B, when in reality A’s event happened after B’s if clocks were synchronized. Protocols like Paxos and Raft that coordinate distributed systems are carefully designed to work correctly despite clock skew, but application-level reasoning about event ordering requires clock synchronization.

Google’s TrueTime API, used in Google Spanner (a globally distributed database), takes a unique approach by acknowledging clock uncertainty explicitly. Rather than pretending clocks are perfectly synchronized, TrueTime provides time as a confidence interval [earliest, latest] guaranteed to contain the true time. Transactions must wait until their uncertainty window resolves before committing, ensuring global ordering at the cost of latency proportional to clock uncertainty (a few milliseconds with GPS-disciplined clocks).

Virtual machine time management is particularly challenging. When a VM is paused, suspended, or migrated to a different host, the VM’s clock can drift significantly—pausing a VM for 10 minutes then resuming it would show a 10-minute gap in clock time if nothing compensated. Hypervisors and virtualization platforms implement guest clock synchronization: VMware Tools, VirtualBox Guest Additions, Hyper-V Integration Services, and KVM’s virtio-pvsync all synchronize the guest VM’s clock with the host’s, correcting for time spent paused or migrated.

Containers share the host kernel’s time, meaning container clocks cannot be independently set. A container always shows the same time as its host—there’s no per-container clock. This is generally desirable (containers need accurate time for the same reasons physical machines do), but it means containerized applications cannot override the system clock without host-level access.

Leap seconds are periodic one-second adjustments to UTC that keep atomic time aligned with Earth’s rotation. Since Earth’s rotation is gradually slowing, UTC must periodically add leap seconds (23 have been added since 1972). Leap seconds cause the sequence 23:59:59 → 23:59:60 → 00:00:00, with the 61st second being the leap second. This breaks many assumptions in software. POSIX time (Unix time) traditionally ignores leap seconds, representing them as a duplicate of the preceding second. “Leap smearing” distributes the leap second over many hours, gradually adjusting time to avoid the discontinuity—used by Google, Amazon, and other large-scale systems.

Time Display and User Experience

Converting stored UTC time to user-visible local time involves multiple formatting and localization considerations.

Locale-aware time formatting presents time in formats appropriate for different cultures and languages. The US uses 12-hour time with AM/PM (2:30 PM), while most of the world uses 24-hour time (14:30). Date formats differ dramatically—MM/DD/YYYY is standard in the US, DD/MM/YYYY in most of Europe, and YYYY-MM-DD (ISO 8601) internationally. Month and day names require translation. Operating systems provide locale-aware formatting APIs (strftime on Unix, DateTimeFormatter in Java, Intl.DateTimeFormat in JavaScript) that handle these variations automatically based on locale settings.

ISO 8601 format (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS±HH:MM) provides an unambiguous international standard for date-time representation, used for data interchange between systems. Including timezone offset (like +05:30 for IST or Z for UTC) makes the timestamp unambiguous regardless of where it’s parsed.

Time zone display in user interfaces requires balancing precision and clarity. Showing “UTC-5” is precise but unfamiliar to most users. Showing “Eastern Time” is familiar but ambiguous (EST vs EDT). Many applications show both the offset and the name. The tz database name (America/New_York) is unambiguous but unfamiliar to users. Applications must balance technical precision against user-friendly presentation.

Relative time display (“5 minutes ago,” “yesterday,” “2 weeks ago”) is often more useful for recent events than absolute timestamps. Applications like email clients, social media, and file managers show relative times for recent items and absolute dates for older ones. This display requires accurate knowledge of current time and careful handling of time zones when displaying times to users in different zones.

Time and date pickers in user interfaces must handle DST edge cases, especially for scheduling applications. A meeting scheduled for “2:30 AM on the DST fall-back day” is ambiguous without specifying first or second occurrence. Calendar applications should handle and communicate this ambiguity rather than silently choosing one interpretation.

Operating System Time Management Tools

Every major operating system provides tools for viewing and configuring time settings.

Windows time management centers on Settings > Time & Language > Date & Time, providing options for automatic time zone detection, automatic time synchronization, manual time and date setting, and additional clock display (showing multiple time zones in the system tray clock). The w32tm command-line tool provides detailed control: “w32tm /query /status” shows synchronization status, “w32tm /resync” forces immediate synchronization, and “w32tm /config” modifies time service configuration. The Date and Time Control Panel applet provides access to Internet Time settings and additional clock displays.

Linux time management through systemd uses timedatectl as the primary management command. “timedatectl” shows current time, time zone, NTP synchronization status, and RTC time. “timedatectl set-timezone America/New_York” changes the time zone. “timedatectl set-ntp true/false” enables or disables NTP. “timedatectl set-time” sets time manually (only when NTP is disabled). The /etc/local.time symlink (pointing to a tz database file in /usr/share/zone.info/) or /etc/time.zone file stores the time zone setting.

macOS time management through System Settings > General > Date & Time provides automatic time zone setting (using location services), automatic time setting via Apple’s NTP servers, and manual override options. The date command in Terminal shows and sets time, while sntp provides NTP query functionality. The “Open Language & Region” button accesses locale settings affecting time display format.

Command-line time utilities provide scriptable access. The date command on Unix-like systems formats and displays current time (also sets time when run as root). “date +%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S%z” outputs ISO 8601 format. “hwclock” reads and writes the RTC. “ntpq” and “ntpstat” query NTP status. “chronyc” provides comprehensive Chrony status and control. These tools enable time management in scripts, monitoring systems, and automated administration.

Time Security

Time plays a critical role in security systems, making accurate timekeeping a security requirement rather than merely a convenience.

TLS/SSL certificate validation depends on current time. SSL certificates have notBefore and notAfter validity periods, and clients refuse connections to servers presenting expired certificates or certificates not yet valid. A computer with a wrong clock might reject valid certificates (if the clock is behind the certificate’s notBefore) or accept expired certificates (if the clock is ahead). Certificate validation failures due to wrong system time are a common frustration, and the error messages (“certificate not yet valid” or “certificate has expired”) can be cryptic when the real issue is an incorrect system clock.

Kerberos authentication, used in Windows Active Directory environments, requires clocks to be within 5 minutes of each other. This “skew tolerance” prevents replay attacks—capturing a Kerberos ticket and replaying it minutes or hours later—while accommodating small clock differences. A computer more than 5 minutes out of sync with the domain controller fails Kerberos authentication, preventing domain login and access to network resources. This requirement makes NTP synchronization mandatory in Active Directory environments.

TOTP (Time-based One-Time Password), used by authenticator apps like Google Authenticator and Authy, generates passwords based on current time. A phone with an incorrect clock generates wrong TOTP codes, causing authentication failures. Most TOTP implementations tolerate ±30 second skew (one time window in either direction), but larger errors cause failures. This is why “sync time” is recommended troubleshooting for authenticator apps generating invalid codes.

NTP security itself has been a concern. NTP amplification attacks use NTP servers to amplify DDoS attacks. NTPsec and Chrony implement authentication and security features addressing various NTP attack vectors. The leap second announcement mechanism in NTP has historically been a source of bugs that caused widespread server crashes when leap seconds occurred.

Conclusion

Time management in operating systems encompasses hardware clock maintenance, software clock precision, network synchronization protocols, time zone database management, distributed system coordination, and security-critical timekeeping—a far more complex domain than the simple concept of “what time is it” might suggest. The two-hardware-clock model (RTC for persistence, system clock for precision), NTP synchronization that keeps clocks accurate to milliseconds, the tz database encoding decades of political time zone history, monotonic clocks for duration measurement, and careful handling of DST ambiguities and leap seconds together form infrastructure that modern computing depends upon silently and continuously.

For everyday users, understanding OS time management means knowing how to troubleshoot time synchronization failures, why network time is important for security certificate validation, how time zone changes affect scheduled events, and why computers’ clocks drift without correction. For developers, time awareness informs proper use of UTC versus local time, monotonic versus wall clocks, tz database identifiers versus ambiguous abbreviations, and DST-safe scheduling. For system administrators, time management is critical infrastructure—NTP synchronization failures can disable authentication, corrupt log timestamps, and cause mysterious distributed system failures.

The invisible accuracy of your system clock, quietly synchronized to atomic time standards via NTP, correctly converting to your local time zone including DST, and providing timestamps to every application that needs them, represents one of the operating system’s many quietly essential services. When it works perfectly (which modern systems ensure almost always), you never think about it. When it fails, the failures can be frustratingly mysterious—the result of tight dependencies on accurate time throughout modern computing systems.

Summary Table: Time Management Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | macOS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTC Storage Default | Local time (configurable to UTC via registry) | UTC | UTC |

| NTP Client | Windows Time Service (W32Time) | timed (Apple’s daemon) | systemd-timesyncd, ntpd, or Chrony |

| Default NTP Servers | time.windows.com | time.apple.com | pool.ntp.org or distro-specific |

| NTP Management Command | w32tm | sntp, systemsetup | timedatectl, ntpq, chronyc |

| Time Zone Storage | Windows Registry (HKLM…Time Zones) | /etc/local.time symlink | /etc/local.time symlink or /etc/time.zone |

| Time Zone Database | Windows-proprietary (maps to IANA) | IANA tz data.base (/usr/sha.re/zoneinfo) | IANA tz data.base (/usr/sha.re/zoneinfo) |

| Domain Time Sync | AD domain controller hierarchy (Kerberos) | Open Directory / AD integration | sssd / AD integration with Chrony |

| GUI Configuration | Settings > Time & Language > Date & Time | System Settings > General > Date & Time | GNOME Settings / KDE System Settings |

| CLI Set Time | w32tm, net time, Set-Date (PowerShell) | date, systemsetup | date, timedatectl, hwclock |

| Monotonic Clock | GetTickCount64, QueryPerformanceCounter | CLOCK_MONOTONIC (POSIX) | CLOCK_MONOTONIC (POSIX) |

| High-Res Clock | QueryPerformanceCounter (100ns resolution) | mach_absolute_time (ns resolution) | clock_gettime CLOCK_REALTIME (ns) |

| vDSO Time Optimization | No equivalent | No equivalent | Yes (CLOCK_REALTIME, CLOCK_MONOTONIC) |

| Leap Second Handling | Windows smearing approach | Leap smearing | Configurable (ntpd/Chrony leapfile) |

| Auto Time Zone Detection | Location Services integration | Location Services integration | geoclue (optional) |

| Kerberos Skew Tolerance | 5 minutes (configurable via GPO) | 5 minutes | 5 minutes (configurable) |

Common Time-Related Problems and Solutions:

| Problem | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSL certificate errors | System clock significantly wrong | Check date/time in system settings | Enable NTP sync or set correct time manually |

| Kerberos auth failures (AD) | Clock >5 min off from domain controller | w32tm /qu.ery /status | Ensure NTP points to domain controller; check NTP sync |

| TOTP codes invalid | Authenticator device clock off | Check time on phone; compare to known-good source | Sync phone time; most apps have manual sync option |

| Scheduled tasks wrong time | Time zone misconfigured | Check time zone setting vs intended | Set correct time zone in OS settings |

| Files have wrong timestamps | RTC wrong before NTP sync | Check file creation times; check system log | Enable NTP, check RTC battery if persistent |

| Time correct but displaying wrong | Incorrect time zone setting | Compare UTC and local time; verify time zone | Change time zone to correct region |

| Dual-boot clock disagreement | Windows/Linux RTC convention mismatch | Check both OSes; note difference | Configure Windows to use UTC or Linux to use local time |

| Huge time jump after suspend | VM or sleep resume, no re-sync | Check NTP logs; observe time before/after sleep | Ensure guest tools installed (VM); configure NTP re-sync on resume |

| NTP not synchronizing | Firewall blocking UDP 123, NTP server unreachable | w32tm /qu.ery /status; ntpq -p | Open UDP port 123, verify server addresses, check network |