The Illusion of Simultaneous Execution

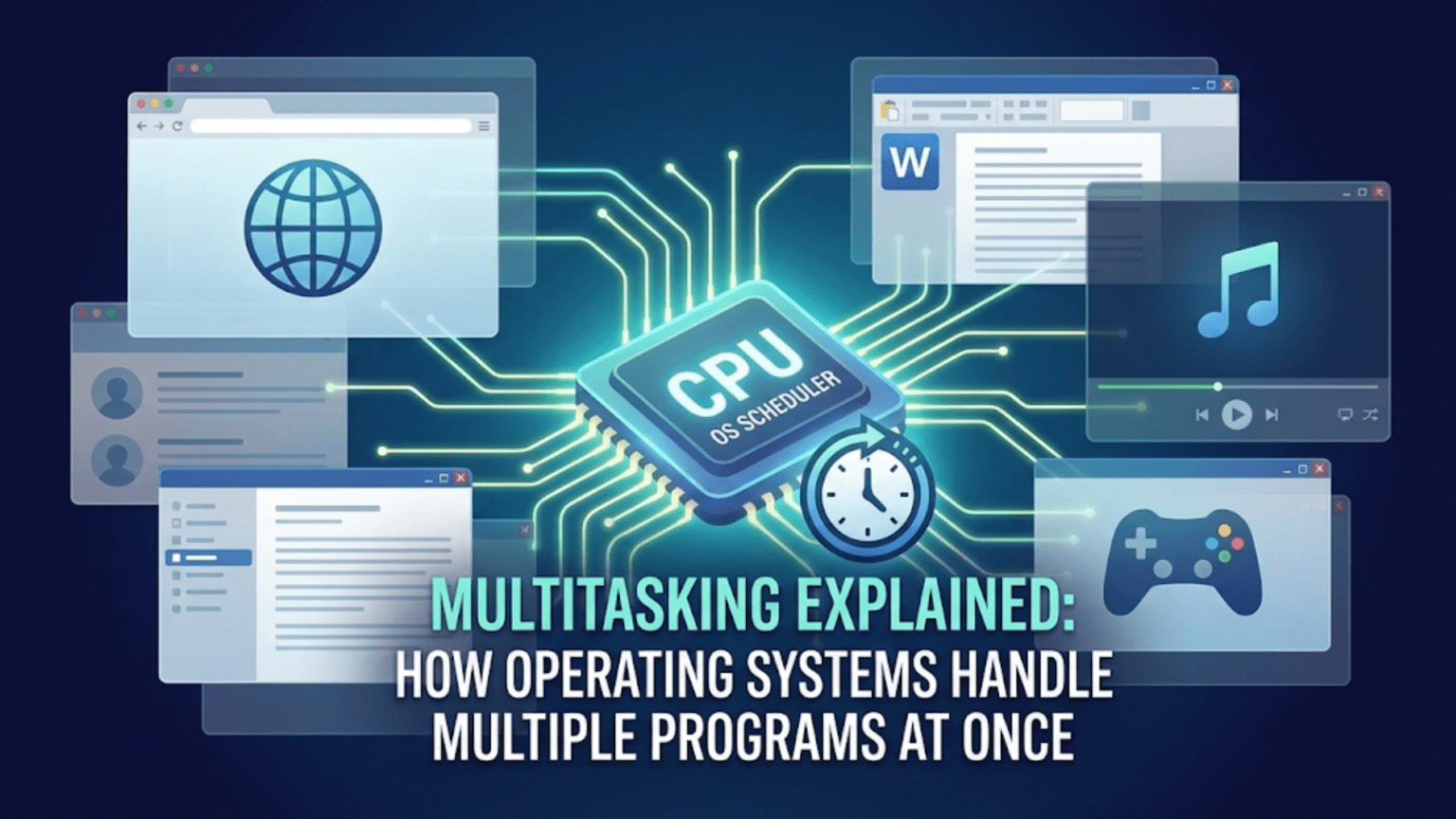

When you’re listening to music while browsing the web, editing a document with a video playing in the background, and receiving email notifications—all at the same time—you’re witnessing one of the operating system’s most impressive feats: multitasking. Your computer appears to run dozens or even hundreds of programs simultaneously, all responding to your input and completing their work without apparent interference. This seamless juggling act represents sophisticated engineering that has evolved over decades, transforming computers from single-task machines into the versatile platforms we depend on today.

The remarkable truth is that most of this simultaneous execution is an elaborate illusion. Unless your computer has as many processor cores as running programs—an unlikely scenario—the processor isn’t actually executing multiple programs at the same instant. Instead, the operating system rapidly switches between programs, giving each one a brief slice of processor time before moving to the next. This switching happens so quickly—thousands of times per second—that it creates the convincing appearance that everything runs at once. Understanding how operating systems orchestrate this performance reveals fundamental principles of computer architecture and helps explain why systems sometimes slow down, why certain programs seem more responsive than others, and how modern computers achieve such impressive capabilities.

Multitasking evolved from practical necessity. Early computers were enormously expensive, and having one sit idle while waiting for slow input/output operations or human interaction wasted valuable resources. Engineers developed time-sharing systems that allowed multiple users to work on the same computer simultaneously, with each user getting a portion of the machine’s attention. These pioneering systems established principles that modern operating systems still follow: isolate programs from each other, allocate resources fairly, prioritize interactive tasks, and create the illusion of dedicated access to the machine. Today’s personal computers implement these same concepts, providing you with a responsive, multi-program environment even when running on modest hardware.

Processes and Threads: The Basic Units of Execution

Before understanding how operating systems manage multitasking, we need to understand what they’re managing. The operating system doesn’t think in terms of “programs”—it works with more precise concepts called processes and threads.

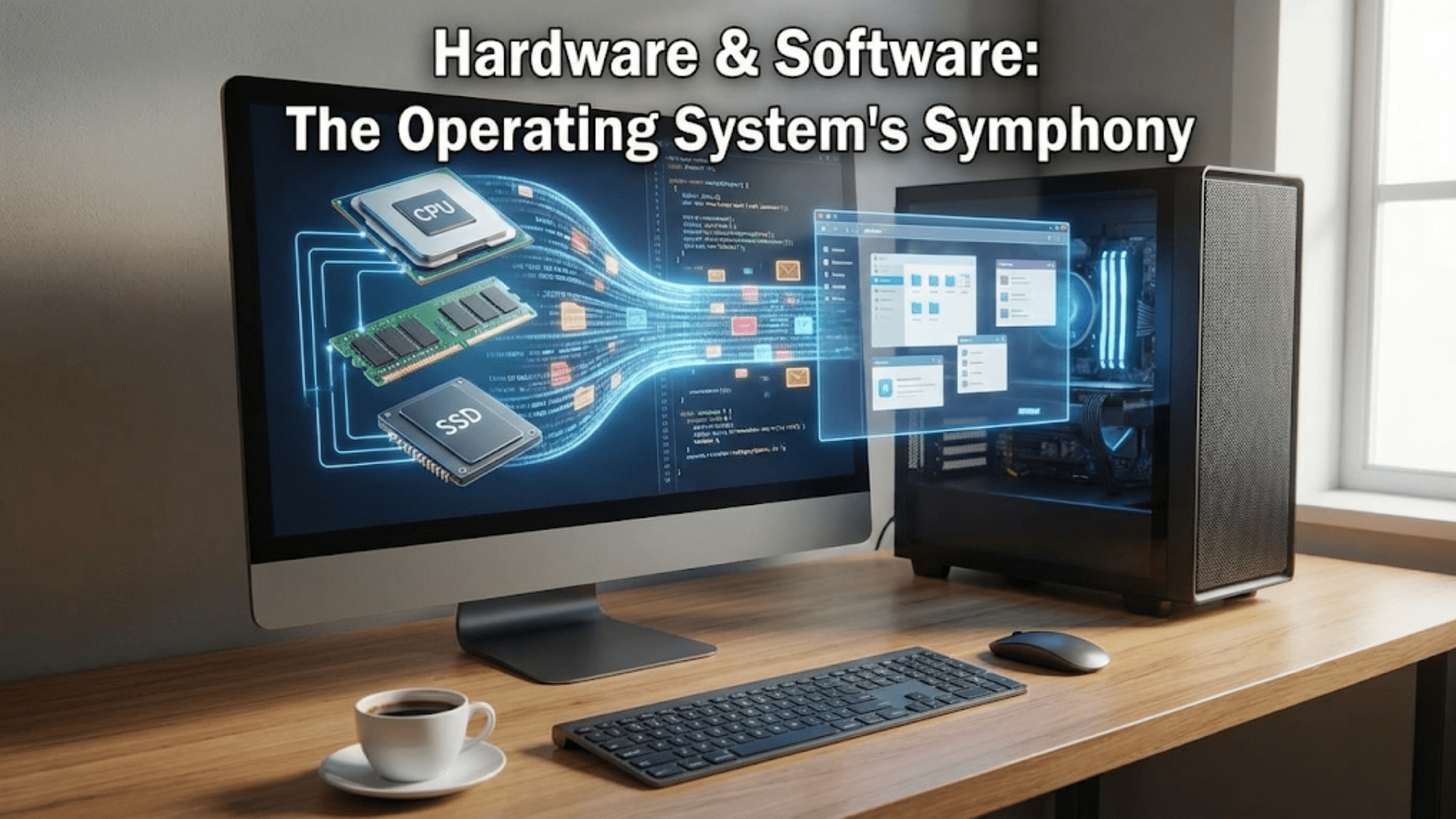

A process represents a running instance of a program. When you double-click an application icon, the operating system creates a process for that program. The process includes the program’s executable code loaded into memory, allocated memory for the program’s data, open files and network connections, security credentials identifying which user owns the process, and various other resources the program needs to run. Each process exists in its own isolated memory space, unable to directly access memory belonging to other processes. This isolation provides both security—preventing programs from interfering with each other—and stability—a crash in one process doesn’t bring down others.

Multiple processes can run from the same program. If you open three windows of your web browser, you might have three separate browser processes running simultaneously, each with its own memory space and resources. Modern browsers often use even more processes, isolating different tabs or components for security and stability. Each process operates independently, though they may communicate through inter-process communication mechanisms provided by the operating system.

Threads represent individual flows of execution within a process. While a process defines the boundaries and resources of a running program, threads are the actual sequences of instructions being executed. A simple program might have just one thread, executing instructions sequentially from start to finish. More sophisticated programs create multiple threads to perform different tasks concurrently. A video player might use one thread to read video data from disk, another to decode video frames, another to decode audio, and another to display the result. These threads share the process’s memory space and resources but can execute independently.

The relationship between processes and threads can be thought of as a business analogy. A process is like a company with its own office space, equipment, and resources. Threads are like employees working within that company. The employees share the office and equipment but can work on different tasks simultaneously. Just as employees in different companies can’t directly access each other’s offices, threads in different processes can’t directly access each other’s memory.

Creating processes is more expensive than creating threads because processes require their own isolated memory spaces and resource allocations. The operating system must set up page tables, allocate memory, duplicate file descriptors, and establish security contexts. Creating a thread within an existing process is much lighter weight—the memory space and most resources already exist, and the operating system just needs to set up the thread’s execution context. This difference makes threads attractive for programs that need concurrent execution without the overhead and isolation of separate processes.

The operating system maintains detailed information about each process and thread in data structures called process control blocks and thread control blocks. These structures store everything the OS needs to manage execution: the current execution state, memory allocations, priority, scheduling information, open resources, and much more. When the operating system switches between processes or threads, it saves the current state to these control blocks and loads the state for the next task to execute.

The Scheduler: Deciding Who Runs When

At the heart of multitasking lies the scheduler—the operating system component that decides which process or thread should execute at any given moment. With potentially hundreds of tasks competing for limited processor cores, the scheduler makes thousands of decisions per second, balancing competing goals: maximize overall throughput, keep interactive programs responsive, treat all processes fairly, and minimize the overhead of switching between tasks.

Schedulers use various algorithms to make these decisions, each with different characteristics and trade-offs. Understanding these algorithms reveals why operating systems behave the way they do and helps explain performance patterns you might observe.

First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) represents the simplest scheduling algorithm: execute processes in the order they arrive. Like a single-file queue at a store, whoever arrives first gets served first. This approach is easy to understand and implement, and it’s perfectly fair in one sense—no one cuts in line. However, FCFS has a significant problem: a long-running task blocks all subsequent tasks from executing, even if those tasks could complete quickly. Imagine waiting behind someone processing a thousand-item purchase when you just need to buy milk. Modern operating systems rarely use pure FCFS because of these responsiveness issues.

Round-robin scheduling gives each process a fixed time slice, called a quantum, typically measured in milliseconds. The scheduler maintains a queue of processes ready to run. It picks the first process, lets it execute for one quantum, then moves it to the end of the queue and picks the next process. This rotation continues indefinitely, ensuring every process gets regular processor time. Round-robin provides fairness and prevents any single process from monopolizing the processor. However, choosing the right quantum size matters: too short and the system spends excessive time switching between processes; too long and interactive responsiveness suffers.

Priority-based scheduling assigns each process a priority level, always selecting the highest-priority ready process to run. This allows the system to favor important processes over less critical ones. Interactive programs like text editors get high priority to maintain responsiveness, while background tasks like system maintenance get lower priority. However, naive priority scheduling can cause starvation—low-priority processes might never run if high-priority processes constantly exist. Operating systems address this through priority aging, gradually increasing a process’s priority the longer it waits, ensuring even low-priority processes eventually execute.

Multi-level feedback queues combine multiple approaches, using several queues with different priorities and time quantums. New processes start in the highest-priority queue with a short quantum. If a process uses its entire quantum, it drops to a lower-priority queue with a longer quantum. This naturally separates interactive processes that execute briefly before waiting for input from CPU-intensive processes that execute for long periods. Interactive processes stay in high-priority queues and respond quickly to user input, while CPU-bound processes drop to lower priorities but get longer uninterrupted execution when they do run. This algorithm automatically adapts to process behavior without requiring explicit priority specification.

Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), used by Linux, takes a different approach based on the concept of fairness. Rather than fixed time slices, CFS tracks how much processor time each process has received and schedules processes that have received the least time. It maintains a red-black tree data structure ordered by virtual runtime—the amount of time a process has executed, weighted by priority. The scheduler always picks the leftmost node in the tree, ensuring the process that’s received the least CPU time runs next. This approach provides excellent fairness and good responsiveness while adapting naturally to varying numbers of processes.

Real-time scheduling addresses applications with strict timing requirements, like industrial control systems or audio processing. Real-time schedulers guarantee that certain processes execute within specific time bounds, essential when missing a deadline causes system failure or unacceptable quality degradation. These schedulers use fixed priorities and preemption to ensure time-critical processes always run when needed. Most general-purpose operating systems provide soft real-time scheduling that aims for good timing but doesn’t guarantee hard deadlines, suitable for audio/video applications but not safety-critical systems.

Modern multi-core processors complicate scheduling significantly. With multiple cores executing simultaneously, the scheduler must decide not just which process runs but also which core runs it. Processor affinity—preferring to run processes on the same core they used previously—improves performance by keeping processor caches hot with relevant data. Load balancing ensures all cores stay busy rather than letting some sit idle while others are overloaded. Symmetric multiprocessing treats all cores equally, while NUMA-aware scheduling considers that some memory is closer (faster) to certain cores and schedules accordingly.

Context Switching: The Mechanics of Multitasking

When the scheduler decides to switch from one process or thread to another, the operating system performs a context switch—saving the current task’s state and loading the next task’s state. Understanding this operation reveals both the remarkable engineering that makes multitasking possible and the overhead costs that limit how rapidly switching can occur.

The processor’s state at any moment includes numerous components: the program counter indicating which instruction to execute next, register contents holding working data, processor flags indicating various conditions, memory management unit configuration defining virtual memory mappings, and floating-point unit state if applicable. All of this state must be preserved when switching away from a task and restored when switching back. Without perfect state preservation, tasks would see corrupted data, execute wrong instructions, or crash outright.

The context switch begins when the scheduler decides to switch tasks. This typically happens when the currently running task’s time quantum expires, when the task performs an operation that blocks (like waiting for disk I/O), when a higher-priority task becomes ready to run, or when the task voluntarily yields the processor. The scheduler issues an interrupt or system call that transfers control to the operating system kernel.

The kernel immediately saves the current task’s state. It copies all processor registers to the task’s thread control block in memory. It saves the program counter so execution can resume at exactly the right instruction. It records processor flags, floating-point state, and other architecture-specific state. For thread switches within the same process, this is all that’s necessary. For process switches, the kernel must also switch to the new process’s memory space by loading different page tables into the memory management unit—a relatively expensive operation that flushes caches and translation lookaside buffers.

After saving the old task’s state, the kernel loads the new task’s state from its control block. It restores registers, program counter, processor flags, and all other saved state. For process switches, it loads the new process’s page tables and updates security contexts. Once the state is fully restored, the kernel returns from the interrupt or system call, but now execution continues in the new task rather than the old one. From the new task’s perspective, it simply resumes executing wherever it left off, completely unaware that it was suspended while other tasks ran.

The overhead of context switching isn’t trivial. Each switch might take several microseconds—not much in human terms, but enough to matter when switches happen thousands of times per second. This overhead includes the direct cost of saving and restoring state, the indirect costs of cache invalidation and memory system disruption, and the scheduler overhead deciding which task to run next. Operating systems work to minimize this overhead while still providing good responsiveness and fairness.

Some clever optimizations reduce context switch costs. Lazy floating-point state saving delays saving floating-point registers until the new task actually uses them, avoiding the cost if the task doesn’t do floating-point math. Hardware support for virtualization allows some state to be saved and restored more efficiently. Fast system call mechanisms reduce the overhead of entering and leaving kernel mode. Despite these optimizations, context switching remains a fundamental cost of multitasking.

The frequency of context switches depends on the scheduler’s time quantum and how often tasks block waiting for I/O or other events. Systems running many interactive tasks might perform tens of thousands of context switches per second. CPU-intensive workloads with few tasks might switch far less frequently. You can observe context switch rates using system monitoring tools—high rates might indicate excessive multitasking overhead, while very low rates might suggest insufficient concurrency.

Synchronization and Race Conditions

When multiple processes or threads execute concurrently, they sometimes need to coordinate their activities or share data. This coordination creates complex challenges: how can threads safely access shared data without corruption? How can processes wait for events in other processes? How can resources be shared without conflicts? The operating system provides synchronization primitives that solve these problems, though using them correctly requires careful programming.

Race conditions occur when multiple threads access shared data simultaneously and the outcome depends on the exact timing of their execution. Imagine two threads both trying to increment a shared counter. Each thread reads the current value, adds one, and writes the result back. If thread A reads the value (say, 100), then thread B reads the same value (still 100) before thread A writes back, both threads write 101 and the counter increases by only one instead of two. The “race” between the threads causes incorrect results. Race conditions are pernicious bugs because they occur intermittently depending on timing, making them hard to reproduce and debug.

Mutual exclusion mechanisms prevent race conditions by ensuring only one thread at a time can access shared data. Locks (also called mutexes for “mutual exclusion”) provide basic mutual exclusion. A thread must acquire a lock before accessing protected data and release it when finished. Other threads attempting to acquire the lock while it’s held will block—suspend execution until the lock becomes available. This ensures that protected operations execute atomically—appearing to happen instantaneously without interruption—preventing interference between threads.

However, locks introduce new problems. Deadlock occurs when threads wait for each other in a cycle, preventing any from making progress. Thread A holds lock 1 and waits for lock 2, while thread B holds lock 2 and waits for lock 1—neither can proceed. Deadlocks require careful programming discipline to avoid: acquire locks in consistent order, avoid holding locks longer than necessary, and use timeout mechanisms to detect and recover from deadlocks. Operating systems provide detection mechanisms that identify deadlocked threads, though breaking deadlocks often requires human intervention.

Semaphores provide more flexible synchronization, useful for managing pools of resources or coordinating producer-consumer scenarios. A semaphore maintains a counter and two operations: wait (decrement the counter, blocking if it becomes negative) and signal (increment the counter, potentially waking waiting threads). Semaphores can model various synchronization patterns: binary semaphores act like locks, counting semaphores manage resource pools, and semaphores enable signaling between threads.

Condition variables allow threads to wait for specific conditions to become true. A thread can wait on a condition variable, blocking until another thread signals the condition. This avoids busy-waiting—repeatedly checking a condition in a loop—which wastes processor time. Combined with locks, condition variables enable efficient coordination: acquire the lock, check the condition, if not satisfied wait on the condition variable (atomically releasing the lock), and when signaled reacquire the lock and check again. This pattern appears frequently in multi-threaded programming.

Read-write locks optimize scenarios where data is read frequently but modified rarely. These locks allow multiple readers simultaneously (since reading doesn’t cause interference) but require exclusive access for writers. This improves performance for read-heavy workloads while maintaining correctness.

Lock-free data structures avoid locks entirely, using atomic operations that the processor guarantees to execute indivisibly. These structures require careful algorithm design but can provide better performance and avoid deadlock risks. Modern processors provide atomic compare-and-swap operations that enable lock-free programming, though correct implementation is notoriously difficult.

Cooperative vs. Preemptive Multitasking

Operating systems implement multitasking through either cooperative or preemptive approaches, with dramatically different characteristics and implications for system behavior.

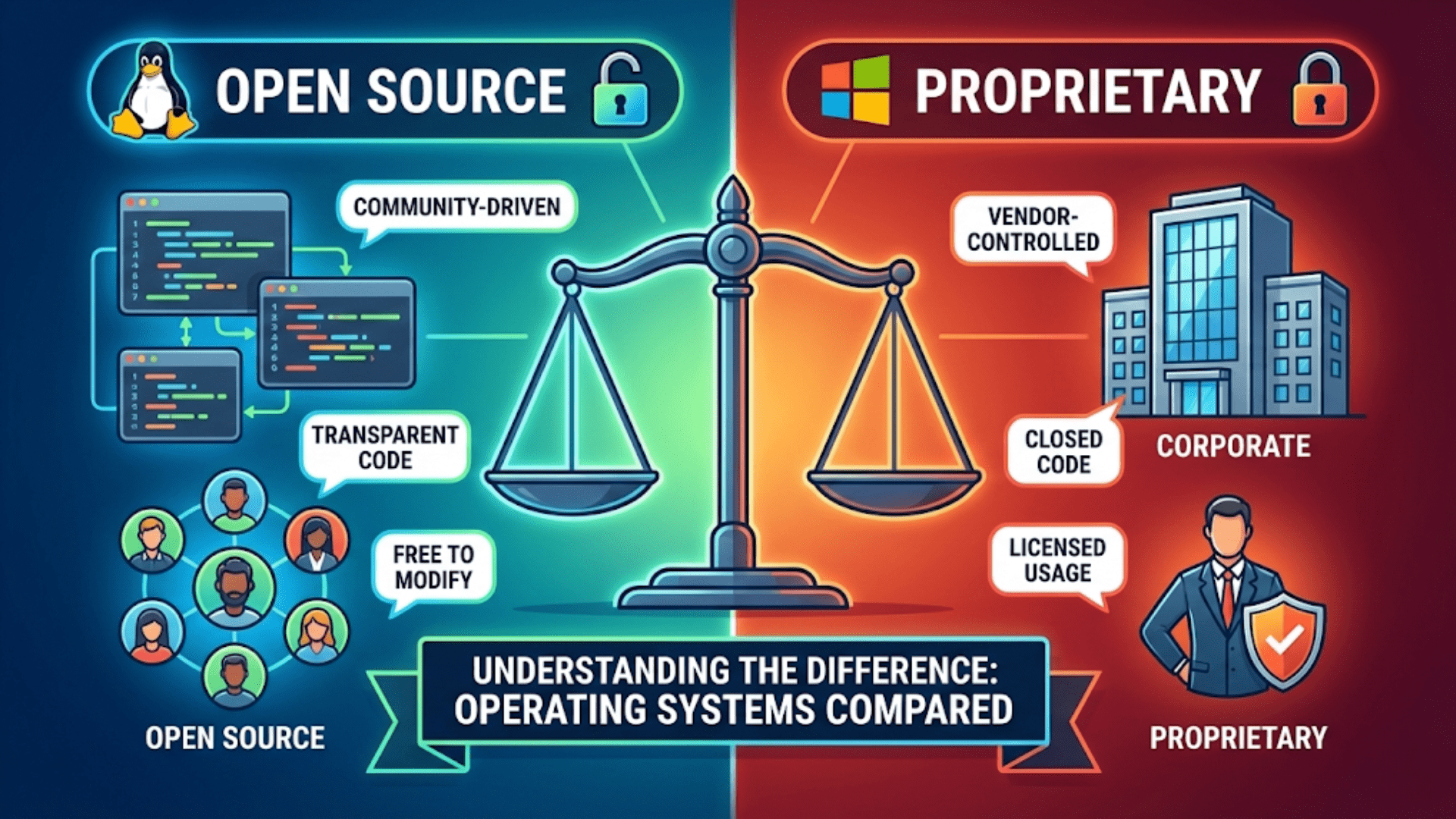

Cooperative multitasking relies on programs voluntarily yielding control to the operating system. Each program runs until it explicitly gives up the processor, either by calling a yield function or by waiting for I/O. This approach has advantages: it’s simple to implement, context switches only occur at well-defined points that programs choose, and programs can complete atomic operations without interruption. However, cooperative multitasking has a critical flaw: a misbehaving or buggy program that never yields can monopolize the processor, freezing the entire system. One stuck program destroys responsiveness for everyone.

Classic Mac OS and Windows 3.x used cooperative multitasking, and their frequent system freezes demonstrated the limitations of this approach. A single misbehaving application could hang the entire system, requiring a reboot to recover. Users had to trust that all running programs were well-behaved—an increasingly untenable requirement as software complexity grew and third-party programs proliferated.

Preemptive multitasking gives the operating system control over task switching. The OS can interrupt any task at any time, switching to another task whether the current one wants to yield or not. Timer interrupts fire at regular intervals (typically 100-1000 times per second), and the interrupt handler invokes the scheduler to decide whether to switch tasks. This preemption ensures that no single task can monopolize the processor—even infinite loops or hung programs won’t freeze the system because the OS forcibly switches them out.

Modern operating systems universally use preemptive multitasking for general-purpose computing. Windows NT (and all subsequent Windows versions), Linux, macOS, iOS, and Android all implement preemptive scheduling. This approach requires more sophisticated operating system design—the OS must protect itself from malicious programs, handle being interrupted at arbitrary points, and ensure system data structures remain consistent despite concurrent access. However, the benefits in responsiveness and robustness far outweigh the increased complexity.

Preemptive scheduling enables fine-grained time sharing that makes multitasking effective. Programs receive frequent short time slices rather than infrequent long ones, maintaining responsiveness even under heavy load. If one program enters an infinite loop, other programs continue running normally. The system remains interactive even when background tasks perform heavy computation.

Some specialized systems still use cooperative multitasking where its simplicity and efficiency matter more than robustness. Embedded systems with trusted software, real-time systems where task behavior is predictable, or systems prioritizing determinism over responsiveness might prefer cooperative approaches. However, for general-purpose computing, preemptive multitasking has proven vastly superior.

I/O and Blocking: Why Multitasking Matters

Much of multitasking’s value comes from handling input/output operations efficiently. I/O operations are extraordinarily slow compared to processor speeds—thousands or millions of times slower. Without multitasking, the processor would sit idle during I/O, wasting valuable computing capacity. Multitasking allows other work to proceed during these waits, dramatically improving system utilization.

When a process requests I/O—reading a file, sending network data, or waiting for user input—the operation doesn’t complete immediately. The operating system issues the I/O request to the appropriate device and marks the process as blocked. Blocked processes aren’t scheduled to run because they’re waiting for external events and wouldn’t be able to make progress even if given processor time. The scheduler selects other ready processes to execute while the I/O proceeds.

Eventually the I/O completes. The device generates an interrupt, the interrupt handler processes the completed operation, and the OS marks the waiting process as ready to run. The scheduler will eventually select it, and it resumes execution with the I/O results available. From the process’s perspective, the I/O operation simply took some time to complete—it doesn’t know or care that other processes ran while it waited.

This I/O handling makes multitasking essential for responsiveness. Consider a single-tasking system where you click a button that requires loading data from disk. The entire system would freeze for dozens of milliseconds—an eternity in computing terms—while waiting for the disk. With multitasking, other programs continue running, the user interface remains responsive to input, and the delay is imperceptible. The system appears to handle many activities simultaneously when actually it’s cleverly using time that would otherwise be wasted waiting.

Asynchronous I/O takes this further, allowing programs to initiate I/O operations and continue executing without waiting for completion. The program requests the I/O, receives a notification when it completes, and proceeds with other work in the meantime. This enables highly efficient single-threaded programs that handle many I/O operations concurrently—web servers serving thousands of connections, for example. While less intuitive to program than synchronous I/O, async I/O achieves excellent performance by eliminating waiting.

Performance Considerations and Optimization

Understanding multitasking helps explain system performance characteristics and guides optimization efforts. Several factors affect how well multitasking performs and how responsive systems feel.

Context switch overhead becomes significant when too many processes compete for processor time. Each switch wastes microseconds that could be spent doing useful work. Systems running hundreds of active processes experience noticeable overhead from constant switching. Reducing the number of running processes—closing unnecessary applications, disabling unneeded background services—can improve performance by reducing this overhead.

Cache effects strongly influence multitasking performance. Processor caches keep frequently accessed data readily available, dramatically speeding access compared to main memory. When context switches occur frequently, caches continuously get flushed and repopulated with different processes’ data, reducing cache effectiveness. This cache thrashing hurts performance. Scheduler algorithms that respect processor affinity—running processes on the same core consistently—help maintain cache effectiveness.

Priority inversion occurs when a high-priority task waits for a low-priority task holding a resource. The high-priority task can’t run despite being ready because it needs a lock held by the low-priority task. Meanwhile, medium-priority tasks might preempt the low-priority task, preventing it from releasing the lock. This inverts the intended priority relationship. Priority inheritance protocols solve this: when a low-priority task holds a resource that a high-priority task needs, temporarily elevate the low-priority task’s priority so it can complete and release the resource quickly.

System monitoring tools reveal multitasking behavior. Task Manager on Windows, Activity Monitor on macOS, or top/htop on Linux show which processes are consuming processor time, how many context switches occur, and how many processes exist in various states. These tools help diagnose performance problems: excessive processes, runaway programs consuming too much CPU, or blocking waiting for I/O.

The number of processor cores dramatically affects multitasking performance. With multiple cores, truly simultaneous execution becomes possible—four cores can execute four threads genuinely at once rather than rapidly switching between them. More cores benefit workloads with many concurrent tasks but show less benefit for single-threaded applications. Modern systems routinely have 4-16 cores, with server systems reaching 64 or more cores, enabling massive parallelism.

The Evolution and Future of Multitasking

Multitasking has evolved continuously as processor architectures, workload characteristics, and user expectations changed. Understanding this evolution provides perspective on current systems and hints at future directions.

Early time-sharing systems in the 1960s pioneered multitasking to share expensive mainframes among many users. These systems established fundamental principles—process isolation, scheduling algorithms, synchronization primitives—that remain relevant today. Personal computers initially abandoned multitasking for simplicity, but demand for running multiple applications forced its reintroduction.

Multi-core processors changed multitasking fundamentally. With multiple cores, the illusion of parallelism became reality—programs could execute truly simultaneously. However, cores also introduced challenges: maintaining cache coherency across cores, scheduling for NUMA architectures, and programming models that effectively exploit parallelism. Operating systems and applications continue adapting to multi-core realities.

Heterogeneous computing with different types of processors—CPU cores, GPU cores, specialized accelerators—requires new scheduling approaches. Operating systems must decide not just when to run tasks but on which type of processor, based on task characteristics and processor capabilities. This heterogeneity will likely increase as specialized hardware becomes more common.

Energy-aware scheduling considers power consumption alongside performance. Mobile devices and laptops need excellent battery life, requiring schedulers that balance performance against energy use. Modern schedulers can put cores to sleep when unneeded, adjust processor frequencies based on workload, and migrate tasks to more efficient cores.

The fundamental challenge of multitasking remains: creating the illusion of simultaneous execution from limited resources while maintaining responsiveness, fairness, and efficiency. Every improvement in processor speed, every increase in core count, and every new workload characteristic drives continued evolution in how operating systems manage multitasking. The sophistication built into modern schedulers allows your computer to seamlessly handle dozens of tasks, responding instantly to your input while processing email, playing music, and running background updates—all appearing effortless despite the extraordinary complexity happening beneath the surface.