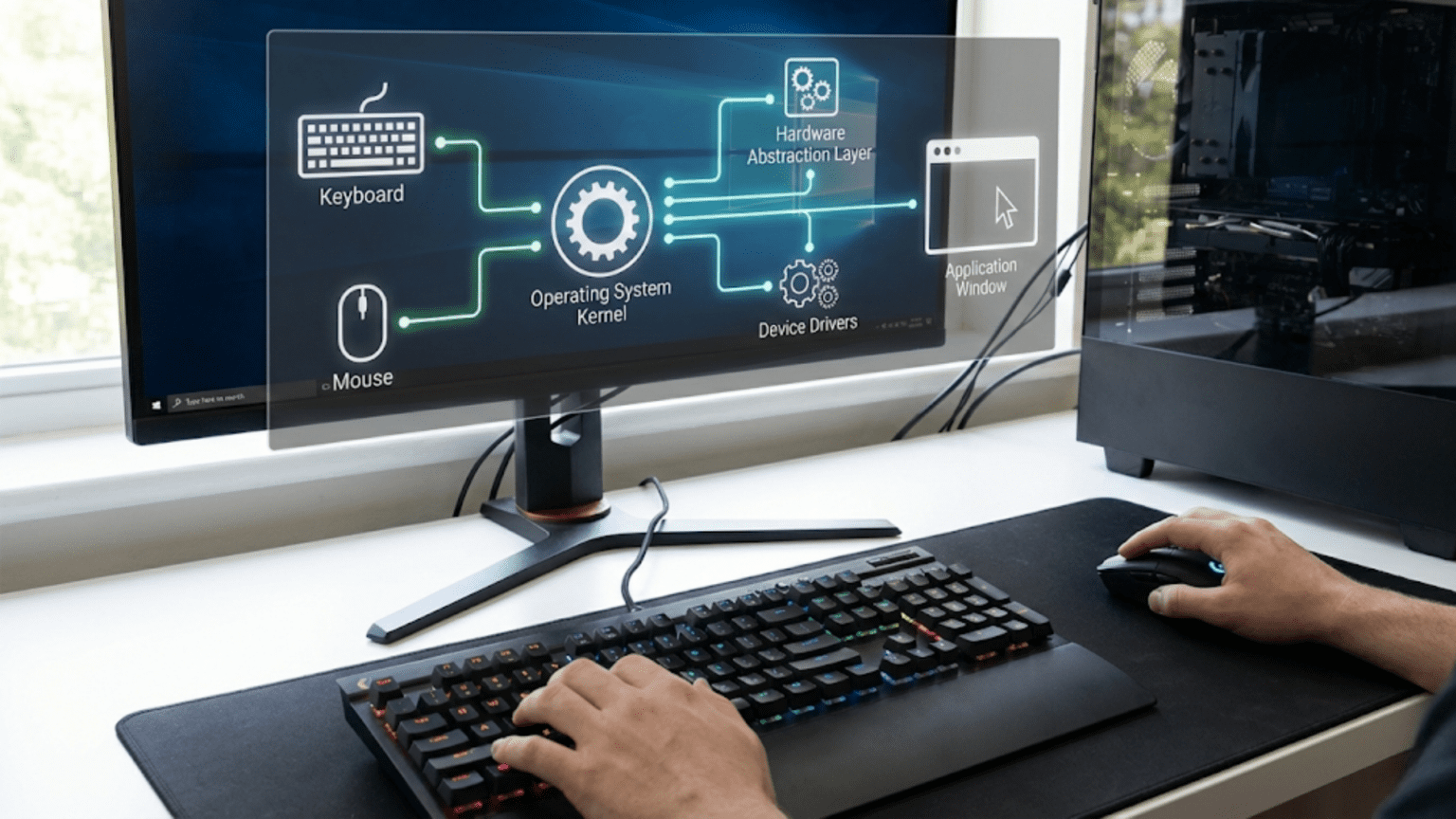

The Journey from Physical Press to Digital Action

When you press a key on your keyboard or move your mouse across your desk, something remarkably complex happens in the milliseconds between your physical action and the response you see on screen. Your simple keystroke triggers a cascade of events involving electronic sensors in your keyboard detecting the physical key press, controller chips encoding that press into digital signals, electrical pathways carrying those signals to your computer, interrupt mechanisms alerting your processor that input has arrived, device drivers translating hardware-specific signals into standardized formats, the operating system determining which program should receive the input, and finally the application processing your keystroke and updating the display accordingly. This entire journey happens so quickly and reliably that you never think about it, yet understanding how operating systems orchestrate this process reveals fascinating insights into the coordination between hardware and software that makes interactive computing possible.

Input devices present unique challenges for operating systems because they generate unpredictable events at unpredictable times that must be handled immediately to maintain the responsive feel that users expect. Unlike many computer operations that happen on the processor’s schedule when it chooses to execute them, input from keyboards and mice arrives whenever you decide to press keys or move the pointer, interrupting whatever the computer was doing to demand immediate attention. The operating system must detect these asynchronous events within milliseconds, determine what they mean in the current context, route them to the appropriate program, and ensure that multiple programs cannot simultaneously receive the same input creating chaos. This real-time responsiveness requirement makes input handling one of the operating system’s more timing-sensitive responsibilities.

Different input technologies require different handling approaches, and the operating system must abstract these differences behind uniform interfaces so that programs can work with any keyboard or mouse without knowing specific hardware details. A mechanical keyboard generates different signals than a membrane keyboard, yet programs see identical keypresses regardless of keyboard type. An optical mouse tracks movement differently than a trackpad, yet the cursor moves identically regardless of input device. This abstraction through device drivers and operating system input subsystems enables the diversity of input hardware we see today while maintaining compatibility with software written decades ago that knows nothing about modern input technology. Understanding this abstraction reveals both how backward compatibility is maintained and how new input devices can be supported without rewriting all existing software.

How Keyboards Generate and Send Signals

The process of converting your physical keypress into digital information begins inside the keyboard itself before any interaction with the operating system occurs. Understanding what keyboards do helps clarify what the operating system must handle when keyboard input arrives.

Inside mechanical and membrane keyboards, pressing a key closes an electrical circuit at that key’s position in a grid or matrix of circuits. The keyboard controller, which is a small dedicated processor inside the keyboard, constantly scans this matrix checking which circuits are closed, thereby detecting which keys are currently pressed. When the controller detects a new keypress, it generates a scan code which is a numeric identifier specific to that physical key’s position on the keyboard. Importantly, the scan code represents the key position rather than the character the key is labeled with, which is why the same physical key produces the same scan code regardless of whether you have configured your keyboard for US English, French, or any other language layout.

When you press a key, the keyboard sends a make scan code to the computer indicating that this particular key was pressed down. When you release the key, the keyboard sends a break scan code indicating the key was released. This press-and-release signaling allows the operating system to track which keys are currently held down, which matters for modifier keys like Shift, Control, and Alt that change the meaning of other keys depending on whether they are pressed when those other keys are activated. The separation of press and release events also enables detecting how long keys are held, which some applications use for special functionality or accessibility features.

The keyboard transmits these scan codes to the computer through the connection interface, whether that is USB for modern keyboards, PS/2 for older ones, or Bluetooth for wireless keyboards. USB keyboards package scan codes into standardized HID, which stands for Human Interface Device, reports that describe the keyboard state including which keys are currently pressed. This standardization means the operating system can communicate with any USB keyboard through the same protocol regardless of manufacturer or model. For PS/2 keyboards, scan codes travel through a dedicated keyboard port using a simpler protocol specific to keyboards. Bluetooth keyboards use wireless transmission protocols to deliver scan code information to Bluetooth receivers, but ultimately present the same logical information as wired keyboards.

When scan codes arrive at the computer, they trigger hardware interrupts that immediately notify the processor that keyboard input has arrived requiring attention. These interrupts are essential for responsiveness because they allow the processor to react to keypresses within milliseconds regardless of what other work it was doing. Without interrupts, the processor would need to constantly check whether keyboard input had arrived, which would waste processor time and delay input handling until the next check occurred. The interrupt mechanism ensures that keyboard input receives immediate attention, maintaining the interactive feel that makes computers usable.

The Operating System’s Keyboard Input Processing

Once scan codes arrive at the computer and trigger interrupts, the operating system takes over processing them through multiple software layers that transform raw scan codes into meaningful events that applications can understand and use.

The keyboard interrupt handler executes immediately when keyboard interrupts arrive, running with high priority to ensure responsive input processing. This handler reads the scan code from the keyboard controller hardware registers where it has been stored, acknowledges the interrupt to allow the keyboard to send more input, and begins processing the scan code. The interrupt handler typically runs in kernel mode with full privileges because it must access hardware directly, but it executes for only microseconds to minimize the time that other operations are blocked waiting for interrupt handling to complete.

The keyboard device driver receives scan codes from the interrupt handler and begins translating them from hardware-specific codes into more standardized representations. The driver understands the particular scan code set that the keyboard uses, whether that is the original XT scan codes, the extended AT scan codes, or USB HID codes, and translates them into a common internal representation. The driver also handles keyboard-specific features like multimedia keys, which might generate special scan codes that need mapping to system functions like volume control or media playback. This driver layer allows the operating system to work uniformly with all keyboards despite them potentially generating different scan codes for equivalent keys.

The keyboard layout engine applies the configured keyboard layout to determine what character or action each keypress represents in the current language and layout configuration. The scan code identifies the physical key position, but what character that position produces depends on the active keyboard layout. On a US keyboard layout, the key position generating scan code 16 produces the letter Q, but on a French AZERTY layout, that same scan code produces the letter A because the physical key layouts differ. The layout engine also processes modifier keys, determining that pressing Shift with the A key should produce uppercase A, or that pressing Control with C should produce a copy command rather than typing the letter C. This layout processing transforms positional scan codes into meaningful character input appropriate for the configured language.

The input focus management determines which program should receive the keyboard input based on which window currently has input focus. On graphical systems, the window you most recently clicked or that the operating system highlighted as active receives keyboard input. The operating system maintains focus state, tracking which window has focus and routing input exclusively to that window’s owning process. This focus management prevents keyboard input from going to multiple programs simultaneously, which would create confusion and potential security issues if background programs could capture everything you type including passwords and sensitive information.

The event queue receives processed keyboard events and holds them until the owning program retrieves them. Rather than forcing programs to handle keyboard input the instant it arrives, which would complicate programming, the operating system queues events and allows programs to retrieve them at convenient times. This queuing means programs can concentrate on their primary work and periodically check for input events, processing accumulated events in batches. The operating system manages these queues, ensuring events are delivered in the order they occurred and handling situations where programs are slow to retrieve events and queues fill up.

How Mice and Pointing Devices Work

Mouse input handling shares similarities with keyboard processing but also has unique characteristics related to tracking continuous motion and positioning rather than discrete keypress events.

Optical mice illuminate the surface beneath them with LED lights and use a small camera to capture rapid images of the surface texture. By comparing consecutive images and detecting how the texture pattern has shifted between frames, the mouse can calculate how far and in what direction it has moved. This movement information is encoded as relative motion values indicating how many units the mouse moved in the X and Y directions since the last report. The mouse microcontroller performs this image processing internally and sends motion reports to the computer dozens or hundreds of times per second depending on the mouse’s polling rate.

Trackpads used on laptops detect finger position through capacitive sensing where the proximity of your conductive finger changes the electrical properties of sensor grids beneath the pad surface. The trackpad controller scans these sensors constantly to determine finger position, detect when fingers press down, and calculate finger movement. Unlike mice that report relative movement, trackpads typically know absolute finger positions within the pad boundaries, though they often convert this to relative movement when emulating traditional mouse behavior. Modern trackpads detect multiple simultaneous finger touches, enabling gestures like two-finger scrolling or pinch-to-zoom that provide more functionality than traditional mice.

Mouse buttons are handled similarly to keyboard keys, with make and break signals indicating when buttons are pressed and released. The mouse controller packages button state changes along with movement information in reports sent to the computer. Middle buttons, side buttons, and scroll wheels are encoded in these reports as well. Some mice have many programmable buttons generating different signals that the operating system or mouse driver software can map to various functions. The scroll wheel typically reports rotational movement as signed values indicating forward or backward scrolling.

USB and wireless mice send HID reports similar to keyboards, using standardized formats that allow operating systems to support any compliant mouse without device-specific drivers. These reports contain fields indicating X movement, Y movement, button states, and scroll wheel position changes. The polling rate determines how frequently the mouse sends reports, with higher rates providing smoother tracking at the cost of more USB bandwidth and processor overhead. Gaming mice often support very high polling rates for minimal latency, while basic mice use lower rates that are sufficient for general use.

The Operating System’s Mouse Input Processing

The operating system processes mouse input through similar layering as keyboard input but with specific handling for the continuous nature of pointer movement and positioning.

The mouse interrupt handler responds to interrupts generated when the mouse sends reports, reading the movement and button data from the USB controller or other interface. Similar to keyboard handling, this interrupt handling happens immediately with high priority to ensure responsive pointer movement. The interrupt handler extracts the raw movement values and button states from the mouse reports and passes them to higher-level processing.

The mouse device driver translates raw mouse reports into standardized movement and button events that the operating system’s input subsystem can process uniformly regardless of mouse brand or model. The driver applies any sensitivity or acceleration settings that scale raw mouse movement to pointer movement at rates comfortable for users. Some drivers for gaming mice or specialized input devices provide additional functionality like customizable button mapping or DPI switching that changes sensitivity on the fly.

The cursor position calculation integrates relative mouse movements into absolute screen coordinates that determine where the pointer appears. When the mouse reports that it moved five units right and three units down, the operating system adds these values to the current pointer position to calculate the new position. The operating system enforces screen boundaries, preventing the pointer from moving outside visible screen area even if the mouse continues moving. On multi-monitor setups, the operating system manages pointer transition between displays, making the pointer appear to move seamlessly across monitor boundaries.

Acceleration curves modify the relationship between physical mouse movement and pointer movement to make the pointer easier to control. Without acceleration, moving the mouse one inch always moves the pointer the same distance on screen regardless of how fast you move the mouse. With acceleration, moving the mouse slowly provides precise control with small pointer movements, while moving the mouse quickly generates larger pointer movements allowing you to traverse the screen efficiently. This non-linear response helps users achieve both precision for detailed work and speed for moving long distances with the same mouse.

Button click processing converts mouse button presses into click events that applications receive. The operating system tracks button press and release timing to distinguish single clicks from double clicks, which require two rapid clicks on the same button. It also generates drag events when the mouse moves while a button is held down, enabling selection and object movement operations. Right-clicks, middle-clicks, and clicks on additional buttons all generate distinct events that applications can handle differently.

Window hit testing determines which window the pointer is currently over, which is necessary for determining where mouse clicks should be directed and which window should highlight in response to pointer hovering. The operating system maintains the screen layout including where all windows are positioned and uses the cursor coordinates to identify which window, if any, is at that position. This hit testing happens constantly as the pointer moves to enable proper event routing and visual feedback.

Input Focus and Event Routing

The operating system must ensure input reaches the correct program even when many programs are running simultaneously, which requires careful management of input focus and event delivery.

Keyboard focus determines which program receives keyboard input and typically follows window activation, with the most recently activated window receiving keystrokes. Users change keyboard focus by clicking windows, using Alt-Tab or similar shortcuts to switch between applications, or through other window management operations. The operating system maintains keyboard focus state and routes all keyboard events to the program owning the focused window, preventing background programs from capturing keyboard input which could enable password theft or other malicious activities.

Mouse focus is more complex than keyboard focus because the pointer can be over different windows as it moves, and mouse clicks on inactive windows typically activate those windows changing keyboard focus simultaneously. The operating system tracks which window the pointer is currently over and routes mouse movement events to that window, allowing programs to respond to the pointer being over their content even when they do not have keyboard focus. Mouse clicks on window content typically activate that window, giving it keyboard focus in addition to receiving the click event.

Input event delivery happens through message queues where the operating system places events for programs to retrieve and process. Each program has an input queue that receives events directed to its windows. Programs periodically check their queues, retrieving and processing accumulated events. This asynchronous event handling allows programs to maintain control over their execution flow rather than having input handling interrupt them unpredictably.

Global hotkeys and system-level input handling allows the operating system to intercept certain input combinations before applications see them, enabling system functions that work regardless of which application has focus. Combinations like Alt-Tab for window switching or Control-Alt-Delete for security options are handled at the operating system level and never delivered to applications. This system-level interception ensures critical functions remain accessible even if applications are hung or misbehaving.

Accessibility input modification enables assistive technologies to modify or intercept input to help users with disabilities. Screen readers capture keyboard input to provide voice feedback, on-screen keyboards generate keyboard events from mouse clicks, and sticky keys modify modifier key behavior to help users who cannot press multiple keys simultaneously. The operating system provides hooks that allow these assistive technologies to inject into input processing while maintaining security against malicious input interception.

Input Buffering and Timing

The operating system must manage timing-related aspects of input to ensure responsive behavior and proper handling of rapid input sequences.

Keyboard repeat implements the familiar behavior where holding a key initially generates one character event, then after a brief delay begins generating repeated events at regular intervals until the key is released. The operating system manages this repeat behavior by tracking how long keys have been held and generating synthetic press events at appropriate intervals. Users can configure the initial delay before repeating begins and the repeat rate through control panel settings, customizing keyboard behavior to their preferences.

Typematic rate control manages keyboard repeat timing through settings that determine the delay before repeat begins and how quickly characters repeat once started. These settings significantly affect typing comfort and are highly individual preferences. Some users prefer aggressive repeat for quickly filling fields, while others prefer conservative repeat to avoid accidental multiple characters.

Mouse double-click timing determines how quickly two clicks must occur to be recognized as a double-click rather than two separate single clicks. This timing needs to be fast enough that deliberate double-clicks are recognized but slow enough that users can reliably double-click without requiring perfect timing. The operating system provides configuration for this timing through accessibility settings, and tracks click timing against these thresholds to detect double-clicks.

Input buffering during high load ensures input is not lost even when the system is busy. If the processor is heavily loaded and programs are slow to retrieve input events from their queues, the operating system buffers events rather than discarding them. This buffering has limits to prevent unbounded memory consumption, but typically accommodates hundreds or thousands of queued events, far more than normal input rates generate. This ensures your typing is not lost even during momentary system slowdowns.

Latency minimization throughout input processing attempts to keep total delay from physical action to screen response as low as possible. The operating system uses high-priority interrupt handling, efficient driver code, and direct event routing to minimize processing time. For gaming and professional applications where input latency matters greatly, operating systems provide mechanisms to reduce latency further, though sometimes at the cost of power consumption or system overhead.

Understanding how operating systems handle input devices reveals the sophisticated processing that makes keyboards and mice responsive and reliable. From scan codes and interrupts through device drivers and event queues to focus management and event delivery, every component plays a role in ensuring your keystrokes and mouse movements reach the right programs quickly and correctly. The next time you type or move your mouse, appreciate the complex coordination between hardware and software that makes this simple interaction work seamlessly, transforming physical actions into digital events that drive the applications you use every day.