Protecting Your Data Through Access Control

Every file on your computer—documents, photos, system files, application data—exists in a delicate balance between accessibility and security. You need to access your own files easily while preventing unauthorized users, malicious software, or accidental mistakes from corrupting or stealing your data. Operating systems solve this challenge through file permissions, a sophisticated system that controls exactly who can do what with each file. Understanding file permissions reveals fundamental security principles, explains why certain operations require passwords or administrator access, and empowers you to protect sensitive information while maintaining the convenience of easy access to files you use daily.

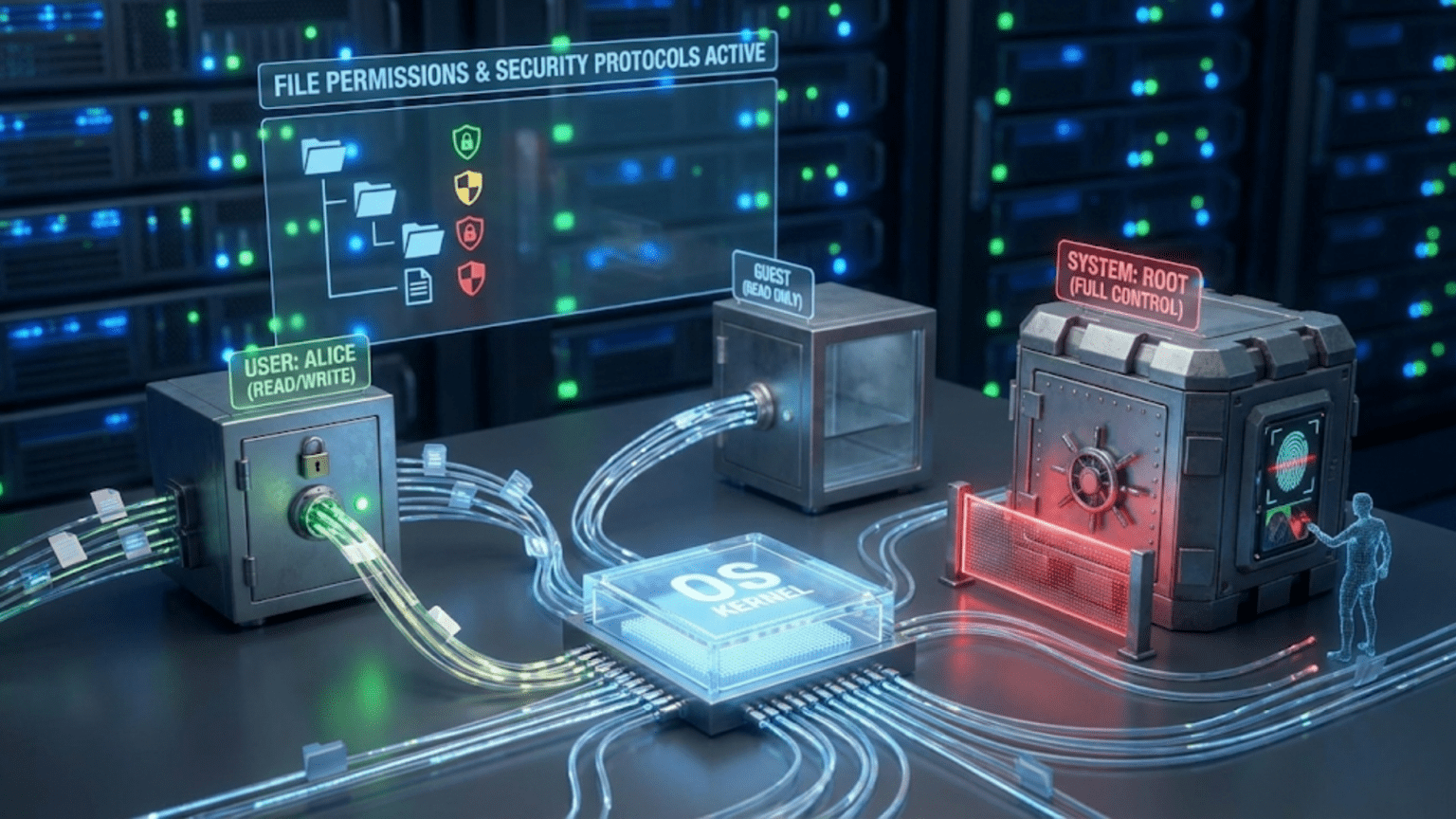

File permissions operate on a seemingly simple principle: each file has an owner, and that owner can specify who else can access the file and what they can do with it. However, beneath this simple concept lies remarkable complexity. Different operating systems implement permissions differently—Unix-like systems use a straightforward model based on owner, group, and others, while Windows employs a more complex system of access control lists with fine-grained permissions. Modern systems add layers of additional security through mandatory access control, file system encryption, and application sandboxing. All these mechanisms work together to create the security environment that protects your data from threats while allowing legitimate access.

The stakes for getting file permissions right are substantial. Permissions that are too restrictive prevent users from accessing files they need, causing frustration and potentially forcing workarounds that undermine security. Permissions that are too permissive allow unauthorized access, enabling data theft, corruption, or system compromise. Finding the right balance requires understanding how permissions work, what threats they protect against, and how to configure them appropriately for your needs. This knowledge transforms file permissions from mysterious technical details into tools you can use effectively to protect your data.

The Basic Permission Concepts: Read, Write, Execute

At the heart of most file permission systems lie three fundamental actions that users might perform on files: reading, writing, and executing. Understanding these basic permissions provides the foundation for more complex security concepts.

Read permission allows viewing file contents or listing directory contents. With read permission on a document, you can open it and see what it contains. With read permission on a directory, you can list what files and subdirectories it contains. Read permission doesn’t allow changes—only inspection. This permission is essential for consuming information but doesn’t inherently risk modifying or damaging files. However, read permission on sensitive files does risk information disclosure, which can be as serious as data modification in many contexts. Financial records, personal communications, and business secrets all require careful control of read access.

Write permission allows modifying file contents, creating new files in directories, or deleting files from directories. With write permission on a document, you can edit it, potentially corrupting or destroying information if changes are inappropriate. With write permission on a directory, you can add or remove files within it. Write permission carries obvious risks—accidental or malicious modifications can destroy data or introduce errors. The principle of least privilege suggests granting write permission only when modification is genuinely needed, using read-only access when files need to be consulted but not changed.

Execute permission allows running files as programs or entering directories. On files, execute permission means the operating system will treat the file as a program and run its instructions. Without execute permission, attempting to run a file fails even if you can read and write it. On directories, execute permission means you can “enter” that directory—make it your current directory or access files within it if you know their names. This distinction between read and execute for directories enables interesting security scenarios: you might be unable to list a directory’s contents (no read permission) but still access specific files if you know their names (having execute permission).

The combination of these three permissions creates eight possible permission states for each file, from no permissions (000 in octal notation) through full permissions (111, or 7 in octal). Different combinations serve different purposes. Read-only (100 or 4) allows viewing but not changing. Read-write (110 or 6) allows both viewing and modification but not execution. Read-execute (101 or 5) allows viewing and running but not modification, common for program files that shouldn’t be altered. Understanding these combinations helps you configure permissions appropriately for different file types and security requirements.

Unix-Style Permissions: Owner, Group, Others

Unix-like operating systems including Linux and macOS use a straightforward permission model that’s been refined over decades. Understanding this model reveals elegant simplicity in permission management.

Every file has an owner—the user account that created the file or was assigned ownership. The owner typically has full control over the file, able to read, write, and modify permissions. This ownership creates accountability and default access—you naturally have control over files you create. Ownership can be changed by administrators, transferring control to different users when needed. The owner’s permissions apply specifically to them, allowing generous self-access while restricting others more tightly.

Every file also has a group—a collection of user accounts treated as a unit for permission purposes. Groups enable sharing files among teams without granting universal access. For example, a “developers” group might have write access to code repositories, while other users have only read access or no access. Group permissions apply to all users who belong to the file’s group, providing a middle ground between owner-only access and universal access. Users can belong to multiple groups, accumulating permissions from each.

The “others” category includes all users who aren’t the owner and don’t belong to the file’s group. Permissions for others specify what everyone else can do with the file. Setting generous permissions for others makes files widely accessible, while restrictive others permissions limit access to the owner and group. This three-tier model—owner, group, others—provides sufficient flexibility for most scenarios while remaining simple enough to understand and manage.

The familiar rwxrwxrwx notation shows these permissions compactly. The first three characters show owner permissions (read, write, execute), the second three show group permissions, and the final three show others permissions. For example, rw-r--r-- means the owner can read and write, while group and others can only read. The chmod command modifies these permissions, using either symbolic notation (chmod u+x file adds execute for the owner) or numeric notation (chmod 644 file sets specific permissions).

Special permission bits extend the basic model. The setuid bit makes programs run with the file owner’s privileges rather than the user executing them, enabling controlled privilege escalation. The setgid bit on directories causes new files created within to inherit the directory’s group rather than the creator’s default group. The sticky bit on directories prevents users from deleting files they don’t own, even if they have write permission on the directory—useful for shared temp directories. These special bits enable advanced scenarios while building on the same fundamental permission concepts.

Windows Access Control Lists: Fine-Grained Permissions

Windows takes a more complex but also more flexible approach to file permissions through Access Control Lists (ACLs), which provide fine-grained control over exactly who can do what with each file.

Each file or directory has an ACL—a list of access control entries (ACEs) that specify permissions for specific users or groups. Rather than the simple three-category model of Unix systems, Windows ACLs can contain entries for any number of users or groups, each with different permissions. This flexibility allows precise control: “Alice can read and write, Bob can only read, the Administrators group has full control, and everyone else has no access.” Such specific configurations would be awkward in Unix-style permissions but are natural in the ACL model.

Windows permissions are more granular than simple read/write/execute. They include permissions like “delete,” “change permissions,” “take ownership,” “read attributes,” “write attributes,” and many others. These fine-grained permissions enable precise control over specific actions. You might allow users to modify file contents but not delete the file entirely, or allow reading file attributes without reading contents. This granularity serves enterprise scenarios where detailed access control is essential, though it adds complexity compared to simpler models.

Permission inheritance propagates permissions from parent directories to child files and directories automatically. When you set permissions on a folder, you can specify that those permissions should apply to existing and future contents. This inheritance dramatically reduces administrative overhead—you configure permissions once on a top-level folder rather than repeatedly on every file. However, inheritance can be disabled for specific items, allowing exceptions to inherited permissions where needed. Understanding inheritance is crucial for effective Windows permission management because most permissions are inherited rather than explicitly set.

Explicit permissions override inherited permissions, allowing specific exceptions to general policies. If a folder grants read access to everyone through inheritance, you can explicitly deny access to specific users on particular files within. Deny permissions take precedence over allow permissions, providing a way to revoke access even when multiple ACEs would otherwise grant it. This precedence system enables “allow by default, deny exceptions” policies that are often the most practical approach.

Effective permissions represent what a user can actually do after considering all applicable ACEs, including inherited and explicit permissions, allows and denies, and group memberships. Windows provides tools to view effective permissions, showing the net result of all permission rules for a specific user on a specific file. These tools help administrators verify that permission configurations produce intended results, especially in complex scenarios with many interacting rules.

File Ownership and Permission Changes

Understanding who owns files and who can change permissions reveals important security properties and explains why certain operations require administrator access.

File creation typically assigns ownership to the user who created the file, with the file’s initial permissions coming from system defaults or parent directory settings. This automatic ownership ensures users have control over their own files by default. On Unix systems, the file’s group is typically the user’s primary group or inherited from the parent directory. On Windows, ownership goes to the creating user, with permissions often inherited from the parent directory’s ACL.

Changing ownership requires privilege because ownership conveys control. On Unix systems, only administrators (root) can change file ownership—even owners cannot give their files to other users without administrator intervention. This restriction prevents users from escaping disk quotas or responsibility by transferring ownership. Windows allows “take ownership” as a distinct privilege, which administrators have but can also be granted to specific users. Taking ownership is one-way—you can take ownership of files you have the privilege for, but you cannot give ownership to others without administrator rights.

Changing permissions typically requires being the file’s owner or having administrator privileges. Owners can modify permissions on their files, granting or restricting access as they see fit. This control is fundamental to the security model—owners decide who can access their files. However, administrators can override owner permissions, changing permissions on any file as part of their system management responsibilities. This administrative override is necessary for system maintenance but represents a trust relationship—administrators must be trusted not to abuse their access.

The immutable bit or file attributes can prevent even administrators from modifying certain files until the protection is removed. On Linux, the immutable flag prevents file modification, deletion, or renaming, even by root. Windows has similar attributes like read-only and hidden. These protections guard against accidental damage to critical files and can slow down attackers who gain administrative access, though they’re not foolproof—administrators can remove the protections before modifying files.

Permission Checking and Enforcement

Understanding how operating systems actually enforce permissions reveals the mechanisms that make access control reliable.

Every file access attempt triggers permission checking. When a program tries to open a file, the operating system examines the current user’s identity and permissions on that file. Only if the checks pass does the operation proceed. This checking happens in the kernel, where user-mode programs cannot bypass it. Even if malicious software tries to access unauthorized files, the kernel enforces permissions, blocking unauthorized access.

User identity matters crucially for permission checking. The operating system maintains a security context for each process, identifying which user account the process is running as. All file access from that process uses that user’s identity for permission checks. This identity-based checking prevents one user’s processes from accessing another user’s files, even though both sets of processes run on the same system simultaneously.

Process credentials can change through privilege elevation mechanisms. When you run a program as administrator on Windows or use sudo on Unix, the process’s security context changes to reflect elevated privileges. Permission checks for that process now use the elevated identity, granting access to files that would otherwise be restricted. This temporary elevation allows performing administrative tasks without running everything with full privileges, following the principle of least privilege.

The kernel maintains cached permission information for performance. Checking permissions for every file access could create significant overhead, so operating systems cache permission data and security contexts. However, permission changes must invalidate relevant caches to ensure current permissions apply immediately. This caching makes permission enforcement efficient while maintaining security.

Common Permission Scenarios and Solutions

Understanding typical permission challenges and their solutions helps you configure systems effectively.

Sharing files among team members requires appropriate group permissions or ACL entries. On Unix systems, create a group containing team members, assign that group to shared files, and grant the group appropriate permissions. On Windows, create an ACL entry allowing the team’s group or individual members. Proper sharing provides necessary access without overly permissive settings that allow unauthorized access.

Protecting sensitive files from unauthorized access means restrictive permissions allowing only yourself and trusted administrators. On Unix, use 600 or 400 permissions (owner read/write or owner read-only). On Windows, remove inherited permissions and explicitly grant access only to yourself and administrators. This restriction prevents casual browsing by other users while maintaining administrator access for system management.

Making files publicly readable but not writable allows sharing information without risk of unauthorized modification. Unix 644 permissions (owner read/write, others read-only) serve this purpose well. Windows ACLs should grant read permission to “Everyone” or “Users” while restricting write access appropriately. This configuration is common for documentation, reference files, or any information meant for wide distribution without allowing changes.

Executable files require different permissions than documents. Programs need execute permission, typically 755 on Unix (owner read/write/execute, others read/execute) or similar ACL entries on Windows. This allows the owner to modify the program while letting everyone run it. Scripts combine executable and read permissions since interpreters must read script contents to execute them.

Directories need specific permissions for their intended use. For browsing, read and execute permissions (755) allow listing contents and accessing files. For adding files, write and execute (733 or 773) allow creation within. For shared directories, group write and sticky bit (1773) allow sharing while preventing users from deleting each other’s files. Understanding these directory permission patterns helps configure shared spaces effectively.

Advanced Security: Beyond Basic Permissions

Modern operating systems implement additional security mechanisms that work alongside basic file permissions to provide defense in depth.

Access Control Lists provide fine-grained permissions on systems supporting them, allowing specific users or groups to have specific permissions that don’t fit the simple owner/group/others model. Windows uses ACLs extensively, but Linux also supports ACLs through extended attributes, providing Windows-like flexibility when needed. ACLs enable complex sharing scenarios and precise access control that basic permissions cannot express.

Extended attributes store additional metadata with files, including security labels, encryption status, or application-specific information. Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) uses extended attributes to store security contexts that mandatory access control uses. These attributes extend file information beyond traditional permissions, enabling advanced security policies and features.

Mandatory Access Control (MAC) enforces system-wide security policies that users cannot override. SELinux, AppArmor on Linux, and Mandatory Integrity Control on Windows implement MAC, defining what processes can access based on security labels and policies. MAC provides additional protection beyond discretionary access control (regular permissions), preventing even administrators from violating security policies without explicitly disabling enforcement.

File system encryption protects data confidentiality even when unauthorized users have physical access. BitLocker on Windows, FileVault on macOS, and LUKS on Linux encrypt entire filesystems or individual folders, requiring proper credentials to decrypt and access. Encryption protects against offline attacks where attackers boot alternative operating systems or remove storage devices, bypassing normal permission checks.

Application sandboxing restricts what files applications can access regardless of filesystem permissions. Mobile operating systems extensively use sandboxing—each app accesses only its own data directory and must request permission for other locations. Desktop systems increasingly adopt sandboxing for untrusted applications, limiting potential damage from compromised or malicious programs even when they run with user privileges.

Troubleshooting Permission Problems

Permission issues are common, and knowing how to diagnose and fix them saves significant frustration.

“Access denied” or “Permission denied” errors indicate insufficient permissions for attempted operations. Check who owns the file, what permissions it has, and whether your user account or groups should have access. On Unix, ls -l shows permissions and ownership. On Windows, the Security tab in Properties shows ACL details. Comparing your identity and permissions reveals whether the denial is correct or misconfigured.

Operations requiring administrator access fail without elevation. Installing software, modifying system files, or changing certain settings need administrator privileges. On Windows, right-click and “Run as administrator.” On Unix/Linux, use sudo. If you lack administrator credentials, you’ll need someone who does to perform privileged operations. This restriction protects the system from unauthorized changes.

Inherited permissions can cause unexpected behavior on Windows when local settings conflict with inherited ones. If a file has access you didn’t explicitly grant, check parent directories for inherited permissions. You can disable inheritance for specific files if needed, though understanding why inheritance is configured that way should precede disabling it—there might be good reasons for the inherited permissions.

Group membership changes may not take effect immediately. On Unix systems, group changes require logout and re-login to update the user’s group list. Processes retain their original group memberships until restarted. This delay can cause confusion when permission changes don’t immediately affect access—the solution is often simply logging out and back in.

Locked files or “in use” errors sometimes relate to permissions but often reflect files being open by processes. While technically not permission issues, they prevent operations and are often confused with permission problems. Close programs using the file or restart the system to release locks. True permission issues persist across restarts, while lock issues typically clear.

Best Practices for File Permissions

Following established best practices helps maintain security while preserving usability.

Apply the principle of least privilege—grant only the minimum permissions necessary for each user’s needs. Users who only need to read files shouldn’t have write access. Programs that don’t need to modify system files shouldn’t run with administrator privileges. This principle limits potential damage from accidents or security breaches.

Use groups for shared access rather than granting permissions to individual users repeatedly. Groups simplify management—add or remove users from groups rather than modifying permissions on many files. Groups also document intent—a “developers” group clearly indicates purpose, while individual user permissions might be arbitrary.

Keep sensitive files in restricted directories with minimal access permissions. Don’t scatter confidential documents throughout filesystem where they’re harder to protect. Centralized sensitive storage with strict permissions provides better security than trying to secure individual files everywhere.

Regularly audit permissions on important files and directories, ensuring configurations remain appropriate as users and requirements change. People leave organizations, projects complete, needs evolve—permissions should adapt accordingly. Periodic reviews catch permission drift where accumulated changes result in inappropriate access.

Document permission rationales for non-obvious configurations. When you grant unusual permissions or restrict access surprisingly, document why. Future administrators (including your future self) will appreciate understanding the reasoning rather than guessing whether strange permissions are intentional or accidental.

Test permissions from affected users’ perspectives to verify configurations work as intended. Log in as different users or use tools that show effective permissions to confirm settings provide intended access without unintended exposure. Testing reveals misconfigurations before they cause problems or security incidents.

The Future of File Permissions and Security

File permission systems continue evolving to address new threats and computing models.

Attribute-based access control might increasingly supplement or replace traditional identity-based permissions. Rather than “Alice can read this file,” policies might state “users in the finance department accessing from corporate networks during business hours can read financial files.” This context-aware access control adapts to circumstances rather than static relationships.

Zero-trust security models assume breaches are inevitable and verify every access regardless of prior authentication. File access would require continuous authentication and authorization, not just initial login. This paranoid approach better protects against compromised credentials and insider threats, though it requires more sophisticated infrastructure.

Blockchain and distributed ledgers might provide tamper-evident audit logs for sensitive file access, creating permanent records of who accessed what when. These immutable logs would help detect unauthorized access and provide accountability that traditional logs lack since attackers can modify or delete conventional log files.

Machine learning might detect anomalous file access patterns indicating security breaches. Systems could learn normal access patterns and alert when behavior deviates—perhaps someone accessing far more files than usual or accessing files outside their normal scope. This behavioral analysis would complement traditional permission checking.

File permissions represent fundamental operating system security that protects your data daily. Understanding how they work, how to configure them appropriately, and how to troubleshoot problems empowers you to protect sensitive information while maintaining necessary access. The next time you encounter a permission error or need to share files with specific people, you’ll understand the security principles involved and how to achieve your goals while maintaining appropriate protection. Good permission management balances security and usability, achieving both through informed configuration that applies well-understood principles to specific situations.