The Invisible Conversation That Stores and Retrieves Your Data

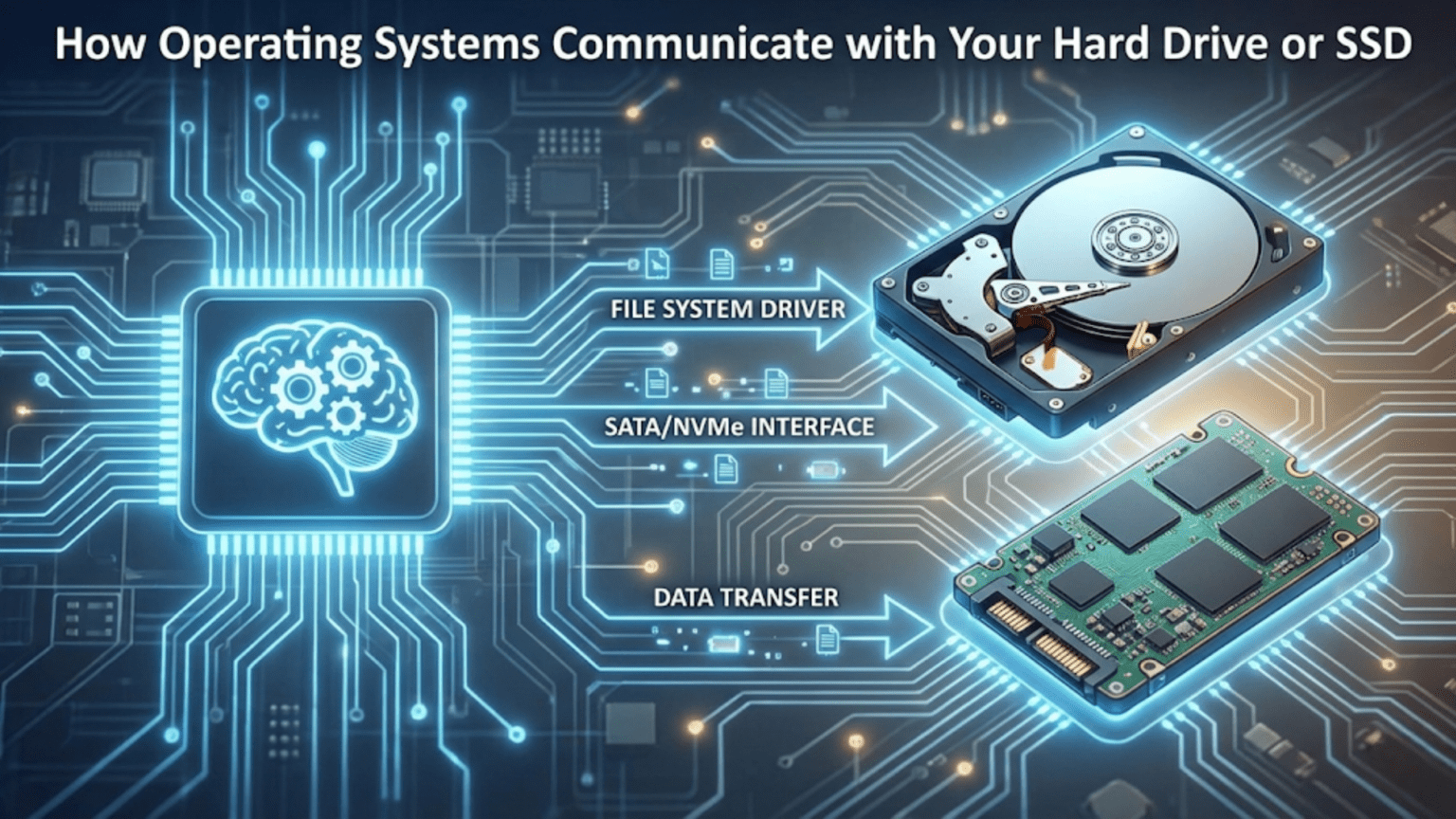

Every time you save a document, download a file, or install a program, your operating system engages in an intricate conversation with your storage devices to ensure your data gets written correctly and can be retrieved later exactly as it was stored. This communication happens so seamlessly that you simply click “Save” and trust that your work is preserved safely on your hard drive or solid-state drive. Behind this simple action lies a sophisticated multi-layered system involving file systems that organize data logically, device drivers that translate between the operating system and storage hardware, communication protocols that govern how data moves between components, and controller hardware inside the storage device that manages the physical process of writing bits to magnetic platters or flash memory chips. Understanding how operating systems communicate with storage reveals the remarkable engineering that makes reliable data storage possible and explains why different storage technologies perform so differently despite all appearing as simple drives to users.

The challenge of storage communication comes from bridging the enormous gap between how humans think about data and how storage devices physically work. When you think about saving a document, you conceptualize it as a single coherent file with a name like “Report.docx” located in a folder called “Documents.” The storage device, however, knows nothing about files or folders or meaningful names. It only understands reading and writing fixed-size blocks of data at specific physical locations identified by numerical addresses. The operating system must translate between these two completely different representations, maintaining the illusion of a hierarchical file system with named files and folders while actually managing thousands or millions of data blocks scattered across the storage device with no inherent organization. This translation happens through multiple software layers that each add abstraction and functionality, creating the user-friendly storage experience you rely on.

Different storage technologies require different communication approaches because their physical characteristics vary dramatically. Traditional hard disk drives use rotating magnetic platters with moving read/write heads that must physically seek to different locations, making access times heavily dependent on how far the head must move and in what order operations are performed. Solid-state drives use flash memory with no moving parts, providing much faster random access but introducing complexities like wear leveling that spreads writes across memory cells to extend lifespan and garbage collection that maintains performance. The operating system must understand these technological differences and adapt its communication patterns accordingly. What works well for hard drives might perform poorly on SSDs and vice versa, so the storage stack includes device-specific optimizations that ensure each technology performs optimally despite the same high-level file system interfaces being used for both.

The Storage Stack: Layers of Abstraction

Understanding storage communication requires recognizing the multiple layers involved, each providing different abstractions and services that build upon the layers below. This layered architecture allows changing individual components without affecting others, enabling new storage technologies to be supported without rewriting application software.

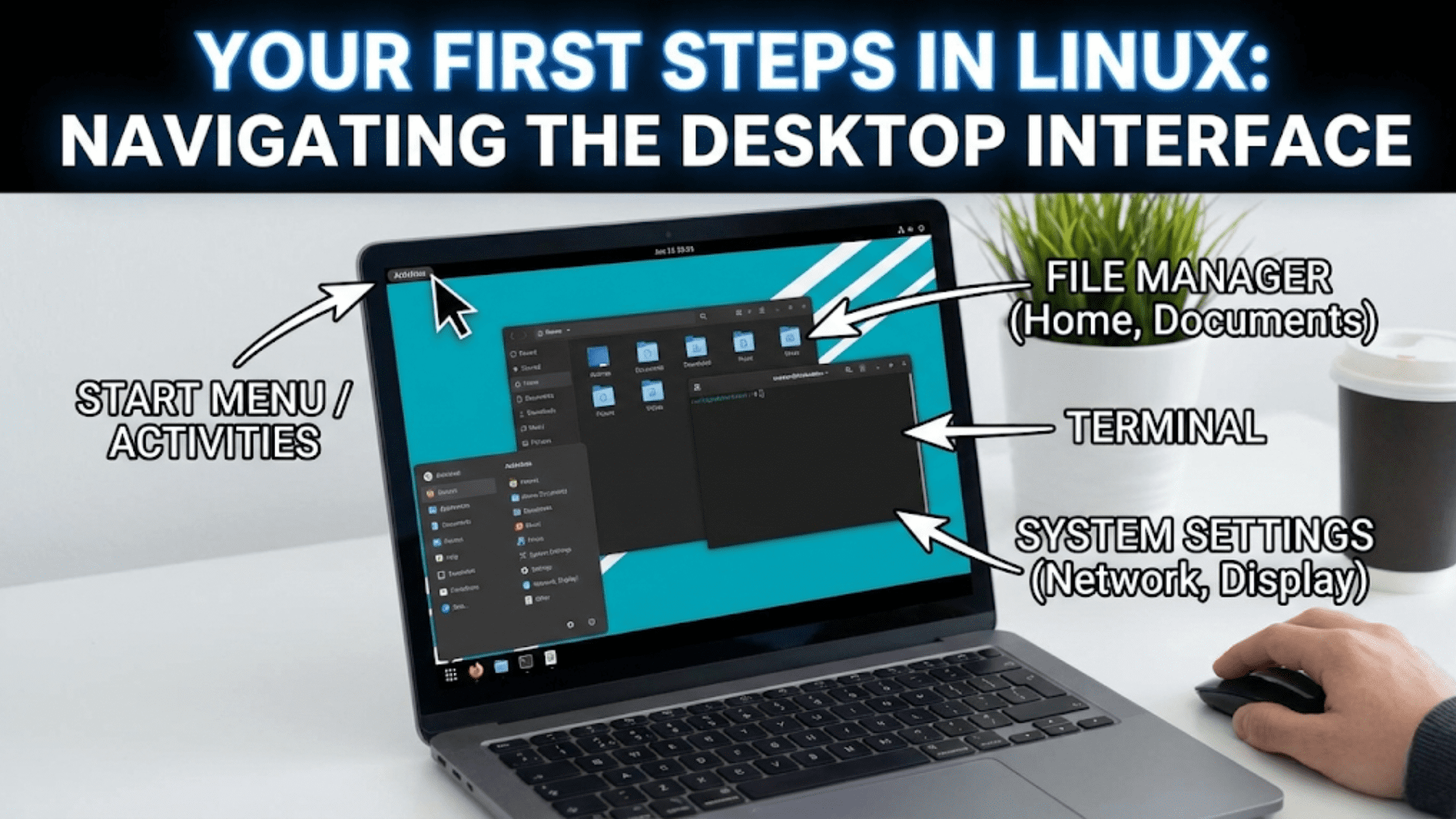

At the highest level, applications work with files through simple operations like open, read, write, and close without any knowledge of how storage devices actually work. When a program wants to read a file, it asks the operating system to open the file by name, providing a path like “C:\Documents\Report.docx” on Windows or “/home/user/documents/report.docx” on Linux. The operating system returns a file handle or descriptor that the program uses for subsequent operations. The program then reads data from this handle using simple read commands that return the requested number of bytes. This high-level interface is intentionally simple because it allows programmers to work with files without understanding the complexities of file systems, device drivers, or storage hardware.

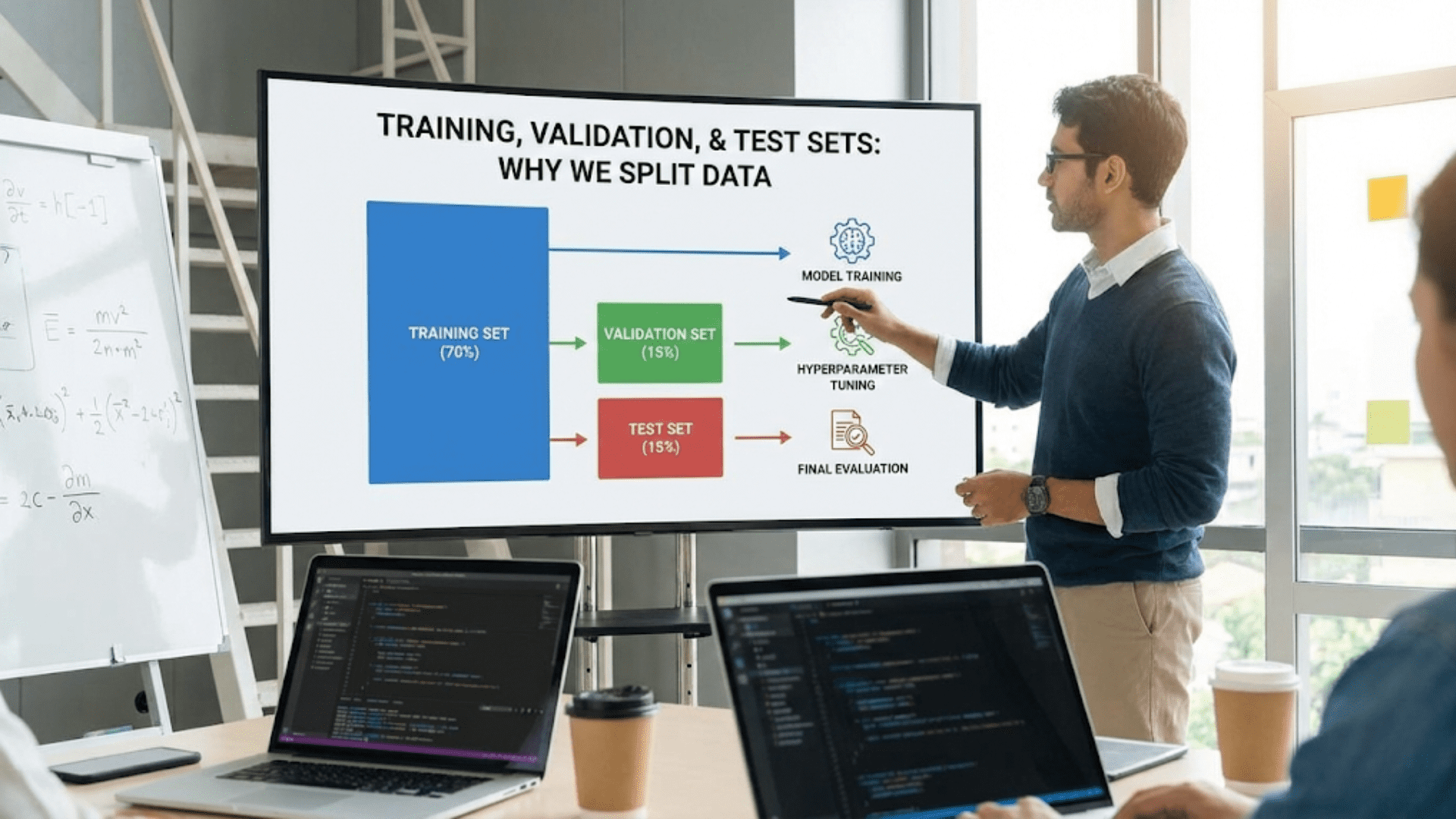

The file system layer translates these high-level file operations into lower-level block operations. When an application opens a file, the file system searches directory structures to locate metadata describing where the file’s data blocks are physically stored on the device. When the application reads from the file, the file system determines which blocks contain the requested data and issues block read requests to the layers below. The file system maintains all the data structures that create the illusion of organized hierarchical storage including directories, file allocation tables, inodes, and extent maps that track which disk blocks belong to which files. Different file systems like NTFS on Windows, APFS on macOS, or ext4 on Linux organize this information differently but all provide similar high-level functionality.

The block device layer presents storage devices as simple arrays of numbered blocks, typically 512 bytes or 4096 bytes each. This layer handles buffering and caching of blocks to improve performance, queuing of read and write operations, and basic error handling. The block layer isolates the file system from device-specific details by presenting a uniform block-based interface regardless of whether the underlying hardware is a hard drive, SSD, or something else entirely. This abstraction allows file systems to work with any storage technology without modification.

The device driver layer handles the actual hardware-specific communication with storage controllers. Each type of storage interface whether SATA, NVMe, SCSI, or USB has its own driver that knows the specific commands and protocols that interface uses. The driver translates generic block read and write requests into the command sequences that the particular hardware understands, sends those commands through the appropriate communication channel, waits for completion, and handles any errors that occur. Drivers must understand timing requirements, interrupt handling, DMA setup, and all the low-level details that make each storage technology unique.

At the bottom of the stack sits the actual storage hardware including the storage controller chip that interprets commands and the physical storage media whether magnetic platters or flash memory chips. The controller manages all the mechanical or electronic operations that actually read and write data, implementing complex algorithms for error correction, wear leveling, bad block management, and performance optimization. Modern storage devices are sophisticated computers in their own right with processors, RAM, and firmware running inside them, though these internals are invisible to the operating system which simply sends commands and receives responses.

File Systems: Organizing Chaos Into Order

The file system creates the organized structure of files and folders that you interact with daily from the chaos of millions of individual data blocks. Understanding file systems reveals how the operating system maintains this organization and enables finding your data among vast amounts of storage.

Directory structures create the hierarchical organization of folders containing files and subfolders. Each directory is itself a special file that contains lists of the files and subdirectories it contains along with pointers to where their metadata is stored. When you navigate to a folder in your file manager, the operating system reads the directory file for that folder and displays the entries it contains. The root directory serves as the starting point with all other directories descending from it in a tree structure. This hierarchical organization matches how people naturally categorize information and makes finding specific files manageable even when storage contains millions of files.

File metadata stored separately from file content includes the file name, size, creation and modification dates, permissions controlling who can access the file, and most critically the addresses of data blocks where the file’s actual content is stored. Different file systems organize this metadata differently. Unix-like file systems use inodes which are fixed-size data structures containing file metadata with the file name stored in directories that point to inodes. NTFS on Windows uses a Master File Table where each entry describes one file including its metadata and data locations. APFS on macOS uses B-trees for organizing metadata flexibly. Despite these implementation differences, all file systems must track the same essential information linking file names to their data and metadata.

Block allocation strategies determine how file systems assign disk blocks to files. Contiguous allocation places all of a file’s blocks consecutively, providing excellent performance for sequential access because reading the file requires no seeking, but this approach creates fragmentation problems as files are created and deleted leaving gaps that cannot fit new files. Linked allocation stores a pointer in each block indicating where the next block is located, allowing files to use any available blocks regardless of location but making random access slow because finding a specific position requires following the chain from the beginning. Extent-based allocation used by modern file systems allocates groups of contiguous blocks called extents to files, recording the starting block and length of each extent. This combines the sequential access performance of contiguous allocation with the flexibility of scattered allocation by minimizing the number of separate fragments.

Journaling provides crash recovery by maintaining a log of pending changes before committing them to the main file system structures. Before modifying critical metadata, the file system writes the intended changes to the journal, then performs the actual modifications, then marks the journal entries complete. If the system crashes mid-operation, the journal can be replayed during the next boot to complete interrupted operations or undo partial changes, ensuring file system consistency rather than leaving corrupted structures. This transactional approach prevents crashes during write operations from causing data loss or file system corruption, dramatically improving reliability.

Free space management tracks which blocks are available for allocation to new files. Bitmaps use one bit per block with zero indicating free and one indicating allocated, enabling fast determination of free blocks but consuming memory proportional to total storage capacity. Free lists chain together free blocks in linked lists, using minimal memory but making allocation slower. Modern file systems use sophisticated data structures like B-trees that balance fast allocation, low memory overhead, and efficient space utilization.

Device Drivers: Speaking the Hardware’s Language

Device drivers form the critical translation layer between the operating system’s generic block device interface and the specific protocols that different storage hardware requires. Understanding drivers reveals how the operating system adapts to diverse storage technologies.

The driver’s primary responsibility is translating block read and write operations into the command sequences that the storage controller understands. When the block layer requests reading a specific block, the driver constructs the appropriate read command for its hardware type, specifies the block address using whatever addressing scheme the hardware requires, sets up DMA transfers so data can flow directly between the storage device and memory without processor involvement, and sends the command to the hardware. The driver then waits for the operation to complete, typically by handling an interrupt that the controller generates when the operation finishes, then returns the results to the block layer.

SATA drivers communicate with Serial ATA hard drives and SSDs using the Advanced Host Controller Interface (AHCI) or the newer NVMe Host Controller Interface for NVMe SSDs. SATA uses a command protocol where the driver writes commands to specific memory-mapped registers that the SATA controller monitors, waits for the controller to signal command completion through interrupts, and reads results from other registers. NVMe uses a completely different queue-based interface optimized for high-performance SSDs where commands are placed in submission queues and completions are reported in completion queues, enabling much higher command rates than SATA’s simpler interface.

USB storage drivers implement the USB Mass Storage protocol which makes USB drives appear as SCSI devices regardless of their internal technology. This clever abstraction means the same driver and software stack can work with any USB storage device whether flash drives, external hard drives, or card readers. The USB storage driver communicates over the USB bus using the USB protocols, but presents a SCSI interface to higher layers, showing how drivers can create additional abstraction layers when needed.

Error handling in drivers becomes critical because storage operations can fail for many reasons including device failures, transmission errors, or timeout conditions. The driver must detect these errors from whatever signals the hardware provides, determine whether retrying the operation might succeed, implement appropriate retry logic with backoff to avoid overwhelming failing devices, and ultimately report permanent failures to higher layers when retries are exhausted. Good error handling distinguishes reliable drivers from problematic ones because poor error handling can cause data loss or system hangs when storage devices misbehave.

Initialization and device discovery happen when the system boots or devices are hot-plugged. The driver must probe for devices on its bus, identify what devices are present through device identification protocols, allocate resources like interrupt lines and DMA channels, configure the hardware to operational states, and register the devices with the block layer so they become available to the file system. This initialization must handle devices that are not present gracefully, configure devices that are present correctly, and enable hot-plugging where devices can be added or removed while the system runs.

Physical Communication: Buses and Interfaces

Data must physically travel between the processor, memory, and storage devices through buses that provide the electrical pathways and protocols for communication. Understanding these interfaces reveals the limitations and capabilities of different storage connection methods.

SATA, or Serial ATA, replaced the older parallel ATA interface and remains common for connecting hard drives and SATA SSDs. SATA uses serial communication where data travels one bit at a time over a pair of differential signal wires, with separate wires for transmitting and receiving enabling simultaneous bidirectional communication. SATA III, the current version, provides up to 600 megabytes per second transfer rate which is adequate for hard drives but increasingly limiting for fast SSDs. SATA cables connect the storage device directly to a SATA controller on the motherboard or in an expansion card, with each device requiring its own cable and SATA port.

NVMe, or Non-Volatile Memory Express, is a modern interface designed specifically for solid-state drives that connects directly to PCI Express lanes rather than going through SATA controllers. NVMe SSDs can achieve transfer rates of several gigabytes per second because they use multiple PCI Express lanes in parallel and because the NVMe protocol is optimized for the low latency and high parallelism that flash memory provides. The direct PCIe connection eliminates the SATA interface overhead and the NVMe protocol uses efficient queue-based communication rather than legacy command protocols designed for mechanical hard drives. Modern high-performance systems increasingly use NVMe SSDs for operating system and application storage due to these substantial performance advantages.

USB provides a universal interface that works with many device types including storage devices. USB storage communication happens through the USB protocol stack which handles device enumeration, power management, and data transfer over USB cables that can be several meters long. USB transfer rates have increased through successive versions with USB 3.2 and USB4 providing multi-gigabit speeds competitive with SATA for external storage. The convenience of USB for external storage makes it extremely popular despite being somewhat slower than internal interfaces for equivalent storage technology.

Thunderbolt combines PCI Express lanes and DisplayPort signals in a single cable, providing very high bandwidth for external devices. Thunderbolt 3 and 4 use the same USB-C physical connector as USB but provide up to 40 gigabits per second of bandwidth, making external Thunderbolt storage competitive with internal NVMe drives. The high cost of Thunderbolt controllers limits it to professional applications and high-end systems, but it demonstrates how interface technology continues advancing to keep up with storage device capabilities.

Read and Write Operations: The Journey of Data

Following a read or write operation from application request through all the layers to physical storage and back reveals the complete communication process and all the transformations data undergoes.

When an application wants to read data, it calls a read function specifying which file to read from and how many bytes to retrieve. This request enters the file system layer which determines which blocks of the file contain the requested data. The file system consults its metadata structures to find the disk block addresses corresponding to the requested file position and issues block read requests for those blocks. These requests might already be satisfied by cached data in memory from previous reads, in which case the file system immediately returns the cached data without involving lower layers at all. This caching is crucial for performance because reading from memory is thousands of times faster than reading from storage devices.

If the needed blocks are not cached, the block layer receives the read requests and adds them to its queue of pending operations. The I/O scheduler in the block layer may reorder these requests to optimize access patterns, batching multiple requests that access nearby blocks or reordering them to minimize seeking on hard drives. For SSDs, the scheduler might use simpler algorithms since SSDs have no seek time penalty, though it still batches operations to reduce overhead. The scheduler eventually dispatches optimized request sequences to the device driver.

The device driver translates the block read requests into hardware-specific commands. For a SATA drive, the driver programs DMA to transfer data from the drive to a memory buffer, writes the read command and block address to the drive controller’s registers, and waits for an interrupt signaling completion. For an NVMe drive, the driver constructs a read command in the submission queue describing the blocks to read and where to put the data, rings a doorbell register to notify the drive of the new command, and polls or waits for an interrupt when the completion queue receives the finished command.

The storage controller inside the drive receives the command and performs the physical read operation. In a hard drive, this involves positioning the read head over the correct track, waiting for the platter to rotate until the desired sector passes under the head, reading the magnetic patterns as the sector passes and converting them to digital data, applying error correction to detect and correct any errors, and transferring the resulting data through the SATA interface. In an SSD, the controller reads the specified flash memory pages using the flash memory’s page read command, applies error correction, and transfers the data through the NVMe interface. The differences in these operations explain why SSDs are so much faster than hard drives—the SSD has no mechanical movement and can access any location equally quickly.

The data travels back up through the layers in reverse with the driver copying the received data into the memory buffer the block layer specified, the block layer updating its cache with the newly read data and satisfying the waiting request, and the file system extracting the relevant bytes from the disk blocks and returning them to the application. Throughout this entire process, error checking occurs at multiple levels to ensure data integrity with the storage controller applying error correction, the driver checking for transmission errors, and the file system validating metadata consistency.

Write operations follow a similar path but with additional complexity around ensuring data integrity and handling write ordering. The file system must sometimes write metadata before or after data blocks to maintain consistency, the block layer must handle cache coherency to ensure writes eventually reach persistent storage, and the device driver must confirm that writes committed successfully before reporting completion. Modern storage devices often cache writes internally to improve performance, but the operating system must be able to flush these caches when durability is required, such as after database transactions commit.

Performance Optimization: Making Storage Fast

The operating system employs numerous optimization techniques to minimize the performance impact of storage being much slower than processors and memory, and these optimizations significantly affect how communication happens.

Read-ahead or prefetching anticipates future read requests based on current access patterns. When the file system detects sequential reading, it begins reading subsequent blocks before they are explicitly requested, placing them in cache where they will be immediately available when the application asks for them. This hides storage latency by ensuring data is ready before it is needed. The operating system must predict correctly which data will be needed next, avoiding wasteful prefetching of data that goes unused, and it monitors prediction accuracy to adjust prefetch aggressiveness.

Write-back caching allows write operations to complete immediately by storing written data in memory cache without immediately writing to the storage device. The data is marked dirty in the cache and is written to the device later during idle time or when cache pressure forces eviction of dirty blocks. This batching of writes improves performance by allowing multiple writes to the same location to be combined into single physical writes, enabling the I/O scheduler to optimize write ordering, and allowing the application to continue working without waiting for slow storage operations. However, write-back caching risks data loss if power fails before cached writes reach persistent storage, so critical operations use explicit flush commands to force writing cached data.

I/O scheduling reorders operations to optimize access patterns and share storage bandwidth fairly among competing requesters. For hard drives, elevator algorithms minimize mechanical seeking by servicing requests in physical location order rather than arrival order. For SSDs, schedulers focus on fairness and priority management since SSDs have no seek time to optimize. The deadline scheduler ensures no request waits indefinitely by imposing maximum time limits before requests must be serviced. These scheduling algorithms significantly affect both throughput and latency for storage operations.

Caching at multiple levels stores frequently accessed data in progressively faster storage tiers. The file system maintains a page cache in main memory holding recently accessed file data. The storage controller inside drives maintains its own cache using on-board RAM to buffer frequently accessed data and pending write operations. Some systems use intermediate solid-state storage as a cache tier between main memory and traditional hard drives. This hierarchical caching exploits temporal locality where recently accessed data is likely to be accessed again soon, dramatically reducing effective storage latency for cached data.

Native Command Queuing and Tagged Command Queuing allow storage devices to process multiple commands simultaneously rather than one at a time. The device can optimize the order it processes queued commands based on its internal knowledge of physical layout and current position, achieving better performance than the operating system could achieve by submitting one command at a time. NVMe extends this concept to extreme levels with thousands of possible queued commands, enabling very high-performance parallel I/O.

Understanding how operating systems communicate with storage devices reveals the sophisticated multi-layered architecture that makes reliable data storage possible. From the high-level file system abstractions that present organized hierarchies of named files through the device drivers that speak each storage technology’s unique language to the physical interfaces and protocols that move data across buses, every layer provides essential services that enable the seamless storage experience you depend on. The next time you save a file, appreciate the remarkable journey your data takes through all these layers, ultimately becoming patterns of magnetism or electrical charges that preserve your work until you need it again, regardless of whether your storage is a traditional hard drive or a modern solid-state drive.