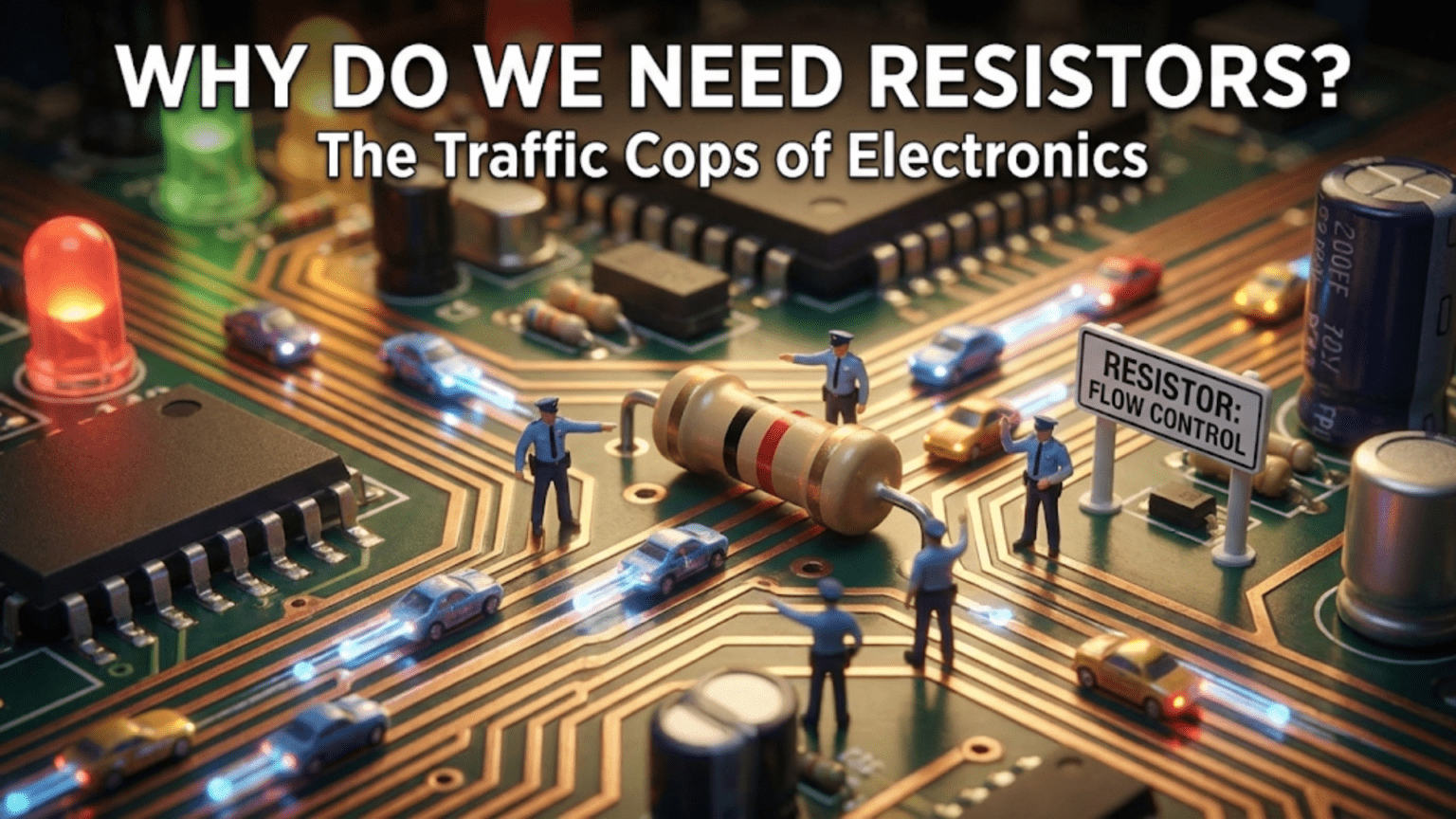

Introduction

If you examine the circuit board inside any electronic device—whether a simple calculator, a smartphone, or a sophisticated computer—you will find resistors everywhere. These humble components, often appearing as small cylindrical parts with colored bands, outnumber nearly every other component type in typical circuits. A single circuit board might contain hundreds or even thousands of resistors, each performing a specific function essential to circuit operation. Yet for beginners learning electronics, resistors often seem mysterious. Why do circuits need so many resistors? What exactly do these simple components accomplish that makes them so indispensable?

Resistors perform a remarkable variety of functions despite their fundamental simplicity. At the most basic level, resistors oppose current flow, converting electrical energy into heat through a process described by Ohm’s Law. This seemingly simple characteristic enables resistors to control current levels, divide voltages, protect sensitive components, bias transistors, filter signals, measure currents, set timing, and perform countless other essential functions. No other component appears in as many different circuit roles as the resistor.

Understanding why we need resistors and what they accomplish provides foundational knowledge for all electronics work. When you can explain why a particular circuit includes a specific resistor, you demonstrate genuine circuit comprehension rather than merely following instructions. When you can select appropriate resistor values for new designs, you have progressed from circuit consumer to circuit creator. This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of resistor functions from fundamental principles, developing intuition for recognizing resistor roles in real circuits and selecting appropriate values for your own designs.

The Fundamental Function: Controlling Current

At its core, every resistor performs one fundamental function: it opposes the flow of electrical current in a controlled, predictable manner. This opposition, quantified as resistance and measured in ohms, determines how much current flows for any given voltage according to Ohm’s Law (I = V / R). This simple relationship underlies every resistor application.

Current Limiting: Protecting Vulnerable Components

Perhaps the most essential resistor function is current limiting—preventing excessive current from flowing through components that would be damaged by overcurrent conditions. Many electronic components have strict maximum current ratings that must not be exceeded. LEDs, for example, have very low forward voltage drops (typically 2-3 volts) and will draw excessive current if connected directly to higher voltage sources. Without current limiting, an LED connected to a 9-volt battery would attempt to draw far more than its rated current, overheating and destroying itself within seconds.

A current-limiting resistor placed in series with the LED solves this problem elegantly. The resistor and LED together form a voltage divider, with the resistor dropping the excess voltage that the LED cannot handle. By selecting the resistor value appropriately, we can set the LED current to any desired value within its safe operating range. A typical calculation might proceed as follows: if we have a 9-volt supply, an LED that drops 2 volts and should operate at 20 milliamps, we need to drop 7 volts across the resistor at 20 milliamps, giving us R = V / I = 7V / 0.02A = 350 ohms.

This same current-limiting principle protects countless other components. Transistor bases require current limiting to prevent excessive base current. Integrated circuit inputs often need current limiting when driven from higher-voltage sources. Charging circuits use current-limiting resistors to control charging rates. The ubiquity of current limiting explains why circuits contain so many resistors—virtually every active component requires some form of current control.

Current Setting: Establishing Operating Points

Beyond simply preventing overcurrent damage, resistors often establish precise operating currents that determine device behavior. Transistor amplifiers require specific bias currents to position the transistor in its optimal operating region. Voltage references need precise current levels to maintain accurate output voltages. Sensor circuits often convert measured physical quantities to currents that must be precisely controlled.

Consider a simple transistor amplifier. The transistor’s operating characteristics depend critically on the base current and collector current. Resistors in the bias network establish these currents at specific values that center the transistor in its active region, maximizing available signal swing and minimizing distortion. Changing these resistor values shifts the operating point, potentially improving some performance aspects while degrading others. The designer selects resistor values to achieve the optimal tradeoff for the application.

Similarly, current mirrors in analog integrated circuits use transistor-resistor combinations to precisely copy current from one circuit branch to another. The resistor sets the reference current, and the transistor arrangement replicates this current wherever needed. This current-setting function enables sophisticated analog circuits to operate with tight performance specifications despite manufacturing variations in transistor characteristics.

Current Sensing: Measuring Flow Indirectly

Resistors enable current measurement through an elegant application of Ohm’s Law. By placing a known resistance in series with the current to be measured and measuring the voltage across that resistance, we can calculate current precisely (I = V / R). This technique, called current sensing or current shunting, appears in applications from battery monitoring to motor control to power supply protection.

The ideal current-sensing resistor has very low resistance to minimize power loss and voltage drop while still developing measurable voltage at the currents of interest. For measuring amperes, resistors with resistances of 0.01 to 0.1 ohms are common. At 10 amps through a 0.01-ohm resistor, the voltage drop is only 0.1 volts (V = I × R = 10A × 0.01Ω = 0.1V), but this is sufficient for accurate measurement with appropriate amplification.

Current sensing finds applications in battery management systems that monitor charging and discharging currents, motor controllers that implement current limiting for overload protection, and power supplies that regulate output current. The simplicity and reliability of resistor-based current sensing makes it a preferred approach in many designs, though high-current applications may use alternative techniques to minimize power loss.

Voltage Division: Creating Reference Levels

Voltage division represents another fundamental and ubiquitous resistor function. By placing two or more resistors in series across a voltage source, we create intermediate voltages at the junctions between resistors. This simple technique enables countless applications.

Providing Bias Voltages

Analog circuits frequently require specific bias voltages at various nodes to establish proper operating points for transistors and other active devices. Rather than using multiple power supplies to provide these different voltages, resistive voltage dividers create them from a single supply. Two resistors in series across the power supply create a junction voltage determined by the resistor ratio: V_out = V_in × (R2 / (R1 + R2)).

This voltage divider equation enables precise voltage setting through resistor selection. Need exactly 2.5 volts from a 5-volt supply? Use equal-value resistors. Need 3.3 volts from 5 volts? Use a ratio of approximately 2:1 (for example, 2kΩ and 4kΩ). The flexibility of voltage division through resistor selection makes it an indispensable circuit design technique.

However, voltage dividers have an important limitation: they work best when the load draws minimal current compared to the current flowing through the divider resistors themselves. Heavy loading causes the output voltage to drop because the load current flows through the lower resistor, creating additional voltage drop. Designers account for this by using low divider resistances (high divider current) relative to expected load current, accepting the higher power consumption in the divider to maintain voltage regulation.

Signal Attenuation and Level Shifting

When signals have amplitudes too large for subsequent circuit stages, resistive dividers attenuate them to appropriate levels. An audio preamplifier might produce 10-volt peak-to-peak signals, but the following stage might require only 1-volt inputs. A 10:1 voltage divider (for example, 9kΩ and 1kΩ) reduces the signal to the appropriate level.

Similarly, when interfacing circuits operating at different logic levels (say, 5-volt logic driving 3.3-volt logic inputs), resistive dividers shift signal levels to compatible ranges. While dedicated level-shifting integrated circuits offer superior performance for high-speed signals, simple resistive dividers suffice for many applications and cost almost nothing.

Oscilloscope probes use precision voltage dividers to extend measurement range. A 10× probe contains a 9:1 divider (9MΩ in the probe, 1MΩ in the oscilloscope) that reduces signal amplitude by a factor of ten, allowing measurement of higher voltages than the oscilloscope could otherwise handle. The divider also reduces capacitive loading on the circuit being measured, minimizing measurement interference.

Reference Voltage Generation

Simple voltage references use resistive dividers to create stable voltage references from more stable higher-voltage sources. While precision voltage references use sophisticated circuits based on bandgap references or zener diodes, simple applications can use resistor dividers to create adequate reference voltages. A comparator threshold might be set using a divider that establishes the reference voltage at which comparison occurs.

The stability of resistor-based voltage references depends on supply voltage stability, resistor tolerance, and resistor temperature coefficients. For applications requiring high accuracy, designers select tight-tolerance resistors with low temperature coefficients and may include temperature compensation or active regulation. For less demanding applications, standard resistors provide adequate reference voltages at minimal cost.

Pull-Up and Pull-Down: Defining Default States

Digital circuits frequently use resistors to establish default logic states for inputs that might be left floating (unconnected) under certain conditions. These pull-up and pull-down resistors ensure predictable circuit behavior even when driving signals are absent.

The Floating Input Problem

Digital logic gates and microcontroller inputs have very high impedance, drawing negligible current from whatever drives them. This high impedance is generally desirable because it means inputs do not load down signal sources. However, it creates a problem when inputs are left unconnected: the high impedance cannot discharge accumulated charge or resist electrical noise, leaving the input voltage undefined. A floating input might randomly read as logic high or logic low, or might oscillate between states as ambient electrical noise influences it.

Floating inputs cause unpredictable circuit behavior, intermittent failures, and difficult-to-diagnose problems. An input that reads high during testing might read low in production, or might read correctly most of the time but occasionally glitch to the wrong state. These intermittent issues are extremely frustrating to troubleshoot because they are not consistently reproducible.

Pull-Up Resistors: Default High

A pull-up resistor connects an input to the positive supply voltage through a high-value resistor (typically 1kΩ to 100kΩ). When nothing actively drives the input low, the pull-up resistor pulls the input to logic high through the resistor. When something does drive the input low (by connecting it to ground), the low impedance of the active driver overcomes the high impedance of the pull-up resistor, pulling the input low despite the resistor’s presence.

The pull-up resistor value represents a tradeoff. Lower resistance pulls the input more strongly to high, making it more noise-immune and allowing faster transitions when the input switches. However, lower resistance draws more current when the input is driven low, wasting power. Higher resistance conserves power but makes the input more susceptible to noise and slower to transition. Typical values range from 1kΩ for high-speed or noisy environments to 100kΩ for low-power applications.

Pull-up resistors commonly appear in button circuits, where a button connects the input to ground when pressed. Without the pull-up resistor, the input would float when the button is not pressed. With the pull-up, the input reliably reads high until button press pulls it low. This simple arrangement requires only a resistor and a button—no additional active components.

Pull-Down Resistors: Default Low

Pull-down resistors perform the complementary function, connecting inputs to ground through a resistor to ensure they read logic low when not actively driven high. Pull-downs are somewhat less common than pull-ups because many circuit configurations naturally work better with pull-ups, but they serve the same essential function of defining default input states.

The same tradeoff between resistance value, power consumption, noise immunity, and speed applies to pull-down resistors as to pull-ups. The specific value chosen depends on application requirements and the characteristics of the driving circuitry.

Internal Pull-Ups and Pull-Downs

Many microcontrollers and other integrated circuits include optional internal pull-up or pull-down resistors that can be enabled through software configuration. These internal resistors eliminate the need for external resistors in many applications, simplifying circuit design and reducing component count. However, internal pull resistors typically have higher resistance (often 20kΩ to 50kΩ) than optimal external resistors, so external resistors are still used when lower resistance is needed for noise immunity or switching speed.

Impedance Matching and Termination

In high-frequency circuits and transmission line applications, resistors perform crucial impedance matching and termination functions that ensure signal integrity and prevent reflections.

Transmission Line Basics

When signals travel through wires at frequencies where wire length becomes significant compared to signal wavelength, the wires behave as transmission lines with characteristic impedance. Signals reflect from impedance mismatches at transmission line ends or at discontinuities along the line. These reflections cause signal distortion, ringing, and potential logic errors in digital systems or signal corruption in analog systems.

A transmission line’s characteristic impedance depends on its geometry and the dielectric materials surrounding the conductors. Common characteristic impedances include 50 ohms for RF coaxial cables, 75 ohms for video cables, and various values (often 85-100 ohms) for PCB traces depending on trace geometry and layer stackup.

Termination Resistors

Termination resistors placed at transmission line ends match the line’s characteristic impedance, absorbing signal energy and preventing reflections. The termination resistor value should equal the characteristic impedance. A 50-ohm transmission line requires a 50-ohm termination resistor at its end. When the signal reaches this resistor, it dissipates in the resistor rather than reflecting back down the line.

Series termination places a resistor in series with the signal source, with the resistor value chosen such that the source impedance plus series resistor equals the characteristic impedance. This technique works well for point-to-point connections and consumes no DC power. Parallel termination connects a resistor between signal and ground (or between signal and supply) at the line end, matching the characteristic impedance directly but consuming DC power when the signal is not at the termination voltage.

Impedance Matching for Power Transfer

In RF and communication circuits, impedance matching maximizes power transfer from source to load. Maximum power transfer occurs when load impedance equals source impedance (or its complex conjugate for reactive impedances). Resistive networks often implement these impedance transformations, though transformers, LC networks, and transmission line stubs also perform matching functions.

Understanding when impedance matching matters and when termination is required saves unnecessary complexity in circuits where these techniques are not needed. Low-frequency digital signals on short PCB traces typically do not require termination. Audio signals below 20kHz traveling short distances do not need impedance matching. But high-speed digital signals, video signals, and RF signals absolutely require proper termination and matching for reliable operation.

Timing and Frequency Control

Resistors combine with capacitors and inductors to create time constants and frequency-dependent behavior essential to countless circuit functions.

RC Time Constants

When a resistor and capacitor connect in series, they create an RC circuit with a time constant τ (tau) equal to the product of resistance and capacitance: τ = R × C. This time constant characterizes how quickly the circuit responds to voltage changes. After one time constant, the capacitor voltage has changed by approximately 63% of the total change it will eventually undergo. After five time constants, the capacitor has reached about 99% of its final value.

RC time constants determine charging and discharging rates for capacitors, enabling timing functions throughout electronics. A simple timing circuit might charge a capacitor through a resistor until the capacitor voltage reaches a threshold that triggers some action. By selecting appropriate resistor and capacitor values, designers set precise timing intervals from microseconds to hours.

555 timer circuits use RC networks to establish oscillation frequency or pulse duration. The resistor values directly determine these timing parameters according to well-established formulas. Changing resistor values changes timing proportionally, making frequency or pulse width adjustment straightforward.

Filters: Frequency-Dependent Voltage Division

Resistors and capacitors combine to create filters that pass certain frequencies while attenuating others. A simple RC low-pass filter consists of a resistor in series with a capacitor to ground. At low frequencies where capacitive reactance is high, the capacitor barely loads the resistor, passing signals with little attenuation. At high frequencies where capacitive reactance is low, the capacitor increasingly shunts signal to ground, attenuating high-frequency components.

The cutoff frequency, where attenuation reaches -3dB (approximately 70% of the input amplitude), occurs at f_c = 1 / (2πRC). Resistor and capacitor values can be selected to achieve desired cutoff frequencies from millihertz to megahertz. High-pass filters use similar arrangements with component positions swapped, passing high frequencies while attenuating low frequencies.

More sophisticated filters use multiple RC sections, RL combinations (resistor-inductor), or RLC networks (resistor-inductor-capacitor) to achieve sharper rolloff or more complex frequency response shapes. Active filters add amplifiers to RC networks, achieving filter characteristics impossible with passive components alone. In all these filters, resistors play essential roles in setting filter characteristics and establishing frequency behavior.

Oscillators and Waveform Generation

Oscillator circuits use RC or RL networks in feedback paths to establish oscillation frequency. A Wien bridge oscillator uses two RC networks to determine frequency, with resistor values directly affecting the oscillation frequency. Relaxation oscillators charge and discharge capacitors through resistors, with resistor values determining charging rates and thus oscillation frequency.

Waveform-shaping circuits use resistor-capacitor combinations to convert square waves to ramps, create exponential waveforms, or synthesize complex shapes from simple inputs. These waveshaping applications are essential in function generators, synthesizers, and control systems requiring specific temporal response characteristics.

Transistor Biasing: Setting Operating Points

Transistor circuits require careful biasing to establish proper operating points, and resistors provide the primary means for accomplishing this biasing.

Bipolar Transistor Biasing

Bipolar junction transistors need base current to establish collector current according to the transistor’s current gain (β or hFE). Resistors in the base circuit set this base current. A simple approach uses a resistor from the power supply to the base, setting base current through the resistor based on supply voltage and the base-emitter junction voltage drop.

However, this simple biasing is temperature-sensitive and varies with transistor gain. More sophisticated biasing networks use multiple resistors to create voltage dividers that establish base voltage, emitter resistors that provide negative feedback stabilizing the operating point, and collector resistors that set collector current and voltage swing. These resistor networks ensure reliable transistor operation despite temperature variations and transistor-to-transistor differences.

The ratios between these resistor values determine critical amplifier characteristics including gain, input impedance, output impedance, and frequency response. Designers select resistor values through calculations that balance competing requirements, often iterating through several designs before achieving optimal performance.

MOSFET Biasing

MOSFETs require gate voltage relative to source to establish channel conductivity, but they draw virtually no gate current. This simplifies some biasing aspects while complicating others. Gate bias resistors can be very high values (often megohms) because no significant gate current flows. These high resistances minimize power consumption but make circuits more susceptible to electrical noise and static electricity.

Source resistors provide negative feedback that stabilizes MOSFET operating points against temperature variations and device differences. Drain resistors set drain current and voltage swing, determining amplifier gain and signal handling capability. The specific resistor values chosen depend on desired operating characteristics and the particular MOSFET being used.

Feedback and Gain Control

Resistors in amplifier feedback paths determine closed-loop gain and frequency response. An inverting operational amplifier’s gain equals the ratio of feedback resistor to input resistor: A_v = -R_f / R_in. Want a gain of -10? Use a feedback resistor ten times larger than the input resistor. Want gain of -100? Use a 100:1 ratio. This precise gain control through resistor selection makes operational amplifiers extraordinarily versatile.

Frequency response shaping often uses frequency-dependent feedback networks where capacitors in series or parallel with feedback resistors change feedback impedance with frequency. Low-pass, high-pass, and band-pass amplifiers all use resistor-capacitor combinations in feedback paths to achieve desired frequency characteristics.

Power Dissipation and Voltage Dropping

Sometimes resistors serve primarily to dissipate power or drop voltage to waste levels that simpler regulation techniques can handle.

Ballast Resistors

Ballast resistors limit current to devices with negative resistance characteristics that would otherwise operate unstably. Certain discharge lamps, tunnel diodes, and other devices exhibit regions where increasing voltage causes decreasing current—a negative resistance that can lead to oscillation or destruction without ballasting.

The ballast resistor introduces positive resistance in series with the negative resistance device, ensuring net positive resistance that maintains stable operation. The resistor value must be large enough to overcome the negative resistance while remaining small enough to allow desired operating current.

Dummy Loads

Power supply testing and troubleshooting often requires loads that dissipate specific power levels. Resistors serve as dummy loads, converting electrical power to heat in controlled, predictable ways. A 10-watt resistor can dissipate 10 watts continuously, providing a known load for power supply testing.

High-power resistors used as dummy loads can dissipate hundreds or thousands of watts, requiring substantial heat sinking and cooling. These resistors often use special constructions including wirewound elements on ceramic cores with large finned heat sinks. The predictable, linear characteristics of resistive loads make them valuable for testing power supplies and amplifiers.

Voltage Dropping for Simple Regulation

When precise voltage regulation is unnecessary and efficiency is not critical, resistors can drop excess voltage to achieve approximate regulation. Adding a resistor in series with a load drops voltage proportional to current, providing crude regulation if load current remains relatively constant. This technique, called resistance regulation, is simple and inexpensive but inefficient because all the dropped voltage times current is dissipated as heat in the resistor.

Series resistance commonly appears in LED drive circuits, low-power circuits, and applications where efficiency is less important than simplicity. More efficient approaches like switching regulators are preferred when power levels are significant or battery life is important.

Protection Functions

Resistors protect circuits and components through current limiting and voltage division, preventing damage from overvoltage, overcurrent, or electrostatic discharge.

Electrostatic Discharge Protection

Human bodies can accumulate thousands of volts of static electricity. Touching circuit inputs with statically charged fingers can deliver high-voltage pulses that destroy sensitive semiconductor junctions. Series resistors at inputs limit current from ESD events, often working with protection diodes that clamp voltage to safe levels. The resistor limits current through the protection diodes, preventing the diodes from being destroyed while they protect the input.

ESD protection resistors typically range from a few hundred to several thousand ohms, large enough to limit current effectively but small enough not to interfere with normal signal transmission. Modern integrated circuits often include internal ESD protection, but external resistors provide additional protection in demanding environments or for particularly sensitive inputs.

Inrush Current Limiting

When power is first applied to circuits containing large capacitors, the uncharged capacitors appear as short circuits, potentially drawing enormous inrush current that can damage components or blow fuses. Series resistors limit this inrush current to safe levels, allowing capacitors to charge gradually rather than demanding instantaneous current delivery.

The inrush-limiting resistor must be large enough to limit initial current but small enough not to cause excessive voltage drop during normal operation. Sometimes thermistors replace fixed resistors in inrush limiting applications—the thermistor has high resistance when cold (limiting inrush), but heats from current flow and decreases resistance to minimize voltage drop during normal operation.

Fusing Resistors

Certain resistors are designed to act as fuses, opening (becoming very high resistance or open circuit) when excessive current flows through them. These fusible resistors combine current-sensing and overcurrent protection in a single component. When fault current exceeds design limits, the resistor element vaporizes or breaks, opening the circuit and preventing damage to downstream components.

Fusible resistors find applications in power supplies, motor drives, and other circuits where component failures might cause dangerous overcurrent conditions. They provide a cheap, simple protection mechanism, though they must be replaced after operation unlike resettable circuit breakers.

Measurement and Calibration

Resistors enable measurement of various electrical quantities and provide calibration references for instruments and control systems.

Shunt Resistors for Current Measurement

As discussed earlier, low-value precision resistors enable accurate current measurement through voltage drop measurement. The shunt resistor must have precisely known resistance, typically with tolerance of 1% or better, and should have low temperature coefficient to maintain accuracy over temperature ranges.

Current shunt resistors often use four-terminal construction: two terminals carry current, while two separate terminals sense voltage. This four-wire measurement eliminates voltage drop in current-carrying connections from the measurement, ensuring accuracy even when measuring large currents where connection resistance might be significant.

Bridge Circuits for Precise Measurement

Wheatstone bridges use four resistors arranged in a diamond configuration to measure unknown resistance with high precision. Three resistors of known value combine with one unknown resistor, and the bridge is balanced by adjusting one known resistor until voltage between opposite corners of the diamond goes to zero. At balance, the unknown resistance can be calculated from the known resistances.

Similar bridge configurations measure capacitance, inductance, impedance, and various physical quantities that transduce to resistance changes (temperature, strain, pressure, etc.). The precision and sensitivity of bridge circuits make them valuable for instrumentation and measurement applications.

Calibration and Reference

Precision resistors serve as references for calibrating instruments and establishing known resistance values for testing. Standard resistors with tolerances of 0.01% or better provide traceable references for calibrating ohmmeters and other resistance measurement instruments. Arrays of precision resistors set gain, offset, and other calibration parameters in analog-to-digital converters, instrumentation amplifiers, and precision measurement systems.

The stability and predictability of precision resistors make them superior references compared to electronic components whose characteristics might drift over time or vary with temperature. Critical measurement and control systems rely on precision resistor networks to maintain accuracy over years of operation.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Component

Resistors are indispensable because they perform an extraordinary variety of essential functions throughout electronics. They limit current to protect vulnerable components, divide voltage to create reference levels, define default logic states through pull-up and pull-down configurations, match impedances for signal integrity, set timing through RC networks, bias transistors for proper operation, dissipate power, protect against ESD and inrush, enable measurement, and provide calibration references. No other single component type serves so many different purposes across such diverse applications.

The humble resistor, despite its apparent simplicity, is actually one of the most versatile components in the electronics toolkit. Its predictable, linear behavior characterized by Ohm’s Law makes it reliable and easy to apply, while its availability in a vast range of values, tolerances, temperature coefficients, and power ratings makes it adaptable to virtually any requirement. The low cost of resistors encourages their liberal use, and their high reliability ensures long-term circuit operation.

Understanding why we need resistors and recognizing the various roles they play develops circuit comprehension that goes far beyond component identification. When you see a resistor in a schematic, you should be able to deduce its function from its position and value. Is it limiting current to an LED? Creating a bias voltage for a transistor? Pulling an input to a defined state? Setting an RC time constant? Providing ESD protection? Each resistor exists for a reason, and understanding that reason provides insight into circuit operation and design intent.

As you progress in electronics, you will develop intuition for appropriate resistor values in different applications. Current-limiting resistors for standard LEDs typically range from hundreds to thousands of ohms. Pull-up resistors commonly fall between 1kΩ and 100kΩ. RC timing networks might use anything from hundreds of ohms to megohms depending on capacitor values and desired time constants. Bias resistors in transistor circuits typically range from kilohms to hundreds of kilohms. This developing sense of typical values helps you spot errors in schematics and design circuits correctly the first time.

The next time you examine a circuit and see numerous resistors, appreciate that each one is performing a specific, necessary function that enables proper circuit operation. These “traffic cops” of electronics control current flow, establish voltage levels, set timing, define states, protect components, and enable countless other functions. Without resistors, modern electronics would be impossible. Understanding them thoroughly is essential for anyone serious about mastering electronics.