Introduction

Batteries appear in an bewildering variety of voltages from tiny one point five volt button cells powering watches through nine volt batteries in smoke detectors to twelve volt automotive batteries starting cars, with each voltage serving specific purposes determined by the chemical reactions generating electricity, the circuits being powered, and practical considerations of size, cost, and available energy storage. Understanding why different voltages exist, what determines a battery’s voltage, how voltage relates to other battery characteristics, and how to select appropriate voltages for applications transforms battery selection from guesswork into informed decision-making that ensures circuits receive adequate power while avoiding damage from excessive voltage or premature depletion from inadequate capacity.

For beginners encountering batteries in electronics projects, the voltage rating printed prominently on every battery represents one of the most important specifications, yet its significance and the reasons for the specific values often remain unclear. Why are common batteries rated at one point five volts, three volts, nine volts, or twelve volts rather than convenient round numbers like one volt, five volts, or ten volts? Why can’t you use any voltage battery in any device? Why do some devices specify exact battery types while others work with a range of voltages? Understanding these questions requires understanding what voltage means in the context of batteries, how chemical reactions determine voltage, and how circuits are designed to work with specific voltage ranges.

The voltage a battery produces is fundamentally determined by the chemistry of the electrochemical reactions occurring inside it, with each chemical combination producing a characteristic voltage per cell that cannot be changed without changing the chemistry itself. A zinc-carbon or alkaline cell produces approximately one point five volts regardless of physical size because the chemical reaction between zinc and manganese dioxide naturally generates this voltage. A lithium-ion cell produces approximately three point seven volts because lithium’s reactivity with the cathode materials used in these batteries creates this potential difference. Multiple cells connected in series add their voltages, enabling construction of batteries with higher voltages—six one point five volt cells in series create nine volts, explaining the internal structure of nine-volt batteries.

The practical implications of battery voltage affect every aspect of electronics design and usage. Circuits designed for specific voltages require batteries delivering those voltages with reasonable tolerance—too low and circuits may not function or deliver reduced performance, too high and components may be damaged or stressed beyond their ratings. The energy stored in batteries depends on both voltage and capacity measured in amp-hours, with total energy in watt-hours equal to voltage times amp-hour capacity. Higher voltage batteries can deliver the same energy at lower current, reducing resistive losses in wiring and enabling more efficient power distribution in applications from flashlights to electric vehicles.

This comprehensive exploration will build your understanding of battery voltages from electrochemical fundamentals through practical battery selection, examining what determines the voltage of different battery chemistries, why cells combine in series and parallel to create multi-cell batteries, how voltage changes during battery discharge and what this means for circuit operation, the relationship between voltage and battery capacity, matching battery voltage to circuit requirements, and practical considerations including safety margins, voltage regulation, and battery replacement. By the end, you will understand battery voltages thoroughly enough to select appropriate batteries for projects, understand why devices specify particular battery types, and make informed decisions about battery substitution and circuit voltage requirements.

What Determines Battery Voltage: Electrochemistry Fundamentals

Understanding why batteries produce the voltages they do requires examining the chemical reactions that generate electrical energy and how different chemical combinations produce different voltages.

Electrochemical Cells and Voltage Generation

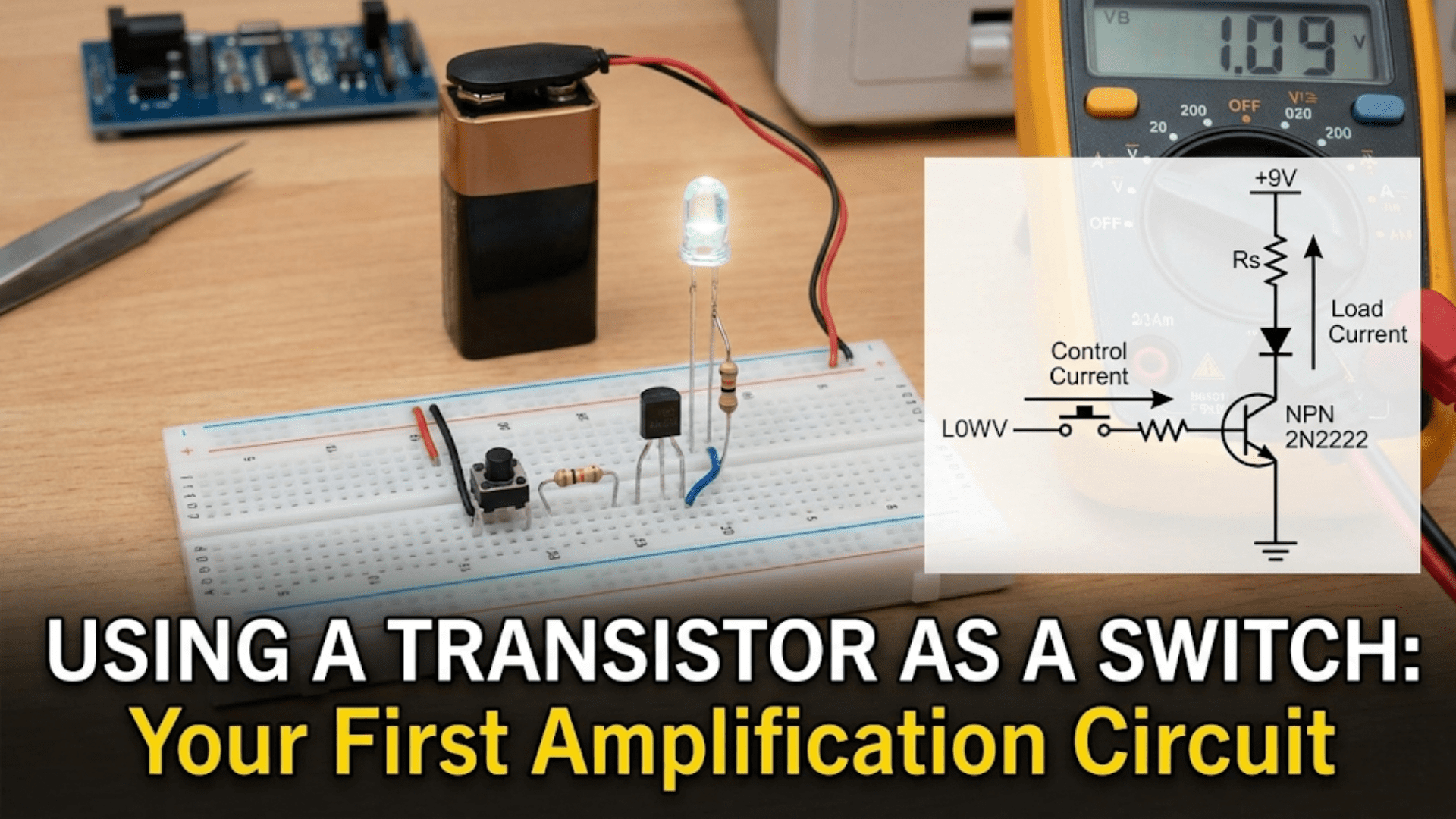

A battery consists of one or more electrochemical cells, each containing two electrodes—an anode and a cathode—immersed in an electrolyte that allows ions to move between electrodes. Chemical reactions at the electrodes transfer electrons from the anode through an external circuit to the cathode, creating electrical current that performs useful work before electrons return to complete the reaction. The voltage across the cell terminals reflects the energy difference between the chemical reaction at the anode and the reaction at the cathode, with this voltage determined entirely by the specific materials used for the electrodes and electrolyte.

The standard electrode potential of each half-cell reaction—measured against a reference hydrogen electrode—indicates how strongly that electrode attracts or releases electrons. The cell voltage equals the difference between the cathode potential and the anode potential, providing a theoretical maximum voltage that actual batteries approach under no-load conditions. For example, zinc metal used as an anode has a standard potential of negative zero point seven six volts, while manganese dioxide used as a cathode in alkaline batteries has a potential around positive zero point eight volts, giving a cell voltage around one point five six volts that matches the nominal one point five volt rating of alkaline batteries.

Different chemical combinations produce different voltages because different materials have different electron affinities and oxidation-reduction potentials. Lead-acid batteries using lead dioxide cathodes and lead anodes with sulfuric acid electrolyte produce approximately two volts per cell because the lead-lead dioxide reaction creates this potential difference. Lithium-ion batteries using lithium cobalt oxide cathodes produce about three point seven volts per cell because lithium’s extreme reactivity creates larger potential differences than less reactive metals like zinc or lead. These voltages are fundamental properties of the chemical systems and cannot be significantly altered without changing the chemistry itself.

Common Battery Chemistries and Their Voltages

Zinc-carbon and alkaline batteries are the most common primary (non-rechargeable) batteries for consumer applications, both producing approximately one point five volts per cell. Zinc-carbon batteries use zinc anodes and carbon rods with manganese dioxide cathodes in an ammonium chloride electrolyte, providing economical power for low-drain applications like remote controls and clocks. Alkaline batteries use similar chemistry but with potassium hydroxide electrolyte, providing better performance under higher drain rates and longer shelf life, making them preferred for flashlights, toys, and higher-drain devices despite slightly higher cost.

Lithium primary batteries use lithium metal anodes with various cathode materials, producing voltages typically around three volts per cell—double the voltage of alkaline cells. The CR2032 coin cell used in computer motherboards and watches exemplifies this chemistry, delivering three volts in a compact package. The higher voltage and excellent energy density make lithium primary cells popular for devices requiring long life in small packages, though higher cost restricts use to applications justifying the premium.

Rechargeable battery chemistries include lead-acid producing two volts per cell and widely used in automotive batteries where six cells in series create twelve-volt systems, nickel-cadmium (NiCd) and nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) both producing approximately one point two volts per cell and commonly packaged as individual cells or multi-cell packs for portable power tools and electronics, and lithium-ion producing three point six to three point seven volts per cell and dominating modern portable electronics from smartphones through laptops to electric vehicles due to excellent energy density and power delivery despite higher cost and more stringent safety requirements.

The voltage differences between chemistries mean they cannot be directly substituted without circuit modifications. Devices designed for alkaline batteries expecting one point five volts per cell might not work properly with NiMH batteries providing only one point two volts per cell, while substituting three-volt lithium batteries for one point five volt alkaline cells would overvolt circuits potentially causing damage. Understanding these voltage differences prevents incorrect substitutions that could damage devices or create safety hazards.

Cell Voltage Versus Battery Voltage

Individual electrochemical cells produce the characteristic voltage of their chemistry—approximately one point five volts for alkaline, three point seven volts for lithium-ion, two volts for lead-acid. However, most batteries used in electronics combine multiple cells to provide higher voltages than single cells produce. These multi-cell batteries connect cells internally in series, adding their voltages to reach desired total voltage. A nine-volt battery contains six one point five volt alkaline cells in series (six times one point five equals nine), a twelve-volt car battery contains six two-volt lead-acid cells in series (six times two equals twelve), and a seven point four volt lithium-ion battery pack contains two three point seven volt cells in series.

The physical construction of multi-cell batteries varies from discrete cylindrical cells connected with internal wiring in nine-volt alkaline batteries through thin flat cells stacked in lithium polymer batteries to individual cell compartments in lead-acid batteries where each cell occupies a section of the battery case. Regardless of physical implementation, the series connection adds voltages while maintaining the current capacity of individual cells—the amp-hour rating of the battery equals the amp-hour rating of one cell even though voltage multiplies by the number of cells.

Understanding that batteries are often series-connected cells explains why common battery voltages are multiples of cell voltages. Nine volts equals six times one point five volts, three volts equals two times one point five volts, six volts equals four times one point five volts, and twelve volts equals eight times one point five volts for alkaline systems or six times two volts for lead-acid. These round multiples simplify design and manufacturing while providing voltage levels suitable for various applications.

How Voltage Changes During Discharge

Battery voltage is not constant but varies during discharge, starting higher when fresh and decreasing as stored energy depletes, with voltage behavior affecting circuit operation and determining when batteries need replacement.

Fresh Battery Voltage and Open-Circuit Voltage

A fresh battery disconnected from any load exhibits open-circuit voltage slightly higher than its nominal rating because no current flows and no voltage drops occur across internal resistance. A fresh alkaline battery might measure one point six volts or higher when new, a nine-volt battery might exceed nine volts, and a fully charged twelve-volt lead-acid battery often measures over twelve point six volts. This higher fresh voltage is normal and expected, representing the maximum voltage the chemistry can deliver without current flow.

When circuits connect to batteries and draw current, the voltage drops below open-circuit voltage due to internal resistance within the battery. This internal resistance, though small—typically tenths to a few ohms for common batteries—causes voltage drops when current flows according to Ohm’s Law. A battery with half an ohm internal resistance delivering one ampere experiences zero point five volt drop across its internal resistance, making terminal voltage half a volt lower than open-circuit voltage. Higher currents cause larger drops, explaining why battery voltage sags significantly when heavy loads connect despite recovering when loads disconnect.

The internal resistance increases as batteries age and discharge, causing voltage under load to decrease more dramatically as batteries deplete. Fresh batteries maintain relatively stable voltage under load, while partially depleted batteries show significant voltage drop when loads connect. This behavior affects circuit operation because circuits sensitive to voltage variations may function poorly with depleted batteries despite those batteries still containing stored energy accessible at lower current drains.

Discharge Curves and Voltage Decline

As batteries discharge and chemical reactants deplete, the voltage gradually decreases from initial high values toward lower end-of-life values. Discharge curves plotting voltage versus time or versus percentage of capacity used show how voltage evolves during use, with curve shape varying across chemistries. Alkaline batteries exhibit relatively gradual voltage decline from one point five volts down to about zero point eight volts at end of life, with voltage remaining above one point two volts for much of the discharge cycle. This gradual decline means devices designed for one point five volts continue operating reasonably well even as batteries partially deplete.

Lithium-ion batteries maintain relatively flat voltage during most of their discharge, staying near three point seven volts until nearly depleted, then dropping rapidly toward three volts at complete discharge. This flat discharge curve provides consistent performance throughout most of the battery’s capacity, with devices experiencing little voltage variation until the battery approaches empty. However, the rapid voltage drop near end of discharge requires protection circuits preventing over-discharge that could damage lithium cells, making lithium battery management more complex than alkaline chemistry.

Lead-acid batteries discharge from about two point one volts per cell when fully charged to one point seven five volts per cell at complete discharge, translating to twelve point six volts down to ten point five volts for a twelve-volt battery. The voltage varies significantly during discharge, requiring voltage regulation in applications needing stable voltage despite battery state of charge. Automotive electrical systems include voltage regulators maintaining fourteen volts during engine operation to charge batteries and power electrical systems regardless of battery voltage.

End of Life Voltage and When to Replace Batteries

Batteries reach end of useful life not when voltage reaches zero but when voltage drops below levels required for circuit operation. Devices specify minimum operating voltages below which functionality degrades or ceases entirely. A device requiring one point two volts minimum continues operating with partially depleted alkaline batteries maintaining one point three to one point five volts, but stops working when voltage drops below one point two volts even though batteries still contain energy recoverable by devices tolerating lower voltages.

This means batteries “dead” in one device may work in less demanding devices. A battery too depleted to power a digital camera requiring one point three volts might still power a remote control functioning down to zero point nine volts. Transferring partially depleted batteries from high-drain devices to low-drain devices extracts remaining capacity that would otherwise be wasted. Similarly, devices with battery indicators typically warn when voltage approaches minimum operating levels rather than waiting for complete depletion, enabling battery replacement before functionality is lost.

Voltage and Capacity: Understanding Battery Energy Storage

Battery capacity measured in milliamp-hours or amp-hours indicates how much charge the battery stores, while voltage determines the energy represented by that charge, with total energy equal to voltage times capacity.

Capacity Ratings and What They Mean

Battery capacity specified in amp-hours (Ah) or milliamp-hours (mAh) indicates how much total charge the battery can deliver before reaching end of life voltage. A battery rated two thousand milliamp-hours can theoretically deliver two thousand milliamps for one hour, one thousand milliamps for two hours, or five hundred milliamps for four hours before depleting. The actual capacity delivered depends on discharge current, temperature, and end voltage criteria, with high discharge rates reducing usable capacity compared to low discharge rates.

Different battery sizes in the same chemistry have different capacities while maintaining the same voltage because larger physical size allows more active material storing more charge. An AAA alkaline cell and a D alkaline cell both produce one point five volts because they use identical chemistry, but the D cell stores far more capacity—perhaps twelve thousand milliamp-hours versus one thousand milliamp-hours—because its larger volume contains more reactants. This capacity difference explains why D cells last longer than AAA cells in identical applications despite identical voltage.

The capacity rating assumes a specific discharge rate called the rated discharge current, often expressed as a C-rate where C equals the capacity value. A battery with two amp-hour capacity has a 1C discharge rate of two amperes, a 0.1C rate of two hundred milliamps, and a 2C rate of four amperes. Discharging at the rated C-rate typically delivers approximately the rated capacity, while higher C-rates deliver less total capacity because increased voltage drop across internal resistance and electrochemical limitations reduce accessible energy. Low discharge rates often deliver more than rated capacity because more favorable conditions enable extracting additional energy.

Energy Calculation: Watt-Hours

While capacity in amp-hours indicates stored charge, energy in watt-hours more directly indicates useful work the battery can perform because energy accounts for both voltage and capacity. Energy in watt-hours equals voltage times capacity in amp-hours, revealing how both voltage and capacity contribute to total energy storage. A one point five volt battery with two amp-hour capacity stores three watt-hours (one point five times two equals three), while a three point seven volt battery with the same two amp-hour capacity stores seven point four watt-hours—nearly two and a half times more energy despite identical amp-hour capacity.

This voltage-dependent energy storage explains why higher voltage batteries often provide more useful energy from similar physical sizes. A lithium-ion cell with two amp-hour capacity stores about seven point four watt-hours, while four NiMH cells also totaling about two amp-hours store only five point eight watt-hours because the lower one point two volt per cell voltage reduces total energy. For applications where volume and weight matter, lithium chemistries’ higher voltage provides energy density advantages justifying higher cost.

Understanding watt-hour ratings enables comparing batteries with different voltages and capacities on equal terms. Smartphone battery capacities are increasingly specified in watt-hours rather than milliamp-hours because watt-hours directly indicate usable energy regardless of battery voltage, which varies across phone models. A three thousand milliamp-hour battery at three point seven volts stores about eleven watt-hours, comparable to a two thousand eight hundred milliamp-hour battery at four point two volts storing about twelve watt-hours despite lower amp-hour rating.

Series and Parallel Battery Connections

Connecting batteries in series adds their voltages while maintaining capacity. Two one point five volt alkaline cells in series produce three volts at the same capacity as individual cells. Four cells in series produce six volts. This series connection creates higher voltage battery packs from standard cells, enabling voltage matching to circuit requirements without requiring different cell chemistries. However, series connections require matched cells at similar charge states because the total voltage divides across cells proportionally to their resistances, with mismatched cells potentially being over-discharged or overcharged during use.

Parallel battery connections add capacities while maintaining voltage. Two identical batteries in parallel provide the same voltage as one battery but double the capacity and double the maximum current delivery. Parallel connections increase runtime for given loads or enable higher current drains without excessive voltage drop. Battery packs often combine series and parallel connections—multiple parallel groups connected in series—to achieve both desired voltage and capacity. A laptop battery might contain six lithium cells arranged as three parallel pairs in series, providing three times the cell voltage and twice the cell capacity.

Matching Battery Voltage to Circuit Requirements

Selecting appropriate battery voltage for circuits requires understanding circuit voltage requirements, tolerance for voltage variation, and trade-offs between voltage levels affecting circuit design and performance.

Circuit Voltage Requirements and Tolerances

Electronic circuits specify operating voltage ranges within which they function properly, with voltage below the minimum causing malfunction or non-operation and voltage above the maximum potentially damaging components. Simple LED circuits might tolerate wide voltage ranges from three to twelve volts with appropriate current-limiting resistor changes, while sensitive integrated circuits might require voltage within plus or minus five percent of specification for reliable operation.

Understanding these requirements guides battery selection ensuring voltage remains within acceptable ranges throughout battery discharge. A circuit requiring five volts plus or minus five percent needs voltage between four point seven five and five point two five volts. Four alkaline cells in series provide six volts fresh—exceeding the maximum—down to about four point eight volts depleted—approaching the minimum. This voltage range suggests four alkaline cells might not be ideal, with voltage regulation needed to maintain five volts despite battery voltage variation, or alternative battery configurations delivering voltage closer to requirements.

Some circuits include voltage regulators converting battery voltage to regulated voltage independent of battery state of charge, enabling use of batteries whose voltage varies outside circuit tolerance. Linear regulators drop excess voltage, so battery voltage must exceed required circuit voltage by the regulator’s dropout voltage—typically one to three volts. Switching regulators can buck or boost voltage, functioning as voltage increases or decreases, providing more flexibility in battery selection but adding cost and complexity.

Common Voltage Standards and Why They Exist

Common battery voltages reflect standard cell voltages multiplied by practical numbers of series cells. One point five, three, six, nine, and twelve volts for alkaline systems represent two, four, six, and eight cells in series respectively. Three point six to three point seven volts for lithium-ion represents single cells, seven point two to seven point four volts represents two cells, and eleven point one volts represents three cells. These standard voltages simplify battery and device design by enabling common voltage levels across many applications.

Electronic circuits often design around these common voltages to enable use of readily available batteries without requiring custom battery configurations. Devices designed for three volts can use two AA alkaline cells in series, devices requiring nine volts use nine-volt batteries, and devices needing twelve volts use twelve-volt lead-acid or lithium battery packs. This standardization reduces costs through economies of scale and simplifies replacement battery sourcing for consumers.

However, some applications use non-standard voltages selected for specific performance requirements. Electric vehicles might use nominal voltages like forty-eight volts, ninety-six volts, or three hundred volts determined by motor requirements and system power levels rather than standard battery voltages. These applications use series-parallel combinations of standard cells configured to reach desired voltages and capacities.

Higher Voltage Benefits and Trade-offs

Higher voltage systems can deliver the same power at lower current, reducing resistive losses in wiring and enabling more efficient power distribution. This explains why power transmission uses thousands or hundreds of thousands of volts—the enormous reduction in current for given power dramatically reduces resistive heating in transmission lines despite the complexity of high-voltage equipment. For batteries, higher voltage enables thinner lighter wiring for given power levels, important in weight-sensitive applications like drones or portable equipment.

However, higher voltages increase safety concerns through electric shock hazards, require better insulation to prevent arcing or breakdown, and may require protective circuitry preventing over-voltage damage to sensitive components. Low voltage systems like five volts or twelve volts are inherently safer and simpler to implement despite requiring higher currents for equivalent power. The trade-off between voltage level and system complexity influences battery voltage selection based on power requirements, safety concerns, and regulatory requirements.

Practical Battery Selection Considerations

Choosing batteries for projects requires balancing voltage requirements, capacity needs, physical size, cost, availability, and environmental considerations including temperature and discharge rates.

Battery Size and Form Factor

Standard battery sizes including AAA, AA, C, D, and nine-volt provide familiar form factors with specified dimensions and terminals enabling interchangeability across devices. These standardized sizes simplify design by enabling battery holder use and ensuring replacement batteries are widely available. Devices designed for AA batteries can be easily powered by purchasing AA batteries from any store, while custom battery packs might require manufacturer-specific replacements limiting availability and increasing costs.

However, standard sizes constrain available voltage and capacity combinations. AA alkaline cells provide one point five volts at two to three amp-hours regardless of device needs. Applications requiring different voltage or capacity ratios might need multiple cells in series or parallel, or might benefit from custom battery packs optimized for specific requirements. Lithium polymer batteries used in drones and RC vehicles exemplify custom packs configured for specific voltage and capacity matching application needs despite higher cost and custom charger requirements.

Rechargeable Versus Primary Batteries

Primary non-rechargeable batteries cost less initially but must be replaced when depleted, creating ongoing costs and environmental waste. Applications with light power consumption like smoke detectors or remote controls might use primary batteries economically because long life between replacements justifies the lower initial cost and simpler implementation without charging infrastructure.

Rechargeable batteries cost more initially and require chargers adding additional cost and complexity, but can be recharged hundreds or thousands of times before wearing out, dramatically reducing long-term costs and environmental impact in high-use applications. Devices like flashlights, cameras, and portable electronics used frequently benefit from rechargeable batteries despite higher upfront investment. The different voltage of rechargeable NiMH cells—one point two volts versus one point five volts for alkaline—requires consideration when substituting rechargeables for primary cells in devices designed around one point five volt nominal voltage.

Temperature Effects on Battery Voltage and Capacity

Battery performance varies significantly with temperature, with capacity and voltage delivery declining at low temperatures and degradation accelerating at high temperatures. Alkaline batteries lose significant capacity below freezing, with capacity at negative twenty Celsius perhaps half the room temperature capacity. Lithium batteries perform better at low temperatures but still show reduced capacity and increased internal resistance.

High temperatures accelerate chemical degradation and increase self-discharge rates—the gradual capacity loss occurring even when batteries are not used. Storing batteries in hot environments like car interiors reduces shelf life and can create safety hazards particularly with lithium batteries susceptible to thermal runaway at elevated temperatures. Optimal battery storage and operation occurs at room temperature or cooler, with specifications typically assuming twenty to twenty-five Celsius for rated performance.

Conclusion: Voltage as a Fundamental Battery Characteristic

Understanding why batteries have different voltages reveals that voltage is fundamentally determined by electrochemistry, with specific chemical combinations producing characteristic voltages that cannot be altered without changing chemistry. Common battery voltages reflect these electrochemical potentials multiplied by series cell counts, creating standard voltage levels that simplify design and enable widespread availability. The voltage a battery produces, combined with its capacity in amp-hours, determines total energy storage in watt-hours representing actual usable energy the battery provides.

Battery voltage varies during discharge from higher fresh values toward lower end-of-life values, requiring circuit designs that tolerate this variation either through wide operating voltage ranges or through voltage regulation maintaining constant output despite battery state of charge. Understanding discharge curves for different chemistries enables predicting how voltage evolves during use and selecting chemistries whose voltage characteristics match application requirements.

The relationship between voltage, capacity, and energy storage guides battery selection for specific applications, balancing voltage requirements against capacity needs and physical size constraints. Higher voltage batteries enable lower current operation reducing resistive losses and enabling lighter wiring, while lower voltage systems offer simpler implementation and improved safety. Series and parallel battery connections provide flexibility in achieving desired voltage and capacity combinations from standard cells.

Practical battery selection considers voltage requirements alongside capacity needs, physical size, cost, rechargeability, and environmental factors including temperature and discharge rates. Standard battery sizes simplify design and ensure availability despite constraining voltage and capacity options, while custom battery packs enable optimization for specific applications at higher cost. The choice between primary and rechargeable batteries balances initial cost against long-term economics and environmental impact depending on usage patterns.

This understanding of battery voltage enables informed decisions about battery selection, replacement, and circuit design that ensure reliable operation while optimizing cost and performance. Whether selecting batteries for household devices, designing circuits for projects, or troubleshooting voltage-related problems, comprehending why batteries have different voltages and what those voltages mean provides essential knowledge for working effectively with these ubiquitous energy storage devices.